Highlights

-

•

Antibiotic therapy and surgical debridement as a form of treatment of actinomycosis.

-

•

Actinomycosis does not respond well antibiotic therapy before curettage.

-

•

Debridement proved to be important for the reduction of antibiotic therapy time.

Keywords: Actinomycosis, Antibiotic prophylaxis, Debridement, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Actinomycosis is a rare chronic disease caused by bacterial infection of the Actinomyces genus. Standard treatment usually involves drainage and high doses of antibiotic therapy, which takes between 6–12 weeks for complete resolution.

Presentation of case

A 57-year-old male was admitted with soft tissue infection-like inflammation of the parasymphysis region, further diagnosed as cervicofacial actinomycosis. Treatment comprised of surgical debridement associated with antibiotic therapy, which took only 4 weeks for complete healing.

Discussion

Although surgical debridement isn’t part of the standard treatment, it has shown to be an interesting tool for promoting quick healing and infection control.

Conclusion

The authors reported a successfully treatment of cervicofacial actinomycosis using surgical debridement as an adjuvant therapy, promoting faster healing, reducing antibiotic therapy time, costs and risks of bacterial resistance, which must be considered as an alternative approach in similar cases.

1. Introduction

Actinomycosis is a rare, non-transmissible, infection caused by anaerobic gram-positive bacteria or microaerophiles, belonging to the genus Actinomyces, which make up the normal flora of the oral cavity [1]. About 50% of actinomycosis cases occur in the cervicofacial region and result mainly from dental infections, while the other half is divided mostly between the abdominal-pelvic and pulmonary regions [2]. In the cervicofacial region, the soft tissues of the submandibular, submental and nasogenian regions are the most commonly involved, with perimandibular involvement being the most frequent clinical presentation [3]. The treatment of actinomycosis can be challenging, given the need for long-term antibiotic therapy, leading patients to incomplete treatment, favouring recurrence [4].

Actinomyces israelii is pointed out as the main cause of this infection, with tonsillium crypts, biofilm and dental calculus, decayed dentin, gingival sulcus and periodontal pockets as its preferred sites of colonisation in healthy individuals [5].

Clinically, actinomycosis is characterized as swelling of soft tissues and formation of microabscess, overtime, these microabscesses can join each other and form painful abscess, causing symptoms such as erythema, oedema and suppuration that when extended to the surface, form a fistulous path and may form multiple fistulas [6].

The differential diagnosis of actinomycosis is generally difficult because it begins slowly and has non-specific symptoms, which can be confused with cellulitis, other common infections of subcutaneous tissue or even neoplasms [7]. An important characteristic that helps in the differential diagnosis is the identification of sulphurous granules in the tissue or exudate of a suspected lesion through biopsy and subsequent histopathological analysis, which can be associated with culture of microorganisms [8].

Since these microorganisms are slow-growing and insidious, the treatment of actinomycosis is not simple and is based on antibiotic therapy, with surgical debridement indicated only in the presence of bone lesions, such as in cases associated with osteomyelitis [9,1]. In cases of soft tissue lesions, regression of infection is achieved with penicillin treatment for 5–6 weeks, when associated with surgical treatment. In patients with deep infections, treatment for up to 12 months may be required if no surgical therapy is performed [3]. Table 1 summarizes cases presented in the literature [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]].

Table 1.

Literature data on treatment of actinomycosis.

| Article Type | Authors/Publication Date | Sex/Age | Affected Tissue Area | Interventions | Antibiotic Therapy Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | Wagner et.al., (2002) | M/61 years | Jaw angle | Drainage - placement of Pen Rose type drain | 3 months |

| CR | Varghese et.al., (2004) | M/38 years | Left Parotid Gland | Incisional biopsy of the nodule with underlying parotid tissue | 3 weeksb |

| CR | Volante et.al., (2005) | M/51 years | Right sub-mandibular | Surgical excision of the mass | 4 weeks |

| CR | Menezes et.al., (2006) | M/77 years | Laryngeal | Hospitalization for antibiotic treatment | 6 months |

| CR | Lancella et.al., (2008) | M/39 years | Cervical Right - Neck | Selective right cervical emptying | 1 month and 16 days |

| M/58 years | Right cervical parotid gland | Parotidectomy | 1 months and 5 days | ||

| CR | Carneiro et.al., (2009) | F/28 years | Cervicofacial | Drainage - placement of pen rose type drain | 4 months |

| CR | Lee et.al., (2011) | M/82 years | Upper lip | Complete removal of the Node | 1 month |

| CR | Kura and Rane, (2011) | M/22 years | Right side of the chin | Skin Biopsy | 5 months and 1 week |

| CR | Shikino et.al., (2014) | F/62 years | Right cheek | Excisional biopsy on the right cheek side | 6 months |

| SC | Valour et.al., (2014) | F/37years | Right maxillary sinus | Right maxillary antrostomy | 5 months |

| CR | Kolm et.al., (2014) | F/86 years | Cervicofacial - cheek | Deep skin biopsy | 3 months |

| CR | Kang et.al., (2015) | F/87 years | Lower lip | Extensive excision of the lesion | 2 weeksa |

| CR | Puri et.al., (2015) | M/22 years | Right submandibular gland | Surgical excision of the right submandibular gland | 4 weeks |

| CR | Cohn et.al., (2017) | F/50 years | Right maxillary sinus | Right functional endoscopic surgery, maxillary antrostomy and anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy. | 2 months |

| SC | Bortoluzzi, et.al., (2020) | 10 F and M/25–68 years | Cheek, Chin and Right latero-cervical region | Surgical drainage and debridement of the oral cavity | 16–24 weeks |

List of abbreviations: CR, case report; SC, series of cases; M, male; F, female.

High dosage of antibiotics: 6G of Amocyxillin.

Patient presented scars with deformity and asymmetry of the face.

The need for prolonged antibiotic therapy can be a major disadvantage in standard actinomycosis therapy, especially in underdeveloped countries where the costs of this treatment is associated with difficulties for continuous evaluation and monitoring, leading to the recurrence of the lesion and increased microbial resistance. Based on issues discussed above, this study aimed to report a case of actinomycosis in the perimandibular region treated with antibiotic therapy in combination with surgical debridement. This combined treatment showed a faster resolution of the infection, which reduced the time and costs of treatment, minimising the potentially negative effects of prolonged antibiotic therapy.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [21].

2. Presentation of case

A 57-year-old male was admitted with a swollen region of 4 cm in diameter on the right parasymphyseal region, mild local pain, no fever or other systemic symptoms (Fig. 1A). The patient reported that the lesion appeared 30 days before as a result of nail-scratching an itching area and it was treated at that time with one-week of antibiotics (sulfas and tetracyclines).

Fig. 1.

Clinical aspects—Initial aspect of the infectious process (A); Erythematous lesion with the presence of granules (B); Lesion after surgical debridement (C); Initial healing 4 days after the primary intervention (D).

Facial examination, it was possible to observe the presence of a diffuse erythematous lesion with several clustered fistulas. The soft tissues in this region were tender and the presence of yellowish granules with different dimensions were noticed (Fig. 1B).

Upon oral examination, no periapical or bone lesions were observed on panoramic X-ray. Severe periodontal disease was found, but it was not related to the current cervicofacial infection (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Panoramic radiography: teeth with severe periodontal disease—31.41 and 42—but without the presence of bone rarefaction.

Combined surgical and antibiotic treatment was selected, in which surgical debridement was performed for helping drainage and for removing necrotic tissues. A biopsy sample was taken for histological evaluation (Fig. 1C). Antibiotic therapy consisted of administering 500 mg of amoxicillin 3 times a day for 30 days.

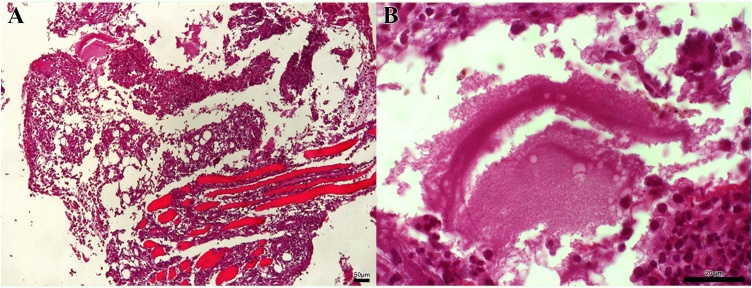

The histopathological examination was carried out using haematoxylin and eosin staining. It showed a chronic inflammatory infiltrate with granuloma formation surrounding collections of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and colonies of microorganisms (Fig. 3). The actinomyces colonies had formed a discrete pattern of radiated rosettes, and areas of haemorrhage were also present, suggesting the diagnosis of actinomycosis.

Fig. 3.

Images of histological examination at 10x (A and C) and 63x (B and D).

The swollen was gradually reduced and healing of fistulas stated quickly after the surgical debridement. The patient was followed-up periodically and a very favourable healing began to occur on the fourth postoperative day, with no more purulent drainage (Fig. 1D). On the 12th postoperative day, an area of fibrosis could already be seen promoting wound closure in regions where the fistulas were previously located (Fig. 4). Over a period of 4 weeks, the patient finished the antibiotic treatment, and the inflamed-infectious process healed, along with complete healing of the skin. (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Clinical aspect 12 days after surgery.

Fig. 5.

Final clinical appearance after 4 weeks.

3. Discussion

Actinomycosis is an infection of bacterial origin, which treatment has proven quite challenging according to the few studies conducted on cervicofacial soft tissue actinomycosis. The techniques applied today are still the same as 20 years before, which include extended courses of antibiotics and, sometimes, drainage of abscess. Surgical debridement, besides of draining abscesses, allows removal of necrotic tissues, helping immune cells of doing this task and letting them to focus on bacterial killing and tissue healing. After debridement, the local blood flow is improved, which also helps the entire healing process. However, just a few authors have used this technique that showed excellent results in treating our case [22,23].

Long-term antibiotic therapy is common for treating routine cases of actinomycosis as shown in Table 1. Most reports focus only in abscess drainage or tissue biopsy, somehow neglecting the advantages of surgical debridement on tissue healing. Usually, conservative management is linked to prolonged antibiotic therapy [7,9,12,15].

In this report, we present an uncommon case of actinomycosis in the parasymphysis region treated surgically with debridement and a short course of antibiotics (4 weeks). The reduction of antibiotic therapy was possible due to the use of surgical debridement, which consists of the removal of non-viable tissue, cellular debris, exudate and all foreign residues of the lesion. The technique is less invasive compared to a complete surgical excision of the lesion; thus, the healing period is shorter and scar area becomes smaller.

In 1997, Nagler et al. [24] raised the hypothesis that patients with actinomycosis do not respond well to antibiotic therapy before degranulation and curettage or resection of the region. It was attributed to compartmentalization of microorganisms (Sulphur granules) within the granulation tissue, making it difficult to antibiotics reaching the infection site due to limited blood supply [24]. However, this study was carried out in a series of patients who had intraosseous infections, and the efficiency of the technique in soft tissue lesions was not tested.

It is worth mentioning that the use of high doses of antibiotics for a long period of time can have side effects, such as renal insufficiency or kidney stones, tooth pigmentation, liver, brain and eye damage, among others, besides promoting bacterial resistance. The cost of treatment is also higher, considering the cost of prolonged antibiotics.

4. Conclusion

Surgical debridement appeared to be a valuable technique to treat a rare case of cervicofacial actinomycosis. Surgical debridement improves infection control, tissue healing and reduces antibiotic therapy. This seems to be one of the few papers to mention the use of this simple surgical technique to treat cervicofacial actinomycosis. Based on these findings, we suggest that surgical debridement can be an alternative measure that have beneficial effects and must be considered in all cases of cervicofacial actinomycosis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest in formulating this article.

Sources of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

We declare that our institution does not require ethical approval of clinical case reports.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

JJVP and ALRR contributed in conceptualisation, KMB contributed in study concept and design, JJVP and KMB contributed in writing the paper.

Registration of research studies

None.

Guarantor

The guarantor of this work, Joao de Jesus Viana Pinheiro, accept full responsibility for the study and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Contributor Information

Karolyny Martins Balbinot, Email: karolbalbinot@gmail.com.

Naama Waléria Alves Sousa, Email: naama_waleria@hotmail.com.

João de Jesus Viana Pinheiro, Email: joaopinheiro@ufpa.br.

André Luís Ribeiro Ribeiro, Email: andre.ribeiro.13@ucl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Valour F., Sénéchal A., Ferry T. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect. Drug Resist. 2014;7:183–197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S.R., Jung L.Y., Oh I.J. Pulmonary actinomycosis during the first decade of 21st century: cases of 94 patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013;13:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaves A., Madeira C., Carvalho S. Chronic mandibular actinomycosis: Anesthetic and infectious implications: about a clinical case. Portuguese Soc. Anesthesiol. 2010;9:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah K.M., Karagir A., Kanitkar S., Koppikar R. An atypical form of cervicofacial actinomycosis treated with short but intensive antibiotic regimen. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bubbico L., Caratozzolo M., Nardi F., Ruoppolo G., Greco A., Venditti M. Actinomycosis of submandibular gland: an unusual presentation. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2004;24:37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moghimi M., Salentijn E., Debets-Ossenkop Y., Karagozoglu K.H., Forouzanfar T. Treatment of cervicofacial actinomycosis: a report of 19 cases and review of literature. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2013;18:e627–e632. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carneiro G., Barros A.C., Fracassi L.D., Sarmento V.A., Farias J.G. Actinomycese cervicofacial: clinical case report. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Traumatol. 2010;10:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraz A.C., Melo C.V.M., Pereira E.L.R., Stávale J.N., Nogueira R.G., Gabbai A.A., Malheiros S.M.F., Prandini M.N. Actinomycosis of the central nervous system: a rare complication of actinomycose cervicofacial. Arch. Neuro-Psychiatry. 1993;51:358–362. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1993000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner J.B., Gomes J.P., Volkweis M.R. Imaging exams as auxiliary to diagnosis of cervicofacial actinomycosis. Rev. Cir. Traumat. Buccomaxillofac. 2002;2:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varghese B.T., Sebastian P., Ramachandran K., Pandey M. Actinomycosis of the parotid masquerading as malignant neoplasm. BMC Câncer. 2004;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volante M., Contucci A.M., Fantoni M., Ricci R., Galli J. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: still a difficult differential diagnosis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2005;25(2):116–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menezes M.C., Tornin O., de S., Botelho R.A., de Brito J.P., Júnior, Ortellado D.K., Torres L.R. Laryngeal actinomycosis: case report. Braz. Radiol. 2006;39(4):309–311. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lancella A., Abbate G., Foscolo A.M., Dosdegani R. Two unusual presentations of cervicofacial actinomycosis and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2008;28(2):89–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y.S., Sim H.S., Lee S.K. Actinomycosis of the upper lip. Ann. Dermatol. 2011;13(23 Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.5021/ad.2011.23.S1.S131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kura M.M., Rane V.K. Cervicofacial actinomycosis mimicking lymphangioma circumscriptum. Indian J. Dermatol. 2011;56:321–323. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.82493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shikino K., Ikusaka M., Takada T. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014;30(2):263. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3001-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolm I., Aceto L., Hombach M., Kamarshev J., Hafner J., Urosevic-Maiwald M. Actinomycesecervicofacial: a long-standing infectious complication of immunosuppression - case report and literature review. Dermatol. Online J. 2014;20(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang J.S., Choi H.J., Tak M.S. Actinomycosis and Sialolithiasis in the submandibular gland. Arch. Craniofacial Surg. 2015;16(1):39–42. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2015.16.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puri H., Narang V., Chawla J. Actinomycosis of submandibular gland: an unusual presentation of a rare entity. J. Oral Maxillofacialpathol.: JOMFP. 2015;19(1):106. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.157212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohn J.E., Lentner M., Li H., Nagorsky M. Unilateral maxillary sinus actinomycosis with a closed oroantral fistula. Case Rep. Otolaryngol. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/7568390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Updating Consensus Surgical Case Report (SCARE) Guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bortoluzzi P., Nazzaro G., Giacalone S. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: a report of 14 patients observed at the Dermatology Unit of the University of Milan, Italy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ijd.14934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glass G.E., Staruch R.M.T., Bradshaw K. Pediatric cervicofacial actinomycosis: lessons from a craniofacial unit. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019;30:2432–2438. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagler R., Peled M., Laufer D. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 1997;83:652–656. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]