Abstract

The present study aimed to determine the potential molecular mechanisms underlying p21 (RAC1)-activated kinase 7 (PAK7) expression in glioblastoma (GBM) and evaluate candidate prognosis biomarkers for GBM. Gene expression data from patients with GBM, including 144 tumor samples and 5 normal brain samples, were downloaded. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and messenger RNAs (mRNAs) were explored via re-annotation. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including differentially expressed mRNAs and differentially expressed lncRNAs, were investigated and subjected to pathway analysis via gene set enrichment analysis. The miRNA-lncRNA-mRNA interaction [competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA)] network was investigated and survival analysis, including of overall survival (OS), was performed on lncRNAs/mRNAs to reveal prognostic markers for GBM. A total of 954 upregulated and 1,234 downregulated DEGs were investigated between GBM samples and control samples. These DEGs, including PAK7, were mainly enriched in pathways such as axon guidance. ceRNA network analysis revealed several outstanding ceRNA relationships, including miR-185-5p-LINC00599-PAK7. Moreover, paraneoplastic antigen Ma family member 5 (PNMA5) and somatostatin receptor 1 (SSTR1) were the two outstanding prognostic genes associated with OS. PAK7 may participate in the tumorigenesis of GBM by regulating axon guidance, and miR-185-5p may play an important role in GBM progression by sponging LINC00599 to prevent interactions with PAK7. PNMA5 and SSTR1 may serve as novel prognostic markers for GBM.

Keywords: glioblastoma multiforme, p21 (RAC1) activated kinase 7, differentially expressed gene, pathway analysis, competing endogenous RNA, prognostic marker

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) represents 15% of all brain tumors (1). In the majority of cases, the length of survival following diagnosis is 12–15 months, with fewer than 3–5% of patients surviving for >5 years (2). In general, surgery after chemotherapy and radiation therapy are commonly used for GBM treatment (3). However, the cancer usually recurs, as there is no clear way to prevent the disease (4).

Improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying GBM at molecular and structural levels is valuable for clinical treatment (5). Bioinformatics may be effectively used to analyze GBM microarray data in order to provide a theoretical reference for further exploration of tumorigenic mechanisms and aid in searching for potential target genes (6). Based on bioinformatic studies, certain differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including p21 (RAC1)-activated kinase 7 (PAK7), were identified as potential therapeutic targets for glioma (7). As the longest member of the PAK family, PAK7 (renamed from PAK5) contains a total of eight protein-coding exons (8). PAK7, initially cloned as a brain-specific kinase, was hypothesized to be involved in neurite growth in neuronal cells (9,10). The downregulation of PAK7 expression was shown to inhibit glioma cell migration and invasion through competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks such as the PAK7-early growth response 1-matrix metalloproteinase 2 signaling pathway (11). The levels of PAK7 are regulated by microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) such as miR-129 and are associated with long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in glioma cell progression (12). However, the potential molecular mechanisms underlying PAK7 activity in GBM remain unclear.

In the present study, gene expression data from GBM were downloaded and reanalyzed using bioinformatic tools. The DEGs, including differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) and differentially expressed mRNAs (DEMs) between GBM samples and normal samples were investigated and subjected to functional and pathway enrichment analyses. PAK7-associated miRNAs were investigated and a PAK7-associated ceRNA network was constructed. Furthermore, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) survival analysis was performed to confirm the effect of PAK7 expression on GBM. The study aimed to reveal the potential molecular mechanisms underling PAK7 expression in GBM and identify candidate prognostic biomarkers for GBM.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

The RNA-seq profile data and clinical data of TCGA-GBM were downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) database (http://xena.ucsc.edu) based on the platform of Illumina HiSeq 2000 RNA Sequencing (Illumina, Inc.). A total of 144 tumor samples (GBM group) and five normal brain samples (control group) were enrolled in the present study.

Exploration of lncRNAs and mRNAs by re-annotation

An exon was defined as lncRNA or mRNA if its starting and ending positions (including the positive and negative chain) in the current RNAseq data were in accordance with the chromosome location annotation of lncRNA or mRNA (hg19, V25) in GENCODE database (https://www.gencodegenes.org/) (13), respectively.

Investigation of DEGs

Genes with low expression (expression value was 0 in >50% samples) were removed. Linear regression and empirical Bayesian methods (14,15) in Limma package of R (version: 3.40.2) (16) were used to explore DElncRNAs and DEMs. Multiple correction on the P-value of each DEG was performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (17) to obtain the adjusted P value. An adjusted P<0.05 and log|fold change| >1.5 were selected as the thresholds for DEG screening. A volcano plot was constructed based on the different expression values of DEMs and DElncRNAs.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) (18) was performed on DElncRNAs and DEMs using the vegan (version 2.5–2; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/) package (19) in R, followed by the construction of an NMDS plot. Analysis of similarities (20) was performed for sample similarity analysis. The distance between two points was defined as Bray-Curtis, and displacement tests were carried out. The threshold was set as P<0.05.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for PAK7

Pearson's correlation coefficients for all mRNA-PAK7 pairs were calculated and pathway analysis (21) was performed on these mRNA-PAK7 pairs (according to the descending order of the correlation coefficient) via GSEA in the clusterProfiler package of R (version: 3.12.0) (22). A value of P<0.05 was considered as the threshold for current analysis.

miRNA prediction and co-expression investigation

Pearson's correlation coefficients for all DElncRNA-PAK7 and DEM-PAK7 relations were calculated and correlation tests were performed. DElncRNAs and DEMs with |r| >0.6 and P<0.05 were considered as key genes that were significantly associated with PAK7. The correlation between lncRNAs and mRNAs was calculated with the methods mentioned above. miRNA predictions for DEMs that positively correlated with mRNAs (including PAK7) was performed using miRWalk2.0 software (23,24) and combined with the prediction results from six databases, including miRWalk, miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/) (25), miRDB (http://www.mirdb.org/) (26), miRMap (http://www.mirmap.ezlab.org/) (27), RNA22 (https://www.rna-seqblog.com/rna22) (28) and TargetScan 7.1 (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71/) (29). PAK7-DEMs-miRNAs that appeared in at least five databases were selected for further investigation.

Based on the miRNA-lncRNA relations in both starBase (30) (version 2.0; http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) and InCeDB (31) (http://gyanxet-beta.com/lncedb/) databases, the DElncRNAs that were positively related with PAK7 were predicted, and PAK7-DElncRNA-miRNA associations were investigated. The RNAs with same miRNA-binding site were defined as ceRNAs. Based on the PAK7-DEM-miRNA and PAK7-DElncRNA-miRNA interactions, the lncRNA-mRNA relationships regulated by the same miRNA were investigated. miR2Disease database (http://watson.compbio.iupui.edu:8080/miR2Disease/index.jsp) was used for miRNA investigation (search keyword: ‘Glioblastoma multiforme’) followed by lncRNA-mRNA association analysis. The miRNA-lncRNA-mRNA regulation network was constructed using lncRNA-mRNA and DEM-DElncRNA relationships obtained. Finally, lncRNAs and mRNAs regulated by the same miRNA (PAK7 was also regulated by this miRNA) were screened as key ceRNAs for PAK7.

Survival analysis

To reveal the prognostic value of the hub genes in patients with GBM, survival analysis, including overall survival (OS) and OS status, was performed. The samples in the data were divided into a high expression group (up group) and low expression group (down group) according to the mean and median values of all lncRNAs/mRNAs in the ceRNA network. The survival package (version 2.41–3; http://cran.r-project.org/web/views/Survival.html) in R was used for the log-rank test (32) in two groups. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Associations between lncRNAs/mRNAs and GBM prognosis were analyzed. The Kaplan-Meier (KM) (33) survival curve was constructed based on these selected lncRNAs/mRNAs.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

A total of 8 tumor specimens were collected from patients with primary GBM (33–79 years old; 3 female and 5 male) who underwent neurosurgery at Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University from February 2017 to July 2018, and 8 normal brain specimen samples (44–83 years; 4 female and 4 male) were obtained from patients who underwent cerebral contusion at Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University from April 2017 to May 2018. Patients with a family history of cancer, and patients with chronic heart, lung, liver and kidney diseases were excluded. The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University and informed consent was obtained from all patients. RT-qPCR analysis was performed to detect the expression levels of several DElncRNAs (LINC00599) and DEMs [PAK7, PNMA family member 5 (PNMA5), and somatostatin receptor 1 (SSTR1)], as well as miR-185-5p. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from eight GBM samples and eight normal brain tissue samples using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Perfect Real Time) (Takara Biotechnology, Co., Ltd.). The amplification was performed SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (cat. no. DRR041A; Takara Bio, Inc.) under the following conditions on an ABI ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.): 50°C for 3 min, 95°C for 3 min, then 25 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec, followed by dissociation curve analysis (60°C-95°C; 0.5°C increments for 10 sec). The primers used are shown in Table I. Relative expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and calculated with the 2−ΔΔCq method (34), and each sample was assayed in triplicate.

Table I.

Primers used for RT-qPCR.

| Primer | Primer sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| PAK7-hF | GTAGTAGTTCCCCAGCGTGC |

| PAK7-hR | ACATGGTCTCAGAGGTCCAG |

| PNMA5-hF | TGCCCAGTCACATACCAGGAA |

| PNMA5-hR | CATACTTCGGCCCTCATCTTTC |

| SSTR1-hF | TGGCTATCCATTCCATTTGACC |

| SSTR1-hR | AGGACTGCATTGCTTGTCAGG |

| LINC00599-hF | CTAAACCCCTTGCCCCACAA |

| LINC00599-hR | AGGTTTTACAGGAGGGCAGC |

| hsa-miR-185-5p-R | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACTCAGGA |

| hsa-miR-185-5p-F | GGCTGGAGAGAAAGGCAGT |

| GAPDH-hF | TGACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG |

| GAPDH-hR | AGGCAGGGATGATGTTCTGGAGAG |

| U6-hF | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

| U6-hR | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

| human-U6-RT | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACAAAATATG |

| Downstream universal primer | GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT |

F, forward; R, reverse; RT, reverse transcription; qPCR, quantitative PCR; h, human; PAK7, p21 (RAC1) activated kinase 7; PNMA5, paraneoplastic antigen Ma family member 5; SSTR1, somatostatin receptor 1.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The difference between two groups was analyzed with a t-test, and a P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Investigation of DElncRNAs and DEMs

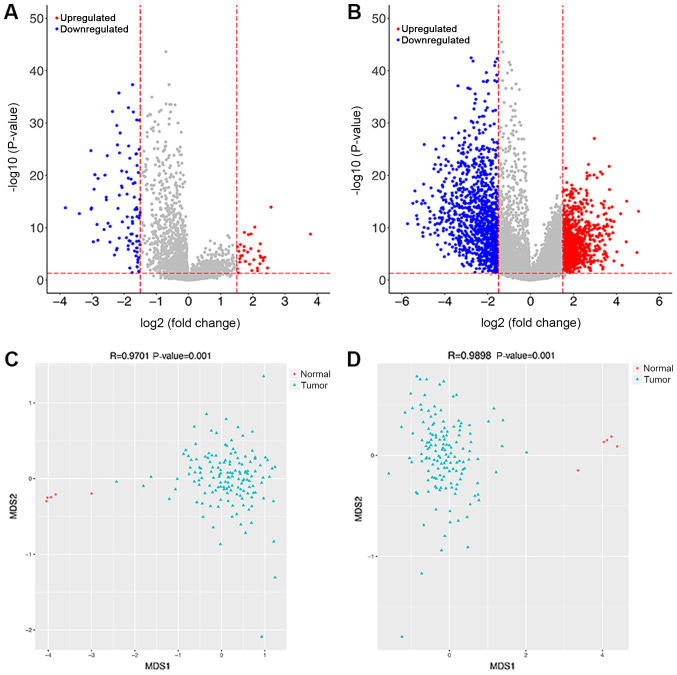

A total of 34 upregulated and 92 downregulated DElncRNAs were revealed between two groups. A total of 920 upregulated DEMs and 1,142 downregulated DEMs were observed. The volcanic diagrams for DElncRNAs and DEMs are shown in Fig. 1A and B. The expression values of DElncRNAs and DEMs were used to construct NMDS plots for these genes (Fig. 1C and D). The results showed that the green points (samples in GBM group) and red points (samples in control group) were distinctly separated, indicative of clear separation of samples based on the DEMs and DElncRNAs.

Figure 1.

Volcano plot and non-metric multidimensional scaling plot for the differentially expressed mRNAs and lncRNAs. (A) Volcano plot for differentially expressed lncRNAs. (B) Volcano plot for differentially expressed mRNAs. (C) Non-metric multidimensional scaling plot for differentially expressed lncRNAs. (D) Non-metric multidimensional scaling plot for differentially expressed mRNAs. For volcano plots, the red and blue points represent upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. For non-metric multidimensional scaling plots, the red and green points represent the samples from the normal group and tumor group, respectively. lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

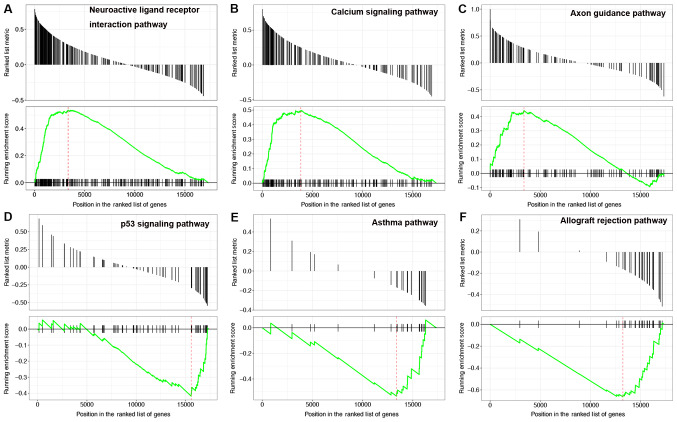

Pathway enrichment analysis

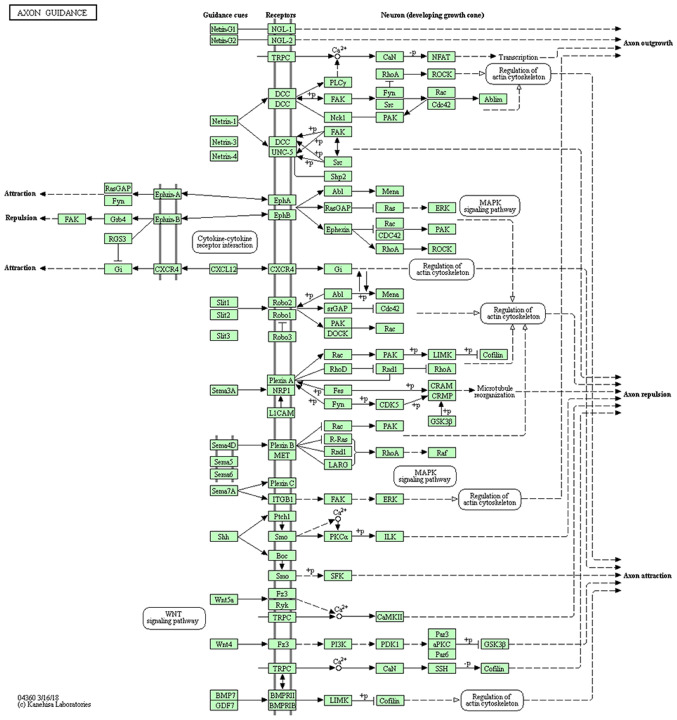

GSEA pathway analysis was performed on the mRNAs in mRNA-PAK7 pairs. The results showed that the upregulated mRNAs were mainly enriched in 14 pathways, including neuroactive ligand receptor interactions, calcium signaling pathways and axon guidance (Fig. 2A-C). The downregulated mRNAs were mainly enriched in 35 pathways, including p53 signaling pathways, asthma and allograft rejection (Fig. 2D-F). According to the P-value, the detailed information for the top six upregulated and downregulated pathways is shown in Table II. The results of the pathway analysis indicated that PKA7 participated in axon guidance pathway (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Results of gene set enrichment analysis for outstanding pathways enriched by the differentially expressed mRNAs. (A) Neuroactive ligand receptor interaction pathway. (B) Calcium signaling pathway. (C) Axon guidance pathway. (D) p53 signaling pathway. (E) Asthma pathway. (F) Allograft rejection pathway.

Table II.

Top 6 pathways enriched by up- and downregulated mRNAs.

| A, Upregulated mRNAs | ||

| Pathway ID | P-value (adjusted) | Enriched genes |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG_NEUROACTIVE_LIGAND_RECEPTOR_INTERACTION | 3.32×10−2 | GABRA3, CHRNA4, HRH3, CHRM1, GABRB3… |

| KEGG_CALCIUM_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 3.32×10−2 | CACNA1E, CHRM1, HTR6, PLCB1, GNAL… |

| KEGG_AXON_GUIDANCE | 3.32×10−2 | PAK1, PAK3, PAK6, PAK7, L1CAM… |

| B, Downregulated mRNAs | ||

| Pathway ID | P-value | Enriched genes |

| KEGG_NEUROACTIVE_LIGAND_RECEPTOR_INTERACTION | 3.32×10−2 | GABRA3, CHRNA4, HRH3, CHRM1, GABRB3… |

| KEGG_CALCIUM_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 3.32×10−2 | CACNA1E, CHRM1, HTR6, PLCB1, GNAL… |

| KEGG_AXON_GUIDANCE | 3.32×10−2 | PAK1, PAK3, PAK6, PAK7, L1CAM… |

Figure 3.

Schematic of the axon guidance pathway enriched by PAK7. Copyright for use of this image was granted.

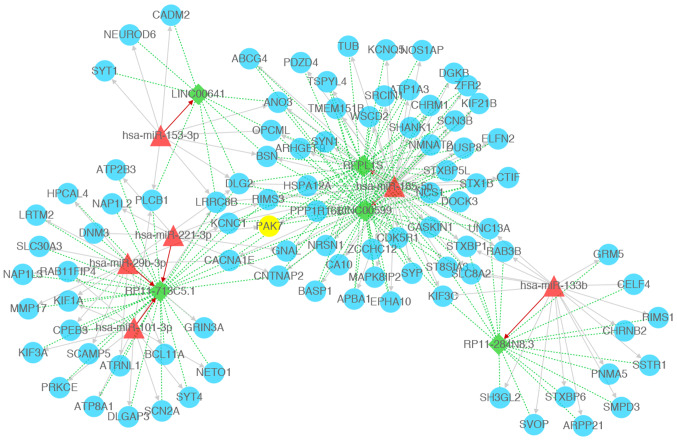

Co-expression network analysis

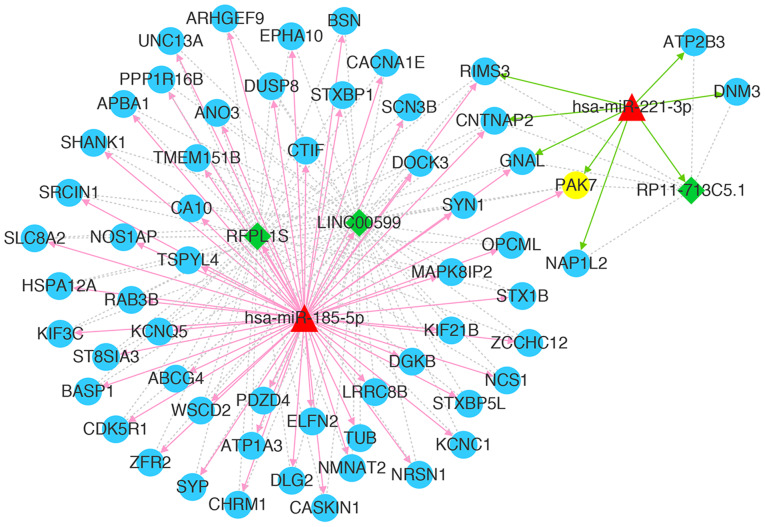

A total of 312 mRNAs and 22 lncRNAs showed positive correlation with PAK7. Following miRNA prediction, a total of 25,440 miRNA-lncRNA-mRNA regulatory interactions were reported from the screening of lncRNA-mRNA pairs regulated by the same miRNA. The selection of disease-related miRNAs revealed a total of 185 miRNA-lncRNA-mRNA relationships. Combined positive co-expression lncRNA-mRNA relationships revealed a total of 159 miRNA-lncRNA-mRNA regulatory associations. The ceRNA network was constructed based on network connectivity (Fig. 4). The results revealed 103 nodes (including 6 miRNAs, 92 mRNAs and 5 lncRNAs) and 281 interactions (including 115 miRNA-mRNA interactions, 7 miRNA-lncRNA interactions and 159 lncRNA-mRNA interactions), including miR-185-5p-LINC00599-PAK7 in the current ceRNA network.

Figure 4.

Competing endogenous RNA network constructed with miRNAs, lncRNAs, and mRNAs. Green diamonds represent lncRNAs, blue circles represents mRNAs (PAK7 is highlighted in yellow), red triangles represent miRNAs, red arrow represents miRNA-lncRNA regulatory relations, gray arrows represent miRNA-mRNA regulatory relations, green dotted lines represent mRNA-lncRNA co-expression relations. PAK7, p21 (RAC1)-activated kinase 7; miRNA/miR, microRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

The mRNAs and lncRNAs regulated by the same miRNAs as PAK7 were investigated, followed by the construction of a core ceRNA network. As shown in Fig. 5, a total of 63 nodes (2 miRNAs, 58 mRNAs and 3 lncRNAs) and 171 interactions (62 miRNA-mRNA relations, 3 miRNA-lncRNA relations and 106 lncRNA-mRNA relations) were observed in the current core ceRNA network. These mRNAs and lncRNAs were regulated by hsa-mir-185-5p or hsa-mir-221-3p together with PAK7.

Figure 5.

Core competing endogenous RNA network associated with PAK7. Green diamonds represent lncRNAs, blue circles represent mRNAs (PAK7 is highlighted in yellow), red triangles represent miRNAs, red arrows represent miRNA-lncRNA regulatory relations, gray lines represent miRNA-mRNA regulatory relations, green dotted lines represent mRNA-lncRNA co-expression relations, red arrows represent relations with hsa-miR-185-5p, green arrows represent relations with hsa-miR-221-3p. PAK7, p21 (RAC1)-activated kinase 7; miRNA/miR, microRNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

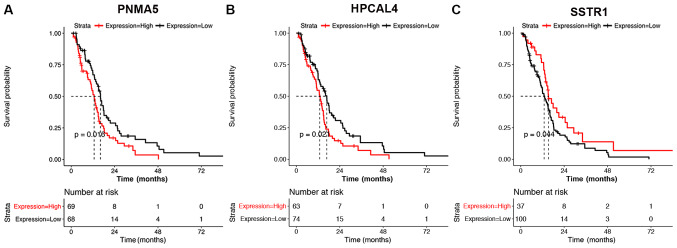

Survival analysis for core ceRNAs

A total of 143 samples with OS prognosis information, and mRNA and lncRNA data were explored. PNMA5 was a unique mRNA associated with OS prognosis upon grouping of all mRNAs/lncRNAs based on the median values of expression (Fig. 6A). Hippocalcin-like 4 and SSTR1 were two outstanding mRNAs associated with OS prognosis following grouping of all mRNAs/lncRNAs based on the mean value of expression (Fig. 6B and C). KM analysis showed that PNMA5, Hippocalcin-like 4 and SSTR1 may be the factors associated with prognosis in patients with GBM.

Figure 6.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis of the mRNAs potentially associated with glioblastoma multiforme prognosis. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for PNMA5. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for HPCAL4. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for SSTR1. PNMA5, paraneoplastic antigen Ma family member 5; HPCAL4, hippocalcin-like 4; SSTR1, somatostatin receptor 1.

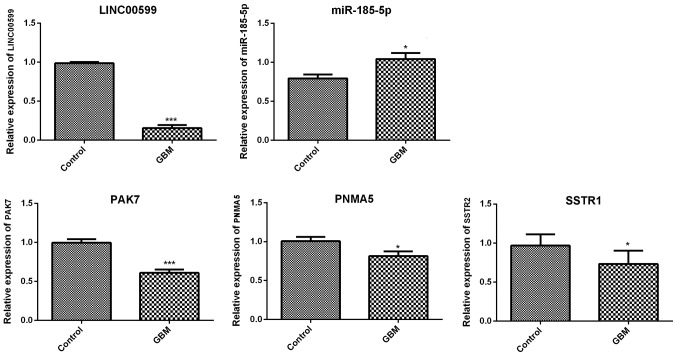

RT-qPCR validation

The results of RT-qPCR showed that the mRNA levels of PAK7 and SSTR1 were significantly downregulated in GBM samples compared with control samples. Furthermore, LINC00599 expression was downregulated and miR-185-5p expression was upregulated in GBM samples (Fig. 7). These results were consistent with the bioinformatics analysis results. However, contrary to the bioinformatics analysis results, the mRNA expression of PNMA5 was significantly downregulated in GBM samples compared with control samples.

Figure 7.

Relative expression levels of GBM-associated RNAs. LINC00599, PAK7, PNMA5, SSTR1 and miR-185-5p were analyzed in GBM and control tissue samples. miR-185-5p, microRNA-185-5p; PAK7, p21 (RAC1)-activated kinase 7; PNMA5, paraneoplastic antigen Ma family member 5; SSTR1, somatostatin receptor 1. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Discussion

GBM is the most common malignant brain tumor in adults (35). Targeted gene therapy such as PAK7 serves as a therapeutic strategy for glioma (11). However, the detailed mechanisms underlying the effects of PAK7 expression on GBM progression remain incompletely understood. In the present study, gene expression data of GBM were downloaded and reanalyzed using bioinformatic tools. The results revealed a total of 954 upregulated and 1,234 downregulated DEGs between GBM and control samples. These DEGs, including PAK7, were mainly enriched in pathways such as axon guidance. ceRNA network analysis revealed several outstanding ceRNA relationships, including miR-185-5p-LINC00599-PAK7. Moreover, PNMA5 and SSTR1 were two outstanding prognostic genes associated with OS in survival analysis.

Bioinformatic approaches have been widely used for the identification of genes that are associated with GBM. Wei et al (36) identified DEGs regulated by transcription factors in GBM by analyzing the GSE4290 dataset downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Zhang et al (37) selected GSE50161 from GEO database to identify potential oncogenes associated with GBM progression. Moreover, Liu et al (38) analyzed the glioma gene expression profile dataset GSE4290 for the identification of DEGs. These studies were performed based on datasets downloaded from GEO database. In particular, the expression profile data in GEO usually lack clinical data and may be unsuitable for survival analysis. In the present study, a dataset obtained from TCGA database that included clinical data was used, permitting survival analysis. In addition to DEM selection, the potential lncRNAs were also selected, and a regulatory network was constructed to explore the potential molecular mechanism of GBM.

Axon guidance (also called axon pathfinding) is a subfield of neural development related to the process by which neurons send out axons to reach the correct targets (39). Agrawal et al (40) reported the development of acute axonal polyneuropathy after the resection of GBM, indicative of the close relationship between axon guidance and GBM. Axon guidance is accomplished with the involvement of relatively few guidance molecules (41). Certain guidance molecules, such as PLEXIN-B2, may promote the tumorigenesis of GBM through axon guidance pathways (42). The dysregulation in gene expression implicated in the canonical axon guidance pathway influences the glioma cell cycle (43). Furthermore, PAK family members, including PAK1, PAK4 and PAK6, commonly participate in tumorigenesis as guide molecules (44–46). Hing et al (47) demonstrated that PAK was not only a critical regulator of axon guidance, but also served as a downstream effector of Dock in vivo. Axon guidance was shown to be involved in the PAK-small GTPase signaling in patients with schizophrenia (48). In the present study, PAK7 was one of the most outstanding DEGs enriched in axon guidance pathway. Thus, we speculate that PAK7 may participate in the tumorigenesis of GBM via the axon guidance pathway.

Studies have shown that miRNAs may suppress the process of tumorigenesis through the induction of cell differentiation and cycle arrest (49). It was shown that the negative expression of miR-185 in GBM may inhibit the proliferation of glioma cell lines (50). Thus, miR-185 is commonly used as a predictive biomarker for the prognosis of malignant glioma (51,52). miRNAs play important roles in tumor progression by targeting lncRNAs (53). Tran et al (54) reported that lncRNAs such as LINC00176 may regulate cell cycle and survival by titrating the tumor suppressor miR-185. Despite miRNA-lncRNA interactions, the lncRNA-mRNA regulatory relations are also vital for tumor progression (55). A comprehensive analysis on the functional miRNA-mRNA regulatory network revealed the association of miRNA signatures with glioma (56). As an mRNA, PAK7 is related with tumor progression by targeting of miRNAs, including miR-492 (57). Pan et al (58) showed that miR-106a-5p inhibited the migration and invasion of renal cell carcinoma cells by targeting PAK7. Neuronal activity regulates spine formation, at least in part, by increasing miRNA transcription, which in turn activates PAK actin remodeling pathway (59). However, the association between miR-185-PAK7 interactions and GBM progression is unclear. In the present study, ceRNA network analysis showed that the miR-185-5p-LINC00599-PAK7 axis was one of the regulatory relationships most strongly associated with GBM. Thus, it is hypothesized that the miR-185-5p may play an important role in GBM progression by sponging the PAK7-LINC00599 interaction.

The members of the PNMA family have been identified as onconeuronal antigens that are aberrantly expressed on cancer cells (60). Distinct functional domains of PNMA5 mediate protein-protein interactions, nuclear localization and apoptosis signaling in human cancer cells (60). As a novel tumor-associated gene, PNMA5 plays an important role in maintaining the malignant phenotype of hepatocellular carcinoma (61). However, studies on PNMA5 expression in glioma or GBM are very rare. SSTR1 acts at several sites to inhibit the release of hormones or secretory proteins (62). Kiviniemi et al (63) indicated that SSTR2 may serve as a prognostic marker in high-grade glioma. The activation of SSTR1 was shown to induce glioma growth arrest in vitro and in vivo (64). However, whether SSTR1 can be used as a prognostic marker in GBM is unclear. In the present study, the survival analysis results showed that PNMA5 and SSTR1 were the two most notable DEGs associated with overall survival in disease. This result indicated that PNMA5 and SSTR1 may be used as novel prognostic markers for GBM. However, certain limitations of this study include the small sample size and lack of verification. Thus, a larger sample size with more extensive verification analysis is warranted in future investigations.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that PAK7 expression was downregulated in GBM, and that this gene may participate in the tumorigenesis of GBM through the ceRNA pathway of miR-185-5p-LINC00599-PAK7. Although the expression levels of miR-185-5p, LINC00599 and PAK7 in GBM tissue were detected, the regulatory relation of this ceRNA needs to be validated in future studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Torch Research Fund From The Fourth Affiliated Hospital Of Harbin Medical University (grant no. HYDSYHJ201902).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

XW was involved in the conception and design of the research, participated in the acquisition of data and drafted the manuscript. SL performed analysis and interpretation of data. ZS performed analysis. PZ conceived the study, participated in its design and co-ordination, and aided in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of The Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University and Heilongjiang Provincial Hospital. Informed consent was provided by all patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, Stroup NE, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(Suppl 2):ii1–ii56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young RM, Jamshidi A, Davis G, Sherman JH. Current trends in the surgical management and treatment of adult glioblastoma. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:121. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.05.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nam JY, de Groot JF. Treatment of glioblastoma. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:629–638. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallego O. Nonsurgical treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Curr Oncol. 2015;22:e273–e281. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bo LJ, Wei B, Li ZH, Wang ZF, Gao Z, Miao Z. Bioinformatics analysis of miRNA expression profile between primary and recurrent glioblastoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:3579–3586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo Q, Zhang M, Hu G, Dai Y, Liu D, Yu S. Bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed genes in glioblastoma. Acta Med Univ Sci Technol Huazhong. 2018;((Issue 1)):38–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu X, Wang C, Wang X, Ma G, Li Y, Cui L, Chen Y, Zhao B, Li K. Efficient inhibition of human glioma development by RNA interference-mediated silencing of PAK5. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11:230–237. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.9193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rane CK, Minden A. P21 activated kinases: Structure, regulation, and functions. Small GTPases. 2014;5(pii):e28003. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.28003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dan C, Nath N, Liberto M, Minden A. PAK5, a new brain-specific kinase, promotes neurite outgrowth in N1E-115 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:567–577. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.567-577.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey A, Dan I, Kristiansen TZ, Watanabe NM, Voldby J, Kajikawa E, Khosravi-Far R, Blagoev B, Mann M. Cloning and characterization of PAK5, a novel member of mammalianp21-activated kinase-II subfamily that is predominantly expressed in brain. Oncogene. 2002;21:3939–3948. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han ZX, Wang XX, Zhang SN, Wu JX, Qian HY, Wen YY, Tian H, Pei DS, Zheng JN. Downregulation of PAK5 inhibits glioma cell migration and invasion potentially through the PAK5-Egr1-MMP2 signaling pathway. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2014;31:234–241. doi: 10.1007/s10014-013-0161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhai J, Qu S, Li X, Zhong J, Chen X, Qu Z, Wu D. miR-129 suppresses tumor cell growth and invasion by targeting PAK5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;464:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, Tapanari E, Diekhans M, Kokocinski F, Aken BL, Barrell D, Zadissa A, Searle S, et al. GENCODE: The reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE project. Genome Res. 2012;22:1760–1774. doi: 10.1101/gr.135350.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quadrianto N, Buntine WL. Encyclopedia of Machine Learning. Springer; Boston, MA: 2016. Linear regression. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koop G. Bayesian methods for empirical macroeconomics with big data. Rev Econ Anal. 2017;9:33–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smyth GK. Statistics for Biology and Health, corp-author. Limma: Linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, Carey VJ, Huber W, Irizarry RA, Dudoit S, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Springer; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 397–420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yekti YND and Yassierli: Kansei engineering using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) and cluster analysis methods. Seanes International Conference on Human Factors and Ergonomics in South-East Asia. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oksanen J, Blanchet F, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin R, O'Hara R, Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, et al. vegan: Community ecology package version 2.0–10. J Stat Softw. 2013;48:103–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark KR. Non-parametric multivariate analysis of changes in community structure. Aust J Ecol. 1993;18:117–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Morishima K, Tanabe M. New approach for understanding genome variations in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D590–D595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breuer K, Foroushani AK, Laird MR, Chen C, Sribnaia A, Lo R, Winsor GL, Hancock RE, Brinkman FS, Lynn DJ. InnateDB: Systems biology of innate immunity and beyond-recent updates and continuing curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41((Database Issue)):D1228–D1233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dweep H, Gretz N. miRWalk2.0: A comprehensive atlas of microRNA-target interactions. Nat Methods. 2015;12:697. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno R, Miranda DR, Fidler V, Van SR. Evaluation of two outcome prediction models on an independent database. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:50–61. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199801000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X. miRDB: A microRNA target prediction and functional annotation database with a wiki interface. RNA. 2008;14:1012–1017. doi: 10.1261/rna.965408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vejnar CE, Zdobnov EM. MiRmap: Comprehensive prediction of microRNA target repression strength. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11673–11683. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miranda K, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam WL, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126:1203–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: Determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu LH, Yang JH. starBase v2.0: Decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42((Database Issue)):D92–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das S, Ghosal S, Sen R, Chakrabarti J. lnCeDB: Database of human long noncoding RNA acting as competing endogenous RNA. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alberti C, Timsit JF, Chevret S. Survival analysis-the log rank test. Rev Mal Respir. 2005;22:829–832. doi: 10.1016/S0761-8425(05)85644-X. (In French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bland JM, Altman DG. Survival probabilities (the Kaplan-Meier method) BMJ. 1998;317:1572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ni Y, Zhang F, An M, Yin W, Gao Y. Early candidate biomarkers found from urine of glioblastoma multiforme rat before changes in MRI. Sci China Life Sci. 2018;61:982–987. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei B, Wang L, Du C, Hu G, Wang L, Jin Y, Kong D. Identification of differentially expressed genes regulated by transcription factors in glioblastomas by bioinformatics analysis. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:2548–2554. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Xia Q, Lin J. Identification of the potential oncogenes in glioblastoma based on bioinformatic analysis and elucidation of the underlying mechanisms. Oncol Rep. 2018;40:715–725. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu M, Xu Z, Du Z, Wu B, Jin T, Xu K, Xu L, Li E, Xu H. The identification of key genes and pathways in glioma by bioinformatics analysis. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:1278081. doi: 10.1155/2017/1278081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suter TACS, DeLoughery ZJ, Jaworski A. Meninges-derived cues control axon guidance. Dev Biol. 2017;430:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agrawal R, Chugh C, Mukherji JD, Singh P. Acute axonal polyneuropathy following resection of a glioblastoma multiforme. Neurol India. 2017;65:1422–1423. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.217951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pace KR, Dutt R, Galileo DS. Exosomal L1CAM stimulates glioblastoma cell motility, proliferation, and invasiveness. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(pii):E3982. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Y, Tejero-Villalba R, Kesari S, Zou H, Friedel R. ANGI-19. The axon guidance receptor Plexin-B2 promotes tumorigenicity of glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(Suppl 6):vi25. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox168.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunapuli P, Lo K, Hawthorn L, Cowell JK. Reexpression of LGI1 in glioma cells results in dysregulation of genes implicated in the canonical axon guidance pathway. Genomics. 2010;95:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang G, Song Y, Liu T, Wang C, Zhang Q, Liu F, Cai X, Miao Z, Xu H, Xu H, et al. PAK1-mediated MORC2 phosphorylation promotes gastric tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9877–9886. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He LF, Xu HW, Chen M, Xian ZR, Wen XF, Chen MN, Du CW, Huang WH, Wu JD, Zhang GJ. Activated-PAK4 predicts worse prognosis in breast cancer and promotes tumorigenesis through activation of PI3K/AKT signaling. Oncotarget. 2016;8:17573–17585. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts JA. Diss Theses Gradworks; 2012. An investigation of the role of PAK6 in tumorigenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hing H, Xiao J, Harden N, Lim L, Zipursky SL. Pak functions downstream of Dock to regulate photoreceptor axon guidance in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;97:853–863. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80798-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen SY, Huang PH, Cheng HJ. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1-mediated axon guidance involves TRIO-RAC-PAK small GTPase pathway signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5861–5866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018128108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Z, Ma X, Sung D, Li M, Kosti A, Lin G, Chen Y, Pertsemlidis A, Hsiao TH, Du L. microRNA-449a functions as a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma through inducing cell differentiation and cell cycle arrest. RNA Biol. 2015;12:538–554. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1023495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrow C, Smirnov I, Adai A, Yeh RF, Mistra A, Feuerstein B. MIR-185 is lost in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and inhibits proliferation in glioma cell lines. Meet Soc Neuro Oncol. 2008:767. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang H, Liu Q, Liu X, Ye F, Xie X, Xie X, Wu M. Plasma miR-185 as a predictive biomarker for prognosis of malignant glioma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:630–634. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.146121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang H, Wang Z, Liu X, Liu Q, Xu G, Li G, Wu M. LRRC4 inhibits glioma cell growth and invasion through a miR-185-dependent pathway. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12:1032–1042. doi: 10.2174/156800912803251180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paraskevopoulou MD, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Analyzing MiRNA-LncRNA interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1402:271–286. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3378-5_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tran DDH, Kessler C, Niehus SE, Mahnkopf M, Koch A, Tamura T. Myc target gene, long intergenic noncoding RNA, Linc00176 in hepatocellular carcinoma regulates cell cycle and cell survival by titrating tumor suppressor microRNAs. Oncogene. 2018;37:75–85. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amirkhah R, Schmitz U, Linnebacher M, Wolkenhauer O, Farazmand A. MicroRNA-mRNA interactions in colorectal cancer and their role in tumor progression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2015;54:129–141. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Xu J, Chen H, Bai J, Li S, Zhao Z, Shao T, Jiang T, Ren H, Kang C, Li X. Comprehensive analysis of the functional microRNA-mRNA regulatory network identifies miRNA signatures associated with glioma malignant progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song X, Xie Y, Liu Y, Shao M, Yang W. MicroRNA-492 overexpression exerts suppressive effects on the progression of osteosarcoma by targeting PAK7. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40:891–897. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pan YJ, Wei LL, Wu XJ, Huo FC, Mou J, Pei DS. MiR-106a-5p inhibits the cell migration and invasion of renal cell carcinoma through targeting PAK5. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3155. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Impey S, Davare M, Lasiek A, Fortin D, Ando H, Varlamova O, Obrietan K, Soderling TR, Goodman RH, Wayman GA. An activity-induced microRNA controls dendritic spine formation by regulating Rac1-PAK signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;43:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee YH, Pang SW, Poh CL, Tan KO. Distinct functional domains of PNMA5 mediate protein-protein interaction, nuclear localization, and apoptosis signaling in human cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1967–1977. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2205-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teng XM, Deng Q, Han ZG, Huang J. Expression of PNMA5 in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues and its function. Tumor. 2008;28:911–915. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bruns C, Weckbecker G, Raulf F, Kaupmann K, Schoeffter P, Hoyer D, Lübbert H. Molecular pharmacology of somatostatin receptor subtypes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;733:138–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb17263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiviniemi A, Gardberg M, Frantzén J, Pesola M, Vuorinen V, Parkkola R, Tolvanen T, Suilamo S, Johansson J, Luoto P, et al. Somatostatin receptor subtype 2 in high-grade gliomas: PET/CT with (68)Ga-DOTA-peptides, correlation to prognostic markers, and implications for targeted radiotherapy. EJNMMI Res. 2015;5:25. doi: 10.1186/s13550-015-0106-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gatti M, Pattarozzi A, Würth R, Barbieri F, Florio T. Somatostatin and somatostatin receptors 1, 2 and 5 selective agonists inhibit C6 glioma cell growth in vitro and in vivo: Analysis of activated intracellular pathways. Regulat Peptides. 2010;164:38. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.07.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.