Abstract

Fabricating a desired porous structure on the surface of biomedical polyetheretherketone (PEEK) implants for enhancing biological functions is crucial and difficult due to its inherent chemical inertness. In this study, a porous surface of PEEK implants was fabricated by controllable sulfonation using gaseous sulfur trioxide (SO3) for different time (5, 15, 30, 60 and 90 min). Micro-topological structure was generated on the surface of sulfonated PEEK implants preserving original mechanical properties. The protein absorption capacity and apatite forming ability was thus improved by the morphological and elemental change with higher degree of sulfonation. In combination of the appropriate micromorphology and bioactive sulfonate components, the cell adhesion, migration, proliferation and extracellular matrix secretion were obviously enhanced by the SPEEK-15 samples which were sulfonated for 15 min. Finding from this study revealed that controllable sulfonation by gaseous SO3 would be an extraordinarily strategy for improving osseointegration of PEEK implants by adjusting the microstructure and chemical composition while maintaining excellent mechanical properties.

Keywords: Polyetheretherketone, Sulfonation, Micro-topology, Mechanical strength, Osteointegration

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Micro-topological structure and bioactive sulfonate components was generated on the surface of PEEK implants.

-

•

The hydrophilicity and protein absorption capacity was significantly improved by appropriate degree of sulfonation.

-

•

Improved osseointegration could be achieved by this novel modification strategy.

1. Introduction

Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) has been widely used as medical implants including skull plates, intervertebral fusions and arthroscopic suture anchors benefiting from its excellent mechanical strength, chemical resistance and X-radiolucency [1,2]. Similar to PEEK materials, traditional metallic implants made of titanium alloys exhibit excellent corrosion resistance and high mechanical strength [3]. However, compared with titanium alloys, the elastic modulus of PEEK close to natural bone tissues will be able to avoid stress shielding which is often observed in titanium-based implants [4]. Moreover, the X-radiolucency of PEEK materials is meaningful in clinical applications as new bone formation around the implants can be easily observed after surgery and the nonunion of fracture or implant loosening can be detected as early as possible [[5], [6], [7]]. Unfortunately, in spite of the above attractive properties, the biological inertness of PEEK materials would impede in vivo osteointegration after implantation [[8], [9], [10]].

Recently, multiple PEEK modification studies have been conducted to improve the osseointegration between implants and bone tissue [[10], [11], [12]]. Three main strategies has been studied to overcome the bio-inert character of PEEK, including surface modification with either physical or chemical methods, preparation of functional PEEK composites by blending bioactive materials and designing three dimensional porous PEEK materials [13,14]. It is well known that porous microstructure is essential for the interaction between cells and implants as it could fulfill migration and proliferation of various cell types, enhance vascularization and bone tissue ingrowth, and eventually enhance osseointegration ability [15]. Cai et al. [16] incorporated meso-porous diopside (MD) into PEEK matrix to fabricate three dimensional porous PEEK/MD implant via cold press sintering and salt leaching method and the obtained porous PEEK/MD implants exhibited excellent osseointegration in vitro and in vivo. However, fully three dimensionally porous PEEK implants also suffered from reduction in mechanical strength due to high porosity and the relatively weak local bonds created during powder sintering or 3D printing [17,18]. Moreover, tissue necrosis may also occur at the center of fully three dimensionally porous implants owing to limited vascularization and nutrient supply [19].

It is widely accepted that biomaterial surface properties play a crucial role for the cell/implant interactions and will eventually influence integration between implant and bone tissue during healing process [20,21]. In this respect, some PEEK modification studies attempted to enhance bioactivity of PEEK implants via fabricating a surface porous structure and the results showed the biocompatibility and osseointegration was significant improved [10,22,23]. Consequently, creating surface porous microstructure is an effective way to increase the bioactivity of PEEK while preserving most of its advantageous properties [24]. In our previous work, a surface porous structure of PEEK implants was fabricated by sulfonation with concentrated sulfuric acid and the biological activity and osteointegration was significant enhanced while its mechanical properties was also damaged obviously [25].

The mechanical property of bone implants is a key factor for inevitable consideration in ultimate medical applications and excellent mechanical performance of PEEK materials makes it suitable for clinical treatments, especially in orthopedics [26]. The decrease of mechanical strength may lead to instability of the fracture site and new bone tissue cannot be formed at the initial stage of fracture healing and nonunion or malunion might be occurred [27]. Furthermore, PEEK implants will consistently subjected physiological stress after implantation. However, the inherent chemical and physical inertness of PEEK materials makes it difficult to fabricate a porous structure while maintaining excellent mechanical properties.

In this study, a novel fabricating strategy of bioactive PEEK materials was developed by controllable sulfonation for enhancing osseointegration and the compressive mechanical strength was well preserved to bear physiological stress. Benefiting from sulfonation with gaseous sulfur trioxide (SO3), a surface porous structure was produced on the surface of PEEK materials. Then the morphology of porous structure, chemical characteristics, wettability, protein adsorption capacity, mineralization behavior and mechanical property of the different sulfonated PEEK samples were systematically evaluated. Furthermore, in order to evaluate osseointegration properties of the modified PEEK, a series of in vitro experiments were performed including cell adhesion, spreading, proliferation as well as extracellular matrix secretion.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Biomedical grade PEEK was used in this study (Victrex, England). Phosphoric anhydride (P2O5) and concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%) were purchased from Beijing Chemical Works (China). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit were obtained from Thermo Scientific (USA). 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA).

2.2. Preparation of surface porous PEEK films

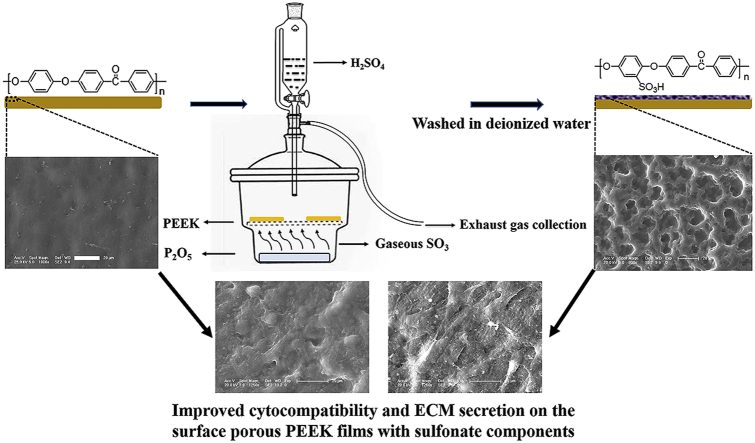

The fabrication process of surface porous PEEK implants was schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. Briefly, PEEK film was sulfonated by gaseous sulfur trioxide in a tailor glassware (as shown in Fig. 1) which was refitted from the glass vacuum desiccator. Two pieces of pure PEEK films (size: 40 × 40 × 0.2 mm3) were placed on the glassware bracket and 75 mg P2O5 was added in the bottom of refitted glassware. Then, 6 mL H2SO4 was titrated into refitted glassware via constant voltage funnel to generate gaseous sulfur trioxide (SO3) as the reaction between P2O5 and H2SO4. The whole process were preserved at 75 °C in thermostatic water bath to maintain gaseous state of SO3.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of fabricating surface porous PEEK implants by gaseous SO3 induced controllable sulfonation.

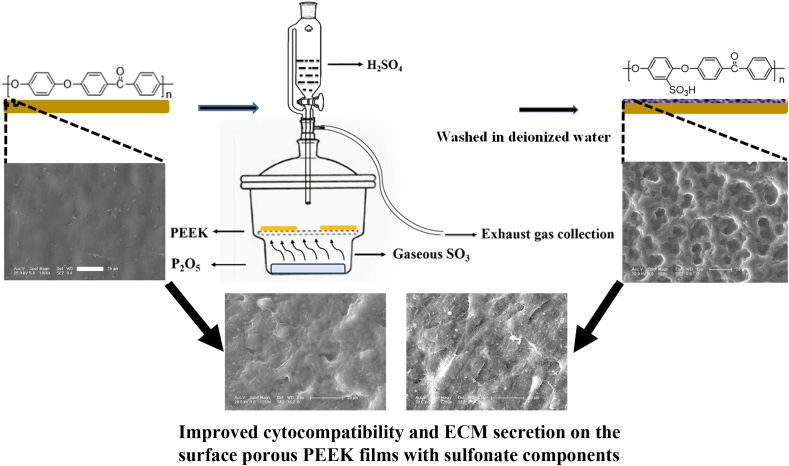

PEEK samples were treated by gaseous SO3 with five different durations: 5, 15, 30, 60 and 90 min, respectively. Finally, the samples were washed with deionized water at room temperature for 5 min, and the samples were left overnight to dry at room temperature. According to the different treating time, the samples are hereafter named as “SPEEK-5”, “SPEEK-15”, “SPEEK-30”, “SPEEK-60” and “SPEEK-90”. The reaction could be expressed by the following equation and graphic:

| 3H2SO4 + P2O5 = 3SO3 + 2H3PO4 |

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Surface morphology and chemical characterization

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Bio-Rad Win-IR Spectrometer, Watford, UK) spectra were recorded using the KBr slice method. An environmental scanning electron microscope (SEM, XL30 FEG, Philips) was used to observe the microstructure of PEEK films. Energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX) (XL-30W/TMP, Philips, Japan) was employed to analyze the elemental composition. For each sample, the size of 200 pores from five different SEM images were measured using Image J software to calculate micro-pore size distribution. N2 adsorption desorption measurements were carried out at 77K to characterize meso-pore properties. The specific surface areas of the samples were calculated by the BET (Brumauer - Emmett - Teller) method with N2 adsorption data.

2.3.2. Water contact angle analysis

Water contact angle measurements (VCA 2000, AST) were carried out to evaluate the surface hydrophilicity of the samples. At room temperature, 2 μL deionized water droplet was dropped onto the sample surface and pictures were taken by a camera after stabilization. Five samples of each group were tested to obtain the average data.

2.3.3. Protein adsorption

The assessment of protein adsorption capacity onto the samples was performed according to a previous protocol [28]. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was selected as a model protein. Disk specimens were immersed in BSA solution (pH = 7.35, 0.5 mg/mL, 0.5 mL in each well) under oscillation at a constant rate of 100 rpm, 37 °C for 5–180 min. The adsorbed protein was determined through the decrease of BSA within the immersed solutions using BCA kit.

2.3.4. In vitro mineralization

The bioactivity and bone bonding capacity of the obtained samples was investigated by apatite formation in simulated body fluid (SBF) for 21 days. The SBF solution was prepared according to the protocol developed by Kokubo et al. [29]. Square films with size of 2 × 2 cm2 were incubated in 30 mL SBF solution in a centrifuge tube at 37 °C and refreshed every 3 days. After immersion, the specimens were gently rinsed with deionized water and freeze dried. After sputter coated with gold, surface morphology and chemical composition of mineral deposits were characterized by SEM and EDX.

2.4. Compressive mechanical properties

As PEEK implants mainly bore compressive stress after implantation, in this study, the compressive mechanical property of the different samples was evaluated according to the National Standard of China (GB/T1039). The compressive mechanical properties of various samples with size of 30 × 10 × 10 mm3 were measured by a universal mechanical testing machine (Instron 1121, UK) with speed of 2 mm/min at room temperature. For each group five duplicate specimens were tested and the compression data were collected.

2.5. In vitro cell studies

2.5.1. Cell culture

Cell experiments were performed by using mouse pre-osteoblast cells (MC3T3-E1) purchased from Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Cells were cultivated in a complete cell culture medium comprising a mixture of Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Before cell culturing, all the samples were sterilized with 75% alcohol for 40 min and rinsed with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) thrice. The medium for cell culture was refreshed every other day.

2.5.2. Cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity of the different samples was evaluated by culturing MC3T3-E1 cells in extraction liquids following the National Standard of China GB/T 16886. Briefly, the samples with total area of 6 cm2 were immersed in 1 mL medium at 37 °C and extracted for 24 and 72 h respectively. MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 8 × 103 cells per well. After 24 h of incubation, the medium was replaced with 200 μL/well of the extraction liquids. After culturing for 24 h, 20 μL CCK-8 was added into each well, and the incubation was kept for another 2 h and the optical density was determined at 450 nm (Tecan Infinite M200). The complete cell culture medium were used as a control group. The cytotoxicity of the samples were expressed as cell viability ratio, which was calculated by the following equation:

| Cell viability (%) = OD values (Samples)/OD values (Blank) |

2.5.3. Cell adhesion

MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded on each samples in 24 well tissue culture plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well followed by culturing for 12 and 24 h. Afterwards, the cell seeded samples were rinsed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA. The nuclei were stained with DAPI and counted at least five independent areas using fluorescence microscopy (TE2000U, Nikon, Japan) for quantitative analysis.

2.5.4. Cell proliferation

CCK-8 assay was employed to quantitatively determine the proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells on the samples. Cells were seeded on each sample in the 24-well tissue culture plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and cultured for 1, 3 and 7 days. At every prescribed time point, 30 μL/well CCK-8 solution was added to the well. After 2 h of incubation, 200 μL of the medium was transferred to a 96-well plate for measurement. The absorbance was determined at 450 nm using a multifunctional micro-plate scanner (Tecan Infinite M200).

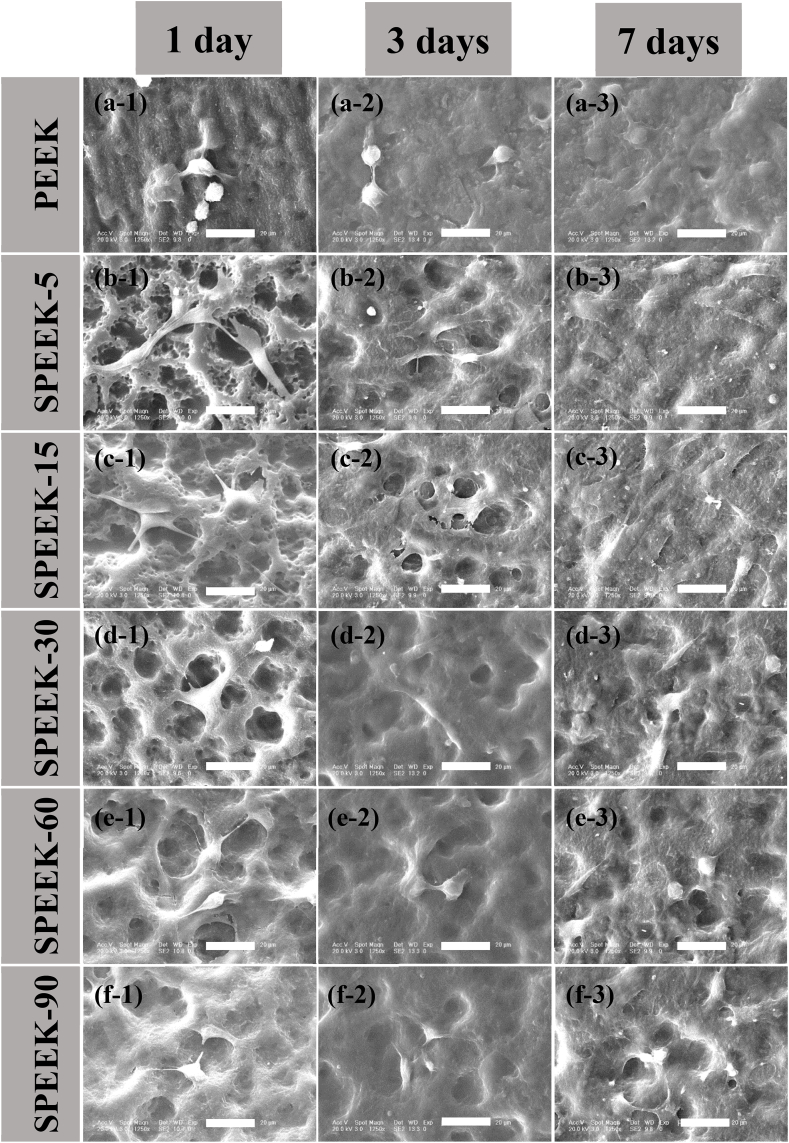

2.5.5. Cell morphology and extracellular matrix secretion

Cell morphology and extracellular matrix secretion of MC3T3-E1 grown on the different samples was visualized by SEM. Briefly, MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured on the different substrates with an initial seeding density of 2 × 104 cells/well. After cultured for 1, 3 and 7 days, the samples with cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the cells were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol (50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90% and 100%) for 30 min, respectively. Finally, the critically dried samples were sputtered with gold and examined under SEM.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All the data were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). Independent and replicated experiments were used to analyze the statistical variability of the data. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Imaging data were analyzed using Origin 8.5 software.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Surface characterization

3.1.1. Chemical characterization

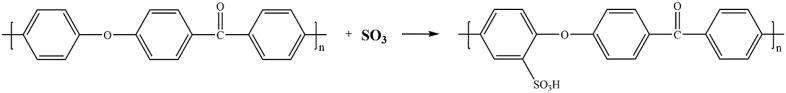

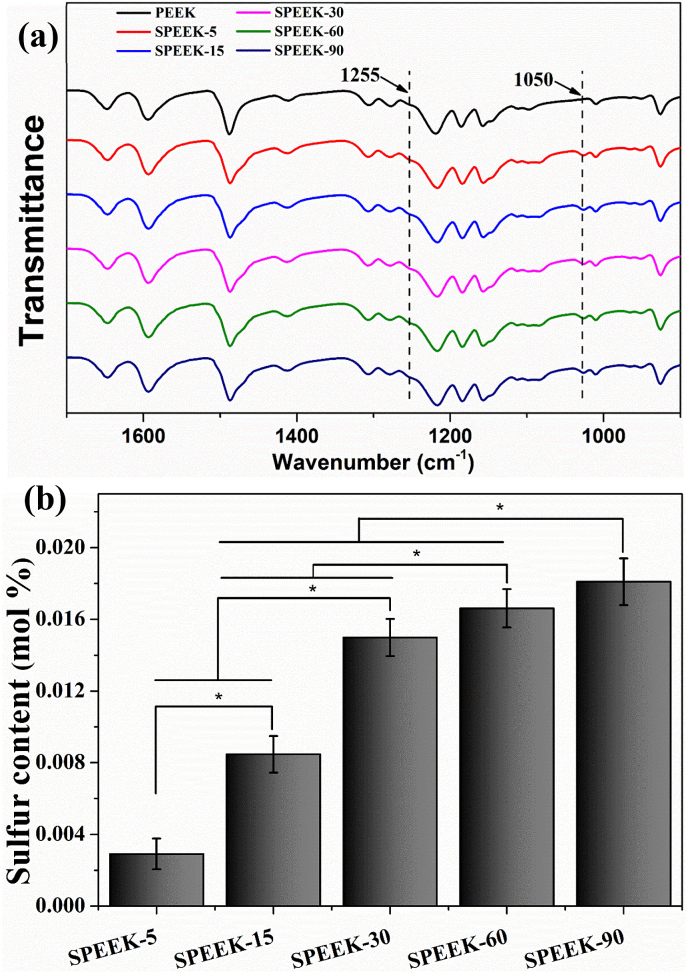

Fig. 2 (a) showed the FT-IR from 1700 cm−1–900 cm−1 of different samples. In the spectra all the characteristic bands were presented, including the diphenylketone bands at 1650 cm−1, 1490 cm−1 and 926 cm−1, C–O–C stretching vibration of the diaryl groups at 1188 cm−1 and 1158 cm−1, as well as a peak at 1600 cm1 related to C C of the benzene ring in PEEK. After sulfonation by gaseous SO3, the specific peak of sulfonated PEEK including dissymmetric stretching of O S O and S O could be detected at 1255 cm−1 at 1050 cm−1, respectively. The data demonstrated that –SO3H groups were introduced to the PEEK surface by gaseous SO3 sulfonation.

Fig. 2.

(a) FT-IR spectra of the signal at 1255 cm−1 and 1050 cm−1 represented O S O dissymmetric stretching and S O symmetric stretching, respectively. (b) The surface sulfur content of the samples with various sulfonating time detected by EDX.

The sulfur elemental composition was evaluated by EDX and represented as quantitative of –SO3H groups during different sulfonation time. The surface sulfur element was summarized as showed in Fig. 2 (b). It could be observed that sulfur content was variations versus sulfonation time. The surface sulfur content was 0.003 ± 0.0006 mol % for SPEEK-5 and it was increased to 0.008 ± 0.001 mol %, 0.015 ± 0.001 mol %, 0.017 ± 0.001 mol % and 0.018 ± 0.001 mol % for SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90, respectively. The results demonstrated that more sulfur functional groups (-SO3H) was introduced to the surface of PEEK films with increasing sulfonation time.

3.1.2. Surface morphology and porous structure analysis

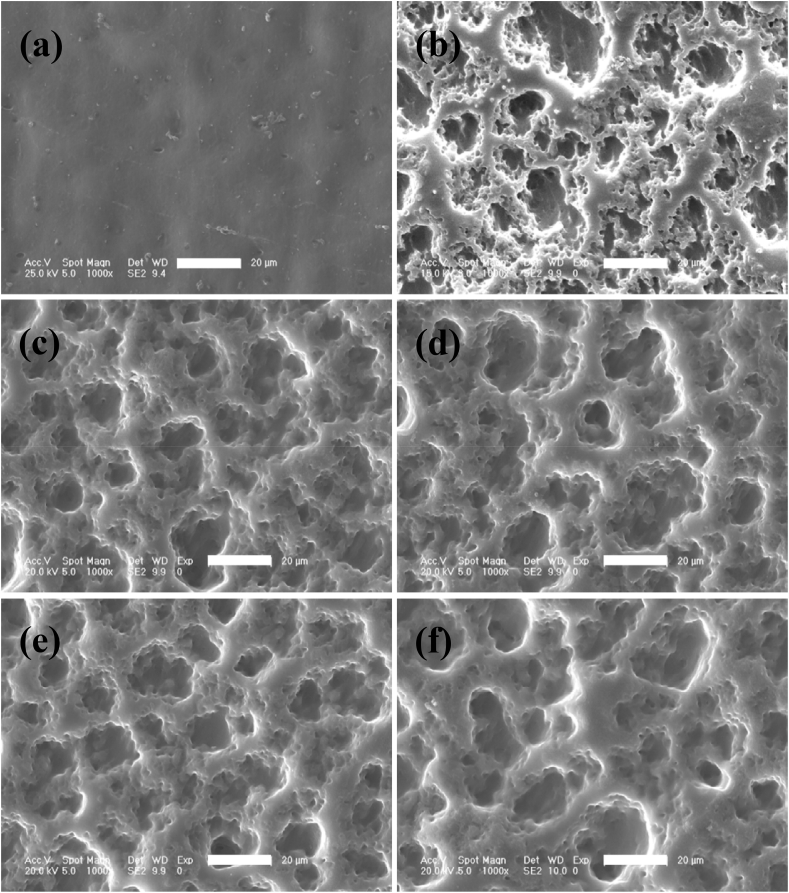

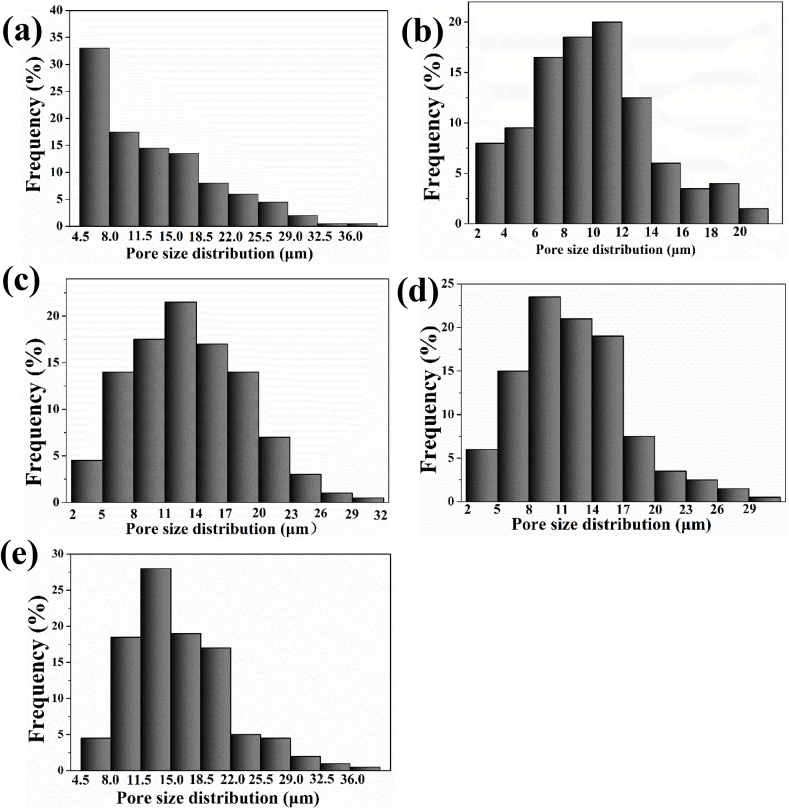

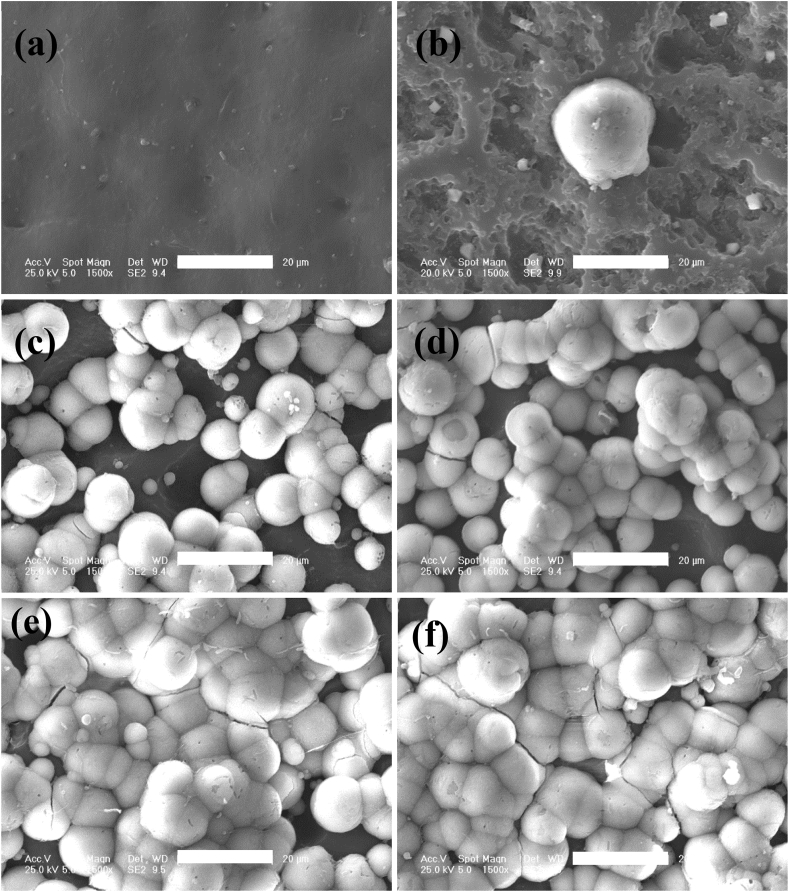

The surface morphology (Fig. 3 a-f) and size distribution of micro-pores (Fig. 4 e-f) was characterized by SEM and analyzed with image J software. Porous structure with different size of irregular pores distributing from 4.5 to 18.5 μm was appeared on the surface of SPEEK-5 (Fig. 3 b) compared with smooth morphology of pure PEEK (Fig. 3 a). After sulfonating for 15 min, more uniform porous morphological structure was observed on the surface of SPEEK-15 (Fig. 3 c) and the size distribution was mainly from 6 to 14 μm (Fig. 4 b). As showed in Fig. 3 d-f and Fig. 4 c-e, as sulfonating for more than 15 min, the morphology of SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 was similar with that of SPEEK-15 showing uniform porous structure and most of the micro-pores were distributed from 8 to 20 μm.

Fig. 3.

SEM images showing the surface morphological features of PEEK (a), SPEEK-5 (b), SPEEK-15 (c), SPEEK-30 (d), SPEEK-60 (e) and SPEEK-90 (f). All scale bar lengths are 20 μm.

Fig. 4.

Micro-pore size frequency distribution of SPEEK-5 (a), SPEEK-15 (b), SPEEK-30 (c), SPEEK-60 (d) and SPEEK-90 (e) measured by Image J software.

The BET specific surface area, meso-pore volume and meso-pore size of the different samples were evaluated by N2 adsorption desorption measurement and the data were collected in Table 1. It could be detected that average meso-pore volume of SPEEK-5, SPEEK-15 and SPEEK-30 was increased from 0.007 cc/g, 0.009 cc/g to 0.017 cc/g and meso-pore size was increased from 2.382 nm, 2.600 nm–2.838 nm with prolong of surface sulfonating time. However, the meso-pore volume and meso-pore size for SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 were the same (0.019 cc/g and 2.838 nm) which was similar with that of SPEEK-30 samples. These results indicated that micro-pore and meso-pore parameters increased with the prolonged sulfonating time up to 30 min. Therefore, due to the increasing size of micro-pore and meso-pore, the BET specific surface area of SPEEK-5, SPEEK-15 and SPEEK-30 films increased from 3.406 m2/g, 7.607 m2/g to 7.990 m2/g. Furthermore, both the micro-pore and meso-pore size did not change any more even if the sulfonating time was prolonged up to 60 or 90 min. It was interesting to note that the specific surface area decreased as surface sulfonation for 30 min to 90 min.

Table 1.

BET specific surface area, meso-pore volume and meso-pore size evaluated by N2 adsorption desorption measurement.

| Samples | Surface area (m2/g) | Pore volume (cc/g) | Pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPEEK-5 | 3.406 | 0.007 | 2.382 |

| SPEEK-15 | 7.607 | 0.009 | 2.600 |

| SPEEK-30 | 7.990 | 0.017 | 2.838 |

| SPEEK-60 | 7.463 | 0.019 | 2.838 |

| SPEEK-90 | 7.340 | 0.019 | 2.838 |

From the results of surface chemical and morphology characterization, it was found that porous structure could be generated on the surface of PEEK films by the sulfonation process with SO3 and a thin layer of sulfonated PEEK exhibited bouffant state. It indicated that the chain conformation of PEEK has been destroyed and the original compact structure was tailored by sulfonation. After washing with deionized water, highly sulfonated PEEK would diffuse into water and a porous structure was thus formed. A similar phenomenon has also been reported that surface sulfonation could promote the formation of porous structure on the surface of PEEK materials by concentrated sulfuric acid [22]. What's more, the results also showed that surface porous morphology and sulfur content were undoubtedly influenced by different sulfonating time. After treated with gaseous SO3 for 5 min, inadequate sulfonation resulted in irregular surface morphology for SPEEK-5 films. While after sulfonating for more than 15 min, the surface micro-topology of SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 samples showed similar uniform porous structure compared with irregular porous structure of SPEEK-5. It might be attributed to sulfonated PEEK had been produced on the whole surface area of PEEK films and removed by washing with deionized water resulting in porous morphology. The different appearance of surface porous structure on the PEEK films was caused by sulfonating depth of SPEEK for more than 15 min. The highest level of micro-pore size, meso-pore size, meso-pore volume and specific surface area was observed for the SPEEK-30 groups. After sulfonating for 60 and 90 min, the specific surface area decreased compared with SPEEK-30 while the micro-pore and meso-pore size did not change any more. It might be related to the integration among meso-pores or meso-pores with micro-pores as sulfonating for more than 30 min and the decreased of meso-pores would reduce the specific surface area [30].

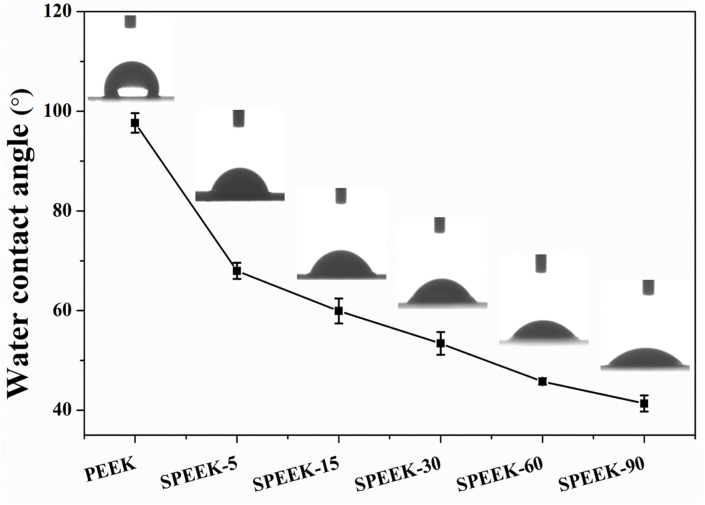

3.1.3. Water contact angle analysis

After evaluating the surface porous morphology of various samples and confirming the introduction of –SO3H groups on the surface of SPEEK materials. The water contact angle of all the samples was measured and the results were shown in Fig. 5. The water contact angle of pure PEEK was 97.70° ± 1.96° and it decreased to 67.97° ± 1.63° after sulfonating for 5 min (SPEEK-5). The surface of SPEEK samples became more hydrophilic as the water contact angle decreased to 59.9° ± 2.5°, 53.4° ± 2.3°, 45.8° ± 3.6° and 41.4° ± 1.6° for SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Water contact angle of different samples measured by the static sessile drop method. p < 0.05, n = 5.

Previous studies has reported that the surface morphology and introduction of –SO3H groups would influence the surface hydrophilicity in various degrees [31]. Mahjoubi et al. [32] reported that sandblasted PEEK materials was more hydrophobic than polished PEEK due to its rough surface. In addition, the results in Bo's study [14] also showed that the introduction of –SO3H groups on PEEK surface would enhance hydrophilicity. The finding of this study implied that the topological morphology and incorporation of –SO3H groups played a key role in improving the surface hydrophilicity of PEEK substrates.

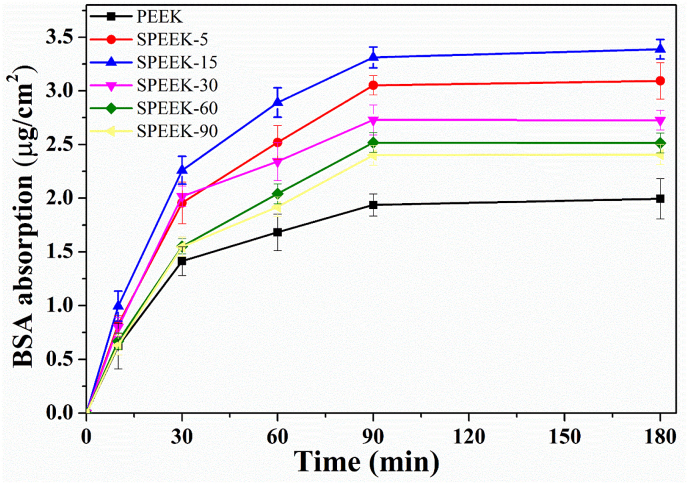

3.1.4. Protein adsorption

Protein adsorption on the surface of implants was a crucial process for cell/implant interaction and would determine the cellular response on biomaterial surface [33]. After implantation, biomaterials will contact with body fluid and protein adsorption will take place on the biomaterial interfaces. Cell interaction with the adsorbed protein layer can be observed on the surface of implants [34,35]. The evaluation of proteins interacted with implants could demonstrate the correlation between biomaterials and human tissues at the defect site.

As shown in Fig. 6 the maximum amount of BSA protein absorbed on PEEK, SPEEK-5, SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 was 1.99 μg/cm2, 3.09 μg/cm2, 3.39 μg/cm2, 2.73 μg/cm2, 2.51 μg/cm2, 2.41 μg/cm2, respectively. The protein adsorption capacity of SPEEK-5 and SPEEK-15 was significant improved with 1.55 and 1.70 folds due to the increased specific surface area compared with pure PEEK. However, the absorption capacity of SPEEK-30 decreased although it had a higher specific surface area and the absorption capacity was further decreased for SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90. Comparing to SPEEK-15, the reduction of absorption capacity for SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 was 19.5%, 25.8% and 28.95% respectively.

Fig. 6.

Time-dependent BSA adsorption capacity of various samples from 5 min to 180 min. The concentration of BSA solution: 0.5 mg/mL, pH = 7.35, temperature: 37 °C.

Generally, the protein absorption capacity mainly depends upon the surface physical and chemical properties of the biomaterials [28]. According to previous reports [36], the specific surface area played a crucial role for physical properties on protein absorption capacity. Our results showed that the protein absorption capacity of all the samples enhanced due to the increased specific surface area. However, the protein absorption capacity decreased after sulfonating for more than 15 min and it might be due to the repulsive interaction between an increasing amount of negative –SO3H groups and acidic BSA protein. As the isoelectric point of BSA was 4.7, when it was dissolved in PBS (pH = 7.35) the net charge of BSA solution was negative (BSA−). Thereby negative –SO3H groups on the surface of PEEK materials would generate electrostatic repulsion with BSA− at the interface of PEEK/protein. The increased amount of negative –SO3H groups with sulfonating time as previous described resulted in electrostatic repulsion force. Even if SPEEK-15 exhibited lower surface area than SPEEK-30, inferior electrostatic repulsion interaction on the interface of SPEEK-15/BSA− induced higher protein absorption capacity than SPEEK-30.

3.1.5. In vitro mineralization

As shown in Fig. 7 a, there was no apparent observation of apatite deposition on the surface of pure PEEK. It could be observed that a spot of globular shaped apatite aggregation was observed on the surface of SPEEK-5 (Fig. 7 b). In contrast, much more apatite aggregation was appeared for SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 samples (Fig. 7 c-f). Most of all, almost the entire surface of SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 samples was covered by a dense layer of apatite crystals. The EDX analysis was processed to analyze chemical element content of the precipitates on the samples surface and the results were summarized in Table 2. It demonstrated that the formed particles contained calcium (Ca) and phosphorous (P) and the Ca/P ratio was about 1.64, which was approximate to that of bone mineral.

Fig. 7.

SEM micrographs of various samples after soaking in SBF for 21 days: PEEK (a), SPEEK-5 (b), SPEEK-15 (c), SPEEK-30 (d), SPEEK-60 (e) and SPEEK-90 (f). All scale bar lengths are 20 μm.

Table 2.

The Ca/P ratio of apatite deposition on various specimens after immersion in SBF for 21 days evaluated by EDX.

| SPEEK-5 | SPEEK-15 | SPEEK-30 | SPEEK-60 | SPEEK-90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca (mol) | 0.787 ± 0.065 | 0.782 ± 0.044 | 0.684 ± 0.037 | 0.738 ± 0.032 | 0.669 ± 0.042 |

| P (mol) | 0.480 ± 0.041 | 0.475 ± 0.025 | 0.418 ± 0.020 | 0.450 ± 0.027 | 0.405 ± 0.032 |

| Ca/P | 1.640 ± 0.022 | 1.640 ± 0.013 | 1.640 ± 0.009 | 1.640 ± 0.017 | 1.650 ± 0.019 |

According to previous studies, the formation ability of apatite on the matrix surface could express the bioactivity of biomaterial and potentially lead to in vivo bone bonding [37]. The results of our study showed that apatite could be formed on the surface of SPEEK materials by soaking into SBF and it indicated that surface mineralization ability of sulfonated PEEK using gaseous SO3 was significantly improved. In addition to the improvement of topological structure of SPEEK materials, the mechanism of enhanced mineralization ability could be mainly attributed to electrostatic interaction of negative –SO3H groups with Ca2+ ions in SBF solution. Considering the ionic nature, the electrostatic interaction between –SO3H groups and Ca2+ ions triggered initial nucleation, and the present of positive Ca2+ might play a pivotal part in anchoring phosphate and hydroxyl ions. With the accumulation of Ca2+ ions, negatively charged ions (HPO42− and OH−) in the SBF were incorporated onto the surfaces of SPEEK substrates leading to the formation of a hydrated precursor cluster consisting of calcium hydrogen phosphate.

3.2. Mechanical properties

The compressive mechanical properties of the samples with various sulfonating time were displayed in Table 3. The initial compressive strength of the pure PEEK was 124.2 ± 2.7 MPa. After surface modified by gaseous SO3, the compressive strength was 123.4 ± 1.6, 123.2 ± 5.5, 123.2 ± 2.8, 122.8 ± 2.8 and 121.4 ± 2.4 MPa for SPEEK-5, SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90, respectively. A similar slightly decrease tendency was observed in compressive modulus and ultimate breaking point energy. Compared with pure PEEK, compressive modulus was slightly decreased with increasing sulfonation time and the maximum reduction was merely 1.83% for SPEEK-90. The influence of ultimate breaking point energy by the surface modification was evaluated and the results showed that changes could be negligible as the reduction was merely 1.57%, 1.98%, 2.22%, 3.12%, and 4.25% for SPEEK-5, SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90, respectively.

Table 3.

Compressive mechanical properties of pure PEEK and samples sulfonated by gaseous SO3 for different time, including compressive strength (CS), compressive modulus (CM) and ultimate breaking point energy (UBPE) for each group.

| Samples | CS (MPa) | CM (MPa) | UBPE (mJ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEEK | 124.2 ± 2.7 | 2954 ± 40.9 | 69600.5 ± 1368.1 |

| SPEEK-5 | 123.4 ± 1.6 | 2952 ± 86.1 | 68509.9 ± 691.8 |

| SPEEK-15 | 123.2 ± 5.5 | 2926 ± 74.5 | 68058.7 ± 1247.9 |

| SPEEK-30 | 123.2 ± 2.8 | 2922 ± 23.9 | 67430.3 ± 1033.2 |

| SPEEK-60 | 122.8 ± 2.8 | 2916 ± 41.6 | 68224.3 ± 1175.3 |

| SPEEK-90 | 121.4 ± 2.4 | 2900 ± 68.9 | 66639.5 ± 1209.5 |

Currently, most of studies for PEEK surface modification focused on sulfonation process by immersing in concentrated sulfuric acid to overcome the inherent chemical and physical inertness [22,38,39]. However, dissolution of PEEK would be rapidly occurred during immersing in concentrated sulfuric acid and inevitable decrease of mechanical strength made it difficult for application in clinical treatment. And the obtained results in this study showed that the compressive mechanical properties of PEEK implants were not influenced by the surface modification with gaseous SO3. It also implied that the sulfonation process by using gaseous SO3 for the generating of porous structure and incorporation of –SO3H group on the surface of PEEK could preserve the original mechanical performance of PEEK materials to the greatest extent predicting that it might be suitable for application in the orthopedics.

3.3. Cell culture of SPEEK

3.3.1. Cytotoxicity

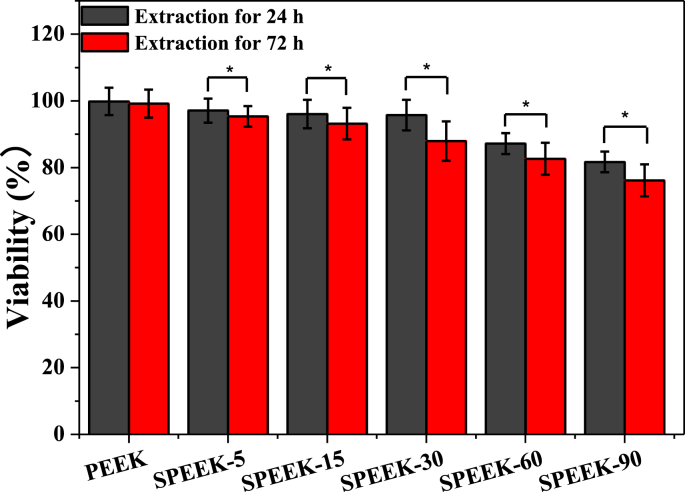

The cytotoxicity of modified SPEEK implants was performed by culturing MC3T3-E1 cells with the extraction liquids. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the cell viability of pure PEEK was 99.82% and 99.18% for extracting of 24 h and 72 h, respectively. However, cell viability decreased for all the SPEEK materials. Cell viability of SPEEK-5, SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60, SPEEK-90 was 97.08%, 96.03%, 95.71%, 87.18%, 81.68% for 24 h extraction assay and 95.35%, 93.18%, 87.95%, 82.63%, 76.15% for 72 h extraction assay. The decreasing tendency for cell viability was in accordance with sulfonating time from 5 to 90 min in both 24 and 72 h extraction assay. Moreover, cell viability of 72 h extraction assay was significantly lower than that of 24 h with statistical difference (p < 0.05) for all the SPEEK groups, demonstrating that the SPEEK samples with higher sulfonation ratio exhibited cytotoxicity due to higher degree of –SO3H groups on the samples.

Fig. 8.

In vitro cytotoxicity of various samples evaluated by 24 h and 72 h indirect extraction liquids assay and expressed as cell viability. p < 0.05, n = 3.

The cytotoxicity of the extracts might mainly dependent on sulfocompounds content in the extracted liquid which was attributed to both surface sulfur content on the SPEEK surface and the extracting time. Previous results have shown that surface sulfur functional groups (-SO3H) increased with the prolongation of sulphonating time [40]. It was found that the sulfur functional groups (-SO3H) on the surface of sulfonated PEEK would release in deionized water by the hydrothermal treatment and residual sulfur groups showed negative influence to cell proliferation. Therefore, desulfonation reaction would be slowly generated at the environment of extration liquid assay (37 °C, cell culture medium) and sulfocompounds released into extraction liquid showed cytotoxicity behavior. Thus, more sulfocompounds would release in the groups with higher sulfonation ratio and showed an obviously cytotoxicity behavior.

3.3.2. Cell adhesion

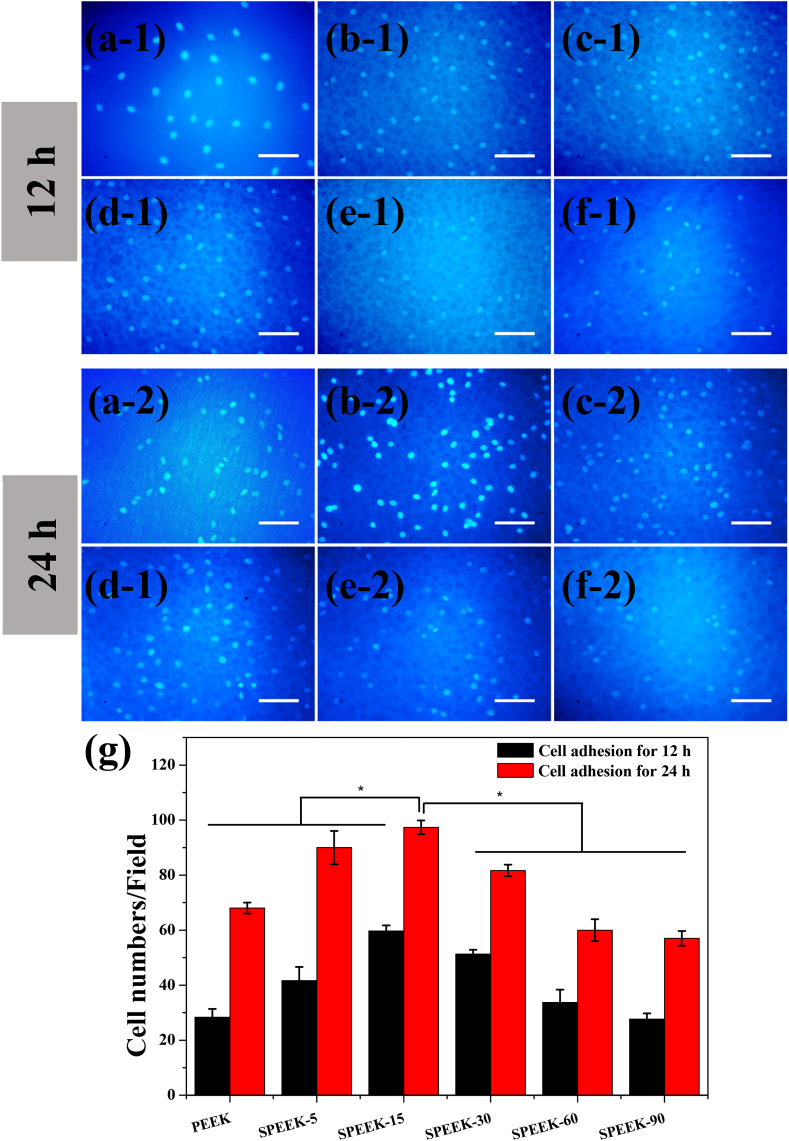

The viable MC3T3-E1 cells adhered on the samples after 12 h incubation was shown in Fig. 9 a-1 to f-1. The adherent cell numbers on SPEEK-5 was more than that of PEEK sample. Previous studies have demonstrated that porous structure could provide attachment point and enhance adhesion of pre-osteoblast cells [41]. Moreover, it could be detected that the number of adherent cells on the surface of SPEEK-15 was obvious increased compared with SPEEK-5. It would be attributed to the uniform surface morphology and the surface pore size was more compatible for cell attachment. However, cell adhesion on SPEEK-30 films decreased although it showed similar surface morphology and micro-pore size distribution with SPEEK-15. Moreover, adhered cell numbers was further decreased for SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90, indicating excessive surface sulfur groups (-SO3H) might have negative effective for cell adhesion.

Fig. 9.

Cell adhesion on the various samples after incubation for 12 and 24 h: PEEK (a-1 and a-2), SPEEK-5 (b-1 and b-2), SPEEK-15 (c-1 and c-2), SPEEK-30 (d-1 and d-2), SPEEK-60 (e−1 and e−2) and SPEEK-90 (f-1 and f-2). All scale bar lengths are 100 μm. (g): Average cell number of MC3T3-E1 counted on three different samples for each group. p < 0.05, n = 5.

To rigorously investigating cell adhesion on the various samples, cell adhesion assay for 24 h was also approached and the results were shown in Fig. 9 a-2 to f-2. Adherent cell numbers increased with increasing culture time, indicating cells formed stable adhesion on the sample surface. Adhered cells on SPEEK-5 increased due to appearance of porous structure and more adherent cells were founded for SPEEK-15 group which was corresponding to cell adhesion at 12 h. A similar decreasing trend of attached cell number with increased of surface sulfur content was also found for 24 h cell adhesion assay. The results of cell adhesion at 12 and 24 h demonstrated that SPEEK-15 was more suitable for cell adhesion than the other groups.

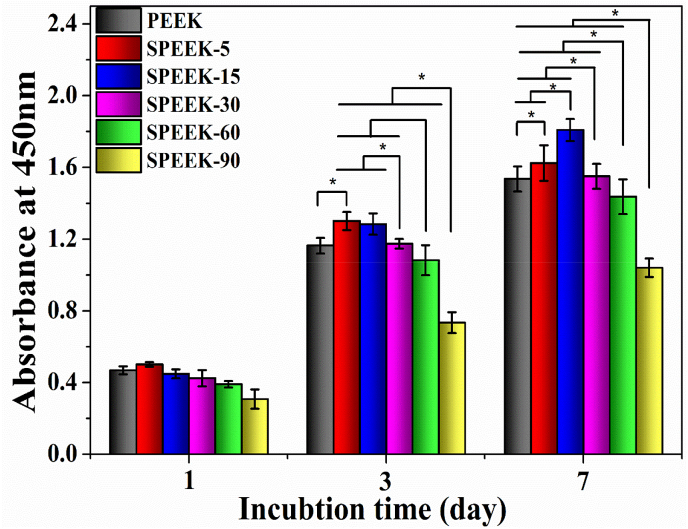

3.3.3. Cell proliferation

The proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells on the different samples after culturing for 1, 3 and 7 days was shown in Fig. 10. It could be found that the OD values increased with increasing culture time, showing promotion of pre-osteoblasts proliferation. After culturing for 3 and 7 days, SPEEK-5 exhibited higher OD values than pure PEEK. The cell proliferation for SPEEK-15 groups was significantly enhanced showing similar OD values compared with SPEEK-5 at 3 days while higher OD values was observed at 7 days. Previous studies had reported [42] that porous structure was advantageous for cell adhesion and proliferation, thus OD values of SPEEK-5 and SPEEK-15 samples was significant increased. However, due to the high content of surface –SO3H groups cell proliferation of SPEEK-15 would negatively influenced by the cytotoxicity of –SO3H group at 3 days. Then, sulfur content on the SPEEK-15 surface would decrease as the sulfocompounds released into the cell culture medium. Consequently, cell proliferation of SPEEK-15 was obviously improved at 7 days as the uniform surface morphology and pore size provided a favorable environment for promoting cell attachment and proliferation. Notably, OD values of SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 was significantly lower than SPEEK-15 although they exhibited similar surface morphology because higher content of surface –SO3H group would detrimental to cell proliferation.

Fig. 10.

Cell proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cultured on PEEK, SPEEK-5, SPEEK-15, SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 for 1, 3 and 7 days evaluated by CCK-8 assay. p < 0.05, n = 3.

3.3.4. Cellular morphology and extracellular matrix (ECM)

MC3T3-E1 cellular morphology was directly observed by SEM after culturing for 1, 3 and 7 days. As displayed in Fig. 11 a-1 to f-1, cell spreading morphology differed greatly on various sample surfaces at 1 day. MC3T3-E1 cells adhered on pure PEEK exhibited spheroid shape and no clear lamellipodia extension was found (Fig. 11 a-1), which was the characteristic of original pre-osteoblast morphology, demonstrating bio-inert of the pure PEEK surface. It could be observed that cells adhered on SPEEK-5 (Fig. 11 b-1) were found to be transforming from spheroid shape to thread spindles and partly adhered across porous structure. Fig. 11 c-1 showed that cells adhered on SPEEK-15 had been acquired their typical flat morphology with highly elongation and more filopodia protrusions were detected. Moreover, it could also be observed that pre-osteoblasts spread along the inner wall of the SPEEK-15 porous structure with their well-extended lamellipodia and filopodia. The results indicated that biocompatibility of SPEEK-15 was significantly enhanced due to their excellent pore size and low sulfur content which could favor the entrance of pre-osteoblast cells. The SEM images of MC3T3-E1 cells grown on SPEEK-30 (Fig. 11d–1) showed that cells partly adhered on the pores with their lamellipodia and gradually transformed from spheroid shape to flat. Fig. 11 e−1 and f-1 showed spheroid shaped cells adhered on SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 demonstrated an inferior cell spread status and unhealthily attachment on the samples surface.

Fig. 11.

SEM images of the cell morphology and extracellular matrix secretion of MC3T3-E1 cultured on different samples for 1, 3 and 7 days: PEEK (a-1, a-2 and a-3), SPEEK-5 (b-1, b-2 and b-3), SPEEK-15 (c-1, c-2 and c-3), SPEEK-30 (d-1, d-2 and d-3), SPEEK-60 (e−1, e−2 and e−3) and SPEEK-90 (f-1, f-2 and f-3). All scale bar lengths are 20 μm.

MC3T3-E1 cellular morphology after culturing for 3 days was shown in Fig. 11 a-2 to f-2. MC3T3-E1 cells grown on the bio-inert PEEK surface still remained spheroid shape and a modicum ECM was found (Fig. 11 a-2). Most of cells grown on SPEEK-5 and SPEEK-15 exhibited higher elongation ratios and more filopodia protrusions in an excellent spreading statue (Fig. 11 b-2 and c-2). Moreover, ECM covered almost the entire surface with their elongated sheet like morphology, implying healthily growth of the cells on the surface of SPEEK-5 and SPEEK-15. Fewer cells adhered on higher sulfur content samples (SPEEK-30, SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90) and showed seldom filopodia, spindle shaped morphology and inferior spreading status (Fig. 11 d-2 to f-2).

Cellular morphology and ECM secretion was differed greatly after cultured for 7 days as shown in Fig. 11 a-3 to f-3. MC3T3-E1 cells grown on pure PEEK had been spread from spheroid shape to flat round state, but some cells with fabiform morphology could still be observed (Fig. 11 a-3). In contrast remarkably, a dense layer of cells featuring numerous filopodial and lamellipodial extension was covered on the surface of SPEEK-5 and SPEEK-15 shown in Fig. 11 b-3 and c-3. In addition, cells were almost buried in ECM and multilayer cell sheets covered the entire surface with their elongated sheet like morphology. As shown in Fig. 11 d-3, most of cells grown on SPEEK-30 still exhibited spindle shape, but higher elongation ratios and more filopodia protrusions appeared. Cellular morphology of SPEEK-60 and SPEEK-90 still showed fabiform morphology (Fig. 11 e−3 and f-3). In this section, cellular spreading and ECM secretion was systematically investigated after cultured for 1, 3 and 7 days, the results demonstrated that SPEEK-5 and SPEEK-15 provided excellent surface property for pre-osteoblasts cells growth and hence osseointegration capacity might be enhanced consequently.

Our in vitro study showed that cell adhesion, spreading, proliferation and ECM secretion had significant difference for the various samples. Cellular response was obviously enhanced by porous structure while suppressed by higher content of –SO3H groups. The cytocompatibility of SPEEK-5 was superior to the pure PEEK due to generation of porous structure and lower sulfur content despite the irregular pore size distribution. The bioactivity and osseointegration of SPEEK-15 was mostly enhanced compared with other groups as uniform surface morphology, suitable pore size and appropriate sulfur content. Then, the negative effective of cell response was gradually remarkable with increase of surface –SO3H groups. Previous studies had various opinion for the negative cell response of –SO3H group on the sulfonated PEEK. In a study reported by Zhao et al. [22], porous structure was produced on PEEK surface by concentrated sulfuric acid and subsequent water immersion. Acetone was utilized to reduce residual sulfuric acid from the porous surface. Their results demonstrated that residual sulfuric acid on the surface porous structure provided a low pH environment for cell adhesion and proliferation and might decrease the cytocompatibility of PEEK materials. Concentrated sulfuric acid was also utilized to fabricate the porous structure on PEEK surface in Ouyang's study [40] and a subsequent hydrothermal treatment was applied to remove the residual sulfur from the surface. Their study showed that samples with higher sulfur content would decrease proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of rBMSCs in vitro and revealed that the oxygen free radicals produced by sulfocompounds might damage cells and DNA transcription.

Surface morphology and chemical composition are crucial for biomedical material because they will directly influence initial interactions between cells and implant surface [43]. Initial cell adhesion is usually responsible for ensuring cell functions and consequently increase cell spreading and proliferation [44]. Hence, better adhesion and proliferation of osteoblasts probably produce a larger mass of new bone formation on the interface of implants/tissue and more robust bone/implant bonding is also expected in vivo [45]. Previous study had reported that micro-pore could enhance cell adhesion, proliferation of pre-osteoblasts and neo-vascularization [46]. While meso-pores provided larger surface area in favor of protein adsorption and ion exchange for apatite formation and affect the osteogenesis in an indirect way [30]. In this study, a porous micro-architecture with micro-pore and meso-pore on the surface of PEEK implants was successfully fabricated by this novel surface modification approach and the results showed that protein adsorption capacity, in vitro mineralization, cell adhesion, spreading, proliferation and ECM secretion was obvious improved for SPEEK-15 samples.

In recent years, biological modification of PEEK implants had been attracted considerable attention in tissue engineering applications. In previous studies [10,14,47], the surface porous structure and fully three dimensionally porous structure was fabricated to enhance the bioactive of PEEK implant. However, the porous structures generated by those methods would reduce the mechanical strength of PEEK implants and it could not meet the demand of clinical applications. In contrast, the superiority of this novel approach was that high mechanical strength of PEEK materials could be maintained for biomedical applications. Moreover, the integrity of the PEEK materials could also be preserved by this novel modification approach. Classical PEEK modification approach such as plasma spray [48], concentrated sulfuric acid immersion method [38] or sandblasting [23] would result in deformation of polymer and physical shape of the PEEK implants might be distorted by those approaches. And it does not meet the aim of clinical application properly. Last but not the least, as the superior dispersivity of the gaseous state of SO3 this novel modification approach could be easily applied to PEEK implants with complex geometry.

4. Conclusion

In all, a novel controllable sulfonation strategy using gaseous SO3 was developed for bioactivation of PEEK implants with surface porous microstructure and incorporation of –SO3H component preserving their initial compressive mechanical properties for bearing physiological stress. SEM analysis showed that SPEEK samples exhibited similar surface topological morphology after sulfonating for more than 15 min. Together with the introduction of –SO3H groups on the porous surface, mineral apatite deposition capacity was remarkably improved. Protein absorption ability was significant improved for SPEEK-15 group due to generated porous microstructure and moderate content of –SO3H group. In vitro cellular response of cell adhesion, spreading proliferation as well as ECM secretion was significantly enhanced for SPEEK-15 films. Finding from this study demonstrated that potential application of SPEEK-15 was more promising in orthopedics due to the excellent cytocompatibility and bioactivity.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Teng Wan: Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Zixue Jiao: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation. Min Guo: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation. Zongliang Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Yizao Wan: Methodology, Visualization. Kaili Lin: Methodology, Visualization. Qinyi Liu: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Peibiao Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Projects. 51673186 and 81672263) and the Special Fund for Industrialization of Science and Technology Cooperation between Jilin Province and Chinese Academy of Sciences (2017SYHZ0021).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Contributor Information

Zongliang Wang, Email: wangzl@ciac.ac.cn.

Qinyi Liu, Email: 1226527208@qq.com.

Peibiao Zhang, Email: zhangpb@ciac.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Liu X.Y., Chu P.K., Ding C.X. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications. Mater Sci Eng R. 2004;47:49–121. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz S.M., Devine J.N. PEEK biomaterials in trauma, orthopedic, and spinal implants. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4845–4869. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao Y., Wong S.M., Wong H.M., Wu S.L., Hu T., Yeung K.W.K., Chu P.K. Effects of carbon and nitrogen plasma immersion ion implantation on in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of titanium alloy. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2013;5:1510–1516. doi: 10.1021/am302961h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L.X., He S., Wu X.M., Liang S.S., Mu Z.L., Wei J., Deng F., Deng Y., Wei S.C. Polyetheretherketone/nano-fluorohydroxyapatite composite with antimicrobial activity and osseointegration properties. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6758–6775. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J.H., Jang H.L., Lee K.M., Baek H.R., Jin K., Hong K.S., Noh J.H., Lee H.K. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the bioactivity of hydroxyapatite-coated polyetheretherketone biocomposites created by cold spray technology. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6177–6187. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godara A., Raabe D., Green S. The influence of sterilization processes on the micromechanical properties of carbon fiber-reinforced PEEK composites for bone implant applications. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh W.R., Pelletier M.H., Christou C., He J.W., Vizesi F., Boden S.D. The in vivo response to a novel Ti coating compared with polyether ether ketone: evaluation of the periphery and inner surfaces of an implant. Spine J. 2018;18:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu S.D., Zhu Y.T., Gao H.N., Ge P., Ren K.L., Gao J.W., Cao Y.P., Han D., Zhang J.H. One-step fabrication of functionalized poly(etheretherketone) surfaces with enhanced biocompatibility and osteogenic activity. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater. 2018;88:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastan F.E., Rehman M.A.U., Avcu Y.Y., Avcu E., Ustel F., Boccaccin A.R. Electrophoretic co-deposition of PEEK-hydroxyapatite composite coatings for biomedical applications. Colloids Surf., B. 2018;169:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn H., Patel R.R., Hoyt A.J., Lin A.S.P., Torstrick F.B., Guldberg R.E., Frick C.P., Carpenter R.D., Yakacki C.M., Willett N.J. Biological evaluation and finite-element modeling of porous poly(para-phenylene) for orthopaedic implants. Acta Biomater. 2018;72:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai L., Zhang J., Qian J., Li Q., Li H., Yan Y.G., Wei S.C., Wei J., Su J.C. The effects of surface bioactivity and sustained-release of genistein from a mesoporous magnesium-calcium-silicate/PK composite stimulating cell responses in vitro, and promoting osteogenesis and enhancing osseointegration in vivo. Biomater Sci-Uk. 2018;6:842–853. doi: 10.1039/c7bm01017f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao C.C., Wang Y., Han F.X., Yuan Z.Q., Li Q., Shi C., Cao W.W., Zhou P.H., Xing X.D., Li B. Antibacterial activity and osseointegration of silver-coated poly(ether ether ketone) prepared using the polydopamine-assisted deposition technique. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:9326–9336. doi: 10.1039/c7tb02436c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma R., Tang T.T. Current strategies to improve the bioactivity of PEEK. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:5426–5445. doi: 10.3390/ijms15045426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan B., Cheng Q.W., Zhao R., Zhu X.D., Yang X., Yang X., Zhang K., Song Y.M., Zhang X.D. Comparison of osteointegration property between PEKK and PEEK: effects of surface structure and chemistry. Biomaterials. 2018;170:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naskar D., Ghosh A.K., Mandal M., Das P., Nandi S.K., Kundu S.C. Dual growth factor loaded nonmulberry silk fibroin/carbon nanofiber composite 3D scaffolds for in vitro and in vivo bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2017;136:67–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai L., Pan Y.K., Tang S.C., Li Q., Tang T.T., Zheng K., Boccaccini A.R., Wei S.C., Wei J., Su J.C. Macro-mesoporous composites containing PEEK and mesoporous diopside as bone implants: characterization, in vitro mineralization, cytocompatibility, and vascularization potential and osteogenesis in vivo. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:8337–8352. doi: 10.1039/c7tb02344h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Converse G.L., Conrad T.L., Roeder R.K. Mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite whisker reinforced polyetherketoneketone composite scaffolds. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2009;2:627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landy B.C., Vangordon S.B., McFetridge P.S., Sikavitsas V.I., Jarman-Smith M. Mechanical and in vitro investigation of a porous PEEK foam for medical device implants. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2013;11:e35–44. doi: 10.5301/JABFM.2012.9771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou J., Lin H., Fang T.L., Li X.L., Dai W.D., Uemura T., Dong J. The repair of large segmental bone defects in the rabbit with vascularized tissue engineered bone. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1171–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu T., Wen J., Qian S., Cao H.L., Ning C.Q., Pan X.X., Jiang X.Q., Liu X.Y., Chu P.K. Enhanced osteointegration on tantalum-implanted polyetheretherketone surface with bone-like elastic modulus. Biomaterials. 2015;51:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller U., Imwinkelried T., Horst M., Sievers M., Graf-Hausner U. Do human osteoblasts grow into open-porous titanium? Eur. Cell. Mater. 2006;11:8–15. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v011a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y., Wong H.M., Wang W.H., Li P.H., Xu Z.S., Chong E.Y.W., Yan C.H., Yeung K.W.K., Chu P.K. Cytocompatibility, osseointegration, and bioactivity of three-dimensional porous and nanostructured network on polyetheretherketone. Biomaterials. 2013;34:9264–9277. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng Y., Liu X.C., Xu A.X., Wang L.X., Luo Z.Y., Zheng Y.F., Deng F., Wei J., Tang Z.H., Wei S.C. Effect of surface roughness on osteogenesis in vitro and osseointegration in vivo of carbon fiber-reinforced polyetheretherketone-nanohydroxyapatite composite. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:1425–1447. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S75557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H.Y., Kwok D.T.K., Xu M., Shi H.G., Wu Z.W., Zhang W., Chu P.K. Tailoring of mesenchymal stem cells behavior on plasma-modified polytetrafluoroethylene. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:3315–3324. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J.P., Li L.L., Fu C., Yang F., Jiao Z.X., Shi X.C., Ito Y., Wang Z.L., Liu Q.Y., Zhang P.B. Micro-porous polyetheretherketone implants decorated with BMP-2 via phosphorylated gelatin coating for enhancing cell adhesion and osteogenic differentiation. Colloids Surf., B. 2018;169:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdullah M.R., Goharian A., Kadir M.R.A., Wahit M.U. Biomechanical and bioactivity concepts of polyetheretherketone composites for use in orthopedic implantsa review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2015;103:3689–3702. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frost H.M. From Wolff's law to the Utah paradigm: insights about bone physiology and its clinical applications. Anat. Rec. 2001;262:398–419. doi: 10.1002/ar.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y.X., Han J.M., Chai Y., Yuan S.P., Lin H., Zhang X.H. Development of porous chitosan/tripolyphosphate scaffolds with tunable uncross-linking primary amine content for bone tissue engineering. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater. 2018;85:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokubo T., Takadama H. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials. 2006;27:2907–2915. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamburaci S., Tihminlioglu F. Biosilica incorporated 3D porous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater. 2018;91:274–291. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z.L., Chen L., Wang Y., Chen X.S., Zhang P.B. Improved cell adhesion and osteogenesis of op-HA/PLGA composite by poly(dopamine)-assisted immobilization of collagen mimetic peptide and osteogenic growth peptide. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2016;8:26559–26569. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b08733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahjoubi H., Buck E., Manimunda P., Farivar R., Chromik R., Murshed M., Cerruti M. Surface phosphonation enhances hydroxyapatite coating adhesion on polyetheretherketone and its osseointegration potential. Acta Biomater. 2017;47:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamburaci S., Tihminlioglu F. Diatomite reinforced chitosan composite membrane as potential scaffold for guided bone regeneration. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater. 2017;80:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menzies K.L., Jones L. The impact of contact angle on the biocompatibility of biomaterials. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2010;87:387–399. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181da863e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cross M.C., Toomey R.G., Gallant N.D. Protein-surface interactions on stimuli-responsive polymeric biomaterials. Biomed. Mater. 2016;11 doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/11/2/022002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y.G., Zhu Y.J., Chen F., Lu B.Q. Dopamine-modified highly porous hydroxyapatite microtube networks with efficient near-infrared photothermal effect, enhanced protein adsorption and mineralization performance. Colloids Surf., B. 2017;159:337–348. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohner M., Lemaitre J. Can bioactivity be tested in vitro with SBF solution? Biomaterials. 2009;30:2175–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouyang L.P., Sun Z.J., Wang D.H., Qiao Y.Q., Zhu H.Q., Ma X.H., Liu X.Y. Smart release of doxorubicin loaded on polyetheretherketone (PEEK) surface with 3D porous structure. Colloids Surf., B. 2018;163:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou J., Guo X.D., Zheng Q.X., Wu Y.C., Cui F.Z., Wu B. Improving osteogenesis of three-dimensional porous scaffold based on mineralized recombinant human-like collagen via mussel-inspired polydopamine and effective immobilization of BMP-2-derived peptide. Colloids Surf., B. 2017;152:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ouyang L.P., Zhao Y.C., Jin G.D., Lu T., Li J.H., Qiao Y.Q., Ning C.Q., Zhang X.L., Chu P.K., Liu X.Y. Influence of sulfur content on bone formation and antibacterial ability of sulfonated PEEK. Biomaterials. 2016;83:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakus A.E., Geisendorfer N.R., Lewis P.L., Shah R.N. 3D-printing porosity: a new approach to creating elevated porosity materials and structures. Acta Biomater. 2018;72:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song J.E., Tripathy N., Lee D.H., Park J.H., Khang G. Quercetin inlaid silk fibroin/hydroxyapatite scaffold promoting enhanced osteogenesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018 doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b08119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haugh M.G., Vaughan T.J., Madl C.M., Raftery R.M., McNamara L.M., O'Brien F.J., Heilshorn S.C. Investigating the interplay between substrate stiffness and ligand chemistry in directing mesenchymal stem cell differentiation within 3D macro-porous substrates. Biomaterials. 2018;171:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen S.C., Guo Y.L., Liu R.H., Wu S.Y., Fang J.H., Huang B.X., Li Z.P., Chen Z.F., Chen Z.T. Tuning surface properties of bone biomaterials to manipulate osteoblastic cell adhesion and the signaling pathways for the enhancement of early osseointegration. Colloids Surf., B. 2018;164:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chappuis V., Maestre L., Burki A., Barre S., Buser D., Zysset P., Bosshardt D. Osseointegration of ultrafine-grained titanium with a hydrophilic nano-patterned surface: an in vivo examination in miniature pigs. Biomater Sci-Uk. 2018;6:2448–2459. doi: 10.1039/c8bm00671g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karageorgiou V., Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474–5491. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan J., Zhou W., Jia Z., Xiong P., Li Y., Wang P., Li Q., Cheng Y., Zheng Y. Endowing polyetheretherketone with synergistic bactericidal effects and improved osteogenic ability. Acta Biomater. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu G.M., Hsiao W.D., Kung S.F. Investigation of hydroxyapatite coated polyether ether ketone composites by gas plasma sprays. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2009;203:2755–2758. [Google Scholar]