Abstract

Background

Although the protective effect of socioeconomic status (SES) against risk of overweight/obesity is well established, such effects may not be equal across diverse racial and ethnic groups, as suggested by the Marginalization-related Diminished Returns (MDR) theory.

Aims

Built on the MDR theory, this study explored racial variation in the protective effect of income against overweight/obesity of Whites and Blacks with knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods

This cross-sectional study used baseline data of the OA Initiative, a national study of knee OA in the United States. This analysis included 4,664 adults with knee OA, which was composed of 3,790 White and 874 Black individuals. Annual income was the independent variable. Overweight/obesity status (body mass index more than 25 kg/m2) was the dependent variable. Race was the moderator. Logistic regressions were used for data analysis.

Results

Overall, higher income was associated with lower odds of being overweight/obesity. Race and income showed a statistically significant interaction on overweight/obesity status, indicating smaller protective effect of income for Blacks compared to Whites with knee OA. Race-stratified regression models revealed an inverse association between income and overweight/obesity for White but not Black patients.

Conclusions

While higher income protects Whites with knee OA against overweight/obesity, this effect is absent for Blacks with knee OA. Clinicians should not assume that the needs of high-income Whites and Blacks with knee OA are similar, as high-income Blacks may have greater unmet needs than high income Whites. Racially tailored programs may help reduce the health disparities between Whites and Blacks with knee OA. The results are important given that elimination of racial disparities in obesity is a step toward eliminating racial gap in the burden of knee OA. This is particularly important given that overweight/obesity is not only a prognostic factor for OA but also a risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases and premature mortality.

Keywords: ethnic groups, ethnicity, Blacks, African Americans, knee osteoarthritis, obesity, body mass index, socioeconomic status, socioeconomic position, income

1. Introduction

While high socioeconomic status (SES) has a protective effect on health [1–10], this effect is unequal across racial groups [11,12]. Income is among the strongest SES indicators that show protective effects on a wide range of health outcomes [13,14]. Poverty, low income, and financial strain are among well-described risk factors for poor health [15]. Low income also predicts overweight/obesity [16].

The direction and the magnitude of the effects of SES indicators on health [8–10], however, are variant across racial groups [11,12,17]. For example, Black-White differences are shown in the effects of SES indicators such as income and education on overweight/obese status [17]. Differential health effects of SES across racial groups have been attributed to differential access of social groups to the opportunity structure, full access to which is needed to fully take advantage of available resources [18,19]. Although, SES resources such as income reduce population exposure to risk factors and increase their access to buffers [8–10], the real influence of SES indicators in changing life conditions of the populations is different between the minority and the majority groups [20–22]. As a result, diverse racial groups with the very same SES levels would not have similar health, and high SES minorities are in a relative disadvantage than high SES majorities regarding health status [20–22]. Income may differentially impact purchasing power of diverse racial groups [23–26]. Similarly, SES differentially alters a population’s health risk behaviors [8–10,27,28]. For example, education and income have smaller effects on drinking [42], smoking [93], diet [94], self-regulation [95], sleep [121], and suicide [122] for Black individuals than White individuals. This phenomenon is known as Marginalization-related Diminished Returns (MDRs) [11,12,17,39–41]. Extremes of MDRs are when high SES operates as a risk factor for poor mental health of Black men [18,35,43,49,35,50].

Although a considerable body of empirical data supports the MDR theory [11,12], with one exception [122], these studies are all conducted in community rather than clinical settings. While community studies have shown that SES indicators may better protect Whites than Blacks against depression [43], self-rated health [44], chronic disease [43], and mortality [45–48], there is still a need to test these patterns in clinical samples.

Racial disparities in overweight/obesity can be seen in the general population. In the general population, racial disparity in overweight/obese status is among the main contributors to the racial gap in cardio-metabolic morbidity and mortality [51,54,55], as being overweight/obese is one of the main gateways of non-communicable diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease [56,57]. Elimination of racial disparities in overweight/obesity may, thus, reduce the racial gap in cardio-metabolic outcomes [54]. Some of the mechanisms by which racial disparities in overweight/obesity emerge include racial differences in SES [52], environmental conditions [53], and energy-balance behaviors such as diet and exercise [52].

It has been shown that SES alone does not mediate the racial gap in overweight/obesity status [52], as race and SES also have interactive effects on overweight/obese risk. A few studies have suggested that race moderates the effects of SES on overweight/obesity [58,59]. In a cross-sectional study, higher income reduced risk of obesity of White but not Black children [96]. In another longitudinal study, high family SES at birth reduced the risk of obesity of White but not Black youth at age 15 [71]. The literature on racial differences in the SES effects on overweight/obesity, however, are mainly derived from studies on general population.

To better understand the racial differences in the protective effect of income on overweight/obesity in the context of knee osteoarthritis (OA), this study compared Black and White patients with knee OA for the effects of income on overweight/obesity in the United States. The main contribution of this study is to extend the literature from a community to a clinical setting and a specific patient population (i.e. OA).

2. Materials and Methods

Design and setting

This cross-sectional study used data from the baseline status of the OA Initiative, a national study of knee OA in the United States. Data were downloaded from the National Institutes of Health data repository (https://oai.nih.gov) [101].

Sample

The study oversampled Blacks/African Americans. This analysis included 4,664 adults with knee OA, which was composed of 3,790 and 874 White and Black individuals, respectively. Main inclusion criteria were: 1) men and women ages 45 – 79, and 2) All ethnic minorities (oversample African Americans). Major exclusions included 1) Inflammatory arthritis (RA), 2) 3-T MRI contraindication, and 3) Bilateral end-stage knee OA. More detailed justification of the sampling and design of the study is available elsewhere [101].

Measures

This study used data on race, ethnicity, gender, age, and income.

Demographic Characteristics

Gender and age were the demographic variables. Age was a continuous measure, and gender was a dichotomous variable (1 = female, 0 = male).

Annual income

Annual income was the independent variable, which was operationalized in this study as a dichotomous variable with the USD 50,000 being the cut off. This variable was coded as 1 versus 0, with 1 reflecting an annual income of more than USD 50,000. The same cut off is commonly used as a threshold for income [98–100].

Cohorts

The study was composed of three sub-cohorts. 1) Progression cohort determined by symptomatic tibial-femoral knee OA. This group required presence of both osteophytes and frequent symptoms at least in one knee. These included definite tibial-femoral osteophyte (Osteoarthritis Research Society International [OARSI] atlas grade I to III) and presence of pain, ache or stiffness on most days of a month during the past 12 months. 2) Incidence cohort determined by increased risk for symptomatic OA at least in one knee but no symptomatic tibial-femoral OA in either knee. Although x-ray evidence of OA was absent, these patients all had frequent knee symptoms and complaints. They could have osteophytes in either knee, however, should not have frequent symptoms and osteophytes in the same knee. This group required at least two other eligibility risk factors. 3) Control Cohort, determined by lack of symptoms and no radiographic evidence of tibial-femoral or patello-femoral OA in either knee, in addition to absence of any eligibility risk factor.

Overweight/obesity

Overweight/obesity was the dependent variable. Overweight/obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or more, which was calculated based on weight and height directly measured. Overweight/obesity was operationalized as a dichotomized variable composed of under-weight or healthy weight (BMI up to 24.9) versus overweight/obesity (BMI equal to or more than 25.0) which included overweight, as well as class I, class II, and class III of obesity. We considered overweight and obesity with BMI of 25 as a cut off because they both are a risk factor for sores trajectory of OA [97].

Race

Race, the focal moderator, was self-identified as Blacks / African Americans or Whites.

Data Analysis

All data analysis was conducted in Stata 15.0 (Stata Corp.; College Station, TX, USA). As we were only interested in comparison of Whites and Blacks, the analytical sample was composed of Blacks and Whites. To describe the sample, we reported mean (SE) and frequencies (%) overall and by racial group. For multivariable analysis, we used four logistic regression models. In our models, household income was the primary independent variable of interest, overweight/obesity was the primary dependent variable of interest, and age, gender, ethnicity, and cohort were the control variables. Model 1 and Model 2 were estimated in the total sample while Models 3 and 4 were tested in each race. Model 1 did not include our interaction term; however, Model 2 included our interaction term as well (race * household income). Model 3 was specific to Whites and Model 4 was run for Blacks. This analytical strategy was chosen because (a) every modeling strategy of interactions should always start in the absence of interactions, and (b) there is a need to confirm the results of the interaction model with group specific models. In other terms, models should always test additive effects before they test multiplicative effects. As a result, we tested two pooled sample models (Model 1 and Model 2) first. To confirm the result of the Model 2, which suggested a stronger effect in Whites than Blacks, we ran race-specific models. This approach has become the standard way to test racial differences in the very same associations [28,46].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

This analysis included 4,664 adults with knee OA. The sample was composed of 3,790 Whites and 874 Blacks. Table 1 depicts descriptive characteristics of the overall sample, as well as Whites and Blacks with knee OA. As this table shows, Blacks with knee OA were younger, and had lower levels of income but more risk of overweight/obesity than their White counterparts.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for overall sample and by race.

| All | Whites | Blacks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 3,790 | 81.26 | 3,790 | 81.26 | ||

| Black | 874 | 18.74 | 874 | 18.74 | ||

| Gender* | ||||||

| Male | 1,942 | 41.64 | 276 | 31.58 | 1,666 | 43.96 |

| Female | 2,722 | 58.36 | 598 | 68.42 | 2,124 | 56.04 |

| Hispanics | ||||||

| No | 4,634 | 99.40 | 866 | 99.08 | 3,768 | 99.47 |

| Yes | 28 | 0.60 | 8 | 0.92 | 20 | 0.53 |

| Cohort* | ||||||

| Progression Cohort | 1,346 | 28.86 | 372 | 42.56 | 974 | 25.70 |

| Incidence Cohort | 3,198 | 68.57 | 495 | 56.64 | 2,703 | 71.32 |

| Control Cohort | 120 | 2.57 | 7 | 0.80 | 113 | 2.98 |

| High Income* | ||||||

| No | 1,690 | 39.17 | 490 | 63.80 | 1,200 | 33.84 |

| Yes | 2,624 | 60.83 | 278 | 36.20 | 2,346 | 66.16 |

| Overweight/obesity | * | |||||

| No | 1,033 | 22.15 | 75 | 8.58 | 958 | 25.28 |

| Yes | 3,631 | 77.85 | 799 | 91.42 | 2,832 | 74.72 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (Years) * | 62.30 | 0.14 | 62.76 | 0.15 | 60.15 | 0.30 |

Source: Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI), 2004–2006

p < 0.05.

3.2. Pooled Sample Logistic Regressions

Table 2 presents two logistic regressions, one with only the main effects (without interactions) and one with the interaction between race by income. Based on Model 1, overall, high income was associated with lower odds of overweight/obesity in individuals with knee OA. Based on Model 2, race and income showed significant interaction on the odds of overweight/obesity in the individuals with knee OA, which was suggestive of Blacks relative disadvantage compared to Whites regarding the protective effect of high income against overweight/obesity.

Table 2.

Logistic regression parameter estimates (pooled sample).

| OR | SE | p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Main Effects) | ||||

| Race (Blacks) | 2.83 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 2.16 – 3.71 |

| Age (Year) | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.015 | 0.98 – 1.00 |

| Gender (Females) | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.50 – 0.68 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanics) | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.191 | 0.24 – 1.33 |

| Cohort | ||||

| 2 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.42 – 0.61 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.11 – 0.26 |

| Income | 0.76 | 0.07 | 0.002 | 0.65 – 0.90 |

| Intercept | 16.15 | 5.08 | 0.000 | 8.72 – 29.92 |

| Model 2 (Main Effects + Interactions) | ||||

| Race (Blacks) | 2.14 | 0.37 | 0.000 | 1.52 – 3.01 |

| Age (Year) | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.012 | 0.98 – 1.00 |

| Gender (Females) | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.49 – 0.68 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanics) | 0.56 | 0.25 | 0.185 | 0.23 – 1.32 |

| Cohort | ||||

| 2 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.41 – 0.61 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.11 – 0.26 |

| Income | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.000 | 0.60 −0.85 |

| Race (Black) × Income | 2.00 | 0.58 | 0.017 | 1.13 – 3.53 |

| Intercept | 17.48 | 5.53 | 0.000 | 9.40 – 32.51 |

Source: Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI), 2004–2006; Outcome: overweight/obesity, Confidence Interval (CI). The reference cohort is cohort 1 (progression cohort).

3.3. Race Stratified Logistic Regressions

Table 3 describes the results of logistic regression models that were specific to racial groups. Model 3 found a protective effect of high income against odds of overweight/obesity for Whites. Model 4, however, did not show any effect of high income on odds of overweight/obesity for Blacks.

Table 3.

Race-specific logistic regression parameter estimates.

| OR | SE | p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 (Whites) | ||||

| Age (Year) | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.016 | 0.98 – 1.00 |

| Gender (Females) | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.46 – 0.63 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanics) | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.385 | 0.24 – 1.74 |

| Cohort | ||||

| 2 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.42 – 0.63 |

| 3 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.12 – 0.29 |

| Income | 0.70 | 0.06 | 0.000 | 0.59 – 0.84 |

| Intercept | 17.93 | 5.90 | 0.000 | 9.41 – 34.19 |

| Model 4 (Blacks) | ||||

| Age (Year) | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.497 | 0.96 – 1.02 |

| Gender (Females) | 1.27 | 0.35 | 0.385 | 0.74 – 2.17 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanics) | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.156 | 0.05 – 1.59 |

| Cohort | ||||

| 2 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.006 | 0.25 – 0.80 |

| 3 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.01 – 0.30 |

| Income | 1.59 | 0.46 | 0.110 | 0.90 – 2.79 |

| Intercept | 22.70 | 23.25 | 0.002 | 3.05 – 169.01 |

Source: Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI), 2004–2006; Outcome: overweight/obesity, Confidence Interval (CI). The reference cohort is cohort 1 (progression cohort).

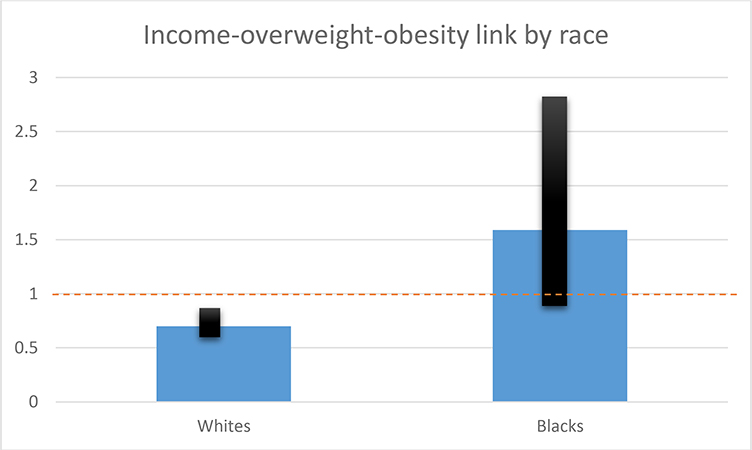

Figure 1 shows that OR of income on overweight/obesity is smaller than 1.00 and the 95% CI does not cross 1.00 for Whites. For Blacks, however, OR of income is larger than 1.00 and 95% CI does include 1.00.

Figure 1.

Odds ratio estimates on the association of income and overweight/obesity by race in patients with knee osteoarthritis. For White patients, the OR is smaller than 1.00 and 95% CI does not include 1 (protective). For Black patients, however, the OR is larger than 1.00 and 95% CI does include 1 (non-protective). The 95% confidence intervals are shown in black. Estimates are from models 3 and 4 in Table 3 with all variables set at their mean.”

4. Discussion

The study documented considerable racial differences in the association between income and overweight/obesity in patients with knee OA. Among individuals with knee OA, risk of overweight/obesity depends on income level for White but not Black patients. That means, Blacks with OA remain at high risk of overweight/obesity across all income levels.

Our first finding (the protective effect of income against being overweight/obese in the pooled sample and among Whites with knee OA) supports previous studies on how SES resources reduce undesired health outcomes including overweight/obesity [71,84–89]. High SES has shown strong effects on many physical and mental health outcomes [1–3].

The very same income, however, shows a stronger protective effect against overweight/obesity for privileged individuals than marginalized individuals with knee OA. This is the first time such a finding is reported for a clinical sample. With one study being the exception [122], all other previous findings on MDRs have enrolled participants from the general population.

These findings can be better understood in the context of three recent studies [71]. The first study documented Black–White differences in the protective effect of family SES at birth on subsequent BMI of youth at age 15. Similar to this work, the previously mentioned study showed that family SES has an interaction on BMI, indicating smaller gains of high SES in terms of low BMI for Blacks compared to Whites [71]. The second study showed that high income protects Whites but not Black children against obesity [96]. In the third study, while high SES was linked to low prevalence of overweight/obesity, this association could be only found for Whites but not for Blacks [72].

In the United States, given the existing racial residential segregation, race is a close proxy of living conditions, access to resources, and opportunities [79]. As a result of residential segregation, the very same income gives different purchasing power to various racial groups [80]. Density of fast food restaurants is higher in predominantly Black neighborhoods. Blacks are more likely than Whites to reside in food deserts that have low availability of fresh healthy food options [81–83]. As this study did not focus on neighborhood factors, future research may focus on multi-level determinants of diminished return of income on diet and exercise of Blacks compared to Whites.

Social determinants of health may have less than expected effects on the health of racial minority groups, as shown here for prevalence of overweight/obesity among patients with knee OA. Diminished returns of SES are shown for children [11,12], adults [28], and older adults [17]. It is not just educational attainment [122] and income [17,46], but also employment [90] and marital status [97] that generate poorer health outcomes for Blacks than for Whites. These patterns are indicative of a systemic MDR for non-Whites [17,44,46,92].

The results should be interpreted with some caution. We do not argue that because Blacks do not necessarily benefit from high SES, they should therefore not be inclined to enhance their SES. Such racist argumentation would assume that racial differences are innate. However, race is a social, political, and economic construct [107–1133], and racial differences are the result of socialization, racism, and discrimination. We argue that the solution to racial disparities is beyond SES and should also address Blacks’ ability to translate their SES resources such as income to tangible outcomes. One example policy would be enhancing walkability of inner cities and urban areas, enhancing safety, and reducing crime, and increasing healthy food outlets in inner cities. It will be under such conditions that income would similarly result in health for Whites and Blacks.

The diminished returns of SES (MDRs) are likely to be due to fundamental and structural causes that are closely linked to race as a social and political construct [107,108]. Differential distribution of political power, differential distribution of wealth, underrepresentation of Blacks in the US political system, residential segregation, and racism across institutions are all higher-level factors that may contribute to the existing MDRs [107–113].

We argue that slavery, Jim Crow, social stratification, and marginalization are responsible for the MDRs. Such structural factors may not allow Black people to fully enjoy income returns on their health. A history of slavery, Jim Crow, and the existing racism are all powerful determinants of differential distribution of stress in the daily lives of sub-populations, particularly those defined by race and color. The roles of law, history, and politics on shaping residential segregation, racial income inequality, and racism are known [108]. Still, a large section of the US population, and some political parties deny that racism and discrimination exist in today US. While the existing racism is being ignored by some sections of the US society, systemic MDRs reflect the systemic racism in the U.S. society [116–120].

MDRs is seen across settings, age groups, contexts, and outcomes. The systemic nature of MDRs invites federal and governmental interventions. Although the US government may theoretically get involved to reduce racism, such action may also result in a backlash by other sections of the US society. Governmental interventions in the US have serious opponents, thus governmental solutions to reduce racism remains controversial.

Previous work has proposed some policies and programs that may reduce these types of problems. We know that poverty alleviation, improvement of the built environment, and reduction of residential segregation should be a part of the solution. The problem is not what is the solution but is how to gain bipartisan political support for such actions [111–113]. Some political parties are against implementation of radical social policy solutions. Some political parties with access to power have invested in maintaining the status quo [112]. As a result, progress—in matters of life and death—is painfully slow [111–113]. We argue that to better understand which economic policies can be most effective, the contribution of the US political context on health disparities should be understood and discussed [111–113]. This study goes beyond a successful replication of previous studies and invites researchers to discuss policy solutions that can minimize MDRs, given the unique aspects of the US political environment. Future research should test the interplay between race, racism, class, political environment, social structure, and health [102–106].

Implications

This result may have some clinical implications for practice as well as research on diverse populations with knee OA. Clinicians should recognize that the health statuses of high SES individuals who are from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds differ. The diminished returns of SES in Blacks with knee OA should not be ignored as it suggests high SES Blacks with knee OA may have greater health needs than their White counterparts. There is a need to develop strategies for prevention and treatment of obesity particularly for Blacks with knee OA. There is a need to develop culturally sensitive programs that consider Black individuals’ specific needs and beliefs. There may be a particular need for enhancing exercise and improving the diets of Blacks with knee OA. There is a need for programs helping to reduce health disparities. More specifically, according to estimates, racially tailored programs need to compensate for the diminishing returns of existing resources among Blacks. Such strategies may thereby ameliorate overweight/obesity—which complicates knee OA particularly in Black patients. We argue that MDRs should be undone by programs such as case management or patient navigation, that help individuals use their available resources. We argue that MDRs are indicative that highly educated Blacks with OA require more intensive attention than highly educated White patients with OA. Future research, however, should test various ways by which we can design tailored interventions in which African American patients with OA can receive more intensive healthcare utilization.

The results are also relevant to the policy level, as obesity is not just a function of individual behavior but also contextual factors such as walkability and availability of food in neighborhoods and communities. High availability of fast food and energy dense diets may have a role in the highly segregated residential areas that do not easily provide healthy food for racial and minority groups. Such policy levels may be an important element of elimination of the racial gap in overweight/obesity.

5. Limitations

The main contribution of this study is that it extends an existing literature on MDRs from the general population to a clinical sample of patients with knee OA. Thus, although some similar results were already available from other research, none of the previous work was conducted in clinical samples and none was performed on patients with knee OA. As testing MDRs was not the primary intent behind the data collected, we were limited to the variables that we could apply. In addition, there was a limited sample of African Americans participating as compared to Whites. These issues limit the results of the current study.

The first methodological limitation of this study is a cross-sectional design which limits any causal inferences. While it is more likely that low income results in overweight/obesity, obesity may also interfere with work, and may result in a decline in SES. There is a need to replicate the findings reported here using longitudinal design. Second, the current analysis only studied income. Other SES indicators should be studied and include family structure, education, occupation, employment, and wealth. Third, few clinical variables were included in this study. Fourth, all of the study measures were at the individual level and were related to the patient. However, contextual factors such as neighborhood and family that the individuals are embedded in have a role. Fifth, we only focused on differences between Blacks and Whites, and there is a need to replicate the findings of this study using other socially and economically marginalized groups such as Indian Americans and Hispanics. Sixth, income was a dichotomous variable, and exact income was not known. Seventh, we did not model BMI but categorical overweight/obesity. In addition, this study did not include cultural or behavioral measures and mechanisms such as diet, eating habits, density of fast food restaurants that could differ for high income Whites and Blacks. We do not know how representative the sample of this study is in terms of knee OA as well as with respect to the general African American population in the US. The study is also limited to the period over which patients were participating, as the effect that earlier experiences including nutrition, occupational status and job requirements as well as SES (which may not be fluid over the course of a lifetime) cannot be accounted for. Despite these potential limitations, the current study was one of the very few investigations that have documented minorities’ diminished returns as a contributing factor for the racial gap in overweight/obesity in knee OA.

6. Conclusions

Racial groups do not similarly gain health from their income, and this is also relevant to the epidemiology and burden of overweight/obesity in individuals with knee OA. Due to differential treatment by the society, lower purchasing power, residential segregation, differential access to fast foods, or individual behaviors, the burden of overweight/obesity is not equal for high-income White and Black individuals with knee OA. This finding is in line with what we know regarding minorities’ diminished returns of SES. High SES Blacks with knee OA may have higher health needs than their White counterparts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mohammed Saqib, University of Michigan, for his contribution to the draft of this paper.

Funding: SA and MB are supported by the NIH awards 54MD008149 and # R25 MD007610, U54MD007598, and U54 TR001627. SA is also supported by the NIH grant 5S21MD000103.

Ethical approval

The Michigan State University (MSU) Institutional Review Board (IRB) exempted the SOSS study protocol from ethical review (IRB Approval code = x95-499e). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participants received a financial incentive for their participation. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (include name of committee + reference number) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Mirowsky J; Ross CE Education, Social Status, and Health; Aldine de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen ME; González HM Childhood socioeconomic position and disability in later life: Results of the health and retirement study. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S197–S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herd P; Goesling B; House JS Socioeconomic position and health: The differential effects of education versus income on the onset versus progression of health problems. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 223–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leopold L; Engelhardt H Education and physical health trajectories in old age. Evidence from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davey S; Hart C; Hole D; MacKinnon P; Gillis C; Watt G; Blane D Hawthorne V. Education and occupational social class: Which is the more important indicator of mortality risk? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conti G; Heckman J; Urzua S The education-health gradient. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 234–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker DP; Leon J; Smith Greenaway EG; Collins J; Movit M The education effect on population health: A reassessment. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2011, 37, 307–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phelan JC; Link BG; Tehranifar P Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S28–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Link BG; Phelan J Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities In Handbook of Medical Sociology, 6th ed; Bird CE, Conrad P, Fremont AM, Timmermans S Eds.; Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 2010, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link B; Phelan J Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assari S Unequal gain of equal resources across racial groups. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Assari S Health Disparities due to Diminished Return among Black Americans: Public Policy Solutions. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2018, 12, 112–145, doi: 10.1111/sipr.12042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alaimo K; Olson CM; Frongillo EA Jr.; Briefel RR Food insufficiency, family income, and health in US preschool and school-aged children. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah CP; Kahan M; Krauser J The health of children of low-income families. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1987, 137, 485–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen E Why socioeconomic status affects the health of children: A psychosocial perspective. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 13, 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baughcum AE; Burklow KA; Deeks CM; Powers SW; Whitaker RC Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity: A focus group study of low-income mothers. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1998, 152, 1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham TJ, Seeman TE, Kawachi I, Gortmaker SL, Jacobs DR, Kiefe CI, Berkman LF. Racial/ethnic and gender differences in the association between self-reported experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and inflammation in the CARDIA cohort of 4 US communities. Soc Sci Med 2012. September;75(5):922–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson DL; Bullard KM; Neighbors HW; Geronimus AT; Yang J; Jackson JS Are benefits conferred with greater socioeconomic position undermined by racial discrimination among African American men? J. Men Health 2012, 9, 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson DL Race, Socioeconomic Position and Depression: The Mental Health Costs of Upward Mobility. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keil JE; Sutherland SE; Knapp RG; Tyroler HA Does equal socioeconomic status in black and white men mean equal risk of mortality? Am. J. Public Health 1992, 82, 1133–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller-Rowell TE; Doan SN The social costs of academic success across ethnic groups. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 1696–1713, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuller-Rowell TE; Curtis DS; Doan SN; Coe CL Racial disparities in the health benefits of educational attainment: A study of inflammatory trajectories among African American and white adults. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 33–40, doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper RS Health and the social status of blacks in the United States. Ann. Epidemiol. 1993, 3,137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams DR; Collins C Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001, 116, 404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams DR; Yu Y; Jackson JS; Anderson NB Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams DR; Neighbors HW; Jackson JS Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunello G; Fort M; Schneeweis N; Winter-Ebmer R The causal effect of education on health: What is the role of health behaviors? Health Econ. 2016, 25, 314–336, doi: 10.1002/hec.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assari S; Lankarani MM Education and Alcohol Consumption among Older Americans; Black-White Differences. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 67, doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juhn YJ; Beebe TJ; Finnie DM; Sloan J; Wheeler PH; Yawn B; Williams AR Development and initial testing of a new socioeconomic status measure based on housing data. J. Urban Health 2011, 88, 933–944, doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross CE; Wu CL The links between education and health. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1995, 60, 719–745. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu SY; Chavan NR; Glymour MM Type of high-school credentials and older age ADL and IADL limitations: Is the GED credential equivalent to a diploma? Gerontologist 2013, 53, 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zajacova A; Everett BG The nonequivalent health of high school equivalents. Soc. Sci. Q. 2014, 95, 221–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds JR; Ross CE Social stratification and health: Education’s benefit beyond economic status and social origins. Soc. Probl. 1998, 45, 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoddard P; Adler NE Education associations with smoking and leisure-time physical inactivity among Hispanic and Asian young adults. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudson DL; Neighbors HW; Geronimus AT; Jackson JS The relationship between socioeconomic position and depression among a US nationally representative sample of African Americans. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 373–381, doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0348-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyson K; Darity W Jr.; Castellino DR It’s not “a black thing”: Understanding the burden of acting white and other dilemmas of high achievement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 582–605. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neighbors HW; Njai R; Jackson JS Race, ethnicity, John Henryism, and depressive symptoms: The national survey of American life adult reinterview. Res. Hum. Dev. 2007, 4, 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montez JK; Hummer RA; Hayward MD Educational attainment and adult mortality in the United States: A systematic analysis of functional form. Demography 2012, 49, 315–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marmot M; Allen JJ Social determinants of health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, S517–S519, doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross CE; Mirowsky J Refining the association between education and health: The effects of quantity, credential, and selectivity. Demography 1999, 36, 445–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montez JK; Hummer RA; Hayward MD; Woo H; Rogers RG Trends in the educational gradient of US adult mortality from 1986 through 2006 by race, gender, and age group. Res. Aging 2011, 33, 145–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hummer RA; Lariscy JT Educational attainment and adult mortality In International Handbook of Adult Mortality; Rogers RG, Crimmins EM, Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands: 2011; pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Assari S Combined Racial and Gender Differences in the Long-Term Predictive Role of Education on Depressive Symptoms and Chronic Medical Conditions. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2016, doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farmer MM, Ferraro KF. Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status? Soc Sci Med. 2005. January;60(1):191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayward MD; Hummer RA; Sasson I Trends and group differences in the association between educational attainment and U.S. adult mortality: Implications for understanding education’s causal influence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 127, 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Assari S; Lankarani MM Race and Urbanity Alter the Protective Effect of Education but not Income on Mortality. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 100, doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Backlund E; Sorlie PD; Johnson NJ A comparison of the relationships of education and income with mortality: The National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 1373–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Everett BG; Rehkopf DH; Rogers RG The Nonlinear Relationship between Education and Mortality: An Examination of Cohort, Race/Ethnic, and Gender Differences. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2013, 1, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Assari S, Caldwell CH. High Risk of Depression in High-Income African American Boys. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Social Determinants of Depression: The Intersections of Race, Gender, and Socioeconomic Status. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, pii: E156, doi: 10.3390/brainsci7120156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fontaine KR; Redden DT; Wang C; Westfall AO; Allison DB Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA 2003, 289, 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qobadi M; Payton M Racial Disparities in Obesity Prevalence in Mississippi: Role of Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, pii: E258, doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singleton CR; Affuso O; Sen B Decomposing Racial Disparities in Obesity Prevalence: Variations in Retail Food Environment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 365–372, doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson D; Edelsberg J; Colditz GA; Bird AP; Oster G Lifetime health and economic consequences of obesity. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 2177–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daw J Contribution of Four Comorbid Conditions to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Mortality Risk. Am. J. Prev. Med 2017, 52, S95–S102, doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frühbeck G; Yumuk V Obesity: A gateway disease with a rising prevalence. Obes. Facts. 2014, 2, 33–36, doi: 10.1159/000361004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frühbeck G; Toplak H; Woodward E; Yumuk V; Maislos M; Oppert JM Executive Committee of the European Association for the Study of Obesity. Obesity: The gateway to ill health—An EASO position statement on a rising public health, clinical and scientific challenge in Europe. Obes. Facts 2013, 6, 117–120, doi: 10.1159/000350627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bleich SN; Thorpe RJ Jr.; Sharif-Harris H; Fesahazion R; Laveist TA Social context explains race disparities in obesity among women. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2010, 64, 465–469, doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.096297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krueger PM; Reither EN Mind the gap: Race/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in obesity. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015, 15, 95, doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0666-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blumberg SJ; Foster EB; Frasier AM; Satorius J; Skalland BJ; Nysse-Carris KL; Morrison HM; Chowdhury SR; O’Connor KS Design and operation of the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2007. Vital Health Stat. 1 2012, 55, 1–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Dyck P1; Kogan MD; Heppel D; Blumberg SJ; Cynamon ML; Newacheck PW The National Survey of Children’s Health: A new data resource. Matern. Child Health J. 2004, 8, 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bramlett MD; Blumberg SJ Family structure and children’s physical and mental health. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Assari S Education Attainment Better Helps White than Black Parents to Escape Poverty; National Survey of Children’s Health. Economies 2018, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spencer EA; Appleby PN; Davey GK; Key TJ Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 561–565, doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stewart AL The reliability and validity of self-reported weight and height. J. Chronic Dis. 1982, 35, 295–309, doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stommel M; Schoenborn CA Accuracy and usefulness of BMI measures based on self-reported weight and height: Findings from the NHANES & NHIS 2001–2006. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 421, doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pursey K; Burrows TL; Stanwell P; Collins CE How accurate is web-based self-reported height, weight, and body mass index in young adults? J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e4, doi: 10.2196/jmir.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Powell-Young YM The validity of self-report weight and height as a surrogate method for direct measurement. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2012, 25, 25–30, doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hicken MT, Lee H, Mezuk B, Kershaw KN, Rafferty J, Jackson JS. Racial and ethnic differences in the association between obesity and depression in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013. May;22(5):445–52. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.National Survey of Children’s Health CATI Instrument. Available online: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/health_statistics/nchs/slaits/nsch07/1a_Survey_Instrument_English/NSCH_Questionnaire_052109.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- 71.Assari S; Thomas A; Caldwell CH; Mincy RB Blacks’ Diminished Health Return of Family Structure and Socioeconomic Status; 15 Years of Follow-up of a National Urban Sample of Youth. J. Urban Health 2018, doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0217-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fradkin C; Wallander JL; Elliott MN; Tortolero S; Cuccaro P; Schuster MA Associations between socioeconomic status and obesity in diverse, young adolescents: Variation across race/ethnicity and gender. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 1–9, doi: 10.1037/hea0000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adler NE; Stewart J Reducing obesity: Motivating action while not blaming the victim. Milbank Q. 2009, 87, 49–70, doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gee GC; Ford CL Structural racism and health inequities: Old Issues, New Directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011, 8, 115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bailey ZD; Krieger N; Agénor M; Graves J; Linos N; Bassett MT Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams DR; Mohammed SA Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, doi: 10.1177/0002764213487340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Assari S; Lankarani MM The Association Between Obesity and Weight Loss Intention Weaker Among Blacks and Men than Whites and Women. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2015, 2, 414–420, doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0115-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chithambo TP, Huey SJ. Black/white differences in perceived weight and attractiveness among overweight women. J Obes. 2013;2013:320326. doi: 10.1155/2013/320326. Epub 2013 Feb 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sudano JJ; Perzynski A; Wong DW; Colabianchi N; Litaker D Neighborhood racial residential segregation and changes in health or death among older adults. Health Place 2013, 19, 80–88, doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zenk SN; Schulz AJ; Israel BA; James SA; Bao S; Wilson ML Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 660–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kwate NO Fried chicken and fresh apples: Racial segregation as a fundamental cause of fast food density in black neighborhoods. Health Place 2008, 14, 32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bower KM; Thorpe RJ Jr.; Rohde C; Gaskin DJ The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States. Prev. Med. 2014, 58, 33–39, doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bower KM; Thorpe RJ Jr.; Yenokyan G; McGinty EE; Dubay L; Gaskin DJ Racial Residential Segregation and Disparities in Obesity among Women. J. Urban Health 2015, 92, 843–852, doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9974-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sobal J; Stunkard AJ Socioeconomic status and obesity: A review of the literature. Psychol. Bull. 1989, 105, 260–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McLaren L Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol. Rev. 2007, 29, 29–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ben-Shlomo Y; Kuh D A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuh D; Ben-Shlomo Y; Lynch J; Hallqvist J; Power C Life course epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health the added effects of racism and discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999. December 1;896(1):173–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ogden CL; Lamb MM; Carroll MD; Flegal KM Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States 1988–1994 and 2005–2008. NCHS data brief no 50. National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Assari S Life Expectancy Gain Due to Employment Status Depends on Race, Gender, Education, and Their Intersections. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0381-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zissimopoulos JM, Barthold D, Brinton RD, Joyce G. Sex and Race Differences in the Association Between Statin Use and the Incidence of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017. February 1;74(2):225–232. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bensley KM, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, Gordon AJ, Kraemer KL, Bryant KJ, Edelman EJ, Crystal S, Gaither JR, Korthuis PT, Marshall BDL, Ornelas IJ, Chan KCG, Dombrowski JC, Fortney JC, Justice AC, Williams EC. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between alcohol use and mortality among men living with HIV. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2018. January 22;13(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13722-017-0103-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Assari S; Mistry R Educational Attainment and Smoking Status in a National Sample of American Adults; Evidence for the Blacks’ Diminished Return. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Assari S; Lankarani MM Educational Attainment Promotes Fruit and Vegetable Intake for Whites but Not Blacks. J 2018, 1, 29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Assari S; Caldwell CH; Mincy R Family Socioeconomic Status at Birth and Youth Impulsivity at Age 15; Blacks’ Diminished Return. Children 2018, 5, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Assari S Family Income Reduces Risk of Obesity for White but Not Black Children. Children 2018, 5, 73 Assari, S.; Caldwell, C.H.; Zimmerman, M.A. Family Structure and Subsequent Anxiety Symptoms; Minorities’ Diminished Return. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. Jama. 1999. October 27;282(16):1523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Downey L, Hawkins B. RACE, INCOME, AND ENVIRONMENTAL INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES. Sociol Perspect. 2008. December 1;51(4):759–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Unger JM, Gralow JR, Albain KS, Ramsey SD, Hershman DL. Patient Income Level and Cancer Clinical Trial Participation: A Prospective Survey Study. JAMA Oncol. 2016. January;2(1):137–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cardet JC, Louisias M, King TS, Castro M, Codispoti CD, Dunn R, Engle L, Giles BL, Holguin F, Lima JJ, Long D, Lugogo N, Nyenhuis S, Ortega VE, Ramratnam S, Wechsler ME, Israel E, Phipatanakul W; Vitamin D Add-On Therapy Enhances Corticosteroid Disparities Working Group members on behalf of the AsthmaNet investigators. Income is an independent risk factor for worse asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018. February;141(2):754–760.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Peterfy CG, Schneider E, Nevitt M. The osteoarthritis initiative: report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008. December;16(12):1433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Rodriguez JM, Timpe B. Weathering, Drugs, and Whack-a-Mole: Fundamental and Proximate Causes of Widening Educational Inequity in U.S. Life Expectancy by Sex and Race, 1990–2015. J Health Soc Behav. 2019. June;60(2):222–239. doi: 10.1177/0022146519849932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bound J, Geronimus AT, Rodriguez JM, Waidmann TA. Measuring Recent Apparent Declines In Longevity: The Role Of Increasing Educational Attainment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015. Dec;34(12):2167–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wilson KB, Thorpe RJ Jr, LaVeist TA. Dollar for Dollar: Racial and ethnic inequalities in health and health-related outcomes among persons with very high income. Prev Med. 2017. March;96:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Seamans MJ, Robinson WR, Thorpe RJ Jr, Cole SR, LaVeist TA. Exploring racial differences in the obesity gender gap. Ann Epidemiol. 2015. June;25(6):420–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Navarro V What we mean by social determinants of health. Glob Health Promot. 2009. March;16(1):5–16. doi: 10.1177/1757975908100746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rodriguez JM. The politics hypothesis and racial disparities in infants’ health in the United States. SSM-Population Health. 2019. July 6:100440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rodriguez JM, Karlamangla AS, Gruenewald TL, Miller-Martinez D, Merkin SS, Seeman TE. Social stratification and allostatic load: shapes of health differences in the MIDUS study in the United States. Journal of biosocial science. 2019. January 28:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rodriguez JM, Geronimus AT, Bound J, Dorling D. Black lives matter: Differential mortality and the racial composition of the US electorate, 1970–2004. Social Science & Medicine. 2015. July 1;136:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rodriguez JM, Karlamangla AS, Gruenewald TL, Miller-Martinez D, Merkin SS, Seeman TE. Social stratification and allostatic load: shapes of health differences in the MIDUS study in the United States. Journal of biosocial science. 2019. January 28:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rodriguez JM, Bound J, Geronimus AT. US infant mortality and the President’s party. International journal of epidemiology. 2013. December 31;43(3):818–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rodriguez JM. Health disparities, politics, and the maintenance of the status quo: A new theory of inequality. Social Science & Medicine. 2018. March 1;200:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rodriguez JM. Health disparities, politics, and the maintenance of the status quo: A new theory of inequality. Social Science & Medicine. 2018. March 1;200:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Valentino NA, Sears DO. Old times there are not forgotten: Race and partisan realignment in the contemporary South. American Journal of Political Science. 2005. July;49(3):672–88. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tesler M, Sears DO. Obama’s race: The 2008 election and the dream of a post-racial America. University of Chicago Press; 2010. November 15. [Google Scholar]

- 116.LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, editors. Race, ethnicity, and health: A public health reader. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. October 16. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Metzl JM. Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland. Hachette UK; 2019. Mar 5. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Navarro V The politics of health policy: The US reforms, 1980–1994. Oxford: Blackwell; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 119.LaVeist TA. The political empowerment and health status of African-Americans: mapping a new territory. American Journal of Sociology. 1992. January 1;97(4):1080–95. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010. February;1186:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Assari S, Nikahd A, Malekahmadi MR, Lankarani MM, Zamanian H. Race by gender group differences in the protective effects of socioeconomic factors against sustained health problems across five domains. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0291-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Assari S, Schatten HT, Arias SA, Miller IW, Camargo CA, Boudreaux ED. Higher educational attainment is associated with lower risk of a future suicide attempt among non-Hispanic Whites but not non-Hispanic Blacks. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2019. July 5:1–0. Doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00601-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]