Abstract

An important aspect of cellular function is the correct targeting and delivery of newly synthesized proteins. Central to this task is the machinery of the Sec translocon, a transmembrane channel that is involved in both the translocation of nascent proteins across cell membranes and the integration of proteins into the membrane. Considerable experimental and computational effort has focused on the Sec translocon and its role in nascent protein biosynthesis, including the correct folding and expression of integral membrane proteins. However, the use of molecular simulation methods to explore Sec-facilitated protein biosynthesis is hindered by the large system sizes and long (i.e., minute) timescales involved. In this work, we describe the development and application of a coarse-grained simulation approach that addresses these challenges and allows for direct comparison with both in vivo and in vitro experiments. The method reproduces a wide range of experimental observations, providing new insights into the underlying molecular mechanisms, predictions for new experiments, and a strategy for the rational enhancement of membrane protein expression levels.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The Sec translocon is a multi-protein complex that plays a central role in the production of new membrane proteins and secretory proteins in the cell.1–4 Integration into the cell membrane via the Sec translocon is a crucial step in membrane protein folding and can be a bottleneck in the production of membrane proteins.5 Translocation across the cell membrane via the Sec translocon is required for the export of many secretory proteins, as well as for the passage of the extracytoplasmic domains of membrane proteins. Most integral membrane proteins (IMPs) and many secretory proteins are translated at the translocon, with the ribosome (Fig. 1A, orange) docked onto the cytosolic side of the Sec translocon. The nascent polypeptide chain (NC) is inserted into the central pore of the translocon (Fig. 1, pink), Sec61 in the eukaryotic ER membrane or SecYEG in bacteria. Extracytoplasmic loops and secretory proteins utilize the central pore as a passageway across the hydrophobic lipid membrane, while the hydrophobic domains of IMPs insert into the lipid membrane via a lateral gate (LG) (Fig. 1, green).6,7

Figure 1:

Structural representation of the ribosome-translocon complex from (A) cryoEM (PDB ID: 3J7R)8 (B) and CGMD.9 The ribosome(orange), shown cropped, is docked at the cytosolic opening of the Sec translocon (pink). The lateral gate (LG) helices of the translocon (green) can separate to create a lateral opening into the ER membrane (grey region) through which transmembrane domains can partition into the lipid membrane.

The Sec translocon has been extensively studied due to its important role in the early stages of membrane protein folding and the secretion of secretory proteins. Significant progress has been made in elucidating the mechanisms of targeting to the translocon and post-translational translocation,10,11 however in this perspective we will focus processes for which the translating ribosome is docked onto the translocon. Such co-translational processes determine which proteins will integrate into the membrane, as well as which topology (i.e., orientation with respect to the lipid membrane) the membrane proteins adopt. Previous experimental work has demonstrated that these different outcomes are encoded in the primary sequence of the nascent chain. Hydrophobicity in particular can induce opening of the Sec LG and lead to integration into the membrane.12–20 Charges in the loops also impact topology formation, as reflected in the ‘positive-inside rule’, as well as leading to more nuanced effects.21,22 Sequence-based metrics cannot tell the whole story, however, since topology formation is not purely driven by thermodynamics, but can also be kinetically controlled; this is strikingly highlighted by experiments that show the topology of an IMP to be affected by changes in the rate of NC translation in the absence of changes to the primary sequence.23

Computational simulation is a powerful tool to accurately capture the interplay between thermodynamics and kinetics during protein biosynthesis. Considerable effort has been dedicated to the computational modeling of both co-translational protein biosynthesis and folding, both in the presence9,24–28 and absence26,29 of the Sec translocon. The slow timescales of ribosomal translation (approximately 5–20 amino-acids per second) vastly exceed those of typical biomolecular simulations, creating the need for coarse-grained modeling strategies. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CGMD) provides a flexible tool for exploring the effects of competing timescales and molecular interactions, as well as serving as a unifying framework for understanding a range of different experimental assays. In this Perspective, we survey the field of CGMD modeling strategies for co-translational protein biosynthesis, before focusing on a specific CGMD model9,28 for processes that are facilitated by the Sec translocon (Fig. 1B). We discuss the foundations of this CGMD model, its validation against quantitative experimental results, and its scope for new predictions.

Coarse-graining for protein biosynthesis

At a fundamental level, computational modeling of protein biosynthesis faces a demanding interplay between feasibility and accuracy. Protein biosynthesis introduces extraordinary demands in terms of computational costs. In addition to the slow (minute-timescale) dynamics of protein translation for a single CGMD trajectory, simulations of this length must be performed thousands of times for a given NC sequence to obtain statistically significant averaging, and this full ensemble of trajectories must be performed for each NC sequence of interest (i.e, each possible mutation). Given that the state of the art for atomistic simulation is to perform individual milli-microsecond trajectories of a single protein sequence, it is clear that coarse-graining is necessary.

For soluble proteins that undergo biosynthesis without the Sec translocon, a variety of successful coarse-grained models have been developed.26 These coarse-grained models allow investigation of unique features of co-translational protein folding, such as; interactions with the ribosome, the sequential addition of NC amino-acids, and the effect of variability in translation rates. In particular, simulations using coarse-grained models reveal how the local confinement,30–32 and specific interactions between the NC and the ribosome33,34 can affect NC folding, and lead to different outcomes than folding in bulk solvent. For example, O’Brien and coworkers used a combination of coarse-grained simulation and experiment to show that formation of tertiary structure can already take place within the ribosomal exit tunnel.35 The translated NC emerges from the ribosome sequentially, a situation that significantly differs from re-folding in bulk solution. Shakhnovich and coworkers used a lattice model for protein folding to show how NC growth during folding can affect folding kinetics by speeding up folding for NCs with mostly local contacts; the effects can also lead to a different final folded state by favoring local NC-NC interactions over distant interactions.36 Elcock and coworkers use an off-lattice model with a realistic ribosome geometry to compare co-translational folding to folding in bulk for three distinct proteins. While the kinetics of co-translational folding and refolding in bulk was found to be similar for the small globular proteins Barnase and Chymotrypsin inhibitor, a two-domain protease, Semliki forest virus protein, was found to fold via a distinct pathway co-translationally.29 Further coarse-grained simulation studies show additional examples of proteins for which co-translational folding pathways are meaningfully different37,38 or similar39 to folding in bulk. A related aspect of co-translational folding which can be captured through coarse-grained modelling is the dependence of folding pathways on translation rate. Translating ribosomes typically add amino-acids to the NC at a codon-dependent rate of 2–20 residues per second. O’Brien and coworkers have also used kinetic modeling to show how translation rate control can promote protein folding; an increased rate of translation can avoid local misfolding, while a decreased rate of translation can facilitate local structure formation.40 These studies demonstrate that coarse-grained modeling can successfully describe co-translational folding of soluble proteins on biological timescales. However, simulation of the biosynthesis of secretory and integral membrane proteins via the Sec pathway presents unique challenges.

For secretory and integral membrane proteins that are biosynthesized via the Sec pathway, less coarse-grained modeling work has been performed.9,28,41 For the modeling of this pathway, a pioneering study by Samson and coworkers used a combination of all-atom classical molecular dynamic (MD) simulations and elastic network models to explore the dynamics of the Sec translocon, revealing the principle motions that allow channel gating to the lipid membrane.42 Further MD simulations have investigated the energetics of translocation across the membrane24 and integration into the membrane7,27,43,44 for model NC segments. Despite providing valuable insights into the energetics of co-translational integration and translocation, these fine-resolution models are not suitable for the long timescales of co-translational biosynthesis. To this end, Warshel and coworkers have developed a two-dimensional coarse-grained model that can simulate the passage of a model NC sequence from the ribosome into the Sec translocon,41 which was used to explore the forces exerted on the NC by the translocon and the ribosome during translation, although the model does not explicitly include the conformational dynamics of the Sec translocon. The current Perspective focuses on a CGMD model that allows for direct simulation of co-translational protein biosynethesis via the Sec pathway while explicitly including the conformational dynamics of the translocon.

A coarse-grained model for Sec-facilitated protein biosynthesis

Co-translational membrane integration and translocation of NCs via the Sec translocon involves a hierarchy of coupled timescales, ranging from nanoseconds (i.e., structural fluctuations) to milliseconds (i.e., translocon conformational gating) to seconds (i.e., ribosomal translation). These motions are governed by many different interactions acting on the NC, including those associated with the solvent and lipid, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatics. Building an effective CGMD model for this system requires aggressive simplification in order to reach the long timescales of translation, while still retaining enough of the essential physics to reproduce and extend experimental results. Here, we discuss and review a CGMD method9,28 for Sec-facilitated protein biosynthesis that is founded on the hypothesis that the major drivers of translocation are the time-dependent extension of the nascent polypeptide, the conformational opening and closing of the LG, and the hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between the NC and the translocon and lipid membrane. This simplified picture excludes the explicit role of hydrogen bonding and secondary structure, an approximation that can be partially justified by the expected separation of timescales between topology formation and protein folding/compaction.45,46 The current section provides a technical overview of the CGMD method (Fig. 2), highlighting the underlying approximations and physics that is explicitly included or excluded (additional detail can be found in Refs. 9,28). Subsequent sections illustrate how the CGMD method has been validated against available experimental data and used to make experimentally testable predictions.

Figure 2:

CG models that can directly simulate the minute-timescale process of protein synthesis and integration. (A) Frames from a trajectory simulating the integration of a multispanning IMP (red for TMDs and blue elsewhere), using the original 2D version of the CGMD model. The model explicitly captures the sterics and charges from the ribosome (orange) and translocon (pink). The membrane (grey region) and solvent are treated implicitly. (B) Example mapping of an amino-acid sequence into its CG representation. CG beads are composed of three amino acids, and inherit charges (qi) and hydrophobicity (gi) from their constituents. In the 3D model, each bead is also assigned a secondary structure, which affects its interactions with the membrane. (C) Simulation snapshot of the integration of a single-spanning membrane protein (TMD in red, blue elsewhere) using the most recent 3D version of the CGMD model. Panel B is adapted from Ref. 9, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.

Model Geometry

The CGMD model describes the NC as a linear chain of CG beads, each of which represents a trio of amino-acids residues (Fig. 2B). This choice of three amino acids per bead is based on the estimated Kuhn length, which describes the scale at which the nascent polypeptide can be treated as an ideal polymer chain. Each CG bead has a charge and hydrophobicity derived from its component amino acids (Fig. 2B). Solvent is implicitly included via a position dependent potential acting on the NC, where the energy difference between the water and lipid region for a NC particle reflects its hydrophobicity, determined by the Wimley-White water-octanol transfer free energy47 of the corresponding amino acids.

In the original version of the CGMD model,48 the translocon, ribosome, and NC were all described via projection onto a two-dimensional plane (Fig. 2A). More recently,9 this approach has been extended to a full three-dimensional representation with the structure of the ribosome and translocon derived from available cryo-EM data49 (Fig. 2C). The ribosome and translocon are represented using CG beads at the same level of coarse-graining as used for the NC, with three amino acids represented using one CG bead, and each nucleotide represented using two CG beads.

Model Dynamics

During a simulation in which the NC is synthesized via ribosomal translation, new beads are added to the NC at a specified rate, typically 5–20 residues per second. The NC positions, xn(t), evolve according to over-damped Langevin dynamics (Eq. 1),

| (1) |

where xc(t) are the positions of the translocon and ribosome beads at time t, U(xn(t), xc(t)) is the CGMD model potential energy function,9,28 D is an isotropic diffusion coefficient, Δt the simulation timestep, and R(t) is a random number vector drawn from a Gaussian distribution with zero mean and unit variance. The factor DΔt is set to yield stable time-integration. The value of Δt is important in relating CGMD time to real time. It is parameterized by comparing the translocation time of a hydrophobic NC to experiment.28

Conformational gating of the translocon LG is explicitly included in the CGMD model. Contrary to the fully flexible NC beads, the ribosome and translocon beads only have two possible positions, representative of an open and closed translocon channel. The LG of the Sec translocon opens and closes stochastically, using a Monte Carlo move, where the probability of undergoing a conformational change depends on the free energy difference between the two conformations, ΔGopen(xn). For example, the probability for channel opening is given by (Eq. 2),

| (2) |

where the timescale for attempting translocon conformational changes, τLG = 500 ns, is obtained from prior molecular dynamics simulations.7,28 Further discussion, and robustness tests, on the specific values used in these equations are provided in Refs. 28 and 9.

Parameterization of Interactions

Interaction parameters in the CGMD model are determined from a combination of MD simulations of the translocation process7,9 and well-established experiments,47 and are subsequently validated against experiments not used in parameterization (see further sections in this perspective). The timescale and NC-sequence dependence of LG conformational changes was determined using all-atom MD simulations.7,9,48 Solvent interaction energies are taken from experimental measurements of the water to octanol transfer free energy for amino acids,47 the screening length of electrostatic interactions is calculated assuming physiological salt concentration,9 and the CG bead diffusion constant is set by fitting the translocation time of pre-pro-α factor, a hydrophilic NC, to available experimental data.9,28 The parameterization described above has been used throughout the development of the CGMD model, even as the model has been refined from a 2D (Fig. 2A)28 to a 3D representation (Fig. 2C)9 that includes greater structural detail and chemically detailed NC-translocon interactions. Structural detail was added to the CGMD model using recent cryoEM structures of the RNC-translocon complex,49 and chemical detail was added by parameterizing NC-translocon interactions to reproduce the translocation free-energy profiles of model tri-peptides obtained using more detailed simulations (MARTINI FF).9 Because each interaction is parameterized independently, all of the parameters have a physically meaningful interpretation and no experimental data was shared between fitting and validation.

Model Validation

The resulting CGMD model enables straightforward simulation of minute-timescale trajectories of Sec-facilitated co-translational integration and translocation, using only the NC amino-acid sequence as input. A particular advantage of using such a highly coarse-grained model is that it enables the efficient exploration of diverse NC sequences and the role of specific interactions or perturbations. For example, the effect of lumenal biasing factors such as BiP, can be implicitly modeled via a force disfavoring backsliding of the nascent chain.28,50 Other interactions, such as the effects of the transmembrane potential, can also be included via simple additive contributions to the potential energy function.51 Despite the aggressive simplifications employed, extensive benchmarking with respect to experimental results5,13,16,19,52–54 - which is summarized in the following sections - reveals that the CGMD model provides a reasonable description of co-translational integration and secretion. We emphasize that other coarse-graining strategies55–57 could be employed to further refine the CGMD model.

Membrane-protein integration efficiency and topogenesis

Initial applications of the CGMD model focused on validating it against against experiments that use model peptides to determine the effect of well-controlled perturbations on NC membrane integration and translocation. Particularly valuable for this purpose are quantitative biophysical studies of stop transfer efficiency and TMD topogenesis from the groups of von Heijne and Spiess, respectively.13,23 Moreover, as will also be shown, recent experimental studies58 continue to shed light on the mechanism and regulation of TMD topogenesis and to provide a valuable basis for testing the CGMD model.

Following co-translational insertion into the Sec translocon, the substrate NC either integrates into the lipid bilayer (Fig. 3A, red) or translocates across the lipid bilayer (Fig. 3A, blue). For substrates that undergo membrane integration, the orientation of the TMDs with respect to the membrane can be established during the co-translational process (Fig. 3A, red), although as will be detailed later in the context of dual-topology proteins, post-translational reorganization TMDs can also occur.59–62

Figure 3:

The role of energetics and kinetics in co-translational integration and translocation via the Sec translocon. (A) Schematic representation of several possible pathways for the integration (shaded red) and translocation (shaded blue) of a particular domain in a nascent protein sequence (red box). (B) The probability of membrane integration, p(integration), as a function of the number of leucine residues in a model 19-residue TMD (other residues are alanine). Results are shown for experiments13 and CGMD.9 (C) The distribution between the Type 1 integrated and Type 2 integrated product for a model signal sequence. (left) CGMD model simulation results showing the fraction of trajectories that reach the Type 2 topology as a function of the number of C-terminal loop residues, plotted for a normal translational rate (solid black) and a slowed translation rate (dashed red). (right) Experimental results from Göder et al,23 with a normal translation rate (solid black) and with a slowed translation rate (dashed red), due to addition of cycloheximide. Panels B and C are adapted from Ref. 9, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.

We first review the validation of the CGMD model against experiments that probe the effect of the amino-acid sequence on the probability of membrane integration.13 A glycosylation assay has been developed to measure the probability of membrane integration.63 The protein system considered is a construct of the leaderpeptidase (LepB) protein, with a 19-residue model TMD, and the integration efficiency was measured as a function the number of leucine residues that were substituted into the TMD. Experimental studies revealed a trend that is consistent with an apparent two-state equilibrium in which the ratio of the two outcomes is determined by the free energy difference between them (Fig. 3B, black), although the detailed mechanistic origin of this effective equilibrium was unclear. CGMD recapitulates the experimentally observed trend (Fig. 3B, red) within ~1 kcal/mol accuracy of the experiment (Fig. 3B, shaded region). CGMD was further shown to correctly capture the effect on the probability of integration for all twenty naturally occurring amino-acid residues.9 Analysis of the CGMD trajectories reveals that the apparent two-state equilibrium arises from sampling of the lipid environment and channel interior (Fig. 3A, inside dashed box), where the energetic difference between the relevant NC configurations depend on the hydrophobicity of the TMD. Note that CGMD shows a local equilibration between NC configurations that lead to irreversible products states (i.e., secreted in blue and integrated in red), the product states themselves are not in equilibrium. Additionally, the relevant states do not simply correspond to a partitioning of the TMD between a hydrophilic environment and a hydrophobic environment, explaining why the experimentally measured apparent free-energy differences do not directly correspond to other amino-acid hydrophobicity scales.13,15,47,64 Additional experimental work has revealed a positional dependence of individual amino-acid contributions to the apparent free energy of integration,14 the effect of changing the amino-acid context around the TMD,65 and the effect of mutations in the Sec translocon on the apparent free energy of integration,17,18,66 all of which support the mechanistic interpretation from the CGMD simulations in Fig. 3A.

Beyond its role in membrane integration efficiency, the translocon plays an important role in establishing the topology of TMDs upon membrane integration, a process that has been shown to be sensitive to kinetic factors that include the rate of ribosomal translation.23,67 CGMD was validated against experiments that determine the effect on topology (Fig. 3A, red shaded) of changes in the rate of ribosomal translation and the length of the NC soluble domain.23 The experiments focused on a model signal sequence (SS), H1ΔLeu22, and it was found that the probability this SS undergoes integration in the Type 2 orientation(i.e., Cperi/Ncyto) increased for sequences with longer C-terminal loops (Fig. 3C, x-axis) and likewise increased when the rate of ribosomal translation was slowed (Fig. 3C, compare red and black curves).

CGMD simulations were employed to understand how the rate of translation and the C-terminal length affect the probability of reaching a Type 2 topology. Figure 3C shows that CGMD recapitulates both experimentally observed trends. Additionally, analysis of the CGMD trajectories reveals that the Type 1 product is kinetically accessible while reaching the Type 2 product involves crossing a significant barrier for translocation of the C-terminal loop. Increasing the time of ribosomal translation, either by extending the length of the NC or by slowing ribosomal translation, provides more time for crossing this barrier. The simulations also explain the observation that extending the C-terminal loop beyond a certain length no longer improves the probability of the Type 2 product (Fig. 3C, plateau); for long C-terminal loops the SS will be pushed away from the translocon, locking in a final topology before ribosomal translation of the NC is completed.

Very recently, it was found that members of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family require an extra protein complex, the endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein complex (EMC), in order to efficiently initiate topogenesis.58 In both cells and in vitro systems depleted of EMC, the first TMD of many GPCRs fails to integrate correctly into the membrane. Restoring EMC is found to rescue efficient membrane integration, implying that EMC can function as an insertase for the first TMD of some proteins; this is not an alternative integration pathway for the full protein, as integration of subsequent TMDs still relies on the Sec translocon.

The observed activity of EMC presents a challenge for IMP topology prediction. Specifically, it should be expected that the degree to which a given protein is experimentally observed to depend on EMC for successful integration of the first TMD should vary with the degree to which that the simulations predict that first TMD to unsuccessfully integrate in the absence of EMC. Indeed, Fig. 4 demonstrates that the correlation between experiment and simulation is very strong, suggesting that the CGMD model provides a tool for identifying nascent proteins that are intrinsically inefficient at membrane integration and that will more likely require supporting machinery for integration, such as EMC.

Figure 4:

For all seventeen GPCRs studied by Chitwood et al.,58 comparison of the experimentally observed EMC dependence with the CGMD-predicted fraction of incorrect integration for TMD 1.

By reaching biologically relevant timescales, CGMD enables direct comparison with experiments on membrane integration and topogenesis, thereby probing the fundamental steps of multi-spanning integral membrane protein integration. The success of CGMD in reproducing experimental results emphasizes the important interplay of hydrophobic and electrostatics interactions with non-equilibrium kinetic factors in the operation of the Sec translocon.

Misintegration and post-translational topological annealing in the dual-topology protein EmrE

Membrane protein topology formation is tightly connected to co-translational integration and is essential for proper function and expression. Dual-topology proteins, which are present in the cell membrane in two distinct topologies, provide a useful framework for investigating how topology is determined. The prevalence of dual-topology proteins in biology raises fundamental questions about the biophysics of multi-spanning membrane protein integration: At what point during Sec-facilitated integration is the overall topology of a membrane protein established? Can dual-topology proteins flip post-translationally and reach thermodynamic equilibrium or are they kinetically trapped?

The bacterial multidrug transporter, EmrE, is among the most extensively studied dual-topology proteins. EmrE functions only as a anti-parallel dimer, enabling experiments to probe the ratio between the two possible topologies by measuring functional activity. Experiments by the von Heijne group have used such an assay to probe the effect of amino-acid mutations on the ratio of EmrE topologies.16 Remarkably, these experiments show that mutations at the end of the sequence can have a pronounced effect on the topology of EmrE, indicating that topology is still fluid at the end of co-translational integration. However, the process by which these mutations affect topology is unclear, potentially arising from either kinetic or thermodynamic driving forces. Mutations could change the thermodynamic equilibrium between the two final topologies, or they could affect the process of co-translational insertion and lead to different kinetically accessible outcomes.

CGMD was employed to simulate the effect of the mutations throughout the EmrE sequence on co-translational integration and topogenesis. Trajectories were terminated after NC translation was completed and the NC was in one of the two possibly fully integrated topologies (Ncyto/Ccyto or Nperi/Cperi), importantly, not allowing thermodynamic equilibration of the final topologies. Ratios between the two final topologies for each mutant sequence were computed by simulating the co-translational integration of each sequence with 250 independent CGMD trajectories.

The simulations agree remarkably well with the experimental data (Fig. 5A); within statistical error, CGMD correctly predicted the dominant topology in all but one of the 16 protein mutations considered.59 Analysis of the CGMD trajectory data yields a mechanism that can explain the striking effect of amino-acid mutations on the resulting fully integrated topology of EmrE, without invoking the wholesale flipping of EmrE (i.e., interconversion of the fully integrated Ncyto/Ccyto topology to the fully integrated Nperi/Cperi topology, or vice versa), which is presumed to be kinetically unfavorable. CGMD reveals that the experimentally studied mutations primarily affect the localization of the mutated loop (i.e., whether or not it is translocated across the membrane). If this localization is inconsistent with the topology of the preceding TMDs, EmrE will arrive in a misintegrated state (Fig. 5B, left). These misintegrated states kinetically anneal over time into a fully integrated topology (Fig. 5B, left to right), in part due to the low barrier of flipping the short hydrophilic loops in EmrE across the lipid membrane. The final integrated state is predominantly determined by the location of the slowest-flipping (i.e., most hydrophilic) loop at the end of translation (Fig. 5C). Since the studied mutations involve the introduction of strongly hydrophilic charged residues, the loop with the mutation is typically the slowest-flipping and thus determines the final fully integrated topology. This explanation for the observed sequence dependence of EmrE topology, determined using CGMD, agrees with available experimental data16,60 and only involves local TMD flipping moves that are kinetically accessible; this mechanism avoids the need to invoke wholesale flipping of EmrE from one final topology to the other.

Figure 5:

The post-translational ensemble of the dual-topology protein EmrE determines the final fully integrated topology via topological annealing. (A) Single residue mutations can change the ratio of fully integrated topologies for EmrE, relative to the roughly equal distribution observed for the wildtype sequence (left most pair of bars). The shift in the ratio of the fully integrated topologies obtained using CGMD (blue)59 agrees qualitatively with experiment (black).16 The mutated residue is indicated using a purple dot in the schematics, with the schematic drawn in the dominant topology as determined using CGMD. (B) CGMD simulations suggest a mechanism via which mutations late in the NC sequence affect the final topology; there is a strong correlation between the end-of-translation topology (left) and the fully integrated topology (right). The location of the slowest-flipping loop (purple) in the end-of-translation topology determines the final topology. (C) A quantification of the effect shown schematically in part (B). Figure adapted from Ref. 59, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.

The proposed mechanism from the CGMD simulations, in which a post-translational ensemble of misintegrated states undergoes kinetically driven annealing to reach fully integrated topologies (Fig. 5B), has been supported by subsequent experimental work. Experiments by Bowie and co-workers have shown that a mutated version of EmrE locked into a Cin topology can be reverted to a Cout topology by cleaving the mutated C-terminus.68 This observation was initially proposed to provide support for wholesale filling in EmrE; however, since the only experimental read-out is the presence of the functional anti-parallel EmrE dimer, the results are also consistent with the topological annealing mechanism proposed by CGMD. Indeed, subsequent experimental work has found that wholesale flipping does not occur in EmrE;61 instead, the topology is determined co-translationally or shortly after translation, as predicted by CGMD.

Revealing forces on nascent polypeptides during translation

During translation, emerging NCs experience a range of molecular interactions that determine their fate in the cell. Measuring these interactions and determining which ones are dominant at different stages of translation is challenging due to the complexity of the co-translational environment. Yet, an understanding of the molecular interactions that govern co-translational processing via the Sec translocon is essential for the design of modifications that alter the outcome of this process.69 A promising method for measuring co-translational forces in an in vivo environment relies on arrest-peptides (AP) which stall translation at a precisely definable location.70 If the NC experiences a force of sufficient magnitude then translation restarts, providing an easy read-out.19,54,71 However, gaining molecular-level in sight through this technique is still difficult and requires measuring forces from many different constructs and well-thought-out controls. A combination of AP experiments with CGMD simulations of the same NCs provides a compelling strategy; CGMD provides a clear mechanistic interpretation, while direct comparison to AP experiments alleviates any concerns due to the approximations inherent to simulation. The synergy of AP experiments and CGMD has already been used to shed light on co-translational NC folding,72 NC-translocon interactions, NC-solvent interactions, coupling of charged residues to the transmembrane potential in E. coli, and translocon lateral gating.51

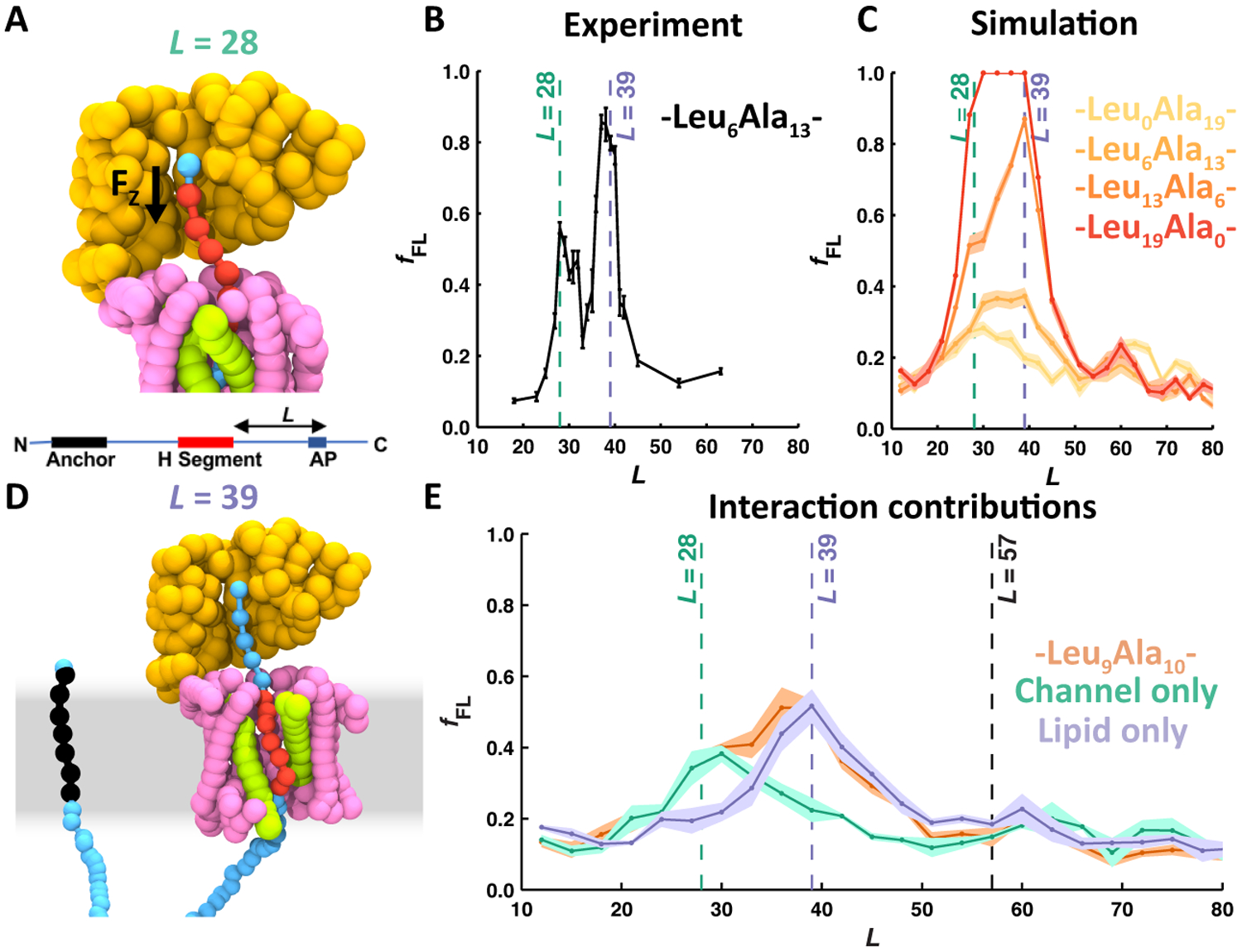

Figure 6 shows how CGMD can be combined with AP experiments to investigate the molecular interactions acting on a NC during the co-translational integration of a model TMD via the Sec translocon. The NC consists of a 19-residue model TMD (H segment), containing varying amounts of leucine and alanine residues, inserted into a LepB construct.19 An AP is placed at varying distance, L (number of residues), downstream of the H segment (Fig. 6A, bottom). The experiment measures the probability of AP stall-breaking as a function of L (Fig. 6B) and reveals two clear peaks in force, at L = 28 and L = 39. CGMD is used to directly calculate the force on the C-terminal bead of the NC from trajectories with translations halted at various NC lengths, corresponding to specific values of L. Calculated forces are then used to determinate a probability of stall-breaking that can be compared with the experimental data (see Ref. 51 for details) (Fig. 6C). CGMD predicts increased force on the NC at values of L consistent with the AP experiments. Furthermore, by comparing trajectory data at L = 28 (Fig. 6A) and L = 39 (Fig. 6D), the molecular interactions that are responsible for the force exerted on the NC can be identified. The peak at L = 28 was found to be due to attractive interactions between the NC and the amphiphilic channel interior, and the peak at L = 39 was found to be due to partitioning of the hydrophobic TMD into the lipid membrane. Precise control on the simulation parameters enable additional simulations with modified interactions that further confirm the proposed molecular mechanism underpinning the two peaks in force that were experimentally observed (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6:

Revealing the molecular interactions that act on TMDs during their co-translational integration, using a combined CGMD and AP experiment approach. (A) Simulation snapshot indicating the force acting on the part of the NC at the top of the exit tunnel (black arrow) and a schematic depiction of the NC construct used in the presented simulations and experiments (bottom). The snapshot is for the construct with L = 28, coinciding with the first point during translation at which a significant pulling force is exerted on the NC. (B) Pulling-force profile determined using AP experiments; plotted is the fraction of full-length protein, fFL, as a function of L. Two peaks in force are observed, at L = 28 and L = 39. (C) Pulling-force profile determined using CGMD simulations; plotted in the same way as panel (B). Colors indicate data for H segments with varying amounts of hydrophobic leucine residues. (D) Simulation snapshot at L = 39, coinciding with the second peak in force on the NC. (E) Pulling-force profiles determined using CGMD, for simulations with full interactions (orange), without specific interactions between the NC and the lipid membrane (green), and without specific interactions between the NC and the translocon (purple). These data reveal that the first peak in force depends specifically on NC-translocon interactions, while the second peak in force depends specifically on NC-lipid interactions. Figure adapted with permission from Ref. 51, copyright 2018 Biophysical Society.

The combination of CGMD with AP experiments has also helped to resolve the molecular interactions that act on hydrophilic and short hydrophobic segments that translocate across the membrane.51 Hydrophilic peptides were shown to experience forces due to changes in solvation, charged peptides experience forces due to interaction with the ribosomal RNA and coupling to the transmembrane potential, and short hydrophobic segments experience forces due to interaction with the translocon and the lipid membrane. Future work using this methodology could provide insight into the integration of multispanning membrane proteins and the co-translational interaction of NCs with previously integrated TMDs or other cofactors.

Enabling the heterologous overexpression of membrane proteins by improving their co-translational integration efficiency

Recent years have seen a dramatic increase in the pace of discovery in research and medicine. A key driver in this progress has been the availability of large amounts of recombinantly expressed proteins, which has enabled an exponential rise in structural information and a protein structure database with over 100,000 structures. Unfortunately, the understanding of IMPs lags far behind that of soluble proteins, due to the fact that only a small percentage of IMPs can be expressed (i.e., heterologously produced at levels conducive to further study).73 Given the prevalence of IMPs (a quarter of all protein-coding genes) and predominance of IMPs as pharmaceutical targets (60% of all drug targets),74 IMP expression levels constitute a major impediment to the advancement of both fundamental scientific objectives and medical priorities.75

The major limitation to IMP expression is a poor understanding of the biological principles that underlie the differences seen in levels of expression. At the heart of this challenge is the extraordinary array of factors that potentially impact IMP expression,75,76 including dozens of properties that range from those affecting the translation and targeting machinery to the physicochemical properties of the amino-acid sequences that dictate membrane insertion and IMP folding. While case-specific sequence optimization, using trial-and-error77 and directed evolution approaches,78 has shown that IMP expression levels can be improved, they do not provide transferable design principles based on a clear mechanism.

CGMD and experimental measurements were combined to demonstrate that membrane integration efficiency is an important bottleneck in the heterologous overexpression of the IMP TatC.5 CGMD demonstrated that sequence modifications can alter the balance between correctly integrated and misintegrated topologies of TatC (Fig. 7A), in agreement with the effect of those same sequence modifications on expression levels (Fig. 7B,C).53 Further experiments, utilizing a C-terminal β-lactamase tag to directly measure the CGMD-predicted misfolded product (Fig. 7A, right), confirm the mechanism proposed by CGMD; that sequence modifications affect expression levels by changing the probability of correct integration. Under exposure to ampicillin, cell survival is dependent on the translocation of the C-terminal β-lactamase tag, and thus TatC misintegration. Consistently, cell survival is negatively correlated with expression (Fig .7D), experimentally verifying the effect of sequence modifications on TatC topology that CGMD predicted.

Figure 7:

The simulated integration efficiency of TatC mutants is predictive of their expression levels. (A) Simulated integration efficiency is determined by the probability of the soluble loops (cyan) being correctly localized during CGMD co-translational integration. In the case of TatC, the C-terminal loop was found to often mislocalize, as shown in the schematic. (B) Integration and expression levels of different homologs and chimeras of TatC. Values are reported relative to the Aquifex aeolicus homolog. (C) Receiver operating characteristic of integration as a predictor for expression. Data are from 152 different mutants of TatC. (D) The survival and expression levels of 14 different mutants of TatC, each with a β-lactamase domain on the C-terminus, such that the cell can only survive if TatC misintegrates with its C-terminus in the periplasm. (E) The expression and integration values are shown for a series of TatC constructs with decreasing amounts of positive charge in the C-terminal tail. Panels C and D are adapted with permission from Ref. 53, copyright the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Panel E is adapted from Ref. 5, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY license.

CGMD also provides insights that enable the rational design of sequence modifications that improve IMP expression. As an example, the initial set of mutants simulated for TatC suggested that integration efficiency of TatC is dependent on the charge of the C-terminal loop. Consistently, expression levels of TatC were found to decrease monotonously upon removal of charged residues from the C-terminal loop (Fig. 7E). CGMD was also used to demonstrate that sequence modifications that enhance integration efficiency and expression are additive,53 enabling the design of sequences with dramatically higher expression than the wild-type without incurring the combinatorial cost typically associated with screening multiple simultaneous sequence modifications.

The close relationship identified between IMP integration and expression holds the potential to expand the number of accessible IMPs for biochemical and structural characterization. This is especially critical given the current under-characterization of IMPs relative to soluble proteins,73 despite their great biochemical and pharmacological significance.74 The ability for a greater understanding of Sec-mediated integration and translocation to mitigate low integration efficiency as a key limiting step in the overexpression of IMPs will hopefully serve to motivate continual development of the field.

Conclusions & Outlook

The targeting, delivery, and folding of newly synthesized proteins in complex cellular environments offers a rich problem area from both fundamental and practical perspectives. IMPs are particularly notable for the challenges and opportunities that they present, motivating the development of improved experimental and theoretical tools. The current perspective describes the development and application of a coarse-grained model that enables the direct simulation of co-translational membrane integration and translocation of proteins via the Sec translocon on biological timescales. The approach has been shown to yield new insights into the molecular mechanisms that govern the fate of nascent proteins in the cell. In particular, it has helped to elucidate the effects of sequence, translation rate, and external forces on the probability of nascent-chain integration into the membrane and the resulting orientation of TMDs with respect to the membrane. Furthermore, this approach has helped to uncover a link between correct IMP integration and the downstream expression levels, providing a promising strategy for the design of well-expressing IMP sequences.

Looking forward, there are many open questions in membrane protein biogenesis to which physics-based simulation models may contribute. Specific examples pertain to the mechanism of the Sec translocon itself,49,79,80 as well as to the interplay between a nascent membrane protein and its environment – including collaborating molecular machinery58,81,82 – in determining topology and structure. The development of a more complete understanding of the interactions between TMDs and the role they play in topology formation will strengthen the important connections between membrane protein integration, topogenesis, folding, and expression. Computational methods such as those described here will help to clarify these connections, as well as to guide and interpret future experimental studies.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM125063) and the Office of Naval Research (N00014-16-1-2761). Computational resources were provided by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, which is supported by National Science Foundation grant No. ACI-1548562.

References

- (1).Rapoport TA Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature 2007, 450, 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).White SH; von Heijne G How translocons select transmembrane helices. Annu. Rev. Biophys 2008, 37, 23–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).von Heijne G Membrane-protein topology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2006, 7, 909–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Cymer F; Von Heijne G; White SH Mechanisms of integral membrane protein insertion and folding. J. Mol. Biol 2015, 427, 999–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Marshall SS; Niesen MJM; Müller A; Tiemann K; Saladi SM; Galimidi RP; Zhang B; Clemons WM Jr; Miller TF III A Link Between Integral Membrane Protein Expression and Simulated Integration Efficiency. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 2169–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Berg BVD; Clemons WM Jr; Collinson I; Modis Y; Hartmann E; Harrison SC; Rapoport TA X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel. Nature 2004, 427, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zhang B; Miller TF III Hydrophobically stabilized open state for the lateral gate of the Sec translocon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2010, 107, 5399–5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Voorhees RM; Fernández IS; Scheres SHW; Hegde RS Structure of the mammalian ribosome-Sec61 complex to 3.4 A resolution. Cell 2014, 157, 1632–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Niesen MJM; Wang CY; Van Lehn RC; Miller TF III Structurally detailed coarse-grained model for Sec-facilitated co-translational protein translocation and membrane integration. PLOS Comp. Biol 2017, 13, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Tsirigotaki A; De Geyter J; Šoštaric N; Economou A; Karamanou S Protein export through the bacterial Sec pathway. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2016, 15 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Denks K; Vogt A; Sachelaru I; Petriman NA; Kudva R; Koch HG The Sec translocon mediated protein transport in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Mol. Membr. Biol 2014, 31, 58–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gogala M; Becker T; Beatrix B; Armache J-P; Barrio-Garcia C; Berninghausen O; Beckmann R Structures of the Sec61 complex engaged in nascent peptide translocation or membrane insertion. Nature 2014, 506, 107–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hessa T; Kim H; Bihlmaier K; Lundin C; Boekel J; Andersson H; Nilsson I; White SH; von Heijne G Recognition of transmembrane helices by the endoplasmic reticulum translocon. Nature 2005, 433, 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hessa T; Meindl-Beinker NM; Bernsel A; Kim H; Sato Y; Lerch-Bader M; Nilsson I; White SH; von Heijne G Molecular code for transmembrane-helix recognition by the Sec61 translocon. Nature 2007, 450, 1026–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Öjemalm K; Higuchi T; Jiang Y; Langel Ü; Nilsson I; White SH; Suga H; von Heijne G Apolar surface area determines the efficiency of translocon-mediated membrane-protein integration into the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108, 359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Seppälä S; Slusky JS; Lloris-Garcerá P; Rapp M; von Heijne G Control of Membrane Protein Topology by a Single C-Terminal Residue. Science 2010, 328, 1698–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Junne T; Kocik L; Spiess M The Hydrophobic Core of the Sec61 Translocon Defines the Hydrophobicity Threshhold for Membrane Integration. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 1662–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Demirci E; Junne T; Baday S; Bernèche S; Spiess M Functional asymmetry within the Sec61p translocon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2013, 110, 18856–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ismail N; Hedman R; Schiller N; von Heijne G A biphasic pulling force acts on transmembrane helices during translocon-mediated membrane integration. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2012, 19, 1018–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gumbart J; Schulten K Structural Determinants of Lateral Gate Opening in the Protein Translocon. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 11147–11157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tsirigos KD; Govindarajan S; Bassot C; Västermark Å; Lamb J; Shu N; Elofsson A Topology of membrane proteins – predictions, limitations and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2018, 50, 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).von Heijne G Membrane protein structure prediction: Hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J. Mol. Biol 1992, 225, 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Goder V; Spiess M Molecular mechanism of signal sequence orientation in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 3645–3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gumbart JC; Chipot C Decrypting protein insertion through the translocon with free-energy calculations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. - Biomem 2016, 1858, 1663 – 1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Capponi S; Heyden M; Bondar A-N; Tobias DJ; White SH Anomalous behavior of water inside the SecY translocon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2015, 112, 9016–9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Trovato F; O’Brien EP Insights into Cotranslational Nascent Protein Behavior from Computer Simulations. Annu. Rev. Biophys 2016, 45, 345–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rychkova A; Warshel A Exploring the nature of the translocon-assisted protein insertion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2013, 110, 495–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhang B; Miller TF III Long-Timescale Dynamics and Regulation of Sec-Facilitated Protein Translocation. Cell Rep. 2012, 2, 927–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Elcock AH Molecular Simulations of Cotranslational Protein Folding: Fragment Stabilities, Folding Cooperativity, and Trapping in the Ribosome. PLOS Comp. Biol 2006, 2, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kirmizialtin S; Ganesan V; Makarov DE Translocation of a beta-hairpin-forming peptide through a cylindrical tunnel. J. Chem. Phys 2004, 121, 10268–10277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ziv G; Haran G; Thirumalai D Ribosome exit tunnel can entropically stabilize alpha-helices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2005, 102, 18956–18961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kudva R; Tian P; Pardo-Avila F; Carroni M; Best RB; Bernstein HD; von Heijne G The shape of the bacterial ribosome exit tunnel affects cotranslational protein folding. eLife 2018, 7, e36326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Contreras Martínez LM; Martínez-Veracoechea FJ; Pohkarel P; Stroock AD; Escobedo FA; DeLisa MP Protein translocation through a tunnel induces changes in folding kinetics: A lattice model study. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2006, 94, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).O’Brien EP; Stan G; Thirumalai D; Brooks BR Factors Governing Helix Formation in Peptides Confined to Carbon Nanotubes. Nano Letters 2008, 8, 3702–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).O’Brien EP; Hsu S-TD; Christodoulou J; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM Transient Tertiary Structure Formation within the Ribosome Exit Port. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 16928–16937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Morrissey MP; Ahmed Z; Shakhnovich EI The role of cotranslation in protein folding: a lattice model study. Polymer 2004, 45, 557–571. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Ciryam P; Morimoto RI; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM; O’Brien EP In vivo translation rates can substantially delay the cotranslational folding of the Escherichia coli cytosolic proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2013, 110, E132–E140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Saunders R; Mann M; Deane CM Signatures of co-translational folding. Biotechnol. J 2011, 6, 742–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tian P; Steward A; Kudva R; Su T; Shilling PJ; Nickson AA; Hollins JJ; Beckmann R; Von Heijne G; Clarke J et al. Folding pathway of an Ig domain is conserved on and off the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2018, 115, E11284–E11293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).O’Brien EP; Vendruscolo M; Dobson CM Kinetic modelling indicates that fast-translating codons can coordinate cotranslational protein folding by avoiding misfolded intermediates. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Rychkova A; Mukherjee S; Bora RP; Warshel A Simulating the pulling of stalled elongated peptide from the ribosome by the translocon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2013, 110, 10195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Haider S; Hall BA; Sansom MSP Simulations of a Protein Translocation Pore: SecY. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 13018–13024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Gumbart J; Chipot C; Schulten K Free-energy cost for translocon-assisted insertion of membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108, 3596–3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Rychkova A; Vicatos S; Warshel A On the energetics of translocon-assisted insertion of charged transmembrane helices into membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2010, 107, 17598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Engelman DM; Chen Y; Chin CN; Curran AR; Dixon AM; Dupuy AD; Lee AS; Lehnert U; Matthews EE; Reshetnyak YK et al. Membrane protein folding: beyond the two stage model. FEBS Lett. 2003, 555, 122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Bowie JU Solving the membrane protein folding problem. Nature 2005, 438, 581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Wimley WC; White SH Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nature 1996, 3, 842–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Zhang B; Miller TF III Direct simulation of early-stage Sec-facilitated protein translocation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 13700–13707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Voorhees RM; Hegde RS Structure of the Sec61 channel opened by a signal sequence. Science 2016, 351, 88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Matlack KES; Misselwitz B; Plath K; Rapoport TA BIP acts as a molecular ratchet during posttranslational transport of prepro-α factor across the ER membrane. Cell 1999, 97, 553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Niesen MJ; Müller-Lucks A; Hedman R; von Heijne G; Miller TF III Forces on Nascent Polypeptides during Membrane Insertion and Translocation via the Sec Translocon. Biophys. J 2018, 115, 1885–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Goder V; Spiess M Topogenesis of membrane proteins: Determinants and dynamics. FEBS Lett. 2001, 504, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Niesen MJM; Marshall SS; Miller TF III; Clemons WM Jr Improving membrane protein expression by optimizing integration efficiency. J. Biol. Chem 2017, 292, 19537–19545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Ismail N; Hedman R; Lindén M; von Heijne G Charge-driven dynamics of nascent-chain movement through the SecYEG translocon. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2015, 22, 145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Madsen JJ; Sinitskiy AV; Li J; Voth GA Highly Coarse-Grained Representations of Transmembrane Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2017, 13, 935–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Wagner JW; Dannenhoffer-Lafage T; Jin J; Voth GA Extending the range and physical accuracy of coarse-grained models: Order parameter dependent interactions. J. Chem. Phys 2017, 147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Shell MS Adv. Chem. Phys; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016; Vol. 161; pp 395–441. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Chitwood PJ; Juszkiewicz S; Guna A; Shao S; Hegde RS EMC Is Required to Initiate Accurate Membrane Protein Topogenesis. Cell 2018, 175, 1507–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Van Lehn RC; Zhang B; Miller TF III Regulation of multispanning membrane protein topology via post-translational annealing. eLife 2015, 4, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Woodall NB; Yin Y; Bowie JU Dual-topology insertion of a dual-topology membrane protein. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 8099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Fluman N; Tobiasson V; von Heijne G Stable membrane orientations of small dual-topology membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2017, 114, 7987–7992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Dowhan W; Bogdanov M Lipid-Dependent Membrane Protein Topogenesis. Ann. Rev. Biochem 2009, 78, 515–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Sääf A; Wallin E; von Heijne G Stop-transfer function of pseudo-random amino acid segments during translocation across prokaryotic and eukaryotic membranes. Eur.J. Biochem 1998, 251, 821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Moon CP; Fleming KG Side-chain hydrophobicity scale derived from transmembrane protein folding into lipid bilayers. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 2011, 108, 10174–10177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Hedin LE; Ojemalm K; Bernsel A; Hennerdal A; Illergard K; Enquist K; Kauko A; Cristobal S; von Heijne G; Lerch-Bader M et al. Membrane Insertion of Marginally Hydrophobic Transmembrane Helices Depends on Sequence Context. J. Mol. Biol 2010, 396, 221 – 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Trueman SF; Mandon EC; Gilmore R A gating motif in the translocation channel sets the hydrophobicity threshold for signal sequence function. J. Cell Biol 2012, 199, 907–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Devaraneni PK; Conti B; Matsumura Y; Yang Z; Johnson AE; Skach WR Stepwise insertion and inversion of a type II signal anchor sequence in the ribosome-Sec61 translocon complex. Cell 2011, 146, 134–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Woodall NB; Hadley S; Yin Y; Bowie JU Complete topology inversion can be part of normal membrane protein biogenesis. Prot. Sci 2017, 26, 824–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Harrington HR; Zimmer MH; Chamness LM; Nash V; Penn WD; Miller TF III; Mukhopadhyay S; Schlebach JP Cotranslational Folding Stimulates Programmed Ribosomal Frameshifting in the Alphavirus Structural Polyprotein. bioRxiv 2019, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (70).Goldman DH; Kaiser CM; Milin A; Righini M; Tinoco I; Bustamante C Mechanical force releases nascent chain–mediated ribosome arrest in vitro and in vivo. Science 2015, 348, 457–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Ito K; Chiba S; Pogliano K Divergent stalling sequences sense and control cellular physiology. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2010, 393, 1 – 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Leininger SE; Trovato F; Nissley DA; O’Brien EP Domain topology, stability, and translation speed determine mechanical force generation on the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2019, 116, 201813003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Lewinson O; Lee AT; Rees DC The Funnel Approach to the Precrystallization Production of Membrane Proteins. J. Mol. Biol 2008, 377, 62 – 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Overington JP; Al-Lazikani B; Hopkins AL How many drug targets are there? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2006, 5, 993–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Wagner S; Bader ML; Drew D; de Gier J-W Rationalizing membrane protein overexpression. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 364 – 371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Nørholm MH; Light S; Virkki MT; Elofsson A; von Heijne G; Daley DO Manipulating the genetic code for membrane protein production: What have we learnt so far? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. - Biomem 2012, 1818, 1091 – 1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Punta M; Love J; Handelman S; Hunt JF; Shapiro L; Hendrickson WA; Rost B Structural genomics target selection for the New York consortium on membrane protein structure. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 2009, 10, 255–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Klenk C; Ehrenmann J; Schtz M; Plückthun A A generic selection system for improved expression and thermostability of G protein-coupled receptors by directed evolution. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 21294–21294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Jomaa A; Boehringer D; Leibundgut M; Ban N Structures of the E. coli translating ribosome with SRP and its receptor and with the translocon. Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Fessl T; Watkins D; Oatley P; Allen WJ; Corey RA; Horne J; Baldwin SA; Radford SE; Collinson I; Tuma R Dynamic action of the SEc machinery during during initiation , protein translocation and termination. eLife 2018, 7, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Samuelson JC; Chen M; Jiang F; Möller I; Wiedmann M; Kuhn A; Phillips GJ; Dalbey RE YidC mediates membrane protein insertion in bacteria. Nature 2000, 406, 637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Tsukazaki T; Mori H; Echizen Y; Ishitani R; Fukai S; Tanaka T; Perederina A; Vassylyev DG; Kohno T; Maturana AD et al. Structure and function of a membrane component SecDF that enhances protein export. Nature 2011, 474, 235–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]