Abstract

This commentary aims to deconstruct xenophobia and its worldwide impact, particularly on people of Asian descent, amid the global COVID-19 pandemic. The commentary begins with an overview of COVID-19’s impact on the United States economy and educational landscape, continues with a discussion about the global history of pandemic-prompted xenophobia and its relationship to sensationalized media discourse, and concludes with recommendations to reconsider various aspects of intercultural communication in relation to public health issues.

Keywords: COVID-19, Xenophobia, Pandemic, Media, Communication, Education

1. Introduction

In the spring of 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic took the world by storm. COVID-19, a highly contagious respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus, prompted a worldwide shutdown of schools, restaurants, and non-essential businesses when countries around the world experienced rampant infections and fatalities. While many public spaces such as P-12 schools (i.e. schools that serve students through primary and secondary grades), restaurants, and non-essential businesses located in highly affected areas closed for a period of at least one month, due to increasing rates of reported infections, the dates for reopening and resuming normal activity were continuously postponed. The purpose of this commentary is to examine xenophobia, the fear or hatred of that which is perceived to be foreign or strange, and its worldwide effect—particularly on people of Asian descent—amid the global pandemic. The commentary begins with an overview of COVID-19’s impact on the United States economy and educational landscape, continues with a discussion about the global history of pandemic-prompted xenophobia and its relationship to sensationalized media discourse, and concludes with recommendations to reconsider various aspects of intercultural communication in relation to public health issues.

2. Impact of COVID-19 on the United States

At the time this commentary was written during the late spring and early summer of 2020, confirmed cases of COVID-19 remain on the rise in the United States (World Health Organization, 2020). Further, there is no confirmed date by which quarantine and social-distancing precautions will officially end and regular activities will resume in America, partially evidenced by universities’ decisions to continue online instruction during fall 2020 (Garber, 2020; White, 2020).

In February and March of 2020, as United States cities such as Seattle, San Francisco, and New York City began to see rapidly increasing numbers of infections and deaths, P-12 schools and universities responded quickly to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recommendations to shift courses online. While some universities cancelled coursework for two or three weeks to provide instructors and administrators adequate time to restructure and consider the access and resource-based limitations of students who would now be required to complete their coursework online, some universities which already had an extensive online presence transitioned relatively seamlessly. In the United States, the events and impacts of COVID-19 have introduced thousands of students, educators, and administrators to direct action related to the value of technology—the types of technology that were unavailable at the time of the influenza pandemic of 1918 or SARS pandemic of 2003, for instance. Evidenced by widespread support and collective action between community members, students, and educational leaders to shift to online teaching and learning, society has firsthand experienced and recognized technology as a necessity during an unanticipated period of extreme peril.

At the same time, despite what might be viewed as a wake-up call for educational and political leaders as well as the general public to understand the value and necessity of technology for teaching and learning, the COVID-19 pandemic has reignited educational inequities that date back to global outbreaks of decades past. Although technology, in essence, saved us from having to shutdown communication, learning, and instruction, technology and the politicized nature of xenophobia have detrimentally impacted educational contexts and society writ large.

3. History of global pandemics, media discourse, and xenophobia

The influenza pandemic of 1918 was a defining moment of public health in United States and universal history. Spreading across the globe with “unprecedented severity and speed” (Parmet & Rothstein, 2018, p. 1435), an estimated 500 million people (or one-third of the world’s population) became infected (CDC, 2019), which resulted in an estimated 20–50 million deaths (CDC, 2019; Taubenberger, Reid, Krafft, Bijwaard, & Fanning, 1997; World Health Organization, 2010). In his article, “Spanish Flu: When Infectious Disease Names Blur Origins and Stigmatize Those Infected”, Hoppe (2018) addresses two relevant issues to contextualize infectious disease naming practices: 1) first is whether, in an age of global hyper-interconnectedness, fear of the other is truly irrational or has a rational basis; and 2) second is the persistence of xenophobic responses to infectious disease in the face of contrary evidence (p. 1462). According to Hoppe (2018), despite the World Health Organization’s (WHO) efforts to discourage using specific people, places, or animals to name infectious diseases, the continued use of stigmatizing monikers such as “Spanish flu”, “Mexican swine flu”, and “Ebola virus” can be psychologically damaging and signify how authorities and the public respond to an epidemic. “Scholars argue that promoting an association between foreigners and a particular epidemic can be a rhetorical strategy for promoting fear or, alternatively, imparting a sense of safety to the public,” and the pervasive use of social media has raised the urgency for officials to disseminate non-stigmatizing names as soon as new diseases are identified (Hoppe, 2018, p. 1462).

Although WHO has since published guidelines on best practices for naming diseases in an effort to curb stigmatized communication (WHO, 2015), in May 1995, Western media coverage of the Ebola outbreak in Zaire began. Ebola, a lethal virus that causes severe bleeding and organ failure, became a real-life outbreak “in a cultural atmosphere already infused with the threat of infection” (Ungar, 1998, p. 45). Ungar (1998) refers to the timing of the Ebola Zaire epidemic as “exquisite” for unleashing a hot crisis; it occurred just after the release of Outbreak (a movie that eerily mirrored the epidemic), prompted an unprecedented frenzy of media coverage, and led various countries to tighten their borders (p. 46). Aligned with Hoppe’s (2018) discussion of xenophobia as a rhetorical strategy, Ungar (1998) describes globalization and othering as “part of the analytical tool kits available to journalists and … agenda-setters” (p. 53).

The media, following their standard practices, initially presented Ebola as the embodiment of the worst of the mutation-contagion package. Numerous references to ‘panic’ over Days 2 and 3 suggest that reporters apprehended an impending epidemic of fear. During these days, the media simultaneously moderated its coverage and shifted to the containment package. It took several days and some deft analytic maneuvers and factual oversights, but the media was able to fashion a package that, at a theoretical level, sequestered the disease by ‘othering’ the situation in Zaire. (Ungar, 1998, p. 52)

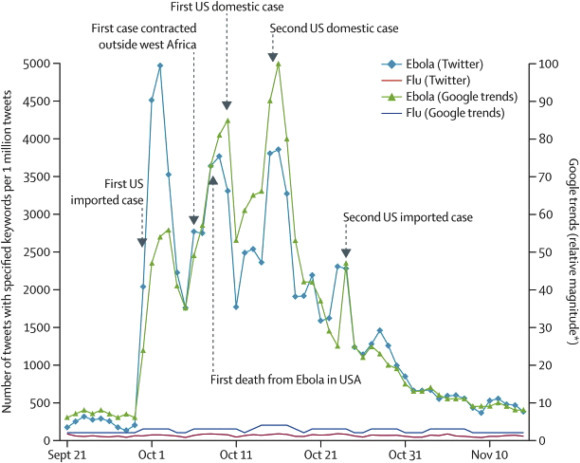

Fast-forward to 2014, the Ebola virus returned and spread to seven more countries including: Italy, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In October 2014, familiar dramatized media coverage in the United States prompted anxiety; however, given the low risk of infection, Fung, Tse, Cheung, Miu, and Fu (2014) suggest that Americans’ fears were driven by perceived rather than actual risk. Aligned with Hoppe (2018) and Ungar’s (1998) discussions regarding the rhetorical influence of media on amplified feelings of fear or serenity, Fung et al. (2014) propose “exaggeration or reassurance from the media can inflame or subdue people’s perceived risk of Ebola infection” (p. 2207). In Fig. 1 , indicating heightened feelings of anxiety, anger, and/or negative emotions, Fung et al. (2014) compare worldwide news spread of Ebola vs. influenza (flu) on Twitter and Google.

Fig. 1.

Temporal trends on Twitter and Google about Ebola and influenza (flu) before, during, and after Ebola cases in the USA, September to November 2014 (Fung et al., 2014).

In 2003, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), a contagious disease similar to COVID-19 in that it was caused by a coronavirus and originated in China, ignited widespread health concerns across two dozen countries in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia (Baker, 2007). In her comparative case study of 5,638 policy responses to SARS disseminated by Canada and the United States, Baker (2007) identifies xenophobic ramifications that not only damage multicultural societies, but a broad spectrum of policy subsystems. For instance, while fear was used to define SARS in both countries, in Canada, core challenges were considered economic and related to the global treatment of Canadians (Baker, 2007). Alternatively, in the United States, fear-driven policy responses and general concerns related to the threat that SARS posed to the health and safety of Americans (Baker, 2007). In her examination of SARS-related public communications across North America, Baker (2007) determines:

Part of the tonal pattern observed in the sample as a whole was that negatively toned titles with potentially xenophobic implications such as “Fear of New Virus Grows as Hong Kong Official Falls Ill” (from the New York Times on March 25th, 2003) appeared contemporaneously with headlines that were either reassuring or which deliberately defined the issue differently such as “U.S. Finds Different Villain in Search for Ailment’s Cause” (from the New York Times on the same day). This pattern represents a delicate balance in public discourse. (p. 1654)

As such, if we wish to combat and overcome xenophobia, we must examine and ameliorate the systems that produce and constrain it.

4. Educational impacts of technology and the politicized nature of xenophobia

Pandemics are not explicitly defined as widespread infectious diseases; rather, they evoke social and political responses that may link to historically-embedded anxieties surrounding “political-economic relations, foreign intervention, conflict or social control” (Leach, 2020, para. 1). In many countries, the stigma of an infectious disease can be worse than the disease itself, as well as play a significant role in social and institutional responses (Barrett & Brown, 2008; Waxler, 1981). Within the United States, for example, much of the media’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak has been a proliferation of sensationalized, misinformed, and xenophobic headlines (Table 1 ). Furthermore, when combined with a misconception of the nature of the etiological agent, hot-button headline phrases such as “killer virus”, “deadly virus”, and “Wuhan virus” promote fear and panic which propel prejudice, xenophobia, and discrimination (Das, 2020; Person, Sy, Holton, Govert, & Liang, 2004). Equally important, communications which normalize racism—especially when they are circulated by prominent universities such as University of California at Berkeley—perpetuate fears and amplify community tensions (Asmelash, 2020). “Previous experimental research has demonstrated that news headlines can have a powerful effect on the attitudes that people adopt (Allport & Lepkin, 1943; Geer & Kahn, 1993; Pfau, 1995; Smith & Fowler, 1982; Tannenbaum, 1953),” emphasizing the importance of monitoring the relationship between media headlines and the stories they lead with essential questions such as: Are they accurate summaries? Or, do other media imperatives—such as the pursuit of a reader’s attention—lead to systematic misrepresentations of the articles they introduce? (Andrew, 2007, p. 25).

Table 1.

COVID-19 headlines, sources, dates of publication, and citations.

| Headline | Source | Date of Publication | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronavirus: Outrage over Chinese blogger eating ‘bat soup’ sparks apology | Fox News | January 28, 2020 | (Gaynor, 2020) |

| UC Berkeley faces backlash after stating ‘xenophobia’ is ‘common’ or ‘normal’ reaction to coronavirus | CNN US | February 2, 2020 | (Asmelash, 2020) |

| What’s spreading faster than coronavirus in the US? Racist assaults and ignorant attacks against Asians | CNN US | February 21, 2020 | (Yan, Chen, & Naresh, 2020) |

| As coronavirus spreads, so does xenophobia and anti-Asian racism | Time | March 6, 2020 | (Haynes, 2020) |

| Fox News and Donald Trump are embracing xenophobia to defend against the coronavirus | BuzzFeed News | March 10, 2020 | (Elder, 2020) |

| No, calling the novel coronavirus the ‘Wuhan virus’ is not racist | USA Today | March 11, 2020 | (Mastio, 2020) |

| “The United States will be powerfully supporting those industries, like Airlines and others, that are particularly affected by the Chinese Virus. We will be stronger than ever before!” -President Trump | Twitter/NBC News | March 16, 2020 | (Yam, 2020) |

| Trump defends using ‘Chinese virus’ label, ignoring growing criticism | The New York Times | March 18, 2020 | (Rogers, Jakes, & Swanson, 2020) |

| Sen. Cornyn: China to blame for coronavirus, because ‘people eat bats’ | NBC News | March 18, 2020 | (Shen-Berro, 2020) |

| Trump on ‘Chinese virus’ label: ‘It’s not racist at all’ | Politico | March 18, 2020 | (Forgey, 2020) |

| Yes, of course Donald Trump is calling coronavirus the ‘China virus’ for political reasons | CNN International | March 20, 2020 | (Cillizza, 2020) |

| Film club: “Coronavirus racism infected my high school” | The New York Times | March 20, 2020 | (The Learning Network, 2020) |

| Spit on, yelled at, attacked: Chinese-Americans fear for their safety | The New York Times | March 23, 2020 | (Tavernise and Oppel, 2020) |

| “They just see that you’re Asian and you are horrible”: How the pandemic is triggering racist attacks | Vox | March 25, 2020 | (Kim, 2020) |

| Asian Americans reported hundreds of racist acts in last week, data shows | Fox News | March 27, 2020 | (Aitken, 2020) |

| ‘They look at me and think I’m some kind of virus’: What it’s like to be Asian during the coronavirus pandemic | USA Today | March 28, 2020 | (Phillips, 2020) |

| Scholars confront coronavirus-related racism in the classroom | Inside Higher Ed | April 2, 2020 | (Redden, 2020) |

| Irony: Hate crimes surge against Asian Americans while they are on the front lines fighting COVID-19 | Forbes | April 4, 2020 | (Gerstmann, 2020) |

| Covid-19 has inflamed racism against Asian-Americans. Here’s how to fight back | CNN | April 11, 2020 | (Liu, 2020) |

| How the coronavirus is surfacing America’s deep-seated anti-Asian biases | Vox | April 21, 2020 | (Zhou, 2020) |

| We are not COVID-19: Asian Americans speak out on racism | Nikkei Asian Review | May 9, 2020 | (Zhou, Yu, & Fang, 2020) |

| US senator criticized for telling students China is to blame for COVID-19 | The Guardian | May 17, 2020 | (Associated Press, 2020) |

| Asian American doctors and nurses are fighting racism and the coronavirus | The Washington Post | May 19, 2020 | (Jan, 2020) |

| I don’t scare easily, but COVID-19 virus of hate has me terrified | ABC News | May 23, 2020 | (Han, 2020) |

| Trump scapegoats China and WHO—and Americans will suffer | Foreign Policy | May 30, 2020 | (Garrett, 2020) |

| Remember, no one is coming to save us | The New York Times | May 30, 2020 | (Gay, 2020) |

| America’s ‘two deadly viruses’–racism and COVID-19-go viral among outraged Twitter users | Forbes | May 31, 2020 | (Voytko, 2020) |

| Protesting racism versus risking COVID-19: ‘I wouldn’t weigh these crises separately’ | National Public Radio (NPR) | June 1, 2020 | (Chappell, 2020) |

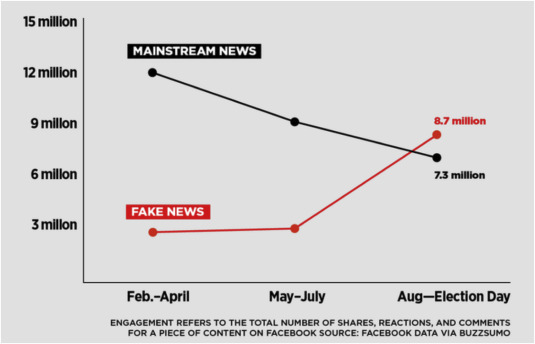

Our reliance on technology and the media for information suggests that adolescents and adults may be susceptible not only to believing the toxic and/or unsubstantiated headlines they read but disseminating “fake news” through their own social media newsfeeds (Rayess, Chebl, Mhanna, & Hage, 2018, p. 146). Based on their review of research that reveals how viral “fake news” stories outperformed “real news” stories during the 2016 presidential election (Silverman, 2016, Table 2 ), Rayess et al. (2018) explain that because people tend to believe the information they read on the internet without skepticism, their credulity results in a faster spread of hot-button fake news than real news.

Table 2.

Total Facebook engagements for top 20 election stories (Silverman, 2016).

As such, “harm can be caused, especially when fake news is disconnected from the original sources or context” (Conroy, Rubin, & Chen, 2015 qtd. in Rayess et al., 2018, p. 147), and the implications for media-influenced xenophobia can be catastrophic (Albright, 2017; Schäfer & Schadauer, 2018; Shimizu, 2020). In response to aggravated hate crimes such as racial taunts on school campuses, shunning on public transit, and cyberbullying on social media, some organizations have responsively and prolifically used media to raise awareness for anti-Asian harassment and promote allyship for those affected (Jeung, Kulkarni, & Choi, 2020).

One example in the United States includes the collaboration between two civil rights and advocacy organizations to create a new online reporting center for incidents of bias against Asian Americans (Redden, 2020). According to the “Stop Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Hate” project data shared by the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council on Affirmative Action, data from April 3, 2020 reveal that 1,135 incident reports of verbal harassment, shunning, and physical assault were received within two weeks. Further, data reveal that AAPI women were harassed at twice the rate of men, and AAPI children/youth were involved in 6.3 percent of the incidents. By April 24, 2020, Stop AAPI Hate had received 1,497 reports which indicate incidents from California and New York constituted over 58 percent of all reports, and AAPI women were harassed 2.3 times more than AAPI men. By May 13, 2020, Stop AAPI Hate had received over 1,710 incident reports from 45 states in the US, where 90 percent of respondents believed they were targeted because of their race. Notable incidents reported by council members Choi, Jeung, and Kulkarni (2020) included, but were not limited to:

-

•

We were having community circle in our grade 4 classroom. One of the students said “kill the Chinese” in Spanish when it was his turn to speak. Many of the Spanish speaking children laughed. I asked to have what he said translated. I explained to the class that the statement was offensive and not part of our norms for community circle. I brought it to the principal’s attention, and she spoke to the student.

-

•

Overheard in public restroom: “Thank god no Chinese children were at soccer practice to infect others.” Tried to correct aspersion, but [I was] totally ignored by white patron.

-

•

My kids were at the park with their dad (who is white). An older white man pushed my 7- year-old daughter off of her bike and yelled at my husband to, “Take your hybrid kids home because they’re making everyone sick.”

-

•

I walked into the train carriage, and immediately two teenage girls started screaming and “ewwwing” and making a show of covering their mouths and faces with a scarf. Then, [they] stood up and ran to the other end of the carriage (which was more crowded) jeering at me.

-

•

A young white girl told her parents she was going to “die” (repeatedly) and her parents asked, “Why?” And she said, “of coronavirus” and pointed in my direction.

-

•

Professor sent an email to all of his students in English class and called COVID-19 the “Wuhan virus.”

-

•

We here holding a public webinar in Chinese on COVID-19 and families. In the last minutes, we were Zoom-bombed by a group and participants were exposed to racist and vulgar images, curses, harassment, and name-calling.

-

•

I was walking my dog at night and a car swerved toward me on the sidewalk. Two guys started shouting, “Trump 2020! Die, chink, die!”

In another example, Rzymski and Nowicki (2020) conducted an anonymous online survey of Asian medical students in Poland to assess whether they experienced prejudice related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey findings from 85 medical students from Asia reveal that the global panic triggered xenophobic reactions toward students before the first case of COVID-19 was even confirmed in Poland (Rzymski & Nowicki, 2020). Results indicate that 61.2 percent of the surveyed students experienced prejudice, 47.1 percent of the prejudice occurred in public transportation and on the street, and prejudice was more frequently encountered by those who wore face masks (71.2 percent) than those who did not (28.2 percent) (Rzymski & Nowicki, 2020). Similar to examples provided by Stop AAPI Hate, reported reactions to Asian students include:

stepping away, changing seats on the bus, being asked to keep the safe distance, covering mouth and nose, showing judgmental facial expressions, pointing with a finger and whispering comments in Polish, spitting, tossing a beer bottle and using offensive language. When indicating how much these situations affected the surveyed students using a Likert scale, a score of 5 was the most frequently selected. (Rzymski & Nowicki, 2020, p. 3)

In another study of COVID-19-influenced discrimination and social exclusion, He, He, Zhou, Nie, and He (2020) collected survey data from Chinese people in mainland China and overseas, as well as descriptive secondary data from sources such as newspapers and Internet publications. Survey data resulted in 17,846 responses from 31 provinces in mainland China and 1,904 responses across 70 countries overseas. Findings indicate that 90 percent of mainland China respondents exhibited discriminatory attitudes toward people from Hubei Province, such as reporting their presence to local authorities, avoiding them, and actively expelling them from their communities (He et al., 2020). In addition, and similar to examples provided by Stop AAPI Hate and Rzymski and Nowicki (2020), 25.11 percent of overseas Chinese residents reported experiencing discrimination, such as being laid off without proper cause, rejected from rental housing, and abused in public spaces (He et al., 2020).

This fear of unknown diseases is a part of human nature, especially when they are deadly and highly infectious. Stigmatization of COVID-19 led by some politicians such as Donald Trump might have reinforced such discrimination and social exclusion … However, it is paramount to recognize the discriminatory behaviors that accompany fear, as they damage not only the socio-cultural fabric in the long-run, but they also compromise present efforts to contain the disease. (He et al., 2020, p. 3)

The aforementioned xenophobic incidents in the United States, Poland, China, and across the world suggest that fear of the unknown is the main driver of xenophobia. Evidenced by numerous xenophobic incidents involving hateful rhetoric, harassment, and physical assaults, the demand for using informed communication strategies in pandemic planning to redress issues of disadvantage and mitigate inequities is indisputable (Lee, Rogers, & Braunack-Mayer, 2008).

5. Social justice and pandemic planning

In 2008, Lee, Rogers, and Braunack-Mayer analyzed the role of communication in addressing issues of social justice among 12 national pandemic plans: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States. Their analysis expanded on a previous study, where Lee and Rogers (2006) identify three features of communication strategies to cultivate social justice amid global crises: 1) ensure equity in access to information; 2) actively redress existing media inequalities; and 3) increase overall levels of information to build legitimacy and trust (p. 224). With the understanding that pandemic planning raises a multitude of practical and ethical issues, for their 2008 study, Lee, Rogers, and Braunack-Mayer were centrally concerned with issues related to disadvantage and vulnerability to infection, the protection (or lack thereof) of underprivileged groups, and the exacerbation of existing inequalities. Through their analysis, Lee et al. (2008) identify four general communication strategies across the 12 pandemic plans: 1) use of the internet to provide information; 2) provision of culturally appropriate information; 3) information sessions for journalists; and 4) media monitoring. However, they also recognized that only three plans referred to disadvantaged groups (Australia, New Zealand, and Norway) and use of the internet was the most common form of strategy communication, which indicates the need for worldwide, all-encompassing, equity-focused pandemic planning strategies to be communicated via online platforms.

6. The role of technology in educational community development

According to Lee et al. (2008), “the Internet has the potential to increase access to information by delivering messages in multiple languages, and by addressing mental and physical barriers to information through tailoring the form and delivery of information” (p. 229). Accordingly, Lee et al. (2008) consider the concerns associated with media use to initiate public discourse and emphasize the importance of “media monitoring” in pandemic planning communications to: 1) redress existing media inequalities such as misrepresentation of particular groups; 1) establish trust with marginalized populations subject to experiencing stigmatization; and 3) assist in the general identification and redirection of misguided reporting, rumors, and misperceptions (p. 231).

Corresponding to the events of COVID-19, in contexts of teaching and learning, administrators, instructors, and other educational leaders have a unique opportunity to use technology to communicate accurate, evidence-based information to students and surrounding communities to elucidate the risks of stigmatization, mitigate the spread of misinformation, and underscore zero-tolerance policies for xenophobia. For example, faculty at one large public university in Western New York circulated the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) guidebook titled, “Ten Equity Implications of the Coronavirus COVID-19 Outbreak in the United States”. Among a barrage of insightful and actionable mass communications surrounding the transition to online learning, the guidebook propounded the comparatively underrepresented social responsibility to “stand up against racial/ethnic discrimination and stereotyping” in the face of pandemic-influenced fear and uncertainty. In addition, with the all-inclusive shift to distance learning, the events of COVID-19 may encourage instructors, students, and educational leaders to evaluate the credibility of sources using methods such as the CRAAP test (Blakeslee, 2004):

-

•

Currency: the timeliness of the information

-

•

Reliability: importance of the information

-

•

Authority: the source of the information

-

•

Accuracy: the reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the information

-

•

Purpose: the reason the information exists

Correspondingly, the events of COVID-19 may encourage instructors, students, and educational leaders to critically discuss the ramifications of consuming and spreading misinformation. In support of this notion, as a result of their study of college students’ use of fake news, Chandra, Surjandy, and Ernawaty (2017) suggest:

The implications of this research [suggest] that higher education or university[ies] can [provide] more socialization to the higher education students about receiving and disseminating the news, as well as the need to understand the importance of including news source[s] and ensuring that the news [is credible and] can be trusted. (p. 54)

As such, in addition to using increased distance learning opportunities to encourage students and surrounding communities to think critically about media and information literacy, as well as dissuade their engagement with and/or utilization of sensationalist propaganda, instructors and educational leaders may constructively take advantage of the shift to online learning and use of virtual platforms as tools for promoting justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

The optimistic view is that social media could prove useful at a time when many of us are otherwise isolated from one another. Conversations around the coronavirus, especially those at the community level, can help us navigate this crisis, says Jeff Hancock, a professor of communication at Stanford University and the director of the Stanford Social Media Lab. Those discussions are “reflecting how society is thinking and reacting to the crisis,” Hancock says (de la Garza, 2020, para.1).

7. Conclusions and recommendations

To address xenophobia, it is essential to understand why certain diseases and social conditions produce fear and discrimination, as well as acknowledge the stigmatization of communities and population groups as a significant challenge to global development (Das, 2020). Ultimately, lessons learned from echoes of the 1918 influenza pandemic, 2003 SARS epidemic, and 2014–2016 West African Ebola outbreak remind us “it [takes] patience, respectful dialogue and learning amongst both villagers, [educators] and health workers to … co-develop socially appropriate interventions” (Leach, 2020, para. 5). Furthermore, drawing on global outbreaks of decades past and paying mindful attention to the ways in which political responses unfold in response to COVID-19 are essential tasks for social scientists and education professionals to “inform efforts that are more sensitive, contextually attuned – and perhaps more likely to be effective” (Leach, 2020, para. 12).

Based on guidance from the CDC, advance planning, preparedness, and open dialogue are keys to public health communication, particularly with underserved minority and immigrant populations (Stern, Cetron, & Markel, 2009; Tsetsura & Kruckeberg, 2017). Only when trust and transparency are established with the populace—with especial regard to disseminating information through media (O’Malley, Rainford, & Thompson, 2009)—will public health officials, education officials, and political leaders have auspicious opportunities to improve collective decision making processes and resolve differences that are crucial to social, economic, and cultural equity amid global crises (Stern et al., 2009).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tiffany Karalis Noel: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Footnotes

Bellagio Principle 3: Planning and response should facilitate public involvement in surveillance and reporting of possible cases without fear of discrimination, reprisal or uncompensated loss of livelihood. Recognizing their vulnerability, special efforts are needed to foster reporting by disadvantaged groups, as well as to protect them from negative impacts which could worsen their situation (Bellagio Group, 2007).

References

- Aitken P. 2020, March 27. Asian Americans reported hundreds of racist acts in last week, data shows.https://www.foxnews.com/us/asian-americans-racist-acts-%20coronavirus Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Albright J. Welcome to the era of fake news. Media and Communication. 2017;5(2):87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Allport F.H., Lepkin M. Building war morale with news-headlines. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1943;7:211–221. doi: 10.1086/265615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew B. Media-generated shortcuts: Do newspaper headlines present another roadblock for low-information rationality? Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics. 2007;12(2):24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Asmelash L. 2020, February 2. UC Berkeley faces backlash after stating ’xenophobia’ is ’common’ or ’normal’ reaction to coronavirus.https://edition.cnn.com/2020/02/01/us/uc-berkeley-coronavirus-xenophobia-%20trnd/index.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Associated Press . 2020, May 17. US senator criticized for telling students China is to blame for Covid-19.https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/17/senator-%20ben-sasse-china-coronavirus-graduation-speech Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Baker D.L. Differential definitions of fear and forgiveness: The case of SARS in North America. International Journal of Public Administration. 2007;30(12–14):1641–1656. doi: 10.1080/01900690701465301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett R., Brown P.J. Stigma in the time of influenza: Social and institutional responses to pandemic emergencies. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197(1):S34–S37. doi: 10.1086/524986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellagio Group . 2007. Statement of principles.http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/bioethics/bellagio Available from: accessed 04 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee S. The CRAAP test. LOEX Quarterly. 2004;31(4) http://commons.emich.edu/loexquarterly/vol31/iss3/4 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2019, March 20. 1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus)https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-%20h1n1.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Y.U., Surjandy, Ernawaty . International conference on information management and technology (ICIMTech) 2017. Higher education student behaviors in spreading fake news on social media: A case of line group; pp. 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell B. 2020, June 1. Anti-racism protests versus COVID-19 risk: ’I wouldn’t weigh these crises separately’.https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-%20updates/2020/06/01/867200259/protests-over-racism-versus-risk-of-covid-i-wouldn-t-%20weigh-these-crises-separate Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Choi C., Jeung R., Kulkarni M. 2020. Stop AAPI hate reports (3/19/20-4/3/2020.https://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/stop-aapi-hate/ Available from: accessed 04 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cillizza C. 2020, March 20. Yes, of course Donald Trump is calling coronavirus the ’China virus’ for political reasons.https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/20/politics/donald-trump-china-virus-%20coronavirus/index.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy N.J., Rubin V.L., Chen Y. Automatic deception detection: Methods for finding fake news. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 2015;52(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Das M. Social construction of stigma and its implications – observations from COVID-19. Social Sciences and Humanities Open. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3599764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elder M. 2020, March 13. Fox news and Donald Trump are embracing xenophobia to defend against the coronavirus.https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/miriamelder/coronavirus-fox-news-trump-china Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Forgey Q. 2020. March 18). Trump on ’Chinese virus’ label: ’It’s not racist at all’.https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/18/trump-pandemic-drumbeat-coronavirus-%20135392 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Fung I.C.-H., Tse Z.T.H., Cheung C.-N., Miu A.S., Fu K.-W. Ebola and the social media. The Lancet. 2014;384(9961):2207. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber A.M. 2020, April 27. Planning for fall 2020.https://www.harvard.edu/coronavirus/updates-community-messages/planning-for-fall-%202020 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett L. 2020, May 30. Trump scapegoats China and WHO-and Americans will suffer.https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/30/trump-scapegoats-china-and-who-%20and-americans-will-suffer/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- de la Garza A. 2020. March 16). How social media is shaping our fears of the coronavirus.https://time.com/5802802/social-media-coronavirus/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Gay R. 2020, May 30. Remember, No one is coming to save us.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/30/opinion/sunday/trump-george-floyd-%20coronavirus.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor G.K. 2020, January 28. Coronavirus: Outrage over Chinese blogger eating bat soup sparks apology.https://www.foxnews.com/food-drink/coronavirus-%20chinese-blogger-eats-bat-soup Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Geer J.G., Kahn K.F. Grabbing attention: An experimental investigation of headlines during campaigns. Political Communication. 1993;10(2):175–191. doi: 10.1080/10584609.1993.9962974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstmann E. 2020, April 4. Irony: Hate crimes surge against asian Americans while they are on the front lines fighting COVID-19.https://www.forbes.com/sites/evangerstmann/2020/04/04/irony-hate-crimes-surge-%20against-asian-americans-while-they-are-on-the-front-lines-fighting-covid-%2019/#709816c73b70 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Han N. 2020, May 23. I don’t scare easily, but COVID-19 virus of hate has me terrified: Reporter’s Notebook.https://abcnews.go.com/US/asian-americans-covid-%2019-racism-virus-hate-reporters/story?id=70810109 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes S. 2020, March 6. As coronavirus spreads, so does xenophobia and racism.https://time.com/5797836/coronavirus-racism-stereotypes-attacks/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- He J., He L., Zhou W., Nie X., He M. Discrimination and social exclusion in the outbreak of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:2933. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe T. “Spanish flu”: When infectious disease names blur origins and stigmatize those infected. American Journal of Public Health. 2018;108(11):1462–1464. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan T. 2020, May 19. Asian American doctors and nurses are fighting racism and the coronavirus.https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/05/19/asian-american-discrimination/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Jeung R., Kulkarni M.P., Choi C. Op-Ed: Anti-Asian American hate crimes are surging. Trump is to blame. 2020, April 1. Retrieved April 6, 2020, from https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-04-01/coronavirus-anti-asian-%20discrimination-threats. [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. 2020, March 25. They just see that you’re Asian and you are horrible": How the pandemic is triggering racist attacks.https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/3/25/21190655/trump-coronavirus-racist-asian-%20americans Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Leach M. 2020. Echoes of Ebola: Social and political warnings for the COVID-19 response in african settings.http://somatosphere.net/forumpost/echoes-of-ebola/ Retrieved April 4, 2020, from Somatosphere website: [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Rogers W.A. Ethics, pandemic planning and communications. Monash Bioethics Review. 2006;25:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Rogers W.A., Braunack-Mayer A. Social justice and pandemic influenza planning: The role of communication strategies. Public Health Ethics. 2008;1(3):223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Liu E. 2020, April 11. Covid-19 has inflamed racism against Asian-Americans. Here’s how to fight back.https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/10/opinions/how-to-fight-bias-%20against-asian-americans-covid-19-liu/index.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Mastio D. 2020, March 11. No, calling the novel coronavirus the ’Wuhan virus’ is not racist.https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2020/03/11/sars-cov-2-chinese-%20coronavirus-isnt-racist-wuhan-covid-19-column/5020771002/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P., Rainford J., Thompson A. Transparency during public health emergencies: From rhetoric to reality. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87(8):614–618. doi: 10.2471/blt.08.056689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmet W.E., Rothstein M.A. The 1918 influenza pandemic: Lessons learned and not—introduction to the special section. American Journal of Public Health. 2018;108(11):1435–1436. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person B., Sy F., Holton K., Govert B., Liang A. Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004:358–363. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfau M.R. Covering urban unrest: The headline says it all. Journal of Urban Affairs. 1995;17(2):131–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9906.1995.tb00340.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips K. 2020, March 28. ’They look at me and think I’m some kind of virus’: What it’s like to be Asian during the coronavirus pandemic.https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/03/28/coronavirus-racism-asian-%20americans-report-fear-harassment-violence/2903745001/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Rayess M. El, Chebl C., Mhanna J., Hage R. Fake news judgement: The case of undergraduate students at Notre. Reference Services Review. 2018;46(1):146–149. doi: 10.1108/RSR-07-2017-0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Redden E. 2020, April 2. Scholars confront coronavirus-related racism in the classroom, in research and in community outreach. Retrieved April 6, 2020, from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/04/02/scholars-confront-coronavirus-related-%20racism-classroom-research-and-community. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K., Jakes L., Swanson A. 2020, March 18. Trump defends using ’Chinese virus’ label, ignoring growing criticism.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/us/politics/china-virus.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Rzymski P., Nowicki M. COVID-19-related prejudice toward asian medical students: A consequence of SARS-CoV-2 fears in Poland. J Infect Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.013. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer C., Schadauer A. Online fake news, hateful posts against refugees, and a surge in xenophobia and hate crimes in Austria. In: Dell’Orto G., Wetzstein I., editors. Refugee news, refugee politics: Journalism, public opinion and policymaking in Europe. Routledge; New York, NY: 2018. (Chapter 8) [Google Scholar]

- Shen-Berro J. 2020, March 18. Sen. Cornyn: China to blame for coronavirus, because ’people eat bats.https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/sen-cornyn-%20china-blame-coronavirus-because-people-eat-bats-n1163431 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K. 2019-nCoV, fake news, and racism. The Lancet. 2020;395(10225):685–686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30357-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman C. 2016. “This analysis shows how fake election news stories outperformed real news on Facebook”, BuzzFeed.https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/viral-fake-election-news-%20outperformed-real-news-on-facebook available at: accessed 6 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E.J., Fowler G.L. How comprehensible are newspaper headlines? Journalism Quarterly. 1982;59(2):305–308. doi: 10.1177/107769908205900219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stern A.M., Cetron M.S., Markel H. Closing the schools: Lessons from the 1918-19 U.S. Influenza pandemic. Health Affairs. 2009;28(6):W1066–W1078. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum P.H. The effect of headlines on the interpretation of news stories. Journalism Quarterly. 1953;30(2):189–197. doi: 10.1177/107769905303000206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taubenberger J.K., Reid A.H., Krafft A.E., Bijwaard K.E., Fanning T.G. Initial genetic characterization of the 1918 "Spanish" influenza virus. Science. 1997;275(5307):1793–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavernise S., Oppel R.A. 2020, March 23. Spit on, yelled at, attacked: Chinese- Americans fear for their safety.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/chinese-coronavirus-racist-attacks.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- The Learning Network . 2020, March 20. Film club: ’Coronavirus racism infected my high school.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/20/learning/film-club-%20coronavirus-racism-infected-my-high-school.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Tsetsura K., Kruckeberg D. Routledge; New York: 2017. Transparency, public relations and the mass media. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar S. Hot crises and media reassurance: A comparison of emerging diseases and Ebola Zaire. British Journal of Sociology. 1998;49(1):36–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/591262 [Google Scholar]

- Voytko L. 2020, May 31. America’s ’two deadly viruses’–racism and covid-19-go viral among outraged twitter users.https://www.forbes.com/sites/lisettevoytko/2020/05/31/americas-two-deadly-%20virusesracism-and-covid-19-go-viral-among-outraged-twitter-users/#31b1692c5ae3 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Waxler N. Learning to be a leper: A case study in the social construction of illness. In: Brown P.J., editor. Understanding and applying medical anthropology. Mayfield Publishing Company; California City, CA: 1981. pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- White T.P. 2020. CSU chancellor timothy P. White’s statement on fall 2020 university operational plans.https://www2.calstate.edu/csu-%20system/news/Pages/CSU-Chancellor-Timothy-P-Whites-Statement-on-Fall-2020-%20University-Operational-Plans.aspx May 12. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2010, November 5. WHO report on global surveillance of epidemic-prone infectious diseases - influenza.https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/CSR_ISR_2000_1/en/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2015, May 8. World health organization best practices for the naming of new human infectious diseases.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/163636/WHO_HSE_FOS_15.1_eng.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2020, June 2. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=CjwKCAjw8df2BRA3EiwAvfZWaIWMK2HW4cO5nss%20Avsca0Woc6IHZ5Ct1wrO5J-6ZIlRcOyBVFSyTyBoC-8cQAvD_BwE Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Yam K. 2020, March 16. Trump tweets about coronavirus using term ’Chinese Virus.https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/trump-tweets-about-%20coronavirus-using-term-chinese-virus-n1161161 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Chen N., Naresh D. 2020, February 21. What’s spreading faster than coronavirus in the US? Racist assaults and ignorant attacks against asians.https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/20/us/coronavirus-racist-attacks-against-asian-%20americans/index.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. 2020, April 21. How the coronavirus is surfacing America’s deep-seated anti-Asian biases.https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/4/21/21221007/anti-asian-%20racism-coronavirus Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Yu Y., Fang A. 2020, May 9. We are not COVID-19: Asian Americans speak out on racism.https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/We-are-not-%20COVID-19-Asian-Americans-speak-out-on-racism Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]