Abstract

Background

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is characterized by elevated pulmonary arterial pressures and is managed by vasodilator therapies. Current guidelines encourage PAH management in specialty care centers (SCCs), but evidence is sparse regarding improvement in clinical outcomes and correlation to vasodilator use with referral.

Research Question

Is PAH management at SCCs associated with improved clinical outcomes?

Study Designand Methods

A single-center, retrospective study was performed at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC; overseeing 40 hospitals). Patients with PAH were identified between 2008 and 2018 and classified into an SCC or non-SCC cohort. Cox proportional hazard modeling was done to compare for all-cause mortality, as was negative binomial regression modeling for hospitalizations. Vasodilator therapy was included to adjust outcomes.

Results

Of 580 patients with PAH at UPMC, 455 (78%) were treated at the SCC, comprising a younger (58.8 vs 64.8 years; P < .001) and more often female (68.4% vs 51.2%; P < .001) population with more comorbidities without differences in race or income. SCC patients demonstrated improved survival (hazard ratio, 0.68; P = .012) and fewer hospitalizations (incidence ratio, 0.54; P < .001), and provided more frequent disease monitoring. Early patient referral to SCC (< 6 months from time of diagnosis) was associated with improved outcomes compared with non-SCC patients. SCC patients were more frequently prescribed vasodilators (P < .001) and carried more diagnostic PAH coding (P < .001). Vasodilators were associated with improved outcomes irrespective of location but without statistical significance when comparing between locations (P > .05).

Interpretation

The UPMC SCC demonstrated improved outcomes in mortality and hospitalizations. The SCC benefit was multifactorial, with more frequent vasodilator therapy and disease monitoring. These findings provide robust evidence for early and regular referral of patients with PAH to SCCs.

Key Words: compliance, pulmonary arterial hypertension, quality of care, specialty care center, vasodilator

Abbreviations: 6MWT, 6-minute walk test; EHR, electronic health record; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonist; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; IR, incidence ratio; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PDE5i, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PR, prostacyclin derivatives and analogs; RHC, right-sided heart catheterization; SCC, specialty care center; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; UPMC, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; WSPH, World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 28

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare disease characterized by elevation of pulmonary arterial pressures that can progress to right ventricular failure and death.1, 2, 3 In the past, use of pulmonary vasodilators has correlated with improved 5-year survival, most recently reported at 57% in the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Disease Management (REVEAL Registry).3, 4, 5, 6 Combination therapy with vasodilator classes is also associated with improved outcomes including functional status, disease progression, hemodynamic markers, and hospitalizations.7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Despite these advances, missed opportunities to improve PAH outcomes may be related to delayed diagnosis, misdiagnosis, and late or inappropriate implementation of treatment.12, 13, 14, 15 As a result, time to diagnosis is prolonged, often years from symptom onset and after evaluation by multiple physicians. This results in diagnosis at more advanced stages of disease correlating with worsened patient outcomes.3,12,13,16,17

The PAH management schema are rapidly evolving and show variable rates of compliance.5 Given the disease complexity, educational efforts have increased within the medical community for referral to specialty care centers (SCCs) for management.18, 19, 20, 21 Within the United States, the Pulmonary Hypertension Association developed the Pulmonary Hypertension Care Center initiative to operationalize this recommendation and has granted accreditation to qualifying SCCs such as University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Presbyterian Hospital providers.22 Outside this SCC, UPMC manages providers at an additional 39 separate regional hospitals with a centralized, searchable electronic health record (EHR) allowing direct comparison of outcomes from specialty and nonspecialty PAH care in the same geographical area. However, incomplete evidence exists regarding whether the implementation of SCCs positively impacts patient care. In this study, we investigated whether PAH management at SCCs is associated with improved patient outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

The Institutional Review Board at UPMC approved the study (IRB number: PRO11070366), and all subjects provided written informed consent (a general research consent for all patients seen at UPMC facilities). A database of patients with PAH was constructed via the Medical Archival Retrieval System, a repository of UPMC health data.23,24 Patients were identified by having at least one right-sided heart catheterization (RHC) performed between January 1, 2008 and December 3, 2018 with hemodynamics indicative of precapillary disease outlined by the 2013 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) hemodynamic criteria for PAH: mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) ≥ 25 mm Hg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ≤ 15 mm Hg, and pulmonary vascular resistance > 3 Wood units.25,26 The 2019 criteria27 with a less stringent mPAP cutoff were not used, as these were not relevant for referral prior to 2019. After hemodynamic identification, third-party expert clinicians reviewed clinical notes and relevant studies for a determination of WSPH classification. Notably, a group 1 PAH diagnosis was made only after excluding patients with confounding variables from etiologies more consistent with left-sided heart disease and hypoxic lung disease. Patients with PAH were stratified into two cohorts, using clinic encounter information. Patients who had at least one encounter with an established provider of the UPMC SCC were included in the SCC cohort and compared with those treated outside this specialty care center (non-SCC). In the UPMC PAH practice model, SCC providers routinely conduct patient care at non-SCC locations. Thus, randomization was made to SCC providers, not hospitals.

Data Collection

Baseline demographic and clinical data including comorbidities and laboratory values were cataloged, including transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) results, and hemodynamic data from RHC. These characteristics were collected independent of cohort designation and based on closest clinical data to t0. For longitudinal comparisons, t0 was set as either the first RHC meeting precapillary hemodynamic criteria of PAH or the first instance of primary diagnosis of PAH by International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) or ICD-10 code, whichever occurred first. Cardiac output (CO) was taken from the index RHC or within 6 months of t0. CO determined by indirect Fick procedure (Fick CO) was preferentially selected because of better coverage, and thermal CO was used in the absence of Fick CO.

For socioeconomic status, ZIP codes were used in conjunction with government census data28 to determine median income and distance from center. Medications were cataloged through manual curation. Use frequency of guideline-directed disease-monitoring tools21 was recorded including RHC, pulmonary function testing, and TTE. Because the UPMC EHR system reports functional exercise testing via various fields, manual curation of PAH-specific functional assessments was performed, including 6-min walk testing (6MWT) and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Clinical outcomes, including all-cause hospitalizations at UPMC facilities and mortality, were determined by EHR search and cross-referenced with the Social Security Death Index, respectively. e-Appendix 1 contains additional information on data collection.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile range whereas categorical variables are reported as percentages. Cox proportional hazard modeling was used for mortality, presented as crude and adjusted (after including clinically important confounders) hazard ratios (HRs). Negative binomial regression (with length of follow-up as offset variable) was used to compare hospital admissions since t0 between locations, as crude and adjusted incidence ratio (IR). The final confounders in multivariate models were selected using the Akaike information criterion.29 A model with all clinically important covariates was also analyzed, with consistent results demonstrated across both models (e-Tables 1 and 2).30 Two-sided statistical tests with a P value < .05 were defined as being significant. Test of proportionality of hazard was performed in Cox regression models. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata 15.0 software (StataCorp) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 580 patients in the UPMC system met the WSPH hemodynamic and clinical criteria for PAH. Of these, 455 were managed at the SCC. Table 1 lists the baseline patient characteristics. SCC patients were younger (median age, 58.8 vs 64.8 years; P < .001) and more likely to be female (68.4% vs 51.2%; P < .001). Both cohorts displayed a similar racial and economic profile, carrying a small minority of black patients and comparable median incomes by ZIP code.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics for Specialty Care Center vs Non-Specialty Care Center Cohortsa

| Category | SCC |

Non-SCC |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Results | No. | Results | ||

| Age, y | 455 | 58.8 (49.7-67.4) | 125 | 64.8 (53.8-75.4) | < .001 |

| Sex (female), No. (%) | 455 | 311 (68.4) | 125 | 64 (51.2) | < .001 |

| Maximum distance from SCC, mi | 455 | 43.5 (15.1-89.6) | 125 | 39.5 (9.00-96.3) | .650 |

| Black, No. (%) | 437 | 60 (13.7) | 116 | 21 (18.1) | .239 |

| Income, dollars | 349 | 94 | .383 | ||

| < 40,000/y | 59 (16.9) | 18 (19.2) | |||

| 40,000-50,000/y | 107 (30.7) | 27 (28.7) | |||

| 50,000-65,000/y | 103 (29.5) | 34 (36.2) | |||

| > 65,000/y | 80 (22.9) | 15 (16.0) | |||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Smoking, No. (%) | 455 | 220 (48.4) | 125 | 49 (39.2) | .069 |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 455 | 225 (49.5) | 125 | 49 (39.2) | .042 |

| Atrial fibrillation, No. (%) | 455 | 51 (11.2) | 125 | 10 (8.0) | .300 |

| CHF, No. (%) | 455 | 265 (58.2) | 125 | 76 (60.8) | .607 |

| CAD/CABG, No. (%) | 455 | 72 (15.8) | 125 | 26 (20.8) | .189 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 455 | 49 (10.8) | 125 | 17 (13.6) | .377 |

| Hyperlipidemia, No. (%) | 455 | 74 (16.3) | 125 | 20 (16.0) | .944 |

| Obesity, No. (%) | 455 | 239 (52.5) | 125 | 49 (39.2) | .008 |

| COPD, No. (%) | 455 | 149 (32.8) | 125 | 44 (35.2) | .606 |

| OSA, No. (%) | 455 | 81 (17.8) | 125 | 10 (8.0) | .008 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis, No. (%) | 455 | 178 (39.1) | 125 | 42 (33.6) | .260 |

| ESRD, No. (%) | 455 | 35 (7.7) | 125 | 5 (4.0) | .149 |

| Cirrhosis, No. (%) | 455 | 58 (12.8) | 125 | 14 (11.2) | .642 |

| DVT/PE, No. (%) | 455 | 18 (4.0) | 125 | 7 (5.6) | .423 |

| Laboratory values | |||||

| BMI | 377 | 27.3 (27.3-31.5) | 86 | 28.8 (24.4-33.8) | .220 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide | 222 | 334 (129-794) | 66 | 467 (198-1035) | .093 |

| Creatinine | 381 | 0.9 (0.8-1.2) | 80 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | .420 |

| Invasive hemodynamics | |||||

| mPAP, No. (%) | 455 | 387 (85.1) | 125 | 112 (89.6) | .19 |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 387 | 45.0 (36.0-53.0) | 112 | 40.5 (32.0-47.0) | < .001 |

| sPAP, mm Hg | 385 | 73.0 (58.5-85.5) | 108 | 64.5 (50.0-76.5) | < .001 |

| dPAP, mm Hg | 381 | 26.0 (20.0-34.0) | 106 | 23.5 (19.0-30.0) | < .001 |

| PAWP, mm Hg | 382 | 10.0 (8.0-13.0) | 107 | 10.0 (8.0-13.0) | .410 |

| sRVP, mm Hg | 372 | 73.0 (58.5-85.5) | 102 | 65.5 (51.0-75.0) | < .001 |

| CO (F or TD), L/min | 376 | 4.8 (3.8-5.7) | 115 | 4.9 (3.6-5.8) | .73 |

| TPG, mm Hg | 376 | 33.0 (24.0-42.0) | 105 | 30.0 (23.0-38.0) | .003 |

| PVR (F or TD), Wood units | 353 | 6.9 (4.6-10.0) | 102 | 5.8 (4.3-8.3) | .470 |

CAD/CABG = coronary arterial disease/coronary artery bypass graft; CHF = congestive heart failure; CO (F or TD) = cardiac output determined by indirect Fick or thermodilution; dPAP = diastolic pulmonary arterial pressure; DVT/PE = deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolus; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; mPAP = mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PAWP = pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; PFT = pulmonary function test; PVR (F or TD) = pulmonary vascular resistance with CO determined by indirect Fick or thermodilution; RHC = right-sided heart catheterization; SCC = specialty care center; sPAP = systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; sRVP = systolic right ventricular pressure; TPG = transpulmonary gradient; TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram.

Results are expressed as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise specified.

Among screened comorbidities, hypertension (49.5% vs 39.2%; P = .042), obesity (52.5% vs 39.2%; P = .008), and OSA (17.8% vs 8.0%; P = .008) were more prevalent in the SCC. On average, patients lived a similar distance from their respective centers (43.5 vs 39.5 mi; P = .65). Transthoracic echocardiography characteristics of each cohort were not significantly different (e-Table 3).

By some hemodynamic indexes, SCC patients had more severe PAH with higher mean (mPAP), systolic, and diastolic pulmonary arterial pressure (45.0, 73.0, and 26.0 mm Hg vs 40.5, 64.5, and 23.5 mm Hg, respectively; P < .001), systolic right ventricular pressure (73.0 vs 65.5 mm Hg; P < .001), and transpulmonary gradient (33 vs 30 mm Hg; P < .003). However, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, CO, and pulmonary vascular resistance were not significantly different between cohorts.

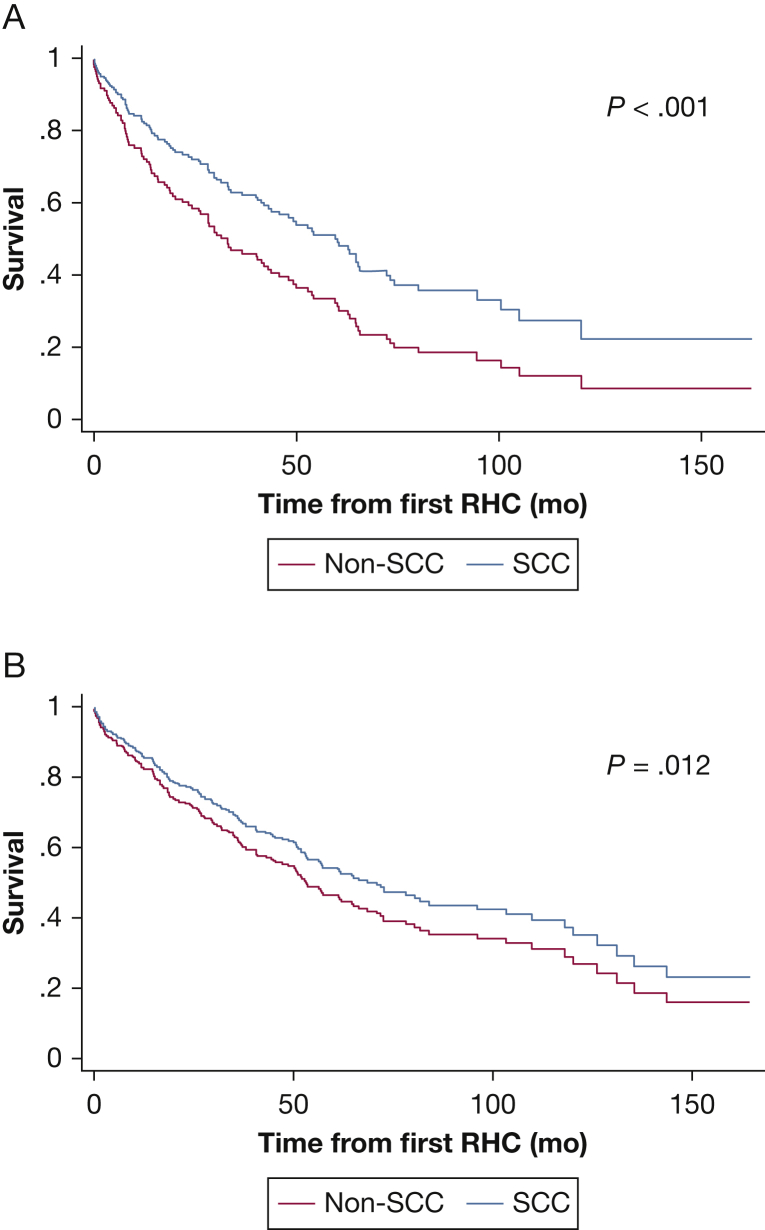

Improved Outcomes in the SCC

SCC patients displayed significantly better survival compared with non-SCC patients (crude HR, 0.53; P < .001; Table 2). When adjusted for age, comorbidities, lung transplant status, and CO as a marker of PAH severity, the significance remained (adjusted HR, 0.68; P = .012, adjusted cumulative survival plots in Fig 1A). To account for a known survivorship bias observed in PAH populations,4,31,32 Figure 1B displays a postestimation plot from Cox analysis that compared survival in patients who were referred to the SCC within 6 months of diagnosis (early referral) vs non-SCC patients. The early referral cohort in SCC still showed significantly better survival than non-SCC patients (P = .043). Moreover, when only examining patient mortality within the first 6 months since diagnosis, the overall survival in SCC patients referred early was still improved (89.6%) vs in non-SCC patients (76.1%; adjusted P = .007). Both sexes displayed improved mortality in the SCC (crude HR, 0.48; P < .001 for male patients; crude HR, 0.61; P = .012 for female patients) (Fig 2). There was no statistically significant difference when testing for the interaction between sex and center type. Overall, the SCC had fewer hospital admissions (IR, 0.55 [P < .001]; adjusted IR, 0.54 [P < .001]) (Table 2), especially for female patients (crude IR, 0.50; P < .001). Male patients did not display a statistically significant hospitalization reduction in the SCC. Furthermore, most of the SCC patients were seen multiple times by the SCC, with only 58 patients (12.7%) reporting only one SCC visit. When these one-visit SCC patients were reclassified into the non-SCC cohort, the positive effects on SCC outcomes remained (HR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.53-0.92], P = .009; IR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.44-0.6], P < .001).

Table 2.

Effects of Specialty Care Centers vs Non-Specialty Care Centers on Mortality and Hospital Admissions, With Specification on Sex Differencesa

| Patients | Crude Outcome | Adjusted Outcomeb |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.53 (0.41-0.69)c | 0.68 (0.50-0.92)d |

| IR (95% CI) | 0.55 (0.45-0.74)c | 0.54 (0.42-0.69)c |

| Male patients | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.48 (0.33-0.72)c | … |

| IR (95% CI) | 0.74 (0.51-1.07) | … |

| Female patients | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.61 (0.42-0.90)d | … |

| IR (95% CI) | 0.50 (0.36-0.69)c | … |

Results for mortality are reported as hazard ratio (HR) and for number of hospitalizations as incidence ratio (IR). P value for interaction between sex and specialty care center was .17 for mortality and .22 for hospital admission. P for proportional hazard = .16.

HR is adjusted for sex, age, cardiac output (CO), lung transplant status, and comorbidities (OSA, obesity, and pulmonary fibrosis). IR is adjusted for sex, age, CO, lung transplant status, and comorbidities (coronary arterial disease/coronary artery bypass graft, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolus, end-stage renal disease, obesity). For the number of hospitalizations model, the length of follow-up was added as an offset variable.

P ≤ .001.

P < .05.

Figure 1.

Specialty care center (SCC) patients displayed improved mortality compared with non-SCC counterparts. A, Adjusted cumulative survival among patients treated at SCCs vs non-SCC patients. B, Postestimation plot from Cox model to compare survival of patients referred early to SCCs (within 6 months of diagnosis) and non-SCC patients. RHC = right-sided heart catheterization.

Figure 2.

A and B, Crude cumulative survival curves for male (A) and female (B) patients treated at SCC vs non-SCC. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

Differences in Vasodilator Use

The frequency of vasodilator usage including four major drug classes is displayed in Table 3: phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors (PDE5i), riociguat (soluble guanylyl cyclase agonists), endothelin receptor antagonists (ERA), and prostacyclin derivatives and analogs (PR). Overall, SCC patients demonstrated substantially more frequent use of vasodilators in all classes (80.7% vs 34.7%; P < .001) and more use of specific PDE5i and ERA combination (30.1% vs 14.0%; P < .001). Riociguat assessment was limited by small sample size. SCC patients had significantly longer duration of PR therapy (e-Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of Frequencya of Vasodilator Use in Specialty Care Centers vs Non-Specialty Care Centers

| Category of Vasodilator | SCC (n = 442) | Non-SCC (n = 121) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor (PDE5i) | 312 (70.6) | 38 (31.4) | < .001 |

| Endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) | 163 (36.9) | 21 (17.4) | < .001 |

| Riociguat | 8 (1.8) | 1 (0.8) | .69 |

| Prostacyclin | 161 (36.4) | 7 (5.8) | < .001 |

| Monotherapy (PDE5i or ERA or riociguat) | 336 (76.0) | 41 (33.9) | < .001 |

| PDE5i and ERA combination | 133 (30.1) | 17 (14.0) | < .001 |

| Triple therapy | 66 (14.9) | 7 (5.8) | .008 |

| Any vasodilator | 357 (80.7) | 42 (34.7) | < .001 |

See Table 1 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Expressed as No. (%).

Effects of vasodilator treatment on clinical outcomes are shown in Table 4. Notably, the use of any vasodilator in the SCC was associated significantly with mortality benefit (HR, 0.66; P = .022). There was no statistically significant difference in mortality and hospitalization for non-SCC patients. PDE5i and ERA combination therapy did not demonstrate a statistically significant effect on mortality or hospitalization in SCC patients, but improved mortality significantly in non-SCC patients (HR, 0.31; P = .031). Importantly, despite the substantial differences in mortality and hospitalization between the two cohorts (Table 2), the improvements in these outcomes with vasodilator use were not significantly different when comparing location (P > .05 for interaction between vasodilator use and center type; Table 4). These data emphasize the importance of vasodilator use in improving outcomes across both cohorts. However, vasodilator use alone did not explain the entirety of benefits observed in SCC patients—including the use of PR, which has previously been linked to improved outcomes in patients with PAH in general.33 That is, even with additional adjustment for PR on top of other covariates in Table 2, the SCC patients remained associated with improved mortality (HR, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.52-0.97]; P = .033) and fewer hospital admissions (IR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.45-0.76]; P < .001). This supports the importance of other factors, such as more frequent disease monitoring, to drive additional outcome improvements in SCC patients.

Table 4.

Effects of Vasodilator Treatments on Mortality and Hospital Admissiona

| Vasodilator | SCC | Non-SCC | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy | |||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.70 (0.50-0.98)c | 0.67 (0.38-1.19) | .76 |

| IR (95% CI) | 0.78 (0.60-1.02) | 0.71 (0.47-1.08) | .67 |

| PDE5i and ERA combination | |||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.74 (0.52-1.04) | 0.31 (0.11-0.90)c | .08 |

| IR (95% CI) | 0.91 (0.73-1.15) | 0.84 (0.50-1.39) | .93 |

| Triple therapy | |||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.60 (0.37-0.98)c | 0.36 (0.08-1.52) | .50 |

| IR (95% CI) | 0.62 (0.45-0.84)c | 0.53 (0.26-1.10) | .63 |

| Any vasodilator | |||

| HR (95% CI) | 0.66 (0.46-0.94)c | 0.63 (0.35-1.12) | .73 |

| IR (95% CI) | 0.77 (0.57-1.04) | 0.71 (0.47-1.08) | .61 |

Hazard ratio (HR) is adjusted for sex, age, cardiac output (CO), lung transplant status, and comorbidities (OSA, obesity, and pulmonary fibrosis). Incidence ratio (IR) is adjusted for sex, age, CO, lung transplant status, and comorbidities (coronary arterial disease/coronary artery bypass graft, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolus, end-stage renal disease, obesity). For the number of hospitalizations model, the length of follow-up was added as an offset variable. See Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

Mortality is calculated as an HR; hospitalization as an IR. Reference is made on the basis of no treatment.

Interaction between treatment and type of center.

P < .05.

Differences in Diagnosis and Management

Differences in PAH diagnosis and management between the cohorts are cataloged in Table 5. Diagnostically, SCC patients more frequently carried PAH ICD diagnoses (75.2% vs 30.4%; P < .001). For those patients without ICD codes, significantly more SCC patients were prescribed vasodilator therapy compared with non-SCC patients (80.5% vs 51.7%; P < .001). The number of patients undergoing lung transplantation was not statistically different between cohorts. Overall, functional testing including 6MWT and cardiopulmonary exercise testing were significantly higher in the SCC (71.4% vs 35.2%; P ≤ .001), along with TTEs (83.5% vs 75.2%; P = .033). Notably, invasive RHC was repeated across large majorities in both groups, with a slightly higher rate in non-SCC patients (87.0% vs 93.6%; P = .042); there was no significant difference in repeat RHC per patient. There was significantly more frequent testing in the SCC of pulmonary function (1.4 vs 0.3; P = .024) and TTE (1.9 vs 0.4; P = .004) per patient.

Table 5.

Diagnosis and Management Differences in Specialty Care Centers vs Non-Specialty Care Centers

| Category | SCC |

Non-SCC |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Results | No. | Results | ||

| ICD coding of PAH, No. (%) | 455 | 342 (75.2) | 125 | 38 (30.4) | < .001 |

| Vasodilator use without ICD diagnosis, No. (%) | 113 | 91 (80.5) | 87 | 45 (51.7) | < .001 |

| Lung transplant, No. (%) | 455 | 60 (13.2) | 125 | 9 (7.2) | .067 |

| Disease-monitoring tool testing | |||||

| Functional testing, No. (%) | 455 | 325 (71.4) | 125 | 44 (35.2) | < .001 |

| 6MWT, median (IQR) | 203 | 238 (165-336) | 35 | 216 (91-292) | .110 |

| TTE, No. (%) | 455 | 380 (83.5) | 125 | 94 (75.2) | .033 |

| PFT, No. (%) | 455 | 135 (29.7) | 125 | 38 (30.4) | .880 |

| RHC, No. (%) | 455 | 396 (87.0) | 125 | 117 (93.6) | .042 |

| Repeat disease-monitoring tool testing per patient | |||||

| TTE, mean (SD) | 380 | 1.9 (3.6) | 94 | 0.4 (1.7) | .004 |

| PFT, mean (SD) | 135 | 1.4 (4.2) | 38 | 0.3 (1.5) | .024 |

| RHC, mean (SD) | 396 | 3 (1-6) | 117 | 1 (1-2) | .24 |

6MWT = 6-minute walk test; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; IQR = interquartile range; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Discussion

Despite the expert opinion for referral of patients with PAH to SCCs,15,20,21,25 evidence is incomplete to support that this recommendation would lead to improved patient outcomes. To address this deficiency, this retrospective, single-center analysis highlights crucial differences in care provided at an SCC and offers quantitative proof of the associated improvements of mortality and hospitalization. Even when adjusting for sex, age, CO, and vasodilator use, benefits of SCC referral remained, indicating the overall improved clinical outcomes are multifactorial and go beyond vasodilators alone. Moreover, early SCC referral was associated with improved outcomes, thus strengthening the argument that PAH survivorship bias4,31,32 does not primarily explain these benefits.

Management Differences in SCCs

Our findings emphasized that vasodilator use was associated with outcome improvements across both cohorts. The SCC demonstrated substantially more frequent use of all vasodilator classes consistent with randomized trial data, emphasizing that targeted vasodilator therapy with aggressive combination therapy when appropriate is crucial in PAH management.7, 8, 9, 10, 11,34 Given that the AMBITION (Ambrisentan and Tadalafil Combination Therapy in Subjects With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension) trial was published in 20157 and our data collection began in 2008, our study captured many patients receiving monotherapy before that transition (Table 3). Parenteral prostaglandin therapy is the “gold standard” of treatment for advanced PAH21,25,33 and is used more commonly in referral centers compared with nonspecialty practices.35 Our study confirms similar results, showing that the SCC demonstrated more frequent use of all vasodilators, including PR therapies (Table 3), and for longer duration (e-Table 4). Given the expansion in vasodilator options14,22 combined with the need for administrative approval and availability of support staff trained specifically for PAH care,22,36, 37, 38 SCCs provide a particularly appealing infrastructure for the timely, safe, and appropriate initiation of vasodilator therapy.

In that context, efforts from the Pulmonary Hypertension Association to accredit SCCs and the pharmaceutical industry37 have aimed to increase diagnostic awareness of pulmonary hypertension (PH) within the medical community and encourage patient referrals to improve timely initiation of targeted therapies.36 Despite the unbalanced size of SCC vs non-SCC cohorts in this study, our study emphasizes the need for soliciting appropriate referrals from the community. Namely, in non-SCC patients, the lower frequency of vasodilator use and ICD coding suggested a suboptimal rate of diagnostic recognition of PAH. Alternatively, referral rates may have been affected by the higher prevalence of comorbidities; patients with more complicated and severe disease may have been preferentially referred, whereas patients with less severe PAH may have remained at non-SCCs. Ultimately, these findings enforce a need for improvement in physician diagnostic awareness, initiation of appropriate medical therapy, and dissemination and education to encourage more robust SCC referral after meeting hemodynamic criteria for PAH.

Our study also highlights the contemporary importance of lung transplantation in SCC care. Lung transplantation, while decreasing in frequency because of the expansion of vasodilator therapy, remains a viable surgical remedy in cases of severe, refractory disease.39,40 Yet, only a minority of the patients in our study underwent lung transplantation (Table 5), and therefore this was not the predominant reason for the SCC benefit (Table 2).

In addition, our findings emphasize differences in management strategies involving diagnostic testing and monitoring of disease progression. Specifically, the SCC pursued noninvasive testing more frequently, including exercise testing and TTE (Table 5), following current guidelines for serial functional assessment of disease burden17,41,42 as a way to guide appropriate medication adjustments.41,43 Furthermore, although our data were not granular enough to discern accurately the rate of outpatient testing for OSA, it is notable that significantly more patients with OSA were observed in the SCC, potentially suggesting an increased screening awareness on the part of the SCC, given the predisposition of patients with OSA to PH.44 In both cohorts, invasive testing by RHC was completed at high frequency. The use of this invasive test may have introduced a source of inclusion bias for providers who are comfortable performing and interpreting this test. Yet, given the higher rate of noninvasive surveillance disease monitoring found in the SCC cohort, invasive hemodynamic evaluation alone is unlikely to explain the SCC benefit, but rather suggests that combined, serial invasive and noninvasive surveillance testing contributes to the benefit contained in SCC care. Overall, our study was not structured to determine whether improved adherence to specific algorithms was causatively linked to the improvement in outcomes; future examination of this correlation is warranted in larger cohorts. In “real world” clinical practice, it is also possible that providers, outside of this study, continue to prescribe vasodilator medications inappropriately without invasive hemodynamic evaluation.

Although geographic distance from the location of care, race, and income level were not grossly different between cohorts (Table 1) and thus were not the primary drivers of our results, socioeconomic determinants that affect PAH outcomes45 still could have contributed to the SCC benefit. A more in-depth study is warranted to define socioeconomic and other parameters that influence SCC referral and care, including the availability of ancillary services, recognition of specific disease indexes (ie, right ventricular dysfunction), and management of vasodilators that contribute to drug choice, duration, and interruptions.

Clinical Implications

Our findings offer quantitative support that bolsters efforts to increase PAH referral to SCCs. Encouragingly, rates of referral to SCCs are increasing because of improved awareness and physician education,37 growth of available vasodilator medications and corresponding drug marketing,46 and increased use of noninvasive screening tools.47,48 An increased rate of referral may be associated with the changing PAH demographics, with increasing incidence49 and median age of diagnosis.46 Importantly, our findings should not undermine the crucial role that practitioners outside of SCCs play in providing optimal care, particularly for diagnostic recognition and local longitudinal follow-up, which has been endorsed by the UPMC SCC as standard of care. Future studies should be structured to assess methods for optimizing an interdigitated care system, particularly to prioritize early referral and frequent disease monitoring across other control groups. In that vein, it is possible that results highlighting the benefits of SCC referral may become even more robust, particularly if comparing with a control group without any affiliation to an SCC.

Furthermore, although PAH is the focus of care at SCCs, 3-year survival rates in other WSPH groups of PH are similar without correspondingly increased attention and without targeted therapy.50 Group 2 and 3 PH are more prevalent3 and further studies are needed to determine whether SCC referral would be beneficial.51,52 In addition, group 4 PH, an underdiagnosed subtype,53 carries curative surgical options as well as emerging targeted medical therapy that likely benefits from SCC referral or a dedicated chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension program.54

Study Limitations

There are several limitations in the study. First, this is a single-hospital system where patients within the non-SCC cohort may have received treatment at an SCC outside our system that was not reflected in their clinic documentation. Second, a referral bias may be present, as patients who were more likely to benefit and tolerate vasodilator therapies potentially were more often referred to the SCC. Third, although our multivariate analysis was adjusted ono the basis of CO, which has been validated to correlate with disease severity,17 we were unable to calculate the REVEAL or French Registry risk in our cohorts, due to inconsistent reporting of New York Heart Association/World Health Organization functional class, 6MWT distance, and hemodynamic parameters, particularly in the non-SCC cohort.17,55, 56, 57, 58 In addition, because of inconsistent reporting of CO measurements across hospitals, we supplemented Fick CO with thermodilution CO when Fick CO was not available, which could lead to differences in results. Overall, Fick CO was reported for 90% of patients with CO data, thus allowing for substantial consistency for a majority of patients analyzed. In addition, of patients with both measurements, there was significant correlation between Fick and thermodilution COs. Fourth, ICD codes were used for comorbidity assessment, but reliance on such coding can be confounded by provider misdiagnosis.14,59 To mitigate this error, our study used more stringent objective hemodynamic criteria accompanied by third-party clinician chart review to ensure accuracy in a primary diagnosis of PAH, thereby limiting our sample size. Fifth, although a confounding survivorship bias cannot be entirely discounted in this study, the findings regarding early referrals and mortality strengthen the argument that survivorship bias does not primarily explain the benefits seen in the SCC cohort vs the non-SCC cohort. Finally, challenges existed to determine accurately the index visit for certain non-SCC patients, where erroneous prescription of vasodilators may occur prior to RHC confirmation of PAH.14

Conclusion

Our data indicate that PAH care at an SCC was associated with improvements in all-cause mortality and hospitalization. Although some of SCC benefits are likely derived from increased vasodilator use, differences in management strategies with increased guideline compliance may also contribute. These findings provide crucial support for more robust referral to SCCs and collaboration with the community. Future studies should be pursued to explore further the exact contribution of SCC management processes in modulating PAH outcome.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: S. Y. C. is the guarantor of this project, had full access to the data in the study, and takes responsibility of the content of the manuscript including the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. S. Y. C., H. P., and C. M. K. conceived the main content and the design of the experiment. A. H. performed the computational analyses. H. P. and C. M. K. performed the manual diagnosis of all WSPH classes and recording of functional testing. H. P., C. M. K., M. T., J. V., and G. V. recorded the yearly medications for each patient. M. N. performed the statistical analysis. H. P., C. M. K., and S. Y. C. wrote the manuscript. M. N., M. A. S., M. G. R., A. D., M. A. M., B. N. R.-L., Q. N., and J. K. participated in data analysis and interpretation of the results along with revision of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: M. G. R. holds research grants from Actelion, Gilead, United Therapeutics, Gossamer Bio, and Acceleron Pharma. B. N. R.-L. has served as consultant for Bayer and Gilead. B. N. R.-L. serves as site PI for clinical trial from Actelion. S. Y. C. has served as a consultant for Zogenix, Vivus, Aerpio, and United Therapeutics; S. Y. C. is a director, officer, and shareholder in Numa Therapeutics; S. Y. C. holds research grants from Actelion and Pfizer. S. Y. C. has filed patent applications regarding the targeting of metabolism in pulmonary hypertension. None declared: H. P., C. M. K., A. H., M. T., J. V., G. V., M. A. S., A. D., M. A. M., Q. N., J. K., and M. N.

Role of sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: The authors thank M. Saul, O. Marroquin, and A. Althouse for expert guidance in extraction and analysis of clinical bioinformatic data from the electronic health record system at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The authors thank SciVelo and the Department of Biomedical Informatics (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine) for data support. The authors thank the Pulmonary Hypertension Association for offering the designation of Specialty Care Center to the UPMC Presbyterian Hospital. The authors acknowledge the Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) for mortality data via NIH grant UL1 TR001857.

Additional information: The e-Appendix and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Drs Pi and Kosanovich contributed equally to this manuscript.

FUNDING/SUPPORT:National Institutes of Health [R01 HL124021, HL 122596, HL 138437, and UH2 TR002073]; American Heart Association [18EIA33900027] (S. Y. C.).

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Thenappan T., Ryan J.J., Archer S.L. Evolving epidemiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(8):707–709. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1266ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mair K.M., Johansen A.K.Z., Wallace E., MacLean M.R. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: basis of sex differences in incidence and treatment response. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171(3):567–579. doi: 10.1111/bph.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badesch D.B., Raskob G.E., Elliott C.G. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline characteristics from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2010;137(2):376–387. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Alonzo G.E., Barst R.J., Ayres S.M. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(5):343–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron B.A., Galiè N. Pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis, treatment, and clinical management in the contemporary era. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(9):1056–1065. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pauwaa S., Machado R.F., Desai A.A. Survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a brief review of registry data. Pulm Circ. 2011;1(3):430–431. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.87314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galiè N., Barerà J., Frost A., AMBITION Investigators Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):834–844. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghofrani H.A., Widermann R., Rose F. Combination therapy with oral sildenafil and inhaled iloprost for severe pulmonary hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(7):515–522. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-7-200204020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoeper M.M., Faulenbach C., Golpon H., Winkler J., Welte T., Niedermeyer J. Combination therapy with bosentan and sildenafil in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(6):1007–1010. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00051104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humbert M., Barst R.J., Robbins I.M. Combination of bosentan with epoprostenol in pulmonary arterial hypertension: BREATHE-2. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(3):353–359. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00028404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeper M.M., Markevych I., Spiekerkoetter E., Welte T., Niedermeyer J. Goal-oriented treatment and combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):858–863. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00075305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown L.M., Chen H., Halpern S. Delay in recognition of pulmonary arterial hypertension. factors identified from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2011;140(1):19–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strange G., Gabbay E., Kermeen F. Time from symptoms to definitive diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: the DELAY study. Pulm Circ. 2013;3(1):89–94. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.109919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deaño R., Glassner-Kolmin C., Rubenfire M. Referral of patients with pulmonary hypertension diagnoses to tertiary pulmonary hypertension centers: the multicenter RePHerral study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):887–893. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGoon M., Gutterman D., Steen V. Screening, early detection, and diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126(1 suppl):14S–34S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1_suppl.14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbs J.S.R. Making a diagnosis in PAH. Eur Respir Rev. 2007;16(102):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humbert M., Sitbon O., Chaouat A. Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Circulation. 2010;122(2):156–163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barst R.J., Gibbs J.S., Ghofrani H.A. Updated evidence-based treatment algorithm in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(10):S78–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin L.J. Introduction: diagnosis and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126(1 suppl):7S–10S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1_suppl.7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badesch D.B., Abman S.H., Simonneau G., Rubin L.J., McLaughlin V.V. Medical therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: updated ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131(6):1917–1928. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galiè N., Humbert M., Vachiéry J.L., ESC Scientific Document Group 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(1):67–119. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahay S., Melendres-Groves L., Pawar L., Cajigas H.R. Pulmonary hypertension care center network: improving care and outcomes in pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2017;151(4):749–754. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yount R.J., Vries J.K., Councill C.D. The medical archival system: an information retrieval system based on distributed parallel processing. Info Process Manag. 1991;27(4):379–389. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanderpool R.R., Saul M., Nouraie M., Gladwin M.T., Simon M.A. Association between hemodynamic markers of pulmonary hypertension and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(4):298–306. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonneau G., Gatzoulis M.A., Adatia I. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 suppl):D34–D41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoeper M.M., Bogaard H.J., Condliffe R. Definitions and diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 suppl):D42–D50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simonneau G., Montani D., Celermajer D.S. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801913. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Census Bureau 2010 American Community Survey: American FactFinder. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t?

- 29.Lederer D.J., Bell S.C., Branson R.D. Control of confounding and reporting of results in casual inference studies. guidance for authors from editors of respiratory, sleep, and critical care journals. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(1):22–28. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-564PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moons K.G., Altman D.G., Reitsma J.B. Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):W1–W73. doi: 10.7326/M14-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Humbert M., Sitbon O., Yaïci A., French Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Network Survival in incident and prevalent cohorts of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(3):549–555. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00057010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller D.P., Farber H.W., Poms A.W. Five-year outcomes of the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) Disease Management (REVEAL) [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:A4741. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delcroix M., Spaas K., Quarck R. Long-term outcome in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a plea for earlier parenteral prostacyclin therapy. Eur Respir Rev. 2009;18(114):253–259. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00003109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klinger J., Elliott C.G., Levine D.J. Therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults: update of the CHEST guidelines and expert panel report. Chest. 2019;155(3):565–586. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hay B.R., Pugh M.E., Robbins I.M., Hemnes A.R. Parenteral prostanoid use at a tertiary referral center: a retrospective cohort study. Chest. 2016;149(3):660–666. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakinala M., McGoon M. Pulmonary hypertension care centers. Adv Pulm Hypertens. 2014;12(4):175–178. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandras S.A., Ventura H.O., Corris P.A. Breaking down the barriers: why the delay in referral for pulmonary arterial hypertension? Ochsner J. 2016;16(3):257–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wapner J., Matura L.A. An update on pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Nurse Pract. 2015;11(5):551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.George M.P., Champion H.C., Pilewski J.M. Lung transplantation for pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2011;1(2):182–191. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.83455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long J., Russo M.J., Muller C., Vigneswaran W.T. Surgical treatment of pulmonary hypertension: lung transplantation. Pulm Circ. 2011;1(3):327–333. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.87297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLaughlin V.V., Shah S.J., Souza R., Humbert M. Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(18):1976–1997. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyamoto S., Nagaya N., Satoh T. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: comparison with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2 Pt 1):487–492. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9906015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simakova M., Kazimli A., Rygkov A., Naimushin A., Moiseeva O. Simple, non-invasive methods to assess severity of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(59 suppl):PA3792. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sajkov D., McEvoy R.D. Obstructive sleep apnea and pulmonary hypertension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51(5):363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu W.H., Yang L., Peng F.H. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with worse outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):303–310. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1290OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGoon M.D., Benza R.L., Escribano-Subias P. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: epidemiology and registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 suppl):D51–D59. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoeper M.M., Simon R., Gibbs J. The changing landscape of pulmonary arterial hypertension and implications for patient care. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(134):450–457. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jansa P., Jarkovsky J., Al-Hiti H. Epidemiology and long-term survival of pulmonary arterial hypertension in the Czech Republic: a retrospective analysis of a nationwide registry. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14(45):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ling Y., Johnson M.K., Kiely D.G. Changing demographics, epidemiology, and survival of incident pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the pulmonary registry of the United Kingdom and Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(8):790–796. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0383OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hurdman J., Condliffe R., Elliot C.A. ASPIRE registry: assessing the spectrum of pulmonary hypertension identified at a referral centre. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(4):945–955. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00078411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vachiéry J.L., Tedford R., Rosenkranz S. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801897. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01897-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suntharalingam J., Ross R.M., Easaw J., Robinson G., Coghlan G. Who should be referred to a specialist pulmonary hypertension centre: a referrer’s guide. Clin Med. 2016;16(2):135–141. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-2-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delcroix M., Kerr K., Fedullo P. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(3 suppl):S201–S206. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-621AS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lang I.M., Madani M. Update on chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2014;130(6):508–518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chemla D., Castelain V., Hervé P., Lecarpentier Y., Brimioulle S. Haemodynamic evaluation of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(5):1314–1331. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00068002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosenkranz S., Preston I.R. Right heart catheterization: best practice and pitfalls in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24(134):642–652. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0062-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benza R.L., Gomberg-Maitland M., Miller D.P. The REVEAL Registry risk score calculator in patients newly diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2012;141(2):354–362. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sitbon O., Benza R.L., Badesch D.B. Validation of two predictive models for survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(1):152–164. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00004414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gillmeyer K.R., Lee M.M., Link A.P., Klings E.S., Rinne S.T. Accuracy of algorithms to identify pulmonary arterial hypertension in administrative data. Chest. 2019;155(4):680–688. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.