Abstract

Cellular senescence is a major barricade on the path of cancer development, yet proteins secreted from senescent cells exert complex and often discordant effects on subsequent cancer evolution. Somatic genome alternations driving the formation of nevi and melanoma are efficient inducers of cellular senescence. Melanocyte and melanoma cell senescence is likely to come into play as a key factor affecting the course of tumorigenesis and responsiveness to therapy; little mechanistic information has been generated, however, that substantiates this idea and facilitates its clinical translation. Here, we established and characterized a model of melanoma cell senescence in which pharmacologically induced DNA damage triggered divergent ATM kinase- and STING-dependent intracellular signaling cascades and resulted in cell cycle arrest, cytomorphologic remodeling, and drastic secretome changes. Targeted proteome profiling revealed that senescent melanoma cells in this model secreted a panoply of proteins shaping the tumor immune microenvironment. CRISPR-mediated genetic ablation of the p38α and IKKβ signaling modules downstream of the ATM kinase severed the link between DNA damage and this secretory phenotype without restoring proliferative capacity. A similar genetic dissection showed that loss of STING signaling prevented type I interferon induction in DNA-damaged melanoma cells but otherwise left the senescence-associated processes in our model intact. Actionable proteins secreted from senescent melanoma cells or involved in senescence-associated intracellular signaling hold potential as markers for melanoma characterization and targets for melanoma treatment.

Keywords: melanoma, DNA damage, senescence, secretome, protein kinase

Introduction

Cells that have acquired oncogenic genome alterations are programmed to enter a state of irreversible cell cycle arrest, or senescence. DNA damage and chromosomal aberrations associated with high rates of DNA replication and mitotic dysregulation are thought to drive their senescence [1,2]. Cellular senescence can serve as an effective barrier to tumorigenesis, limiting the proliferative potential of cells on their path to malignancy. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) further contributes to restraining cancer development; among the proteins secreted from senescent cells are cytokines, chemokines, and other classes of signaling molecules crucial for the recruitment and activation of immune cells exerting an antitumor action [3–6]. Paradoxically, senescent cells also secrete proteins with immunosuppressive, angiogenic, and cytoprotective activities that render the tissue environment conducive to neoplastic growth and malignant progression [6–11]. Therefore, cellular senescence can either suppress or promote tumorigenesis, but little is known about the conditions that determine the net effect of cellular senescence on specific cases of cancer. This knowledge gap impedes the use of senescence-associated molecular events as diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets in clinical oncology.

Activating mutations in BRAF and NRAS, the most common mutations in melanoma [12], are also frequently detected in acquired and congenital melanocytic nevi [13,14]. Melanocytes expressing a constitutively active BRAF or NRAS variant set out to proliferate but are held in check and form stable nevi as they adopt a senescent phenotype [15,16]. Additional genome alterations and epigenetic reprogramming appear to enable precancerous melanocytes to escape this arrest and become malignant [17,18]. Even after overcoming oncogene-induced senescence during the early stage of cancer development, cells in established tumors are still prone to DNA damage and senescence that are attributable to their inherent genome instability and genotoxic stress. Exposure to genotoxic metabolites such as reactive oxygen species has been shown to drive melanoma cell senescence [19,20]. A senescent phenotype arising in established melanoma—even in a fraction of cells constituting the tumor mass—likely exerts profound effects on malignant progression and response to therapy. Melanoma is a type of cancer with high mutation burden and correspondingly high loads of neoantigens [21], features that correlate with tumor-associated immune effector activity [22] as well as with clinical response to immune checkpoint blockade [23,24]. The SASP presumably plays as a key factor in natural immune surveillance and therapy-induced immune responses against melanoma. The secretome of senescent melanoma cells, however, has not been thoroughly characterized. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms linking genomic damage to secretome changes in melanoma remain to be elucidated.

The DNA damage-responsive protein kinase ATM triggers the intracellular signaling cascade leading to the induction of the senescent phenotype [1,25–27]. Activation of ATM results in its autophosphorylation and the induction of p53 and γ-H2AX proteins [28–30]. p53 enforces cell cycle arrest through transcriptionally inducing the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 [31,32]. Molecular pathways distinct from the ATM-p53-p21 axis are thought to drive cytomorphologic alterations and secretome changes during cellular senescence [26,27]. The sensing of cytoplasmic micronuclei, a product of erroneous segregation of damaged chromosomes during mitosis, by cGAS and STING has been proposed as a key event linking genotoxic stress to the senescent phenotype including the SASP [33–35]. It remains to be clarified whether cGAS-STING signaling contributes to the senescent phenotype in general or in certain cell types or physiological contexts. cGAS-STING signaling has been shown to play a role in IRF3-driven interferon-β (IFN-β) induction in some but not all conditions promoting cellular senescence [35,36]. IFN-β produced in DNA-damaged cells has been shown to reinforce cellular senescence [36,37]. The proliferation-to-senescence transition is accompanied by changes in the abundance or activity of histone-modifying enzymes including KDM5A/JARID1A, MLL1, EZH2, and p300 [38–41]. Metabolic reprogramming also occurs during cellular senescence, as exemplified by an increase in lipid synthesis and cytoplasmic lipid droplet formation [42,43].

In this study, we devise an in vitro model of melanoma senescence in which drug-induced DNA double-strand breaks trigger a cascade of signaling events that culminates in cell cycle arrest and the SASP. Using this model, we demonstrate that senescent melanoma cells secrete a suite of proteins that function to shape the tumor immune microenvironment. We also find that SASP induction in melanoma cells depends on the protein kinases p38α and IKKβ, which relay signals from ATM to SASP-related gene transcription, but can occur independently of STING signaling. This study reveals novel intracellular signaling events associated with melanoma senescence and identifies actionable molecular targets for clinical translation.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

B16 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. A375, MM455, MM608, Hs944T, and Roth cells were gifts from Hensin Tsao and originally from the sources described previously [44]. These cell lines have been authenticated by DNA fingerprinting based on polymerase chain reaction amplification and DNA sequencing of specific loci.

Reagents

Doxorubicin (Dxr), gemcitabine, irinotecan, cyclophosphamide, dacarbazine, and BMS345541 were from Sigma-Aldrich; and KU55933 and SC409 from EMD Millipore. Antibodies against the following proteins were used in immunoblotting after 1:1000 dilution and in immunofluorescence staining after 1:50 to 1:1000 dilution: p-ATM (sc-47739), p53 (sc-6243), RNA Pol II (sc-899), BRG1 (sc-10768), p300 (sc-585), IκBα (sc-371), NF-κB RelA (sc-372), p38α (sc-535), and vinculin (sc-73614; all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology); γ-H2AX (2577), KDM5A (3876), EZH2 (5246), caspase-3 (9662), p-IRF3 (4947), p-p38 (9211), and STING (13647; all from Cell Signaling Technology); IKKα (IMG-136A) and IKKβ (IMG-129A; both from Imgenex); caspase-2 (MAB2507) and actin (A4700; both from Sigma-Aldrich); p21 (ab188224) and TGF-β1 (ab92486; both from Abcam); PLIN2 (NB110–40877; Novus Biologicals); and IRF3 (51–3200; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell culture and imaging

All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with high glucose supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%), penicillin (50 unit/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml; all from Thermo Fisher Scientific). To analyze clonogenic proliferation or gross cytomorphology, cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and visualized by bright-field microscopy. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity in cells was visualized using a β-galactosidase activity staining kit (Cell Signaling Technology). To detect micronuclei, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized with cold 0.5% Triton X-100, and incubated with Hoechst 33324. After treatment with the anti-fading agent VectaShield (Vector Laboratories), the signal was visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Cell viability was determined using an MTT assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Protein analysis

Whole cell lysates and subcellular protein fractions were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting as described [44]. Immunoblot signals were quantified with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). To prepare conditioned media, 106 cells were left untreated or treated with Dxr for 24 h, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline twice, and incubated in serum-free medium for additional 24 h, during which secreted proteins were collected. Proteins in conditioned media were analyzed by silver staining and subjected to quantitative proteome profiling using the Quantibody Multiplex ELISA platform (RayBiotech).

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the Trizol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subjected to cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Relative transcript abundance was determined by real-time quantitative PCR using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

CRISPR genome editing

CRISPR/Cas9 lentiviral vectors (GenScript) were based on pLentiCRISPR v2 and contained the following sgRNA target sequences: Mapk14 (mouse p38α gene), 5’-ggtagatgagaaactgaacg-3’; and Ikbkb (mouse IKKβ gene), 5’-gccctacctgattgtgccac-3’. To introduce indel mutations into Mapk14 and Ikbkb, B16 cells were infected with lentiviral particles generated from these vectors or transfected with the corresponding plasmids, respectively. Lentiviral particles were generated by 293T cell transfection and quantified using the QuickTiter Lentivirus Titer Kit (Cell Biolabs) and used in B16 cell infection in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml) for four hours. Lentivirus-infected or plasmid-transfected B16 cells were subjected to selection with puromycin (2 μg/ml) two days later to obtain p38α-knockout and IKKβ-knockout cells. STING-knockout B16 cells were previously described [45].

Histology and immunofluorescence

To obtain mouse tumors exposed to Dxr in vivo, 1 × 106 B16 cells were injected into the right hind legs of 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice as in a previous study [44]. After tumors grew to 100 mm3 in volume, mice were administered i.p. Dxr (1 mg/kg) on day 0, 2, 4, and 6. Tumors were harvested when they reached 2,000 mm3 in size (approximately on day 19–21). Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were sectioned and analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin staining or by immunofluorescence using marker-specific primary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488/594-conjugated secondary antibodies, and Hoechst 33324.

TCGA data analysis

TCGA data (clinical, RPPA, and mRNASeq) were downloaded from the GDAC Firehose, the Cancer Proteome Atlas Portal, and the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics. Survival analysis of patient groups with differential protein and mRNA abundances was performed using Prism software (GraphPad) and the OncoLnc web tool.

Statistical analysis

Data values are expressed as mean ± S.D. P values were obtained by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, and Cox regression analysis.

Results

DNA damage-induced senescence of B16 melanoma cells

We used B16 mouse melanoma cells to devise an in vitro model of melanoma senescence. B16 cells, having originated from a C57BL/6 mouse, can form tumors when engrafted in immune-competent mice with a C57BL/6 background. Findings from a B16 cell-based senescence model can therefore feed into a subsequent investigation of how melanoma senescence plays out in vivo—in particular how it interacts with host immunity. We sought to establish a method to induce B16 cell senescence that would permit biochemical detection and analysis of DNA damage-proximal signaling events and the SASP. To this end, we first tested several chemotherapeutic agents for their ability to activate ATM signaling in B16 cells. ATM autophosphorylation and the induction of p53 and γ-H2AX proteins occurred in B16 cells exposed to Dxr and, albeit less prominently, to gemcitabine (Fig. 1a). The other chemotherapeutic agents tested (irinotecan, cyclophosphamide, and dacarbazine) did not activate ATM signaling. Dxr induced a similar extent of ATM phosphorylation at concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 4 μg/ml, whereas the induction of p53 and p21 peaked at 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Dxr-induced intracellular signaling and senescence-associated phenotypic changes in B16 cells.

(a and b) Whole cell lysates from B16 cells left untreated (−) or treated with Dxr, irinotecan (Itc), gemcitabine (Gct), cyclophosphamide (Cph), and dacarbazine (Dcz) as indicated were analyzed by immunoblotting. p-, phosphorylated.

(c-e) B16 cells were left untreated or treated with Dxr (0.5 μg/ml; Dxr0.5), re-plated as indicate, and stained with crystal violet (c and d) or for SA-β-gal activity (e). SA-β-gal+ cell frequency was determined based on their numbers per image field (n = 3).

(f and g) B16 cells were treated with Dxr0.5 and analyzed by immunoblotting as in (a). Immunoblot signals were quantified by densitometry, and relative protein amounts (signal intensities of the indicated proteins relative to vinculin) are plotted (g).

We examined the ability of Dxr to induce B16 cell senescence. B16 cells exposed to 0.5 μg/ml of Dxr (Dxr0.5) for 24 hours remained viable and, when harvested and replated in Dxr-free medium, attached to the plate surface within 12 hours (Fig. 1c). They, however, ceased to proliferate and failed to form clonal cell aggregates in this secondary culture (Fig. 1c). Dxr0.5-treated cells also displayed an altered morphology with enlarged cell bodies and dense cytoplasmic granules typical of senescent cells (Fig. 1d) and stained for SA-β-gal activity (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. 1a, Supplemental Digital Content 1). This phenotypic shift was accompanied by changes in the abundance of proteins implicated in epigenetic reprogramming (p300, KDM5A, EZH2) and lipid dynamics (PLIN2, caspase-2) during cellular senescence (Fig. 1, f and g).

B16 cells exposed to Dxr in vivo also exhibited a molecular signature of cellular senescence. B16 tumors formed in C57BL/6 host mice were refractory to treatment with Dxr [44]. Upon Dxr administration, these tumors became more pigmented and induced p21 and the SASP component TGF-β1 (Supplementary Fig. 2, a–c; Supplemental Digital Content 1). TGF-β1 is known to reinforce the senescent phenotype and sustain p21 expression in senescent cells via paracrine action [46].

DNA damage-induced secretome changes in B16 melanoma cells

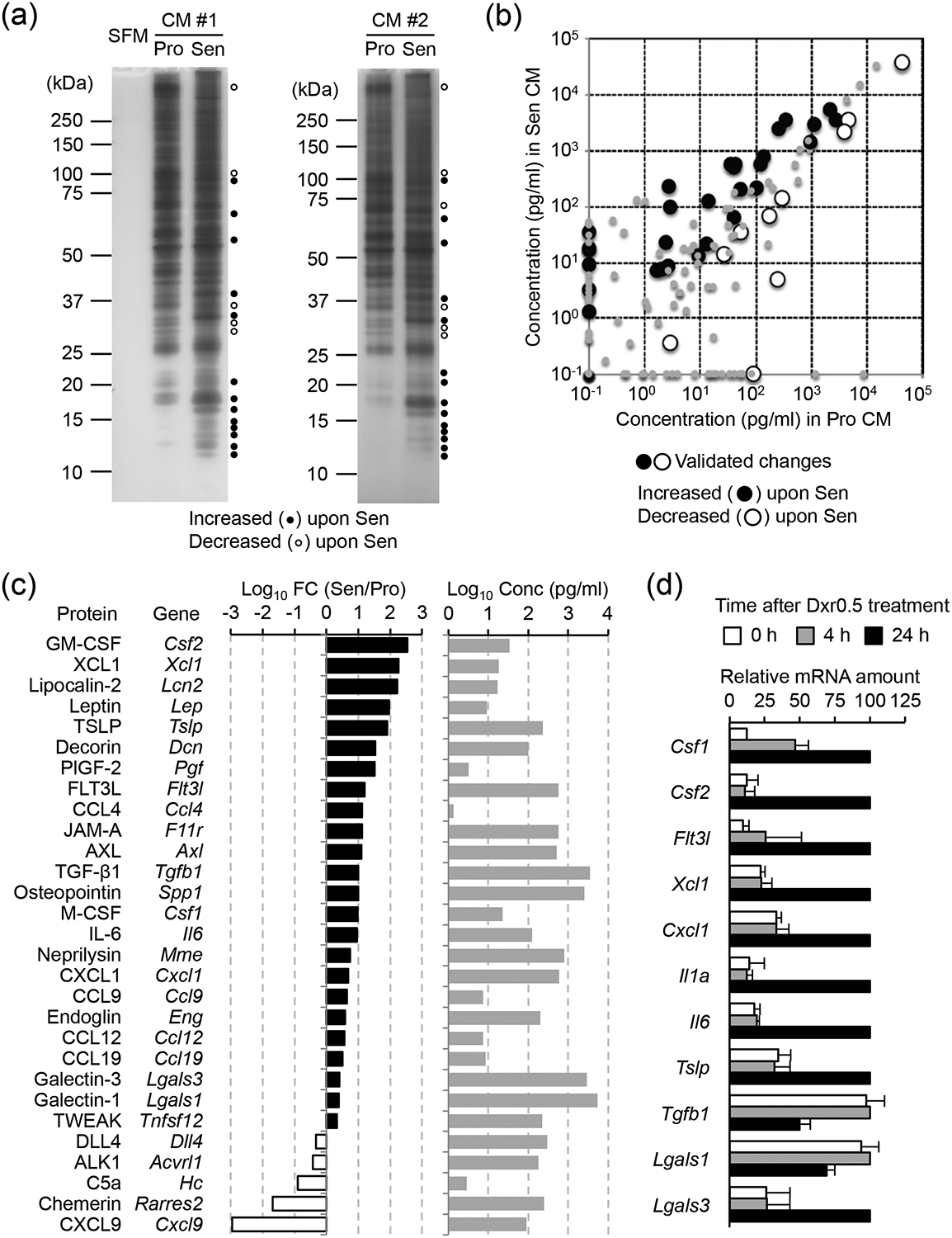

To determine whether Dxr0.5 treatment resulted in robust induction of the SASP in B16 cells, we compared the protein composition of conditioned media from proliferative B16 cells versus Dxr0.5-exposed B16 cells in a senescent state. Gel separation and silver staining of proteins contained in serum-free conditioned media revealed a net increase in protein secretion and a drastic change in secretome composition associated with B16 cell senescence (Fig. 2a). To analyze the secretion of specific proteins quantitatively, we performed targeted proteome profiling of the conditioned media using antibody microarrays (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1). The proteins secreted in greater amounts by senescent B16 cells included cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors targeting immune cells of various hematopoietic lineages and playing a role in antitumor immune surveillance or tumor immune evasion (Fig. 2c). Notable among the functional categories represented by these proteins were macrophage and dendritic cell (DC) development (M-CSF, GM-CSF, FLT3L), DC recruitment (XCL1, CCL9, CCL19), neutrophil/myeloid-derived suppressor cell recruitment (CXCL1), immune regulation (IL-6, TSLP, TWEAK, TGF-β1, AXL, lipocalin-2), tissue remodeling (PIGF-2), metabolic control (leptin), and cell-cell/cell-matrix interactions (galectin-1/3, decorin, JAM-A, osteopontin, endoglin). We observed Dxr0.5-responsive elevations in the mRNA of SASP components in B16 cells (Fig. 2d), suggesting that DNA damage-induced protein secretion resulted from increased expression of the genes encoding secreted proteins. TGF-β1 and galectin-1, encoded by Tgfb1 and Lgals1, respectively, were exceptions to this observation: their secretion from Dxr0.5-exposed cells occurred without an increase in their mRNA (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Dxr-induced secretome changes in B16 cells.

(a-c) B16 cells were left untreated or treated with Dxr (0.5 μg/ml) for 24 h, and then cultured in fresh serum-free (a) or serum-containing (b and c) medium for another 24 h. Conditioned medium (CM) from these cells, respectively, was subjected to SDS-PAGE and silver staining (a) or antibody microarray-based proteome profiling (b and c). The changes in protein amount validated in an independent experiment are denoted with black and white circles (b). SFM, serum-free medium; Pro, proliferative (untreated); Sen, senescent (Dxr-treated); FC, fold change.

(d) RNA from B16 cells treated as indicated was analyzed by qPCR (n = 2).

Signaling modules linking DNA damage to the SASP of B16 melanoma cells

In addition to triggering the ATM-p53-p21 cascade, Dxr-induced DNA damage has been shown to activate a multitude of stress-responsive protein kinase and transcription factor modules such as those involving p38, IκB kinase (IKK)/NF-κB, and IRF3 [47–49]. Dxr-exposed B16 cells exhibited signs of their activation—p38 phosphorylation, IκBα degradation (a consequence of phosphorylation by IKK and a prerequisite for NF-κB liberation and nuclear translocation), and IRF3 phosphorylation (Fig. 3a). We used the ATM kinase inhibitor KU55933 to determine which Dxr-triggered signaling events were downstream of and dependent on ATM. Pharmacological ATM inhibition not only attenuated p53 induction but also prevented p38 phosphorylation and NF-κB nuclear translocation in Dxr0.5-treated B16 cells (Fig. 3, b and c). p21 gene (Cdkn1a) induction in response to Dxr0.5 was also reduced by ATM inhibition (Fig. 3d). By contrast, Dxr0.5-induced IRF3 nuclear translocation and IFN-β gene (Ifnb1) induction were intact in the presence of the ATM kinase inhibitor (Fig. 3, c and d), showing their distinct signaling requirements. Of note, combined treatment with Dxr0.5 and the ATM kinase inhibitor, but not with either alone, caused B16 cell death in less than 12 hours, a period of time that preceded the manifestation of the senescent phenotype (Fig. 3e). This observation suggested a critical requirement for ATM in the survival of B16 cells after incurring DNA damage.

Fig. 3.

Role of ATM kinase activity in Dxr-induced intracellular signaling in B16 cells.

(a-c) Whole cell lysates (a and b) and cytoplasmic/nuclear extracts (c) from B16 cells treated as indicated were analyzed by immunoblotting. p-, phosphorylated; ATMi, ATM kinase inhibitor.

(d) RNA from B16 cells treated as indicated was analyzed by qPCR (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; NS, not significant (relative to DMSO, 4 h).

(e) B16 cells were treated as indicated and stained with crystal violet 24 h later.

To determine the role of p38 and IKK/NF-κB signaling in Dxr0.5-induced B16 cell senescence, we generated B16 cells with genetic ablation of p38α (the p38 isoform relevant to the DNA damage response) and IKKβ (the NF-κB-activating IKK subunit) by CRISPR genome editing. Loss of p38α and IKKβ did not preclude the deployment of the ATM-p53-p21 axis (Fig. 4, a–c) or the induction of IFN-β expression (Fig. 4c), cell cycle arrest (Fig. 4, d and e), and SA-β-gal activity (Fig. 4f; Supplementary Fig. 1b, Supplemental Digital Content 1) in Dxr0.5-treated B16 cells. The two protein kinases, however, were found to contribute substantially to shaping the secretome of cells after exposure to Dxr0.5: their deficiency led to altered patterns of protein secretion from senescent B16 cells, overall weakening the SASP (Fig. 5, a and b). Intriguingly, the amounts of secreted proteins from proliferative B16 cells, too, decreased in the absence of p38α and IKKβ, suggesting a role for their basal kinase activity or kinase-independent function in cells not exposed to Dxr. Antibody microarray analysis (Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1) revealed that p38α and IKKβ gene knockout abolished or reduced the senescence-associated secretion of overlapping but non-identical sets of proteins (Fig. 5c; Clusters II-IV). In addition, there were proteins whose secretion was not elicited by Dxr0.5 treatment in cells with intact expression of p38α and IKKβ but potently induced in p38α-deficient and IKK-β-deficient cells (Fig. 5c; Clusters V-VII). The secretion of some proteins remained unaffected by p38α and IKKβ deficiency (Fig. 5c; Cluster I). Notably, IKKβ gene ablation caused a global decrease in protein secretion under both proliferative and senescent conditions when analyzed by gel electrophoresis and silver staining (Fig. 5b), yet the antibody microarray-based protein profiling detected many proteins secreted from IKKβ-deficient B16 cells in magnitudes comparable to those of wild-type cells (Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1). This discrepancy may have resulted from different ranges of detection sensitivity of the two analytical approaches: silver staining can detect only highly abundant proteins and does not likely visualize sub-nanogram amounts of the majority of antibody microarray-identified proteins. The effects of p38α and IKKβ deficiency on the Dxr0.5-responsive increase in the mRNA of SASP components were largely consistent with those on their secretion (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 4.

Effects of p38α and IKKβ gene ablation on Dxr-induced intracellular signaling and senescence-associated phenotypic changes in B16 cells.

(a and b) Whole cell lysates from wild-type (WT) and gene-knockout (KO) B16 cells treated as indicated were analyzed by immunoblotting. p-, phosphorylated.

(c) RNA from WT and gene-KO B16 cells treated as indicated was analyzed by qPCR (n = 3). NS, not significant (relative to WT, 4 h).

(d-f) WT and gene-KO B16 cells were treated as indicated and stained with crystal violet (d and e) or for SA-β-gal activity (f) as in Fig. 1. Cell aggregates (colonies) per culture plate were counted (n = 3; e). SA-β-gal+ cell frequency was determined based on their numbers per image field (n = 3; f). **, P < 0.01 (relative to Untreated; e). NS, not significant (relative to WT, Dxr0.5; f).

Fig. 5.

Effects of p38α and IKKβ gene ablation on Dxr-induced secretome changes in B16 cells.

(a-c) Conditioned medium (CM) from wild-type (WT) and gene-knockout (KO) B16 cells in a proliferative (Pro) or senescent (Sen) state was prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and silver staining (a and b) or antibody microarray-based proteome profiling (c) as in Fig. 2. B16 secretome components are shown, categorized according to the effect of p38α and IKKβ deficiency on their secretion (c): secretion neither dependent on nor suppressed by p38α or IKKβ (I); secretion dependent on p38α (II), IKKβ (III), and both (IV); and secretion suppressed by p38α (V), IKKβ (VI), and both (VII).

(d) RNA from WT and gene-KO B16 cells treated as indicated was analyzed by qPCR (n = 3). NS, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (all relative to WT, 24 h).

Dxr0.5 treatment resulted in the formation of cytoplasmic micronuclei (Supplementary Fig. 3a, Supplemental Digital Content 1), an event known to trigger STING signaling. B16 cells with CRISPR-mediated genetic ablation of STING were not defective in the induction of the ATM-p53-p21 cascade, p38 phosphorylation, and NF-κB nuclear translocation in response to Dxr0.5 (Supplementary Fig. 3, b–d; Supplemental Digital Content 1). Cell cycle arrest and the induction of SA-β-gal activity occurred normally in these cells (Supplementary Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 3, e–g; Supplemental Digital Content 1). The Dxr0.5-induced secretome changes in STING-deficient B16 cells were comparable to those in STING-sufficient control cells (Supplementary Fig. 4, a and b; Supplemental Digital Content 1). STING deficiency, however, prevented Dxr0.5-responsive IRF3 nuclear translocation and IFN-β gene induction (Supplementary Fig. 3, c and d; Supplemental Digital Content 1). These findings indicated that the contribution of STING signaling to the emergence of the senescent phenotype might be highly specific; in Dxr0.5-treated B16 cells, it served mainly to link DNA damage to IFN-β gene transcription.

DNA damage-induced secretome changes in human melanoma cells

The prevalence of senescent cells in human tumors is likely to vary across samples. Clinical melanoma samples were indeed heterogeneous in their p21 protein abundance (Supplementary Fig. 5a, Supplemental Digital Content 1). To assess the significance of tumor cell senescence for the clinical outcomes of melanoma patients, we analyzed senescence-associated protein abundance and SASP component expression in human melanoma tumors using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset. The TCGA melanoma patients (SKCM) were divided based on their reverse-phase protein array signals [50] showing intratumoral p21 protein abundance. The p21-high SKCM group (above the 50th percentile) exhibited a lower survival rate compared to the p21-low counterpart (Supplementary Fig. 5b, Supplemental Digital Content 1), suggesting tumor cell senescence as an event associated with unfavorable prognosis in melanoma. Analysis of the TCGA RNA sequencing dataset, however, revealed that the expression of SASP component genes correlated with patient survival in a gene-specific manner (Supplementary Fig. 5c; Supplemental Digital Content 1): high expression of some genes indicated a better prognosis (negative Cox coefficient) and of others a worse prognosis (positive Cox coefficient). This finding is consistent with the notion that the secretome of senescent cells consists of functionally heterogeneous proteins and exerts mixed effects on tumor fitness and the course of tumor progression.

We examined the response of the human melanoma cell lines A375, MM455, MM608, HS944T, and SKMEL119 to Dxr0.5 exposure. These cell lines harbor an oncogenic BRAF or NRAS allele (BRAFV600E in A375, MM455, and MM608; NRASQ61K/R in HS944T and SKMEL119) as well as other genetic alterations linked to melanomagenesis. While Dxr0.5-induced γ-H2AX formation occurred in all five cell lines, p38 phosphorylation and IκBα degradation varied in extent among them (Supplementary Fig. 6a, Supplemental Digital Content 1). Dxr0.5 exposure resulted in A375 and MM455 cell killing in less than 16 hours, hampering the analysis of their SASP, but spared MM608, HS944T, and SKMEL119 cells and induced changes in their secretome and SASP component expression (Fig. 6, a and b). To investigate whether the p38 and IKK signaling modules contribute to SASP induction in these cells as in B16 cells, we treated them with small-molecule inhibitors of the two protein kinases. Treatment with the IKK inhibitor BMS345541 reduced the viability of MM608 and HS944 cells exposed to Dxr0.5, whereas SKMEL119 cells were refractory to this synthetic lethality (Supplementary Fig. 6, b and c; Supplemental Digital Content 1). The p38 inhibitor SC409 did not sensitize any of the human melanoma cell lines tested to killing by Dxr0.5. Treatment with the p38 and IKK inhibitors suppressed the secretory phenotype of Dxr0.5-exposed SKMEL119 cells, attenuating the induction of SASP component genes (Fig. 6c). Taken together, our genetic ablation and pharmacological inhibition experiments showed that loss of p38 and IKK signaling downstream of ATM suppressed DNA damage-induced secretome changes in mouse and human melanoma cells (Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Fig. 6.

Dxr-induced secretome changes in human melanoma cells.

(a) Conditioned medium (CM) from MM608, HS944T, and SKMEL119 cells in a proliferative (Pro) or senescent (Sen) state was prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and silver staining as in Fig. 2.

(b and c) RNA from MM608, HS944T, and SKMEL119 cells treated as indicated was analyzed by qPCR (n = 3). p38i and IKKi, p38 inhibitor and IKK inhibitor, respectively. NS, not significant; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05 (all relative to 24 h without p38i and IKKi).

Discussion

The principal goal of this work was to establish a melanoma senescence model using a cell line amenable to genetic perturbation and biochemical analysis in vitro as well as engraftment in immunocompetent mice for in vivo studies. We found that B16 cells treated with Dxr0.5 switched from a proliferative to a senescent state within 24 hours. During this transition, drastic cytomorphologic and molecular changes occurred including SASP induction. This approach enabled a straightforward detection of senescence-associated molecular pathways, as DNA double-strand breaks inflicted by Dxr triggered signaling cascades and transcriptional responses that were not only temporally coordinated within individual cells but also synchronized in the Dxr-exposed cell population. This feature is not likely shared by oncogene-induced senescence models that rely on oncogene delivery by plasmid transfection or viral vector transduction. Using B16 cells treated with Dxr, we determined the composition of the secretome of senescent melanoma cells and demonstrated the role of p38α and IKKβ in linking DNA damage to SASP induction.

Dxr treatment resulted in an increase in mRNA encoding SASP components in B16 cells but failed to do so in the absence of p38α and IKKβ. Therefore, these protein kinases are likely to drive the SASP by enhancing the transcription rate or mRNA stability of SASP components. cGAS-STING signaling triggered by the sensing of cytoplasmic DNA has been shown to drive SASP induction [33–35]. We observed that STING deficiency abrogated IFN-β gene induction in Dxr-exposed B16 cells but did not alter their overall protein secretion profile. It should be acknowledged, however, that the experimental condition used in our study might not be ideal for capturing its effects on Dxr-induced secretome changes; a role for STING may be visible under other senescence-inducing conditions or with other temporal windows of analysis.

Given that B16 cells lack p16 and p19 expression due to a large genomic deletion in the Ink4a-Arf locus, p21 likely functions as a key cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that enforces cell cycle arrest during B16 cell senescence. The p38α and IKKβ signaling modules drove DNA damage-induced secretome changes while being dispensable for p21 induction and cell cycle arrest. Inhibition of these protein kinase modules is therefore expected to suppress the production of SASP components and mitigate their effects on the tumor immune microenvironment without restoring the proliferative potential of senescent tumor cells. Of note, the SASP has been linked to both deploying and disrupting immune-mediated antitumor mechanisms [3–6,10]. Therefore, clinical strategies to antagonize the SASP for cancer therapy should target the immunosuppressive arm of the SASP. To enable such selective intervention, future research should identify actionable molecular mechanisms specifically linked to senescence-associated immunosuppression. Manipulation of the SASP by pharmacological means may reshape the tumor immune microenvironment and enhance melanoma responsiveness to immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hensin Tsao for human melanoma cell lines, Roger Greenberg for STING-knockout B16 cells, and David Fisher for discussion and criticism. The results published here are in part based on data generated by the TCGA Research Network. This study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant to J.M.P. (CA182405).

Source of funding: This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant to J.M.P. (CA182405).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Jin Mo Park is a consultant of Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

References

- 1.Bartkova J, Rezaei N, Liontos M, Karakaidos P, Kletsas D, Issaeva N, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature 2006; 444:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Micco R, Fumagalli M, Cicalese A, Piccinin S, Gasparini P, Luise C, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature 2006; 444: 638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 2007; 445:656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang TW, Yevsa T, Woller N, Hoenicke L, Wuestefeld T, Dauch D, et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature 2011; 479:547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iannello A, Thompson TW, Ardolino M, Lowe SW, Raulet DH. p53-dependent chemokine production by senescent tumor cells supports NKG2D-dependent tumor elimination by natural killer cells. J Exp Med 2013; 210:2057–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggert T, Wolter K, Ji J, Ma C, Yevsa T, Klotz S, et al. Distinct Functions of Senescence-Associated Immune Responses in Liver Tumor Surveillance and Tumor Progression. Cancer Cell 2016; 30:533–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert LA, Hemann MT. DNA damage-mediated induction of a chemoresistant niche. Cell 2010; 143:355–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pribluda A, Elyada E, Wiener Z, Hamza H, Goldstein RE, Biton M, et al. A senescence-inflammatory switch from cancer-inhibitory to cancer-promoting mechanism. Cancer Cell 2013; 24:242–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laberge RM, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, Patil CK, Freund A, Zhou L, et al. mTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol 2015; 17:1049–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruhland MK, Loza AJ, Capietto AH, Luo X, Knolhoff BL, Flanagan KC, et al. Stromal senescence establishes an immunosuppressive microenvironment that drives tumorigenesis. Nat Commun 2016; 7:11762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oubaha M, Miloudi K, Dejda A, Guber V, Mawambo G, Germain MA, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype contributes to pathological angiogenesis in retinopathy. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8:362ra144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell 2015; 161:1681–1696.to [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, Yudt LM, Stark M, Robbins CM, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet 2003; 33:19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer J, Curtin JA, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Congenital melanocytic nevi frequently harbor NRAS mutations but no BRAF mutations. J Invest Dermatol 2007; 127:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CM, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature 2005; 436:720–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhomen N, Reis-Filho JS, da Rocha Dias S, Hayward R, Savage K, Delmas V, et al. Oncogenic Braf induces melanocyte senescence and melanoma in mice. Cancer Cell 2009; 15:294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vredeveld LC, Possik PA, Smit MA, Meissl K, Michaloglou C, Horlings HM, et al. Abrogation of BRAFV600E-induced senescence by PI3K pathway activation contributes to melanomagenesis. Genes Dev 2012; 26:1055–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Y, Schleich K, Yue B, Ji S, Lohneis P, Kemper K, et al. Targeting the Senescence-Overriding Cooperative Activity of Structurally Unrelated H3K9 Demethylases in Melanoma. Cancer Cell 2018; 33:322–336.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anders L, Ke N, Hydbring P, Choi YJ, Widlund HR, Chick JM, et al. A systematic screen for CDK4/6 substrates links FOXM1 phosphorylation to senescence suppression in cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2011; 20:620–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie X, Koh JY, Price S, White E, Mehnert JM. Atg7 Overcomes Senescence and Promotes Growth of BrafV600E-Driven Melanoma. Cancer Discov 2015; 5:410–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013; 500:415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell 2015; 160:48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:2189–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Song C, Moreno BH, Hu-Lieskovan S, et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Features of Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma. Cell 2016; 165:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbig U, Jobling WA, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Sedivy JM. Telomere shortening triggers senescence of human cells through a pathway involving ATM, p53, and p21CIP1, but not p16INK4a. Mol Cell 2004; 14:501–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodier F, Coppé JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Muñoz DP, Raza SR, et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11:973–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang C, Xu Q, Martin TD, Li MZ, Demaria M, Aron L, et al. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science 2015; 349:aaa5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banin S, Moyal L, Shieh S, Taya Y, Anderson CW, Chessa L, et al. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science 1998; 281:1674–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canman CE, Lim DS, Cimprich KA, Taya Y, Tamai K, Sakaguchi K, et al. Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science 1998; 281:1677–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:42462–42467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brugarolas J, Chandrasekaran C, Gordon JI, Beach D, Jacks T, Hannon GJ. Radiation-induced cell cycle arrest compromised by p21 deficiency. Nature 1995; 377:552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itahana K, Dimri GP, Hara E, Itahana Y, Zou Y, Desprez PY, et al. A role for p53 in maintaining and establishing the quiescence growth arrest in human cells. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:18206–18214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glück S, Guey B, Gulen MF, Wolter K, Kang TW, Schmacke NA, et al. Innate immune sensing of cytosolic chromatin fragments through cGAS promotes senescence. Nat Cell Biol 2017; 19:1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dou Z, Ghosh K, Vizioli MG, Zhu J, Sen P, Wangensteen KJ, et al. Cytoplasmic chromatin triggers inflammation in senescence and cancer. Nature 2017; 550:402–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi A, Loo TM, Okada R, Kamachi F, Watanabe Y, Wakita M, et al. Downregulation of cytoplasmic DNases is implicated in cytoplasmic DNA accumulation and SASP in senescent cells. Nat Commun 2018; 9:1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu Q, Katlinskaya YV, Carbone CJ, Zhao B, Katlinski KV, Zheng H, et al. DNA-damage-induced type I interferon promotes senescence and inhibits stem cell function. Cell Rep 2015; 11:785–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katlinskaya YV, Katlinski KV, Yu Q, Ortiz A, Beiting DP, Brice A, et al. Suppression of Type I Interferon Signaling Overcomes Oncogene-Induced Senescence and Mediates Melanoma Development and Progression. Cell Rep 2016; 15:171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chicas A, Kapoor A, Wang X, Aksoy O, Evertts AG, Zhang MQ, et al. H3K4 demethylation by Jarid1a and Jarid1b contributes to retinoblastoma-mediated gene silencing during cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:8971–8976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capell BC, Drake AM, Zhu J, Shah PP, Dou Z, Dorsey J, et al. MLL1 is essential for the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Genes Dev 2016; 30:321–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito T, Teo YV, Evans SA, Neretti N, Sedivy JM. Regulation of Cellular Senescence by Polycomb Chromatin Modifiers through Distinct DNA Damage- and Histone Methylation-Dependent Pathways. Cell Rep 2018; 22:3480–3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sen P, Lan Y, Li CY, Sidoli S, Donahue G, Dou Z, et al. Histone Acetyltransferase p300 Induces De Novo Super-Enhancers to Drive Cellular Senescence. Mol Cell 2019; 73:684–698.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flor AC, Wolfgeher D, Wu D, Kron SJ. A signature of enhanced lipid metabolism, lipid peroxidation and aldehyde stress in therapy-induced senescence. Cell Death Discov 2017; 3:17075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fafián-Labora J, Carpintero-Fernández P, Jordan SJD, Shikh-Bahaei T, Abdullah SM, Mahenthiran M, et al. FASN activity is important for the initial stages of the induction of senescence. Cell Death Dis 2019; 10:318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enzler T, Sano Y, Choo MK, Cottam HB, Karin M, Tsao H, et al. Cell-selective inhibition of NF-κB signaling improves therapeutic index in a melanoma chemotherapy model. Cancer Discov 2011; 1:496–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harding SM, Benci JL, Irianto J, Discher DE, Minn AJ, Greenberg RA. Mitotic progression following DNA damage enables pattern recognition within micronuclei. Nature 2017; 548:466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, Georgilis A, Janich P, Morton JP, et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim T, Kim TY, Song YH, Min IM, Yim J, Kim TK. Activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 in response to DNA-damaging agents. J Biol Chem 1999; 274:30686–30689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanchez-Prieto R, Rojas JM, Taya Y, Gutkind JS. A role for the p38 mitogen-acitvated protein kinase pathway in the transcriptional activation of p53 on genotoxic stress by chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Res 2000; 60:2464–2472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bottero V, Busuttil V, Loubat A, Magné N, Fischel JL, Milano G, et al. Activation of nuclear factor κB through the IKK complex by the topoisomerase poisons SN38 and doxorubicin: a brake to apoptosis in HeLa human carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 2001; 61:7785–7791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J, Lu Y, Akbani R, Ju Z, Roebuck PL, Liu W, et al. TCPA: a resource for cancer functional proteomics data. Nat Methods 2013; 10:1046–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.