Dear editor,

A recent report in the present journal focused on the decreased incidence of tuberculosis during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan.1 A declining trend in influenza following the COVID-19 outbreak has already been indicated in Brazil, Singapore and Japan.2, 3, 4 According to the Infectious Diseases Weekly Report Japan,5 besides influenza, the incidences of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia, respiratory syncytial virus infection, infectious gastroenteritis, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis and other droplet or contact transmission diseases are also markedly lower than those in the same periods in previous years.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about lifestyle changes, including the encouragement of wearing masks, handwashing, maintaining social distance and suspension of mass gatherings. These prevention measures for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission may have contributed to a decline in many types of infectious diseases. Lai et al. suggested that these interventions for infection control may also positively influence pulmonary tuberculosis.1 However, whether or not the decline in tuberculosis incidence is actually due to these prevention measures, as with other respiratory infectious diseases, is unclear.

Tuberculosis can be pathologically divided into primary and secondary (reactivation) tuberculosis. An increase in the numbers of elderly patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis has been observed worldwide, and this disease typically develops as a result of reactivation of a latent tuberculosis infection a long time, usually several dozen years, after the initial tuberculosis infection.6 As such, the infection control measures enacted to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission a short time after the COVID-19 outbreak are not expected to influence the trend in tuberculosis incidence.

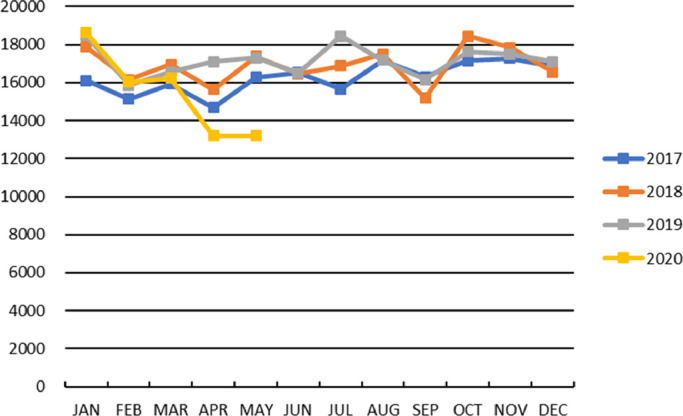

In Japan, as seen in Taiwan, the number of patients newly diagnosed with tuberculosis has significantly decreased since the COVID-19 outbreak, especially in March 2020 (Fig. 1 ).7 As Lai et al. mentioned, the number of tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection may be confounded with whether or not the COVID-19 outbreak reduced the rate of tuberculosis identification through alternations in the behavior of symptomatic individuals seeking medical attention or in physicians’ inclination to test for M. tuberculosis. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic required lockdowns in many areas and restricted access to hospitals, especially for people with non-emergent symptoms.8 Medical checkups have also been canceled or delayed. Such a situation can deprive physicians of opportunities to suspect tuberculosis infection and test for M. tuberculosis.

Fig. 1.

Number of patients newly diagnosed with tuberculosis in Japan. The incidence in each month differed significantly among 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 (p < 0.01 for each by chi-square test), and the incidence in 2020 was significantly lower than that in 2017, 2018, or 2019 from February to April (p < 0.002 for each by Ryan's multiple comparison test). In April, no significant difference was noted in the incidence among 2017, 2018, and 2019, but the incidence in April 2020 was significantly lower than that in 2017, 2018, or 2019. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We therefore examined data regarding the number of acid-fast bacteria cultures submitted to the SRL, the largest commercial laboratory in Japan, and compared changes from January to May in 2020 with the same period in 2017, 2018, and 2019. The data were kindly provided by SRL. Our results showed that the number of tests decreased starting in April in 2020, and the numbers of tests in April and May 2020 were significantly lower than those in the same period of 2017–2019, as shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Number of acid-fast bacteria cultures reviewed at the largest commercial laboratory in Japan. The number of tests per month differed significantly among 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 (p < 0.01 for each by chi-square test), and the number in 2020 was significantly lower than that in 2017, 2018, or 2019 in April and May (p < 0.002 for each by Ryan's multiple comparison test). In April, no significant difference was noted in the number between 2018 and 2019, but the number in April 2020 was significantly lower than that in 2017, 2018, or 2019. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Consequently, the statistical decline in tuberculosis incidence following the COVID-19 outbreak is likely to have been influenced by the decreased number of tests for M. tuberculosis and may not reflect the true incidence of tuberculosis in Japan. Because the reactivation of tuberculosis among the elderly cannot be controlled by short term measures for preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission, physicians need to be aware of the possibility of underestimated tuberculosis infection and carefully examine elderly patients considering the likelihood of tuberculosis infection.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Mr. Shinya Takano (SRL, Tokyo, Japan) for providing data.

References

- 1.Lai C.C., Yu W.L. The COVID-19 pandemic and tuberculosis in Taiwan. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Souza Luna L.K., Perosa D.A.H., Conte D.D. Different patterns of Influenza A and B detected during early stages of COVID-19 in a university hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow A., Hein A.A., Kyaw W.M. Unintended Consequence: influenza plunges with public health response to COVID-19 in Singapore. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakamoto H., Ishikane M., Ueda P. Seasonal Influenza Activity During the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak in Japan. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1969–1971. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health LaW, Diseases NIoI. Infect Dis Wkly Rep Jpn. 2020;22(22) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori T., Leung C.C. Tuberculosis in the global aging population. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24(3):751–768. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Research Institute of Tuberculosis JATA. Statistics of Tuberculosis from the Tuberculosis Surveillance Center. http://www.jata.or.jp/rit/ekigaku/. assessed 21 June 2020.

- 8.Comelli I., Scioscioli F., Cervellin G. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on census, organization and activity of a large urban Emergency Department. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parm. 2020;91(2):45–49. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]