Abstract

Background

Portable monitoring is a convenient means for diagnosing sleep apnea. However, data on whether one night of monitoring is sufficiently precise for the diagnosis of sleep apnea are limited.

Research Question

The current study sought to determine the variability and misclassification in disease severity over three consecutive nights in a large sample of patients referred for sleep apnea.

Methods

A sample of 10,340 adults referred for sleep apnea testing was assessed. A self-applied type III monitor was used for three consecutive nights. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was determined for each night, and a reference AHI was computed by using data from all 3 nights. Pairwise correlations and the proportion misclassified regarding disease severity were computed for each of the three AHI values against the reference AHI.

Results

Strong correlations were observed between the AHI from each of the 3 nights (r = 0.87-0.89). However, substantial within-patient variability in the AHI and significant misclassification in sleep apnea severity were observed based on any 1 night of monitoring. Approximately 93% of the patients with a normal study on the first night and 87% of those with severe sleep apnea on the first night were correctly classified compared with the reference derived from all three nights. However, approximately 20% of the patients with mild and moderate sleep apnea on the first night were misdiagnosed either as not having sleep apnea or as having mild disease, respectively.

Conclusions

In patients with mild to moderate sleep apnea, one night of portable testing can lead to misclassification of disease severity given the substantial night-to-night variability in the AHI.

Key Words: home sleep apnea test, portable monitoring, sleep apnea

Abbreviation: AHI, apnea-hypopnea index

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 33

Sleep apnea is a relatively common disorder, with prevalence estimates of 9% to 38% in the general population.1,2 Untreated sleep apnea is associated with clinical consequences, including incident hypertension,3 cardiovascular disease,4 stroke,5 and all-cause mortality.6 Moreover, patients with undiagnosed sleep apnea have higher rates of health-care utilization and impose substantial added medical costs annually in the United States.7 Although there is an increasing awareness of sleep apnea among health-care professionals, it remains frequently underdiagnosed, even in patients with moderate to severe disease.8, 9, 10 With advancements in technology, portable monitoring for sleep apnea is now feasible and has circumvented many of the limitations of in-laboratory testing.

Regardless of whether an in-laboratory polysomnogram or home sleep apnea test is performed, an important consideration in interpreting the data is night-to-night variability.11, 12, 13 It is well established that on the first night in a sleep laboratory, normal subjects and patients with sleep disorders exhibit alterations in sleep quality that are not necessarily alleviated by the use of a home monitor.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Thus, both environment- and patient-related factors are potential sources of night-to-night variability. Research on the use of in-laboratory polysomnography and portable monitoring in adult patients with sleep apnea has shown that a single night of monitoring may be insufficient for a precise determination of disease severity and could misclassify a significant proportion of those affected.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 In light of the convenience associated with the use of portable monitors, empirical evidence is needed to determine the variability in assessing sleep apnea severity based on multi-night testing, which is more convenient and practical in the home. Thus, the current study sought to determine the variability and misclassification in disease severity by using a portable sleep apnea monitor over 3 consecutive nights in a large sample of patients referred for sleep apnea. It was hypothesized that there would be considerable night-to-night variability in the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), particularly in those with mild to moderate sleep apnea.

Patients and Methods

Study Sample

The study sample consisted of patients referred to a certified independent diagnostic testing facility (NovaSom, Inc.) for a type III sleep study for the evaluation of sleep apnea. The criteria proposed for home testing by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine were applied to delineate whether home testing was appropriate.33 Per the recommended guidelines, patients with significant comorbid medical conditions such as moderate to severe COPD, neuromuscular disease, or congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class III or IV) were not eligible. Each patient was required to have at least one or more symptoms suggestive of sleep apnea such as excessive sleepiness, witnessed apneas, reports of daytime napping, falling asleep at work or while driving, or witnessed nocturnal motor activities. Exclusionary criteria included ongoing or previous treatment with continuous positive pressure therapy, upper airway surgery, or use of supplemental oxygen. Demographic information was obtained from all patients along with self-reported daytime sleep tendency using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.34

Of the 12,325 eligible patient referrals available for analysis, 976 patients did not have data for all three nights of monitoring and an additional 1,009 patients had < 2 h of recording on any night. Exclusion of the 1,985 (16.1%) patients resulted in an analysis sample of 10,340 patients. No significant differences in demographic variables such as age, sex, race, BMI, or self-reported sleepiness were noted between the included vs excluded patients. Approval for analysis of the de-identified clinical data was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University (IRB00223097).

Home Sleep Apnea Test

A portable monitor (AccuSom; NovaSom, Inc.), which has been previously validated against full polysomnography,35 was shipped to each patient following a telephone call from the central facility to review the testing protocol, device operation, and sensor placement. The monitor recorded the following physiologic signals: oxyhemoglobin saturation, oronasal airflow using an acoustic sensor, and chest excursion using an effort belt. The monitor was programmed to collect data until the patient stopped the recording or for a maximum of 8 h. Each patient was required to provide 3 nights of recording. A computerized algorithm within the monitor would alert the patient if the quality of any signal was suboptimal, allowing the patient to reapply or adjust the sensor.

The recorded data from each night were downloaded to a central repository and linked to the patient’s demographic and clinical data. The digital recordings were subjected to an automated algorithm for scoring of apneas and hypopneas in accordance with standard criteria.36 An apnea was defined as a reduction in airflow of ≥ 90%, lasting for ≥ 10 s. The apnea was defined as obstructive unless the chest effort during the event fell to ≤ 10% of the prevailing effort baseline. A hypopnea was defined as a reduction in airflow of ≥ 50%, lasting for ≥ 10 s, and having a corresponding drop in oxyhemoglobin saturation of 4%. To determine the AHI, the number of apneas and hypopneas was divided by the total recording time. The results from the automated scoring were initially reviewed by a registered technologist and then by a medical provider certified in sleep medicine.

Statistical Analyses

The variable of interest was the AHI derived from each of three nights of home testing. The level of concordance in the AHI across nights was estimated by using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). Because repeat measurements reduce imprecision, a reference AHI value was computed based on the individual values derived from the three nights. Specifically, the reference AHI was obtained as the posterior mean given the data and a measurement error model.37 The model assumes that the observed AHI for each night is independently drawn from a gamma distribution, assuming the “true” unknown AHI. Most variables in medicine, such as the AHI, are nonstationary stochastic; thus, the posterior mean was used because it likely represents the “average” degree of exposure to apneas and hypopneas across multiple nights.

Agreement between the AHI from each night with the reference AHI was examined by using Bland-Altman analysis.38 This method consists of calculating the difference between the AHI from a specific night (AHIi, where i = 1, 2, or 3) and the reference AHI value. The difference (AHIi – AHIr) was plotted against the reference AHI value (AHIr), and the limits of agreement were defined as ±1.96 SD of the mean difference. Finally, the presence and severity of sleep apnea were defined based on individual and reference AHI values using the following thresholds: < 5.0 (normal), 5.0 to 14.9 (mild), 15.0 to 29.9 (moderate), and ≥ 30.0 (severe). Cross-tabulations were used to examine the degree of misclassification of disease status (presence vs absence) and disease severity (mild, moderate, and severe) between a specific night and the reference AHI value. Statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.), R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.r-project.org/), and WinBUGS statistical software packages.

Results

The study sample consisted of 10,340 patients referred for home sleep apnea testing (mean, 64.7%). The average age was 54.0 years (range, 21.0-95.0 years), and the mean BMI was 33.0 kg/m2 (range, 15.2-86.0 kg/m2). The race distribution of the sample was as follows: white, 73.6%; black, 9.8%; Asian, 1.9%; other, 2.0%; and missing, 12.7%. More than 61% of the patient referrals were either from general practitioners or internists; the remaining two-thirds of the patient sample were referred from pulmonologists (12.3%), sleep specialists (10.5%), otolaryngologists (9.4%), or other medical disciplines (6.1%). The average AHI values in the sample for the first, second, and third night were 15.6 events/h (range, 0.0-150.8 events/h), 15.7 events/h (range, 0.0-141.1 events/h), and 15.6 events/h (range, 0.0-141.0 events/h), respectively. The within-patient average and SD of the AHI values across the three nights were 15.6 and 4.4 events/h, respectively.

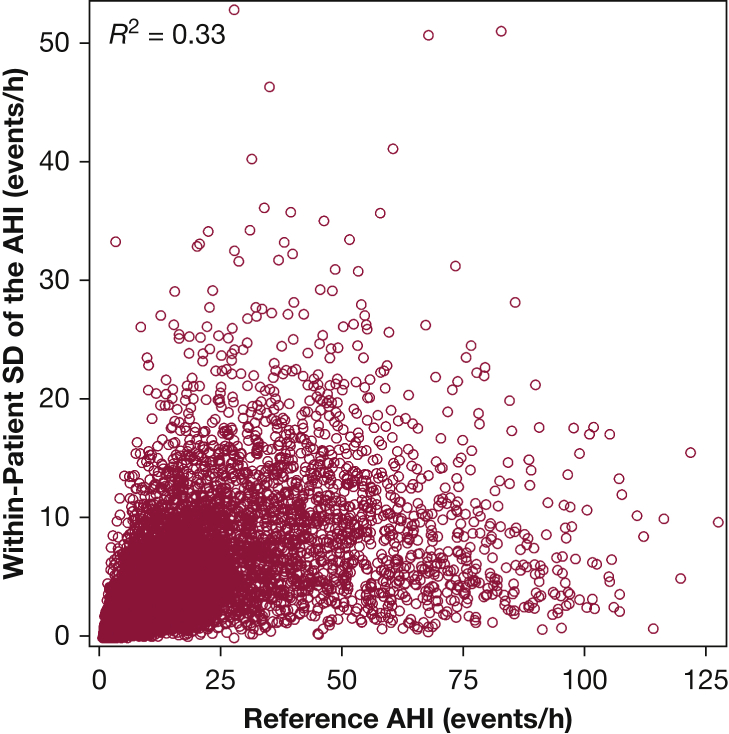

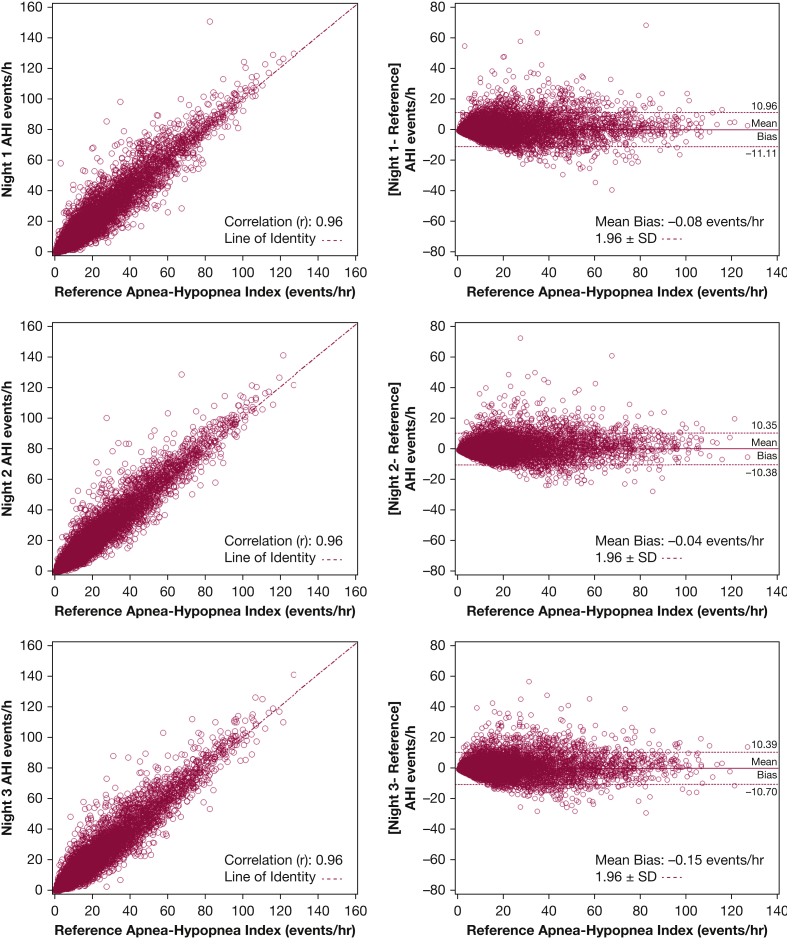

The association between the AHI values across the three nights was strong and relatively consistent: night 1 vs night 2, r = 0.89 (95% CI, 0.88-0.90); night 1 vs night 3, r = 0.87 (95% CI, 0.86-0.88); and night 2 vs night 3, r = 0.89 (95% CI, 0.88-0.90). Despite the strong correlations in AHI across nights, there was substantial within-patient variability in the AHI values (average SD, 4.4 events/h). The within-patient variability in AHI was related to the reference AHI value from the 3 nights (Fig 1). Approximately 33% of the variance in the within-patient night-to-night AHI variability could be attributed to the reference AHI (r2 = 0.33). Bland-Altman plots, which compare a specific night’s AHI vs the reference AHI, are shown along with the bivariate plots in Figure 2. The mean difference between the AHI values from nights 1, 2, and 3 and the reference AHI was 0.01 (SD, 5.5), 0.05 (SD, 5.0), and –0.06 (SD, 5.3) events/h, respectively. Although there was no systematic bias between any one night and the overall reference AHI, the limits of agreement (±1.96 SD) were wide: night 1, 11.0 to –11.1 events/h; night 2, 10.3 to –10.4 events/h; and night 3, 10.4 to –10.7 events/h. Furthermore, approximately 5.8%, 5.8%, and 6.2% of the study sample was outside the ±1.96 SD limits for nights 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Within-patient SD of the AHI vs the reference AHI values derived from the 3 nights of home sleep testing. AHI = apnea-hypopnea index.

Figure 2.

Pairwise and Bland-Altman plots of the AHI from the three nights of home sleep testing. The dashed lines in the plots on the left represent lines of identity. The dashed lines in the plots on the right represent the limits of agreement (mean bias ± 1.96 SD). See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Using the reference AHI, the distribution of disease severity was as follows: 2,957 patients (28.6%) did not have sleep apnea, 3,885 patients (37.6%) had mild disease, 1,963 (19.0%) had moderate disease, and 1,535 (14.9 %) had severe disease. Comparisons of patients within each group based on the reference AHI vs that of individual night AHI values are shown in Table 1. Of the 3,885 patients with mild disease based on the reference AHI, 895 (23.0%), 886 (22.8%), and 895 (23.0%) patients were labeled as not having sleep apnea based on the first, second, and third night’s AHI, respectively. Of the 1,963 patients having moderate disease using the reference AHI, 447 (22.3%), 412 (21.0%), and 440 (22.4%) were classified as having mild sleep apnea for the three nights. Thus, if only one night of home sleep monitoring had been performed, approximately 23% of patients with mild disease would be misdiagnosed as not having sleep apnea and approximately 22.0% of patients with moderate disease would be diagnosed as having mild sleep apnea.

Table 1.

Disease Severity Comparing the AHI From Each of the 3 Nights vs the Reference AHI

| AHI (events/h) | Reference AHI (events/h) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5.0 (n = 2,957) | 5.0-14.9 (n = 3,885) | 15.0-29.9 (n = 1,963) | ≥ 30.0 (n = 1,535) | |

| Night 1 | ||||

| < 5.0 | 2,780 (94.02%)a | 895 (23.04%) | 1 (0.05%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 5.0-14.9 | 176 (5.95%) | 2592 (66.72%)a | 447 (22.77%) | 4 (0.26%) |

| 15.0-29.9 | 0 (0.00%) | 387 (9.96%) | 1,240 (63.17%)a | 169 (11.01%) |

| ≥ 30 | 1 (0.03%) | 11 (0.28%) | 275 (14.01%) | 1,362 (88.73%)a |

| Night 2 | ||||

| < 5.0 | 2,769 (93.64%)a | 886 (22.80%) | 3 (0.15%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 5.0-14.9 | 187 (6.32%) | 2,623 (67.52%)a | 412 (20.99%) | 1 (0.07%) |

| 15.0-29.9 | 1 (0.03%) | 361 (9.29%) | 1,293 (65.87%)a | 154 (10.03%) |

| ≥ 30 | 0 (0.00%) | 15 (0.39%) | 255 (12.99%) | 1,380 (89.90%)a |

| Night 3 | ||||

| < 5.0 | 2,725 (92.15%)a | 895 (23.04%) | 9 (0.46%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 5.0-14.9 | 228 (7.71%) | 2,617 (67.36%)a | 440 (22.41%) | 5 (0.33%) |

| 15.0-29.9 | 4 (0.14%) | 359 (9.24%) | 1,232 (62.76%)a | 184 (11.99%) |

| ≥ 30 | 0 (0.00%) | 14 (0.36%) | 282 (14.37%) | 1,346 (87.69%)a |

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index.

Represents agreement between the AHI from 1 night compared with the reference AHI. Entries above and below these noted entries represent underclassification and overclassification of disease severity, respectively, compared with the reference AHI.

A single night of sleep recording was also associated with overdiagnosis. Of the 2,957 patients without sleep apnea based on the reference AHI, 176 (6.0%), 187 (6.3%), and 228 (7.7%) were classified as having mild disease using the AHI from the first, second, and third night, respectively. Similarly, of the 3,885 patients with mild sleep apnea based on the reference AHI, 387 (10.0%), 361 (9.3%), and 359 (9.2%) were classified as having moderate disease for the 3 nights, respectively (Table 1). A similar pattern of misclassification was also seen in those with moderate disease. Collectively, the greatest misclassification (underassessment and overassessment of disease severity) occurred in patients with mild to moderate sleep apnea. Interestingly, there was no evidence of a first night effect, given that the degree of misclassification was similar across the three nights.

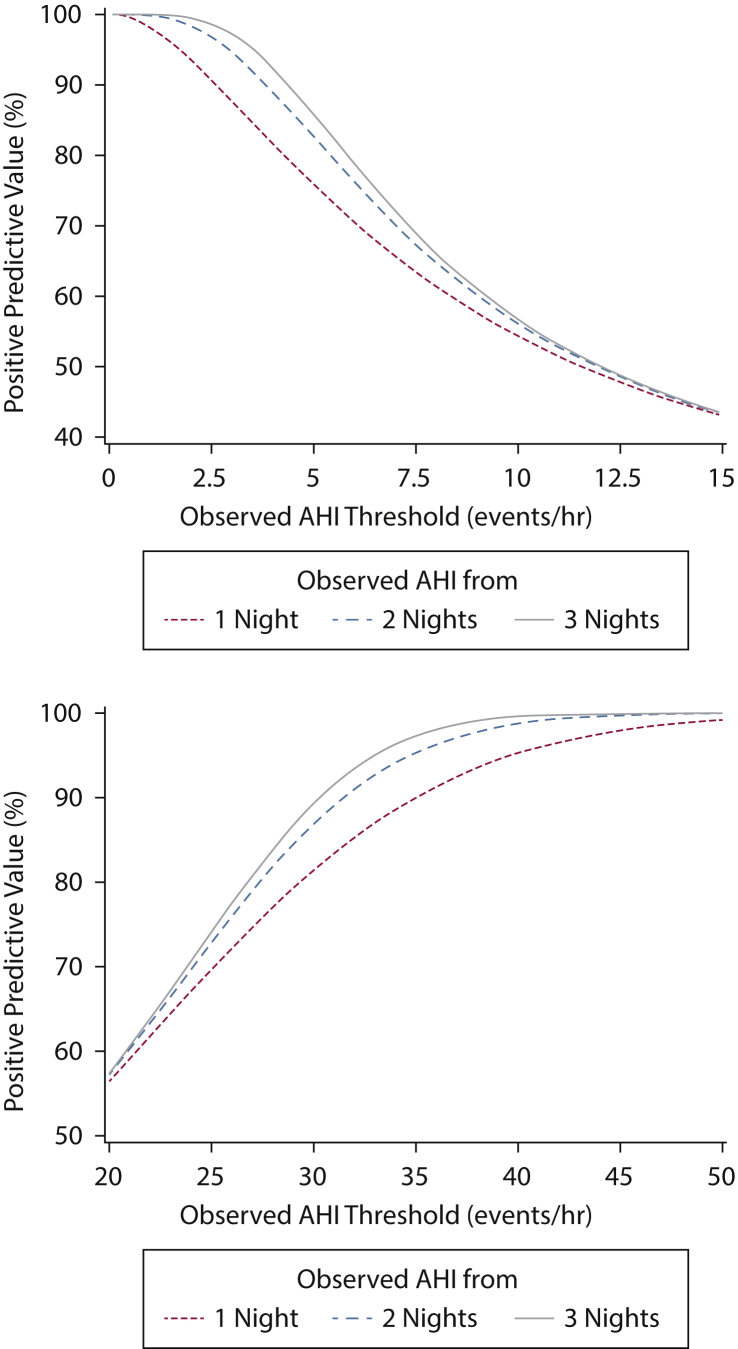

Considering that the thresholds of 5 and 30 events/h are used to define mild and severe sleep apnea, respectively, several test characteristics were determined by using the reference AHI. Specifically, sensitivity and specificity of identifying those without sleep apnea and those with severe disease were determined assuming that the observed average AHI from the first night, first and second nights, and all three nights is < 5 events/h and ≥ 30 events/h (Table 2). Based on the derived positive predictive values, for a patient without sleep apnea on the first night (observed AHI < 5 events/h), the probability of not having sleep apnea is 75.8% (95% CI, 74.2-77.3). The probability of not having sleep apnea increases to 82.6% and 85.9% if the observed average AHI from the first 2 nights and from all 3 nights is < 5 events/h, respectively. Moreover, for a patient with severe disease on the first night (≥ 30 events/h), the probability of having severe sleep apnea is 81.5% (95% CI, 79.7-83.1). The probabilities for severe disease increase to 86.9% and 89.4% if the average observed AHI values from first 2 nights and all 3 nights also demonstrate severe sleep apnea. Figure 3 displays the positive predictive values for not having sleep apnea (< 5 events/h) and having severe sleep apnea (≥ 30 events/h) as a function of the observed AHI determined from the first night, first two nights, and all three nights being above a specific threshold.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, Specificity, PPVs, and NPVs for a Reference AHI < 5 events/h and ≥ 30 events/h

| Reference AHI | Nights Averaged | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5 events/h | |||||

| 1 | 87.9 (87.1-88.6) | 91.0 (90.4-91.6) | 75.8 (74.2-77.3) | 95.1 (94.6-95.5) | |

| 1, 2 | 91.9 (91.2-92.5) | 93.9 (93.4-94.4) | 82.6 (91.2-84.1) | 96.0 (95.5-96.4) | |

| 1, 2, 3 | 93.7 (93.2-94.3) | 95.2 (94.7-95.6) | 85.9 (84.5-87.2) | 96.5 (96.1-96.9) | |

| ≥ 30 events/h | |||||

| 1 | 88.7 (87.2-90.3) | 95.6 (95.1-96.0) | 81.5 (79.7-83.1) | 96.4 (95.9-96.7) | |

| 1, 2 | 94.7 (93.4-95.7) | 96.9 (96.5-97.3) | 86.9 (85.4-88.4) | 97.3 (97.0-97.7) | |

| 1, 2, 3 | 99.6 (99.3-99.6) | 97.5 (97.2-97.8) | 89.3 (87.9-90.7) | 97.8 (97.5-98.1) |

Point estimates were determined by using the average AHI from 1, 2, and 3 nights of monitoring being < 5 events/h and ≥ 30 events/h. NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Figure 3.

Positive predictive values for an AHI < 5 events/h (top panel) and for an AHI > 30 events/h (bottom panel) for average AHI from 1, 2, and 3 nights of observation. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

To determine the changes in classification of disease severity based on multi-night testing, patients underdiagnosed (n = 1,516) on the first night relative to the reference AHI were examined, and misclassification rates based on additional nights of testing were then determined. Approximately 40% of the patients (605 of 1,516) remained underdiagnosed, with a majority of the patients with mild disease still being classified as normal based on the two additional nights of monitoring. Of the 850 overdiagnosed patients based on the first night, 32.9% remained overdiagnosed despite having two additional nights of testing.

Discussion

The results of the current study, the largest to date on multi-night home testing for sleep apnea, show that there is considerable night-to-night variability in the assessment of breathing abnormalities during sleep. This variability undoubtedly has important implications regarding whether a patient is diagnosed as having sleep apnea and whether the patient has mild, moderate, or severe disease. In a large representative sample of patients referred for the evaluation of sleep apnea, a single night of monitoring was conclusive in a majority of patients if the first night revealed either normal breathing during sleep (< 5 events/h) or severe sleep apnea (≥ 30 events/h). Specifically, > 92% of patients with a normal first night and > 87% of the patients with severe sleep apnea on the first night were appropriately classified. In contrast, two-thirds of patients with mild and moderate disease, as assessed by the 3 nights of testing, would be accurately classified with 1 night of monitoring. The remaining one-third would be either underdiagnosed or overdiagnosed. Given the relative ease of using a home portable monitor, a subset of patients at risk for sleep apnea may benefit from multi-night recording at home for precise ascertainment of disease severity.

Night-to-night variability in sleep apnea severity has important implications not only for the clinical diagnosis but also for estimating disease prevalence in epidemiologic studies. Thus, it is not surprising that the issue of whether 1 night of monitoring is sufficient has been a topic of significant debate. Although a number of previous studies20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 have specifically examined the variability in sleep apnea severity over consecutive and nonconsecutive nights, the findings across these studies have been generally inconsistent. As a result, some have advocated the use of just one night of monitoring,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 whereas others have recommended a more cautious approach of considering additional monitoring when the clinical history is suggestive of sleep apnea but the initial diagnostic evaluation is unrevealing.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Such discrepancy in recommendations is to be expected given that most of the available data are based on small study samples, which have considerable interpatient heterogeneity. Furthermore, the variability in the methods used to record, score, and quantify sleep apnea severity across the available studies could further contribute to discrepancies across available studies and therefore limits the ability to reach a generalizable consensus regarding multi-night testing.

Despite recognizing all of the potential limitations of overdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of disease severity with one night of polysomnography, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine39 has previously recommended that a single night of recording is sufficient for the diagnosis of sleep apnea. However, guidelines should be interpreted in the context of conducting a full montage in-laboratory polysomnogram. At present, there are a limited number of studies looking at the value of multi-night testing with a home portable monitor for the diagnosis of sleep apnea, particularly in a large representative sample of patients at risk. Our results confirm previous findings showing more inter-night variability in metrics of sleep apnea in persons with mild disease.11,13,40,41 Because home portable monitoring provides a simple and less expensive alternative to an in-laboratory study, it is imperative that studies examining different approaches of deploying such technologies be conducted to establish optimal ways of using them in everyday clinical practice. The results provided here also show that portable monitoring with multi-night testing is particularly valuable in defining the variability in sleep apnea severity across multiple nights.

One of the major assumptions of this study was the use of a composite index of disease severity based on all three nights as the reference standard. It could be easily argued that any one night or even the maximum value that is diagnostic for sleep apnea should be used as the reference. Indeed, in clinical practice, one night is used for making decisions regarding diagnosis and therapy. Even epidemiologic studies such as the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study42 and the Sleep Heart Health Study43 have exclusively used a single night of polysomnography for assessing disease severity. With only one measurement that is subject to modest variation, estimates of relative risks (or ORs) for health outcomes from epidemiologic studies could be affected. The use of multiple measurements is common practice in many areas of clinical medicine (eg, hypertension) and is also universally incorporated in observational research and clinical trials because of the intraindividual variation and associated measurement error. Thus, the issue of disease misclassification is not trivial: it not only can change how a particular patient is clinically assessed and managed but it can also influence our understanding of the public health implications of the disease process.

There are several strengths to this study. First, the analyses presented were based on a large study sample with substantial regional representation across the United States. Thus, the inferences are generalizable to patients at risk for sleep apnea. Second, the use of a self-applied monitor with built-in automated quality control measures that identified poorly placed sensors at the time of self-application provided a robust yet simple monitoring system that can be readily deployed in clinical practice. Third, automated scoring of the sleep recordings with subsequent review by trained personnel provided a systematic approach that minimized the variability commonly associated with manual scoring. Finally, collecting three nights of data at home in a large sample size provided valuable information on the potential insights gained from multi-night testing. Although a few studies with smaller sample sizes have collected more than two nights of data,11,17,40,41 previous research on night-to-night variability of sleep apnea has generally been based on two nights. Having multiple nights of testing helped not only clarify the issue of night-to-night variability but also provided insight into whether additional nights improve diagnostic yield for sleep apnea.

The current study also has several limitations. These include lack of physiological recordings of oronasal airflow, body position, or sleep. Although having such measurements would have helped refine the estimates of disease severity, the portable monitor used was convenient for self-application in the home setting. Other limitations include the lack of information on other patient-related factors such as alcohol intake or use of sedative medications, which could certainly contribute to night-to-night variability of AHI. However, the influence of such factors is likely to be nondifferential across categories of sleep apnea severity. Finally, the use of a minimum threshold of 2 h of recording time could certainly also contribute to night-to-night variability, particularly if the amount of sleep fluctuated across the three nights.

Given the growing demand to identify and treat sleep apnea in the general community, there is an urgent need for implementing appropriate methods for portable monitoring in the ambulatory setting. Multi-night portable monitoring clearly provides an alternative for additional diagnosing of sleep apnea that is accessible for all health-care professionals. A strategy that combines home monitoring with daily transmission of overnight data via wireless communication can be easily implemented. The results presented here indicate that multiple nights of monitoring provide a better understanding of the potential heterogeneity in disease severity, which may affect therapeutic decisions.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: N. M. P. is the guarantor of the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole from inception to published article. N. M. P., S. P., R. N. A. and C. C. were responsible for data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the development of the final manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: There was no role of sponsors in the development of the research or the manuscript.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grants K23-HL118414, R01-HL117167, and R01-HL146709].

References

- 1.Punjabi N.M. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):136–143. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senaratna C.V., Perret J.L., Lodge C.J. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hou H., Zhao Y., Yu W. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.010405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Floras J.S. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an enigmatic risk factor. Circ Res. 2018;122(12):1741–1764. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.310783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M., Hou W.S., Zhang X.W., Tang Z.Y. Obstructive sleep apnea and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172(2):466–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mashaqi S., Gozal D. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea and PAP therapy on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality based on age and gender—a literature review. Respir Investig. 2020;58(1):7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knauert M., Naik S., Gillespie M.B., Kryger M. Clinical consequences and economic costs of untreated obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;1(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa L.E., Uchoa C.H., Harmon R.R., Bortolotto L.A., Lorenzi-Filho G., Drager L.F. Potential underdiagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea in the cardiology outpatient setting. Heart. 2015;101(16):1288–1292. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapur V., Strohl K.P., Redline S., Iber C., O'Connor G., Nieto J. Underdiagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome in U.S. communities. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(2):49–54. doi: 10.1007/s11325-002-0049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young T., Evans L., Finn L., Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20(9):705–706. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad B., Usmani S., Steffen A.D. Short-term variability in apnea-hypopnea index during extended home portable monitoring. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):855–863. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoberl A.S., Schwarz E.I., Haile S.R. Night-to-night variability of obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2017;26(6):782–788. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sforza E., Roche F., Chapelle C., Pichot V. Internight variability of apnea-hypopnea index in obstructive sleep apnea using ambulatory polysomnography. Front Physiol. 2019;10:849. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toussaint M., Luthringer R., Schaltenbrand N. First-night effect in normal subjects and psychiatric inpatients. Sleep. 1995;18(6):463–469. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wohlgemuth W.K., Edinger J.D., Fins A.I., Sullivan R.J., Jr. How many nights are enough? The short-term stability of sleep parameters in elderly insomniacs and normal sleepers. Psychophysiology. 1999;36(2):233–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzo J.L., Barbanoj M.J. Variability of sleep parameters across multiple laboratory sessions in healthy young subjects: the "very first night effect.". Psychophysiology. 2002;39(4):409–413. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng H., Sowers M., Buysse D.J. Sources of variability in epidemiological studies of sleep using repeated nights of in-home polysomnography: SWAN Sleep Study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(1):87–96. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veauthier C., Piper S.K., Gaede G., Penzel T., Paul F. The first night effect in multiple sclerosis patients undergoing home-based polysomnography. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:337–344. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S176201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aber W.R., Block A.J., Hellard D.W., Webb W.B. Consistency of respiratory measurements from night to night during the sleep of elderly men. Chest. 1989;96(4):747–751. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.4.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ancoli-Israel S., Kripke D.F., Mason W., Messin S. Comparisons of home sleep recordings and polysomnograms in older adults with sleep disorders. Sleep. 1981;4(3):283–291. doi: 10.1093/sleep/4.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bliwise D.L., Carey E., Dement W.C. Nightly variation in sleep-related respiratory disturbance in older adults. Exp Aging Res. 1983;9(2):77–81. doi: 10.1080/03610738308258429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chediak A.D., Cevedo-Crespo J.C., Seiden D.J., Kim H.H., Kiel M.H. Nightly variability in the indices of sleep-disordered breathing in men being evaluated for impotence with consecutive night polysomnograms. Sleep. 1996;19(7):589–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.7.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean R.J., Chaudhary B.A. Negative polysomnogram in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1992;101(1):105–108. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Littner M. Polysomnography in the diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: where do we draw the line? Chest. 2000;118(2):286–288. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lord S., Sawyer B., O'Connell D. Night-to-night variability of disturbed breathing during sleep in an elderly community sample. Sleep. 1991;14(3):252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maestri R., La Rovere M.T., Robbi E., Pinna G.D. Night-to-night repeatability of measurements of nocturnal breathing disorders in clinically stable chronic heart failure patients. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(4):673–678. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendelson W.B. Use of the sleep laboratory in suspected sleep apnea syndrome: is one night enough? Cleve Clin J Med. 1994;61(4):299–303. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.61.4.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer T.J., Eveloff S.E., Kline L.R., Millman R.P. One negative polysomnogram does not exclude obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1993;103(3):756–760. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosko S.S., Dickel M.J., Ashurst J. Night-to-night variability in sleep apnea and sleep-related periodic leg movements in the elderly. Sleep. 1988;11(4):340–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newell J., Mairesse O., Verbanck P., Neu D. Is a one-night stay in the lab really enough to conclude? First-night effect and night-to-night variability in polysomnographic recordings among different clinical population samples. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quan S.F., Griswold M.E., Iber C. Short-term variability of respiration and sleep during unattended nonlaboratory polysomnography—the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2002;25(8):843–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wittig R.M., Romaker A., Zorick F.J., Roehrs T.A., Conway W.A., Roth T. Night-to-night consistency of apneas during sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129(2):244–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collop N.A., Anderson W.M., Boehlecke B. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin. Sleep Med. 2007;3(7):737–747. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johns M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reichert J.A., Bloch D.A., Cundiff E., Votteri B.A. Comparison of the NovaSom QSG, a new sleep apnea home-diagnostic system, and polysomnography. Sleep Med. 2003;4(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iber C., Ancoli-Israle S., Chesson A.L., Quan S.F. 1 ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Weschester, IL: 2007. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefanski L.A. Measurement error models. J Am Statistic Assoc. 2012;95(452):1353–1358. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bland J.M., Altman D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapur V.K., Auckley D.H., Chowdhuri S. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479–504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bittencourt L.R., Suchecki D., Tufik S. The variability of the apnoea-hypopnoea index. J Sleep Res. 2001;10(3):245–251. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aarab G., Lobbezoo F., Hamburger H.L., Naeije M. Variability in the apnea-hypopnea index and its consequences for diagnosis and therapy evaluation. Respiration. 2009;77(1):32–37. doi: 10.1159/000167790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young T., Palta M., Dempsey J., Skatrud J., Weber S., Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Redline S., Sanders M.H., Lind B.K. Methods for obtaining and analyzing unattended polysomnography data for a multicenter study. Sleep Heart Health Research Group. Sleep. 1998;21(7):759–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]