Abstract

Bioorthogonal catalysis offers a unique strategy to modulate biological processes through the in situ generation of therapeutic agents. However, the direct application of bioorthogonal transition metal catalysts (TMCs) in complex media poses numerous challenges due to issues of limited biocompatibility, poor water solubility, and catalyst deactivation in biological environments. We report here the creation of catalytic “polyzymes”, comprised of self-assembled polymer nanoparticles engineered to encapsulate lipophilic TMCs. The incorporation of catalysts into these nanoparticle scaffolds creates water-soluble constructs that provide a protective environment for the catalyst. The potential therapeutic utility of these nanozymes was demonstrated through antimicrobial studies in which a cationic nanozyme was able to penetrate into biofilms and eradicate embedded bacteria through the bioorthogonal activation of a pro-antibiotic.

Keywords: Bioorthogonal chemistry, Transition Metal Catalysts (TMCs), nanozymes, polymer nanoparticles, biofilms

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Introduction

Bioorthogonal chemistry has emerged as a promising strategy for modulating bioprocesses using reactions that cannot be performed by natural enzymes.1–5 Bioorthogonal unmasking reactions mediated by transition metal catalysts (TMCs) present a powerful tool for biomedical applications arising from their ability to generate therapeutic agents in situ, minimizing off-target effects.6–15 In this prodrug strategy, a drug is first modified with a masking group, rendering it inactive (i.e., a prodrug); TMCs then remove the protecting group at the targeted location to restore activity, providing on-site therapeutic action. However, the direct application of TMC-mediated reactions in biological environment is challenging due to their limited water solubility and biocompatibility.16

The incorporation of TMCs into nanomaterial hosts solubilizes and stabilizes hydrophobic catalyst molecules while preserving catalytic activity and stability in complex biological media.16–23 In addition, nanomaterial scaffolds can be engineered to localize within therapeutically important targets, such as bacterial biofilms, tissues and cellular environments, providing a targeting strategy for bioorthogonal activation of prodrugs.24–34

Bacterial biofilms are important potential targets for biorthogonal therapeutics as their formation results in persistent infections on wounds and indwelling medical devices, including urinary catheters, arthro-prostheses and dental implants.35–37 Biofilms are aggregates of micro-organisms in which bacterial cells are embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS).38,39 This polymeric matrix provides protection to bacterial cells and severely hinders the penetration of most hydrophobic molecules, making treatment particularly challenging.40,41

Here, we report a self-assembled polymeric nanoparticle that encapsulates TMCs into a hydrophobic pocket, providing a bioorthogonal “polyzyme”. We hypothesized that beyond solubilizing and stabilizing the catalyst molecules, the cationic nanoparticle would act as a vehicle to facilitate the penetration of TMCs into biofilms.42–44 To this end, we synthesized a quaternary ammonium polymer possessing hydrophobic alkyl side chains (Figure 1a). This polymer self-assembles into nanoparticles, encapsulating TMCs within a protective hydrophobic environment. Moreover, the cationic nature of the polymer facilitates penetration of the particle into biofilms. The penetration ability of our polyzyme was demonstrated by performing in vitro activation of the non-fluorescent pro-dye (Figure 1a) using either polyzyme or free catalyst molecules. Biofilms treated with polyzyme exhibited bright fluorescence whereas biofilms incubated with free catalyst molecule showed negligible activation. The penetration ability of the polyzymes was further evidenced by monitoring a fluorescent metal-free analog. The therapeutic potential of the bioorthogonal polyzyme platform was demonstrated through the activation of a pro-antibiotic to effectively eradicate bacterial biofilms.

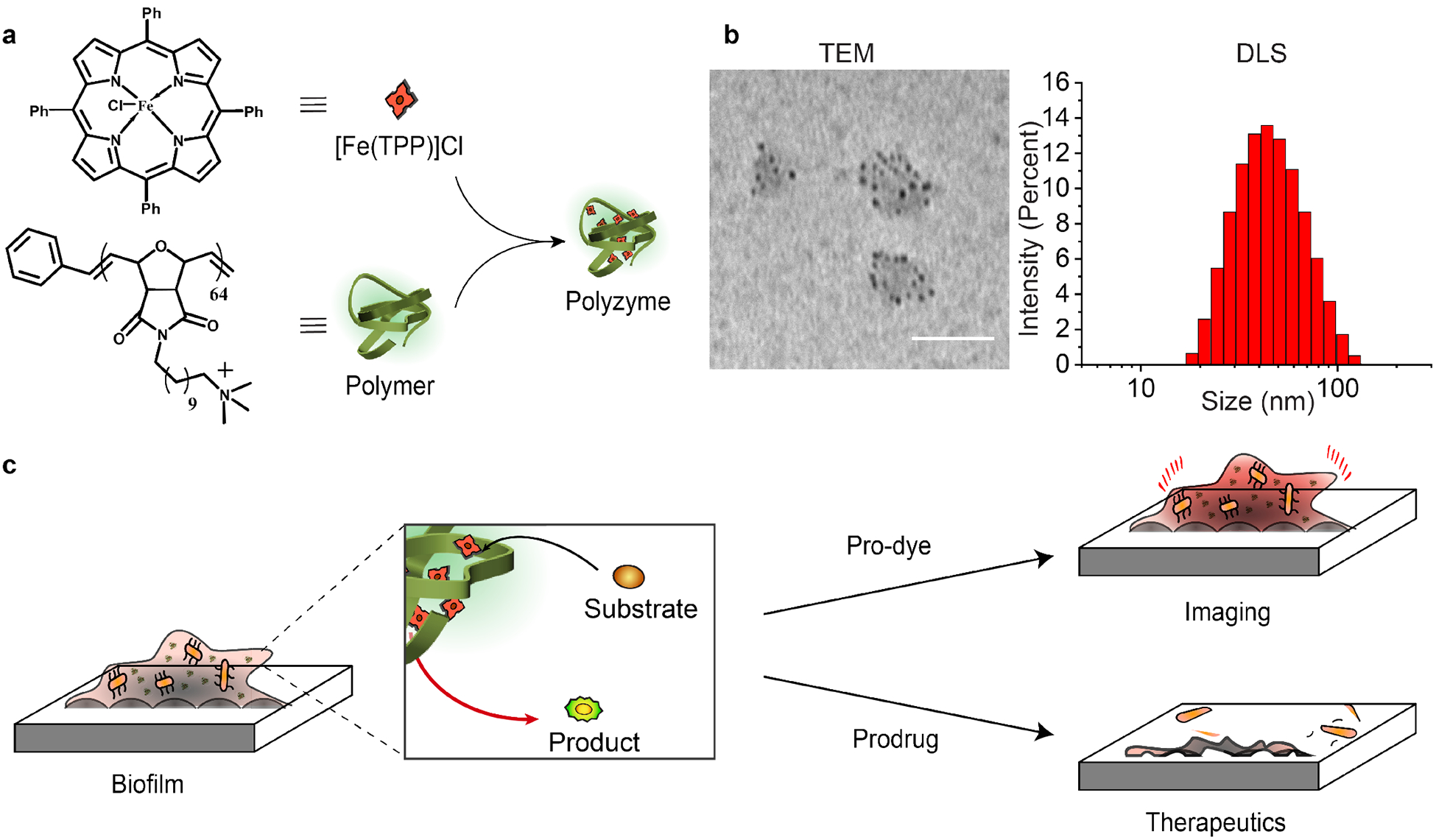

Figure 1.

a) Structures of [Fe(TPP)]Cl and polymeric nanoparticle. b) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging and dynamic light scattering measurement (DLS). Scale bar is 100 nm. c) Schematic representation of the bioorthogonal activation for imaging and therapeutics.

Results and Discussion

Design and synthesis of the polyzyme.

The polyzyme features two main components: a self-assembled polymer nanoparticle and the encapsulated transition metal catalyst (TMC). The hosting polymer was designed with monomers featuring two crucial components: i) an alkyl chain that fosters formation of a self-assembled nanoparticle to provide a hydrophobic inner shell to encapsulate and protect TMCs, and ii) a cationic terminal groups for maintaining water solubility and penetrating the biofilm.16 For the polymer, we chose a quaternary ammonium poly(oxanorborneneimide) containing a C11-bridged alkyl chain that we have previously shown can penetrate into biofilms.44

We chose 5,10,15,20-tetraphenyl-21H,23H-porphine (TPP)-containing complex, [Fe(TPP)]Cl as the catalyst due to its high catalytic efficiency (Figure 1a).45 This iron-based complex catalyzes the reduction of aryl azides to their respective amines (Figure 2a) in the presence of biogenic thiols. In this catalytic cycle, we used glutathione (GSH) as the reducing agent to convert intermediate FeIV-nitrene to the reduced amine.46

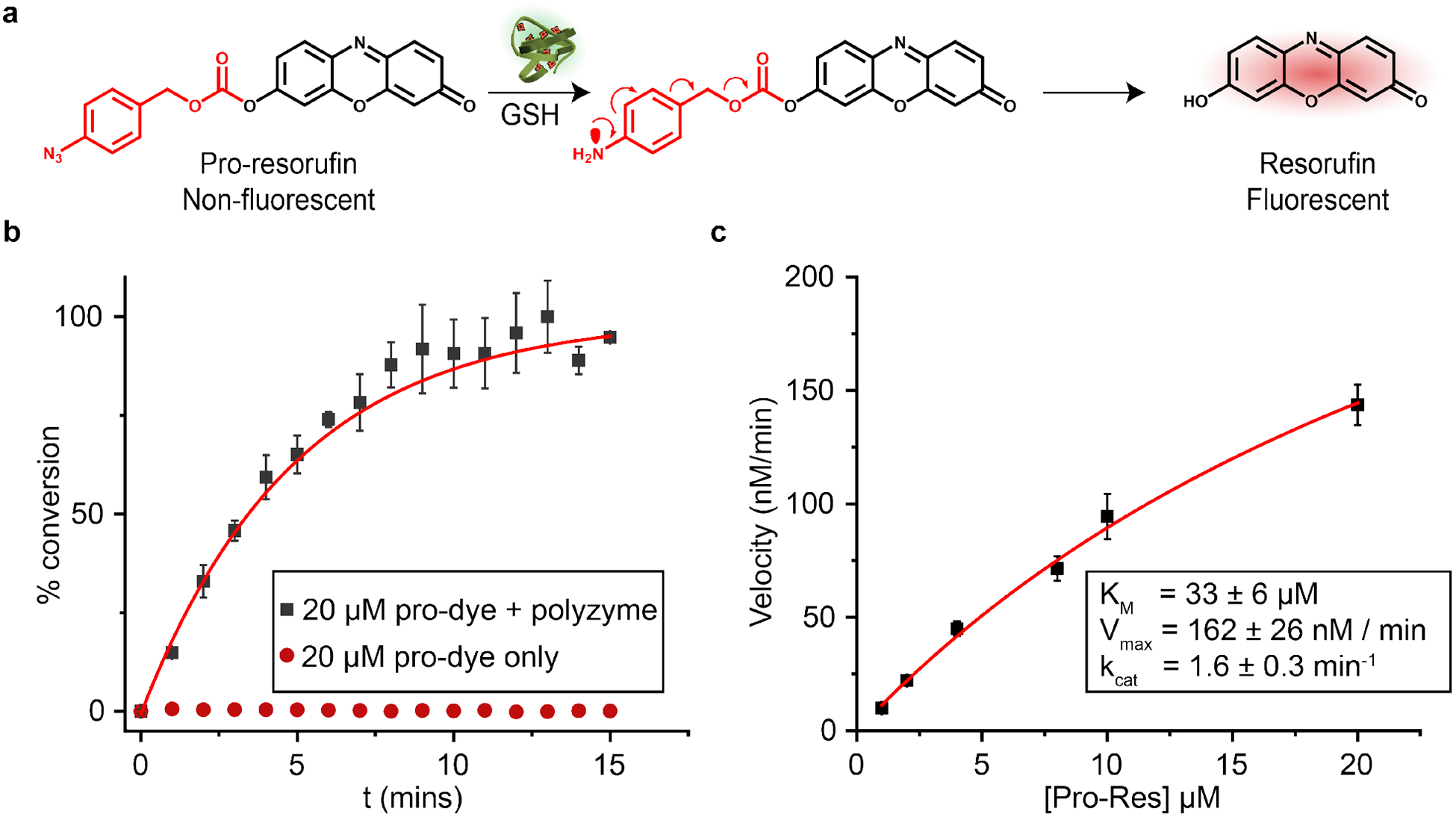

Figure 2.

a) Schematic representation of the bioorthogonal activation of aryl azide-protected resorufin. b) Catalytic activity of polyzyme (100 nM) was tracked by measuring changes in fluorescence (Ex. 570nm, Em. 590nm) of pro-resorufin solutions at different concentrations. The curve is fit with a non-linear exponential equation. 1 mM GSH was used as the cofactor. c) Polyzyme kinetics is shown as a function of substrate concentration; line is the regression curve corresponding to Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

To fabricate the polyzyme (Figure 1a), the polymer was dissolved in water while [Fe(TPP)]Cl was dissolved in equal volume of THF. The solutions were mixed, and then stirred overnight to allow the encapsulation of the catalyst into the hydrophobic pockets of polymeric nanoparticles. Next, the sample was dried under flowing nitrogen, and then redissolved in water. The polyzyme solution was subsequently filtered 5 times to remove the precipitated catalyst and dialyzed against water to remove any unbound catalyst. Dynamic light scattering (DLS, Figure 1b) measurements on the polyzymes showed the formation of ~50 nm nanocatalysts with no aggregation observed after the encapsulation of [Fe(TPP)]Cl (Nanozyme PDI = 0.147). The particle structure was also confirmed by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As shown in Figure 1b, the [Fe(TPP)]Cl (black dots) readily self-assembled through stacking and were encapsulated into polymer nanoparticles. The amount of [Fe(TPP)]Cl encapsulated in polymer nanoparticles was determined quantitively using UV-Vis (0.59 mg per mg of polyzyme, Figure S2, Supporting Information).

Catalytic efficacy of polyzymes in solution.

Nanozyme activity was quantified through activation of a resorufin-based pro-fluorophore (Pro-Res, Figure 2a). This pro-dye was masked with an aryl azide carbonate unit bound to the phenolate of resorufin to render it non-fluorescent. The catalytic reduction of azide group mediated by [Fe(TPP)]Cl results in fragmentation, releasing the fluorescent resorufin molecule.47,48 The fluorogenesis of this dye provides a direct way for studying catalytic kinetics.

Resorufin fluorescence was monitored in M9 media at 37 °C to quantify the catalytic properties of the polyzyme (Figure 2b). Fluorescence increased immediately after mixing the substrate and polyzyme (100 nM), with no significant change in fluorescence observed for the pro-dye only. Polyzyme activity followed a standard Michaelis-Menten kinetic model (Figure 2c), allowing facile quantification of the catalytic process.

Penetration of polyzymes into biofilms.

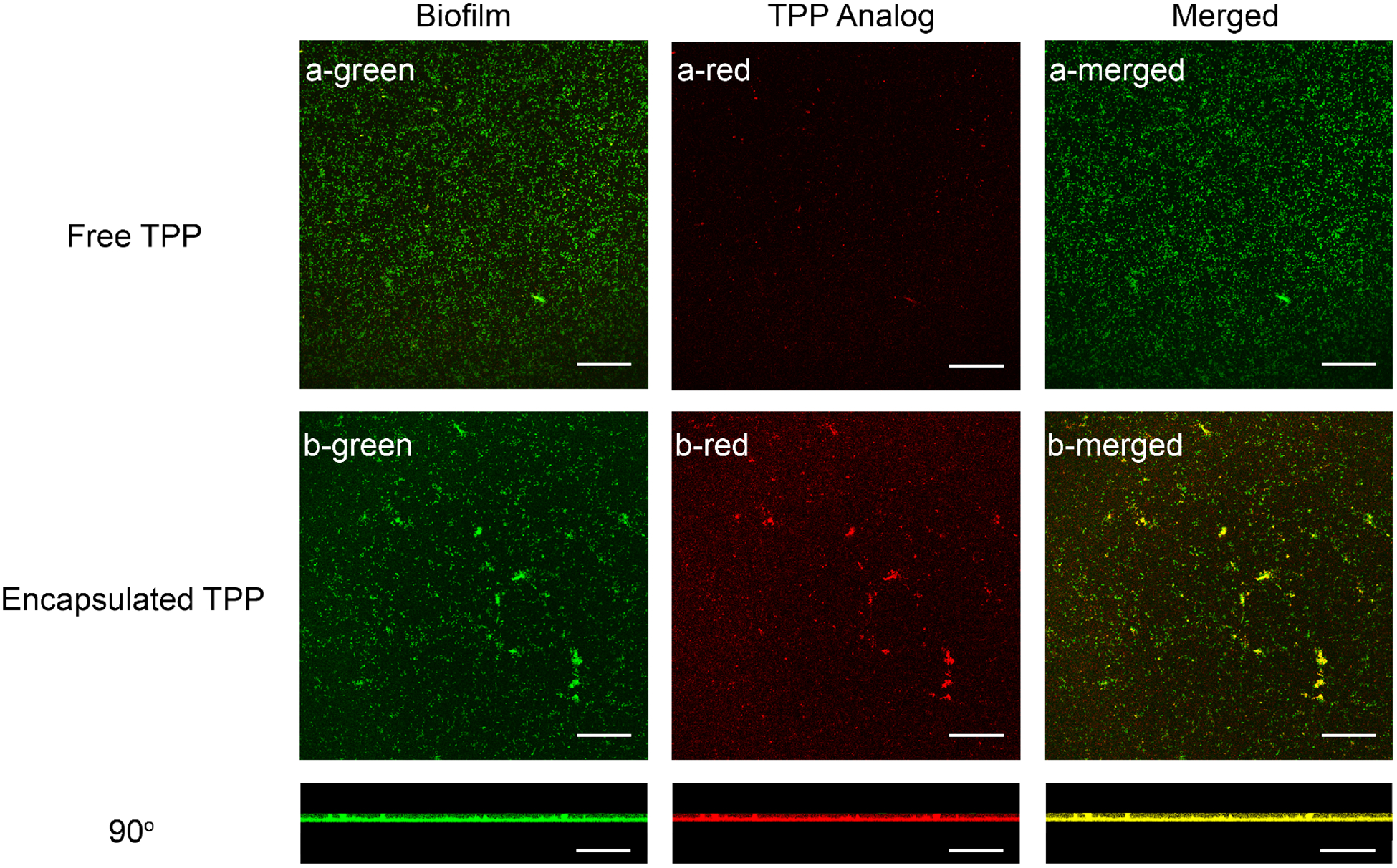

Having characterized the catalytic activity of the polyzyme in solution, we next probed bioorthogonal catalysis in biofilms. As the ability of the catalyst to accumulate inside of biofilms is crucial for in situ activation, the penetration ability of polyzymes was determined using confocal microscopy. To monitor the non-fluorescent [Fe(TPP)]Cl, we replaced the encapsulated catalyst with the metal-free analog, tetraphenyl porphyrin, TPP, which has red fluorescence. A GFP (green fluorescent protein) - expressing E. coli biofilm was chosen to facilitate microscopy and the biofilm formation was confirmed by staining assay using crystal violet (Figure S7, Supporting Information). Biofilms were incubated with polyzyme analog and free TPP for 1 hr in M9 media and then washed with PBS buffer three times. The experiment showed that encapsulated TPP readily penetrated biofilms whereas free porphyrin had significant difficulty in penetration (Figure 3). This indicates that polymer-based nanometric scaffolds act as a vehicle to facilitate the penetration of the hydrophobic TMCs into biofilms (Quantitative enhancement of fluorescence intensity is in Figure S4, Supporting Information).

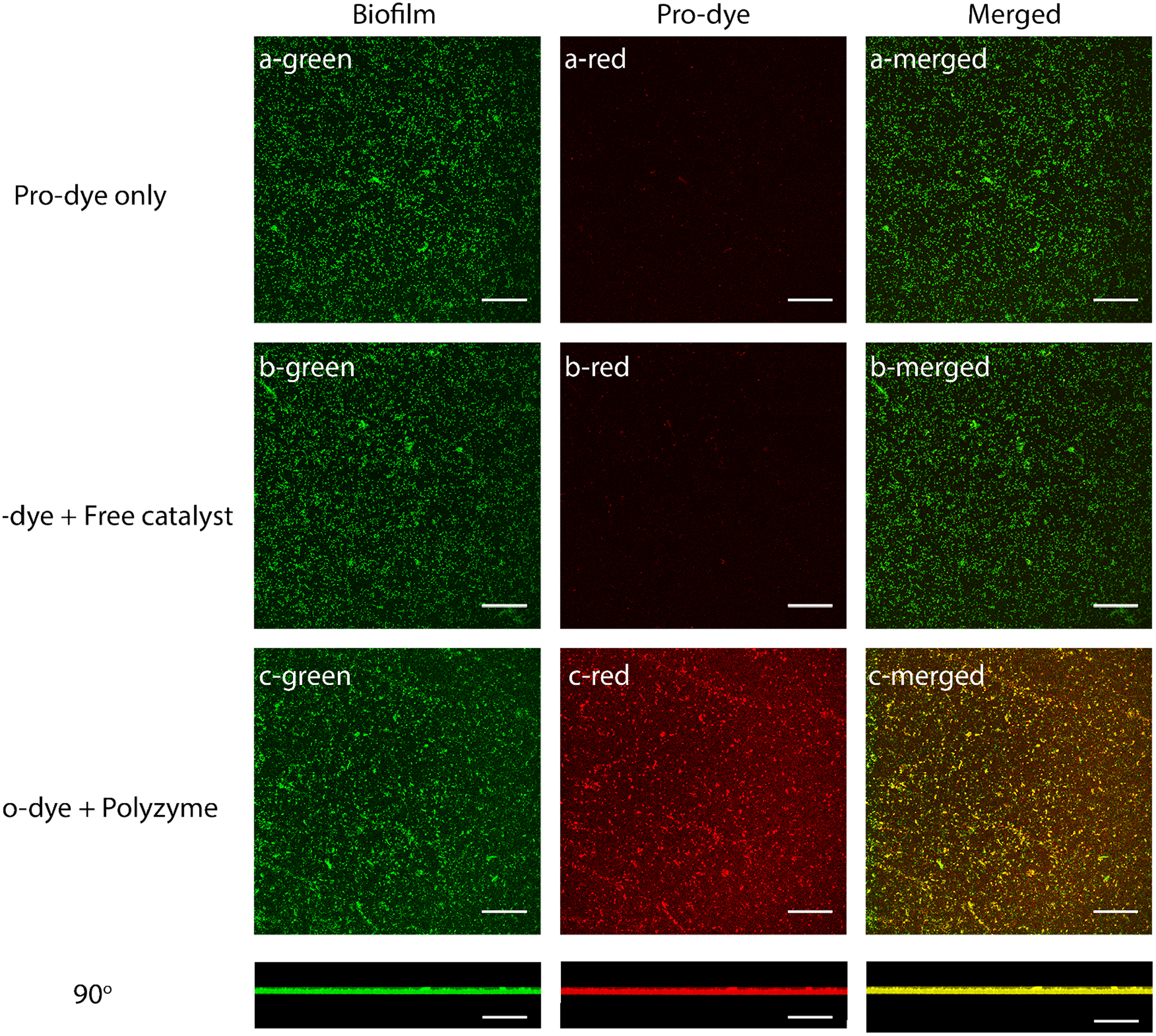

Figure 3.

Polyzyme analog (200 nM) diffusion into GFP - expressing E. coli (CD-2) biofilms after incubation for 1hr in M9 media, as measured by confocal microscopy images. (a) free TPP, (b) encapsulated TPP. Scale bars are 50 μm. 1 mM GSH was used as the cofactor.

Catalytic efficacy of polyzymes in biofilms.

Having established biofilm penetration, the catalytic activity of polyzymes was studied in biofilms through pro-dye activation. GFP - expressing E. coli biofilms were first incubated with the polyzyme for 1 hr in M9 media to internalize the catalyst. Bacterial biofilms were then washed with PBS three times to remove any polyzyme from the surface of the biofilm. Next, fresh M9 media containing the pro-resorufin was added, followed by a 1-hour incubation. Biofilms incubated with substrate alone served as the negative control (Figure 4). By analyzing the red channel, it can be observed that in the presence of polyzyme pro-resorufin was activated in biofilms and showed bright fluorescence. (Quantitative enhancement of fluorescence intensity is in Figure S4, Supporting Information). Biofilms first treated with pro-dye or pro-dye and free TPP catalyst only exhibited negligible fluorescence. In merged channels, the colocalization of the generated red fluorophore and GFP - expressing E. coli biofilms demonstrates that the activated resorufin was distributed within the biofilm, consistent with the catalyst distribution observed in the biofilm.

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy images of biofilms treated with polyzyme (1 hr, 200 nM) followed by incubation with pro-dye (1 hr, 4 μM); negative controls are biofilms incubated with (a) pro-dye only and (b) free catalyst followed by incubation with pro-dye. Scale bars are 50 μm. 1 mM GSH was used as the cofactor.

Antimicrobial activity through activation of prodrugs using polyzymes.

We next carried out prodrug activation using the polyzyme. Two fluoroquinolones, moxifloxacin and ciprofloxacin, were chosen as the antimicrobial agents owing to their broad-spectrum activities.49 These drugs was converted into prodrugs via functionalization on their secondary amino groups (Figure 5a, 5b), as modification at this site blocks the binding to their two target enzymes, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV.50 A bulky aryl-azide carbamate moiety was introduced as a caging group to turn moxifloxacin or ciprofloxacin into a prodrug, reducing both of their antimicrobial activities by more than two orders of magnitude (see Table S1 for planktonic bacteria and Figure S6 for biofilms,).

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the activation of (a) pro-Moxifloxacin and (b) pro-Ciprofloxacin. 1 mM GSH was used as the cofactor. (c)Viability of E. coli (CD-2) biofilms incubated with polyzyme (2 hrs, 200 nM) followed by treatment with prodrugs (6 hrs). (d) Viability of P. aeruginosa (ATCC-27853) biofilms incubated with polyzyme (2 hrs, 1 μM) followed by treatment with prodrugs (6 hrs). Biofilms treated with prodrug, drug and prodrug + polymers were used as controls. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviation.

To demonstrate the generality of this prodrug strategy, promoxifloxacin was used to treat a uropathogenic clinical isolate, E. coli (CD-2) while pro-ciprofloxacin was applied to treat P. aeruginosa (ATCC-27853). Biofilms were incubated in M9 media for 2 hrs with polyzyme at concentrations of 200 nM and 1 μM, respectively. After washing three times using PBS, biofilms were then incubated with different concentrations of prodrugs. In these experiments, biofilms treated with prodrug only and the combination of prodrug and polymer were used as negative controls while those incubated with drugs were used as positive controls. After incubating for 6 hrs, biofilm viability was determined using an Alamar Blue assay.

Figure 5c and 5d show the results obtained from bacterial biofilms exposed to each treatment. As expected, in the presence of the polyzyme, biofilms treated with prodrug exhibited significant decreased viability with efficacy essentially identical to moxifloxacin. In contrast, biofilms treated with prodrug alone demonstrated negligible toxicity at any concentration studied. Similarly, the combination of prodrug and the polymer did not show toxicity to biofilms, indicating that prodrug activation was mediated by catalyst loaded in the polymer rather than polymer itself. The antimicrobial efficacy of this strategy was also validated against planktonic bacteria (Figure S5, Supporting Information).

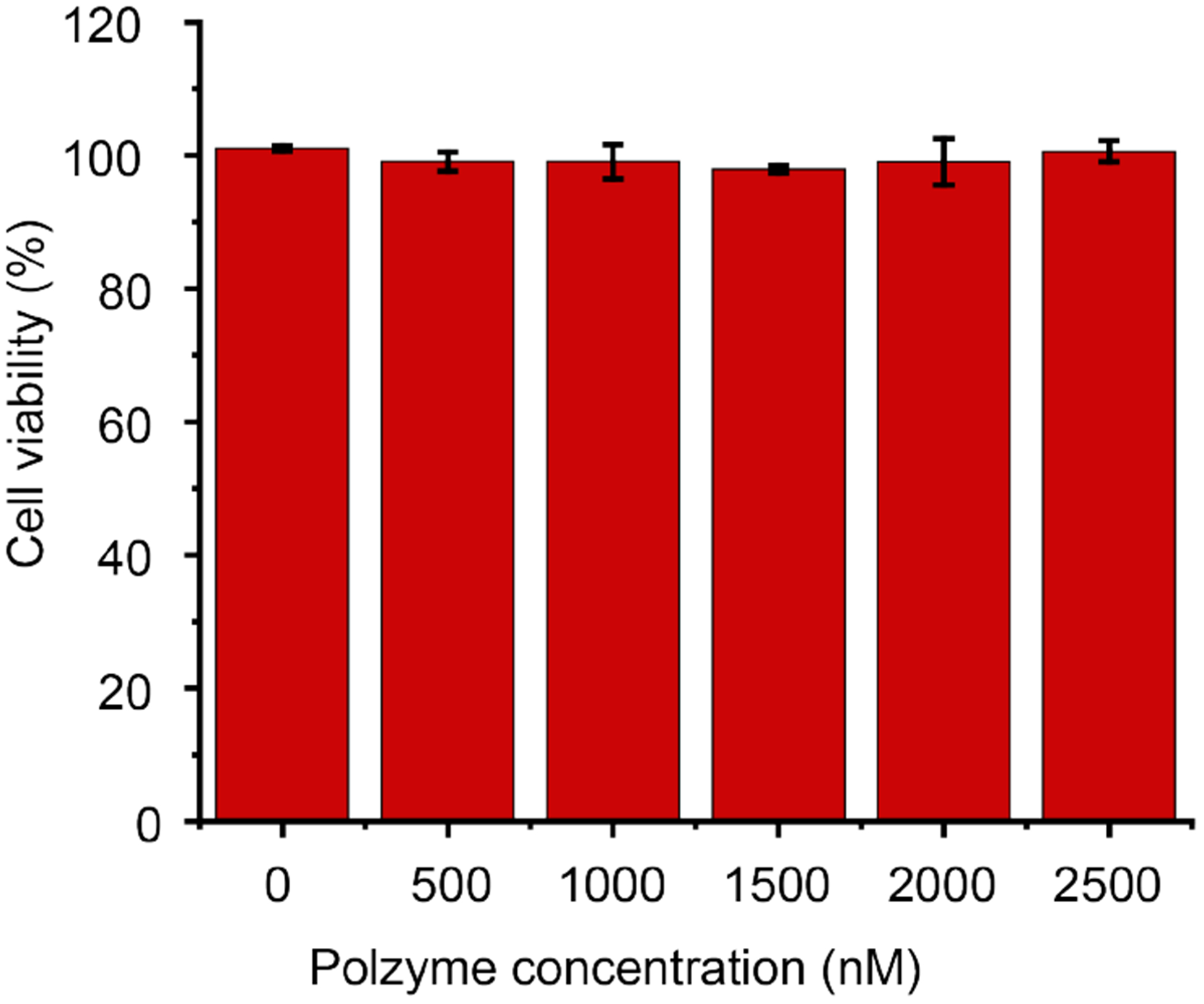

Cytotoxicity assessment of polyzymes with mammalian cells.

We chose fibroblast cells for these studies due to their importance in the wound healing process.51 investigated the cytotoxicity of polyzymes to mammalian NIH 3T3 (ATCC CRL-1658) fibroblast cells.

Fibroblast cells were incubated with polyzymes and cell viability quantified using an Alamar Blue assay. As shown in Figure 6, no acute cytotoxicity of polyzymes was observed at any concentrations used for biofilm treatment. This result suggests that our polyzyme is a promising candidate to eliminate pathogenic biofilms in the presence of mammalian cells, important for wound therapy.

Figure 6.

Viability of 3T3 fibroblast cells after treating with polyzyme for overnight. Each result is an average of three experiments, and the error bars designate the standard deviations.

Conclusion

In summary, we have described a new platform for the application of bioorthogonal transition metal catalysts (TMCs) in complex biological milieus. The catalytic polyzyme is comprised of self-assembled polymer nanoparticles functionalized with hydrophobic side chains to encapsulate TMCs. Loading TMCs into the polymeric nanoparticles enhances their stability and water solubility. The potential therapeutic application of these polyzymes was demonstrated via antimicrobial studies. Polyzymes featuring cationic surface functionality provides the ability to penetrate into bacterial biofilms. Significantly, polyzymes exhibit excellent catalytic efficiency for drug activation and demonstrate high antimicrobial activity within the biofilms at concentrations that do not compromise the fibroblast cell viability. Taken together, polyzyme-polyzymes provide a versatile strategy with potential in antimicrobial therapies as well as broader biomedical applications where in situ drug uncaging can be utilized.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by NIH EB022641 and AI134770.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing final interest.

Supporting Information. Materials; Synthesis of the oxanorbornene Polymer; Synthesis of the polyzyme; Methods of DLS and TEM; Zeta potential of the polyzyme; Quantification of [Fe(TPP)]Cl loaded in polyzyme; Catalytic activity of Nanozymes; Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and Minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) of Mox, Cip, pro-Mox and pro-Cip; Quantitative enhancement of fluorescence intensity in confocal study; Antimicrobial activity test with planktonic bacterial cells; Activation of pro-dye and prodrug in bacterial biofilms; Crystal violet assay; Synthesis of Pro-Resorufin and the intermediates; Synthesis of Pro-Mox and Pro-Cip;

REFERENCES

- 1.Prescher JA; Bertozzi CR Chemistry in Living Systems. Nat. Chem. Biol 2005, 1, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sletten EM; Bertozzi CR From Mechanism to Mouse: A Tale of Two Bioorthogonal Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 666–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sletten EM; Bertozzi CR Bioorthogonal Chemistry: Fishing for Selectivity in a Sea of Functionality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2009, 48, 6974–6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce M; Bertozzi CR Bringing Chemistry to Life. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 638–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabatino V; Rebelein JG; Ward TR “Close-to-Release”: Spontaneous Bioorthogonal Uncaging Resulting from Ring-Closing Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 17048–17052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clavadetscher J; Hoffmann S; Lilienkampf A; Mackay L; Yusop RM; Rider SA; Mullins JJ; Bradley M Copper Catalysis in Living Systems and In Situ Drug Synthesis. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2016, 55, 15662–15666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai Y; Chen J; Zimmerman SC Designed Transition Metal Catalysts for Intracellular Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 1811–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusop RM; Unciti-Broceta A; Johansson EMV; Sánchez-Martín RM; Bradley M Palladium-Mediated Intracellular Chemistry. Nat. Chem 2011, 3, 239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streu C; Meggers E Ruthenium-Induced Allylcarbamate Cleavage in Living Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2006, 45, 5645–5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Völker T; Dempwolff F; Graumann PL; Meggers E Progress towards Bioorthogonal Catalysis with Organometallic Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2014, 53, 10536–10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czuban M; Srinivasan S; Yee NA; Agustin E; Koliszak A; Miller E; Khan I; Quinones I; Noory H; Motola C; Volkmer R; Di Luca M; Trampuz A; Royzen M; Mejia Oneto JM Bio-Orthogonal Chemistry and Reloadable Biomaterial Enable Local Activation of Antibiotic Prodrugs and Enhance Treatments against Staphylococcus Aureus Infections. ACS Cent. Sci 2018, 4, 1624–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pérez-López AM; Rubio-Ruiz B; Sebastián V; Hamilton L; Adam C; Bray TL; Irusta S; Brennan PM; Lloyd-Jones GC; Sieger D; Santamaría J; Unciti-Broceta A Gold-Triggered Uncaging Chemistry in Living Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56, 12548–12552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Völker T; Meggers E Transition-Metal-Mediated Uncaging in Living Human Cells—an Emerging Alternative to Photolabile Protecting Groups. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 25, 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vidal C; Tomás-Gamasa M; Destito P; López F; Mascareñas JL Concurrent and Orthogonal Gold(I) and Ruthenium(II) Catalysis inside Living Cells. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J; Chen PR Development and Application of Bond Cleavage Reactions in Bioorthogonal Chemistry. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X; Huang R; Gopalakrishnan S; Cao-Milán R; Rotello VM Bioorthogonal Nanozymes: Progress towards Therapeutic Applications. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong Y; Tonga GY; Duncan B; Yan B; Das R; Sahub C; Rotello VM Solubilization of Hydrophobic Catalysts Using Nanoparticle Hosts. Small 2018, 14, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonga GY; Jeong Y; Duncan B; Mizuhara T; Mout R; Das R; Kim ST; Yeh Y-C; Yan B; Hou S; Rotello VM Supramolecular Regulation of Bioorthogonal Catalysis in Cells Using Nanoparticle-Embedded Transition Metal Catalysts. Nat. Chem 2015, 7, 597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Destito P; Sousa-Castillo A; Couceiro JR; López F; Correa-Duarte MA; Mascareñas JL Hollow Nanoreactors for Pd-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling and O-Propargyl Cleavage Reactions in Bio-Relevant Aqueous Media. Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 2598–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei H; Wang E Nanomaterials with Enzyme-like Characteristics (Nanozymes): Next-Generation Artificial Enzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 6060–6093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y; Pujals S; Stals PJM; Paulöhrl T; Presolski SI; Meijer EW; Albertazzi L; Palmans ARA Catalytically Active Single-Chain Polymeric Nanoparticles: Exploring Their Functions in Complex Biological Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 3423–3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unciti-Broceta A; Johansson EMV; Yusop RM; Sánchez-Martín RM; Bradley M Synthesis of Polystyrene Micro-spheres and Functionalization with Pd0 Nanoparticles to Perform Bioorthogonal Organometallic Chemistry in Living Cells. Nat. Protoc 2012, 7, 1207–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J; Wang X; Wang Q; Lou Z; Li S; Zhu Y; Qin L; Wei H Nanomaterials with Enzyme-like Characteristics (Nanozymes): Next-Generation Artificial Enzymes (II). Chem. Soc. Rev 2019, 48, 1004–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharifi M; Faryabi K; Talaei AJ; Shekha MS; Ale-Ebrahim M; Salihi A; Nanakali NMQ; Aziz FM; Rasti B; Hasan A; Falahati M Antioxidant Properties of Gold Nanozyme: A Review. J. Mol. Liq 2020, 297. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y; Jin Y; Cui H; Yan X; Fan K Nanozyme-Based Catalytic Theranostics. RSC Adv. 2019, 10, 10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh S Nanomaterials Exhibiting Enzyme-Like Properties (Nanozymes): Current Advances and Future Perspectives. Front. Chem 2019, 7, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang P; Wang T; Hong J; Yan X; Liang M Nanozymes: A New Disease Imaging Strategy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 2020, 8, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A; Das R; Yesilbag Tonga G; Mizuhara T; Rotello VM Charge-Switchable Nanozymes for Bioorthogonal Imaging of Biofilm-Associated Infections. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das R; Landis RF; Tonga GY; Cao-Milán R; Luther DC; Rotello VM Control of Intra- versus Extracellular Bioorthogonal Catalysis Using Surface-Engineered Nanozymes. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 229–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walther R; Rautio J; Zelikin AN Prodrugs in Medicinal Chemistry and Enzyme Prodrug Therapies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2017, 118, 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sancho-Albero M; Rubio-Ruiz B; Perez-Lopez AM; Sebastian V; Martin-Duque P; Arruebo M; Santamaria J; Unciti-Broceta A Cancer-Derived Exosomes Loaded with Ultrathin Palladium Nanosheets for Targeted Bioorthogonal Catalysis. Nat. Catal 2019, 2, 864–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss JT; Dawson JC; Fraser C; Rybski W; Torres-Sánchez C; Bradley M; Patton EE; Carragher NO; Unciti-Broceta A Development and Bioorthogonal Activation of Palladium-Labile Prodrugs of Gemcitabine. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 5395–5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss JT; Dawson JC; Macleod KG; Rybski W; Fraser C; Torres-Sánchez C; Patton EE; Bradley M; Carragher NO; Unciti-Broceta A Extracellular Palladium-Catalysed Dealkylation of 5-Fluoro-1-Propargyl-Uracil as a Bioorthogonally Activated Prodrug Approach. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss JT; Carragher NO; Unciti-Broceta A Palladium-Mediated Dealkylation of N-Propargyl-Floxuridine as a Bioorthogonal Oxygen-Independent Prodrug Strategy. Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 9329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramasamy M; Lee J Recent Nanotechnology Approaches for Prevention and Treatment of Biofilm-Associated Infections on Medical Devices. Biomed Res. Int 2016, 2016, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donlan RM Biofilms and Device-Associated Infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis 2001, 7, 277–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viola GM; Darouiche RO Cardiovascular Implantable Device Infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep 2011, 13, 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flemming HC; Wingender J; Szewzyk U; Steinberg P; Rice SA; Kjelleberg S Biofilms: An Emergent Form of Bacterial Life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2016, 14, 563–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flemming HC; Neu TR; Wozniak DJ The EPS Matrix: The “House of Biofilm Cells.” J. Bacteriol 2007, 189, 7945–7947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart PS; Costerton JW Antibiotic Resistance of Bacteria in Biofilms. Lancet. 2001, 358, 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderl JN; Franklin MJ; Stewart PS Role of Antibiotic Penetration Limitation in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Biofilm Resistance to Ampicillin and Ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 1818–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L-S; Gupta A; Rotello VM Nanomaterials for the Treatment of Bacterial Biofilms. ACS Infect. Dis 2016, 2, 3–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X; Yeh Y-C; Giri K; Mout R; Landis RF; Prakash YS; Rotello VM Control of Nanoparticle Penetration into Biofilms through Surface Design. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 282–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta A; Landis RF; Li C-H; Schnurr M; Das R; Lee Y-W; Yazdani M; Liu Y; Kozlova A; Rotello VM Engineered Polymer Nanoparticles with Unprecedented Antimicrobial Efficacy and Therapeutic Indices against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria and Biofilms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 12137–12143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sasmal PK; Carregal-Romero S; Han AA; Streu CN; Lin Z; Namikawa K; Elliott SL; Köster RW; Parak WJ; Meggers E Catalytic Azide Reduction in Biological Environments. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 1116–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Connor LJ; Mistry IN; Collins SL; Folkes LK; Brown G; Conway SJ; Hammond EM CYP450 Enzymes Effect Oxygen-Dependent Reduction of Azide-Based Fluorogenic Dyes. ACS Cent. Sci 2017, 3, 20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorska K; Manicardi A; Barluenga S; Winssinger N DNA-Templated Release of Functional Molecules with an Azide-Reduction-Triggered Immolative Linker. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 4364–4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matikonda SS; Fairhall JM; Fiedler F; Sanhajariya S; Tucker RAJ; Hook S; Garden AL; Gamble AB Mechanistic Evaluation of Bioorthogonal Decaging with Trans-Cyclooctene: The Effect of Fluorine Substituents on Aryl Azide Reactivity and Decaging from the 1,2,3-Triazoline. Bioconjug. Chem 2018, 29, 324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caeiro J-P; Iannini PB Moxifloxacin (Avelox®): A Novel Fluoroquinolone with a Broad Spectrum of Activity. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther 2003, 1, 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliphant CM; Green GM Quinolones: a comprehensive review Am. Fam. Physician 2002, 65, 455–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun BK; Siprashvili Z; Khavari PA Advances in Skin Grafting and Treatment of Cutaneous Wounds. Science, 2014, 346, 941–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.