Highlights

-

•

Primary Question: What are the experiences and needs of caregivers of persons with dementia in India during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

•

Main finding: Caregivers of persons with dementia during the pandemic experience a set of unique issues that directly related to their care-giving role and another set of issues that did not directly relate to their care-giving role. These contribute to the immediate and long-term needs of the caregivers.

-

•

Meaning of the finding: Interventions for caregivers of persons with dementia during the pandemic should be pragmatic and multilayered, and should address both their immediate and long-term needs.

Key Words: Dementia, COVID-19, pandemic, disaster, needs, caregivers, India, low and middle-income country

Abstract

Objective

To describe the experiences and needs of caregivers of persons with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in a city in India.

Design

Qualitative study using a telephonic semistructured interview.

Setting

A specialist geriatric outpatient mental health service based in a nongovernmental organization in Chennai, India.

Participants

A purposive sampling of family members of persons with dementia registered in the database and seen within the previous 6 months.

Results

Thirty-one caregivers participated. Thematic analysis of the data showed two sets of issues that the caregivers of persons with dementia faced in their experiences during the pandemic. The first set was unique to the caregivers that directly related to their caregiving role, while the second set did not relate directly to their caregiving role. These two sets also appeared to have a two-way interaction influencing each other. These issues generated needs, some of which required immediate support while others required longer-term support. The caregivers suggested several methods, such as use of video-consultations, telephone-based support and clinic-based in-person visits to meet their needs. They also wanted more services postpandemic.

Conclusion

Caregivers of persons with dementia had multiple needs during the pandemic. Supporting them during these times require a pragmatic multilayered approach. Systemic changes, policies and frameworks, increased awareness, use of technology, and better access to health are necessary.

INTRODUCTION

The current pandemic caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak has forced several countries to go under a lockdown.1 The first case of corona virus disease (COVID-19) was identified in India on 30th January 2020 and the country has been under lockdown since 24th March 2020.2

Isolation and quarantine, essential during pandemics, cause distress and fear in the larger community.3 , 4 Elderly with chronic illnesses are shown to experience higher rates of stress, anxiety and depression.5 People with dementia are generally more vulnerable to COVID-19.6 They might not understand information about COVID-19 and might have trouble in following safety procedures such as wearing masks and maintaining personal hygiene.7 Those with dementia might also have limited access to healthcare services and hospitals.8

India has about 5.3 million persons with dementia.9 The severity of dementia, behavioral symptoms, time spent caring, being a woman caregiver, and cutting back on work have all been associated with increased caregiver burden.10 The needs of caregivers and PwD were many even before the pandemic, including, building capacity within the health services, dementia-friendly, and cost-effective services.11 While there is an emerging body of literature on elderly and dementia care during disasters worldwide,5 , 12, 13, 14 very little is known about the experiences of those with dementia and their caregivers during disasters in India. In this paper, we describe the experiences and needs of caregivers of persons with dementia (PwD) during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in a city in India. We present a model to understand their experience and needs. We also highlight potential methods to provide support to meet these needs.

METHODS

Participants

Caregivers of PwD were recruited from a geriatric outpatient mental health service run by a nongovernmental organization, Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF) in Chennai, India. Family members of all PwD registered in the database and seen between 1st September 2019 and 29th February 2020 (6 months) were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in a semistructured telephone interview. Purposive sampling was used to include different socio-economic backgrounds, severity, and types of dementia, and obtain an equal distribution of gender (both caregivers and PwD). Household monthly income was used to determine the socio-economic status.

The inclusion criteria were:

-

1.

A family member providing care for and living with the PwD;

-

2.

Aged 18 and above;

-

3.

The PwD must have a confirmed clinical diagnosis of any type of dementia.

The Institutional Ethics Committee at SCARF approved this study. All participants were required to provide voluntary consent. Due to the existing circumstances of the pandemic and the lockdown informed verbal consent was obtained by telephone.

Procedure

Consultant Psychiatrists who assessed the PwD and interacted with the caregivers during their visits to the service previously, conducted the telephonic interviews. A survey form was used to collect information such as demographic details, last recorded clinical dementia rating (CDR)15 score of the PwD (taken from the case notes; within last 6 months), changes in routine, access to help, etc. The semistructured interview included open-ended questions to allow the participants to describe their experiences.

The interviews were conducted in Tamil and English. All Tamil interviews were translated and transcribed to English by the bi-lingual researchers who conducted the interviews. The context and the meaning of the responses were retained carefully during the translation. Three researchers coded the transcriptions independently. A thematic analysis approach was used to collate codes into identifiable categories. A thematic framework was arrived at by consensus.

RESULTS

A total of 153 persons with dementia were seen between 1st September 2019 and 29th February 2020, of whom 88 could be contacted by telephone. Fifty-six caregivers agreed to participate in the telephonic interview. Considering the time-sensitive nature of this work, we decided to stop recruitment when data saturation was achieved at 31 participants.16

The mean age of the selected caregivers was 54.06 years (SD 15.04) and 16 (51.6%) were women. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the sample.

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variable | Number |

|---|---|

| Persons with dementia details | |

| Gender: | |

| Female | 17 (54.8%) |

| Male | 14 (45.2%) |

| Type of dementia: | |

| Dementia in Alzheimer's disease | 13 (41.9%) |

| Vascular dementia | 6 (19.4%) |

| Mixed (Alzheimer's & Vascular) | 5 (16.1%) |

| Frontotemporal dementia | 3 (9.7%) |

| Dementia in Lewy body disease | 3 (9.7%) |

| Dementia in Parkinson's disease | 1 (3.2%) |

| Age (in years) – Mean | 70.68 (SD 9.26) |

| Clinical Dementia Rating scores | |

| CDR 1 | 16 (51.6%) |

| CDR 2 | 11 (35.5%) |

| CDR 3 | 4 (12.9%) |

| Caregiver details | |

| Caregiver age (in years)—Mean | 54.06 (SD 15.04) |

| Caregiver Gender: | |

| Female | 16 (51.6%) |

| Male | 15 (48.4%) |

| Caregiver relationship to PwD | |

| Wife | 11 (35.5%) |

| Son | 8 (25.8%) |

| Husband | 6 (19.4%) |

| Daughter | 5 (16.1%) |

| Grandson | 1 (3.2%) |

| Caregiver marital status | |

| Married | 27 (87.1%) |

| Separated | 2 (6.45%) |

| Single | 2 (6.45%) |

| Caregiver employment status | |

| Employed | 14 (45.2%) |

| Retired | 9 (29%) |

| Homemaker | 7 (22.6%) |

| Student | 1 (3.2%) |

| Caregiver education | |

| Number of years of education – Mean | 14.19 (SD 4.05) |

| Monthly household income (in INR) | |

| 10,000 or less | 4 (12.9%) |

| 10,001–20,000 | 6 (19.3%) |

| 20,001–50,000 | 11 (35.5%) |

| 50,001–75,000 | 4 (12.9%) |

| 75,001–100,000 | 3 (9.7%) |

| More than 100,000 | 3 (9.7%) |

| Monthly household income (INR)—Mean | 51,790.32 (SD 51,845.57) |

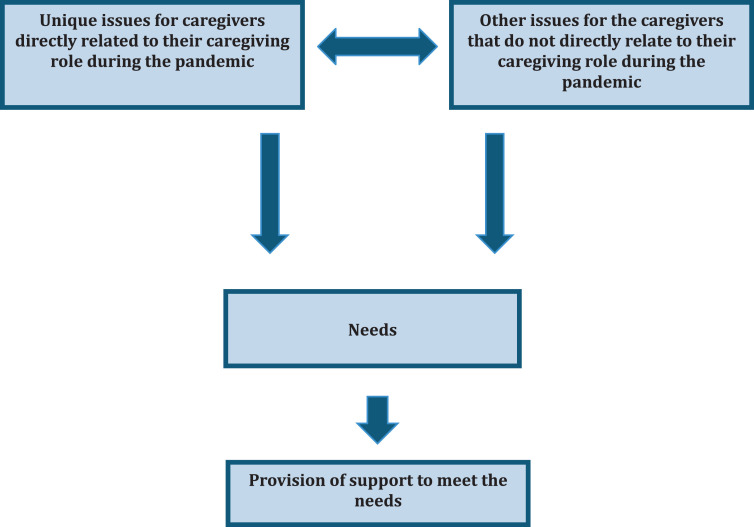

The emergent themes from the qualitative analysis are presented in a model below (Fig. 1 ). This shows how issues, which are unique for the caregivers of PwD that directly related to their caregiving role during the pandemic and issues that do not relate directly to their caregiving role during the pandemic, contribute to the needs of the caregivers.

FIGURE 1.

Model to understand the needs of caregivers of persons with dementia during the pandemic.

Unique issues for caregivers that directly relate to their caregiving role during the pandemic and the lockdown

-

a)

Protecting the PwD from SARS CoV-2 infection

Caregivers reported their worries about protecting their relatives with dementia from the SARS CoV-2 infection.

“We are worried that he may not be able to report mild early symptoms. We try to protect him from exposure now but we are struggling to keep him inside the apartment.”

The caregivers were also concerned about PwD maintaining hand hygiene, using a facemask, and keeping social distancing norms.

“We cannot explain to him about keeping a distance from others and he will not follow; he can become irritable on prompting.”

-

b)

Managing the PwD if they were to be hospitalized, isolated or quarantined

Caregivers also reported that the PwD under their care would not be able to cope by themselves or being looked after by strangers if hospitalized due to COVID-19.

“He will not cope in a general ward for COVID 19 patients. He needs special care from people who can also understand dementia. He cannot be managed otherwise.”

-

c)

Dealing with the changes in the daily routines/activities for the PwD

Many caregivers needed to deal with the changes in the daily routines, level of activities, and social connections of the PwD since the start of the pandemic and the lockdown. Many PwD were not able to go outdoors and engage in activities that used to keep them occupied, hence, caregivers were concerned about not being able to engage their relatives with dementia in activities inside the house.

“She used to have physiotherapy, piano classes, and yoga classes. Also she used to attend the day center…. All that has stopped.”

The husband of a lady with frontotemporal dementia reported a unique problem.

“She likes only to do word puzzles. But now we have run out of paper and shops are closed. I tried to make her do coloring by numbers or other activities on the Internet. She is not very keen.”

The daughter of a lady with dementia said this about the lack of visitors for her elderly parents and raised a very pertinent question:

“Isolation and overprotection affects the quality of life of the elderly, especially those with dementia. After all, what is the point in protecting life if they cannot live it?”

-

d)

Attending to the health and wellbeing of PwD

Many PwD had at least one co-morbid health condition. Some experienced an exacerbation of existing problems.

“My husband has eczema that got worse.”

Others developed a new problem during the pandemic and the lockdown.

“He developed a fever for a day but settled the next day. I got very worried that this was due to Coronavirus”

Some caregivers reported changes in the diet and levels of physical activity for the PwD during the lockdown with most of them having a decline in daily exercise because they were unable to go outdoors.

“He likes non-vegetarian food. Now we are giving him only vegetarian food as we were told that non-vegetarian food is not advised now…. He at times says he does not want to eat.”

“He is not able to go out for walks, police ask us to go back home.”

“Afraid to take her out. Worry about her catching the infection.”

-

e)

Managing Behavior and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia (BPSD)

Most participants reported the presence of BPSD in their relatives with dementia. Some reported specific issues with the start of the pandemic such as getting upset about wearing facemasks or others wearing facemasks, watching the news and becoming anxious, sleep disturbances, and being very disruptive to others at home.

“He comes and bangs on the door when I am in a call as I am working from home now. He doesn't like the doors being closed.”

“Since the lockdown, my husband (son-in-law of the PwD) has been working from home and does video calls. She thinks that he is complaining about her in the calls and comes near him and says, " I don't know anything."

Some reported worsening physical health problems contributing to BPSD.

“He picks his skin from eczema and throws it around sometimes even at me and the attender.”

Other issues for the caregivers that do not directly relate to the caregiving role during the pandemic

-

a)

Managing daily household chores and supplies

An elderly lady looking after her husband with dementia (CDR 1) coped well with paid help to manage the chores and assist her husband's care. However, after the lockdown, her helpers could not come. She could not manage to do the chores and also attend to her husband.

“Unable to manage all the chores by myself and also help him (husband) as home help stopped. Needed to move to my daughter's house for help.”

-

b)

Disruption of work and financial worries

Many caregivers had to start working from home due to the lockdown or faced disruptions to their work. They had concerns about the financial impact of the lockdown.

“I am not able to go to work.….. so there has been a loss in income.”

-

c)

Caregiver health and wellbeing

Caregivers also reported developing health problems themselves and difficulty getting help for the same.

“Unable to access my eye doctor as I have had retinal tears that need regular reviews; also unable to access my dentist.”

-

d)

Worries about caregiver being infected or quarantined due to COVID-19

The caregivers were concerned about being infected with the SARS CoV-2 and being hospitalized or isolated away from their relatives with dementia.

“Don't know how my husband will manage without me.”

-

e)

Stigma about COVID-19

The stigma of COVID-19 worried some caregivers as well. The local authorities were sticking a notice of containment on the doors of homes with COVID-19 and this made them worry.

“I am worried about neighbors complaining if someone in my house is infected. I am worried about the notice being stuck on my door.”

These issues also had an impact on the caregiving role, albeit indirectly. The caregivers were providing care for the PwD before the pandemic by having a network of both formal and informal support to help them with their daily needs. With the start of the pandemic and the lockdown, many caregivers were unable to access these sources of support. This had a significant impact on their caregiving responsibility.

Interaction between “the unique issues for caregivers directly related to their caregiving role” and “the other issues that did not relate directly to their caregiving roles”

Many a time the issues that were unique for the caregiving role and other issues that did not relate directly to caregiving role had two-way interactions influencing each other. For example, a PwD (CDR 3) could not go out for walks due to the lockdown and his BPSD increased. His son, the caregiver, had to work from home due to the lockdown, a situation common to many people in the community. To work from home, the son had to close the door in his room to attend video calls. This, unfortunately, disturbed his father with dementia who did not like the door being closed and started banging on this. As a result, the son could not work effectively from home.

NEEDS

The needs for caregivers could broadly be classified as:

-

1.

Immediate needs (during the pandemic)

-

2.

Longer-term needs (postpandemic)

Immediate needs

-

a)

Need for consultation with a specialist

One of the most common needs was the need for consultation with a dementia specialist. Many specifically needed help to manage the BPSD.

“Keeping in contact and being available for support and help.”

-

b)

Access to medicines for dementia

Caregivers reported problems in getting medicines for their relatives with dementia during the lockdown. Those who were concerned about their finances due to the lockdown and loss of earnings specifically asked for the cost of medicines to be subsidized or provided free of cost.

“We can get medicines for his diabetes and hypertension, however, we are not able to get the medicines prescribed from SCARF (Donepezil 10 mg/d and Memantine 20 mg/d). He hasn't been taking medicines for the last 1 1/2 months.”

-

c)

Engaging PwD at home

Another major need was that the caregivers wanted help with engaging their relatives with dementia at home. While some asked for specific interventions like cognitive stimulation therapy their relatives were receiving from the day centers before, others wanted guidance about simple activities or games they could try at home.

“Some means of engaging my mother will be very useful.”

-

d)

Assistance at home for the PwD

Some caregivers who were overwhelmed by their additional work at home following the lockdown asked for arranging help at home to assist the PwD in their day-to-day activities such as washing, eating, and other personal care.

“A person who can stay full time at home to take care of my mother.”

-

e)

Flexible implementation of policies

Caregivers reported facing many problems due to the lockdown and the implementation of some of the policies especially those regarding restriction of travel and availability of nonessential goods.17 The following narratives are from two different caregivers highlight the impact of restrictions on their caregiving experience.

“My father cannot go out for walks here in the city, which makes him very upset and aggressive inside the apartment. So we wanted to take him to our village (about 350 km away) where he could walk around in the garden in our property. Unfortunately, when we asked for permission to travel, this was declined. They (authorities) told me that dementia does not qualify as an emergency health problem and only those with emergency health problems can travel.”

“He scratches himself all the time and we give him a softball in his hands so he would scratch that rather than himself. Now, this ball is worn out and we could not get him a new one as it is not considered an "essential item" and will not be delivered. Also, all the shops are closed. He is scratching himself all over now and I am very worried.”

Long term needs

Caregivers also reported many long-standing problems, which they expected to continue after the pandemic, and wanted help for these. Trained home care support for persons with dementia, caregiver training, respite services, and improved awareness about dementia in society were some of their needs.

“Need someone who can understand and look after my wife in my absence after the lockdown.”

PROVIDING SUPPORT TO MEET THE NEEDS

The participants had many suggestions about how support could be provided to meet their needs.

-

a)

Use of video-consultations

Many caregivers wanted assessments of their relatives with dementia with the specialist, medication reviews, cognitive stimulation, and engagement, as well as advice and support for the caregivers to be delivered by video calls.

“Once in a month review and adjustment of medications will be helpful.”

“Video calls to engage her in some activities as she used to have them in the day center.”

However, some caregivers did not want to use video calls and the reasons were:

-

1.

Lack of experience and knowledge about using technology

“I do not know how to use a computer or a big (smart) phone.”

-

2.Lack of access to technology“We don't have a computer or a smartphone”

-

3.

PwD unable to participate in a video call

“My mother will not cooperate as she is not comfortable with watching people speaking on a screen.”

-

4.

Ease of access to in-person service

“We live very close to the hospital."

-

5.

No perceived immediate need that can only be met by video calls

“No problems now, a telephone call should be enough to speak to someone. Maybe in the future.”

-

b)

Telephone-based support

Few asked for telephone consultations with the specialists and wanted the pictures of prescriptions for medicines to be sent in a WhatsApp message.

“Support will be appreciated through phone consultations if problems arise during this lockdown.”

-

c)

Clinic-based in-person visits as before

Very few wanted in-person visits to the clinic as before. They were aware of the risks of infection and practical problems in visiting the clinic due to a lack of transport and restrictions on movement.

“We have to come in person. Know the risks but have no option as we need to get the medicines.”

-

d)

Providing support after the pandemic

Caregivers also wanted help with the increased availability of services postpandemic. Raising awareness in the community, among policymakers and enforcers of the policies was mentioned. They wanted better policies to meet their needs.

“The police did not permit us to travel to our village where my father would be more settled. They did not know what dementia was. This is not just a problem for now. Even after the pandemic, something should be done to make them aware of dementia”

DISCUSSION

India, like many other developing countries, is seeing a massive rise in the elderly population and also those with dementia.9 Families provide care for most PwD in India.10 In a setting with a low resource, lack of organized service availability, and increased dependency on families to provide informal support,18 the pandemic and lockdown have compounded the problems for the caregivers. In addition to dealing with what everyone else has to face (restrictions to movement, managing daily chores, disruption of work, and loss of income) these caregivers also have to provide care for their relatives with reduced access to help and support.

A caregiver's experience of looking after a PwD is influenced by many factors including the nature of the relationship between the caregiver and the PwD, the extent of dependency, the severity of BPSD, social life restrictions, role conflicts, perceived competence of caregivers, and role captivity.19, 20, 21, 22 The availability of social support and formal services mediate the influence of all other factors. The pandemic and the lockdown affect many of the factors such as availability and access to formal services, social support, respite, BPSD, role conflicts, impact on career, etc, as seen from our findings.

While planning interventions, priority has to be the provision of immediate support for the caregivers and the PwD. The use of nontraditional methods to deliver dementia care like video-consultations and telephone calls could be tried.23 While this may help reach some, it may not be feasible to shift all support to such technology-based solutions.24 Lack of access to technology, lack of knowledge in using technology, and difficulty in engaging persons with more advanced dementia or severe BPSD were important impediments to use technology in our setting. Health services need to adopt a pragmatic approach that uses technology when feasible and continues to provide in-person clinical service with safety measures including provision of Personal Protection Equipment for all staff and maintaining social-distancing norms.25

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has published a generic health advisory for the elderly in India26 and also a directive was passed to provide curfew passes for paid care workers of those with disabilities.27 These steps though in the right direction merely scratch the surface of what is needed. The caregivers in our study reported the negative impact of the restrictions on their relatives, which made their caregiving role more difficult. A clear policy to direct support for PwD and caregivers is necessary.

Disasters, such as this pandemic, often manifest the pre-existing vulnerabilities in the systems facing the impact of hazards.28 The experiences of the caregivers of PwD during this pandemic have brought to the fore many underlying vulnerabilities in the system. The caregivers in our study have expressed a need for more services and support after the pandemic. A resilience-focused approach29 suggests building capacity within the system to reduce the impact of the hazards on PwD and their caregivers. Most disaster planners do not address adequately the needs of the elderly or those with dementia.12 Lessons learned from this pandemic should push us to build capacity to support the PwD and their caregivers even during “normal” times. This should mitigate the impact of future disasters.

Caregivers face special challenges in caring for their relatives with dementia during the pandemic. They have to balance these with the challenges that they share with everyone during these times. Supporting them during these times requires a pragmatic multilayered approach. Systemic changes, policies, frameworks, increased awareness, use of technology, and better access to health are necessary.

LIMITATIONS

The participants were recruited from one clinical service providing dementia care in India and the sample size was small. Also, only those who could be contacted by telephone were included in the study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sridhar Vaitheswaran MD MRCPsych: Conception and design of work, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising intellectual content.

Monisha Lakshminarayanan MSc: Conception and design of work, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising intellectual content.

Vaishnavi Ramanujam MD: Data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising intellectual content.

Subashini Sargunan MD: Data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising intellectual content.

Shreenila Venkatesan MSc: Analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising intellectual content.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURE

We acknowledge the support of Dr. Thara Rangaswamy, Miss Suhavana Balasubramanian, Miss Nirupama Natarajan, Miss Nivedhitha Srinivasan, Miss Gayathri Nagarajan, & Miss Kowsalya Kumar for their help with the study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts with any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

Funding: No specific funding was received to conduct this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation: WHO announces COVID - 19 outbreak a pandemic [Euro WHO website] March 12, 2020. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic. Accessed May 23, 2020

- 2.Economic Times: India will be under complete lockdown for 21 days: Narendra Modi [ET Online] March 25, 2020. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-will-be-undercomplete-lockdown-starting-midnight-narendra-modi/articleshow/74796908.cms. Accessed May 23,2020

- 3.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1206. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maharaj S, Kleczkowski A. Controlling epidemic spread by social distancing: do it well or not at all. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:679. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picaza Gorrochategi M, Eiguren Munitis A, Dosil Santamaria M. Stress, anxiety, and depression in people aged over 60 in the COVID-19 outbreak in a sample collected in Northern Spain. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Li T, Barbarino P. Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1190–1191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30755-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Li T, Gauthier S. Coronavirus epidemic and geriatric mental healthcare in China: how a coordinated response by professional organizations helped older adults during an unprecedented crisis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y, Li W, Zhang Q. Mental health services for older adults in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e19. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jotheeswaran AT. In: Shaji KS, Jotheeswaran AT, Girish N, editors. Alzheimer's & Related Disorders Society of India; New Delhi: 2010. pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prince M, Brodaty H, Uwakwe R. Strain and its correlates among carers of people with dementia in low-income and middle-income countries. A 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:670–682. doi: 10.1002/gps.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamech N, Raghuraman S, Vaitheswaran S. The support needs of family caregivers of persons with dementia in India: Implications for health services. Dementia. 2019;18:2230–2243. doi: 10.1177/1471301217744613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wingate MS, Perry EC, Campbell PH. Identifying and protecting vulnerable populations in public health emergencies: addressing gaps in education and training. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:422–426. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Sullivan T., Bourgoin M. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2010. Vulnerability in Influenza Pandemic: Looking Beyond Medical Risk.http://icid.com/files/Marg_Pop_Influenza/Lit_Review_-_Vulnerability_in_Pandemic_EN.pdf Available at: Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falconi M, Fahim C, O'Sullivan T. Protecting and supporting high risk populations in pandemic: drawing from experience with influenza A (H1N1) Int J Child Health Hum Dev. 2012;5:373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and Young. Neurology. 1991;41:1588–1592. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.News 18: No Delivery of Non-essentials by E-commerce Sites, Travel Ban: Here's What Will Be Allowed from Today. [News 18 website] April 20, 2020 Available at: https://www.news18.com/news/india/as-delhi-punjab-choose-complete-lockdown-amid-exemptions-heres-whats-allowed-and-prohibited-from-tomorrow-2584217.html. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 18.Shaji KS, Smitha K, Lal KP. Caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease: a qualitative study from the Indian 10/66 Dementia Research Network. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:1–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yates ME, Tennstedt S, Chang B-H. Contributors to and mediators of psychological well-being for informal caregivers. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 1999;54:P12–P22. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.p12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biddle BJ. Recent developments in role theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986;12:67–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaitheswaran S, Raghuraman S, Rangaswamy T. Caregiver stress and interventions. In: Kumar CTS, Shaji KS, Varghese M, Nair MKC, editors. Dementia in India 2020. Alzheimer's and Related Disorders Society of India (ARDSI); Cochin: 2019. pp. 68–73. Cochin Chapter. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenz K, Freddolino PP, Comas-Herrera A. Technology-based tools and services for people with dementia and carers: mapping technology onto the dementia care pathway. Dementia. 2019;18:725–741. doi: 10.1177/1471301217691617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meiland F, Innes A, Mountain G. Technologies to support community-dwelling persons with dementia: a position paper on issues regarding development, usability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, deployment, and ethics. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;4:e1. doi: 10.2196/rehab.6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Emergency Consideration for PPE [CDC website] Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/emergency-considerations-ppe.htmlAccessed May 23, 2020

- 26.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Advisory for Elderly population of India during COVID-19. Available at: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/AdvisoryforElderlyPopulation.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020

- 27.Business Standard: Curfew passess for caregivers of people with disabilities amid lockdown. Available at: https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/ensure-curfew-passes-for-caregivers-of-people-with-disabilities-amid-lockdown-120040100827_1.html. Accessed May 23, 2020

- 28.Zaumseil M, Schwarz S. Springer; 2014. Understandings of coping: A critical review of coping theories for disaster contexts, in Cultural Psychology of Coping with Disasters; pp. 45–83. [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLeod S, Musich S, Hawkins K. The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2016;37:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]