Abstract

Background

Periprosthetic bone remodeling, which is a phenomenon observed in all femoral stems, has a multifactorial origin as it depends on factors related to the patient, the surgical technique, and the design of the implant. To determine the pattern of remodeling produced by 2 models of anatomic cementless implants, we quantified the changes in bone mineral density (BMD) in the 7 areas of Gruen observed at different moments after surgery during the first postoperative year.

Methods

A prospective, comparative, controlled, 1-year follow-up densitometric study was carried out in 2 groups of patients suffering from primary unilateral hip osteoarthritis. In the first group, with 68 patients, an ABG-II stem was implanted. In the second, with 66 patients, the ANATO stem was used. The contralateral, healthy hip was taken as a control.

Results

Both groups showed a decrease in BMD at 3 months in all the areas, which recovered at the end of the study, except in zone 7: there was a 17.7% decrease in the ABG-II group and a 5.9% decrease in the ANATO group. In zones 2 and 6, where more loads are transmitted, conservation of BMD is observed in response to Wolff's law. The differences in the pattern of remodeling between groups were maintained despite the age, gender, and BMI of the patients or the size of the implants.

Conclusion

The ANATO stem achieved a more efficient transmission of loads at the metaphyseal level, which promotes bone preservation at the proximal femur, than the ABG-II stem.

Keywords: Hip, Total arthroplasty, Bone densitometry, Periprosthetic remodeling

Introduction

Bone remodeling after a hip arthroplasty occurs with all models of cementless femoral stems because of the change in the pattern of load transmission produced after the surgery. The magnitude of these adaptive changes is multifactorial, with factors attributable to the patient, to the surgical technique, and to the implant [[1], [2], [3], [4]].

On another note, it is accepted that a decrease of 30%-40% in the bone mineral density (BMD) is necessary to appreciate changes in the bone density in a simple radiograph [5]. For this reason, dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry is considered the ideal method to quantify the changes in BMD produced by different stems over the years [[6], [7], [8]]. For the location of the changes, the Gruen zones have been used as a reference. Zone 1 corresponds to the greater trochanter, zone 7 to the lesser trochanter, and zone 4 is distal to the tail of the implant. Zones 2 and 3 correspond to the external portion of the middle and distal third of the femur around the implant, respectively. Zones 6 and 5 correspond to the internal portion of the middle and distal third, respectively.

In the last 2 decades, several clinical studies and results of national registries of the ABG-I stem (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) showed good clinical and radiological evolution [9,10]. However, in densitometric studies, this implant produced a 12% decrease in BMD in zone 1 and 27% in zone 7 at the end of the first postoperative year. The redesign of this implant (ABG-II; Stryker) in the late 1990s maintained good clinical and radiological results, improving the results of bone remodeling [11] but still showing a decrease in BMD of 7% in zone 1 and 16% in zone 7 [12].

In 2015, the evolution of the ABG-II stem (ANATO, Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) was marketed. This new implant has 2 options of the femoral neck, is made with a different titanium alloy, and also has a biological coating of greater porosity, which is different from the grit-blasted surface of the ABG-II stem. Finally, the length of the ANATO stem does not increase after size 4, always measuring 120 mm from that size onward. When this new stem was used in our department, a pilot study was carried out with the first 37 patients who received this implant. The results showed a reduced decrease in bone mass at the proximal femur, particularly in area 7 [13], compared with the ABG-II stem [11,12].

With the intention of confirming these findings and avoiding the bias of studies carried out in different time periods, by different surgeons and with modifications in the surgical technique and postoperative care, a prospective comparative study including both implants was designed and subsequently carried out in 2017. The purpose of this study was to quantify the variation of the periprosthetic BMD caused by these 2 implants throughout the first 12 postoperative months, taking the contralateral, healthy hip as a control.

Material and methods

To quantify the periprosthetic bone remodeling caused by the ABG-II and ANATO stems, a prospective, comparative, densitometric study was designed, taking the contralateral, healthy hip as a control. The patients included in the study were operated between March and September 2017. The clinical data were obtained from the clinical history and radiograph. The study was completed with the functional assessment of the operated hip using the Merle D’Aubigne Postel score and radiographs anteroposterior of the pelvis and axial of the affected hip) at the same time that each densitometric study was carried out. The study was approved by the ethics committee.

Densitometric evaluation

The variation of the BMD was used as a criterion of evolution in boxes of 30-by-30 pixels in each of the 7 areas of the Gruen zones in both the healthy and the operated hips. BMD determinations were performed using the LUNAR DPX enCORE densitometer (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI) using metal exclusion software. The analyses were made with a careful superimposition of the stem in all the scans of each patient to analyze the same regions of interest. The scans in both hips were made preoperatively and 1 year after the surgery. In the operated hip, 3 additional determinations were made: in the immediate postoperative period and 3 and 6 months after the surgery. The densitometric results were compared grouping the patients based on the stem used and analyzing any possible differences between the age, gender, weight, and size of the implant.

To ensure the reliability of the scans [14] and reproduce the position of the hip during the densitometric study, all the patients were placed in the supine position on the scanner table, with the knees and hips in extension and the whole limb in a neutral position supported on a rigid plastic device that immobilized the leg with Velcro tapes.

Study population

The patients included in the study suffered from unilateral hip osteoarthritis, Dorr A femoral morphology, with no radiological signs of osteoporosis. They had a healthy contralateral hip and accepted to participate in the study.

The patients were included in 2 groups depending on the day of inclusion on the surgical waiting list (even days: ABG-II [Stryker]; odd days: ANATO). It was proposed to include a minimum of 60 patients in each group, and finally 68 were included in the ABG-II group and 66 in the ANATO group. All patients completed the 1-year follow-up.

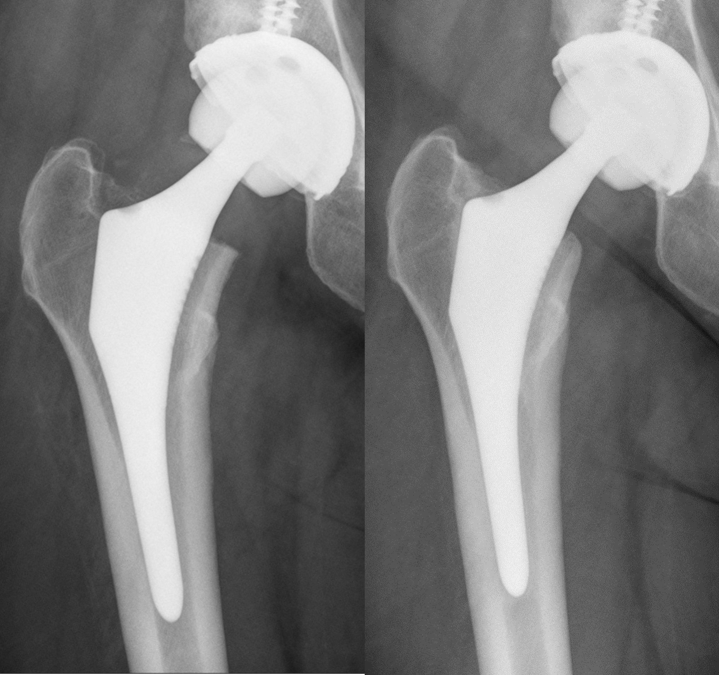

The implant used in the first group was the ABG-II stem and, in the second group, the ANATO® stem (Stryker), with uncemented cup (TRIDENT PSL®, Stryker, Kalamzazoo, MI) and ceramic-polyethylene bearing couple (the latter 2 were not part of the study). The ABG-II stem is an uncemented anatomical stem, of metaphyseal press fit, made with an alloy of titanium-molybdenum-zinc-iron, with a 7-degree femoral neck anteversion. At the metaphyseal level, it has a scale-like design on the anterior and posterior sides of the implant, with a grit-blasted surface and a hydroxyapatite coating of 70 microns. The ANATO stem is made of titanium-aluminum-vanadium (Fig. 1a and b). It has 2 femoral neck options: neutral or with 7 degrees of anteversion. At the metaphyseal level, it also has a scale-like design on the anterior and posterior sides of the implant, which helps transform the axial forces into transverse ones, improving the stability of the implant. At this level, the surface is rough, created with a 300-micron titanium spray and a 50-micron PureFix® (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) hydroxyapatite coating. From size 4, the total length of bigger implants does not increase, always limited to 120 mm. It has the same offsets and neck lengths as the ABG-II® stem.

Figure 1.

(a) ABG-II stem. (b): ANATO stem.

Surgical technique

All the patients were operated on using a posterolateral approach performed by the same group of 5 surgeons. Antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin, or teicoplanin in case of allergy, was used in the first 24 postoperative hours, and antithrombotic prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparins was used for the following 30 days.

The patients rested in bed for the first 24 hours, after which the drainage of the wound was removed. From that moment, sitting on the edge of the bed or in a high chair was started. Next, walking with crutches or a walker was authorized, in partial weight-bearing, according to tolerance. To minimize micromovement that can affect bone growth on the surface of the implant, and the risk of periprosthetic fractures, the patients continued using the crutches for 6 weeks, and later, using just one crutch, progressive full loading was authorized. After 3 months, complete weight-bearing without any supportive help and free movement was authorized.

Statistical analysis

The statistical study was carried out using the SPSS program, version 20.0. For the comparison of percentages, the chi square test was used; for the means with homogeneous parameters, Student's t-test was used; and for the means with nonhomogeneous parameters, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used.

Results

The demographics of the patients are shown in Table 1. In both groups, the male-female distribution was not homogeneous, showing a clear male predominance. The reason for these differences is that the choice of the implant is made considering the bone quality observed on the preoperative radiograph and the femoral morphology. As a result, we use this implant in 52% of our patients, most of whom were male. The rest of demographic variables (BMI, age, diagnosis, and the size of implant used) did not show any differences between groups.

Table 1.

Demographics of the patients included in the study.

| ABG-II (n = 68) | ANATO (n = 66) | |

|---|---|---|

| Men/women | 47/21 | 56/10 |

| BMI | 28.1 kg/m2 | 32.8 kg/m2 |

| Age | 59 (SD: 10.8; min: 28, max: 76) | 57 (SD: 8.4; min: 36, max: 75) |

| Diagnosis | 100% osteoarthritis | 100% osteoarthritis |

| Size of the stem | 2: 2 patients | 3: 10 patients |

| 3: 13 patients | 4: 26 patients | |

| 4: 25 patients | 5: 15 patients | |

| 5: 17 patients | 6: 11 patients | |

| 6: 19 patients | 7: 4 patients | |

| 7: 2 patients | (100% with 7 degrees anteverted neck) |

The bone-mass evolution in both groups throughout the follow-up is shown in Table 2, Table 3. As osteoarthritic hips are almost always extrarotated and flexed, the preoperative values were not considered and the postoperative values were taken as a reference for monitoring BMD in the operated hip. Three months postoperatively, a generalized bone loss was observed in all the areas, being more marked in zone 7. This decrease in BMD was attributed to the surgical aggression of the rasps to the cancellous bone and endosteal blood supply and to a reduced physical activity in the postoperative period.

Table 2.

Changes in BMD in the ABG-II group.

| Gruen zones | Pre-Iqx | Post-Iqx Reference | 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 971 | 941 | 898 | 909 | 903 |

| Variation | −4.6% | −3.5% | −4.1% | ||

| SD | 193 | 180 | 193 | 191 | 199 |

| Max-min | 512-1498 | 492-1464 | 343-1198 | 396-1231 | 311-1299 |

| P | .097 | .403 | .795 | ||

| Zone 2 | 1877 | 1836 | 1821 | 1873 | 1842 |

| Variation | −0.9% | +2% | +0.4% | ||

| SD | 276 | 256 | 265 | 297 | 281 |

| Max-min | 1109-2365 | 1056-2207 | 1021-2256 | 1116-2372 | 1310-2650 |

| P | .854 | .447 | .297 | ||

| Zone 3 | 2187 | 2130 | 2063 | 2080 | 2090 |

| Variation | −3.2% | −2.4% | −1.9% | ||

| SD | 293 | 267 | 263 | 271 | 246 |

| Max-min | 1398-2432 | 1265-2327 | 1234-2598 | 1370-2689 | 1420-2657 |

| P | .263 | .583 | .803 | ||

| Zone 4 | 2107 | 2076 | 1985 | 1991 | 2002 |

| Variation | −4.4% | −4.1% | −3.6% | ||

| SD | 297 | 293 | 287 | 293 | 290 |

| Max-min | 1296-2710 | 1287-2675 | 1146-2479 | 1235-2570 | 1234-2607 |

| P | .142 | .130 | .356 | ||

| Zone 5 | 2172 | 2144 | 2048 | 2060 | 2115 |

| Variation | −4.5% | −4% | −1.3% | ||

| SD | 301 | 290 | 281 | 288 | 290 |

| Max-min | 1256-2654 | 1198-2594 | 1341-2527 | 1339-2517 | 1580-2678 |

| P | .105 | .130 | .482 | ||

| Zone 6 | 1802 | 1761 | 1749 | 1795 | 1812 |

| Variation | −0.7% | +1.9% | +3.1% | ||

| SD | 312 | 305 | 297 | 334 | 313 |

| Max-min | 1293-2278 | 1119-2070 | 1162-2093 | 1211-2365 | 1363-2425 |

| P | .741 | .236 | .131 | ||

| Zone 7 | 1476 | 1459 | 1274 | 1237 | 1202 |

| Variation | −12.7% | −15.3% | −17.7% | ||

| SD | 287 | 275 | 295 | 310 | 300 |

| Max-min | 719-1962 | 830-1680 | 536-1982 | 407-1994 | 690-1936 |

| P | .001 | .001 | .000 |

Pre-Ipx, pre-operative; Post-Iqx, post-operative (reference value).

Bold values indicates the statistical significance.

Table 3.

Changes in the BMD in the ANATO group.

| Gruen zones | Pre-Iqx | Post-Iqx Reference | 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 967 | 936 | 916 | 959 | 957 |

| Variation | −2.2% | +2.4% | +2.2% | ||

| SD | 200 | 164.9 | 178 | 202 | 212 |

| Max-min | 523-1617 | 611-1372 | 447-1427 | 419-1421 | 407-1424 |

| P | .239 | .400 | .673 | ||

| Zone 2 | 1913 | 1856 | 1809 | 1871 | 1895 |

| Variation | −2.6% | +0.9% | +2.1% | ||

| SD | 295 | 256 | 262 | 259 | 258 |

| Max-min | 1010-2315 | 1305-2396 | 1145-2459 | 1176-2335 | 1336-2713 |

| P | .228 | .930 | .318 | ||

| Zone 3 | 2210 | 2194 | 2085 | 2172 | 2177 |

| Variation | −5% | −1.1% | −0.8% | ||

| SD | 281 | 281 | 281 | 287 | 277 |

| Max-min | 1331-2467 | 1570-2839 | 1325-2659 | 1463-2872 | 1501-2790 |

| P | .061 | .266 | .249 | ||

| Zone 4 | 2122 | 2105 | 2030 | 2058 | 2080 |

| Variation | −3.6% | −2.7% | −1.2% | ||

| SD | 273 | 296 | 294 | 291 | 295 |

| Max-min | 1489-2750 | 1488-2835 | 1345-2659 | 1382-2607 | 1459-2791 |

| P | .131 | .119 | .165 | ||

| Zone 5 | 2161 | 2140 | 2042 | 2095 | 2106 |

| Variation | −4.6% | −2.1% | −1.6% | ||

| SD | 305 | 285 | 301 | 299 | 306 |

| Max-min | 1267-2692 | 1458-2647 | 1317-2593 | 1430-2619 | 1480-2739 |

| P | .101 | .125 | .168 | ||

| Zone 6 | 1780 | 1683 | 1649 | 1719 | 1774 |

| Variation | −2.1% | +2.1% | +5.2% | ||

| SD | 284 | 348 | 265 | 257 | 262 |

| Max-min | 1002-2248 | 1478-2374 | 879-2264 | 1201-2400 | 1234-2338 |

| P | .434 | .216 | .057 | ||

| Zone 7 | 1432 | 1400 | 1263 | 1313 | 1318 |

| Variation | −9.8% | −6.3% | −5.9% | ||

| SD | 201 | 212 | 218 | 258 | 248 |

| Max-min | 790-1717 | 1028-2045 | 491-1843 | 761-2002 | 670-1904 |

| P | .001 | .002 | .005 |

Pre-Ipx, pre-operative; Post-Iqx, post-operative (reference value).

Bold values indicates the statistical significance.

At the 6-month determination of the ABG-II group, a partial bone recovery was observed in zones 1-2-3-4-5-6, which was more evident—with positive remodeling—in zones 2 and 6. On the contrary, in zone 7, a moderate additional bone loss was observed, already statistically significant (decrease of 15.3%). One year postoperatively, this pattern of remodeling was stable, showing slight losses in zone 1 and distal areas, bone preservation in zones 2 and 6, and statistically significant proximal atrophy in zone 7 only (decrease of 17.7%).

The evolution of BMD at 6 months in the ANATO group also showed a recovery in all areas, with positive remodeling in zones 1, 2, and 6. In zone 7, a significant bone loss of 6.3% was observed. One year postoperatively, this pattern of remodeling was maintained, with minimal losses in distal areas; bone preservation in zones 1, 2, and 6; and a statistically significant decrease in bone mass of 5.9% in zone 7.

When analyzing the evolution of the BMD between implants at different times of the follow-up, no significant differences were observed in zones 2 to 6. Only in zone 1 of the ANATO group was a positive remodeling found from the 6th month, which did not exist in the ABG-II group. This finding was maintained at the end of the study, with a 2.2% increase in the ANATO group, compared with a 4.1% decrease in the ABG-II group, without achieving statistical significance. However, the changes in BMD in zone 7 between these implants were more pronounced and statistically significant at 6 and 12 months. In the ABG-II group, a 15.3% decrease in BMD was observed at 6 months, while in the ANATO group, the decrease was limited to 6.3% (P .001). At 12 months, the ABG-II group showed a decrease in BMD of 17.7%, in contrast to a decrease of 5.9% observed in the ANATO group (P .002).

When the changes in BMD of these stems were analyzed according to the gender, BMI, and age of the patients, we observed the same differences between stems. When the BMD differences between implants were studied according to the size used, size 4 was chosen as the cutoff point because from that size onward, the ANATO stem does not increase its length, unlike the ABG-II stem. The results obtained showed the same differences between stems.

Related to the evolution of BMD of the healthy hip, taken as a control, a variation in bone mass of −3.2% to +0.6% was observed. The BMD varied from −300 to +23.4 mgr/cm2 at the end of 12 months in the operated hip in contrast to the healthy hip, which ranged from −30.4 to +47.4 mgr/cm2. This difference was statistically significant only in area 7, in both groups. In the ABG-II group, the average decrease of BMD in area 7 at the end of the study was 274 mg/cm2 in the operated hip, but dropping 21 mg/cm2 in the control hip (P .001). In the ANATO group, the decrease of BMD in area 7 was 148 mg/cm2 in the operated hip and 13 mg/cm2 in the control hip (P .01).

The clinical results were similar between implants, obtaining a Merle D’Aubigne Postel (MDP) score of 7.5 (standard deviation [SD]: 1.27, min: 6, max: 12) preoperatively in the ABG-II group, which reached 16.8 (SD: 1.20, min: 12 max: 18) at the end of the first postoperative year. In the ANATO group, the preoperative clinical MDP score was 7.7 (SD: 1.18, min: 6, max: 11) which reached, 1 year postoperatively, 17.1 (SD: 1.21, min: 12, max: 18).

As for the radiological evolution, it was very frequent to find a light bony atrophy at the shoulder of the stem and some rounding at the level of the calcar in the ABG-II group at the end of the first year, without any other changes in middle and distal areas. These radiological changes coincided with the densitometric results. However, in most of the patients in the ANATO group, there was bone neoformation at the shoulder of the stems, and the remodeling changes at the calcar were less intense, all in accordance with the densitometric results (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Radiographic changes around the ABG-II showing rounding of the calcar and light atrophy at the greater trochanter. Immediate postoperative image on the left; 1-year postoperative image on the right.

Figure 3.

Radiographic changes around the ANATO stem showing a reduced calcar atrophy and bone apposition at the shoulder of the stem. Immediate postoperative image on the left; 1-year postoperative image on the right.

Discussion

The implantation of a femoral stem modifies the model of transmission of loads to the proximal femur, causing an adaptive bone remodeling of multifactorial origin. Among these factors, it is possible to distinguish those derived from the implant such as the design, size, alloy, and extension of the porous coating. To determine the influence of the implant on the femoral remodeling, it is necessary to minimize the variability in the surgical technique and in the postoperative recovery in a group of patients who, clinically, are very similar [[15], [16], [17]]. In addition, to accurately quantify those changes in BMD, it has been proven that dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry is a reliable method.

In densitometric studies with other implants, the variation of the BMD of the proximal femur after the implantation of an uncemented stem, at 3 and 6 months after the surgery, showed a decrease from 4% to 50% in the preoperative bone mass, depending on the implant and the surgical technique [18]. Among the main reasons for these losses, we can mention the partial load during the first weeks after the surgery and the immediate decrease of the bone stock after the femoral preparation with rasps, which may comprise up to 10% of the initial bone stock [19]. It is accepted that most of the remodeling is stabilized at the end of the first postoperative year, when the BMD reaches a plateau in all the areas around the stem, reflecting the changes of the new hip biomechanics, according to Wolff's law [20].

Studies performed with the ABG-I® and ABG-II® models show mild bone loss in zones 2 to 6 in both implants, already present at 3 and 6 months after implantation, with recovery at 12 months postoperatively. In both stems, more pronounced losses were observed in areas 1 and 7, but more intense in the ABG-I stem. The design of the ABG-II stem, with a widening of the metaphyseal anteroposterior diameter and with a shorter and smaller tail than the ABG-I, improved the pattern of load transmission to metaphyseal zones, explaining a lower bone loss in proximal areas [12] that ranged from 7% to 16%. The results of these anatomic models coincide with those observed in other similar anatomic designs, which share the same proximal fixation philosophy. These implants seek a close match of the stem with the proximal endosteal geometry, and stability is achieved through metaphyseal fill and distal curve. As a result, they showed decreases of 9%-23% BMD in the proximal femur at the end of the first postoperative year. With other designs, some variability has been observed in the remodeling of the proximal femur at 12 months of evolution; thus, single-wedge stems, with 3-point fixation along the stem length, cause a decrease of 12%-38%. With tapered stems, drops of 26%-31% have been documented. With rectangular, tapered stems, which obtain 3-point fixation in the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction and proximal part of the diaphysis, the decrease was between 7% and 30%. With custom-made stems, the proximal atrophy was between 7% and 24% [21,22]. With short stems, a 12.9% decrease in BMD was observed in the femoral calcar with the Metha stem (Aesculap Orthopaedics, Germany), 18%-29% with the CFP stem (Waldemar Link, Germany), and 6%-15% with the Nanos stem (Smith & Nephew, England). With the Mayo stem (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN,), the proximal atrophy reaches 14%-17%, and with the Proxima (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN, it oscillates between 8% and 14% [[23], [24], [25]].

Analyzing the role that design differences between these implants can cause in the remodeling, it can be suggested that, in coincidence with other authors [26], the increased thickness and porosity of the biological coating of the ANATO stem provides stronger, more reliable osseointegration of superior quality and quantity than the ABG-II stem. This improved fixation of the stem favors the pattern of load transmission to be more similar to the physiological load pattern of the nonoperated femur, minimizes the atrophy at the proximal femur, and favors a positive remodeling. Thus, greater bone preservation in the proximal femur could theoretically reduce the risk of periprosthetic fractures and provide an improved bone stock in case of implant revision.

This study has some limitations to consider. First, in both groups, there are more men than women. Middle-aged men usually have femurs with good bone quality, but this quality was less frequent in the women received in our practice, so the indication for uncemented anatomic implants was lower in female patients. Thus, the results obtained for the total group cannot be extrapolated to the group of female patients. The same happens with age. In both groups, the patients are relatively young, and this pattern of remodeling in older patients cannot be guaranteed. The follow-up of our study is relatively short, and we can expect changes attributable to late remodeling in the longer term. However, it is accepted that most of the adaptative changes of the femur occur during the first postoperative year. Finally, the alloy of the implants was different, but in both cases, the rigidity of the implant exceeds 3 times the rigidity of the cortical bone (20 GPa) and the small difference had no influence on the pattern of remodeling [12].

In conclusion, both anatomic stems achieve an efficient transmission of loads at the metaphyseal level that creates sufficient stimulus for bone preservation. However, the greater porosity of the biological coating of the ANATO stem obtains a better bone fit of the implant at the proximal level. This favors bone preservation at the proximal level, minimizing atrophy due to stress shielding. Theoretically, this greater bone preservation can favor long-term implant fixation and decrease the rate of revisions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Huiskes R., Weinans H., Dalstra M. Adaptative bone remodelling and biomechanical design considerations for noncemented total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1989;12:1255. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19890901-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthall L., Bobyn J.D., Tanzer M. Bone densitometry: influence of prosthetic design and hydroxyapatite coating on regional adaptative bone remodeling. Int Orthop. 1999;23:325. doi: 10.1007/s002640050383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbons C., Davis A., Olearnik H. Periprosthetic bone mineral density changes with femoral components of different design philosophy. Int Orthop. 2001;25:89. doi: 10.1007/s002640100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sychter C.J., Engh C.A. The influence of clinical factor on periprosthetic bone remodeling. Clin Orthop. 1996;322:285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engh C.A., Jr., Mc Auley J.R., Sychterz J.P., Sacco C.J., Engh C.A., Sr. The accuracy and reproducibility of radiographic assessment of stress-shielding. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A:1414. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroger H., Miettinen H., Arnala I., Koski E., Rushton N., Suomalainen O. Evaluation of periprosthetic bone using dual Energy X-ray absorptiometry: precision of the method and effect of operation on bone mineral density. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(10):1526. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt R., Nowak T.E., Mueller L., Pitto R. Osteodensitometry after total hip replacement with uncemented Taper-design stem. Int Orthop. 2004;28(2):74. doi: 10.1007/s00264-003-0519-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirata Y., Inaba Y., Kobayashi N., Ike H., Fujimaki H., Saito T. Comparison of mechanical stresses and change in bone mineral density between two types of femoral implant using finite element analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(10):1731. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera A., Canales V., Anderson J., García-Araujo C., Murcia-Mazón A., Tonino A.J. Seven to 10 years follow-up of an anatomic hip prosthesis: an international study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:129. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000128973.73132.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonino A.J., Rahmy A.I. The hydroxyapatite-ABG hip system: 5 to 7 years results from an international multicenter study. The International ABG Study Group. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(3):274. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bidar R., Kouyoumdjian P., Munini E., Asencio G. Long-term results of the ABG-1 hydroxyapatite coated total hip arthroplasty: analysis of 111 cases with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(8):579. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gracia L., Ibarz E., Puértolas S. Study of bone remodelling of two models of cementless antomic stems by means of DEXA and finite elements. Biomed Eng Online. 2010;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Subías J., Panisello J.J., Mateo-Agudo J., Lillo-Adan M., Herrera A. Adaptive bone remodeling with new design of the ABG stem. Densitometric study. J Clin Densitom. 2019;22(3):351. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panisello J.J., Canales V., Herrero L., Herrera A., Mateo J., Caballero M.J. Changes in periprosthetic bone remodelling after redesigning an anatomic cementless stem. Int Orthop. 2009;33(2):373. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0501-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martini F., Lebherz C., Mayer F., Leichtle U., Kremling E., Sell S. Precision of the measurements of periprosthetic bone mineral density around hips with a custom-made femoral stem. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1065. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b7.9791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellman E.J., Capello W.N., Feinberg J.R. Omnifit cementless total hip arthroplasty: a 10-years average follow up. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;364:164. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199907000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun A., Papp J., Reiter A. The periprosthetic bone remodelling process signs of vital bone reaction. Int Orthop. 2003;27(Suppl 1):7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knutsen A.R., Lau N., Longjohn D.B., Ebramzadeh E., Sangiorgio S. Periprosthetic femoral bone loss in total hip arthroplasty: systematic analysis of the effect of stem design. Hip Int. 2017;27(1):26. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riviere Ch, Grappiolo G., Engh Ch. Long-term bone remodeling around “legendary” cementless femoral stems. EFFORT Open Rev. 2018;3:45. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Boer F., Sariali E. Comparison of anatomic vs straight femoral stem design in total hip replacement-femoral canal fill in vivo. Hip Int. 2017;27(3):241. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theis J.C., Beadel G. Changes in proximal femoral bone mineral density around a hydroxyapatite-coated hip joint arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2003;11:48. doi: 10.1177/230949900301100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grochola L.F., Haberman B., Mastrodomenico N., Kurth A. Comparison of periprosthetic bone remodelling after implantation of anatomic and straight stem prosthesis in total hip arthroplasty. Ach Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:383. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inaba Y., Kobayashi N., Oba M., Ike H., Kubota S., Saito T. Difference in postoperative periprosthetic bone mineral density changes between 3 major designs of uncemented stems: a 3 year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1826. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan S.G., Li D., Yin S., Hua X., Tang J., Schmidutz F. Periprosthetic bone remodeling of short cementless femoral stems in primary total hip arthroplasty. Medicine. 2017;96(47):e8806. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y.H., Park J.W., Kim J.S., Kang J.S. Long term results and bone remodeling after THA with a short, metaphyseal-fitting anatomic cementless stem. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:943. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3354-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira A., Aslanian T., Dalin T., Picaud J. Ceramic bearings with bilayer coating in cementless total hip arthroplasty. A safe solution. A retrospective study of one hundred and twenty six cases with more than ten years’ follow-up. Int Orthop. 2017;41(5):893. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.