Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with preterm birth, infant sleep and temperament at 1 month of age. We used the data of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study, a cohort study in Japan, which registered 103,099 pregnancies between 2011 and 2014. Participants were asked about their sleep before and during pregnancy, and the sleep and temperament of their newborns at 1 month of age. Preterm birth data were collected from medical records. Maternal sleep was not associated with preterm birth, but subjective sleep quality during pregnancy was associated with late preterm birth (birth at 34–36 weeks of gestation). For example, participants with extremely light subjective depth of sleep were more likely to experience preterm birth (RR = 1.19; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.04–1.35). Maternal sleep both before and during pregnancy seemed to be associated with infant sleep and temperament at 1 month of age. Infants, whose mothers slept for less than 6 hours before pregnancy, tended to cry intensely (RR = 1.15; 95% CI = 1.09–1.20). Maternal sleep problems before and during pregnancy were associated with preterm birth and child sleep problems and temperament.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Risk factors

Introduction

In Japan, the average sleep duration is shorter than in other countries1, and it has become even shorter in recent years2. At the same time, the rate of preterm birth in Japan has increased3, as has the incidence of developmental disorders4.

Maternal short sleep duration and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) are associated with increased preterm birth rates5,6. Furthermore, maternal SDB and apnea during pregnancy affects offspring’s development, manifesting as disrupted social skills and low reading test scores7,8.

However, no large-scale study has examined potential associations between sleep during pregnancy and offspring’s development. Additionally, the importance of maternal sleep during various periods of pregnancy remains unclear. Maternal short sleep and SDB increase inflammatory cytokine levels9,10, and maternal inflammation can cause preterm birth11,12 and developmental disorder13,14. Maternal obesity also increases inflammatory cytokines15,16, and a study reported that maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) affects maternal inflammatory markers to a greater extent than does late pregnancy BMI17. Similarly, maternal sleep before pregnancy may also be more important for obstetric outcomes and offspring development than sleep during pregnancy.

In cases of neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), abnormalities of neurodevelopment, sleep, and temperament are observed in early infancy, such as a 1–4-month-old18,19. This study aimed to investigate the association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with preterm birth, infant sleep, and temperament at 1 month of age.

Results

The baseline characteristics of participants, along with available data on sleep duration before and during pregnancy, are shown in Table 1. The most commonly reported sleep duration was 7–8 h both before and during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (2011–2014).

| No. of womena | Sleep duration during preconception (h) | No. of womena | Sleep duration during pregnancy (h) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 6 | 6–7 | 7–8 | 8–9 | 9–10 | > 10 | < 6 | 6–7 | 7–8 | 8–9 | 9–10 | > 10 | |||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |||

| No. of women | 87,106 | 6,028 | 17,260 | 29,350 | 21,521 | 8,830 | 4,117 | 86,358 | 4,305 | 12,948 | 26,769 | 24,491 | 12,166 | 5,679 |

| Age at delivery (years) | ||||||||||||||

| < 25 | 8,499 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 9.3 | 12.4 | 27.1 | 8,465 | 11.7 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 11.1 | 22.7 |

| 25–29 | 24,039 | 25.5 | 26.8 | 27.6 | 27.9 | 28.7 | 30.3 | 23,838 | 25.4 | 26.3 | 27.2 | 27.7 | 28.6 | 31.6 |

| 30–34 | 30,809 | 32.0 | 35.4 | 36.5 | 36.5 | 35.3 | 26.6 | 30,591 | 31.3 | 34.3 | 36.3 | 36.7 | 36.7 | 28.8 |

| ≥ 35 | 23,759 | 32.2 | 30.2 | 28.0 | 26.3 | 23.6 | 16.0 | 23,464 | 31.5 | 30.8 | 28.5 | 27.2 | 23.7 | 16.9 |

| Smoking habits | ||||||||||||||

| Never-smokers | 50,646 | 52.8 | 60.3 | 60.4 | 58.4 | 55.8 | 46.4 | 50,269 | 53.7 | 59.5 | 60.1 | 59.1 | 56.7 | 50.3 |

| Ex-smokers who quit before pregnancy | 20,358 | 20.7 | 21.7 | 23.0 | 24.7 | 26.1 | 24.8 | 20,184 | 21.3 | 21.8 | 22.7 | 24.0 | 25.6 | 24.6 |

| Smokers during early pregnancy | 15,979 | 26.4 | 18.1 | 16.6 | 16.9 | 18.1 | 28.8 | 15,788 | 25.0 | 18.7 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 17.7 | 25.1 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||||

| Never-drinkers | 29,955 | 31.9 | 32.8 | 34.2 | 35.8 | 36.0 | 35.7 | 29,702 | 33.0 | 33.6 | 34.1 | 34.8 | 35.3 | 35.1 |

| Ex-drinkers who quit before pregnancy | 16,233 | 17.1 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 19.7 | 22.5 | 21.7 | 15,767 | 17.9 | 16.2 | 17.6 | 18.4 | 20.7 | 21.1 |

| Drinkers during early pregnancy | 40,885 | 51.1 | 50.5 | 48.0 | 44.6 | 41.5 | 42.7 | 40,859 | 49.2 | 50.2 | 48.4 | 46.8 | 44.0 | 43.9 |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||||||||||

| < 18.5 | 14,045 | 15.8 | 16.1 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 15.8 | 18.0 | 13,969 | 16.9 | 15.9 | 16.0 | 15.8 | 16.7 | 17.6 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 63,883 | 72.4 | 73.8 | 73.6 | 73.5 | 73.3 | 71.0 | 63,334 | 71.4 | 73.7 | 74.0 | 73.9 | 72.4 | 71.3 |

| ≥ 25.0 | 9,140 | 11.8 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 10.9 | 11.0 | 9,000 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 |

| Parity | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 37,911 | 57.8 | 57.6 | 47.3 | 32.1 | 24.1 | 41.0 | 37,640 | 55.3 | 57.0 | 48.7 | 36.5 | 29.1 | 44.0 |

| ≥ 1 | 48,900 | 42.2 | 42.4 | 52.7 | 67.9 | 75.9 | 59.0 | 48,407 | 44.7 | 43.0 | 51.3 | 63.5 | 70.9 | 56.0 |

| Current history | ||||||||||||||

| Diabetes or gestational diabetes | 2,665 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2,638 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy | 2,759 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2,618 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Intrauterine infection | 612 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 554 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| History of preterm birth | ||||||||||||||

| No | 84,156 | 97.0 | 97.1 | 96.8 | 96.3 | 95.8 | 96.7 | 83,518 | 97.0 | 96.9 | 97.0 | 96.6 | 96.4 | 96.6 |

| Yes | 2,934 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2,799 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Infertility treatment | ||||||||||||||

| No | 81,311 | 92.8 | 92.0 | 92.7 | 94.1 | 95.8 | 96.4 | 80,638 | 93.3 | 91.7 | 92.7 | 93.7 | 95.2 | 95.9 |

| Ovulation stimulation/artificial insemination by sperm from husband | 3,158 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 3,109 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| Assisted reproductive technology | 2,609 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2,553 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Educational background, years | ||||||||||||||

| < 13 | 30,964 | 40.4 | 32.9 | 33.8 | 35.4 | 40.1 | 54.2 | 31,045 | 42.6 | 34.9 | 33.4 | 34.7 | 37.8 | 48.9 |

| ≥ 13 | 54,926 | 59.6 | 67.1 | 66.2 | 64.6 | 59.9 | 45.8 | 54,986 | 57.4 | 65.1 | 66.6 | 65.3 | 62.2 | 51.1 |

| Household income, million Japanese-yen/year | ||||||||||||||

| < 6 | 58,726 | 71.3 | 69.5 | 71.1 | 74.6 | 79.3 | 86.1 | 58,763 | 73.9 | 69.6 | 70.3 | 73.1 | 77.6 | 84.9 |

| ≥ 6 | 21,569 | 28.7 | 30.5 | 28.9 | 25.4 | 20.8 | 14.0 | 21,590 | 26.1 | 30.4 | 29.7 | 26.9 | 22.4 | 15.1 |

| Occupation in early pregnancy | ||||||||||||||

| Administrative, managerial, professional, and engineering workers | 20,047 | 22.0 | 26.3 | 25.5 | 22.9 | 17.1 | 9.7 | 19,798 | 20.2 | 24.7 | 25.7 | 24.4 | 19.6 | 12.9 |

| Clerical workers | 14,816 | 18.8 | 21.4 | 19.6 | 14.8 | 10.0 | 6.9 | 14,580 | 17.7 | 21.2 | 19.7 | 16.3 | 12.3 | 8.9 |

| Sales and service workers | 19,105 | 25.0 | 20.7 | 20.2 | 22.6 | 24.2 | 30.4 | 18,858 | 25.4 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 22.0 | 24.0 | 28.9 |

| Homemaker | 24,024 | 22.3 | 22.0 | 25.3 | 30.6 | 38.8 | 39.8 | 23,688 | 24.2 | 23.8 | 25.1 | 28.2 | 34.5 | 36.1 |

| Others | 8,472 | 11.8 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.9 | 13.2 | 8,360 | 12.5 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 13.2 |

| Type of delivery | ||||||||||||||

| Vaginal | 70,776 | 79.8 | 81.1 | 81.2 | 82.0 | 82.3 | 81.8 | 70,603 | 81.9 | 81.4 | 81.6 | 81.9 | 82.9 | 82.4 |

| Caesarean | 16,143 | 20.2 | 18.9 | 18.8 | 18.0 | 17.7 | 18.2 | 15,582 | 18.1 | 18.6 | 18.4 | 18.1 | 17.1 | 17.6 |

| Postpartum depressive symptoms at 1 month after delivery assessed by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale | ||||||||||||||

| Not depressive (score < 8) | 72,482 | 82.2 | 85.2 | 86.3 | 87.2 | 86.7 | 80.7 | 72,137 | 80.1 | 84.7 | 86.0 | 87.3 | 87.1 | 82.7 |

| Depressive (score ≥ 9) | 11,985 | 17.8 | 14.8 | 13.7 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 19.3 | 11,916 | 19.9 | 15.3 | 14.0 | 12.7 | 12.9 | 17.3 |

| Small for gestational age | ||||||||||||||

| No | 80,106 | 92.3 | 92.2 | 92.5 | 92.6 | 92.8 | 92.8 | 79,496 | 92.7 | 92.5 | 92.6 | 92.7 | 92.6 | 92.6 |

| Yes | 6,495 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 6,339 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| Infant sex | ||||||||||||||

| Boys | 44,592 | 51.1 | 51.0 | 51.0 | 51.4 | 51.6 | 51.6 | 44,161 | 51.1 | 51.1 | 50.9 | 50.9 | 52.4 | 50.9 |

| Girls | 42,510 | 48.9 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 48.6 | 48.5 | 48.4 | 42,194 | 48.9 | 48.9 | 49.1 | 49.1 | 47.6 | 49.1 |

aSubgroup totals do not equal the overall number because of missing data.

Maternal sleep and preterm birth

Sleep duration and bedtime before and during pregnancy were not associated with preterm birth in this study (Table 2). However, very light sleep and very bad feeling when waking up during pregnancy were associated with late preterm birth in a multivariable model (RR for very light sleep vs. normal = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.04–1.35; RR for very bad feeling vs. normal = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.02–1.67) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Association between sleep during preconception and preterm birth in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (2011–2014).

| No. of participants | Preterm births | Maternal age-adjusted model | Multivariable modela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||||

| Preterm birth | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 6,028 | 288 | 4.8 | 1.08 | 0.95 | 1.22 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 1.17 |

| 6–7 | 17,260 | 820 | 4.8 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.18 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 1.15 |

| 7–8 | 29,350 | 1,283 | 4.4 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 21,521 | 922 | 4.3 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.09 |

| 9–10 | 8,830 | 353 | 4.0 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.04 |

| > 10 | 4,117 | 177 | 4.3 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.22 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 1.16 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 58,425 | 2,582 | 4.4 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 26,187 | 1,157 | 4.4 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.08 |

| Other | 2,494 | 104 | 4.2 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 1.19 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 1.11 |

| Late preterm birth (34–36 weeks) | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 5,973 | 233 | 3.9 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 1.26 | 1.07 | 0.93 | 1.22 |

| 6–7 | 17,104 | 664 | 3.9 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 1.21 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.19 |

| 7–8 | 29,091 | 1,024 | 3.5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 21,352 | 753 | 3.5 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.12 |

| 9–10 | 8,758 | 281 | 3.2 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 1.06 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 1.05 |

| > 10 | 4,080 | 140 | 3.4 | 1.03 | 0.86 | 1.22 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 1.17 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 57,925 | 2,082 | 3.6 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 25,962 | 932 | 3.6 | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.10 | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.10 |

| Other | 2,471 | 81 | 3.3 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.19 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 1.11 |

| Early preterm birth (23–33 weeks) | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 5,795 | 55 | 1.0 | 1.02 | 0.76 | 1.36 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 1.22 |

| 6–7 | 16,596 | 156 | 0.9 | 1.02 | 0.83 | 1.24 | 0.96 | 0.78 | 1.17 |

| 7–8 | 28,326 | 259 | 0.9 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 20,768 | 169 | 0.8 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 1.13 |

| 9–10 | 8,549 | 72 | 0.8 | 0.95 | 0.73 | 1.23 | 0.97 | 0.74 | 1.26 |

| > 10 | 3,977 | 37 | 0.9 | 1.10 | 0.78 | 1.55 | 1.05 | 0.73 | 1.49 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 56,343 | 500 | 0.9 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 25,255 | 225 | 0.9 | 1.03 | 0.88 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 1.14 |

| Other | 2,413 | 23 | 1.0 | 1.15 | 0.75 | 1.75 | 1.01 | 0.66 | 1.54 |

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

aAdjusted for maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index, parity, current history of diabetes or gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and intrauterine infection, history of preterm birth, and infertility treatment.

Table 3.

Association between sleep during pregnancy and late preterm birth in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (2011–2014).

| No. of participants | Preterm births | Maternal age-adjusted model | Multivariable modela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Sleep duration (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 4,305 | 169 | 3.9 | 1.11 | 0.94 | 1.30 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 1.28 |

| 6–7 | 12,948 | 469 | 3.6 | 1.02 | 0.92 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.12 |

| 7–8 | 26,769 | 944 | 3.5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 24,491 | 882 | 3.6 | 1.03 | 0.94 | 1.12 | 1.04 | 0.95 | 1.14 |

| 9–10 | 12,166 | 417 | 3.4 | 0.99 | 0.88 | 1.11 | 0.99 | 0.88 | 1.11 |

| > 10 | 5,679 | 196 | 3.5 | 1.03 | 0.89 | 1.20 | 1.01 | 0.87 | 1.18 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 63,212 | 2,298 | 3.6 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 21,173 | 717 | 3.4 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.03 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.03 |

| Other | 1,973 | 62 | 3.1 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 1.14 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 1.10 |

| Depth of sleep | |||||||||

| Very light | 6,135 | 266 | 4.3 | 1.21 | 1.06 | 1.38 | 1.19 | 1.04 | 1.35 |

| Light | 36,158 | 1,293 | 3.6 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 1.09 |

| Normal | 34,339 | 1,213 | 3.5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Deep | 8,035 | 258 | 3.2 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 1.07 |

| Very deep | 1,545 | 42 | 2.7 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 1.06 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 1.02 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Feeling when waking up in the morning | |||||||||

| Very bad | 1,372 | 65 | 4.7 | 1.38 | 1.08 | 1.75 | 1.31 | 1.02 | 1.67 |

| Bad | 17,875 | 629 | 3.5 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.10 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.10 |

| Normal | 53,523 | 1,890 | 3.5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Good | 11,868 | 428 | 3.6 | 1.02 | 0.92 | 1.13 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.16 |

| Very good | 1,526 | 60 | 3.9 | 1.11 | 0.86 | 1.42 | 1.08 | 0.83 | 1.39 |

| p for trend = 0.62b | p for trend = 0.94b | ||||||||

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

aAdjusted for maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index, parity, current history of diabetes or gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and intrauterine infection, history of preterm birth, and infertility treatment.

bLinear trend in the association was tested by assignment of ordinal variables for the five categories.

Maternal sleep and infant sleep

Sleep duration and bed time before pregnancy were not associated with ≥ 5 nocturnal awakenings. However, both sleep duration and bed time were likely to be related with an infant’s tendency to sleep longer during the day than at night (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between sleep before pregnancy and neonatal sleep in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (2011–2014).

| No. of participants | Outcome | Maternal age-adjusted model | Multivariable modela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||||

| Five or more awakenings during the night | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 5,455 | 355 | 6.5 | 1.02 | 0.91 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 0.96 | 1.20 |

| 6–7 | 15,797 | 924 | 5.9 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.02 |

| 7–8 | 27,051 | 1,733 | 6.4 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 19,855 | 1,316 | 6.6 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.07 |

| 9–10 | 8,116 | 538 | 6.6 | 1.05 | 0.96 | 1.16 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 1.09 |

| > 10 | 3,683 | 225 | 6.1 | 1.03 | 0.90 | 1.17 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.13 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 53,841 | 3,488 | 6.5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 23,870 | 1,450 | 6.1 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.12 |

| Other | 2,246 | 153 | 6.8 | 1.13 | 0.96 | 1.32 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 1.37 |

| Sleeping longer during the day than at night | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| 6 | 5,439 | 1,287 | 23.7 | 1.24 | 1.17 | 1.31 | 1.18 | 1.12 | 1.25 |

| 6–7 | 15,734 | 3,401 | 21.6 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.18 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.15 |

| 7–8 | 26,996 | 5,141 | 19.0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 19,811 | 3,535 | 17.8 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.02 |

| 9–10 | 8,088 | 1,349 | 16.7 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 1.00 |

| > 10 | 3,673 | 663 | 18.1 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 1.02 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 53,708 | 9,479 | 17,7 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 23,796 | 5,411 | 22.7 | 1.28 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.20 |

| Other | 2,237 | 486 | 21.7 | 1.20 | 1.11 | 1.30 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 1.22 |

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

aAdjusted for maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational age at birth, parity, infertility treatment, infant sex, small for gestational age, type of delivery, and postpartum depressive symptoms.

In the M-T2, waking up ≥ 5 times during the night was associated with maternal light sleep and feeling bad at awakening during pregnancy. Sleeping longer during the day than at night was related not only to maternal short sleep duration but also to late bed time and feeling bad at awakening (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between sleep during pregnancy and neonatal sleep in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (2011–2014).

| No. of participants | No. of outcome | Maternal age adjusted model | Multivariable modela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | |||||

| Five or more awakenings during the night | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 3,932 | 245 | 6.2 | 1.03 | 0.90 | 1.17 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 1.22 |

| 6–7 | 11,999 | 764 | 6.4 | 1.04 | 0.96 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.16 |

| 7–8 | 24,914 | 1,524 | 6.1 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 22,802 | 1,442 | 6.3 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.07 |

| 9–10 | 11,320 | 801 | 7.1 | 1.17 | 1.08 | 1.27 | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.20 |

| > 10 | 5,183 | 324 | 6.3 | 1.08 | 0.96 | 1.22 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.20 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 58,817 | 3,788 | 6.4 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 19,541 | 1,179 | 6.0 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.11 |

| Other | 1,792 | 133 | 7.4 | 1.19 | 1.01 | 1.41 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 1.41 |

| Depth of sleep | |||||||||

| Very light | 5,567 | 436 | 7.8 | 1.29 | 1.17 | 1.43 | 1.27 | 1.14 | 1.40 |

| Light | 33,580 | 2,224 | 6.6 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.14 |

| Normal | 31,909 | 1,929 | 6.1 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Deep | 7,510 | 418 | 5.6 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 1.02 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.04 |

| Very deep | 1,450 | 84 | 5.8 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 1.24 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Feeling when waking up in the morning | |||||||||

| Very bad | 1,240 | 112 | 9.0 | 1.52 | 1.27 | 1.81 | 1.53 | 1.28 | 1.84 |

| Bad | 16,514 | 1,131 | 6.9 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.20 |

| Normal | 49,715 | 3,073 | 6.2 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Good | 11,085 | 689 | 6.2 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.09 |

| Very good | 1,422 | 81 | 5.7 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 1.14 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 1.17 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Sleeping longer during the day than at night | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 3,914 | 915 | 23.4 | 1.19 | 1.12 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.09 | 1.24 |

| 6–7 | 11,958 | 2,663 | 22.3 | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.16 |

| 7–8 | 24,868 | 4,843 | 19.5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 22,738 | 4,147 | 18.2 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.01 |

| 9–10 | 11,288 | 1,898 | 16.8 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.97 |

| > 10 | 5,167 | 964 | 18.7 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 1.03 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 58,673 | 10,533 | 18.0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 19,499 | 4,516 | 23.2 | 1.28 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.22 |

| Other | 1,783 | 381 | 21.4 | 1.17 | 1.07 | 1.29 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 1.26 |

| Depth of sleep | |||||||||

| Very light | 5,550 | 1,162 | 20.9 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 1.15 |

| Light | 33,500 | 6,397 | 19.1 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.03 |

| Normal | 31,812 | 6,139 | 19.3 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Deep | 7,489 | 1,427 | 19.1 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.02 |

| Very deep | 1,448 | 286 | 19.8 | 1.02 | 0.91 | 1.13 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 1.10 |

| p for trend = 0.15b | p for trend = 0.02b | ||||||||

| Feeling when waking up in the morning | |||||||||

| Very bad | 1,237 | 300 | 24.1 | 1.24 | 1.12 | 1.37 | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.34 |

| Bad | 16,468 | 3,329 | 20.1 | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.07 |

| Normal | 49,582 | 9,472 | 19.0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Good | 11,056 | 2,094 | 18.9 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 |

| Very good | 1,416 | 258 | 18.1 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.05 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

aAdjusted for maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational age at birth, parity, infertility treatment, infant sex, small for gestational age, type of delivery, and postpartum depressive symptoms.

bLinear trend in the association was tested by assignment of ordinal variables for the five categories.

In the subanalysis of participants who slept 7–9 h before pregnancy, maternal short sleep and bed time after midnight were associated with longer day sleeps. Similarly, in the group of participants who slept 7–9 h during pregnancy, maternal short sleep before pregnancy was associated with more awakenings during the night and longer day-time sleep durations (Table S1).

Maternal sleep and infant temperament

In the M-T1, sleeping < 7 h and going to bed after midnight were associated with infants with bad mood, frequent crying for long periods, and intense crying (Table 6).

Table 6.

Association between sleep during preconception and neonatal irritability in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (2011–2014).

| No. of participants | Outcome | Maternal age-adjusted model | Multivariable modela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||||

| Bad mood | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 5,603 | 469 | 8.4 | 1.33 | 1.21 | 1.47 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.23 |

| 6–7 | 16,142 | 1,278 | 7.9 | 1.26 | 1.17 | 1.35 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.16 |

| 7–8 | 27,584 | 1,735 | 6.3 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 20,238 | 966 | 4.8 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 1.05 |

| 9–10 | 8,308 | 356 | 4.3 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.17 |

| > 10 | 3,804 | 239 | 6.3 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 1.17 | 1.02 | 1.33 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 54,935 | 2,803 | 5.1 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 24,434 | 2,084 | 8.5 | 1.68 | 1.59 | 1.77 | 1.12 | 1.06 | 1.19 |

| Other | 2,310 | 156 | 6.8 | 1.35 | 1.15 | 1.57 | 1.10 | 0.94 | 1.29 |

| Frequent crying, for long periods | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 5,587 | 1,255 | 22.5 | 1.28 | 1.21 | 1.35 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.24 |

| 6–7 | 16,093 | 3,332 | 20.7 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.23 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.13 |

| 7–8 | 27,534 | 4,810 | 17.5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 20,205 | 3,013 | 14.9 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.02 |

| 9–10 | 8,299 | 1,066 | 12.8 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.97 |

| > 10 | 3,800 | 619 | 16.3 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 1.09 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 54,840 | 8,530 | 15.6 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 24,365 | 5,178 | 21.3 | 1.38 | 1.33 | 1.42 | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.13 |

| Other | 2,313 | 387 | 16.7 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.06 |

| Intense crying | |||||||||

| Sleep time (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 5,592 | 1,448 | 25.9 | 1.30 | 1.23 | 1.36 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.20 |

| 6–7 | 16,114 | 3,886 | 24.1 | 1.21 | 1.17 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.12 |

| 7–8 | 27,546 | 5,490 | 19.9 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 20,201 | 3,234 | 16.0 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 1.01 |

| 9–10 | 8,295 | 1,149 | 13.9 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 1.00 |

| > 10 | 3,800 | 671 | 17.7 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.06 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 54,833 | 9,350 | 17.1 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 24,402 | 6,082 | 24.9 | 1.46 | 1.42 | 1.51 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.10 |

| Other | 2,313 | 446 | 19.3 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.24 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.05 |

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

aAdjusted for maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational age at birth, parity, infertility treatment, infant sex, small for gestational age, type of delivery, and postpartum depressive symptoms.

In the M-T2, we observed a relationship between bad mood and maternal short sleep, late bed time, light sleep, and feeling bad on awakening. Frequent crying for long periods was likely to be associated with short sleep, late bed time, light sleep, and feeling bad on awakening. Intense crying was also related to short sleep, late bed time, light sleep, and feeling bad on awakening (Table 7).

Table 7.

Association between sleep during pregnancy and neonatal temperament in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (2011–2014).

| No. of participants | Outcome | Maternal age-adjusted model | Multivariable modela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||||

| Bad mood | |||||||||

| Sleep duration (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 4,049 | 373 | 9.2 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.56 | 1.22 | 1.09 | 1.36 |

| 6–7 | 12,252 | 959 | 7.8 | 1.19 | 1.10 | 1.29 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.15 |

| 7–8 | 25,432 | 1,671 | 6.6 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 23,266 | 1,215 | 5.2 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.04 |

| 9–10 | 11,551 | 560 | 4.9 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 1.03 | 0.94 | 1.13 |

| > 10 | 5,343 | 301 | 5.6 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 1.07 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 60,030 | 3,214 | 5.4 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 20,013 | 1,759 | 8.8 | 1.64 | 1.55 | 1.74 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.22 |

| Other | 1,850 | 106 | 5.7 | 1.08 | 0.89 | 1.30 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 1.16 |

| Depth of sleep | |||||||||

| Very light | 5,740 | 480 | 8.4 | 1.47 | 1.33 | 1.61 | 1.46 | 1.32 | 1.61 |

| Light | 34,277 | 2,172 | 6.3 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 1.21 |

| Normal | 32,606 | 1,861 | 5.7 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Deep | 7,656 | 447 | 5.8 | 1.02 | 0.92 | 1.13 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.05 |

| Very deep | 1,475 | 107 | 7.3 | 1.27 | 1.05 | 1.53 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 1.45 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Feeling when waking up in the morning | |||||||||

| Very bad | 1,269 | 131 | 10.3 | 1.82 | 1.54 | 2.15 | 1.57 | 1.33 | 1.86 |

| Bad | 16,920 | 1,353 | 8.0 | 1.41 | 1.32 | 1.50 | 1.29 | 1.21 | 1.37 |

| Normal | 50,810 | 2,886 | 5.7 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Good | 11,265 | 612 | 5.4 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 1.01 |

| Very good | 1,448 | 83 | 5.7 | 1.01 | 0.82 | 1.25 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 1.22 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Frequent crying, for long periods | |||||||||

| Sleep duration (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 4,036 | 898 | 22.3 | 1.24 | 1.16 | 1.32 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.22 |

| 6–7 | 12,229 | 2,587 | 21.2 | 1.18 | 1.13 | 1.23 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.14 |

| 7–8 | 25,373 | 4,543 | 17.9 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 23,209 | 3,609 | 15.6 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 1.00 |

| 9–10 | 11,551 | 1,669 | 14.5 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 1.02 |

| > 10 | 5,333 | 862 | 16.2 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.04 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 59,915 | 9,559 | 16.0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 19,970 | 4,253 | 21.3 | 1.34 | 1.30 | 1.39 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 1.13 |

| Other | 1,846 | 356 | 19.3 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.34 | 1.15 | 1.04 | 1.26 |

| Depth of sleep | |||||||||

| Very light | 5,727 | 1,194 | 20.9 | 1.27 | 1.20 | 1.35 | 1.24 | 1.18 | 1.31 |

| Light | 34,222 | 6,148 | 18.0 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.14 |

| Normal | 32,529 | 5,294 | 16.3 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Deep | 7,642 | 1,270 | 16.6 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.04 |

| Very deep | 1,474 | 238 | 16.2 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 1.07 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Feeling when waking up in the morning | |||||||||

| Very bad | 1,262 | 301 | 23.9 | 1.44 | 1.30 | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.41 |

| Bad | 16,880 | 3,515 | 20.8 | 1.25 | 1.21 | 1.30 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.21 |

| Normal | 50,721 | 8,456 | 16.7 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Good | 11,243 | 1,668 | 14.8 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.92 |

| Very good | 1,446 | 191 | 13.2 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.89 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Intense crying | |||||||||

| Sleep duration (h) | |||||||||

| < 6 | 4,043 | 1,053 | 26.1 | 1.25 | 1.18 | 1.33 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.21 |

| 6–7 | 12,226 | 2,958 | 24.2 | 1.17 | 1.12 | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 1.11 |

| 7–8 | 25,404 | 5,256 | 20.7 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 8–9 | 23,224 | 3,941 | 17.0 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| 9–10 | 11,542 | 1,807 | 15.7 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.02 |

| > 10 | 5,327 | 946 | 17.8 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

| Bedtime | |||||||||

| 21:00–24:00 | 59,939 | 10,555 | 17.6 | ||||||

| 24:00–03:00 | 19,982 | 5,025 | 25.2 | 1.43 | 1.39 | 1.47 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.12 |

| Other | 1,845 | 381 | 20.7 | 1.17 | 1.07 | 1.29 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.19 |

| Depth of sleep | |||||||||

| Very light | 5,746 | 1,206 | 21.0 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.18 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.17 |

| Light | 34,306 | 6,813 | 19.9 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.12 |

| Normal | 32,669 | 6,129 | 18.8 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Deep | 7,664 | 1,545 | 20.2 | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.07 |

| Very deep | 1,481 | 294 | 19.9 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.11 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

| Feeling when waking up in the morning | |||||||||

| Very bad | 1,266 | 302 | 23.9 | 1.28 | 1.16 | 1.42 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 1.28 |

| Bad | 16,887 | 3,853 | 22.8 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.19 |

| Normal | 50,737 | 9,417 | 18.6 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Good | 11,251 | 2,093 | 18.6 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.02 |

| Very good | 1,445 | 255 | 17.7 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.04 |

| p for trend < 0.01b | p for trend < 0.01b | ||||||||

CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

aAdjusted for maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational age at birth, parity, infertility treatment, infant sex, small for gestational age, type of delivery, and postpartum depressive symptoms.

bLinear trend in the association was tested by assignment of ordinal variables for the five categories.

In the subanalysis of participants who slept 7–9 h before pregnancy, maternal short sleep during pregnancy was associated with bad mood in infants. Similarly, in the group of participants who slept 7–9 h during pregnancy, maternal late bed time before pregnancy was associated with bad mood in infants (Table S2).

Discussion

This study investigated whether maternal sleep before and during pregnancy was associated with preterm birth, infants sleep and temperament at 1 month of age, using data from a nationwide large-scale cohort study.

In this study, preterm birth was only associated with the quality of maternal sleep during pregnancy. Previous studies reported an association between preterm birth and subjective maternal sleep quality9,20. Subjective sleep depth and mood on awakening may reflect maternal SDB or depression21,22, both of which are known to increase preterm birth rates6,20. Interventions to improve sleep depth and mood on awakening could reduce preterm birth rates.

Contrary to a previous meta-analysis in 20185, we found no association of sleep duration with preterm birth. One conceivable reason for this difference is the lower rate of preterm birth in Japan compared to other countries23,24.

This study also revealed an association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with infant sleep and temperament at 1 month of age. To our knowledge, no studies have previously reported similar findings. However, infant sleep disorders and temperament have been reported to increase maternal stress25 and relate to maternal anxiety disorder and depression26. As a result, it may lead to parenting abandonment and child abuse27. If maternal sleep before and during pregnancy could be addressed to improve infant sleep and temperament, maternal postpartum mental disease and child abuse could also be reduced.

Maternal sleep before pregnancy also seemed to be associated with some features of infant temperament and frequent night awakenings in the group of participants with adequate sleep duration (7–9 h) during pregnancy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization recently issued statements on the importance of preconception care28, without emphasising maternal sleep. We should probably pay more attention to maternal sleep not only during pregnancy but also before pregnancy.

This study had four major limitations. First, maternal obesity and depression may be confounding factors: both are associated with sleeping problems and can cause maternal inflammation29,30. Some epidemiological studies have also reported that maternal obesity and depression are associated with preterm birth and developmental disorders20,31. In this study, we showed an association between maternal sleep and preterm birth, infant sleeping problems, and temperament after adjustment for pre-pregnancy BMI and postpartum depressive symptoms. Maternal sleep may affect these outcomes. However, adjustment for maternal depression could be insufficient because depressive symptoms were investigated postpartum.

Second, information about maternal and infant sleeping problems and infant temperament were collected using a questionnaire.

Third, because of the observational study design, we were not able to demonstrate how maternal sleep affected outcomes. Evidence suggests that inflammatory response plays a role, due to maternal sleep disruption during pregnancy causing preterm birth and aberrant development of offspring; short maternal sleep duration and SDB increases inflammatory cytokine levels9,10. It is believed that maternal inflammation can cause preterm birth11,12 and developmental disorders, such as ASD13,14. However, this study did not analyse inflammatory markers.

Fourth, the large sample size might show a statistically significant difference even when the difference is small. Since there have been no similar reports to this work, further investigations of relationships between maternal sleep and offspring’s outcome are necessary.

In conclusion, maternal sleep problems before and during pregnancy were associated with preterm birth and infant sleep problems and temperament.

Methods

Research ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ministry of Environment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological Studies and by the Ethics Committee of all participating institutions: the National Institute for Environmental Studies that leads the JECS, the National Center for Child Health and Development, Hokkaido University, Sapporo Medical University, Asahikawa Medical College, Japanese Red Cross Hokkaido College of Nursing, Tohoku University, Fukushima Medical University, Chiba University, Yokohama City University, University of Yamanashi, Shinshu University, University of Toyama, Nagoya City University, Kyoto University, Doshisha University, Osaka University, Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Hyogo College of Medicine, Tottori University, Kochi University, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kyushu University, Kumamoto University, University of Miyazaki, and University of Ryukyu.. Written informed consent, which also included the follow-up study of children after birth, was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with approved guidelines.

Study participants

Data used in this study were obtained from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS), an ongoing large-scale cohort study. The JECS elucidated environmental factors that affected children’s health and development and was designed to follow-up pregnant women until their newborns grow up to 13 years old. The participants were recruited between 2011 and 2014 in 15 regions throughout Japan, and the follow-up is carried out mainly by a self-administered questionnaire. The detailed protocol has been reported elsewhere32. The baseline profile of participants in the JECS was reported previously33. Participants answered a questionnaire about lifestyle and behaviour twice during pregnancy: at recruitment (early pregnancy, M-T1) and later during mid- and late-pregnancy (M-T2). Participants also answered a questionnaire about their newborns at 1 month after delivery (M-1m).

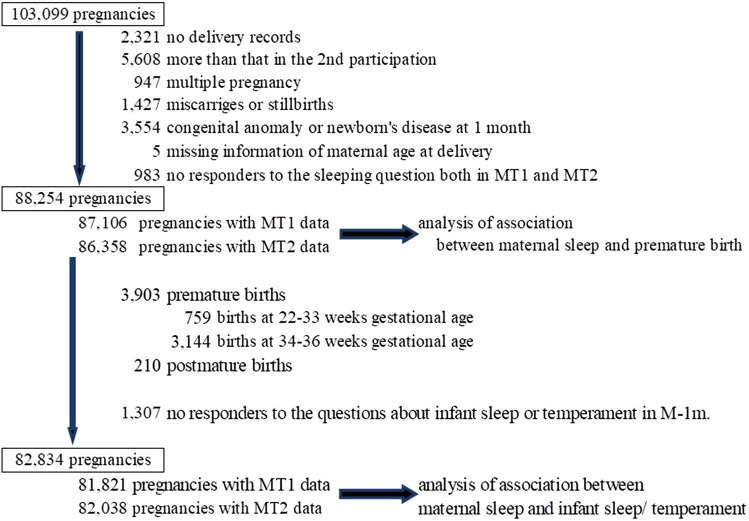

Of all 103,099 pregnancies, we excluded 14,845 pregnancies due to the following reasons: no delivery records (n = 2,321), prior participation in the study (n = 5,608), multiple pregnancy (n = 947), miscarriage or stillbirth (n = 1,427), congenital anomaly identified by 1 month old (n = 3,554), missing information on maternal age at delivery (n = 5), and no response to the questions related to sleep at both M-T1 and M-T2 (n = 983). The remaining 88,254 participants (87,106 with M-T1 data and 86,358 with M-T2 data) were included in the analysis of the association between maternal sleep and preterm birth. Then, we further excluded preterm or post-term deliveries (n = 4,113) and participants who did not respond to the questions related to the children’s sleep and temperament at M-1m (n = 1,307). (Fig. 1) Finally, 81,821 participants with M-T1 data and 82,038 participants with M-T2 data were included in the analysis of the association between maternal sleep and infant sleep and temperament.

Figure 1.

Flow chart representing the study population. M-T1: questionnaire administered at recruitment; M-T2: questionnaire administered during mid- and late-pregnancy; M-1m: questionnaire administered at 1 month after delivery.

Maternal sleep

In the M-T1 questionnaire, participants were asked about their sleep duration and bed time before pregnancy. We divided participants into six groups by sleep time: < 6 h, 6–7 h, 7–8 h, 8–9 h, 9–10 h, and > 10 h. Participants were also divided by bedtime: 9:00 p.m. to midnight, midnight to 3 a.m., and others.

In the M-T2 questionnaire, participants were asked about their sleep duration and bed time during pregnancy. The participants were divided into groups as described above for the M-T1. In addition, the M-T2 questionnaire included two more questions about sleep quality. One was, “How would you rate your average depth of sleep during the past month?” The other one was, “How would you rate your overall feeling when waking up in the morning during past month?” The answers to both questions were scored 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, representing very light (bad), relatively light (bad), normal, relatively deep (good), and very deep (good), respectively.

Preterm birth

Information on gestational age at delivery was transferred from medical records. Preterm birth was defined as birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation. In the present study, 3,903 (4.4%) pregnant women had preterm births. We divided these women into two groups: the early preterm birth group (birth before 34 completed weeks of gestation) and the late preterm birth group (birth after 34 gestational weeks). There were 759 (0.9%) women in the early preterm birth group and 3,144 (3.6%) women in the late preterm birth group. In the analysis of association between maternal sleep during pregnancy and preterm birth, we selected only late preterm birth as an outcome because some participants in the early preterm birth group did not answer M-T2 questionnaire between 22 and 28 weeks gestational age. So, the available number of participants in the early preterm group was too small to analyse.

Outcome (infant sleep and temperament)

At 1 month after delivery, we assessed infant sleep and temperature using a parents-reported questionnaire (M-1m questionnaire). For infant sleep, participants were asked about sleep and wake times during a 24-h period for their newborns. In this analysis, we focused on two points. First, we analysed the number of nocturnal awakenings. We defined ≥ 5 awakenings as too many because a previous study reported that the average number of awakenings during the night (20:00 – 7:59) is 2.95 (range: 1.0–5.0) for 2-week-old infants34. Second, we analysed whether the infants slept longer during the day (08:00–19:59) or at night (20:00–7:59). We regarded longer sleeping times during the day than at night as unusual.

Also, the M-1m questionnaire included three questions about infant temperament. The first question was, “When you hold your baby, how often do you feel difficulty to hold your baby due to his/her fretting, crying, or throwing his/her head back?”; the answer options were “often,” “sometimes”, “seldom,” and “none.” Those who answered “often” were categorised as “bad mood.” The second question was, “How often and for how long does your baby cry?”; the answer options were “quite often and for long periods,” “sometimes and for short periods,” and “seldom and almost never.” Those who answered as “quite often and long” were categorised as “frequent crying, for long periods.” The third question was “Does your baby cry very hard sometimes no matter what you do to stop him/her?”; the answer options were “yes” and “no,” and those who answered “yes” were categorised as “intense crying”. These categories are the same as those in our previous study35.

Covariates

Information about maternal age at delivery, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), parity, current history of diabetes, gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorder in pregnancy and intrauterine infection, history of preterm birth, gestational age at birth, infertility treatment, infant sex, type of delivery, small for gestational age and postpartum depressive symptoms were collected via self-administered questionnaires and/or medical records. Postpartum depressive symptoms were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), including in the questionnaire at 1 month after delivery36. According to previous studies37, participants with a score of 9 or more were categorized as having depressive symptoms.

Statistical analyses

We used the Poisson regression model with a robust error variance38 to explore the association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with each outcome and to estimate the relative risks (RRs) of each outcome and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We initially adjusted for maternal age at delivery, and then further adjusted as follows. In the analysis of the association between maternal sleep and preterm birth, we adjusted for smoking habits (never-smokers, ex-smokers who quit before pregnancy, smokers during early pregnancy), alcohol consumption (never-drinkers, ex-drinkers who quit before pregnancy, drinkers during early pregnancy), pre-pregnancy BMI (< 18·5, 18·5–24·9, ≥ 25·0 kg m2), current history of diabetes or gestational diabetes (yes, no), hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (yes, no) and intrauterine infection (yes, no), parity (0, ≥ 1), history of preterm birth (yes, no) and infertility treatment (yes, no).

In the analysis of the association between maternal sleep and infant sleep or temperament, we adjusted for smoking habits, alcohol consumption, pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational age at birth (37, 38, 39, 40, and 41 weeks of gestation), infant sex (boys, girls), parity, infertility treatment, type of delivery (vaginal, caesarean section), small for gestational age infants (yes, no), and postpartum depressive symptoms (yes, no).

We performed a subanalysis of infant sleep or temperament in the participant groups that reported adequate sleep durations of 7–9 h both at M-T1 and M-T2 to evaluate how maternal sleep before and during pregnancy impacts the outcome of these parameters.

The dataset used for statistical analyses was the jecs-ag-20160424 dataset, which was released in June 2016, and revised in October 2016, along with the supplementary dataset jecs-ag-20160424-sp1. Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for all analyses.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants in this study and all the individuals involved in data collection. The Japan Environment and Children's Study was funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Ministry of the Environment.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: S.M. Statistical analyses: T.M. Drafting of the manuscript and approval of the final content: K.N., S.M. and T.M. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Manuscript review: all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The Study Group members are listed at the end of this article.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Kazushige Nakahara and Takehiro Michikawa.

Contributor Information

Seiichi Morokuma, Email: morokuma@med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

The Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group:

Michihiro Kamijima, Shin Yamazaki, Yukihiro Ohya, Reiko Kishi, Nobuo Yaegashi, Koichi Hashimoto, Chisato Mori, Shuichi Ito, Zentaro Yamagata, Hidekuni Inadera, Takeo Nakayama, Hiroyasu Iso, Masayuki Shima, Youichi Kurozawa, Narufumi Suganuma, and Takahiko Katoh

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-67852-3.

References

- 1.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Special focus: measuring leisure in OECD countries 19. https://www.oecd.org/berlin/42675407.pdf (2009).

- 2.Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. Survey on time use and leisure activities in 2016: summary of results (QuestionnaireA) time use. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/shakai/2016/pdf/timeuse-a2016.pdf (2016).

- 3.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Vital Statistics of Japan 2017. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/dl/81-1a2en.pdf (2017).

- 4.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. Number of students taking special classes in 2014 (in Japanese). https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/tokubetu/material/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2015/03/27/1356210.pdf (2015)

- 5.Warland J, Dorrian J, Morrison JL, O’Brien LM. Maternal sleep during pregnancy and poor fetal outcomes: a scoping review of the literature with meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018;41:197–219. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown NT, Turner JM, Kumar S. The intrapartum and perinatal risks of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;219(2):147–161.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassan H, et al. The effect of maternal sleep-disordered breathing on the infant’s neurodevelopment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;212(5):656.e1–656.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Hons B, Cistulli PA, Hons M. Childhood health and educational outcomes associated with maternal sleep apnea: a population record-linkage study. Sleep. 2017;40(11):zsx158. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair LM, Porter K, Leblebicioglu B, Christian LM. Poor sleep quality and associated inflammation predict preterm birth: heightened risk among African Americans. Sleep. 2015;38(8):1259–1267. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okun ML, Luther JF, Wisniewski SR, Wisner KL. Disturbed sleep and inflammatory cytokines in depressed and nondepressed pregnant women. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(7):670–681. doi: 10.1097/psy.0b013e31829cc3e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappelletti M, Della Bella S, Ferrazzi E, Divanovic S, Mavilio D. Inflammation and preterm birth. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015;99(1):67–78. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3mr0615-272rr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwak-Kim J, Dambaeva S, Beaman K, Gilman-Sachs A, Salazar Garcia MD, Hussein Y. Inflammation induced preterm labor and birth. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018;129:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2018.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schobel SA, et al. Maternal immune activation and abnormal brain development across CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014;10(11):643–660. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estes ML, McAllister AK. Maternal immune activation: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science. 2016;353(6301):772–777. doi: 10.1126/science.aag3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart FM, Freeman DJ, Ramsay JE. Longitudinal assessment of maternal endothelial function and markers of inflammation and placental function throughout pregnancy in lean and obese mothers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:969–975. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christian LM, Porter K. Longitudinal changes in serum proinflammatory markers across pregnancy and postpartum: effects of maternal body mass index. Cytokine. 2014;70:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDade TW, Borja JB, Largado F, Adair LS, Kuzawa CW. Adiposity and chronic inflammation in young women predict inflammation during normal pregnancy in the Philippines. J. Nutr. 2016;146(2):353–357. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.224279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karmel BZ, et al. Early medical and behavioral characteristics of NICU infants later classified with ASD. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):457–467. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saenz J, Yaugher A, Alexander GM. Sleep in infancy predicts gender specific social-emotional problems in toddlers. Front. Pediatr. 2015;3:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fped.2015.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straub H, Adams M, Kim JJ, Silver RK. Antenatal depressive symptoms increase the likelihood of preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;207(4):329.e1–329.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pamidi S, Kimoff RJ. Maternal sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2018;153(4):1052–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chong Y-S, et al. Associations between poor subjective prenatal sleep quality and postnatal depression and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;202:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blencowe H, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2162–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purisch SE, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Epidemiology of preterm birth. Semin. Perinatol. 2017;41(7):387–391. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moe V, von Soest T, Fredriksen E, Olafsen KS, Smith L. The multiple determinants of maternal parenting stress 12 months after birth: The contribution of antenatal attachment style, adverse childhood experiences, and infant temperament. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1987. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Britton JR. Infant temperament and maternal anxiety and depressed mood in the early postpartum period. Women Health. 2011;51(1):55–71. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.540741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zahra ED, et al. Maternal child abuse and its association with maternal anxiety in the socio-cultural context of Iran. Oman Med. J. 2013;28(6):404–409. doi: 10.5001/omj.2013.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Preconception care policy brief (1). 1–8. doi:10.1016/S1002-0721(09)60023-5 (2013).

- 29.Huang E, et al. Maternal prenatal depression predicts infant negative affect via maternal inflammatory cytokine levels. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018;73:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Burg JW, Sen S, Chomitz VR, Seidell JC, Leviton A, Dammann O. The role of systemic inflammation linking maternal BMI to neurodevelopment in children. Pediatr. Res. 2016;79(1):3–12. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu S. Maternal obesity and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2362–2370. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawamoto T, et al. Rationale and study design of the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS) BMC Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michikawa T, et al. Baseline profile of participants in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS) J. Epidemiol. 2018;28(2):99–104. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20170018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Figueiredo B, Dias CC, Pinto TM, Field T. Infant sleep-wake behaviors at two weeks, three and six months. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2016;44:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morokuma S, et al. Non-reassuring foetal status and neonatal irritability in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study: a cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):15853. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34231-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamashita H, Yoshida K. Screening and intervention for depressive mothers of new-born infants. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2003;105(9):1129–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guangyong Z. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.