Abstract

Objective

To determine if personal health of spine surgeons worldwide influences perceptions, healthcare delivery, and decision-making during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed by distributing a multidimensional survey to spine surgeons worldwide. Questions addressed demographics, impacts and perceptions of COVID-19, and the presence of surgeon comorbidities, which included cancer, cardiac disease, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, respiratory illness, renal disease, and current tobacco use. Multivariate analysis was performed to identify specific comorbidities that influenced various impact measures.

Results

Across 7 global regions, 36.8% out of 902 respondents reported a comorbidity, of which hypertension (21.9%) and obesity (15.6%) were the most common. Multivariate analysis noted tobacco users were more likely to continue performing elective surgery during the pandemic (odds ratio [OR], 2.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.46–4.72; p = 0.001) and were less likely to utilize telecommunication (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.31–0.86; p = 0.011), whereas those with hypertension were less likely to warn their patients should the surgeon become infected with COVID-19 (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37–0.91; p = 0.017). Clinicians with multiple comorbidities were more likely to cite personal health as a current stressor (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.07–1.63; p = 0.009) and perceived their hospital’s management unfavorably (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60–0.91; p = 0.005).

Conclusion

This is the first study to have mapped global variations of personal health of spine surgeons, key in the development for future wellness and patient management initiatives. This study underscored that spine surgeons worldwide are not immune to comorbidities, and their personal health influences various perceptions, healthcare delivery, and decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Spine, Surgeon, Health, Burnout

INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected both patients and healthcare providers around the world. The current healthcare landscape has changed, and healthcare delivery has molded to provide care to patients who otherwise would not receive it during these times [1,2]. However, despite our greatest efforts, the effects of COVID-19 have persisted, and the spine surgery community is not exempt. A recent study by Louie et al. [3] revealed the worldwide impact of COVID-19 on clinical practice, income, personal life, research, resident and fellow training, and anxiety levels among spine surgeons.

While many physicians have halted their surgical practices in lieu of restrictions on elective surgeries and face-to-face encounters, thousands of physicians, including spine surgeons, have found themselves at the front-line managing patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) and medical wards [4,5]. Worried that they themselves may become infected with COVID-19, physicians and other healthcare providers have become filled with fear. COVID-19 specifically affects the respiratory system, and can induce a pneumonia and chronic fibrosis with long-term sequelae, and may even lead to death [6]. Contrary to popular belief, physicians are fraught with cardiopulmonary and other comorbidities that increase the risk of complications from COVID-19 [7].

Several studies have noted physician burnout and mental health consequences [8-10]. However, there is limited evidence highlighting the physical health of spine surgeons. As physicians are finding themselves treating patients with COVID-19, the importance of physician health becomes even more relevant. Furthermore, as spine practices slowly return to normalcy, there is little understanding of how the health of spine surgeons will be affected, and how such health status influences spine surgery healthcare delivery in the age of COVID-19. Therefore, the authors aimed to examine the health disparities of spine surgeons around the world, and how their health influences their perspectives, healthcare delivery, and decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Survey Design and Content

A survey, known as the AO Spine COVID-19 and Spine Surgeon Global Impact Survey, was developed to obtain representation from various global regions. Both multiple-choice and free-text questions were created based on input from multiple authors utilizing a Delphi method as previously reported [3]. Questions were structured to capture relevant components including: demographics, perceptions related to COVID-19, and the associated financial impacts, as well as future predictions. Comorbidities surveyed included cancer, cardiac disease, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, respiratory illness, renal disease, and current tobacco use.

2. Survey Distribution

Utilizing a secure email distribution method, the 73-item survey was administered to all AO Spine members who agreed to receive surveys, approximately 3,805 individuals. The survey recipients were provided 9 days to complete the survey (March 27, 2020 to April 4, 2020). Participants were notified of their willingness to contribute and that the information gained would be confidentially analyzed and published. Respondents were able to omit responses, and several questions allowed for multiple responses, altering the total number of responses to be less than or more than the total respondents.

3. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with Stata ver. 13.1 (StataCorp LC, College Station, TX, USA) with graphical representation of comorbidity distribution using RStudio v1.2.1335 (RStudio Inc, Boston, MA, USA). Survey findings were collected for each respondent and summarized using count data and percentage calculations. Medical comorbidities were then tabulated for each respondent, allowing stratification of the cohort into groups based upon the number of concomitant diagnoses (1, 2, 3, or more comorbidities, and no comorbidities). All comorbidity findings were then assessed using a combination of chi-square and Fisher exact tests to determine relevance with other collected survey responses.

Multivariate models were then derived to further assess the significance of comorbidities, controlling for age, sex, specialty, and practice type. All model covariates were selected and agreed upon by the senior coauthors due to the potential for confounding with assessed survey responses and comorbidity status. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for binary outcome survey queries while multivariate ordinal logistic regression was performed for questions including ordinal scales. Odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values were then calculated for each covariate and used to further assess comorbidity significance. ORs greater than 1 suggest that the assessed variable increases the likelihood of a particular response, whereas those less than 1 suggest a lower response. ORs equal to 1 indicate that the variable has no effect on either increasing or decreasing the likelihood of a given answer. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and p-values were assessed for precision.

RESULTS

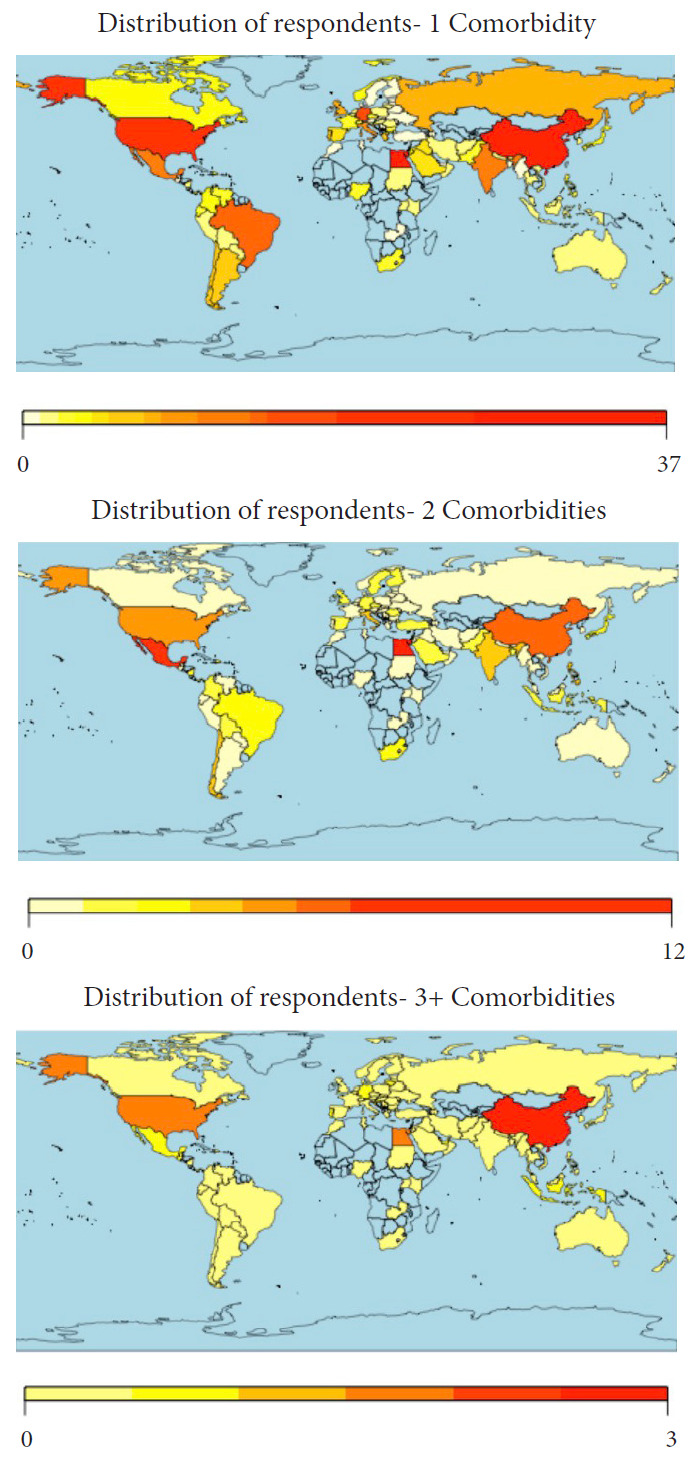

Of all spine surgeons surveyed, 902 participated, providing distinct data across 91 countries and 7 global regions affected by COVID-19. Detailed demographic results of the surveyed cohort have been previously published and reported by Louie et al. [3] Specifically, Table 1 presents the significant differences in age, specialty, and hospital practice type between regions. Roughly 36.8% of surgeons have at least 1 medical comorbidity, with hypertension (21.9%) and obesity (15.6%) being the most commonly reported. Further, some surgeons suffer from additional medical burden, with 10.2% and 2.6% reporting 2 and 3 or more comorbidities, respectively. Overall, despite these findings, most survey respondents are currently healthy (62.8%). There was also a significant difference in the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, tobacco use, diabetes, and the number of comorbidities between regions (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Medical comorbidity demographics

| Variable | Overall |

Africa |

Asia |

Australia |

Europe |

Middle East |

North America |

South America/Latin America |

p-value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 25–34 | 127 | 14.4 | 5 | 11.4 | 28 | 13.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 29 | 12.0 | 16 | 20.8 | 28 | 18.5 | 21 | 14.5 | 0.017* | |

| 35–44 | 338 | 38.4 | 21 | 47.7 | 66 | 31.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 97 | 40.1 | 25 | 32.5 | 63 | 41.7 | 65 | 44.8 | ||

| 45–54 | 241 | 27.4 | 11 | 25.0 | 73 | 34.3 | 3 | 37.5 | 66 | 27.3 | 22 | 28.6 | 32 | 21.2 | 34 | 23.5 | ||

| 55–64 | 149 | 16.9 | 5 | 11.4 | 44 | 20.7 | 4 | 50.0 | 42 | 17.4 | 14 | 18.2 | 20 | 13.3 | 20 | 13.8 | ||

| 65+ | 25 | 2.8 | 2 | 4.6 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 5.3 | 5 | 3.5 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 812 | 93.8 | 42 | 100.0 | 203 | 95.8 | 8 | 100.0 | 213 | 91.0 | 74 | 96.1 | 140 | 94.0 | 132 | 91.7 | 0.144 | |

| Female | 54 | 6.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 21 | 9.0 | 3 | 3.9 | 9 | 6.0 | 12 | 8.3 | ||

| Specialty | ||||||||||||||||||

| Orthopaedics | 625 | 71 | 35 | 79.6 | 178 | 83.6 | 5 | 62.5 | 151 | 62.4 | 54 | 71.1 | 115 | 75.7 | 87 | 60.0 | < 0.001* | |

| Neurosurgery | 244 | 27.7 | 8 | 18.2 | 36 | 16.9 | 2 | 25.0 | 85 | 35.1 | 19 | 25.0 | 38 | 25.0 | 56 | 38.6 | ||

| Trauma | 102 | 11.6 | 5 | 11.4 | 18 | 8.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 54 | 22.3 | 9 | 11.8 | 2 | 1.3 | 14 | 9.7 | ||

| Other | 52 | 5.9 | 2 | 4.6 | 13 | 6.1 | 2 | 25.0 | 18 | 7.4 | 8 | 10.5 | 4 | 2.6 | 5 | 3.5 | ||

| Practice type | ||||||||||||||||||

| Academic/private combined | 198 | 22.5 | 13 | 29.6 | 29 | 13.6 | 4 | 50.0 | 47 | 19.4 | 28 | 36.4 | 23 | 15.1 | 54 | 37.2 | < 0.001* | |

| Academic | 400 | 45.4 | 20 | 45.5 | 127 | 59.6 | 1 | 12.5 | 115 | 47.5 | 23 | 29.9 | 91 | 59.9 | 23 | 15.9 | ||

| Private | 142 | 16.1 | 7 | 15.9 | 26 | 12.2 | 1 | 12.5 | 20 | 8.3 | 15 | 19.5 | 30 | 19.7 | 43 | 29.7 | ||

| Public/local hospital | 137 | 15.6 | 4 | 9.1 | 30 | 14.1 | 2 | 25.0 | 59 | 24.4 | 11 | 14.3 | 7 | 4.6 | 24 | 16.6 | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Obesity | 102 | 15.6 | 7 | 24.1 | 23 | 15.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 26 | 13.9 | 16 | 31.4 | 8 | 6.3 | 22 | 20.8 | < 0.001* | |

| Hypertension | 155 | 21.9 | 10 | 31.3 | 36 | 22.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 34 | 17.4 | 18 | 34.0 | 20 | 14.3 | 37 | 30.6 | 0.003* | |

| Current tobacco use | 75 | 11.9 | 2 | 8.3 | 32 | 20.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 12.5 | 7 | 16.7 | 2 | 1.6 | 9 | 9.7 | < 0.001* | |

| Respiratory illness | 35 | 6.0 | 3 | 12.0 | 5 | 3.9 | 1 | 14.3 | 9 | 5.3 | 2 | 5.4 | 6 | 4.8 | 9 | 9.7 | 0.390 | |

| Renal disease | 5 | 0.9 | 1 | 4.4 | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.541 | |

| Cancer | 4 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.878 | |

| Cardiac disease | 25 | 4.3 | 3 | 12.0 | 4 | 3.1 | 1 | 14.3 | 7 | 4.2 | 2 | 5.4 | 3 | 2.4 | 5 | 5.6 | 0.300 | |

| Diabetes | 44 | 7.4 | 5 | 18.5 | 19 | 13.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.8 | 9 | 20.5 | 2 | 1.6 | 6 | 6.7 | < 0.001* | |

| 1 Comorbidity | 250 | 31.1 | 15 | 40.5 | 68 | 35.2 | 2 | 25.0 | 65 | 28.8 | 31 | 47.0 | 24 | 16.7 | 45 | 34.9 | < 0.001* | |

| 2 Comorbidities | 63 | 10.2 | 6 | 21.4 | 15 | 10.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 6.9 | 10 | 22.2 | 6 | 4.8 | 14 | 14.3 | 0.003* | |

| 3+ Comorbidities | 15 | 2.6 | 1 | 4.4 | 5 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.4 | 1 | 2.8 | 2 | 1.6 | 2 | 2.3 | 0.945 | |

| No comorbidities | 553 | 62.8 | 22 | 50.0 | 125 | 58.7 | 6 | 75.0 | 161 | 66.5 | 35 | 45.5 | 120 | 79.0 | 84 | 57.9 | < 0.001* | |

Calculation of p-values was performed using a combination of chi-square and Fisher exact tests.

p < 0.05, statistical significance.

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of spine surgeons reporting medical comorbidities. Coloring of maps based on number of respondents with specified comorbidities.

When compared to healthy individuals, surgeons with specific comorbidities demonstrated significant variations in reported perceptions and stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). Surgeons suffering from obesity, hypertension, cardiac disease, and 1 or 2 comorbidities had significant concern about their personal health, whereas those diagnosed with cancer and respiratory illnesses were more concerned with return to nonessential activities and economic issues, respectively. Respondents with no comorbidities, hypertension, or 1 comorbidity were also more concerned with the timeline to resume clinical practice. A diagnosis of renal disease did not influence COVID-19 perceptions. Those with 3 or more comorbidities had the greatest influence on being personally diagnosed with COVID-19. Lastly, a diagnosis of cancer was associated with being quarantined (p = 0.007), though comorbidities otherwise had no association with institutional or governmental perceptions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medical comorbidities and association with COVID-19 perceptions

| Variable | Obesity |

Hypertension |

Current tobacco use |

Respiratory illness |

Renal disease |

Cancer |

Cardiac disease |

Diabetes |

1 Comorbidity |

2 Comorbidities |

3+ Comorbidities |

No comorbidities |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | ||

| COVID-19 diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Know someone diagnosed | 41 | 14.2 | 0.519 | 72 | 22.5 | 0.469 | 35 | 12.4 | 0.356 | 16 | 6.1 | 0.562 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.916 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.916 | 9 | 3.5 | 0.621 | 15 | 5.7 | 0.345 | 112 | 31.1 | 0.573 | 26 | 9.5 | 0.517 | 6 | 2.4 | 0.798 | 248 | 63.3 | 0.792 | |

| Personally diagnosed | 3 | 37.5 | 0.079 | 1 | 16.7 | 0.781 | 1 | 16.7 | 0.665 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.592 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.892 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.892 | 1 | 16.7 | 0.116 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.547 | 3 | 37.5 | 0.647 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.448 | 1 | 16.7 | 0.020* | 5 | 55.6 | 0.608 | |

| COVID-19 testing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Know how to get tested | 74 | 14.2 | 0.067 | 122 | 21.4 | 0.943 | 55 | 11.0 | 0.626 | 26 | 5.5 | 0.927 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.210 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.526 | 17 | 3.7 | 0.245 | 33 | 6.9 | 0.824 | 199 | 30.8 | 0.532 | 45 | 9.2 | 0.038* | 10 | 2.2 | 0.548 | 447 | 63.8 | 0.699 | |

| Personally tested | 6 | 13.0 | 0.641 | 7 | 14.9 | 0.254 | 1 | 2.4 | 0.065 | 3 | 7.0 | 0.648 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.688 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.688 | 2 | 4.8 | 0.824 | 2 | 4.8 | 0.590 | 13 | 24.5 | 0.339 | 4 | 9.1 | 0.776 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.307 | 40 | 70.2 | 0.277 | |

| Reason for testing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Direct contact with COVID-19 positive patient | 4 | 30.8 | 0.448 | 6 | 27.3 | 0.210 | 1 | 10.0 | 0.050 | 1 | 25.0 | 0.503 | - | - | - | 1 | 2.7 | 0.242 | 3 | 7.7 | 0.696 | 2 | 5.3 | 0.492 | 8 | 18.2 | 0.013* | 5 | 12.2 | 0.820 | - | - | - | 36 | 73.5 | 0.045 | |

| Prophylactic | 2 | 15.4 | 0.300 | 1 | 4.6 | 0.679 | 2 | 20.0 | 0.158 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.585 | - | - | - | 0 | 0.0 | 0.784 | 1 | 14.3 | 0.387 | 1 | 14.3 | 0.481 | 5 | 45.5 | 0.328 | 1 | 14.3 | 0.799 | - | - | - | 6 | 50.0 | 0.357 | |

| Demonstrated symptoms | 6 | 46.2 | 0.918 | 11 | 50.0 | 0.846 | 6 | 60.0 | 0.461 | 3 | 75.0 | 0.285 | - | - | - | 0 | 0.0 | 0.342 | 2 | 4.7 | 0.496 | 2 | 4.7 | 0.330 | 24 | 36.9 | 0.252 | 3 | 6.8 | 0.201 | - | - | - | 41 | 60.3 | 0.629 | |

| Ask to be tested | 1 | 7.7 | 0.473 | 4 | 18.2 | 0.012* | 1 | 10.0 | 0.329 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.704 | - | - | - | 0 | 0.0 | 0.849 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.642 | 2 | 40.0 | 0.005 | 4 | 57.1 | 0.148 | 2 | 40.0 | 0.038* | - | - | - | 3 | 33.3 | 0.063 | |

| Current stressors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal health | 49 | 50.0 | 0.035* | 78 | 53.1 | 0.002* | 27 | 39.7 | 0.866 | 15 | 48.4 | 0.280 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.742 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.076 | 16 | 69.6 | 0.003* | 17 | 7.6 | 0.541 | 110 | 47.0 | 0.030* | 37 | 59.7 | 0.001* | 5 | 38.5 | 0.989 | 206 | 57.5 | 0.003* | |

| Family health | 76 | 77.6 | 0.597 | 115 | 78.2 | 0.425 | 50 | 73.5 | 0.786 | 25 | 80.7 | 0.482 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.415 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.415 | 20 | 87.0 | 0.193 | 28 | 7.2 | 0.908 | 184 | 78.6 | 0.283 | 46 | 74.2 | 0.883 | 10 | 76.9 | 0.877 | 362 | 62.6 | 0.868 | |

| Community health | 36 | 36.7 | 0.120 | 61 | 41.5 | 0.422 | 34 | 50.0 | 0.456 | 9 | 29.0 | 0.078 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.892 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.892 | 13 | 56.5 | 0.287 | 22 | 8.4 | 0.176 | 92 | 39.3 | 0.129 | 30 | 48.4 | 0.635 | 7 | 53.9 | 0.537 | 241 | 65.1 | 0.328 | |

| Hospital capacity | 44 | 44.9 | 0.573 | 65 | 44.2 | 0.605 | 26 | 38.2 | 0.570 | 11 | 35.5 | 0.485 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.231 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.815 | 8 | 34.8 | 0.501 | 11 | 4.7 | 0.095 | 99 | 42.3 | 0.904 | 27 | 43.6 | 0.796 | 3 | 23.1 | 0.175 | 223 | 63.4 | 0.979 | |

| Timeline to resume clinical practice | 41 | 41.8 | 0.218 | 55 | 37.4 | 0.016* | 29 | 42.7 | 0.355 | 11 | 35.5 | 0.156 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.170 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.147 | 10 | 43.5 | 0.631 | 14 | 5.1 | 0.125 | 88 | 37.6 | 0.005* | 23 | 37.1 | 0.086 | 8 | 61.5 | 0.356 | 259 | 68.5 | 0.005* | |

| Government/leadership | 19 | 19.4 | 0.988 | 22 | 15.0 | 0.227 | 13 | 19.1 | 0.968 | 7 | 22.6 | 0.656 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.489 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.489 | 6 | 26.1 | 0.424 | 6 | 5.5 | 0.545 | 36 | 15.4 | 0.192 | 12 | 19.4 | 0.995 | 3 | 23.1 | 0.735 | 103 | 66.9 | 0.308 | |

| Return to nonessential activities | 11 | 11.2 | 0.450 | 22 | 15.0 | 0.784 | 10 | 14.7 | 0.888 | 4 | 12.9 | 0.855 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.567 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.001* | 3 | 13.0 | 0.889 | 4 | 5.1 | 0.505 | 31 | 13.3 | 0.761 | 7 | 11.3 | 0.548 | 3 | 23.1 | 0.359 | 75 | 64.7 | 0.745 | |

| Economic issues | 43 | 43.9 | 0.513 | 62 | 42.2 | 0.255 | 29 | 42.7 | 0.453 | 21 | 67.7 | 0.028* | 0 | 0.0 | 0.180 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.943 | 13 | 56.5 | 0.395 | 13 | 4.9 | 0.088 | 95 | 40.6 | 0.079 | 32 | 51.6 | 0.536 | 5 | 38.5 | 0.520 | 253 | 65.7 | 0.182 | |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 0.222 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.135 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.309 | 1 | 3.2 | 0.456 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.861 | 1 | 50.0 | < 0.001* | 0 | 0.0 | 0.554 | 1 | 11.1 | 0.607 | 3 | 1.3 | 0.814 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.331 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.656 | 8 | 72.7 | 0.514 | |

| Media perceptions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accurate coverage | 35 | 35.7 | 0.041* | 73 | 50.0 | 0.394 | 35 | 51.5 | 0.881 | 13 | 41.9 | 0.416 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.775 | 1 | 100.0 | 0.590 | 9 | 39.1 | 0.601 | 18 | 6.5 | 0.691 | 119 | 51.3 | 0.052 | 26 | 41.9 | 0.595 | 3 | 23.1 | 0.180 | 259 | 63.6 | 0.181 | |

| Excessive coverage | 53 | 54.1 | 54 | 37.0 | 21 | 30.9 | 14 | 45.2 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 43.5 | 12 | 6.3 | 88 | 37.9 | 23 | 37.1 | 7 | 53.9 | 180 | 60.4 | |||||||||||||

| Not enough coverage | 18 | 18.4 | 19 | 13.0 | 12 | 17.7 | 4 | 12.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 17.4 | 9 | 8.7 | 25 | 10.8 | 13 | 21.0 | 3 | 23.1 | 94 | 69.6 | |||||||||||||

| Current media sources | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International news - internet | 22 | 25.0 | 0.663 | 30 | 21.0 | 0.023* | 20 | 31.3 | 0.693 | 6 | 20.0 | 0.971 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.856 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.018* | 1 | 4.6 | 0.082 | 9 | 6.4 | 0.110 | 58 | 27.1 | 0.496 | 10 | 16.4 | 0.005* | 3 | 23.1 | 0.277 | 131 | 64.9 | 0.238 | |

| International news - television | 8 | 9.1 | 17 | 11.9 | 5 | 7.8 | 3 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 3 | 6.4 | 17 | 7.9 | 11 | 18.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 44 | 61.1 | |||||||||||||

| National/local news - internet | 25 | 28.4 | 29 | 20.3 | 20 | 31.3 | 11 | 36.7 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 27.3 | 6 | 3.8 | 55 | 25.7 | 11 | 18.0 | 5 | 38.5 | 153 | 68.3 | |||||||||||||

| National/local news - television | 21 | 23.9 | 43 | 30.1 | 9 | 14.1 | 6 | 20.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 40.9 | 9 | 8.0 | 49 | 22.9 | 23 | 37.7 | 1 | 7.7 | 104 | 58.8 | |||||||||||||

| Newspaper | 1 | 1.1 | 6 | 4.2 | 2 | 3.1 | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 9 | 4.2 | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 7.7 | 17 | 60.7 | |||||||||||||

| Social media | 11 | 12.5 | 18 | 12.6 | 8 | 12.5 | 3 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 21 | 15.3 | 26 | 12.2 | 5 | 8.2 | 3 | 23.1 | 41 | 54.7 | |||||||||||||

| Quarantined | 21 | 15.7 | 0.945 | 41.0 | 26.6 | 0.068 | 21 | 15.7 | 0.945 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 0.144 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.319 | 2 | 1.7 | 0.007* | 3 | 2.6 | 0.350 | 12 | 9.6 | 0.159 | 60 | 34.7 | 0.149 | 16 | 12.4 | 0.396 | 4 | 3.4 | 0.402 | 113 | 58.6 | 0.101 | |

| Perception of hospital effectiveness | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acceptable/appropriate | 46 | 52.3 | 0.216 | 86 | 60.1 | 0.570 | 31 | 48.4 | 0.188 | 18 | 60.0 | 0.283 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.141 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.750 | 12 | 54.6 | 0.430 | 24 | 7.3 | 0.406 | 136 | 63.6 | 0.758 | 31 | 50.8 | 0.322 | 6 | 46.2 | 0.464 | 304 | 63.7 | 0.772 | |

| Excessive/unnecessary | 3 | 3.4 | 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 3.1 | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 7.7 | 12 | 70.6 | |||||||||||||

| Disarray/disorganized | 13 | 14.8 | 10 | 7.0 | 9 | 14.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 18.2 | 1 | 2.3 | 16 | 7.5 | 7 | 11.5 | 2 | 15.4 | 43 | 63.2 | |||||||||||||

| Not enough action | 26 | 29.6 | 45 | 31.5 | 22 | 34.4 | 11 | 36.7 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 27.3 | 12 | 8.5 | 59 | 27.6 | 22 | 36.1 | 4 | 30.8 | 130 | 60.5 | |||||||||||||

| Perception of government effectiveness | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acceptable/appropriate | 53 | 60.2 | 0.711 | 79 | 55.2 | 0.627 | 37 | 57.8 | 0.849 | 21 | 70.0 | 0.445 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.899 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.673 | 14 | 63.6 | 0.179 | 23 | 7.7 | 0.476 | 143 | 66.8 | 0.064 | 29 | 47.5 | 0.438 | 7 | 53.9 | 0.156 | 277 | 60.8 | 0.409 | |

| Excessive/unnecessary | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | 2.8 | 3 | 4.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.9 | 2 | 3.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 70.0 | |||||||||||||

| Disarray/disorganized | 11 | 12.5 | 22 | 15.4 | 7 | 10.9 | 3 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 22.7 | 2 | 3.5 | 22 | 10.3 | 6 | 9.8 | 4 | 30.8 | 56 | 63.6 | |||||||||||||

| Not enough action | 23 | 26.1 | 38 | 26.6 | 17 | 26.6 | 6 | 20.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 12 | 7.7 | 45 | 21.0 | 24 | 39.3 | 2 | 15.4 | 144 | 67.0 | |||||||||||||

Calculation of p-values was performed using a combination of chi-square and Fisher exact tests.

Comparisons are made between respondents with comorbidities and healthy individuals. Clinicians with no comorbidities were compared to those with one or more comorbidity. All percentages are calculated based upon the total number of responses received for each question and comorbidity combination.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

p < 0.05, statistical significance.

There was also significant variation in those performing elective cases during the COVID-19 pandemic when comparing practitioners with and without comorbidities (any comorbidity: p = 0.006; 1 comorbidity: p = 0.003) (Table 3). There was also significant variation in respondents with diabetes and how they would warn their patients if they tested positive for COVID-19 (p = 0.026). Further, when compared to healthy clinicians, those with comorbidities (p = 0.031) or hypertension reported significant differences on impacted research productivity. Finally, regarding the implementation of specific surgical precaution, those with one or more comorbidities (any comorbidity: p = 0.014; 1 comorbidity: p = 0.033), hypertension (p = 0.020), tobacco use (p = 0.030), or cardiac disease (p = 0.049) had significant variation in whether they would be absent during patient intubation/extubation, while those with 1 comorbidity varied in their opinions to proceed with standard precautions (p = 0.036). There was no significant association between medical comorbidities and additional personal protective equipment (PPE) use during surgery.

Table 3.

Medical comorbidities and association with clinical practice

| Variable | Obesity |

Hypertension |

Current tobacco use |

Respiratory illness |

Renal disease |

Cancer |

Cardiac disease |

Diabetes |

1 Comorbidity |

2 Comorbidities |

3+ Comorbidities |

No comorbidities |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | ||

| Still performing elective surgery | 18 | 18.6 | 0.348 | 33 | 24.5 | 0.500 | 21 | 21.0 | 0.001* | 1 | 1.3 | 0.060 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.543 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.543 | 4 | 4.8 | 0.749 | 10 | 11.2 | 0.087 | 56 | 41.5 | 0.003* | 11 | 12.2 | 0.670 | 3 | 3.7 | 0.468 | 79 | 53.0 | 0.006* | |

| Essential/emergency spine surgery | 74 | 14.2 | 0.055 | 123 | 21.5 | 0.308 | 59 | 11.6 | 0.841 | 25 | 5.3 | 0.387 | 2 | 0.4 | 0.611 | 2 | 0.4 | 0.611 | 18 | 3.9 | 0.336 | 35 | 7.2 | 0.504 | 187 | 29.4 | 0.141 | 52 | 10.4 | 0.448 | 12 | 2.6 | 0.674 | 449 | 64.1 | 0.154 | |

| Impact on clinical time spent | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Increased | 3 | 3.3 | 0.283 | 10 | 6.9 | 0.889 | 5 | 7.6 | 0.865 | 2 | 6.5 | 0.829 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.832 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.832 | 1 | 4.6 | 0.809 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.181 | 12 | 5.4 | 0.587 | 3 | 4.8 | 0.878 | 1 | 7.7 | 0.492 | 30 | 65.2 | 0.703 | |

| Decreased | 76 | 82.6 | 122 | 84.1 | 55 | 83.3 | 25 | 80.7 | 2 | 100.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 18 | 81.8 | 36 | 7.8 | 183 | 82.4 | 52 | 83.9 | 12 | 92.3 | 428 | 63.4 | |||||||||||||

| Stayed the same | 13 | 14.1 | 13 | 9.0 | 6 | 9.1 | 4 | 12.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 2 | 3.9 | 27 | 12.2 | 7 | 11.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 49 | 59.0 | |||||||||||||

| Perceived impact on resident/fellow training | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not currently training residents/fellows | 31 | 34.1 | 0.813 | 45 | 31.0 | 0.838 | 28 | 42.4 | 0.267 | 11 | 35.5 | 0.839 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.680 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.951 | 7 | 33.3 | 0.588 | 15 | 8.1 | 0.677 | 70 | 31.4 | 0.476 | 22 | 35.5 | 0.089 | 6 | 50.0 | 0.167 | 170 | 63.4 | 0.791 | |

| Hurts training experience | 49 | 53.9 | 84 | 57.9 | 30 | 45.5 | 16 | 51.6 | 2 | 100.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 11 | 52.4 | 18 | 6.0 | 129 | 57.9 | 33 | 53.2 | 4 | 33.3 | 284 | 63.1 | |||||||||||||

| Improves training experience | 4 | 4.4 | 6 | 4.1 | 2 | 3.0 | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 9.5 | 2 | 10.0 | 6 | 2.7 | 6 | 9.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 60.0 | |||||||||||||

| No overall impact | 7 | 7.7 | 10 | 6.9 | 6 | 9.1 | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 10.0 | 18 | 8.1 | 1 | 1.6 | 2 | 16.7 | 27 | 56.3 | |||||||||||||

| Warning patients if the surgeon is COVID-19 positive | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Absolutely | 66 | 74.2 | 0.298 | 102 | 70.3 | 0.343 | 49 | 74.2 | 0.200 | 28 | 90.3 | 0.209 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.886 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.084 | 17 | 77.3 | 0.717 | 23 | 5.7 | 0.026* | 160 | 72.4 | 0.380 | 41 | 67.2 | 0.369 | 11 | 84.6 | 0.134 | 383 | 64.4 | 0.273 | |

| Likely | 8 | 9.0 | 21 | 14.5 | 6 | 9.1 | 3 | 9.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 6 | 8.0 | 27 | 12.2 | 10 | 16.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 69 | 65.1 | |||||||||||||

| Less likely | 6 | 6.7 | 7 | 4.8 | 7 | 10.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 20.0 | 14 | 6.3 | 3 | 4.9 | 2 | 15.4 | 24 | 55.8 | |||||||||||||

| Not at all | 9 | 10.1 | 15 | 10.3 | 4 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 9.1 | 3 | 8.8 | 20 | 9.1 | 7 | 11.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 31 | 53.5 | |||||||||||||

| Research activities impacted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No research engagement | 31 | 36.5 | 0.091 | 42 | 29.4 | 0.006* | 20 | 31.3 | 0.731 | 12 | 41.4 | 0.394 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.316 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.443 | 9 | 40.9 | 0.427 | 7 | 5.5 | 0.134 | 59 | 27.8 | 0.211 | 20 | 33.3 | 0.084 | 6 | 46.2 | 0.549 | 121 | 58.7 | 0.031* | |

| Complete stop | 13 | 15.3 | 19 | 13.3 | 12 | 18.8 | 4 | 13.8 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 9.1 | 10 | 11.5 | 35 | 16.5 | 8 | 13.3 | 2 | 15.4 | 77 | 63.1 | |||||||||||||

| Decrease in productivity | 20 | 23.5 | 57 | 39.9 | 19 | 29.7 | 6 | 20.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 31.8 | 15 | 9.0 | 69 | 32.6 | 23 | 38.3 | 3 | 23.1 | 152 | 61.5 | |||||||||||||

| No change | 15 | 17.7 | 21 | 14.7 | 7 | 10.9 | 3 | 10.3 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 4 | 5.8 | 34 | 16.0 | 8 | 13.3 | 1 | 7.7 | 65 | 60.2 | |||||||||||||

| Increase in productivity | 6 | 7.1 | 4 | 2.8 | 6 | 9.4 | 4 | 13.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 4.6 | 1 | 1.6 | 15 | 7.1 | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 7.7 | 63 | 78.8 | |||||||||||||

| Surgery Impact | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Advise against | 67 | 16.0 | 0.533 | 102 | 22.5 | 0.990 | 43 | 10.9 | 0.383 | 26.0 | 6.9 | 0.108 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.360 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.360 | 14 | 3.8 | 0.498 | 28 | 7.4 | 0.668 | 153 | 30.3 | 0.628 | 46 | 11.6 | 0.416 | 10 | 2.8 | 0.610 | 352 | 62.8 | 0.993 | |

| Proceed with standard precautions | 15 | 20.3 | 0.971 | 25 | 22.3 | 0.668 | 16 | 32.7 | 0.051 | 4 | 14.8 | 0.479 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.474 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.474 | 1 | 6.7 | 0.190 | 4 | 4.7 | 0.347 | 49 | 28.5 | 0.036* | 8 | 16.0 | 0.458 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.110 | 81 | 58.7 | 0.229 | |

| Absent during intubation/extubation | 37 | 43.5 | 0.465 | 46 | 36.2 | 0.020* | 19 | 32.8 | 0.030* | 13 | 44.8 | 0.753 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.177 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.177 | 4 | 23.5 | 0.049* | 13 | 5.6 | 0.348 | 76 | 38.8 | 0.033* | 22 | 39.3 | 0.226 | 3 | 27.3 | 0.177 | 221 | 68.6 | 0.014* | |

| Additional PPE during surgery | 47 | 51.7 | 0.508 | 71 | 49.0 | 0.171 | 33 | 50.0 | 0.407 | 16 | 51.6 | 0.681 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.878 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.116 | 13 | 59.1 | 0.733 | 24 | 8.0 | 0.353 | 113 | 50.7 | 0.239 | 31 | 50.8 | 0.497 | 7 | 53.9 | 0.911 | 277 | 64.7 | 0.212 | |

Calculation of p-values was performed using a combination of chi-square and Fisher exact tests.

Comparisons are made between respondents with comorbidities and healthy individuals. Clinicians with no comorbidities were compared to those with one or more comorbidity. All percentages are calculated based upon the total number of responses received for each question and comorbidity combination.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, personal protective equipment.

p < 0.05, statistical significance.

When prompted, obesity was not associated with variations in personal impact and future perceptions (p> 0.05), but a perceived impact at 1 year varied significantly based on diagnosis (Table 4). Spine surgeons with hypertension (p = 0.004), tobacco use (p = 0.003), any comorbidity (p = 0.002), 1 comorbidity (p = 0.006), or 2 comorbidities (p = 0.020) had a significant association with increasing nonoperative care prior to surgery at 1 year. Telecommunication was also significantly associated with tobacco use (p = 0.025), diabetes (p = 0.009), and 2 comorbidities (p = 0.047).

Table 4.

Medical comorbidities and future perceptions

| Variable | Obesity |

Hypertension |

Current tobacco use |

Respiratory illness |

Renal disease |

Cancer |

Cardiac disease |

Diabetes |

1 Comorbidity |

2 Comorbidities |

3+ Comorbidities |

No comorbidities |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | No. | % | p-value | ||

| Belief that future guidelines are needed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 81 | 97.6 | 0.525 | 130 | 94.9 | 0.595 | 57 | 90.5 | 0.336 | 25 | 89.3 | 0.187 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.948 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.948 | 21 | 95.5 | 0.932 | 35 | 7.3 | 0.008* | 195 | 93.8 | 0.309 | 55 | 96.5 | 0.418 | 12 | 92.3 | 0.825 | 448 | 63.1 | 0.313 | |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 4 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 37.5 | |||||||||||||

| Unsure | 2 | 2.4 | 5 | 3.7 | 5 | 7.9 | 2 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 4.3 | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 7.7 | 21 | 65.6 | |||||||||||||

| Perceived impact in 1 year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 13 | 13.4 | 0.643 | 24 | 22.2 | 0.948 | 11 | 11.6 | 0.953 | 6 | 6.7 | 0.623 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.511 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.511 | 5 | 5.6 | 0.553 | 7 | 7.7 | 0.859 | 40 | 32.3 | 0.647 | 4 | 4.6 | 0.040* | 5 | 5.6 | 0.057 | 84 | 63.2 | 0.963 | |

| Heighted awareness of hygiene | 50 | 79.4 | 0.828 | 73 | 78.5 | 0.941 | 31 | 75.6 | 0.711 | 14 | 70.0 | 0.394 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.455 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.455 | 12 | 70.6 | 0.464 | 23 | 7.4 | 0.883 | 105 | 73.9 | 0.313 | 37 | 90.2 | 0.069 | 7 | 63.6 | 0.255 | 286 | 65.8 | 0.717 | |

| Increase use of PPE | 47 | 61.0 | 0.060 | 67 | 55.8 | 0.214 | 30 | 58.8 | 0.204 | 12 | 48.0 | 0.892 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.153 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.153 | 12 | 60.0 | 0.354 | 18 | 8.0 | 0.455 | 98 | 56.0 | 0.143 | 35 | 66.0 | 0.022* | 5 | 41.7 | 0.597 | 206 | 59.9 | 0.045* | |

| Ask patients to reschedule if sick | 40 | 50.6 | 0.064 | 53 | 41.4 | 0.698 | 28 | 49.1 | 0.164 | 11 | 42.3 | 0.776 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.081 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.762 | 10 | 47.6 | 0.458 | 13 | 7.0 | 0.784 | 81 | 42.6 | 0.462 | 24 | 44.4 | 0.484 | 7 | 53.9 | 0.298 | 173 | 60.7 | 0.291 | |

| Increase nonoperative measures prior to surgery | 19 | 24.1 | 0.163 | 38 | 28.8 | 0.004* | 20 | 33.9 | 0.003* | 5 | 19.2 | 0.816 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.228 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.228 | 6 | 27.3 | 0.241 | 10 | 11.4 | 0.101 | 52 | 26.9 | 0.006* | 17 | 30.4 | 0.020* | 3 | 23.1 | 0.600 | 78 | 52.0 | 0.002* | |

| Increase digital options for communication | 39 | 47.0 | 0.404 | 46 | 33.6 | 0.074 | 24 | 38.1 | 0.547 | 13 | 46.4 | 0.650 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.098 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.821 | 5 | 22.7 | 0.072 | 18 | 8.3 | 0.436 | 91 | 43.8 | 0.683 | 19 | 33.3 | 0.205 | 5 | 38.5 | 0.795 | 199 | 63.4 | 0.850 | |

| How likely to attend a conference in 1 year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Likely | 54 | 65.1 | 0.232 | 90 | 66.2 | 0.626 | 39 | 61.9 | 0.490 | 19 | 67.9 | 0.997 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.627 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.678 | 13 | 59.1 | 0.004* | 21 | 6.1 | 0.325 | 132 | 63.8 | 0.384 | 34 | 59.7 | 0.341 | 9 | 69.2 | 0.478 | 321 | 64.7 | 0.295 | |

| Not likely | 3 | 3.6 | 8 | 5.9 | 7 | 11.1 | 2 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 27.3 | 3 | 7.9 | 14 | 6.8 | 4 | 7.0 | 2 | 15.4 | 35 | 63.6 | |||||||||||||

| Unsure | 26 | 31.3 | 38 | 27.9 | 17 | 27.0 | 7 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 13 | 10.2 | 61 | 29.5 | 19 | 33.3 | 2 | 15.4 | 115 | 58.4 | |||||||||||||

| Timeframe to resume elective surgery | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| < 2 Weeks | 5 | 5.5 | 0.720 | 5 | 3.5 | 0.279 | 4 | 6.1 | 0.399 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.396 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.850 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.843 | 3 | 13.6 | 0.058 | 1 | 6.3 | 0.902 | 14 | 6.3 | 0.175 | 2 | 3.3 | 0.359 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.923 | 15 | 48.4 | 0.178 | |

| 2–4 Weeks | 16 | 17.6 | 29 | 20.1 | 9 | 13.6 | 6 | 19.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 8 | 8.8 | 41 | 18.5 | 9 | 14.8 | 3 | 23.1 | 83 | 61.0 | |||||||||||||

| 1–2 Months | 15 | 16.5 | 24 | 16.7 | 8 | 12.1 | 4 | 12.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.6 | 5 | 5.5 | 29 | 13.1 | 10 | 16.4 | 2 | 15.4 | 86 | 67.7 | |||||||||||||

| > 2 Months | 3 | 3.3 | 4 | 2.8 | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 8.0 | 9 | 4.1 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 69.7 | |||||||||||||

| No current stoppage | 11 | 12.1 | 21 | 14.6 | 10 | 15.2 | 1 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 5 | 9.6 | 26 | 11.7 | 11 | 18.0 | 1 | 7.7 | 47 | 55.3 | |||||||||||||

| Unknown | 41 | 45.1 | 61 | 42.4 | 33 | 50.0 | 20 | 64.5 | 2 | 100.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 12 | 54.6 | 17 | 6.3 | 103 | 46.4 | 28 | 45.9 | 7 | 53.9 | 254 | 64.8 | |||||||||||||

| Anticipated # weeks to resume baseline activity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| < 2 Weeks | 10 | 11.8 | 0.450 | 13 | 9.3 | 0.041* | 10 | 15.6 | 0.805 | 1 | 3.5 | 0.403 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.307 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.160 | 3 | 13.6 | 0.216 | 3 | 4.4 | 0.082 | 24 | 11.5 | 0.126 | 6 | 10.0 | 0.267 | 1 | 7.7 | 0.876 | 65 | 67.7 | 0.039* | |

| 2–4 Weeks | 24 | 28.2 | 43 | 30.7 | 15 | 23.4 | 9 | 31.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 36.4 | 12 | 11.1 | 58 | 27.8 | 19 | 31.7 | 4 | 30.8 | 96 | 54.2 | |||||||||||||

| 4–6 Weeks | 19 | 22.4 | 34 | 24.3 | 15 | 23.4 | 6 | 20.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 5 | 22.7 | 13 | 10.6 | 49 | 23.4 | 15 | 25.0 | 3 | 23.1 | 110 | 62.2 | |||||||||||||

| 6–8 Weeks | 13 | 15.3 | 21 | 15.0 | 10 | 15.6 | 5 | 17.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 4.3 | 32 | 15.3 | 7 | 11.7 | 2 | 15.4 | 67 | 62.0 | |||||||||||||

| > 8 Weeks | 19 | 22.4 | 29 | 20.7 | 14 | 21.9 | 8 | 27.6 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 27.3 | 6 | 4.1 | 46 | 22.0 | 13 | 21.7 | 3 | 23.1 | 139 | 69.2 | |||||||||||||

| % Telecommunication clinical visits/wk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–25 | 51 | 55.4 | 0.355 | 77 | 53.1 | 0.147 | 42 | 63.6 | 0.025* | 18 | 58.1 | 0.326 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.845 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.168 | 9 | 40.9 | 0.599 | 20 | 7.7 | 0.009* | 112 | 50.2 | 0.323 | 36 | 59.0 | 0.047* | 9 | 69.2 | 0.389 | 241 | 60.6 | 0.068 | |

| 26–50 | 11 | 12.0 | 26 | 17.9 | 11 | 16.7 | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 18.2 | 11 | 14.1 | 38 | 17.0 | 12 | 19.7 | 1 | 7.7 | 67 | 56.8 | |||||||||||||

| 51–75 | 5 | 5.4 | 12 | 8.3 | 4 | 6.1 | 1 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 18.2 | 2 | 3.6 | 18 | 8.1 | 5 | 8.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 54 | 70.1 | |||||||||||||

| 76–100 | 25 | 27.2 | 30 | 20.7 | 9 | 13.6 | 10 | 32.3 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 5 | 22.7 | 4 | 2.7 | 55 | 24.7 | 8 | 13.1 | 3 | 23.1 | 142 | 68.3 | |||||||||||||

Calculation of p-values was performed using a combination of chi-square and Fisher exact tests.

Comparisons are made between respondents with comorbidities and healthy individuals. Clinicians with no comorbidities were compared to those with one or more comorbidity. All percentages are calculated based upon the total number of responses received for each question and comorbidity combination.

PPE, personal protective equipment.

p < 0.05, statistical significance.

Multivariate regression analysis controlling for baseline demographics, such as age, and practice-specific factors revealed that tobacco users were more likely to get prophylactically tested for COVID-19 (OR, 9.90; 95% CI, 1.10–89.14; p = 0.041). Those with hypertension were more likely to cite personal health as a current stressor (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.00–2.22; p = 0.046), whereas spine surgeons with tobacco use were less likely to cite family health as a stressor (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28–0.97; p =0.039. Similarly, respondents with current tobacco use were more likely to still be performing elective spine surgery during the pandemic (OR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.46–4.72; p = 0.001), more likely to pursue nonoperative care at 1 year (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.0–3.28; p = 0.39), and less likely to be absent during intubation/extubation (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.28–0.97; p = 0.038). In addition, those with hypertension were less likely to perceive their government’s pandemic management favorably (OR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.45–0.99; p = 0.047) and were less likely to warn their patients should they become infected with COVID-19 (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37–0.91; p = 0.017). In comparison, under similar circumstances, those with respiratory illnesses were far more likely to warn their patients of a COVID-19 infection (OR, 5.23; 95% CI, 1.20–22.83; p = 0.028). Clinicians reporting a current tobacco use history were less likely to report utilization of telecommunication for recent clinical visits (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.31–0.86; p = 0.011) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate assessment of medical comorbidities & COVID-19 survey responses

| Assessed survey responses | Age |

Female sex |

Orthopaedics |

Neurosurgery |

Trauma |

Academic Practice |

Private practice |

Public/local practice |

Obese |

Hypertension |

Current tobacco use |

Respiratory illness |

Cardiac disease |

Diabetes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Reasons for COVID-19 testing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personally tested for COVID-19 | 0.99 | 0.74–1.33 | 0.962 | 2.56 | 1.04–6.29 | 0.041* | 2.71 | 0.55–13.27 | 0.219 | 3.47 | 0.72–16.71 | 0.121 | 1.98 | 0.91–4.28 | 0.083 | 1.35 | 0.69–2.65 | 0.386 | 0.42 | 0.13–1.34 | 0.143 | 0.55 | 0.19–1.55 | 0.259 | 1.06 | 0.43–2.59 | 0.902 | 0.79 | 0.33–1.89 | 0.603 | 0.18 | 0.02–1.33 | 0.093 | 1.05 | 0.23–4.76 | 0.949 | 1.93 | 0.41–9.09 | 0.404 | 0.85 | 0.19–3.79 | 0.834 | |

| Direct contact with COVID-19 positive patient | 1.03 | 0.70–1.51 | 0.873 | 0.82 | 0.20–3.34 | 0.782 | 0.21 | 0.02–2.43 | 0.210 | 0.30 | 0.03–3.51 | 0.340 | 1.76 | 0.51–6.14 | 0.374 | 1.11 | 0.41–3.03 | 0.835 | 1.64 | 0.41–6.59 | 0.488 | 1.89 | 0.53–6.74 | 0.324 | 0.50 | 0.13–1.98 | 0.325 | 0.59 | 0.18–1.88 | 0.370 | 0.14 | 0.02–1.20 | 0.073 | 0.75 | 0.06–10.04 | 0.825 | 2.04 | 0.33–12.61 | 0.441 | 1.03 | 0.17–6.23 | 0.971 | |

| Prophylactic | 3.05 | 1.22–7.63 | 0.017* | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 108.44 | 0.85–13,777.31 | 0.058 | 126.17 | 0.92–17289.75 | 0.054 | 18.97 | 2.39–150.68 | 0.005* | 0.92 | 0.17–4.99 | 0.919 | 0.07 | 0.00–6.09 | 0.247 | 0.07 | 0.00–1.51 | 0.090 | 3.79 | 0.49–29.12 | 0.200 | 0.18 | 0.01–2.27 | 0.183 | 9.90 | 1.10–89.14 | 0.041* | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 0.54 | .01–42.62 | 0.780 | 1.26 | 0.09–18.54 | 0.866 | |

| Demonstrated symptoms | 0.82 | 0.56–1.18 | 0.280 | 1.46 | 0.40–5.28 | 0.564 | 2.00 | 0.23–17.69 | 0.532 | 1.38 | 0.16–12.01 | 0.770 | 0.32 | 0.08–1.17 | 0.085 | 0.82 | 0.32–2.08 | 0.670 | 0.93 | 0.24–3.59 | 0.918 | 0.72 | 0.21–2.45 | 0.604 | 1.21 | 0.33–4.37 | 0.772 | 1.42 | 0.48–4.22 | 0.526 | 1.73 | 0.44–6.86 | 0.433 | 3.46 | 0.25–46.99 | 0.352 | 0.47 | 0.07–3.03 | 0.428 | 0.35 | 0.06–2.14 | 0.258 | |

| Ask to be tested | 0.70 | 0.29–1.69 | 0.430 | 3.53 | 0.28–44.17 | 0.328 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 1.49 | 0.14–15.86 | 0.741 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 6.48 | 0.41–102.85 | 0.185 | 2.36 | 0.17–32.46 | 0.522 | 7.55 | 0.99–57.45 | 0.051 | 1.75 | 0.13–22.97 | 0.672 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 3.58 | 0.38–34.15 | 0.267 | |

| Current stressors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal health | 1.10 | 0.95–1.28 | 0.199 | 0.72 | 0.39–1.35 | 0.307 | 0.59 | 0.26–1.32 | 0.196 | 0.69 | 0.30–1.57 | 0.379 | 1.11 | 0.70–1.77 | 0.657 | 0.97 | 0.68–1.38 | 0.855 | 0.73 | 0.47–1.16 | 0.185 | 1.26 | 0.79–2.03 | 0.335 | 1.33 | 0.86–2.07 | 0.199 | 1.50 | 1.01–2.23 | 0.046* | 0.81 | 0.48–1.37 | 0.428 | 1.55 | 0.72–3.34 | 0.264 | 2.49 | 0.98–6.30 | 0.055 | 0.81 | 0.41–1.59 | 0.531 | |

| Family health | 1.16 | 0.94–1.43 | 0.168 | 0.29 | 0.15–0.56 | < 0.001* | 1.23 | 0.43–3.50 | 0.699 | 1.45 | 0.50–4.25 | 0.494 | 1.24 | 0.65–2.35 | 0.513 | 1.12 | 0.69–1.81 | 0.644 | 1.23 | 0.65–2.33 | 0.521 | 1.00 | 0.53–1.86 | 0.988 | 1.24 | 0.65–2.38 | 0.515 | 0.95 | 0.55–1.67 | 0.869 | 0.52 | 0.28–0.97 | 0.039* | 1.69 | 0.48–5.96 | 0.412 | 1.15 | 0.32–4.12 | 0.834 | 0.79 | 0.33–1.93 | 0.609 | |

| Community health | 0.96 | 0.83–1.12 | 0.627 | 1.14 | 0.63–2.06 | 0.675 | 2.31 | 1.00–5.34 | 0.050 | 2.12 | 0.91–4.97 | 0.082 | 1.77 | 1.11–2.81 | 0.017* | 0.71 | 0.50–1.01 | 0.058 | 0.91 | 0.58–1.42 | 0.665 | 0.67 | 0.42–1.08 | 0.102 | 0.65 | 0.42–1.03 | 0.066 | 0.89 | 0.60–1.33 | 0.578 | 1.41 | 0.84–2.37 | 0.189 | 0.48 | 0.20–1.11 | 0.087 | 1.94 | 0.81–4.67 | 0.139 | 1.89 | 0.97–3.71 | 0.063 | |

| Hospital capacity | 0.97 | 0.83–1.12 | 0.662 | 1.15 | 0.63–2.11 | 0.644 | 1.08 | 0.48–2.44 | 0.852 | 1.18 | 0.52–2.69 | 0.700 | 1.63 | 1.02–2.59 | 0.041* | 1.42 | 1.00–2.03 | 0.053 | 0.61 | 0.38–0.99 | 0.044* | 2.28 | 1.42–3.68 | 0.001* | 1.28 | 0.82–2.00 | 0.284 | 1.39 | 0.92–2.08 | 0.114 | 0.75 | 0.44–1.29 | 0.298 | 0.97 | 0.43–2.15 | 0.932 | 0.71 | 0.28–1.79 | 0.470 | 0.51 | 0.24–1.06 | 0.071 | |

| Timeline to resume clinical practice | 0.94 | 0.81–1.08 | 0.371 | 1.45 | 0.80–2.62 | 0.217 | 1.06 | 0.48–2.32 | 0.887 | 0.96 | 0.43–2.14 | 0.928 | 0.95 | 0.60–1.51 | 0.837 | 0.94 | 0.66–1.33 | 0.716 | 1.12 | 0.72–1.74 | 0.622 | 0.70 | 0.43–1.12 | 0.133 | 0.89 | 0.57–1.38 | 0.591 | 0.77 | 0.52–1.15 | 0.209 | 0.95 | 0.56–1.59 | 0.838 | 0.56 | 0.25–1.26 | 0.158 | 1.20 | 0.50–2.85 | 0.685 | 0.77 | 0.38–1.52 | 0.447 | |

| Government/leadership | 0.94 | 0.78–1.13 | 0.507 | 2.05 | 1.08–3.91 | 0.028* | 2.19 | 0.76–6.29 | 0.145 | 1.79 | 0.62–5.15 | 0.278 | 0.98 | 0.55–1.74 | 0.945 | 1.57 | 0.97–2.54 | 0.068 | 1.48 | 0.82–2.68 | 0.198 | 1.47 | 0.79–2.72 | 0.226 | 1.14 | 0.66–1.97 | 0.647 | 0.85 | 0.50–1.46 | 0.565 | 0.85 | 0.50–1.46 | 0.565 | 1.16 | 0.45–2.96 | 0.758 | 1.81 | 0.67–4.88 | 0.241 | 0.84 | 0.34–2.12 | 0.716 | |

| Return to nonessential activities | 1.01 | 0.82–1.25 | 0.923 | 1.33 | 0.61–2.89 | 0.470 | 1.35 | 0.46–3.99 | 0.586 | 1.13 | 0.38–3.39 | 0.829 | 1.77 | 0.99–3.17 | 0.052 | 1.66 | 0.96–2.86 | 0.067 | 1.70 | 0.88–3.29 | 0.117 | 1.29 | 0.63–2.64 | 0.493 | 0.75 | 0.38–1.48 | 0.407 | 1.32 | 0.76–2.30 | 0.324 | 1.32 | 0.76–2.30 | 0.324 | 1.04 | 0.35–3.09 | 0.945 | 0.89 | 0.25–3.18 | 0.858 | 0.66 | 0.22–1.94 | 0.448 | |

| Economic issues | 0.85 | 0.73–0.99 | 0.032* | 0.70 | 0.38–1.30 | 0.262 | 1.78 | 0.77 ,4.07 | 0.175 | 1.70 | 0.73–3.93 | 0.216 | 0.95 | 0.59–1.51 | 0.823 | 0.55 | 0.38–0.78 | 0.001* | 1.26 | 0.80–1.98 | 0.314 | 0.51 | 0.31–0.82 | 0.006* | 0.81 | 0.52–1.27 | 0.359 | 0.87 | 0.58–1.312 | 0.514 | 0.87 | 0.58–1.31 | 0.514 | 2.97 | 1.27–6.96 | 0.012* | 1.86 | 0.77–4.50 | 0.170 | 0.61 | 0.30–1.26 | 0.184 | |

| Clinical practice | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quarantine | 1.03 | 0.86–1.23 | 0.735 | 2.07 | 1.08–3.95 | 0.028* | 1.35 | 0.52–3.52 | 0.542 | 2.28 | 0.87–5.98 | 0.094 | 0.80 | 0.44–1.47 | 0.472 | 0.66 | 0.44–1.00 | 0.049* | 0.91 | 0.55–1.52 | 0.731 | 0.54 | 0.30–0.97 | 0.038* | 0.83 | 0.48–1.41 | 0.483 | 1.29 | 0.82–2.04 | 0.277 | 1.29 | 0.82–2.04 | 0.277 | 1.88 | 0.84–4.24 | 0.127 | 0.42 | 0.11–1.56 | 0.196 | 1.56 | 0.74–3.27 | 0.240 | |

| Still performing elective surgery | 1.13 | 0.93–1.37 | 0.218 | 0.44 | 0.15–1.27 | 0.128 | 1.23 | 0.40 ,3.83 | 0.718 | 0.78 | 0.25–2.45 | 0.665 | 0.32 | 0.14–0.72 | 0.006* | 2.18 | 1.33–3.55 | 0.002* | 0.82 | 0.40–1.66 | 0.575 | 1.56 | 0.80–3.04 | 0.191 | 1.17 | 0.65–2.09 | 0.604 | 1.24 | 0.76–2.02 | 0.396 | 1.24 | 0.76–2.02 | 0.396 | 0.16 | 0.02–1.22 | 0.077 | 0.92 | 0.29–2.91 | 0.887 | 1.26 | 0.57–2.77 | 0.569 | |

| Essential/emergency spine surgery | 0.91 | 0.73–1.14 | 0.407 | 0.52 | 0.24–1.14 | 0.103 | 1.44 | 0.45–4.63 | 0.536 | 2.22 | 0.66–7.44 | 0.196 | 0.77 | 0.40–1.49 | 0.446 | 2.35 | 1.33–4.15 | 0.003* | 0.79 | 0.43–1.45 | 0.446 | 0.82 | 0.43–1.57 | 0.556 | 0.61 | 0.33–1.12 | 0.113 | 0.88 | 0.48–1.59 | 0.663 | 0.88 | 0.48–1.59 | 0.663 | 0.69 | 0.25–1.93 | 0.477 | 0.97 | 0.30–3.18 | 0.962 | 1.90 | 0.55–6.58 | 0.310 | |

| Advise against | 1.01 | 0.85–1.19 | 0.940 | 0.79 | 0.42–1.51 | 0.475 | 0.74 | 0.29–1.87 | 0.524 | 0.52 | 0.21–1.33 | 0.174 | 1.57 | 0.90–2.74 | 0.113 | 0.82 | 0.55–1.21 | 0.323 | 1.73 | 0.99–3.03 | 0.054 | 0.64 | 0.39–1.08 | 0.094 | 1.15 | 0.69–1.92 | 0.598 | 0.89 | 0.58–1.38 | 0.605 | 0.89 | 0.58–1.38 | 0.605 | 1.90 | 0.70–5.12 | 0.205 | 0.60 | 0.24–1.53 | 0.288 | 1.20 | 0.56–2.58 | 0.642 | |

| Proceed with standard precautions | 1.11 | 0.91–1.35 | 0.265 | 0.26 | 0.08–0.87 | 0.067 | 1.15 | 0.41 ,3.26 | 0.583 | 1.46 | 0.51–4.18 | 0.287 | 1.66 | 0.94–2.93 | 0.244 | 0.95 | 0.60–1.51 | 0.936 | 0.65 | 0.34–1.27 | 0.114 | 1.40 | 0.77–2.53 | 0.234 | 0.92 | 0.50–1.69 | 0.795 | 1.07 | 0.64–1.81 | 0.604 | 1.07 | 0.64–1.81 | 0.604 | 0.85 | 0.29–2.55 | 0.543 | 0.19 | 0.03–1.49 | 0.133 | 0.53 | 0.18–1.56 | 0.176 | |

| Absent during intubation/extubation | 0.84 | 0.72–0.98 | 0.076 | 0.73 | 0.39–1.36 | 0.805 | 0.80 | 0.33–1.89 | 0.966 | 0.84 | 0.35–2.04 | 0.974 | 1.03 | 0.64–1.66 | 0.618 | 1.27 | 0.88–1.84 | 0.135 | 1.04 | 0.65–1.68 | 0.825 | 1.22 | 0.74–2.00 | 0.191 | 1.11 | 0.70–1.77 | 0.751 | 0.76 | 0.50–1.16 | 0.307 | 0.76 | 0.50–1.16 | 0.307 | 1.00 | 0.45–2.22 | 0.980 | 0.42 | 0.14–1.29 | 0.268 | 0.96 | 0.47–1.97 | 0.974 | |

| Additional PPE during surgery | 0.91 | 0.78–1.06 | 0.214 | 1.51 | 0.81–2.84 | 0.198 | 1.55 | 0.67–3.63 | 0.307 | 2.00 | 0.84–4.72 | 0.115 | 0.86 | 0.54–1.37 | 0.525 | 1.20 | 0.84–1.71 | 0.319 | 0.72 | 0.45–1.13 | 0.155 | 1.27 | 0.78–2.06 | 0.336 | 0.94 | 0.60–1.48 | 0.786 | 0.85 | 0.57–1.27 | 0.420 | 0.85 | 0.57–1.27 | 0.420 | 0.87 | 0.40–1.87 | 0.720 | 1.66 | 0.67–4.13 | 0.273 | 1.76 | 0.87–3.55 | 0.114 | |

| % Telecommunication clinical visits/wk | 0.94 | 0.81–1.08 | 0.380 | 1.69 | 0.95–3.01 | 0.077 | 0.68 | 0.32–1.46 | 0.328 | 0.85 | 0.40–1.84 | 0.689 | 0.99 | 0.64–1.54 | 0.972 | 1.78 | 1.27–2.49 | 0.001* | 1.08 | 0.70–1.67 | 0.732 | 0.71 | 0.44–1.14 | 0.153 | 0.97 | 0.63–1.49 | 0.874 | 0.88 | 0.61–1.27 | 0.489 | 0.88 | 0.61–1.27 | 0.489 | 0.89 | 0.42–1.91 | 0.768 | 1.67 | 0.76–3.66 | 0.200 | 0.67 | 0.36–1.26 | 0.218 | |

| Perceived impact in 1 year | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 1.08 | 0.88–1.33 | 0.449 | 0.69 | 0.29–1.64 | 0.403 | 0.98 | 0.33–2.89 | 0.974 | 1.15 | 0.38–3.42 | 0.806 | 0.98 | 0.51–1.86 | 0.943 | 1.53 | 0.90–2.60 | 0.117 | 1.41 | 0.73–2.73 | 0.309 | 2.67 | 1.42–5.03 | 0.002* | 0.84 | 0.44–1.60 | 0.591 | 0.93 | 0.54–1.61 | 0.808 | 0.93 | 0.54–1.61 | 0.808 | 1.57 | 0.60–4.07 | 0.358 | 1.24 | 0.43–3.58 | 0.695 | 1.13 | 0.47–2.71 | 0.789 | |

| Heighted awareness of hygiene | 0.89 | 0.76–1.04 | 0.292 | 1.23 | 0.65–2.33 | 0.427 | 1.58 | 0.68–3.69 | 0.790 | 1.59 | 0.67–3.76 | 0.984 | 1.05 | 0.64–1.72 | 0.964 | 0.77 | 0.52–1.12 | 0.149 | 0.65 | 0.40–1.06 | 0.207 | 0.43 | 0.26–0.72 | 0.001* | 1.20 | 0.74–1.96 | 0.604 | 0.81 | 0.53–1.23 | 0.676 | 0.81 | 0.53–1.23 | 0.676 | 0.76 | 0.34–1.71 | 0.273 | 1.14 | 0.47–2.78 | 0.713 | 1.30 | 0.64–2.64 | 0.946 | |

| Increase use of PPE | 0.92 | 0.79–1.08 | 0.318 | 0.98 | 0.53–1.83 | 0.950 | 0.84 | 0.36–1.93 | 0.678 | 1.23 | 0.53–2.87 | 0.625 | 1.06 | 0.65–1.72 | 0.828 | 0.68 | 0.47–0.99 | 0.042* | 0.49 | 0.30–0.79 | 0.004* | 0.61 | 0.37–1.00 | 0.051 | 1.51 | 0.94–2.44 | 0.089 | 1.14 | 0.75–1.74 | 0.527 | 1.14 | 0.75–1.74 | 0.835 | 0.86 | 0.38–1.97 | 0.727 | 1.58 | 0.65–3.85 | 0.315 | 1.05 | 0.52–2.10 | 0.893 | |

| Ask patients to reschedule if sick | 1.17 | 0.99–1.37 | 0.026* | 1.00 | 0.53–1.89 | 0.938 | 0.85 | 0.37–1.97 | 0.883 | 0.97 | 0.42–2.28 | 0.938 | 1.28 | 0.78–2.09 | 0.240 | 0.99 | 0.68–1.45 | 0.932 | 0.99 | 0.61–1.61 | 0.912 | 1.07 | 0.65–1.77 | 0.816 | 1.53 | 0.95–2.46 | 0.111 | 0.87 | 0.57–1.34 | 0.442 | 0.87 | 0.57–1.34 | 0.442 | 1.01 | 0.44–2.30 | 0.931 | 1.14 | 0.47–2.77 | 0.909 | 0.81 | 0.40–1.67 | 0.491 | |

| Increase nonoperative measures prior to surgery | 0.98 | 0.80–1.20 | 0.994 | 1.45 | 0.70–3.02 | 0.291 | 0.74 | 0.28–1.94 | 0.709 | 1.01 | 0.38–2.70 | 0.822 | 1.27 | 0.71–2.30 | 0.381 | 0.83 | 0.53–1.31 | 0.490 | 0.55 | 0.29–1.04 | 0.071 | 0.88 | 0.48–1.60 | 0.622 | 1.00 | 0.56–1.80 | 0.976 | 1.59 | 0.97–2.61 | 0.085 | 1.59 | 0.97–2.61 | 0.085 | 0.71 | 0.23–2.18 | 0.516 | 1.48 | 0.54–4.08 | 0.529 | 1.35 | 0.61–2.97 | 0.467 | |

| Increase digital options for communication | 1.14 | 0.97–1.34 | 0.112 | 1.34 | 0.72–2.49 | 0.352 | 1.07 | 0.46–2.52 | 0.871 | 1.36 | 0.57–3.22 | 0.491 | 1.14 | 0.70–1.87 | 0.591 | 1.08 | 0.74–1.57 | 0.685 | 0.67 | 0.41 ,1.09 | 0.107 | 0.80 | 0.49–1.33 | 0.393 | 1.39 | 0.86–2.25 | 0.180 | 0.58 | 0.38–0.90 | 0.015* | 0.58 | 0.38–0.90 | 0.015* | 0.97 | 0.42–2.25 | 0.949 | 0.42 | 0.15–1.20 | 0.105 | 1.57 | 0.78–3.16 | 0.210 | |

| Other perceptions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Media perceptions | 1.02 | 0.89–1.17 | 0.810 | 0.59 | 0.33–1.05 | 0.071 | 0.57 | 0.28–1.19 | 0.133 | 0.75 | 0.36–1.58 | 0.455 | 1.30 | 0.84–2.01 | 0.244 | 1.17 | 0.84–1.63 | 0.353 | 1.23 | 0.81–1.87 | 0.340 | 1.17 | 0.75–1.83 | 0.492 | 1.28 | 0.84–1.96 | 0.248 | 1.20 | 0.83–1.73 | 0.345 | 1.20 | 0.83–1.73 | 0.345 | 1.44 | 0.69–2.98 | 0.329 | 1.10 | 0.48–2.54 | 0.815 | 0.66 | 0.35–1.25 | 0.204 | |

| Perception of hospital effectiveness | 1.51 | 1.29–1.77 | < 0.001* | 0.61 | 0.34–1.10 | 0.103 | 1.47 | 0.62–3.46 | 0.381 | 1.17 | 0.49–2.80 | 0.724 | 1.28 | 0.78–2.09 | 0.335 | 1.98 | 1.38–2.85 | < 0.001* | 2.01 | 1.25–3.23 | 0.004* | 1.00 | 0.62–1.60 | 0.994 | 0.72 | 0.46–1.14 | 0.162 | 0.72 | 0.48–1.08 | 0.108 | 0.72 | 0.48–1.08 | 0.108 | 1.23 | 0.57–2.67 | 0.601 | 0.46 | 0.19–1.10 | 0.083 | 1.05 | 0.53–2.09 | 0.883 | |

| Perception of government effectiveness | 1.19 | 1.02–1.38 | 0.024* | 0.61 | 0.34–1.08 | 0.088 | 0.87 | 0.41 ,1.88 | 0.728 | 0.80 | 0.37–1.74 | 0.570 | 1.17 | 0.73–1.87 | 0.511 | 1.13 | 0.79–1.61 | 0.496 | 1.12 | 0.71–1.78 | 0.626 | 0.85 | 0.53–1.36 | 0.498 | 0.99 | 0.63–1.55 | 0.961 | 0.67 | 0.45–0.99 | 0.047* | 0.67 | 0.45–0.99 | 0.047* | 1.59 | 0.71–3.57 | 0.259 | 0.76 | 0.31–1.85 | 0.550 | 1.08 | 0.56–2.07 | 0.828 | |

| Warning patients if the surgeon is COVID-19 positive | 1.46 | 1.22–1.74 | < 0.001* | 0.82 | 0.43–1.59 | 0.564 | 1.34 | 0.52–3.44 | 0.548 | 1.76 | 0.67–4.65 | 0.255 | 1.10 | 0.65–1.87 | 0.709 | 0.57 | 0.37–0.88 | 0.010* | 0.87 | 0.49–1.54 | 0.633 | 0.55 | 0.32–0.96 | 0.037* | 0.88 | 0.52–1.49 | 0.629 | 0.58 | 0.37–0.91 | 0.017* | 0.58 | 0.37–0.91 | 0.017* | 5.23 | 1.20–22.83 | 0.028* | 0.96 | 0.33–2.79 | 0.940 | 0.50 | 0.25–0.99 | 0.048* | |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PPE, personal protective equipment.

All multivariate models were assessed using the same set of independent factors and included baseline demographics, practice-specific variables, and medical comorbidities. Renal disease and cancer were excluded from assessment due to low study prevalence.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess survey responses with simple binary outcomes where ordinal logistic regression was implemented for questions with ordinal scales.

p < 0.05, statistical significance.

When grouped by number of comorbidities in the multivariate regression model, spine surgeons with more comorbidities were more likely to cite personal health as a current stressor (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.07–1.63; p = 0.09) and more likely to be performing elective surgery (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.02–1.71; p = 0.030), though also perceived their hospital’s management unfavorably (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60–0.91; p = 0.005), were less likely to currently use telecommunication clinical visits (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.67–1.00; p = 0.05), and would less likely warn their patients of a personnel COVID-19 infection (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58–0.93; p = 0.010) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate assessment of number of medical comorbidities and COVID-19 survey responses

| Assessed survey responses | Age |

Female sex |

Orthopaedics |

Neurosurgery |

Trauma |

Academic Practice |

Private practice |

Public/local practice |

Number of comorbidities |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Reasons for COVID-19 testing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personally tested for COVID-19 | 1.02 | 0.76–1.35 | 0.917 | 2.47 | 1.01–6.00 | 0.047* | 2.51 | 0.56–11.29 | 0.230 | 3.06 | 0.69–13.50 | 0.140 | 1.95 | 0.91–4.18 | 0.087 | 1.32 | 0.68–2.59 | 0.413 | 0.45 | 0.14–1.40 | 0.168 | 0.58 | 0.21–1.62 | 0.298 | 0.80 | 0.51–1.28 | 0.357 | |

| Direct contact with COVID-19 positive patient | 1.05 | 0.72–1.51 | 0.804 | 0.78 | 0.20–3.02 | 0.723 | 0.31 | 0.03–3.37 | 0.339 | 0.39 | 0.04–4.13 | 0.432 | 1.64 | 0.50–5.31 | 0.412 | 1.11 | 0.42–2.94 | 0.830 | 1.86 | 0.48–7.22 | 0.368 | 1.85 | 0.54–6.29 | 0.328 | 0.70 | 0.38–1.28 | 0.244 | |

| Prophylactic | 2.04 | 1.01–4.13 | 0.048* | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 44.29 | 0.80–2446.18 | 0.064 | 57.56 | 1.10–3012.99 | 0.045* | 11.98 | 1.78–80.77 | 0.011* | 0.65 | 0.13–3.16 | 0.592 | 0.08 | 0.00–3.43 | 0.187 | 0.12 | 0.01–1.82 | 0.125 | 1.26 | 0.45–3.54 | 0.662 | |

| Demonstrated symptoms | 0.81 | 0.57–1.15 | 0.246 | 1.59 | 0.45–5.61 | 0.472 | 1.56 | 0.19–12.63 | 0.677 | 1.24 | 0.15–9.89 | 0.842 | 0.41 | 0.12–1.39 | 0.154 | 0.84 | 0.34–2.09 | 0.710 | 0.88 | 0.24–3.26 | 0.849 | 0.69 | 0.21–2.30 | 0.549 | 0.99 | 0.57–1.73 | 0.971 | |

| Ask to Be Tested | 0.98 | 0.47–2.05 | 0.954 | 2.82 | 0.25–32.26 | 0.405 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 2.11 | 0.22–20.13 | 0.516 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | - | 3.79 | 0.27–53.95 | 0.326 | 2.70 | 0.98–7.41 | 0.054 | |

| Current Stressors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal health | 1.12 | 0.97–1.29 | 0.123 | 0.73 | 0.39–1.35 | 0.313 | 0.60 | 0.27–1.34 | 0.211 | 0.70 | 0.31–1.57 | 0.387 | 1.11 | 0.70–1.77 | 0.647 | 0.95 | 0.67–1.36 | 0.795 | 0.77 | 0.49–1.21 | 0.259 | 1.27 | 0.79–2.03 | 0.320 | 1.32 | 1.07–1.63 | 0.009* | |

| Family health | 1.18 | 0.96–1.44 | 0.114 | 0.29 | 0.15–0.57 | < 0.001* | 1.35 | 0.47–3.90 | 0.579 | 1.56 | 0.52–4.64 | 0.425 | 1.29 | 0.68–2.44 | 0.440 | 1.09 | 0.68–1.77 | 0.711 | 1.28 | 0.68–2.41 | 0.444 | 0.99 | 0.53–1.84 | 0.970 | 0.89 | 0.68–1.18 | 0.421 | |

| Community health | 0.98 | 0.85–1.13 | 0.821 | 1.12 | 0.62–2.02 | 0.714 | 2.25 | 0.98–5.14 | 0.056 | 2.02 | 0.87–4.68 | 0.102 | 1.74 | 1.10–2.76 | 0.018* | 0.73 | 0.51–1.03 | 0.074 | 0.88 | 0.57–1.37 | 0.576 | 0.70 | 0.44–1.12 | 0.135 | 1.01 | 0.82–1.24 | 0.941 | |

| Hospital capacity | 0.98 | 0.84–1.13 | 0.747 | 1.15 | 0.63–2.09 | 0.650 | 1.07 | 0.48–2.40 | 0.868 | 1.18 | 0.52–2.67 | 0.693 | 1.60 | 1.01–2.54 | 0.045* | 1.39 | 0.97–1.98 | 0.071 | 0.62 | 0.38–1.00 | 0.049* | 2.19 | 1.37–3.51 | 0.001* | 1.02 | 0.82–1.26 | 0.880 | |

| Timeline to resume clinical practice | 0.94 | 0.81–1.08 | 0.358 | 1.44 | 0.80–2.60 | 0.227 | 1.04 | 0.47–2.29 | 0.917 | 0.95 | 0.43–2.11 | 0.898 | 0.96 | 0.61–1.52 | 0.876 | 0.94 | 0.66–1.33 | 0.721 | 1.11 | 0.72–1.72 | 0.640 | 0.71 | 0.44–1.14 | 0.160 | 0.83 | 0.68–1.03 | 0.087 | |

| Government/leadership | 0.93 | 0.78–1.12 | 0.456 | 2.04 | 1.07–3.89 | 0.029* | 2.22 | 0.76–6.46 | 0.144 | 1.83 | 0.63–5.33 | 0.268 | 1.00 | 0.56–1.78 | 0.990 | 1.57 | 0.97–2.54 | 0.066 | 1.52 | 0.84–2.75 | 0.165 | 1.53 | 0.82–2.82 | 0.178 | 1.02 | 0.78–1.33 | 0.894 | |

| Return to nonessential activities | 1.03 | 0.84–1.25 | 0.809 | 1.34 | 0.62–2.90 | 0.461 | 1.32 | 0.44–3.89 | 0.620 | 1.12 | 0.37–3.36 | 0.846 | 1.75 | 0.98–3.12 | 0.057 | 1.65 | 0.96–2.84 | 0.069 | 1.67 | 0.87–3.23 | 0.125 | 1.26 | 0.61–2.57 | 0.532 | 1.02 | 0.76–1.38 | 0.884 | |

| Economic issues | 0.85 | 0.74–0.98 | 0.029* | 0.72 | 0.39–1.33 | 0.296 | 1.77 | 0.78–4.03 | 0.170 | 1.71 | 0.75–3.92 | 0.206 | 0.97 | 0.61–1.54 | 0.890 | 0.55 | 0.39–0.78 | 0.001* | 1.31 | 0.84–2.05 | 0.229 | 0.53 | 0.33–0.84 | 0.008* | 0.92 | 0.75–1.14 | 0.457 | |

| Clinical Practice | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quarantine | 1.02 | 0.86–1.21 | 0.786 | 2.10 | 1.10–4.01 | 0.025* | 1.34 | 0.52–3.44 | 0.541 | 2.29 | 0.89–5.91 | 0.086 | 0.78 | 0.43–1.43 | 0.429 | 0.67 | 0.45–1.01 | 0.056 | 0.89 | 0.54–1.47 | 0.645 | 0.52 | 0.29–0.93 | 0.028* | 1.19 | 0.94–1.51 | 0.143 | |

| Still performing elective surgery | 1.10 | 0.91–1.32 | 0.324 | 0.44 | 0.15–1.28 | 0.131 | 1.13 | 0.35–3.64 | 0.836 | 0.74 | 0.23–2.42 | 0.620 | 0.33 | 0.14–0.74 | 0.007* | 2.21 | 1.36–3.59 | 0.001* | 0.77 | 0.38–1.55 | 0.466 | 1.61 | 0.83–3.12 | 0.156 | 1.32 | 1.02–1.71 | 0.032* | |

| Essential/emergency spine surgery | 0.92 | 0.74–1.14 | 0.453 | 0.51 | 0.24–1.12 | 0.096 | 1.41 | 0.45–4.35 | 0.555 | 2.15 | 0.66–7.00 | 0.202 | 0.75 | 0.39–1.44 | 0.392 | 2.37 | 1.35–4.18 | 0.003* | 0.76 | 0.42–1.38 | 0.364 | 0.82 | 0.44–1.54 | 0.539 | 0.91 | 0.68–1.24 | 0.558 | |

| Advise against | 0.99 | 0.84–1.16 | 0.856 | 0.80 | 0.42–1.52 | 0.498 | 0.77 | 0.30–1.97 | 0.584 | 0.54 | 0.21–1.40 | 0.208 | 1.57 | 0.90–2.73 | 0.113 | 0.82 | 0.56–1.22 | 0.329 | 1.74 | 1.00–3.03 | 0.051 | 0.64 | 0.38–1.06 | 0.082 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.25 | 0.966 | |

| Proceed with standard precautions | 1.07 | 0.89–1.30 | 0.393 | 0.26 | 0.08–0.88 | 0.065 | 1.10 | 0.39–3.10 | 0.691 | 1.47 | 0.52–4.21 | 0.308 | 1.63 | 0.93–2.87 | 0.247 | 0.95 | 0.60–1.51- | 0.946 | 0.63 | 0.32–1.21 | 0.090 | 1.37 | 0.76–2.47 | 0.242 | 0.96 | 0.73–1.27 | 0.879 | |

| Absent during intubation/extubation | 0.83 | 0.72–0.97 | 0.059 | 0.72 | 0.39–1.34 | 0.767 | 0.84 | 0.36–1.96 | 0.961 | 0.89 | 0.38–2.10 | 0.927 | 1.03 | 0.64–1.65 | 0.611 | 1.27 | 0.88–1.83 | 0.139 | 1.06 | 0.66–1.70 | 0.850 | 1.20 | 0.73–1.95 | 0.222 | 0.78 | 0.62–0.97 | 0.060 | |

| Additional PPE during surgery | 0.93 | 0.80–1.07 | 0.298 | 1.49 | 0.79–2.79 | 0.217 | 1.61 | 0.69–3.75 | 0.269 | 2.00 | 0.85–4.72 | 0.114 | 0.86 | 0.54–1.38 | 0.533 | 1.20 | 0.84 ,1.71 | 0.315 | 0.72 | 0.46–1.14 | 0.164 | 1.29 | 0.79–2.08 | 0.307 | 0.95 | 0.77–1.17 | 0.637 | |

| % Telecommunication clinical visits/wk | 0.96 | 0.84–1.10 | 0.556 | 1.66 | 0.93–2.96 | 0.085 | 0.68 | 0.32–1.46 | 0.325 | 0.83 | 0.39–1.79 | 0.639 | 0.99 | 0.64–1.54 | 0.961 | 1.74 | 1.25–2.43 | 0.001* | 1.11 | 0.72–1.71 | 0.651 | 0.72 | 0.45–1.15 | 0.168 | 0.82 | 0.67–1.00 | 0.050* | |

| Perceived impact in 1 year | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No change | 1.09 | 0.90–1.33 | 0.375 | 0.70 | 0.30–1.65 | 0.417 | 1.00 | 0.35–2.92 | 0.994 | 1.16 | 0.39–3.42 | 0.792 | 0.97 | 0.51–1.84 | 0.936 | 1.53 | 0.90–2.59 | 0.118 | 1.44 | 0.75–2.78 | 0.278 | 2.67 | 1.43–5.00 | 0.002* | 0.96 | 0.72–1.27 | 0.771 | |

| Heighted awareness of hygiene | 0.88 | 0.76–1.03 | 0.264 | 1.22 | 0.64–2.30 | 0.467 | 1.66 | 0.71–3.86 | 0.831 | 1.63 | 0.69–3.85 | 0.938 | 1.06 | 0.65–1.75 | 0.924 | 0.76 | 0.52–1.12 | 0.149 | 0.65 | 0.40–1.05 | 0.174 | 0.44 | 0.27–0.72 | 0.001* | 0.96 | 0.77–1.19 | 0.712 | |

| Increase use of PPE | 0.92 | 0.79–1.07 | 0.486 | 0.97 | 0.52–1.81 | 0.880 | 0.85 | 0.37–1.95 | 0.697 | 1.24 | 0.53–2.88 | 0.670 | 1.07 | 0.66–1.75 | 0.694 | 0.68 | 0.47–0.98 | 0.099 | 0.50 | 0.31–0.80 | 0.011* | 0.62 | 0.38–1.01 | 0.110 | 1.22 | 0.98–1.52 | 0.083 | |

| Ask patients to reschedule if sick | 1.13 | 0.97–1.32 | 0.066 | 0.99 | 0.52–1.87 | 0.950 | 0.84 | 0.37–1.94 | 0.816 | 0.99 | 0.42–2.30 | 0.950 | 1.32 | 0.81–2.15 | 0.198 | 0.99 | 0.67–1.44 | 0.929 | 1.00 | 0.62–1.62 | 0.923 | 1.10 | 0.67–1.81 | 0.724 | 1.08 | 0.87–1.34 | 0.624 | |

| Increase nonoperative measures prior to surgery | 1.00 | 0.83–1.21 | 0.879 | 1.43 | 0.69–2.98 | 0.306 | 0.68 | 0.26–1.80 | 0.562 | 0.94 | 0.35–2.52 | 0.964 | 1.24 | 0.69–2.23 | 0.451 | 0.85 | 0.54–1.33 | 0.533 | 0.55 | 0.30–1.04 | 0.072 | 0.88 | 0.48–1.59 | 0.643 | 1.38 | 1.07–1.78 | 0.017 | |

| Increase digital options for communication | 1.08 | 0.93–1.26 | 0.329 | 1.34 | 0.72–2.48 | 0.359 | 1.15 | 0.49–2.65 | 0.751 | 1.45 | 0.62–3.39 | 0.397 | 1.16 | 0.71–1.89 | 0.547 | 1.08 | 0.75–1.56 | 0.687 | 0.65 | 0.40–1.06 | 0.082 | 0.81 | 0.49–1.33 | 0.398 | 0.88 | 0.71–1.10 | 0.275 | |

| Other Perceptions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Media perceptions | 1.01 | 0.88–1.16 | 0.868 | 0.60 | 0.34–1.06 | 0.078 | 0.58 | 0.28–1.20 | 0.142 | 0.76 | 0.36–1.60 | 0.470 | 1.30 | 0.84–2.01 | 0.242 | 1.16 | 0.84–1.62 | 0.369 | 1.27 | 0.83–1.93 | 0.273 | 1.17 | 0.75–1.82 | 0.497 | 1.12 | 0.92–1.37 | 0.247 | |

| Perception of hospital effectiveness | 1.49 | 1.28–1.74 | < 0.001* | 0.62 | 0.34–1.12 | 0.115 | 1.60 | 0.68–3.77 | 0.283 | 1.27 | 0.53–3.04 | 0.592 | 1.26 | 0.77–2.06 | 0.362 | 1.99 | 1.39–2.85 | < 0.001* | 1.95 | 1.22–3.11 | 0.005* | 0.98 | 0.61–1.57 | 0.939 | 0.74 | 0.60–0.91 | 0.005* | |

| Perception of government effectiveness | 1.14 | 0.99–1.32 | 0.073 | 0.62 | 0.35–1.10 | 0.105 | 0.89 | 0.42–1.92 | 0.770 | 0.84 | 0.39–1.82 | 0.653 | 1.19 | 0.75–1.90 | 0.467 | 1.15 | 0.81–1.63 | 0.449 | 1.13 | 0.71–1.78 | 0.608 | 0.87 | 0.55–1.39 | 0.572 | 0.93 | 0.76–1.14 | 0.483 | |

| Warning patients if the surgeon is COVID-19 positive | 1.40 | 1.18–1.67 | < 0.001* | 0.87 | 0.45–1.67 | 0.676 | 1.33 | 0.52–3.40 | 0.549 | 1.83 | 0.70–4.79 | 0.220 | 1.20 | 0.71–2.01 | 0.503 | 0.57 | 0.38–0.88 | 0.010* | 0.93 | 0.52–1.64 | 0.792 | 0.57 | 0.33–0.99 | 0.047* | 0.74 | 0.58–0.93 | 0.010* | |

All multivariate models were assessed using the same set of independent factors and included baseline demographics, practice, specific variables, and number of medical comorbidities.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess survey responses with simple binary outcomes where ordinal logistic regression was implemented for questions with ordinal scales.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PPE, personal protective equipment.

p < 0.05, statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 and its implications have raised concerns of patient health and safety. However, spine surgeons find themselves not only on the front-line during the height of such a pandemic but also facing the aftermath. Spine surgeons carry an increased work burden and are faced with stressors that compound health-related complications of comorbidities they may have. However, very little research has been published regarding spine surgeon well-being. Therefore, the authors utilized unique data from a COVID-19 global outreach survey to better understand health disparities in spine surgeons, which demonstrated that nearly 37% of participants had a major comorbidity, and those with more comorbidities were more likely to be concerned about their personal health, though they would also still be performing elective surgery. This is the first study to highlight the health of spine surgeons and how it relates to the perception of COVID-19 and how such a pandemic affects spine practices across the globe.

In a national health survey between 1986 and 1994, physicians were among the occupations with the lowest morbidity rate [11]. Similarly, fewer resources are allocated towards promoting preventative health measures for physicians when compared to other occupations. The current study identified a cohort of spine surgeons, most of whom were male and 44 years-of-age or younger, and yet nearly 37% reported a major comorbidity. While the United States has a nearly 10% incidence of diabetes, rates of obesity vary geographically [12,13], findings which were also highlighted in our present study as comorbidities varied across regions.

Hypertension and obesity were identified as the most commonly reported comorbidities, which is similar to recent studies analyzing COVID-19 [3]. Guan et al. [7] evaluated 1,590 patients diagnosed with COVID-19, noting an increased risk of ICU admission, invasive ventilation, or death in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (hazard ratio [HR], 2.681), hypertension (HR, 1.58), diabetes (HR, 1.59), or malignancy (HR, 3.50). Similarly, a meta-analysis of 6 studies evaluating patients with COVID-19 identified hypertension (OR, 2.29), respiratory disease (OR, 5.97), cardiac disease (OR, 2.93), diabetes (OR, 2.47) as significant risk factors associated with COVID-19 [14]. Tobacco use which has historically been linked to respiratory disease such as COPD also increases the risk of complications associated with COVID-19 [15]. In a meta-analysis of 15 studies, Alqahtani et al. [16] evaluated the mortality rates in COPD and tobacco use associated with COVID-19. Their analysis revealed that tobacco users were nearly 1.5 times more likely to have severe complications from COVID-19 when compared to nonsmokers, and tobacco users had a significantly higher mortality rate approaching 40%. Furthermore, tobacco users were more likely to perform surgery during the pandemic, exposing themselves to a deadly virus, and yet were also more likely to cite personal health as a stressor, highlighting the importance of smoking cessation. Given these findings, However, those with a respiratory illness were far more likely to inform their patients if they were diagnosed with COVID-19, suggesting a sense of sympathy.

In the present study, irrespective of the COVID-19 outbreak, spine surgeons with more comorbidities were more likely to cite personal health as a current stressor. A study by Gross et al. [17] demonstrated that of 915 physicians, only 65% had a regular source of medical care, and not having such care was associated with having a diagnosis of malignancy and not having the influenza vaccine at 6-year follow-up. Taub et al. [18] performed a study regarding guidelines for physician health and wellness. Though seemingly rhetorical, the value of healthy living habits and having a personal physician is undervalued, as the current study highlighted how spine surgeons also have modifiable comorbidities such as tobacco use and obesity. Furthermore, orthopedic surgical training can induce hypertension, though transient in nature [19]. Similarly, neurosurgery has been demonstrated to increase intraoperative blood pressure to levels higher than vigorous exercise [20]. Regardless, respondents with 1 comorbidity varied in their opinions regarding standard precautions and a lack of association between number of comorbidities and use of additional PPE during surgery infers riskier behavior by surgeons who would otherwise benefit from heightened awareness of their health.

Future perceptions and financial impacts from COVID-19 were also linked to spine surgeon health. While there was an association between comorbidity diagnosis and being present during intubation/extubation, multivariate analysis suggested that tobacco users were less likely to be absent during patient intubation/extubation. As restrictions are lifted allowing elective spine surgery to be performed, spine surgeons should continue to remain wary of their health. At baseline, surgeons practice meticulous sterile technique, but these techniques may expand into the clinical setting. Furthermore, use of masks and gloves for routine visits may become commonplace. This may even become expected, as spine surgeons with increasing comorbidities are at increased risk for complications from communicable diseases such as COVID-19. Telecommunication as a means of delivering healthcare is becoming more commonplace [21], though was less likely to be utilized in the present study by spine surgeons with current tobacco use.

Similarly, univariate analysis of comorbidities suggested that unhealthier spine surgeons with comorbidities such as hypertension and tobacco use perceived that they would increase nonoperative measures over the next year. Fortunately, duration of symptoms is an inconsistent marker of postoperative outcomes [22]. On the contrary, spine surgeons with more comorbidities were more likely to be performing elective surgery during the pandemic, though they also perceived their hospital administration negatively.

Like the current study, substance abuse (tobacco in the current study) contributes significantly to overall health status, especially as physicians have been noted to neglect their own health [23]. Interestingly, the unhealthier population using tobacco were more concerned with their personal health, though they were also more likely to still be performing elective surgery during the pandemic. This highlights the lack of introspection of surgeons who may be facing economic pressures and may forget about their health. Furthermore, work-hour restrictions and avoidance of sleep deprivation in medical professionals, from the standpoint of spine surgeon health as well as patient safety, has increased awareness of overall physician health [24,25]. Aside from the noted comorbidities, stress management, family support, and recreation have been cited as tools to battle fatigue or burnout [26,27]. Not only does such burn out affect individual surgeon health but may affect productivity, outcomes, and patient care.

However, the present study is not without limitations. For one, if a respondent did not note any comorbidities, this could also imply that they did not feel comfortable to disclose such information, raising issues of transparency and willingness to share personal information via such a survey. However, the distribution of comorbidities, noting hypertension and obesity as the most common, would imply that the trend of capturing such information may be representative given the fact that such conditions are well known to be more common. Also, the present study did not compare perceptions between outbreak and non-outbreak nations facing COVID-19 despite the vast prevalence of the virus. Furthermore, there were several instances where having “1 comorbidity” would significantly influence perceptions and impacts from COVID-19, though each individual diagnosis was insignificant, highlighting the likely low statistical power of individual diagnoses. It is expected that statistical significance would emerge with a higher number of respondents with each diagnosis in such scenarios.

CONCLUSION

The present study is the first to map out comorbidities of spine surgeons across the globe, highlighting comorbidities that had a significant impact on healthcare delivery and clinical decision-making related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Without question, COVID-19 has impacted patients and healthcare providers worldwide. This study has emphasized the importance of spine surgeon health. Spine surgeons are not immune to common comorbidities, and as the surgical landscape slowly returns to normalcy, it becomes even more relevant for this community to remain introspective about their health to prevent any individual health-related complications and maximize optimal patient care and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to Kaija Kurki-Suonio and Fernando Kijel from AO Spine (Davos, Switzerland)for their assistance with circulating the survey to AO Spine members.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mauffrey C, Trompeter A. Lead the way or leave the way: leading a Department of Orthopedics through the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2020;30:555–7. doi: 10.1007/s00590-020-02670-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lancaster EM, Sosa JA, Sammann A, et al. Rapid response of an academic surgical Department to the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for patients, surgeons, and the community. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:1064–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louie PK, Harada GK, McCarthy MH, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Spine Surgeons Worldwide. Global Spine J. 2020:219256822092578. doi: 10.1177/2192568220925783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568–76. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soh TLT, Ho SWL, Yap WMQ, et al. Spine surgery and COVID-19. Challenges and strategies from the front lines. J Bone Joint Sur. 2020 Apr 15; doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spagnolo P, Balestro E, Aliberti S, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis secondary to COVID-19: a call to arms? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;S2213-2600(20):30222–8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30222-8. . [Epub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000547. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green A, Duthie HL, Young HL, et al. Stress in surgeons. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1154–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255:625–33. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b2fa0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon burnout: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:1230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DJ, Fleming LE, Gómez-Marín O, et al. Morbidity ranking of U.S. workers employed in 206 occupations: the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 1986-1994. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:117–34. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000199520.23232.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhupathiraju SN, Hu FB. Epidemiology of obesity and diabetes and their cardiovascular complications. Circ Res. 2016;118:1723–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blundell JE, Baker JL, Boyland E, et al. Variations in the prevalence of obesity among European countries, and a consideration of possible causes. Obes Facts. 2017;10:25–37. doi: 10.1159/000455952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang B, Li R, Lu Z, et al. Does comorbidity increase the risk of patients with COVID-19: evidence from meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:6049–57. doi: 10.18632/aging.103000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laniado-Laborín R. Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Parallel epidemics of the 21 century. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:209–24. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alqahtani JS, Oyelade T, Aldhahir AM, et al. Prevalence, severity and mortality associated with COPD and Smoking in patients with COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]