Abstract

Objective

This meta-analysis examined the prevalence of poor sleep quality and its associated factors in patients with hypertension in China.

Methods

Both English (PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE) and Chinese (Wan Fang Database and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure) databases were systematically and independently searched. The random-effects model was used to estimate the prevalence of poor sleep quality in Chinese patients with hypertension. The funnel plot and Egger’s tests were used to assess publication bias.

Results

The prevalence of poor sleep quality in 24 studies with 13,920 hypertensive patients was 52.5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 46.1–58.9%). In contrast, the prevalence of poor sleep quality in six studies with 5,610 healthy control subjects was 32.5% (95% CI: 19.0–49.7%). In these studies, compared to healthy controls, the pooled odds ratio (OR) of poor sleep quality was 2.66 (95% CI: 1.80–3.93) for hypertensive patients. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses revealed that patients in hospitals were more likely to have poor sleep quality than patients in the community. Studies with smaller sample size, studies using convenience or consecutive sampling and those published in Chinese reported higher prevalence of poor sleep quality. Furthermore, poor sleep quality was more common in older and male hypertensive patients, while the proportion of poor sleep quality was negatively associated with survey year.

Conclusion

Appropriate strategies for screening, prevention, and treatment of poor sleep quality in this population should be developed.

Keywords: poor sleep quality, meta-analysis, hypertension, China, epidemiology

Introduction

Hypertension is a major public health burden and is associated with severe negative health outcomes. The World Health Organization reported that the number of people with raised blood pressure increased from 594 million in 1975 to 1.13 billion in 2015, with the increase mainly occurring in low- and middle-income countries (1). Hypertension-related complications account for approximately 9.4 million deaths worldwide each year, of which around half are due to heart disease and stroke (2, 3). Apart from cardiovascular diseases, other common complications of hypertension include kidney failure, blindness, and cognitive impairment (2).

Symptoms associated with hypertension, such as headache, chest pain, dizziness, shortness of breath, and nose bleeds (2, 4, 5), often lead to poor sleep quality (6). For example, a large-scale population study conducted in China found that patients with hypertension had worse sleep quality than the general population (7). Other studies also found an association between poor sleep quality with hypertension (7–9). Poor sleep quality was associated with increased risk of physical diseases (10, 11), such as obesity (12), and coronary artery disease (13). In addition, poor sleep quality had a bidirectional association with psychiatric disorders (14, 15). For example, persons with poor sleep quality were more likely to develop depression (16) and anxiety (17). In contrast, patients with psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety, were more likely to have poor sleep quality (18, 19). Adequate epidemiological studies of sleep quality in hypertensive patients are important to reduce its negative health consequences and develop appropriate interventions.

The findings of numerous epidemiological surveys of poor sleep quality in hypertensive patients vary greatly, with prevalence ranging from 14.9 to 85.7% globally (20–23). There is growing evidence that socioeconomic and cultural factors may significantly influence sleep patterns and quality (24, 25), therefore sleep quality should be examined separately in different populations. In China the prevalence of hypertension is 29.6%, indicating that there are approximately 325 million patients with hypertension (26). The findings regarding poor sleep quality in Chinese hypertensive patients are inconsistent across studies, which are probably due to different diagnostic tools, study locations, and definitions used. In addition, most studies on prevalence of poor sleep quality in patients with hypertension published in Chinese are generally not accessible to the international readership and have not been included in prior reviews.

To date, no meta-analysis of poor sleep quality in hypertensive patients in China has been reported. Hence, using comparative and epidemiological studies, we conducted a meta-analysis of the pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality in Chinese hypertensive patients and its associated factors. Sleep quality is evaluated either by self-reported or interviewer-rated scales or physiological measures (such as polysomnography and actigraphy) (27). Empirical evidence showed that self-reported measures are user-friendly, reliable, and sensitive to change in sleep patterns and quality (28, 29). Of the different measures on sleep quality, the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) is the most widely used, with satisfactory psychometric properties (30, 31). In China, the Chinese-version of PSQI is the only standardized scale on subjective sleep quality available (32). In order to ensure the homogeneity of included studies, this meta-analysis on sleep quality therefore only included studies using the PSQI.

Methods

Search Strategies

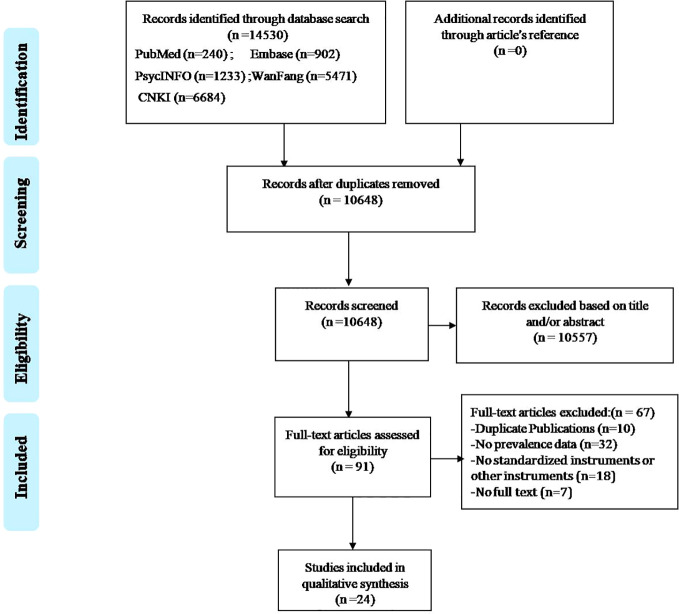

The process of the literature search is shown in Figure 1. Two investigators systematically and independently searched PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, WanFang, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure from their inception date to Sep 16, 2017 with the following search terms: (“China” OR “Chinese” OR “Hong Kong” OR “Taiwan” OR “Macao”) AND (“insomnia” OR “sleep symptom” OR “sleep disorder” OR “sleep quality” OR “sleep disturbance” OR “sleep problem” OR “sleep time” OR “sleep duration” OR “sleep habit” OR “sleep pattern”) AND (“Hypertension” OR “hypertens*” OR “blood pressure” OR “high blood pressure”). The reference lists of the identified papers were also searched for any additional studies that may have been missed.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Study Selection

According to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) recommendation (33), the inclusion criteria based on the PICOS acronym were used in this meta-analysis: Participants (P): patients with hypertension. The diagnosis of hypertension was established according to international diagnostic criteria, such as the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on hypertension (34), or local diagnostic criteria in China, such as the Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension (35); Intervention (I): not applicable; Comparison (C): healthy subjects in case control and cohort studies; and not applicable in cross-sectional studies without control groups, such as epidemiological surveys; Outcomes (O): reported data of poor sleep quality as defined by PSQI cutoff values; and Study design (S): cross-sectional or cohort studies conducted in mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan (only baseline data were extracted in cohort studies). Two investigators (LiLi and J-XC) screened the titles, abstracts, and full-texts of the initial search results independently. Any discrepancies that emerged in these procedures were discussed and resolved by involving a third investigator (LuLi).

Quality Evaluation

Two investigators (LiL and J-XC) independently assessed the methodological quality of the studies using a quality assessment tool consisting of eight items in terms of sampling, measurement, and analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The item scores range between 0 and 8, with a score of 7–8 as high quality, 4–6 as moderate quality, and 0–3 as low quality (36). Disagreements between the two investigators were resolved by discussing with a third investigator (LuL).

Data Extraction

Data were independently extracted by two investigators (LiL and J-XC) and checked by a third investigator (LuL). The following information was extracted and tabulated: study site and time, geographic region, study location, sampling method, mean age, proportion of males, sample size, type of hypertension and cut-off values of instrument on sleep quality, the prevalence of poor sleep quality, and quality assessment. The hospital population refers to the studies that were conducted in hospitals in which participants received treatments, while community population refers to studies of participants with hypertension who lived in the community and received treatments in community clinics or outpatient clinics of general hospitals. In China, maintenance treatments of physical diseases are mainly provided by community clinics or outpatient clinics attached to general hospitals. Hospital- or community-based studies were classified based on the respective study-defined criteria.

Statistical Analyses

The Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Program, Version 2 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, New Jersey, USA) was used to perform the data analysis. Due to different demographic characteristics and sampling methods, data on poor sleep quality were combined using the random-effects model; prevalence and odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were indicated as effect size. The I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test were used to evaluate heterogeneity between studies, with I2 values greater than 50% indicating great heterogeneity (37). In order to examine the moderating effects of associated factors on the results, the subgroup analyses were conducted based on the following categorical variables: community-based studies, publication language, geographic region, age, survey year, sample size, sampling method, and PSQI cut-offs. In addition, meta-regression analyses were conducted to examine the moderating effects of continuous variables, such as age, year of survey, proportion of males, and the sample sizes. Only studies reporting the above-mentioned data were included in subgroup or meta-regression analyses. Median splitting methods of continuous variables, such as age, survey year, and sample size, were used in the subgroup analyses. If the results of subgroup and meta-regression analyses were not consistent, the latter was preferred. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing each study individually to evaluate the consistency of the results. The funnel plot and Egger’s tests were used to assess publication bias. All analyses were two-tailed, with alpha set at 0.05.

Result

Search Results, Studies Characteristics, and Quality Assessment

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the search and selection process. Finally, 24 studies met the inclusion criteria. The PSQI-Chinese version was used in all studies. Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of the included studies which covered 17 provinces and 2 municipalities in mainland China. All studies were rated as “moderate quality” or “high quality”; the mean score of the quality assessment was 5, ranging from 4 to 7.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| No. | First author | Study area (Region) | Year of survey | Study location | Sampling method | Sample size | Mean age | Proportion of male (%) | Type of hypertension | Scale score | Cut-off score | Rate of hypertension (%) | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fang et al. (38) | Shanghai (S) | 2014 | Community | C | 1,606 | 72 (65–80) | 47.14 | NR | 7.61 ± 3.23 | >7 | 43.2 | 5 |

| 2 | Zhang et al. (20) | Hubei (S) | 2014 | Hospital | Conv | 70 | 43.4 ± 10.4 | 60 | Essential/Secondary | 9.73 ± 3.47 | >7 | 85.7 | 6 |

| 3 | Du et al. (39) | Jilin (N) | 2015–2016 | Community | Conv | 208 | 64.6 ± 6.5 | 51.92 | NR | 6.86 ± 2.28 | >7 | 43.75 | 5 |

| 4 | Hu et al. (40) | Hunan (S) | 2013–2014 | Hospital | R | 610 | 67.5 ± 7.1 | 55.74 | Essential | NR | >10 | 47.4 | 6 |

| 5 | Mao et al. (23) | Yunnan (S) | 2015 | Community | C | 793 | 68.0 ± 5.6 | 45.4 | NR | 5.7 ± 2.9 | >7 | 14.9 | 5 |

| 6 | Xiao et al. (41) | Guangdong (S) | 2013–2016 | Hospital | Cons | 176 | 68.0 ± 4.2 | NR | Essential | NR | >7 | 55.68 | 5 |

| 7 | Huang (42) | Fujian (S) | 2013–2014 | Hospital | Cons | 256 | 58.5 (30–80) | 55.86 | Essential | NR | >6 | 32.8 | 5 |

| 8 | Liu et al. (7) | Liaoning (N) | 2012–2013 | Community | M, R | 4,800 | 52.1 ± 14.1 | 50.72 | NR | 5.01 ± 2.71 | >5 | 36.02 | 7 |

| 9 | Ma et al. (43) | Shanxi (N) | 2014 | Hospital | Cons | 135 | 49 ± 6.4 | 100 | Essential | NR | >5 | 71.1 | 5 |

| 10 | Zheng et al. (44) | Fujian (S) | 2013–2014 | Community | Conv | 729 | 60.3 ± 9.2 | 54.32 | Essential | 5.39 ± 2.77 | >7 | 28.67 | 4 |

| 11 | Yu et al. (45) | Chongqing (S) | 2013–2014 | Hospital | Cons | 378 | 54.7 ± 11.8 | 51.06 | Essential | 3.65 ± 2.94 | >5 | 56.35 | 6 |

| 12 | Wei et al. (46) | Guangxi (S) | 2009–2013 | Hospital | Cons | 186 | 70.6 ± 9.7 | 54.84 | Essential | NR | >7 | 48.39 | 5 |

| 13 | Zhang et al. (47) | Zhejiang (S) | 2010–2012 | Community | Cons | 97 | 62.7 (50–78) | 48.45 | NR | NR | >6 | 80.4 | 4 |

| 14 | Zhu et al. (48) | Shanghai (S) | 2012 | Community | R | 457 | 64.7 ± 9.60 | 53.61 | Essential | NR | >6 | 65.34 | 5 |

| 15 | Fang et al. (49) | Hunan (S) | NR | Community | R | 145 | 75.3 ± 12.9 | 55.17 | Essential | 8.98 ± 3.36 | >7 | 45.67 | 6 |

| 16 | Wang et al. (50) | Guangdong (S) | 2012 | Hospital | Cons | 75 | 50.0 ± 8.7 | 57.33 | NR | 7.80 ± 3.95 | >7 | 44 | 4 |

| 17 | Wen et al. (51) | Shanxi (N) | 2012–2013 | Hospital | Cons | 268 | 35–75 | 45.15 | Essential | NR | >7 | 50 | 5 |

| 18 | Luo et al. (52) | Shanghai (S) | NR | Community | C | 629 | NR | NR | NR | NR | >5 | 44.67 | 6 |

| 19 | Dong et al. (53) | Anhui (S) | 2009 | Community | C, R | 1,110 | 69.1 ± 6.87 | 51.89 | NR | 7.65 ± 3.91 | >7 | 42.7 | 5 |

| 54 | Cheng et al. (54) | Guangdong (S) | NR | Community | Cons | 122 | 67.9 ± 6.1 | 54.92 | Essential | 8.34 ± 3.81 | >7 | 63.9 | 5 |

| 21 | Xie et al. (55) | Xinjiang (N) | 2008–2009 | Hospital | Cons | 760 | 56.3 ± 16.6 | 57.5 | NR | 8.42 ± 3.08 | >7 | 62.9 | 5 |

| 22 | Zhang et al. (56) | Guangdong (S) | 2007–2008 | Hospital | Cons | 100 | 74.0 ± 6.3 | 52 | NR | 9.54 ± 3.00 | >7 | 76 | 5 |

| 23 | Sun et al. (57) | NR | 2005–2006 | Hospital | Cons | 139 | 54.6 ± 18.7 | 63.31 | Essential | 10.96 ± 2.33 | >7 | 69.8 | 6 |

| 24 | Zhang et al. (58) | Gansu (N) | NR | Hospital | Cons | 71 | 52.1 ± 12.7 | 64.79 | NR | 10.86 ± 5.10 | >10 | 56.34 | 5 |

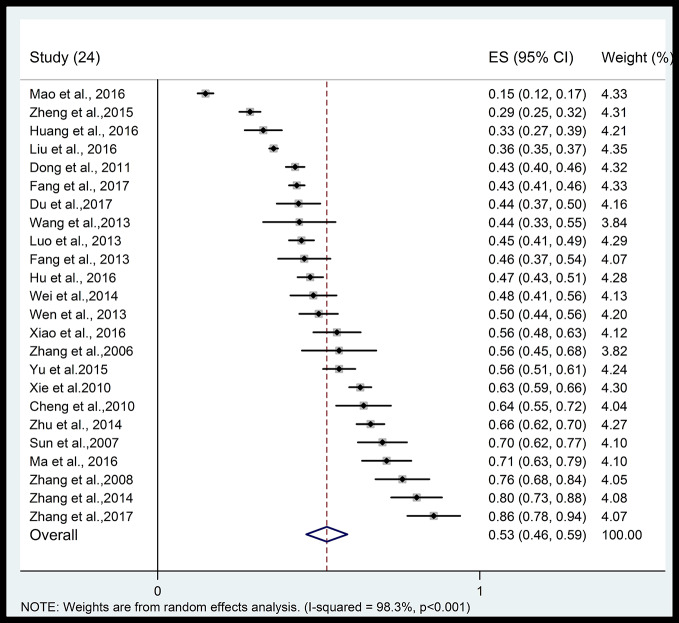

Prevalence of Poor Sleep Quality

Figure 2 shows the forest plot of the prevalence of poor sleep quality. The pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality in 24 studies with 13,920 hypertensive patients was 52.5% (95% CI: 46.1–58.9%) with significant heterogeneity (I2: 98.3%), ranging from 14.9 to 85.7%. The pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality in 6 studies with 5,610 healthy controls was 32.5% (95% CI: 19.0–49.7%) with significant heterogeneity (I2: 98.3%). Supplemental Figure 1 indicates that the hypertensive patients were more likely to have poor sleep quality than healthy controls (OR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.80–3.93) with significant heterogeneity (I2: 89.3%) from the six case-control studies with available data.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of prevalence of poor sleep quality in hypertensive patients.

Subgroup and Meta-Regression Analyses

The results of the subgroup analyses are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of poor sleep quality between different geographical regions. Hypertensive patients in hospitals were more likely to suffer from poor sleep quality than those in the community (58.2 vs. 45.1%, P = 0.012). The prevalence of poor sleep quality was higher in studies published in Chinese than English (53.6 vs. 40.0%, P = 0.016). Studies with smaller sample size reported a higher rate of poor sleep quality (62.3 vs. 42.9%, P = 0.001), while those using convenience or consecutive sampling reported a higher rate of poor sleep quality (41.5 vs. 58.2%, P = 0.005). Meta-regression analyses revealed that the proportion of poor sleep quality was higher in the studies with smaller sample size (β = −0.00012, p < 0.001) and was negatively associated with survey year (β = −0.114, P < 0.001). The poor sleep quality was more common in male patients (β = 3.46, P < 0.001) and in older patients (β = 0.00608, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses.

| Subgroups | Categories (Number of studies) | Proportion (%) | 95% CI(%) | Events | Sample size | I2 (%) | Q (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community | Yes (11) | 45.1 | 37.7–52.8 | 4,119 | 10,696 | 97.8 | 6.32 (0.012) |

| No (13) | 58.2 | 51.4–64.6 | 1,788 | 3,224 | 92.2 | ||

| Geographical region | North (6) | 53.3 | 40.0–66.2 | 2,567 | 6,242 | 98.0 | 0.09 (0.76) |

| South (17) | 51.0 | 43.6–58.3 | 3,243 | 7,539 | 97.1 | ||

| Publication language | Chinese (22) | 53.6 | 46.7–60.4 | 3,899 | 8,491 | 97.0 | 5.80 (0.016) |

| English (2) | 40.0 | 32.0–53.8 | 2,009 | 5,429 | 94.2 | ||

| Age groupa | ≥63.7 (11) | 57.1 | 46.5–67.0 | 3,117 | 7,510 | 97.8 | 1.34 (0.24) |

| <63.7 (11) | 48.9 | 39.9–57.9 | 2,373 | 5,513 | 97.3 | ||

| Survey yeara | 2013–2017 (10) | 46.9 | 36.6–57.4 | 1,952 | 4,961 | 97.7 | 2.28 (0.13) |

| 2007–2012 (10) | 57.9 | 48.2–67.0 | 3,488 | 7,992 | 97.8 | ||

| Sample sizea | ≥232 (12) | 42.9 | 36.0–50.2 | 5,002 | 12,396 | 98.1 | 11.8 (0.001) |

| <232 (12) | 62.3 | 54.1–69.9 | 903 | 1,524 | 89.7 | ||

| Sampling method | Probability (8) | 41.5 | 33.9–49.5 | 3,950 | 10,150 | 98.0 | 8.03 (0.005) |

| Non-probability (16) | 58.2 | 49.8–66.1 | 1,955 | 3,770 | 95.6 | ||

| Cut-off of CPSQI | >5 (4) | 51.7 | 39.2–63.8 | 2,319 | 5,942 | 50.4 | 0.52 (0.91) |

| >6 (3) | 60.5 | 33.8–82.2 | 461 | 810 | 97.5 | ||

| >7 (15) | 51.1 | 42.6–59.5 | 2,796 | 6,487 | 97.7 | ||

| >10 (2) | 50.1 | 42.1–58.1 | 329 | 681 | 97.3 |

Bolded values: P < 0.05; Q: Cochran’s Q;

a: Continuous variables, such as age, survey year and sample size, were dichotomized using median splitting methods in the subgroup analyses. CPSQI: Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Probability sampling method: cluster sampling; multistage sampling; random sampling; stratified sampling; Non-probability sampling method; convenience and consecutive sampling.

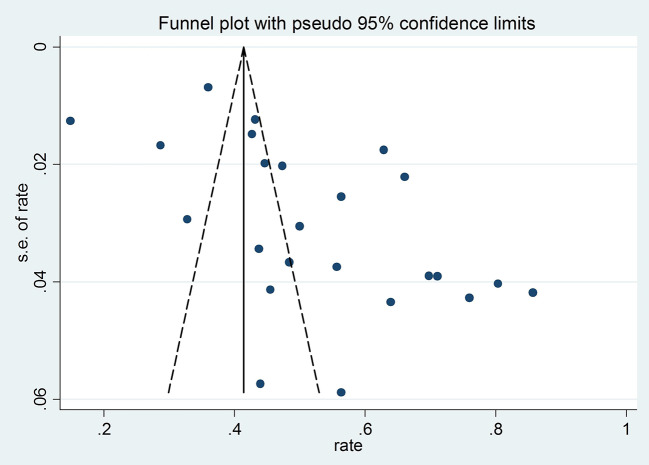

Publication Bias

Visual funnel plot and the Egger’s tests (t = 6.18, P < 0.001) both indicated significant publication bias (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of publication bias for 24 studies with available data on prevalence of poor sleep quality.

Sensitivity Analysis

When studies were excluded one by one, the recalculated results did not change significantly. Therefore, no individual study significantly influenced the primary results.

Discussion

This was the first meta-analysis of the prevalence of poor sleep quality in hypertensive patients in China. We found that more than half of the patients with hypertension had poor sleep quality, which is around two times higher than in healthy controls (OR: 2.66). There were approximately 325 million hypertensive patients in China, which translates to around 170.6 million hypertensive patients with poor sleep quality based on a prevalence of 52.5% (26). Several factors may be associated with the increased rate of poor sleep quality in hypertensive patients. First, hypertension symptoms, such as pain and headache (5), are associated with sleep problems, such as poor sleep quality (59). Several studies found that poor sleep quality in hypertension could offset the effects of blood pressure control (60). In addition, poor sleep quality is usually significantly associated with impaired physical functioning and poor mental health in patients with hypertension (21); therefore, improving sleep quality might be beneficial in improving both mental health and hypertension. Second, hormones involved in the regulation of the sleep/wake cycle could reduce systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, and enhance nocturnal systolic and diastolic blood pressure dipping in hypertensive patients (61). Thus, long-term poor sleep quality could disturb the rhythm of body clock and influence catecholamine secretion, which may result in high blood pressure. Third, there is a close association between sleep and high blood pressure since both are linked to the activities of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (62, 63). For example, untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is significantly related to the development of hypertension; OSA can result in intermittent hypoxemia and cause oxidative stress, which is associated with increased sympathetic activity by the HPA axis, and hence elevated blood pressure (64).

The subgroup analyses found that hypertensive patients in hospitals had a higher risk of poor sleep quality than those in the community (58.2 vs. 45.1%, P = 0.012). It is likely that patients in hospitals could have more severe hypertension and more comorbidities, which could increase the risk of poor sleep quality. Similar to other studies (65), there was a positive association between poor sleep quality and older age. On the one hand, both sleep duration and quality usually decrease with age. On the other hand, older adults usually have low levels of outdoor activities and high rates of physical and psychological problems, such as diabetes, dementia, respiratory disease, and depression, all of which could increase the risk of poor sleep quality (66, 67).

Unlike previous findings (7, 22, 68), we found that male patients were more likely to have poor sleep quality (β = 3.46, P < 0.001), which could be attributed to gender difference in the use of sleep promoting medications in China although medication use was not analyzed in this meta-analysis due to inadequate information. Compared with males, Chinese females with sleep problems are more likely to accept sleep promoting medications (68), which may improve sleep quality.

Studies with small sample size reported a higher rate of poor sleep quality (β = −0.00012, p < 0.001), while those using convenience or consecutive sampling also reported a higher rate of poor sleep quality. We assumed that studies with small sample size and those using convenience or consecutive sampling may have relatively unstable results (69). We also found a negative association between poor sleep quality rate and year of survey (β = −0.114, P < 0.001). This is perhaps due to remarkable increases in coverage and utilization of healthcare resources seen in recent years in China (70), which could reduce the risk of poor sleep quality. The funnel plot and Egger’s tests indicated that publication bias exist, but the exact reasons are unclear. The possible reasons may be that studies with a small sample size and/or those with a lower prevalence of poor sleep quality were less likely to be published by academic journals, which could result in publication bias (71). In addition, the prevalence of poor sleep quality in studies published in Chinese appeared to be higher than those published in English, which is probably due to the very small number of studies in the English group (n = 2).

The strength of this meta-analysis includes the moderate-high quality of the included studies that were conducted across broad regions of China. However, several limitations should be considered. First, certain factors related to sleep quality in hypertensive patients, such as education level, physical exercise, anti-hypertensive treatments, and duration of hypertension, were not examined due to inadequate data. In addition, poor sleep quality had a bidirectional association with psychiatric disorders (14, 15). However, psychiatric comorbidities in hypertensive patients were not reported in most of the included studies, therefore, their moderating effects on the results could not be examined. Second, similar to other meta-analyses of epidemiology (72–74), there was significant heterogeneity of prevalence estimate across studies probably due to the discrepancy in study year, psychiatric and somatic comorbidities, sampling methods, and demographic characteristics of patients (75). The substantial heterogeneity in the subgroup analyses is usually unavoidable in meta-analyses of observational and epidemiological surveys (75–78) even if the subgroup analyses are conducted. Third, several studies had a small sample size and/or used non-random sampling, which probably had contributed to the publication bias (79, 80). Fourth, the potential confounding effects between moderating variables could not be controlled for because the statistical programs used in this study could only perform univariate analyses. Finally, the PSQI is the only standardized scale on subjective sleep quality available in China, which therefore could reduce the possibility of missing relevant studies in this meta-analysis. However, those using objective measures (e.g., polysomnography) on sleep quality were not included.

In conclusion, more than half of the Chinese patients with hypertension in this meta-analysis suffered from poor sleep quality which was significantly associated with male gender and older age. Considering the negative impact of sleep quality, appropriate strategies for the screening, prevention, and treatment of poor sleep quality in hypertensive patients should be developed.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

Study design: LiL, Y-TX. Data collection, analysis, and interpretation: LiL, LuL, J-XC, LX. Drafting of the manuscript: LiL, Y-TX. Critical revision of the manuscript: CN, GU.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for investigational new drug (2018ZX09201-014), the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z181100001518005), the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS) and Science and Technology Plan Project of Guangdong Province (No.2019B030316001).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00591/full#supplementary-material.

References

- 1. Risk Factor Collaboration NCD. Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19.1 million participants. Lancet (2017) 389(10064):37–55. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31919-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization A Global Brief on Hypertension; Silent Killer, Global Public Health Crisis. Geneva: World Health Organization; (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet (2008) 371(9623):1513–8. 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60655-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sacco M, Meschi M, Regolisti G, Detrenis S, Bianchi L, Bertorelli M, et al. The relationship between blood pressure and pain. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) (2013) 15(8):600–5. 10.1111/jch.12145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gipponi S, Venturelli E, Rao R, Liberini P, Padovani A. Hypertension is a factor associated with chronic daily headache. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol (2010) 31 Suppl 1:S171–3. 10.1007/s10072-010-0322-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rabner J, Kaczynski KJ, Simons LE, LeBel A. Pediatric Headache and Sleep Disturbance: A Comparison of Diagnostic Groups. Headache (2018) 58(2):217–28. 10.1111/head.13207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu RQ, Qian Z, Trevathan E, Chang JJ, Zelicoff A, Hao YT, et al. Poor sleep quality associated with high risk of hypertension and elevated blood pressure in China: results from a large population-based study. Hypertens Res (2016) 39(1):54–9. 10.1038/hr.2015.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas SJ, Calhoun D. Sleep, insomnia, and hypertension: current findings and future directions. J Am Soc Hypertens (2017) 11(2):122–9. 10.1016/j.jash.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu L, He Y, Jiang B, Liu M, Wang J, Zhang D, et al. Association between sleep duration and the prevalence of hypertension in an elderly rural population of China. Sleep Med (2016) 27-28:92–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McKinnon A, Terpening Z, Hickie IB, Batchelor J, Grunstein R, Lewis SJ, et al. Prevalence and predictors of poor sleep quality in mild cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol (2014) 27(3):204–11. 10.1177/0891988714527516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keskindag B, Karaaziz M. The association between pain and sleep in fibromyalgia. Saudi Med J (2017) 38(5):465–75. 10.15537/smj.2017.5.17864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. St-Onge MP. Sleep-obesity relation: underlying mechanisms and consequences for treatment. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes (2017) 18 Suppl 1:34–9. 10.1111/obr.12499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King CR, Knutson KL, Rathouz PJ, Sidney S, Liu K, Lauderdale DS. Short sleep duration and incident coronary artery calcification. Jama (2008) 300(24):2859–66. 10.1001/jama.2008.867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roberts RE, Duong HT. The prospective association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents. Sleep (2014) 37(2):239–44. 10.5665/sleep.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McMakin DL, Alfano CA. Sleep and anxiety in late childhood and early adolescence. Curr Opin Psychiatry (2015) 28(6):483–9. 10.1097/yco.0000000000000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu BP, Wang XT, Liu ZZ, Wang ZY, An D, Wei YX, et al. Depressive symptoms are associated with short and long sleep duration: A longitudinal study of Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord (2020) 263:267–73. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cook F, Conway LJ, Giallo R, Gartland D, Sciberras E, Brown S. Infant sleep and child mental health: a longitudinal investigation. Arch Dis Child (2020) 105(7):1–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-318014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rothe N, Schulze J, Kirschbaum C, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Penz M, Wekenborg MK, et al. Sleep disturbances in major depressive and burnout syndrome: A longitudinal analysis. Psychiatry Res (2020) 286:112868. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vancampfort D, Van Damme T, Stubbs B, Smith L, Firth J, Hallgren M, et al. Sedentary behavior and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance among 181,093 adolescents from 67 countries: a global perspective. Sleep Med (2019) 58:19–26. 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang ZY, Peng YL. Investigation of the Sleep Quality of Young and Middle-age Hospitalized Patients with Hypertension in Class III Grade I Hospitals in Hubei Province (in Chinese). Nurs J Chin People’s Liberation Army (2017) 34(09):63–6+70. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Batal O, Khatib OF, Bair N, Aboussouan LS, Minai OA. Sleep quality, depression, and quality of life in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Lung (2011) 189(2):141–9. 10.1007/s00408-010-9277-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Prejbisz A, Kabat M, Januszewicz A, Szelenberger W, Piotrowska AJ, Piotrowski W, et al. Characterization of insomnia in patients with essential hypertension. Blood Press (2006) 15(4):213–9. 10.1080/08037050600963040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mao Y, Zhou J, Chu TS. Association of sleep quality witll hypertension in the elderly of Jino nationality: A multilevel model analysis (in Chinese). Chin Med J (2016) 96(46):3757–61. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.46.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gureje O, Makanjuola VA, Kola L. Insomnia and role impairment in the community : results from the Nigerian survey of mental health and wellbeing. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2007) 42(6):495–501. 10.1007/s00127-007-0183-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ohayon MM, Partinen M. Insomnia and global sleep dissatisfaction in Finland. J Sleep Res (2002) 11(4):339–46. 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang J, Zhang L, Wang F, Liu L, Wang H. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: results from a national survey. Am J Hypertens (2014) 27(11):1355–61. 10.1093/ajh/hpu053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep (2014) 37(1):9–17. 10.5665/sleep.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palermo TM, Toliver-Sokol M, Fonareva I, Koh JL. Objective and subjective assessment of sleep in adolescents with chronic pain compared to healthy adolescents. Clin J Pain (2007) 23(9):812–20. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318156ca63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baker FC, Maloney S. Driver HS. A comparison of subjective estimates of sleep with objective polysomnographic data in healthy men and women. J Psychosom Res (1999) 47(4):335–41. 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00017-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pan CW, Cong X, Zhou HJ, Li J, Sun HP, Xu Y, et al. Self-Reported Sleep Quality, Duration, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Chinese: Evidence From a Rural Town in Suzhou, China. J Clin Sleep Med (2017) 13(8):967–74. 10.5664/jcsm.6696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, Su CT, Yang TT, Huang CJ, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res (2005) 14(8):1943–52. 10.1007/s11136-005-4346-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu JC, Tang MQ, Hu H. Study on the reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index(in Chinese). Chin J Psychiatry (1995) 29:103–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, DG A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PloS Med (2009) 6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mansia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, et al. ESH-ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Blood Press (2007) (2007):135–232. 10.1080/08037050701461084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu LS. Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension (inChinese). Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi (2010) 39(7):579–615 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boyle MH. Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies. Evid Based Mental Health (1998) 1:37–9. 10.1136/ebmh.1.2.37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (2003) 327(7414):557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fang H, Wang N, Zhang GF, Cheng WJ. Investigation of sleep quality of hypertensive elderly in a comunity of Shanghai (in Chinese). Chin J Clin Med (2017) 24:451–4. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Du JL, Zhou XD. The effect of social support on sleep quality in elderly patients with hypertension (in Chinese). J Chin gerontology (2017) 37:2555–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hu XX, Xu WF. Sleep quality and the rate of reaching target morning blood pressure surge in elderly patients with essential hypertension (in Chinese). Chin Ment Health J (2016) 30:492–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xiao YQ, Zhang ZM. The relationship between sleep disturbance and morning peak blood pressure in elderly patients with hypertension (in Chinese). Shenzhen J Integrated Traditional Chin Western Med (2016) 26:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang LJ, Ye LF. The effect of sleep disorder on early morning blood pressure in patients with hypertension (in Chinese). J Baotou Med Coll (2016) 32:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ma HH, Ma YM. The effect of sleep condition on male adults with hypertension (in Chinese). J Clin Res (2016) 33:2250–2. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zheng JS, Yang LQ, Chen SH. Analysis of Canonical Correlation between Security and Sleep Quality among Hypertensive Patients in Communities (in Chinese). J Liaoning Med Coll (2015) 36:93–5. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yu HB, Li J. Study on relationship between sleep quality and blood pressure control in outpatient hypertension patients (in Chinese). Chongqing Med J (2015) 44:2561–3. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wei YH, Pan RD. The effect of sleep disorder on elderly hypertension patients (in Chinese). Jilin Med J (2014) 35:4903–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang J. Study on sleep quality and social support for the study of elderly hypertension in the community (in Chinese). Med Inf (2014) 27:81–1. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhu WF, Sun JX. Study on the correlation between hypertension disease and sleep disorders (in Chinese). J Pract Med (2014) 30:139–42. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fang ZH, Yang JJ, He D, Zhou J. Study on sleep quality of patients of essential hypertension in elderly population in the community (in Chinese). China modern Med (2013) 20:170–1. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang XD, Chen Y. The study on the sleep situation and its related factors in the hospitalized patients with hypertension (in Chinese). Guangdong Med J (2013) 34:712–4. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wen L, Yang XY. Study on sleep quality and its related factors in hypertension patients with different gender (in Chinese). China Health Care Nutrtion (2013) 23:4366–6. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Luo J, Zhu G, Zhao Q. Prevalence and risk factors of poor sleep quality among Chinese elderly in an urban community: results from the Shanghai aging study. PloS One (2013) 8:e81261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dong Q, Li J, Liu JJ. Infuencing factors of sleep quality among rural elderly with hypertension in Anhui province (in Chinese). China Public Health (2011) 27:831–3. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cheng MF, Wang XL, Zhong ZM. Relationship between sleep disorder and treatment strategy in elderly patients with primary hypertension (in Chinese). J Chin Health manage (2010) 4:168–70. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xie XH. The effect of sleep quality on blood pressure in hypertension patients with two different ethnic (in Chinese). Chin J Misdiagnostics (2010) 10:4565–6. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang LJ, Xiong Q. A study on the sleep condition and its influence factors in old patients with hypertension (in Chinese). Chin J Pract Nurs (2008) 24:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sun LW, Wang TQ. Investigation of the subjective somnus quality and the symptom checkIist-90 in the patients with hypertension preliminary diagnosed (in Chinese). Chin J Cardiovasc Rehabil Med (2007) 16:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang JQ, Zhang XW. Relationship between the Sleep Quality and Anxiety-depression of Hypertension Patients (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol (2006) 14:117–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Holland PR. Headache and sleep: shared pathophysiological mechanisms. Cephalalgia Int J Headache (2014) 34(10):725–44. 10.1177/0333102414541687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pepin JL, Borel AL, Tamisier R, Baguet JP, Levy P, Dauvilliers Y. Hypertension and sleep: overview of a tight relationship. Sleep Med Rev (2014) 18(6):509–19. 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Portaluppi F, Vergnani L, Manfredini R, Fersini C. Endocrine mechanisms of blood pressure rhythms. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1996) 783:113–31. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb26711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gold SM, Dziobek I, Rogers K, Bayoumy A, McHugh PF, Convit A. Hypertension and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity affect frontal lobe integrity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2005) 90(6):3262–7. 10.1210/jc.2004-2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Balbo M, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep and its disturbances on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Int J Endocrinol (2010) 2010:759234. 10.1155/2010/759234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hou H, Zhao Y, Yu W, Dong H, Xue X, Ding J, et al. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Global Health (2018) 8(1):010405. 10.7189/jogh.08.010405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Avidan AY. Sleep disorders in the older patient. Prim Care (2005) 32(2):563–86. 10.1016/j.pop.2005.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hu M, Zhang P, Li C, Tan Y, Li G, Xu D, et al. Sleep disturbance in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of objective measures. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol (2017) 38(8):1363–71. 10.1007/s10072-017-2975-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Newman AB, Enright PL, Manolio TA, Haponik EF, Wahl PW. Sleep disturbance, psychosocial correlates, and cardiovascular disease in 5201 older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc (1997) 45(1):1–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lu L, Wang SB, Rao W, Zhang Q, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. The Prevalence of Sleep Disturbances and Sleep Quality in Older Chinese Adults: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Behav Sleep Med (2019) 17(6):1–15. 10.1080/15402002.2018.1469492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cao XL, Wang SB, Zhong BL, Zhang L, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. The prevalence of insomnia in the general population in China: A meta-analysis. PloS One (2017) 12(2):e0170772. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y, Qian J, Cai M, Xin Y, et al. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: a cross-sectional study. Lancet (2012) 379(9818):805–14. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60278-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wu J, Wu H, Lu C, Guo L, Li P. Self-reported sleep disturbances in HIV-infected people: a meta-analysis of prevalence and moderators. Sleep Med (2015) 16(8):901–7. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang ZD, Wang SC, Liu HH, Ma HY, Li ZY, Wei F, et al. Prevalence and burden of Toxoplasma gondii infection in HIV-infected people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV (2017) 4(4):e177–e88. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30005-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chen SJ, Shi L, Bao YP, Sun YK, Lin X, Que JY, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev (2018) 40:43–54. 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Jones L, Wood S, Bates G, Eckley L, et al. Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet (2012) 379(9826):1621–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61851-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bubu OM, Brannick M, Mortimer J, Umasabor-Bubu O, Sebastiao YV, Wen Y, et al. Sleep, Cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep (2017) 40(1):1–18. 10.1093/sleep/zsw032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Winsper C, Ganapathy R, Marwaha S, Large M, Birchwood M, Singh SP. A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of aggression during the first episode of psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2013) 128(6):413–21. 10.1111/acps.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Long J, Huang G, Liang W, Liang B, Chen Q, Xie J, et al. The prevalence of schizophrenia in mainland China: evidence from epidemiological surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2014) 130(4):244–56. 10.1111/acps.12296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Li Y, Cao XL, Zhong BL, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, Lai KY, et al. Smoking in male patients with schizophrenia in China: A meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend (2016) 162:146–53. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Light RJ. Accumulating evidence from independent studies: what we can win and what we can lose. Stat Med (1987) 6(3):221–31. 10.1002/sim.4780060304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Angell M. Negative studies. New Engl J Med (1989) 321(7):464–6. 10.1056/nejm198908173210708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.