Abstract

Protein C is a natural anticoagulant activated by thrombin in a reaction accelerated by the cofactor thrombomodulin. The zymogen to protease conversion of protein C involves removal of a short activation peptide that, relative to the analogous sequence present in other vitamin K-dependent proteins, contains a disproportionately high number of acidic residues. Through a combination of bioinformatic, mutagenesis and kinetic approaches we demonstrate that the peculiar clustering of acidic residues increases the intrinsic disorder propensity of the activation peptide and adversely affects the rate of activation. Charge neutralization of the acidic residues in the activation peptide through Ala mutagenesis results in a mutant activated by thrombin significantly faster than wild type. Importantly, the mutant is also activated effectively by other coagulation factors, suggesting that the acidic cluster serves a protective role against unwanted proteolysis by endogenous proteases. We have also identified an important H-bond between residues T176 and Y226 that is critical to transduce the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ and the stimulatory effect of thrombomodulin on the rate of zymogen activation. These findings offer new insights on the role of the activation peptide in the function of protein C.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Biochemistry, Biophysical chemistry, Enzyme mechanisms, Enzymes, Proteins, Proteolysis

Introduction

The clotting enzyme thrombin performs procoagulant, prothrombotic and pro-inflammatory roles in the blood that are mediated by cleavage of fibrinogen and PAR11. In addition, and somewhat paradoxically, thrombin functions as a potent inhibitor of coagulation by activating the zymogen protein C and producing an enzyme itself endowed with diverse physiological roles as a natural anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory factor2. Cleavage of protein C by thrombin alone is extremely inefficient and requires the intervention of the endothelial cofactor thrombomodulin that boosts the kcat/Km for the interaction > 1,000-fold, mainly by enhancing kcat3. Importantly, the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex has exclusive activity toward protein C and no appreciable activity toward fibrinogen and PAR1 due to occupancy of exosite I by the soluble EGF domains of thrombomodulin4. Activated protein C inactivates cofactors Va and VIIIa with the assistance of protein S, down regulates the amplification and progression of the coagulation cascade and maintains patency of the capillaries5,6. As an anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective agent, activated protein C signals through PAR1 and PAR3 in ways that differ completely from thrombin’s activation mechanism and reduces cellular damage following ischemia/reperfusion of the brain, heart, lungs and kidneys, as well as sepsis7.

The protein C pathway is highly relevant to human pathophysiology5. For example, deficiency of protein C is linked to often fatal neonatal purpura fulminans8 and mild deficiency9 or mutations that compromise activation of protein C10 cause venous thromboembolism. On the other hand, abnormally low levels of activated protein C are associated with life threatening conditions such as atherosclerosis, stroke, sepsis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation11–14.

The mechanism of protein C activation has intrigued investigators for decades but remains incompletely understood. Why is cleavage of protein C by thrombin so inefficient in the absence of thrombomodulin? This property is at odds with thrombin being one of the most proficient proteases of the trypsin family, capable of cleaving fibrinogen and PAR1 at rates that are almost diffusion limited1,15. How does thrombomodulin achieve its cofactor effect? Is the effect on thrombin, protein C or both? Previous studies have supported paradigms emphasizing the action of thrombomodulin on thrombin4,16–23. For example, removal of potential electrostatic clash between acidic residues in the activation domain of protein C and negatively charged regions on the thrombin surface has been invoked as an important component of the thrombomodulin effect17,24. This proposal is difficult to reconcile with a number of observations: increasing the ionic strength of the solution does not oppose but actually favors protein C activation by thrombin25; the structure of thrombin bound to a fragment of the activation peptide of protein C documents no clash between D167 at the P3 position of protein C and negatively charged residues around the active site of the enzyme25; the same observation is reported by the structure of thrombin bound to a fragment of PAR1 that also bears an acidic residue at the P3 position and yet is the most specific physiological substrate of thrombin26. The claim that thrombomodulin causes large conformational changes in thrombin17–19,24,27 remains controversial4, 21,23,28,29. Under physiological conditions, thrombin is mostly bound to Na+ and in a rigid conformation according to recent NMR30and rapid kinetics22studies, thus leaving little room for large conformational transitions. Available structures of thrombin bound to fragment EGF456 of thrombomodulin4,23 are practically identical to the free, physiologically dominant E form of the enzyme22,31,32. Although these structures have been crystalized with peptidyl inhibitors bound in the catalytic cleft, which may have precluded detection of any conformational changes induced by thrombomodulin binding, there is no evidence of such changes from the analysis of the hydrolysis of small substrates21,33. Other studies have supported a more realistic scenario where the conformation of protein C plays an important role in the activation mechanism. The effect of thrombomodulin is mimicked at least in part by mutations of thrombin24,34–36 but also of protein C37,38. Ca2+ binding to the protease domain of protein C inhibits activation in the absence of thrombomodulin, but stimulates the same reaction in the presence of cofactor39–41. Even more compelling is the fact that thrombomodulin enhances the rate of diffusion (kon) of protein C within the active site of thrombin29, a parameter that depends on properties of the enzyme and substrate.

Two recent significant developments in the field have renewed interest in the mechanism of protein C activation. The active site Ser has been studied for years for its role in catalysis42,43, but has recently emerged as a major transducer of allosteric effects in the trypsin fold44. The role of S195 is manifested through subtle rearrangements of the OH group, without the need for large conformational transitions of the entire active site. Likewise, the Arg residue at the site of cleavage has been considered for years a passive component of zymogen activation42,45,46, especially of enzyme cascades47,48, but its constitutive exposure to solvent necessary for proteolytic attack has been questioned49. Specifically, mutagenesis experiments indicate that several acidic residues (i.e., D167, D172) around the scissile bond interact with R169 at the site of activation and partially protect it against proteolytic cleavage by thrombin25,39,50,51. Binding of thrombomodulin is believed to induce conformational changes around the site of activation in protein C that improve accessibility of R169 for effective proteolytic attack25. An intriguing new paradigm has emerged for cofactor-assisted interactions between trypsin-like zymogens and proteases that is directly relevant to the mechanism of protein C activation. The cofactor optimizes the orientation of the active site Ser of the enzyme and exposes the Arg residue in the activation domain of substrate.

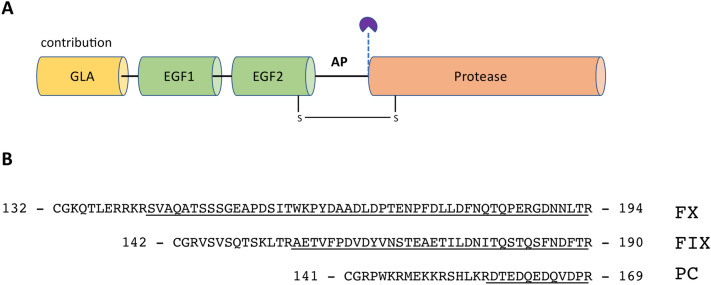

Protein C shares an identical modular domain assembly (Fig. 1A) with factor VII, factor IX, and factor X including a γ-carboxyglutamate (GLA) domain responsible for interaction with membrane surfaces, two epidermal growth factor (EGF1 and EGF2) domains that primarily serve as spacers and a protease domain which hosts the active site16,52–59. With the exception of factor VII, all of the foregoing zymogens contain an activation peptide between the EGF2 and protease domains54,55,57. Proteolytic removal of the activation peptide during zymogen activation triggers structural changes in the protease domain that are responsible for organization of the active site16. Interestingly, this region contains a peculiar clustering of acidic amino acids that creates a strong negative environment around the site of activation. In fact, half of all amino acids in the activation peptide of protein C have acidic side chains, localized in close proximity to the scissile bond R169-L170 that is cleaved by thrombin during zymogen activation. Because of the short length of the activation peptide, the acidic cluster of amino acids is also proximal to a cluster of basic residues located in a linker that connects the activation peptide with the EGF2 domain. Overall, the peculiar clustering of acidic and basic residues creates a strong dipolar environment around the activation peptide region which prompted us to evaluate its propensity for intrinsic disorder and to characterize the contribution of charged residues toward the activation rate of protein C.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the modular domain assembly of protein C (PC) with the site of thrombin cleavage (dashed line) located in the activation peptide (AP). Identical domain assemblies also characterize the structural architecture of closely related vitamin K-dependent proteins such as factor VII (FVII), factor IX (FIX), and factor X (FX). (B) The activation peptides of human FX, FIX, and PC. Shown is the sequence that stretches from the scissile bond Arg to the conserved Cys that forms a disulfide link between the EGF2 and protease domains. Underlined are the residues that comprise the activation peptide, while the remaining ones are located in the predominantly basic linker that connects the activation peptide with the EGF2 domain.

Results

Intrinsic disorder propensities

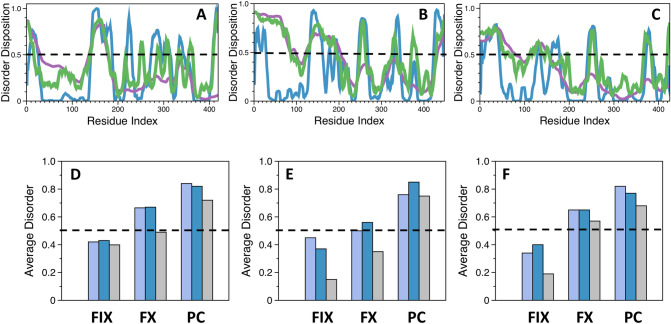

Figure 1B lists the amino acid sequences that constitute the activation peptide segment of different human vitamin-K dependent proteins. Significant differences in length, charge distribution and glycosylation exist among these segments, implicating an evolutionary divergence from a common ancestor enzyme. Among the three zymogens, protein C has the shortest activation peptide with only 12 amino acids, while those of factor IX (35 residues) and factor X (52 residues) are significantly longer. The activation peptide segments of factor IX and factor X are also glycosylated60–62 and, at least in factor X, the sugar moieties have an adverse effect on the rate of activation63and are responsible for extending the zymogen’s half-life in the circulation64–66. No glycosylation sites exist in the activation peptide of protein C, but this region features a disproportionately high number of charged residues. Indeed, 55% of all amino acids in the sequence comprising the activation peptide and the basic linker that connects it to the EGF2 domain have either acidic or basic side chains. The total number of charged residues in the analogous segment of factor X and factor IX corresponds to 30% and 22%, respectively. The peculiar localization of charges in protein C is often found in intrinsically disordered regions67, which prompted us to evaluate the disorder propensity of the amino acid sequence. For these analyses, we used three algorithms from the PONDR family of programs. Amongst these, the VSL2 algorithm68is one of the most accurate stand-alone disorder predictors, VLXT69 has high sensitivity to local sequence peculiarities and is often used for identifying disorder-based interaction sites, and VL370 provides accurate evaluation of long disordered regions. A score > 0.5 predicts that a given residue is localized in part of the sequence that tends to be disordered, while the opposite holds true for scores < 0.5. Analysis of the sequence of human protein C predicts that the longest and most disordered region stretches from residues 140 to 180 (Fig. 2A). This region contains the extended sequence around the scissile bond that is cleaved during zymogen activation and includes the basic linker, activation peptide and the 20-loop of the serine protease domain localized upstream of the site of activation. Other regions with notable propensity for disorder include the GLA domain and various loops that are part of the serine protease domain such as the flexible autolysis loop. In contrast, the EGF1 and EGF2 domains are relatively ordered. Extension of this approach to the sequence of human factor IX and factor X (Fig. 2B-C) shows that the activation peptide has the highest degree of disorder in protein C, followed by factor X and factor IX (Fig. 2D-F).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the intrinsic disorder propensity of the amino acid sequences of human (A) protein C (PC), (B) factor X (FX), and (C) factor IX (FIX) analyzed with the VLXT (blue), VL3 (purple) and VSL2 (green) algorithms from the PONDR family of programs. Average disorder scores for the sequences of the activation peptide (purple), the activation peptide and the basic linker that connects it to the EGF2 domain (blue), and the P12-P12′ residues (gray) obtained from analyses with the (D) VSL2, (E) VLXT, and (F) VL3 algorithms. Unprimed and primed numbers respectively denote amino acids located to the N- and C- termini of the scissile bond Arg at the P1 position. Scores were calculated from analysis of the entire amino acid sequence as described in Methods.

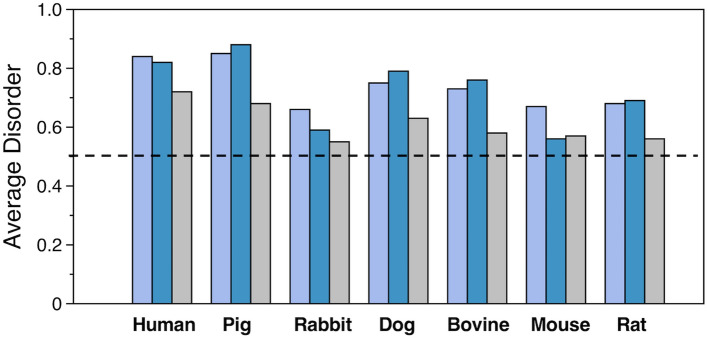

To better evaluate the evolutionary conservation of the disorder propensity in the activation peptide region, we constructed profiles of all mammalian amino acid sequences of protein C currently deposited in the UniProt database. After analyzing the entire sequence with the VSL2 algorithm, we calculated the average disorder score for the activation peptide with or without the basic linker that connects it to the EGF2 domain and the score for the sequence of the P12-P12′ residues (Fig. 3). Even though the activation peptide region in all protein C sequences tends to be disordered, we found moderate differences in their disorder disposition. The most pronounced level of disorder in the three regions of interest was observed in protein C from human and pig, while the lowest disorder propensity was found in the zymogen from rabbit, mouse and rat (Fig. 3). Because the binding of disordered regions is often accompanied by unfavorable entropic cost67, it remains to be determined whether mammalian sequences that have greater disorder disposition in their activation peptide region are activated by thrombin at a slower rate.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the intrinsic disorder propensity of various mammalian protein C amino acid sequences. Shown are the average disorder scores for the sequences of the activation peptide (purple), the activation peptide and the basic linker that connects it to the EGF2 domain (blue), and the P12-P12′ residues (gray). Scores were calculated from analysis of the entire amino acid sequence as described in Methods.

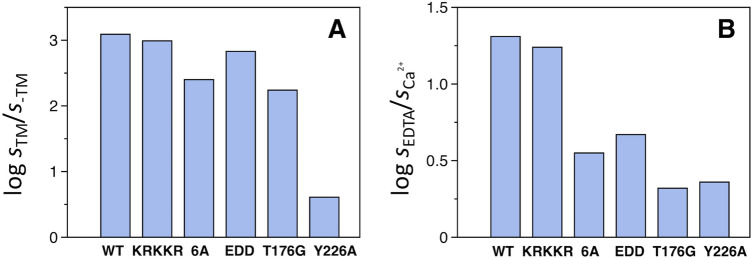

Activation of protein C mutants by thrombin

To understand how the clustering of acidic and basic residues in the activation peptide of protein C influences the rate of activation by thrombin, we expressed two mutants where the majority of charged residues were neutralized by Ala replacement. The 6A mutant (D158A/E160A/D161A/E163A/D164A/D167A) features all acidic amino acids replaced by Ala and the KRKKR mutant (K146A/R147A/K150A/K151A/R152A) has five basic amino acids replaced in the linker region. Residues K156 and R157 are part of the dipeptide that is proteolytically removed by a furin-like proprotein convertase71 during the secretion process and were left intact. Neutralization of the basic cluster of residues has no effect on the activation rate by thrombin under all conditions tested, i.e., with and without Ca2+ or thrombomodulin (Table 1). In contrast, substitution of the acidic residues in the 6A mutant enhanced the rate of activation 12-fold in the presence of Ca2+, but only marginally (twofold) in the absence of Ca2+ and in the presence of thrombomodulin (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Enhanced activation rates were also observed with the EDD mutant (E160A/D167A/D172A), which was characterized previously in the GLA-domainless form25. The results indicate that the acidic cluster contributes to the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ on activation of wild type protein C in the absence of thrombomodulin. It is possible that some of the acidic residues in the activation peptide assume a conformation that “cages” R169 in the scissile bond in the presence of Ca2+25, thereby restricting accessibility of this residue to thrombin. Alternatively, or in addition to the foregoing mechanism, neutralization of six acidic residues may reduce flexibility and disorder of the activation peptide and the entropic cost associated with the binding interaction with thrombin.

Table 1.

Values of kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) for the activation of wild-type and mutant protein C by thrombin

| − TM + CaCl2 |

+ TM + CaCl2 |

− TM + EDTA |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 220 ± 20 | 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| KRKKR | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 186 ± 2 | 3.3 ± 0.6 |

| 6A | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 550 ± 50 | 8.1 ± 0.9 |

| EDD | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1,590 ± 40 | 11 ± 1 |

| T176G | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 350 ± 30 | 4.2 ± 0.6 |

| Y226A | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.5 |

Experimental conditions: 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 145 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG8000 with 10 mM CaCl2 or 5 mM EDTA at 37 ºC. TM, Thrombomodulin

Figure 4.

Activation of protein C variants by thrombin. Shown are the values of s = kcat/Km measured (A) in the presence and absence of thrombomodulin (TM), and (B) in the presence of EDTA and CaCl2. Experimental conditions were: 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 145 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG 8,000 at 37 °C. The buffer used for the reactions shown in panel A was supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2.

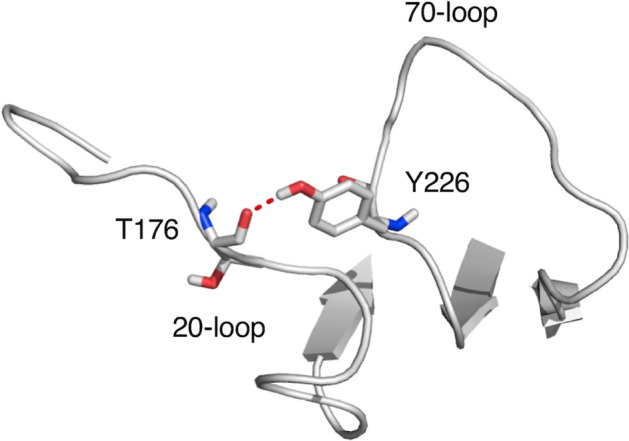

Several studies have shown that binding of Ca2+ and thrombomodulin affects the conformation of the activation peptide of protein C25,40,41. In the absence of a structure for protein C, it is unclear how these interactions are transduced allosterically to the region around the thrombin cleavage site at R169. The locale for Ca2+ binding is the 70-loop of the protease domain of protein C16,40,52. Thrombomodulin binds to residues located in the 30-, 60- and 70-loops72–75. These loops are numbered according to alignment of the protease domain of protein C with chymotrypsin and residues numbered according to this nomenclature are shown in parenthesis. The crystal structure of activated protein C16 shows the 70-loop in close proximity to the 20-loop close to the site of activation at R169 (R15) and a strong H-bond forms between the backbone O atom of T176 (T22) and the side chain of Y226 (Y71) (Fig. 5). The mutant Y226A drastically compromises the ability of thrombomodulin to enhance the rate of protein C activation by thrombin (Table 1 and Fig. 4). The 1,500-fold increase observed for wild type is reduced to only fourfold in the mutant. The Y226A mutation also alleviates the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ in the absence of thrombomodulin. In the wild type, Ca2+ inhibits the rate of activation 20-fold but in the mutant the effect is reduced to twofold (Table 1 and Fig. 4). We propose that the ineffective activation of the Y226A mutant by the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex primarily arises from perturbation of the H-bond with T176; future experiments with other Y226 variants (i.e., Y226F) should clarify how important the bulky benzyl ring is for the cofactor-dependent stimulation on the rate of activation.

Figure 5.

The H-bond between T176 and Y226 in the crystal structure of activated protein C16 connects the 20- and 70- loops of the protease domain. These residues correspond to T22 and Y71 in the chymotrypsin numbering. Image drawn with PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

The critical T176-Y226 interaction was also perturbed from the 20-loop side by introducing the T176G mutation. However, the T176G mutant has no effect on the thrombomodulin-mediated enhancement of protein C activation which remains as pronounced as in the wild type (Table 1 and Fig. 4). This is probably because Gly, just like any residue that is introduced at position 176, can still form an H-bond through its main chain O atom with the side chain of Y226 and preserve the structural connectivity between the 20- and 70-loops. On the other hand, the T176G mutation reduces the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ to about twofold relative to the rate measured in the presence of EDTA. Also, in the presence of Ca2+, the T176G variant is activated at a rate that is 11-fold faster than wild-type (Table 1 and Fig. 4). We propose that the alleviation of the Ca2+ inhibitory effect that is seen with the T176G mutant results from elimination of the rigid branched side chain which increases the flexibility of neighboring residues in the 20-loop. Branched side chains, such as that of Thr, are known to restrict the flexibility of the main chain torsion angles, while Gly, which lacks a side chain, has the opposite effect. Future mutagenesis experiments should clarify to what extent a branched side chain at position 176 is necessary in mediating the Ca2+ inhibitory effect through minimizing the conformational entropy of the 20-loop.

Activation by factor Xa

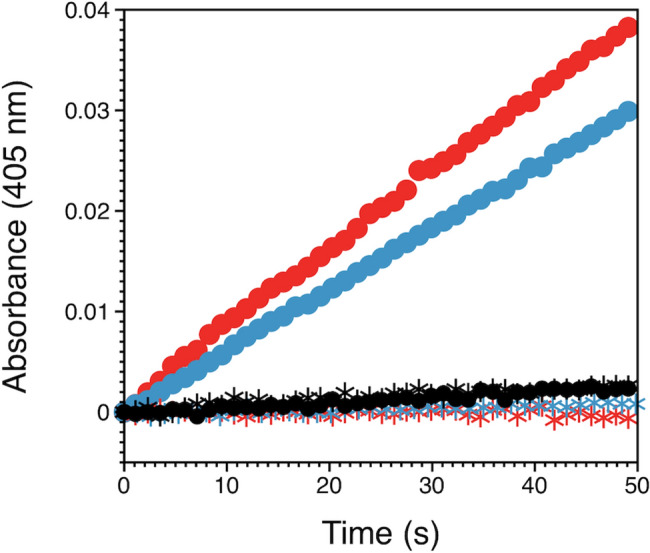

We have previously shown that a GLA-domainless protein C variant carrying the triple EDD mutation spontaneously autoactivates over a slow time scale25. The three acidic residues in protein C have a direct counterpart in the zymogen prethrombin-2 where they structurally “cage” R15. Once replaced to Ala, the site of activation at R15 is exposed to solvent and prethrombin-2 rapidly converts to thrombin by autoactivation49,76. Screening of the site of activation from solvent may be a general strategy for protection from unwanted proteolysis, especially among zymogens with modular assembly. In addition to prothrombin and protein C, plasminogen assumes a closed form stabilized by intramolecular interaction of the activation domain with kringles that keeps the zymogen in an activation-resistant conformation77. Binding of kringles to fibrin clots and cell-surface receptors induces a transition to an open form that can be cleaved and converted to plasmin by physiological activators. The activation peptide of factor X also appears to play a protective role against autoactivation. Rudolph et al.61 have reported that deletion of residues 137–183 from the activation peptide of factor X produces a mutant with increased propensity for intermolecular activation in the presence of membrane surfaces. Importantly, the mutant becomes susceptible to activation by thrombin61, contrary to what it is observed for wild type under physiological conditions. We therefore examined the possibility that perturbation of the acidic residues in the activation peptide of protein C could introduce specificity toward proteases other than the physiological activator thrombin. Indeed, the protein C mutant 6A is activated by factor Xa at a significant rate under conditions where wild type protein C is not (Fig. 6). A similar effect is also observed with the EDD mutant.

Figure 6.

Activation of protein C variants by factor Xa. Constructs were incubated with 50 nM factor Xa for 90 min and the reaction was quenched with excess apixaban. Formation of activated protein C wild type (black circles), mutant 6A (red circles) and mutant EDD (blue circles) was quantified by monitoring the absorbance at 405 nm that resulted from cleavage of the chromogenic substrate S-2366. The kcat/Km values for the FXa catalyzed activation of 6A and EDD are 1.4 ± 0.2 mM−1 s−1 and 0.57 ± 0.05 mM−1 s−1, respectively. Control experiments without addition of factor Xa to the reaction mixture are shown by asterisks for protein C wild type (black), mutant 6A (red) and mutant EDD (blue). Experimental conditions were: 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 145 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.1% PEG 8,000, 200 μM phospholipids, 250 nM hirudin at 37 °C.

Discussion

In the present study we have employed bioinformatic analyses to evaluate the disorder profiles of the vitamin K-dependent zymogens that share the same modular domain assembly as protein C and contain an activation peptide that is proteolytically removed during activation. The activation peptide of protein C is predicted to be intrinsically disordered (Fig. 2) and to an extent that is more pronounced than in zymogens like factors IX and X. The disorder arises from the large density of acidic residues within the short activation peptide. Replacement of these acidic residues produces a more ordered activation domain that is less sensitive to the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ and is also cleaved by factor Xa in addition to the physiological activator thrombin. Effects observed for factor X61 may have a similar molecular origin. Removal of residues in the activation domain of this zymogen introduces specificity toward thrombin and also a tendency to autoactivate, possibly through ordering of the domain. It is also notable that, unlike protein C, the activation peptides of factors IX and X60,61 are glycosylated and that this post-translational modification may be needed to protect the scissile bond from proteolysis from non-physiological activators.

The combined replacement of all basic residues in the linker that connects the activation peptide with the EGF2 domain in protein C has no significant effect on the rate of activation by thrombin. Some of the residues in this linker are known to have a moderate influence on the proteolytic processing of the K156-R157 dipeptide by a furin-like proprotein convertase71. A recent study has documented an important role for K150 and K151 in the anticoagulant and cytoprotective functions of activated protein C78. In contrast to the basic cluster, the 6A mutant carrying substitutions in six acidic residues in the activation domain features a reduction in the inhibitory effect of Ca2+ and a modest enhancement of the effect of thrombomodulin on the rate of thrombin activation. The results are consistent with previous studies where mutations of D167 and E160 in the activation peptide and D172 immediately downstream to the site of cleavage at R169 produced single, double and triple mutants activated more rapidly by thrombin25,39,50,51. While part of the rate-enhancing effect that ensues from these mutations might result from attenuating the level of electrostatic repulsion between protein C and negatively charged residues that rim the active site of thrombin79, we believe that the acidic residues in the activation peptide primarily protect protein C activation in the absence of thrombomodulin by hindering access to the scissile bond. The effect is similar to what has been reported for prethrombin-225,49. The relevant similarity between the two proteins in this region is demonstrated by the sequence 311ELLESYIDGRIVE323 in prethrombin-2 and 160EDQEDQVDPRLID172 in protein C25,49, where the acidic residues caging R320 or R169 in the scissile bond are in bold. An alternative explanation may also be provided by the reduced disorder in the activation domain caused by the 6A mutation. Interactions involving highly disordered regions are usually energetically unfavorable due to large entropy costs associated with formation of a productive complex67. The two effects, i.e., caging of R169 and disorder in the activation domain, are not mutually exclusive and may cooperate in reducing cleavage of protein C by thrombin in the absence of thrombomodulin. The acidic residues in the activation domain targeted in this study may also play an important role in preventing non-physiological activation. The 6A and EDD mutants are activated by factor Xa at a significant rate, unlike wild type (Fig. 6). The results echo similar observations with coagulation factor X, where deletion in the activation peptide results in constructs that can be activated by thrombin, unlike wild type, and are also capable of autoactivation as observed in coagulation FVII that lacks an activation peptide61.

The results reported here support the new paradigm recently emerged for protein C activation where thrombomodulin acts as a dual cofactor that utilizes two end-points for its allosteric effect, i.e., the catalytic Ser of thrombin44 and the Arg residue at the site of cleavage of protein C25. Other residues of thrombin and protein C obviously participate in the allosteric effect of thrombomodulin, as suggested by several groups24,29,34–38, but they do so by eventually altering these two end-points.

Methods

Evaluation of intrinsic disorder propensity

The following amino acid sequences were downloaded from the UniProt database with their respective UniProt IDs shown in brackets: human factor IX [P00740], human factor X [P00742], and protein C from human [P04070], rabbit [Q28661], bovine [P00745], dog [Q28278], pig [Q9GLP2], rat [P31394] and mouse [P33587]. Each amino acid sequence was evaluated for its propensity for intrinsic disorder with the VSL268, VLXT69 and VL370 algorithms from the PONDR family of predictors. In all cases, we only considered the sequences of the mature proteins starting from the first amino acid in the GLA domain. Where applicable, after evaluating the intrinsic disorder propensity of the entire amino acid sequence, we calculated the average disorder score for the sequences around the activation peptide as the ratio of the disorder score sum over the total number of residues.

PCR mutagenesis, protein expression and purification

Quick-change lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) was used to introduce the mutations described in the results sections into the human protein C plasmid carrying a C-terminal HPC-4 tag. Plasmids were transfected into baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche) according to a standard protocol supplied by the manufacturer. After incubation of 48 h, selection of stably expressing clones was initiated by incubating the transfected cells with 1 mg/mL geneticin and expression of stably selected clones was verified by western blotting using the HPC-4 antibody. Stably selected clones were gradually expanded and transferred into large cell factories. Protein C variants were initially purified by immunoaffinity chromatography using a resin that was coupled with the HPC-4 antibody as described for prethrombin 129. After the immunoaffinity chromatography step, the sample was diluted to achieve a final NaCl concentration below 50 mM and the protein was loaded onto a 1 mL Q-sepharose Fast-Flow (GE Healthcare) column attached through its top to a 1 mL HiTrap heparin column (GE healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA. Then the heparin column was detached and the protein was eluted from the Q-sepharose Fast-Flow column using a 0.05–1 M NaCl gradient. Lastly, the protein was purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a pre-packed superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5 and 145 mM NaCl.

Kinetic assays

Activation of protein C variants was monitored using a discontinuous assay under pseudo-first order conditions where the concentration of substrate was maintained below the Km value. Reactions initiated by thrombin (1–150 nM) were measured in the presence of 10 mM CaCl2 with or without rabbit thrombomodulin (50–200 nM) or in the presence of 5 mM EDTA. The factor Xa assays were conducted in the presence of 200 μM phospholipids (75% phosphatidylcholine and 25% phosphatidylserine) and included 250 nM hirudin in order to exclude any activity from possible contamination with thrombin. Reactions with thrombin were stopped at specific time intervals with excess hirudin, while those with factor Xa were quenched with the specific inhibitor apixaban (MedChemExpress). Formation of activated protein C at given time intervals was quantified from the cleavage of the chromogenic substrate S-2366 (Diapharma) by monitoring the absorbance at 405 nm. The kcat/Km value was obtained after fitting the initial velocities to an exponential equation. Assays were performed at least in duplicates with standard errors lower that 5%. All measurements were conducted under experimental conditions: 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 145 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG 8,000 at 37 °C. Thrombin was purified and activated as described previously29. Human factor Xa was purchased from Haematologic Technologies Inc.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Research Grants HL049413, HL139554 and HL147821.

Author contributions

B.M.S., L.A.P. and E.D.C. designed the research and analyzed the data; B.M.S. and L.A.P. performed the research; B.M.S. and E.D.C. wrote the manuscript. All Authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Recombinant reagents and data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Di Cera E. Thrombin. Mol. Aspects Med. 2008;29:203–254. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esmon CT. Inflammation and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:1343–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esmon NL, Owen WG, Esmon CT. Isolation of a membrane-bound cofactor for thrombin-catalyzed activation of protein C. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:859–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuentes-Prior P, et al. Structural basis for the anticoagulant activity of the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex. Nature. 2000;404:518–525. doi: 10.1038/35006683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esmon CT. The protein C pathway. Chest. 2003;124:26S–32S. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3_suppl.26s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann KG. Thrombin formation. Chest. 2003;124:4S–10S. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3_suppl.4s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, Mosnier LO. Activated protein C: biased for translation. Blood. 2015;125:2898–2907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-355974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branson HE, Katz J, Marble R, Griffin JH. Inherited protein C deficiency and coumarin-responsive chronic relapsing purpura fulminans in a newborn infant. Lancet. 1983;2:1165–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffin JH, Evatt B, Zimmerman TS, Kleiss AJ, Wideman C. Deficiency of protein C in congenital thrombotic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 1981;68:1370–1373. doi: 10.1172/JCI110385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitsma PH. Protein C deficiency: summary of the 1995 database update. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:157–159. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway EM. Thrombomodulin and its role in inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2012;34:107–125. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morser J. Thrombomodulin links coagulation to inflammation and immunity. Curr. Drug Targets. 2012;13:421–431. doi: 10.2174/138945012799424606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starr ME, et al. Increased coagulation and suppressed generation of activated protein C in aged mice during intra-abdominal sepsis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015;308:H83–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00289.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starr ME, et al. Age-dependent vulnerability to endotoxemia is associated with reduction of anticoagulant factors activated protein C and thrombomodulin. Blood. 2010;115:4886–4893. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Cera E. Thrombin as an anticoagulant. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2011;99:145–184. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385504-6.00004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mather T, et al. The 2.8 A crystal structure of Gla-domainless activated protein C. Embo J. 1996;15:6822–6831. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Locht A, et al. The thrombin E192Q-BPTI complex reveals gross structural rearrangements: implications for the interaction with antithrombin and thrombomodulin. Embo J. 1997;16:2977–2984. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye J, Esmon NL, Esmon CT, Johnson AE. The active site of thrombin is altered upon binding to thrombomodulin: two distinct structural changes are detected by fluorescence, but only one correlates with protein C activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:23016–23021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esmon CT, Mather T. Switching serine protease specificity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:933–937. doi: 10.1038/2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala YM, et al. Thermodynamic investigation of hirudin binding to the slow and fast forms of thrombin: evidence for folding transitions in the inhibitor and protease coupled to binding. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;253:787–798. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vindigni A, White CE, Komives EA, Di Cera E. Energetics of thrombin-thrombomodulin interaction. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6674–6681. doi: 10.1021/bi962766a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogt AD, Chakraborty P, Di Cera E. Kinetic dissection of the pre-existing conformational equilibrium in the trypsin fold. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:22435–22445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.675538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams TE, Li W, Huntington JA. Molecular basis of thrombomodulin activation of slow thrombin. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;7:1688–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Bonniec BF, Esmon CT. Glu-192—Gln substitution in thrombin mimics the catalytic switch induced by thrombomodulin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:7371–7375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pozzi N, Barranco-Medina S, Chen Z, Di Cera E. Exposure of R169 controls protein C activation and autoactivation. Blood. 2012;120:664–670. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-415323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gandhi PS, Chen Z, Di Cera E. Crystal structure of thrombin bound to the uncleaved extracellular fragment of PAR1. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:15393–15398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esmon CT. Thrombomodulin as a model of molecular mechanisms that modulate protease specificity and function at the vessel surface. FASEB J. 1995;9:946–955. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.10.7615164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayashi T, Zushi M, Yamamoto S, Suzuki K. Further localization of binding sites for thrombin and protein C in human thrombomodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:20156–20159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu H, Bush LA, Pineda AO, Caccia S, Di Cera E. Thrombomodulin changes the molecular surface of interaction and the rate of complex formation between thrombin and protein C. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:7956–7961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lechtenberg BC, Johnson DJ, Freund SM, Huntington JA. NMR resonance assignments of thrombin reveal the conformational and dynamic effects of ligation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14087–14092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005255107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niu W, et al. Crystallographic and kinetic evidence of allostery in a trypsin-like protease. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6301–6307. doi: 10.1021/bi200878c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pozzi N, Vogt AD, Gohara DW, Di Cera E. Conformational selection in trypsin-like proteases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012;22:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu LW, Vu TK, Esmon CT, Coughlin SR. The region of the thrombin receptor resembling hirudin binds to thrombin and alters enzyme specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:16977–16980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu QY, et al. Single amino acid substitutions dissociate fibrinogen-clotting and thrombomodulin-binding activities of human thrombin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:6775–6779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Bonniec BF, MacGillivray RT, Esmon CT. Thrombin Glu-39 restricts the P'3 specificity to nonacidic residues. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:13796–13803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezaie AR, Yang L. Thrombomodulin allosterically modulates the activity of the anticoagulant thrombin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12051–12056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135346100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang L, Manithody C, Rezaie AR. Activation of protein C by the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex: cooperative roles of Arg-35 of thrombin and Arg-67 of protein C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:879–884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507700103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grinnell BW, Gerlitz B, Berg DT. Identification of a region in protein C involved in thrombomodulin-stimulated activation by thrombin: potential repulsion at anion-binding site I in thrombin. Biochem. J. 1994;303(Pt 3):929–933. doi: 10.1042/bj3030929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rezaie AR, Esmon CT. The function of calcium in protein C activation by thrombin and the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex can be distinguished by mutational analysis of protein C derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:26104–26109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rezaie AR, Mather T, Sussman F, Esmon CT. Mutation of Glu-80–>Lys results in a protein C mutant that no longer requires Ca2+ for rapid activation by the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:3151–3154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang L, Prasad S, Di Cera E, Rezaie AR. The conformation of the activation peptide of protein C is influenced by Ca2+ and Na+ binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:38519–38524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perona JJ, Craik CS. Structural basis of substrate specificity in the serine proteases. Protein Sci. 1995;4:337–360. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter P, Wells JA. Dissecting the catalytic triad of a serine protease. Nature. 1988;332:564–568. doi: 10.1038/332564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelc LA, et al. Why Ser and not Thr brokers catalysis in the trypsin fold. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1457–1464. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hedstrom L. Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:4501–4524. doi: 10.1021/cr000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Page MJ, Di Cera E. Serine peptidases: classification, structure and function. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2008;65:1220–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7565-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krem MM, Di Cera E. Evolution of enzyme cascades from embryonic development to blood coagulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gros P, Milder FJ, Janssen BJ. Complement driven by conformational changes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nri2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pozzi N, et al. Crystal structures of prethrombin-2 reveal alternative conformations under identical solution conditions and the mechanism of zymogen activation. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10195–10202. doi: 10.1021/bi2015019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richardson MA, Gerlitz B, Grinnell BW. Enhancing protein C interaction with thrombin results in a clot-activated anticoagulant. Nature. 1992;360:261–264. doi: 10.1038/360261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richardson MA, Gerlitz B, Grinnell BW. Charge reversal at the P3' position in protein C optimally enhances thrombin affinity and activation rate. Protein Sci. 1994;3:711–712. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmidt AE, et al. Thermodynamic linkage between the S1 site, the Na+ site, and the Ca2+ site in the protease domain of human activated protein C (APC): sodium ion in the APC crystal structure is coordinated to four carbonyl groups from two separate loops. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:28987–28995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Banner DW, et al. The crystal structure of the complex of blood coagulation factor VIIa with soluble tissue factor. Nature. 1996;380:41–46. doi: 10.1038/380041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perera L, et al. Modeling zymogen protein C. Biophys. J. 2000;79:2925–2943. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76530-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perera L, Darden TA, Pedersen LG. Modeling human zymogen factor IX. Thromb. Haemost. 2001;85:596–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Perera L, Darden TA, Pedersen LG. Predicted solution structure of zymogen human coagulation FVII. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:35–47. doi: 10.1002/jcc.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venkateswarlu D, Perera L, Darden T, Pedersen LG. Structure and dynamics of zymogen human blood coagulation factor X. Biophys. J. 2002;82:1190–1206. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75476-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brandstetter H, Bauer M, Huber R, Lollar P, Bode W. X-ray structure of clotting factor IXa: active site and module structure related to Xase activity and hemophilia B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9796–9800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brandstetter H, et al. X-ray structure of active site-inhibited clotting factor Xa: implications for drug design and substrate recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:29988–29992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurachi K, Davie EW. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA coding for human factor IX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:6461–6464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.21.6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rudolph AE, Mullane MP, Porche-Sorbet R, Daust HA, Miletich JP. The role of the factor X activation peptide: a deletion mutagenesis approach. Thromb. Haemost. 2002;88:756–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agarwala KL, et al. Activation peptide of human factor IX has oligosaccharides O-glycosidically linked to threonine residues at 159 and 169. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5167–5171. doi: 10.1021/bi00183a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang L, Manithody C, Rezaie AR. Functional role of O-linked and N-linked glycosylation sites present on the activation peptide of factor X. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;7:1696–1702. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gueguen P, Cherel G, Badirou I, Denis CV, Christophe OD. Two residues in the activation peptide domain contribute to the half-life of factor X in vivo. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:1651–1653. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johansson L, Karpf DM, Hansen L, Pelzer H, Persson E. Activation peptides prolong the murine plasma half-life of human factor VII. Blood. 2011;117:3445–3452. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kurdi M, Cherel G, Lenting PJ, Denis CV, Christophe OD. Coagulation factor X interaction with macrophages through its N-glycans protects it from a rapid clearance. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e45111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Understanding protein non-folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:1231–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peng K, Radivojac P, Vucetic S, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z. Length-dependent prediction of protein intrinsic disorder. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7:208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Romero P, et al. Sequence complexity of disordered protein. Proteins. 2001;42:38–48. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010101)42:1<38::aid-prot50>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peng K, et al. Optimizing long intrinsic disorder predictors with protein evolutionary information. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2005;3:35–60. doi: 10.1142/s0219720005000886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Essalmani R, et al. Thrombin activation of protein C requires prior processing by a liver proprotein convertase. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:10564–10573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.770040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gale AJ, Griffin JH. Characterization of a thrombomodulin binding site on protein C and its comparison to an activated protein C binding site for factor Va. Proteins. 2004;54:433–441. doi: 10.1002/prot.10627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerlitz B, Grinnell BW. Mutation of protease domain residues Lys37-39 in human protein C inhibits activation by the thrombomodulin-thrombin complex without affecting activation by free thrombin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22285–22288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Knobe KE, et al. Probing the activation of protein C by the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex using structural analysis, site-directed mutagenesis, and computer modeling. Proteins. 1999;35:218–234. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990501)35:2<218::aid-prot8>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang L, Rezaie AR. The fourth epidermal growth factor-like domain of thrombomodulin interacts with the basic exosite of protein C. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:10484–10490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pozzi N, et al. Autoactivation of thrombin precursors. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:11601–11610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Law RH, et al. The X-ray crystal structure of full-length human plasminogen. Cell. Rep. 2012;1:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamashita, A., Zhang, Y., Sanner, M.F., Griffin, J.H. & Mosnier, L.O. C-terminal residues of activated protein C light chain contribute to its anticoagulant and cytoprotective activities. J. Thromb. Haemost. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Pozzi N, et al. Loop electrostatics asymmetry modulates the preexisting conformational equilibrium in thrombin. Biochemistry. 2016;55:3984–3994. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Recombinant reagents and data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.