Highlights

-

•

MERS is characterized by fever, encephalopathy, and a reversible splenium lesion.

-

•

MERS has been associated with infection, potentially as an autoimmune response.

-

•

MERS has not previously been described in conjunction with COVID-19.

-

•

We present the first reported case of MERS in the setting of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Keywords: MERS, Mild encephalopathy with reversible splenium lesion, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2

Abstract

Neurological complications of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) are common, and novel manifestations are increasingly being recognized. Mild encephalopathy with reversible splenium lesion (MERS) is a syndrome that has been associated with viral infections, but not previously with COVID-19. In this report, we describe the case of a 69 year-old man who presented with fever and encephalopathy in the setting of a diffusion-restricting splenium lesion, initially mimicking an ischemic stroke. A comprehensive infectious workup revealed positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies, and a pro-inflammatory laboratory profile characteristic of COVID-19 infection. His symptoms resolved and the brain MRI findings completely normalized on repeat imaging, consistent with MERS. This case suggests that MERS may manifest as an autoimmune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and should be considered in a patient with evidence of recent COVID-19 infection and the characteristic MERS clinico-radiological syndrome.

1. Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, associated neurological complications are being increasingly described. According to an observational study from Wuhan, China, 36.4% of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 demonstrated neurological manifestations [1]. The virus has been linked to several different types of neurological complications, including hyposmia, hypogeusia, encephalitis, headache, neuropathy, and stroke [2]. It has been speculated that these manifestations may result from direct viral entry into the central nervous system via multiple mechanisms, such as retrograde neuronal migration and hematogenous spread [3]. Subsequent passage into neurons is likely mediated by binding to the cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is a known route of cellular entry by both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [4]. ACE2 is expressed throughout the brain, including in the brainstem, and viral involvement of the brainstem cardiorespiratory centers is thought to play a role in the severe respiratory symptoms experienced by many infected with SARS-CoV-2 [5]. In addition to direct neuronal invasion, neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection also result from an autoimmune response to the virus. SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with a severe inflammatory response in a subset of patients [6]. Additionally, it has been linked with neurological immune-mediated conditions such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy [7], [8], [9].

Mild encephalopathy with reversible splenium lesion (MERS) is a clinico-radiographical condition that is characterized by a reversible lesion isolated to the corpus collosum on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [10]. Patients with MERS typically present with fever and associated encephalopathy and lethargy [10]. Other neurological manifestations that have been reported are seizures and behavioral changes [10]. MERS has been associated with antiepileptic medication withdrawal, high-altitude exposure, and metabolic disturbances, but it is most commonly associated with infection [11]. Here, we describe the case of a patient with MERS and evidence of COVID-19 infection, which has not been previously reported.

2. Case presentation

A 69 year-old man with hypertension and recent visit to Nigeria presented to the hospital with acute-onset encephalopathy and high grade fever. His neurologic exam on presentation was significant for disorientation, inattention, and bradyphrenia without focal deficits.

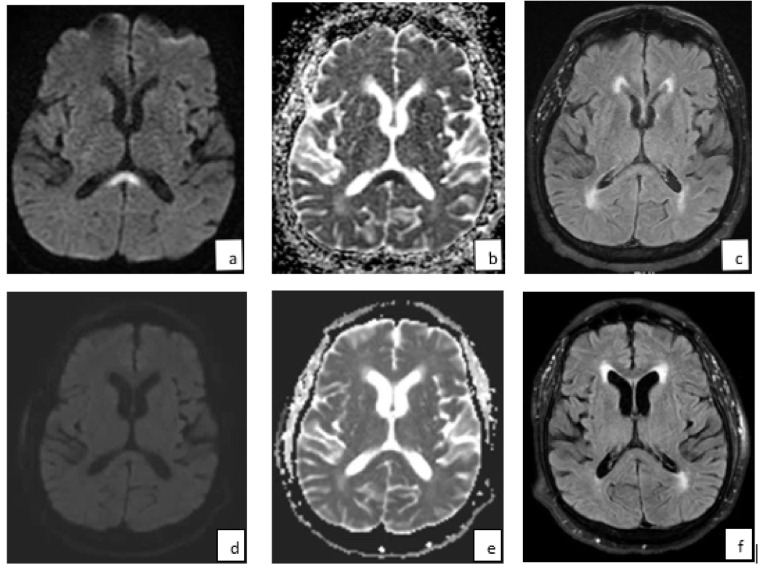

A metabolic and extensive infectious workup, including serological and CSF testing for pathogens associated with his recent travel, only revealed elevated SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG antibodies, suggesting recent exposure. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of nasopharyngeal samples for SARS-CoV-2 was negative. A lumbar puncture showed normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leukocyte count, protein, and glucose. He had significantly elevated systemic inflammatory markers, including elevated c-reactive protein (CRP) (50.32 mg/dL, ref <0.50), interleukin-6 (18.58 pg/mL, ref <5.00), fibrinogen (>1000 mg/dL, ref 173–430) and d-dimer levels (6.40 μg/mL, ref <0.50). Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed diffuse slowing. Brain MRI revealed a non-enhancing region of restricted diffusion and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Fig. 1 a–c). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck was unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed new-diagnosis heart failure, with an ejection fraction of <30%. He was treated with anticoagulation given concern for cardioembolism in the setting of heart failure and suspected prothrombotic state. His encephalopathy resolved over the course of two weeks. At that time, a repeat brain MRI showed complete resolution of the corpus callosum lesion (Fig. 1d–f), consistent with MERS.

Fig. 1.

A reversible splenium lesion on MRI in a patient with antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. Initial MRI brain showed a midline splenium increased signal on (a) DWI and (b) FLAIR, and decreased signal on (b) ADC sequences. After two weeks, there was complete reversal of these changes on (d) DWI, (e) ADC, and (f) FLAIR sequences.

3. Discussion

In this report, we present a case of mild encephalopathy with reversible splenium lesion in a patient with COVID-19 antibodies and a proinflammatory marker profile that has been associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection [12]. His clinical syndrome of fevers and encephalopathy in conjunction with a reversible midline splenium lesion on brain MRI, is characteristic of MERS [13]. Typical imaging features of the MERS defining lesion, as noted in this case, are high signal intensity on T2, FLAIR, and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences, decreased intensity on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, and no contrast enhancement (Fig. 1). This condition, more commonly seen in Asian populations and children, but also reported in other populations, has been associated with metabolic abnormalities, antiepileptic medications, but most frequently with infections such as influenza virus [13], [14]. Although the pathophysiologic mechanism underlying MERS is unknown, it is believed that intramyelinic edema and inflammation within the splenium may be the result of a spontaneously reversible autoimmune response, with complete resolution of clinical and radiographical abnormalities seen in most instances [14], [15].

In our case, such a response to SARS-CoV-2 is suggested by the presence of antibodies to this virus, a pro-inflammatory laboratory profile which has been associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, including elevated D-dimer, CRP, fibrinogen, and interleukin-6 levels [12], and the absence of other etiologies. This is the first case, to our knowledge, demonstrating that MERS can be a consequence of exposure to the virus. Although presumably an autoimmune response, such as has been recently recognized in other immune-mediated neurological complications of COVID-19 [7], [8], [9], the exact mechanism(s) by which MERS may result from SARS-CoV-2 are unknown and warrant future study.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we report a case of MERS in a patient with evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection. To our knowledge, this neurological complication has not been previously described in association with COVID-19. Given what is known about the pathophysiologic mechanism of MERS and the presence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in our patient, we propose that MERS may result from an autoimmune response to the virus. We suggest that MERS should be considered in a patient with encephalopathy and a diffusion-restricting, FLAIR hyperintense lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum in a patient with testing consistent with recent COVID-19 infection.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2019;2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Y., Xu X., Chen Z. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z., Liu T., Yang N. Neurological manifestations of patients with COVID-19: potential routes of SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion from the periphery to the brain [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 4] Front Med. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0786-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Z., Kang H., Li S., Zhao X. Understanding the neurotropic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2: from neurological manifestations of COVID-19 to potential neurotropic mechanisms [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 26] J Neurol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09929-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steardo L., Steardo L., Jr, Zorec R. Neuroinfection may contribute to pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 29] Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2020 doi: 10.1111/apha.13473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao X. COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:269–270. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedaghat Z., Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons T., Banks S., Bae C. COVID-19-associated acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 30] J Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09951-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poyiadji N., Shahin G., Noujaim D. COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 31] Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ka A., Britton P., Troedson C. Mild encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion: an important differential of encephalitis. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Monco J.C., Cortina I.E., Ferreira E. Reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES): What's in a name? J Neuroimaging. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2008.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connors J.M., Levy J.H. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020 doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan J., Yang S., Wang S. Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion (MERS) in adults-a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:103–111. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0875-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takanashi J., Barkovich A.J., Yamaguchi K. Influenza-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum: A case report and literature review. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(5):798–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y., Zheng J., Zhang L. Reversible splenial lesion syndrome associated with encephalitis/encephalopathy presenting with great clinical heterogeneity. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:49. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0572-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]