Abstract

Exposure to environmental contaminants early in life can have long lasting consequences for physiological function. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are a group of ubiquitous contaminants that perturb endocrine signaling and have been associated with altered immune function in children. In this study, we examined the effects of developmental exposure to PCBs on neuroimmune responses to an inflammatory challenge during adolescence. Sprague Dawley rat dams were exposed to a PCB mixture (Aroclor 1242, 1248, 1254, 1:1:1, 20 ug/kg/day) or oil control throughout pregnancy, and adolescent male and female offspring were injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 50 μg/kg, ip) or saline control prior to euthanasia. Gene expression profiling was conducted in the hypothalamus, prefrontal cortex, striatum, and midbrain. In the hypothalamus, PCBs increased expression of genes involved in neuroimmune function, including those within the nuclear factor kappa b (NF-κB) complex, independent of LPS challenge. PCB exposure also increased expression of receptors for dopamine, serotonin, and estrogen in this region. In contrast, in the prefrontal cortex, PCB exposure blunted or induced irregular neuroimmune gene expression responses to LPS challenge. Moreover, neither PCB nor LPS exposure altered expression of neurotransmitter receptors throughout the mesocorticolimbic circuit. Almost all effects were present in males but not females, in agreement with the idea that male neuroimmune cells are more sensitive to perturbation and emphasizing the importance of studying both male and female subjects. Given that altered neuroimmune signaling has been implicated in mental health and substance abuse disorders that often begin during adolescence, these results highlight neuroimmune processes as another mechanism by which early life PCBs can alter brain function later in life.

Keywords: endocrine disrupting compound, NF-κB, TLR4, Dopamine, estradiol

1. Introduction

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are environmental contaminants that were used in industry for decades before being banned in the United States in 1979 (Borja et al., 2005; Seegal, 2000; Tilson et al., 1990). However, they are still found in the environment and in tissues of virtually all humans due to their persistence and continued generation as an unintentional industrial byproduct (Borja et al., 2005; Dewailly et al., 1999; Seegal et al., 2011; Shain et al., 1991). In mammals, PCBs cross the placenta and are transferred from mother to infant during lactation (DeKoning and Karmaus, 2000; Grandjean et al., 1995; Heilmann et al., 2010; Tilson et al., 1990). This perinatal exposure can affect development of immune, endocrine, and nervous systems, and their interactions (Desaulniers et al., 2013; Weisglas-Kuperus, 1998).

The effects of PCBs on peripheral immune function are well-studied. In humans, PCB exposure has been linked to blunted adaptive immune responses in infants and children (Dewailly et al., 2000; Heilmann et al., 2010; Heilmann et al., 2006; Hochstenbach et al., 2012; Stolevik et al., 2013; Weisglas-Kuperus et al., 2000), and proinflammatory effects in adults (Perkins et al., 2016; Turunen et al., 2013). There are multiple potential mechanisms behind these effects, including production of reactive oxygen species and altered activity of the nuclear factor kappa b (NF-κB) complex (Abliz et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2010; Hennig et al., 2002; Kwon et al., 2002; Sipka et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2019), an important transcription factor for both inflammation and neural development and plasticity (Lawrence, 2009; O’Neill and Kaltschmidt, 1997). PCBs and their metabolites also disrupt steroid hormone activity (Abdelrahim et al., 2006; Bergeron et al., 1994; Grimm et al., 2015; Hamers et al., 2011; Layton et al., 2002; Matthews et al., 2007; Seegal et al., 2005; Takeuchi et al., 2017; Tavolari et al., 2006). For example, PCBs are known to act as both estrogen receptor agonists and antagonists (Gore et al., 2015; Hamers et al., 2011) which could indirectly alter immune function due to estrogen’s complex but generally immunosuppressive properties (Bellavance and Rivest, 2012; Bruce-Keller et al., 2000; Klein and Flanagan, 2016; Loram et al., 2012; Villa et al., 2016). Given that most mechanistic studies of PCBs on immune function were performed in cell lines or only in male animals, continued investigation on the effects of PCBs on immune function in both males and females is warranted.

Far less is known about neuroimmune effects of PCBs. We previously reported effects of prenatal PCB exposure on the neuroimmune system of neonatal male and female rats (Bell et al., 2018), and (Hayley et al., 2011) described effects of PCBs on brain cytokines in adult females. Epidemiological and laboratory research studies have demonstrated that PCBs can induce neuronal dysfunction and death, especially of dopaminergic and serotonergic cells (Bell et al., 2018; Boix and Cauli, 2012; Dervola et al., 2015; Enayah et al., 2018; Kodavanti, 2006; Pessah et al., 2010; Pessah et al., 2019; Seegal et al., 1988; Seegal et al., 2002; Tilson et al., 1998). Dopamine and serotonin interact with neuroimmune systems in multiple ways. For example, neuroinflammation is associated with excitotoxicity, dopaminergic cell dysfunction and death, and altered serotonin metabolism and handling (Capuron et al., 2012; Dantzer, 2018; Felger et al., 2007; Felger et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2007; Robson et al., 2017). Conversely, dopamine, has anti-inflammatory effects (Sarkar et al., 2010; Shao et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2015) while serotonin has been shown to both inhibit and potentiate neuroimmune cell function (Glebov et al., 2015; Ledo et al., 2016).

Neuroimmune systems are especially important during development, influencing sexual differentiation of the hypothalamus perinatally, glutamatergic synapses in the prefrontal cortex during adolescence, and dopaminergic synapses in the nucleus accumbens during adolescence, (Kopec et al., 2018; Lenz et al., 2013; Mallya et al., 2018; Nissen, 2017; Schafer et al., 2012). Thus, disruption of neuroimmune function during development has been proposed as a factor prevalence of autism spectrum disorder, depression, schizophrenia, neurocognitive deficits, substance abuse, and later neurodegeneration in humans (Brenhouse and Schwarz, 2016; Greene et al., 2019; Hanamsagar et al., 2017; Hoops and Flores, 2017; Marín, 2016). Adolescence is also concurrent with the pubertal increase in gonadal hormones, thus making it a period of great interest (Brenhouse and Schwarz, 2016; Walker et al., 2017).

For all the above reasons, in this study we tested the hypothesis that developmental exposure to PCBs would alter basal and stimulated neuroimmune function and dopaminergic, serotonergic, and gonadal hormone signaling during adolescence in sex-specific ways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental design

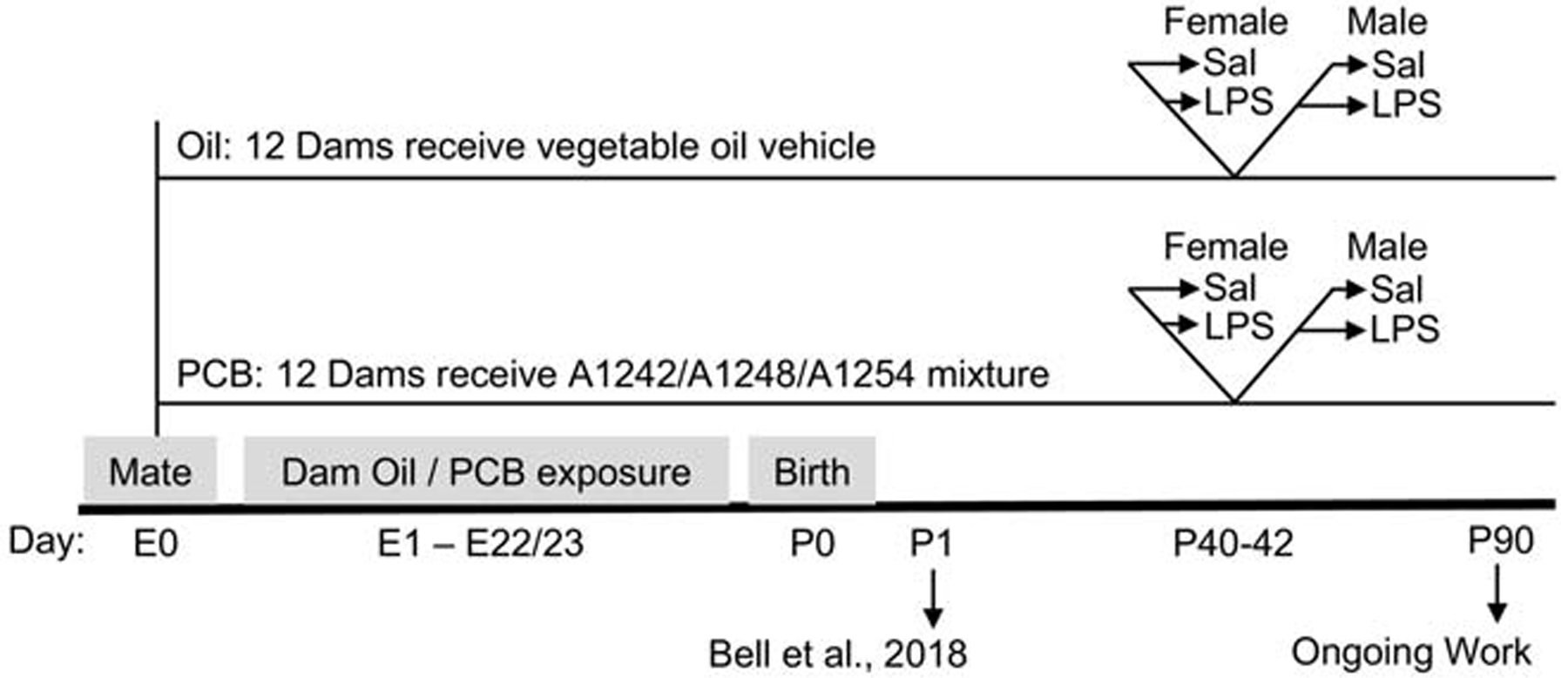

Pregnant Sprague Dawley rats were treated with either an oil control or PCB mixture throughout their pregnancy until parturition. In adolescence, one male and one female from each litter were injected with either saline or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to provide an inflammatory challenge prior to euthanasia and tissue collection. Thus, this study uses a two (oil or PCB perinatal exposure) by two (sal or LPS adolescent challenge) design within each sex (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Experimental timeline.

Pregnant dams were orally exposed to PCBs or oil control, throughout gestation (embryonic day E1 – E22/23). The day after birth (P1), up to four pups per litter were used for a previous study (Bell et al 2018), and then the litter was culled to four male and four female pups. Per litter, two males and two females were randomly assigned for use during adolescence (current study) or during adulthood (in a companion study, data not shown). Between P40–42, one male and one female were randomly assigned to receive an immune challenge (lipopolysaccharide, LPS, 50 ug/kg, i.p.) or saline vehicle control 2.5 hours prior to tissue collection.

2.2. Animals and husbandry

All animal protocols were approved by The University of Texas at Austin’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and done in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010). Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Houston, Texas) and were housed in a temperature-controlled room (21–23 °C) with a 12 hour light/dark cycle with lights off at 2:00 pm. Rats were housed (2–3 animals per cage) in polycarbonate cages (43 × 21 × 25 cm) with aspen bedding (PJ Murphy Forest Products, Sani-Chip). Cages were changed weekly and were provided with a 5–10 cm long section of PVC pipe for habitat enrichment. Animals received a low phytoestrogen, fishmeal-free Global Diet (Harlan-Teklad 2019, Indianapolis, Indiana) and water from glass bottles and metal sippers ad libitum. Rats were acclimated to the laboratory through daily handling for at least two weeks prior to mating.

Virgin females (3–4 months old) were paired overnight with untreated male rats (~6 months old). Each male sired one litter that was treated with the oil vehicle and one with PCBs. Successful mating was determined via a sperm-positive vaginal smear, after which dams were singly housed, randomly assigned to treatment group in a counterbalanced design, and began receiving oil (n=12) or PCB (n=12) treatment as described below. Dams were provided nesting materials several days before the expected day of birth, postnatal day (P) 0, and oil/PCB treatment stopped the morning pups were observed. On P1, pups were weighed and individually identified with a black Sharpie brand permanent marker. In each litter, up to four pups were randomly assigned to provide P1 tissue in a companion study (Bell et al 2018); if necessary, other randomly chosen pups were then culled such that litters had 6–8 pups with equal sex ratios beginning on P1.

From P7 on, pups were weighed, relabeled for identification, and handled (>5 minutes) weekly. On P21, pups were weaned and housed with same-sex littermates (2–3 animals per cage). Animals were monitored daily for age at eye opening and puberty onset (vaginal opening or preputial separation). On P40–42, up to four randomly assigned pups per litter (one male and one female each exposed to saline or LPS) were used for adolescent tissue. The remaining offspring were monitored for body weight until adulthood for use in an ongoing study. Twenty-four total litters were split across three cohorts, separated by 1–8 months, and PCB treatment was evenly represented across the cohorts. Cohort did not affect expression of genes significantly altered by PCBs or LPS when tested as a fixed variable or covariate. The experimenters were blind to treatment throughout the duration of the experiment.

2.3. Treatments

A 1:1:1 ratio of Aroclor 1242, 1248, and 1254 was used as described in Bell et al 2018. This mixture is predominately composed of non-coplanar congeners with 2–6 chlorine substitutions and was chosen to mimic the broad range of congeners present in the environment (Frame et al., 1996; Hites et al., 2004; Kostyniak et al., 2005). Aroclors were purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, Connecticut) with the following identification numbers: C-242-N-50MG, Lot# 01141, CAS# 53469-21-9; C-248 N-50MG, Lot# F-110, CAS# 12672- 29-6; C-254 N-50MG, Lot# 5428, CAS# 11097-69-1. PCBs were handled with necessary personal protective equipment in a chemical fume hood, and chemical and animal waste was disposed of with the Environmental Health and Safety office on campus.

The PCB mixture or Crisco vegetable oil vehicle was fed to the dams to mimic naturalistic exposure routes by applying approximately 100 ul of oil or PCB to a quarter of a palatable wafer (‘Nilla Wafer, Nabisco, ~0.9 g), with the volume adjusted such that dams were exposed daily to 20 ug/kg body weight. This dose was chosen to provide an exposure similar to that of infants in heavily exposed human populations. This was estimated using a) measures of PCBs in human breast milk, adipose tissue, and maternal to infant transmission (DeKoning and Karmaus, 2000; Dewailly et al., 1999; Grandjean et al., 1995; Lanting et al., 1998; Stellman et al., 1998) and b) relationships between exposure dose and resulting body burden in rats, both in adult males and in maternal transmittance to offspring (Hany et al., 1999; Kodavanti et al., 1998). Dams were fed the treated wafers every weekday morning beginning on the day that a sperm-positive vaginal smear was detected, until the day of parturition, in the second half of their light phase. Animals were habituated to taking the wafer in advanced and were watched to confirm that the entire wafer was consumed. While the dams were only treated with PCBs while pregnant, pups were exposed via placental and lactational transfer until weaning (Takagi et al., 1986; Takagi et al., 1976).

LPS was used to stimulate a temporary and non-infectious inflammatory reaction (E. coli 0111:B4, Sigma, L4391, Lot 014M4019V). Between P40–42, animals were injected with LPS (50 μg/kg, ip) or sterile saline vehicle and immediately returned to their home cage. They were scored for sickness behaviors (piloerection, lethargy, and ptosis) on a 0–3 scale as in (Kentner et al., 2006) two hours after injection and sickness behaviors were summed for analysis (max of 9).

2.4. Tissue collection

Animals were euthanized on P40–42, 2.5 hours after the LPS injection, in the first half of their dark phase. This chronological age was chosen to be mid-adolescent, a time when hormone-dependent and independent maturational processes occur in the brain. Males and females are at slightly different developmental phases at this age: females have completed vaginal opening whereas males have not yet completed preputial separation. Animals were kept in their home cage until just prior to rapid decapitation in an adjacent room. Brains were quickly removed from the skull, chilled on ice, and sectioned coronally using a rat brain matrix into 1 or 2 mm sections. From these sections, prefrontal cortex, striatum, hypothalamus, and midbrain were dissected out with razor blades and transferred into individual RNase-free microcentrifuge tubes, quickly frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Trunk blood samples were collected and allowed to clot for 30 min before centrifugation (1500 x g for 5 min). Sera were collected and stored at −80°C until use. Adrenals and gonads were also dissected out and weighed to indicate gross organ function. Females were of different stages of their estrous cycles at time of tissue collection, according to postmortem vaginal cytology: proestrus (10–20%), estrus (10–30%), or diestrus (50–60%). These stages were equally represented across oil/PCB and sal/LPS groups.

2.5. RNA isolation and gene expression quantification

RNA from the hypothalamus, prefrontal cortex, and striatum were extracted as previously described (Bell et al., 2018) with Qiagen mini RNeasy or Invitrogen Purelink kit protocols and treated with associated DNase while on the column, per manufacturer’s directions. RNA was extracted from midbrain samples using TRIzol™ (Cat # 15596026) according to manufacturer’s directions and treated with TURBO™ DNase upon isolation (Cat # AM2238). The RNA yield was determined using a NanoDrop™ Spectrophotometer, and RNA quality was assessed by randomly selecting approximately 10% of the samples to run on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies); all tested samples had RNA integrity numbers of 9 and above. Isolated RNA samples (200 ng) were reverse transcribed to cDNA using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcriptase kit with RNase inhibitor (Cat # 4374967), according to manufacturer’s protocol. Negative controls that did not receive reverse transcriptase during the cDNA conversion did not amplify during qPCR.

We initially focused on the hypothalamus because it is a hormone sensitive region that has an intrinsic dopaminergic cell population and is essential in regulating pyrogenic responses to pathogens. Here, 48 genes were selected for initial analysis, including those related to neuroimmune, hormone, and neuromodulator signaling (Table 1). Custom designed microfluidic Taqman Low Density Array (TLDA) cards (Applied Biosystems, Cat No 4342253) were used with Taqman Gene Expression Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Cat No 4369016) according to manufacturer’s directions; procedures were completed in consultation with the MIQE guidelines (Bustin et al., 2009) and gene assay details are included in (Bell et al., 2018). The samples were run at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 1 min using a ViiA 7 qPCR system (Applied Biosystems), which automatically determined the quantification cycle (Cq) of each sample. Gapdh, Rpl3a, and 18s were included and their geometric mean was used to normalize sample Cq values to calculate the relative expression of target genes to same sex oil- and saline-control groups, as in (Bell et al., 2018). Four of 70 samples, each from different groups, were identified by a Grubbs test as within-group outliers in more than four genes; they were removed from analysis for all 48 genes.

Table 1.

Summary of effects of PCB exposure and/or LPS challenge on adolescent hypothalamic gene expression.

| Gene | Effect of | Females | Males | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB | LPS | PCB | LPS | ||

| Xenobiotic signaling | |||||

| AhR | aryl hydrocarbon receptor | ||||

| Arnt | aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator | ||||

| Neuroimmune signaling | |||||

| Ccl22 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 22 | Sal < LPS ** | Sal < LPS ** | ||

| Cxcl9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | Sal < LPS ** | Sal < LPS ** | ||

| Cybb | cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide | ||||

| Ifna1 | interferon-alpha 1 | ||||

| Ikbkb | inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase beta | Oil < PCB * | |||

| Il1a | interleukin 1 alpha | Sal > LPS ** | Sal > LPS ** | ||

| Il1b | interleukin 1 beta | Sal < LPS ** | Sal < LPS ** | ||

| Il7r | interleukin 7 receptor | Sal < LPS * | Sal < LPS * | ||

| Itgam | integrin, alpha M | Oil < PCB * | |||

| Itgb2 | integrin, beta 2 | ||||

| Myd88 | myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 | Sal < LPS ** | |||

| Nfkb1 | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 | Sal < LPS * | Oil < PCB * | Sal < LPS * | |

| Ptgs2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | Sal < LPS ** | Sal < LPS ** | ||

| Ptges | prostaglandin E synthase | Sal < LPS ** | Sal < LPS ** | ||

| Rela | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A (avian) | Oil < PCB * | Sal < LPS ** | ||

| Tlr4 | toll-like receptor 4 | ||||

| Tnf | tumor necrosis factor | Sal < LPS ** | |||

| Neuroimmune modulators | |||||

| Arrb1 | arrestin, beta 1 | ||||

| Map3k7 | mitogen activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7 | ||||

| Tgfb2 | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | Oil < PCB * | |||

| Hormones, enzymes, and receptors | |||||

| Ar | androgen receptor | ||||

| Crh | corticotropin releasing hormone | ||||

| Cyp19a1 | cytochrome P450, family 19, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 (aromatase) | ||||

| Esr1 | estrogen receptor 1 | ||||

| Esr2 | estrogen receptor 2 | Oil < PCB ** | Sal < LPS * | ||

| Opioid precursors and receptors | |||||

| Oprk1 | opioid receptor, kappa 1 | Sal < LPS * | |||

| Oprm1 | opioid receptor, mu 1 | Sal < LPS * | |||

| Pdyn | prodynorphin | ||||

| Pomc | proopiomelanocortin | ||||

| Dopamine enzymes, receptors, and transporters | |||||

| Drd1a | dopamine receptor D1A | Oil < PCB ** | |||

| Drd2 | dopamine receptor D2 | Oil < PCB ** | |||

| Th | tyrosine hydroxylase | ||||

| Slc6a3 | solute carrier family 6, member 3 (dopamine transporter) | ||||

| Serotonin enzymes, receptors, and transporters | |||||

| Htr1a | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A | ||||

| Htr2a | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A | Oil < PCB ** | |||

| Tph1 | tryptophan hydroxylase 1 | ||||

| Slc6a4 | solute carrier, family 6, member 4 (serotonin transporter) | ||||

Significant effects (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01) are noted within each sex.

When indicated by hypothalamic results and preliminary data from unpublished studies, additional targets were quantified and run independently in the prefrontal cortex (Ikbkb, Nfkb1, Rela, Tlr4, Drd1, Drd2), striatum (Drd1, Drd2, Tlr4), and midbrain (Drd1, Drd2, Th, Tlr4) to determine region-specific effects. Taqman Gene Expression Mastermix (Part No 4369016) and similar parameters were used on a QuantStudio 6 qPCR system and Gapdh was used to normalize sample Cq. One sample was an outlier in all of the prefrontal cortex analysis and so was removed.

2.6. Serum corticosterone quantification

Total serum corticosterone was determined via a radioimmunoassay (ImmuChem Double Antibody 125I RIA Kit, MP Biomedicals LLC, Orangeburg NY). Samples were run across two assays in duplicate, according to manufacturer directions. Intra-assay CV was 1.99% and inter-assay CV of standards was 11.65%; minimum level of detection was 7.7 ng/ml. Two outliers from two different groups were identified via Grubb’s test and so were removed.

2.7. Serum cytokine quantification

Serum samples were thawed on ice and diluted in assay buffer. The Milliplex Cytokine / Chemokine Hormone assay (RECYTMAG-65K, Cat No) was run according to manufacturer directions. This assay contains interleukin (IL)- 1a, 1b, 4, 6, 10, interferon gamma (IFNγ), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF, also known as TNFα), which were selected based on literature and availability in the assay. Samples (25 μl) were run in duplicate across two plates and experimental groups were represented evenly between plates. Fewer than 30% of the samples within each group were above limits of detection for IFNγ and IL4 and were not analyzed further. Variability (%CV) of sample replicates within an assay and quality control values between assays were as follows, respectively: IL1a (15%, 19%), IL1b (13%, 18%), IL6 (12%, 3%), IL10 (11%, 11%), and TNF (10%, 7%). Three animals were removed from all assays because their replicate % CV values were unusually high. Limits of detection for IL1a, IL1b, IL6, IL10, and TNF were 45, 10.79, 235, 4.18, and 5.29 ng/ul, respectively.

2.8. Analysis and statistics

Effects and interactions between PCB exposure and LPS challenge (2×2 design) were determined within males and females independently because of known sex differences in neuroimmune outcomes. Each PCB or oil exposed litter provided no more than one animal per male/female, sal/LPS group, and individual animal was the unit of analysis. Number of adolescent pups collected per group were as follows: female oil-sal (n=9); female oil-LPS (n=9); female PCB-sal (n=9); female PCB-LPS (n=8); male oil-sal (n=8); male oil-LPS (n=9); male PCB-sal (n=9); male PCB-LPS (n=9). Grubbs tests were used to identify outliers within each group (described above) prior to analysis using SPSS and GraphPad Prism, with final ns and significant differences shown in figures and tables as *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01.

Body weight was analyzed with a repeated measures analysis of variance tests (ANOVA), with age as a within-subject variable and PCB treatment as the between-subject variable; follow-up t-tests were performed within an age. Age at eye opening, vaginal opening, and preputial separation were analyzed with t-tests to determine effects of PCB exposure prior to any LPS challenge. Relative expression of genes and concentrations of serum corticosterone were analyzed using two-way ANOVA to determine main effects of PCB exposure and LPS challenge, and any interactions between these two variables. Any significant interaction effects were followed-up by independent t-tests: effects of PCB within saline-control and LPS-challenged groups, and effects of LPS within oil-control and PCB-treated groups, were determined within each sex. Any groups that failed to meet parametric assumptions by failing Levene’s test were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U-test (MW), including Ptgs2, Crh, Cybb, and Ptges for both sexes, Tnf and Map3k7 in females, and Arrb1, Ar, and Htr1a in males. Serum cytokine values also did not meet parametric assumptions and were analyzed with a Mann-Whitney U-test.

For six genes (Il1b, Slc6a4, Ifna1, Tph1, Ccl22, and Cxcl9), at least one group had fewer than 30% of its samples fail to amplify (defined as Cq > 35) or reach detectable levels. As such, differences in the percent of samples that amplified within a group were identified with a χ2 goodness of fit test. Effects of PCB within saline-control and LPS-challenged groups, and effects of LPS within oil-control and PCB-treated groups, were determined within each sex to identify effects that are analogous to main effects of each treatment, or an interaction when the effect of one variable depended on the level of the other. Cqs for Cyp1a1, Ido1, Il4, Il6, and O3far1 were all either above 35 or undetermined and could not be analyzed further.

3. Results

3.1. Physiological development

When analyzed with age as a repeated measure, PCB exposure was associated with greater body weight in males (F(1,33) = 4.27, p < 0.05), independent of PCB exposure x age interactions. However, when follow-up t-tests were performed at each age, significant effects were only present from P28–35 in males, who were 5–10% heavier when PCB-exposed throughout this period (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Male animals exposed to PCBs had significantly greater body weights.

This effect was present from P28 – 35. Data are presented as mean body weight values ± SEM across time, and data for P28 are shown in the top left inset. Final n per group are shown within insert bar graph and represent final group counts for all days analyzed. Significant effects (p < 0.05) are noted (*).

PCBs also advanced the age at eye opening by approximately half a day, in both females (MW, p < 0.01, age at eye opening for oil: 15.31 days, PCB: 14.94) and males (F(68) = 8.83, p < 0.01, oil: 15.47, PCB: 14.97). This effect was no longer significant when the age at eye opening was normalized to body weight at P14. No significant effects of PCBs on age at pubertal onset, adrenal or gonad weight (relative to body weight), and sickness behavior responses to LPS were observed. As expected, summed sickness behavior was increased by LPS challenge in both females (MW, p < 0.01, from 0.22 to 1.76) and males (MW, p < 0.01, from 0.06 to 2.55), but this was not significantly altered by PCB exposure.

3.2. Gene expression in the hypothalamus

The effects of PCB exposure and LPS challenge on relative expression of 48 genes were analyzed in the hypothalamus (Table 1).

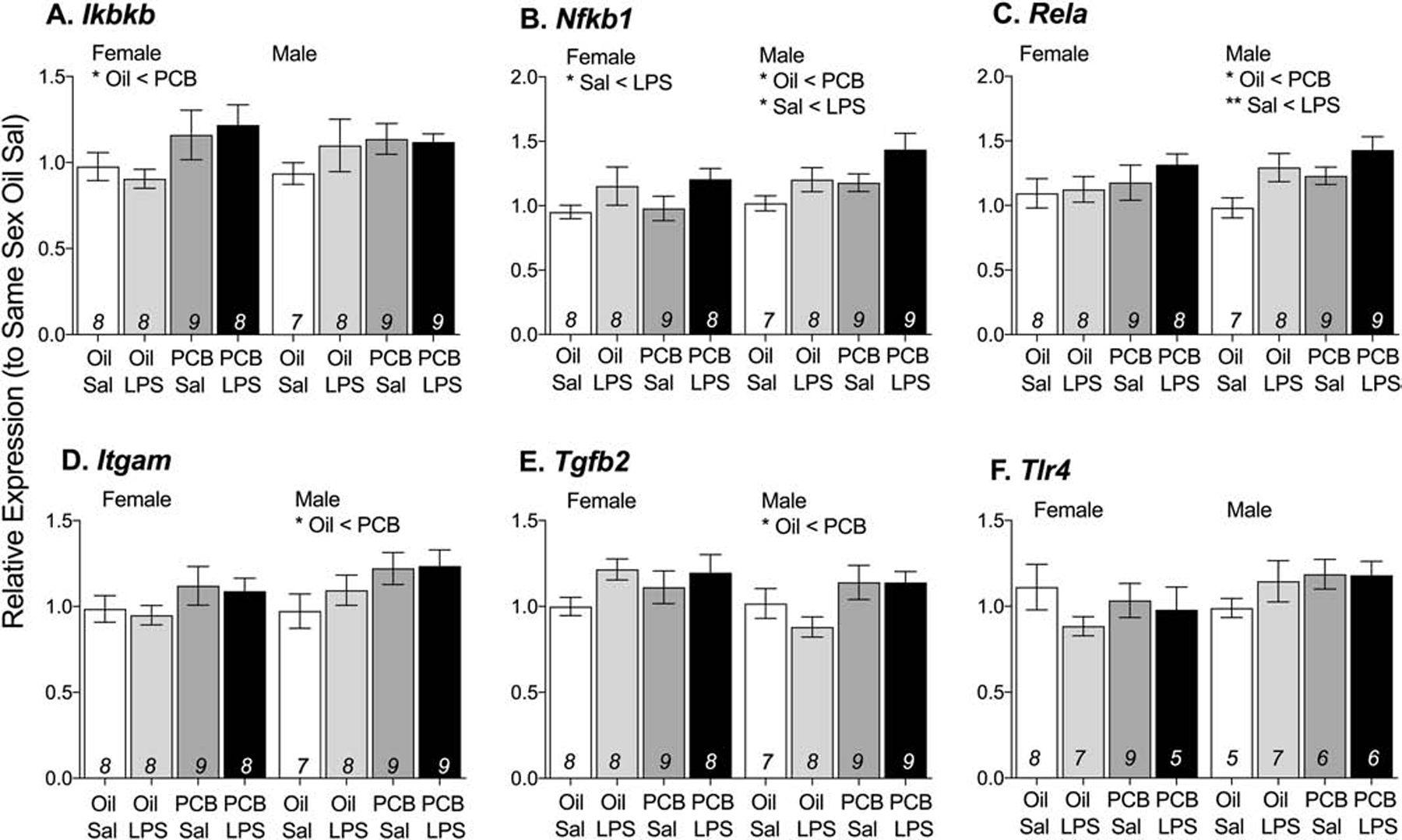

In the hypothalamus, all effects of PCBs were sex-specific and independent of LPS exposure. Animals exposed to PCBs had greater expression of five immune-signaling genes compared to those exposed to oil (Figure 3A–E). These genes included Ikbkb (F(1,29) = 5.23, p < 0.05) in females and Rela (F(1,29) = 4.37, p < 0.05), Nfkb1 (F(1,29) = 4.35, p < 0.05), Itgam (F(1,29) = 4.24, p < 0.05), and Tgfb2 (F(1,29) = 5.66, p < 0.05) in males. In both sexes, exposure to PCBs had no effect on the relative expression of Tlr4 in the hypothalamus (Figure 3F). Independent of PCB exposure, LPS increased expression of Nfkb1 (F(1,30) = 5.08, p < 0.05) in females (Figure 3B), and of Nfkb1 (F(1,30) = 5.09, p < 0.05) and Rela (F(1,30) = 8.28, p < 0.01) in males (Figure 3B–C).

Figure 3: Animals exposed to PCBs had greater expression of immune-related genes in the hypothalamus.

In response to PCB exposure, females had greater expression of Ikbkb (A) and males had greater expression of Rela (B), Nfkb1 (C), Itgam (D), and Tgfb2 (E). In both sexes, PCB exposure did not affect the relative expression of Tlr4. LPS also increased expression of Nfkb1 (B) and Rela (C) Data are presented as mean values ± SEM with final n per group, after removing outliers and samples that failed to amplify, shown within bars. Significant effects (*p < 0.05) are noted within sex.

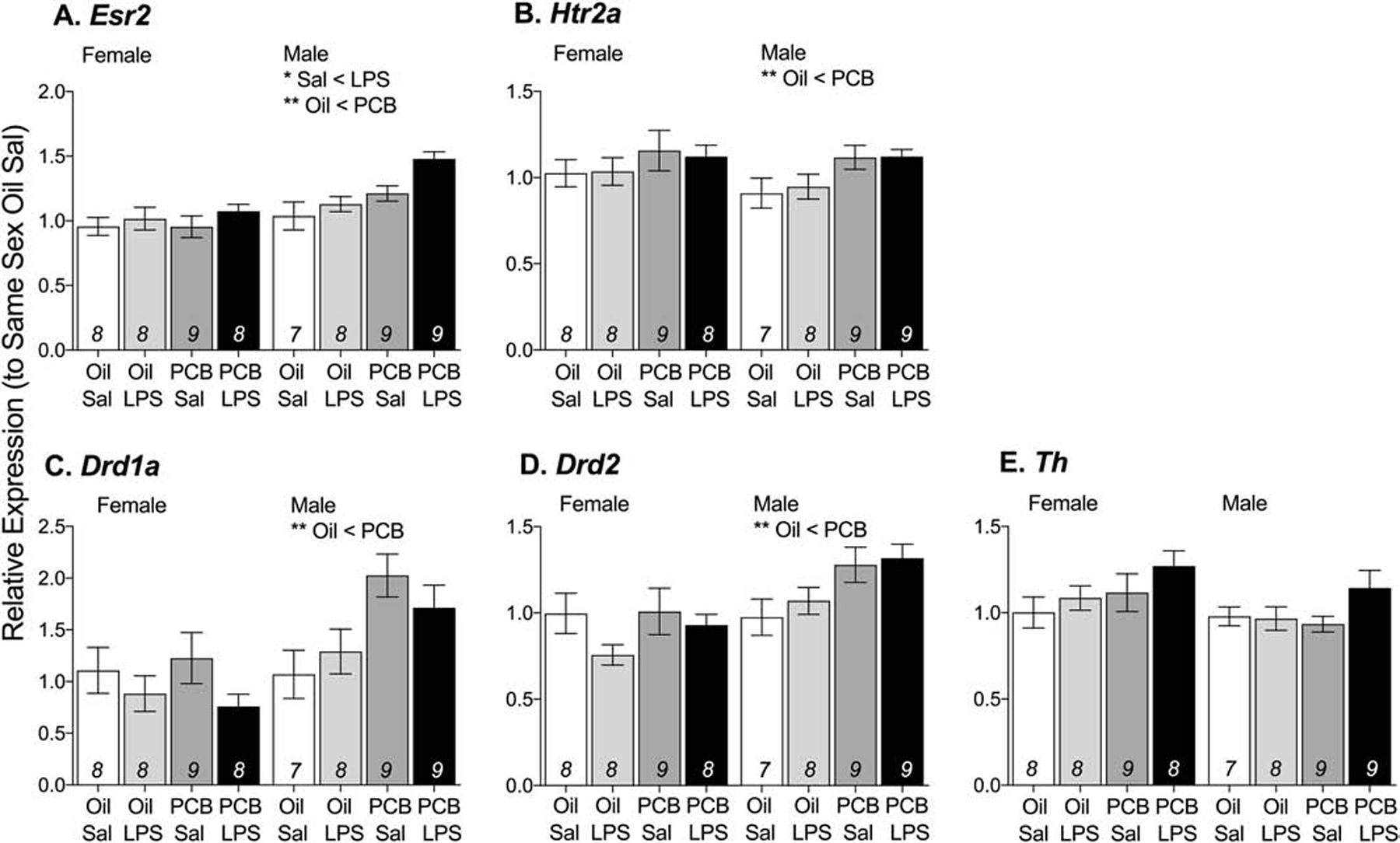

PCB exposure also altered neuromodulating endpoints in the hypothalamus. Males exposed to PCBs had greater expression of four receptors (Figure 4A–D): Esr2 (F(1,29) = 14.28, p < 0.01), Htr2a (F(1,29) = 8.03, p < 0.01), Drd1a (F(1,29) = 9.82, p < 0.01) and Drd2 (F(1,29) = 8.80, p < 0.01) but PCBs did not alter the relative expression of the rate limiting enzyme in catecholamine production, Th (Figure 4E). Males challenged with LPS also had increased expression of Esr2 (F(1,30) = 5.72, p < 0.05, Figure 4A).

Figure 4: Males exposed to PCBs had greater expression of neuromodulator receptors in the hypothalamus.

In response to PCB exposure, males had greater expression of Esr2 (A), Htr2a (B), Drdla (C), and Drd2 (D). In both sexes, PCB exposure did not change the relative expression of Th. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM with final n per group, after removing outliers and samples that failed to amplify, shown within bars. Significant effects (**p < 0.01) are noted within sex.

LPS also altered hypothalamic expression of several genes related to inflammation, independent of PCB exposure. Data are shown collapsed across oil and PCB groups (Table 2). In both males and females, those challenged with LPS had lower expression of Il1a and greater expression of Il7r, Nfkb1, Ptgs2, and Ptges than saline exposed animals. In addition, LPS-challenged females had greater relative expression of Oprk1 than saline controls. LPS-challenged males had greater relative expression of Esr2, Myd88, Oprm1, Rela and Tnf than saline controls. LPS also altered the proportion of samples that were reliably quantified via qPCR (Cq < 35), as determined by χ2 analysis: LPS exposure increased amplification of Ccl22, Cxcl9, and Il1b in both males and females.

Table 2:

LPS exposure altered expression of immune and neuromodulator receptor expression in the hypothalamus, independent of PCB exposure.

| Gene | Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sal | LPS | Statistics | Sal | LPS | Statistics | |

| Ccl22 | 0% | 81.25% | ** χ2 (1) = 22.79 | 0% | 87.50 % | ** χ2 (1) = 25.84 |

| Cxcl9 | 5.88 % | 93.75 % | ** χ2 (1) = 25.48 | 5.88 % | 93.75 % | ** χ2 (1) = 25.48 |

| Esr2 | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | ns, F(1,29) = 1.43 | 1.14 ± 0.06 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | * F(1,29) = 6.68 |

| Il1a | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | ** F(1,29) = 15.62 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | ** F(1,28) = 12.00 |

| Il1b | 11.76% | 81.25% | ** χ2 (1) = 16.05 | 11.76% | 93.75 % | ** χ2 (1) = 22.18 |

| Il7r | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 1.37 ± 0.09 | * F(1,29) = 6.76 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 1.22 ± 0.07 | * F(1,29) = 6.65 |

| Myd88 | 1.05 ± 0.07 | 1.20 ± 0.06 | ns, F(1,29) = 2.90 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.05 | ** F(1,29) = 8.16 |

| Nfkb1 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | 1.18 ± 0.08 | * F(1,29) = 4.49 | 1.11 ± 0.05 | 1.33 ± 0.08 | * F(1,29) = 5.41 |

| Oprk1 | 0.97 ± 0.06 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | * F(1,29) = 5.31 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.17 ± 0.06 | ns, F(1,29) = 2.42 |

| Oprm1 | 1.05 ± 0.06 | 1.14 ± 0.05 | ns, F(1,29) = 1.36 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 1.09 ± 0.04 | * F(1,29) = 4.36 |

| Ptgs2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | ** MW | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | ** MW |

| Ptges | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | ** MW | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 10 ± 1 | ** MW |

| Rela | 1.14 ± 0.09 | 1.22 ± 0.07 | F(1,29) = 0.58 | 1.12 ± 0.06 | 1.37 ± 0.07 | ** F(1,29) = 7.74 |

| Tnf | 1.0 ± O.I | 1.8 ± 0.2 | ns, MW | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | ** F(1,29) = 8.54 |

Data are shown mean ± SEM and were analyzed via a two-way ANOVA (main effect of LPS shown) or Mann-Whitney non-parametric test, or on the percent of samples that amplified (CT < 35) with a χ2 non-parametric test (collapsed across oil and PCB groups).

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01 are noted within sex

3.3. Gene expression in the mesocorticolimbic regions

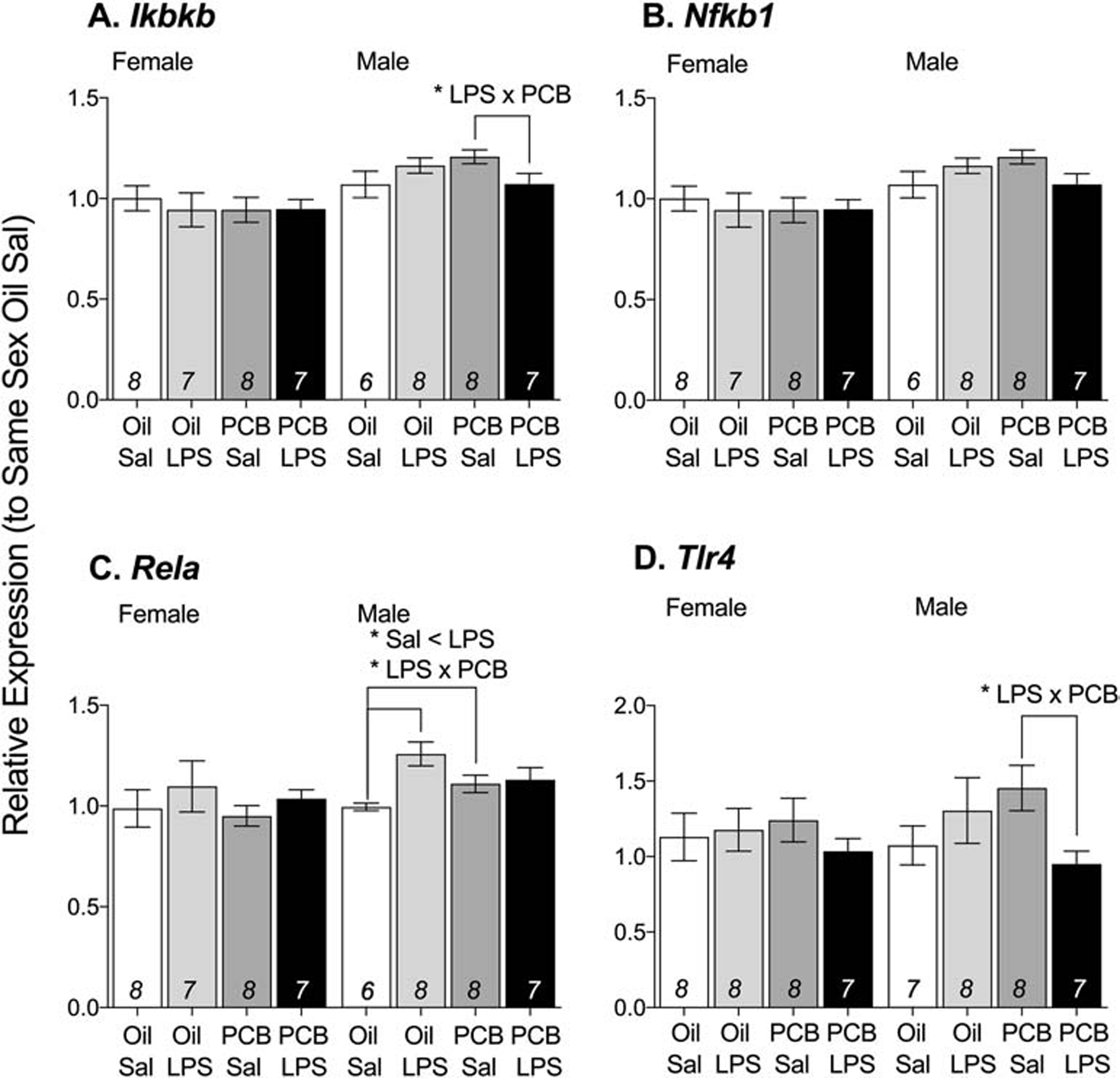

To follow up on effects of PCBs in the hypothalamus, genes associated with the NF-κB complex were analyzed in the prefrontal cortex, and Tlr4 and dopaminergic genes were analyzed throughout the mesocorticolimbic region (Table 3).

Table 3:

Summary of effects of PCB exposure and/or LPS challenge on adolescent mesocorticolimbic gene expression.

| Brain region | Gene | Effect of | Females | Males | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCB | LPS | PCB | LPSs | |||

| Prefrontal Cortex | ||||||

| Neuroimmune signaling | Ikbkb | inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase beta | LPS X PCB * | |||

| Nfkb1 | nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 | |||||

| Rela | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A (avian) | LPS X PCB *, Sal < LPS * | ||||

| Tlr4 | toll-like receptor 4 | LPS X PCB * | ||||

| Dopamine receptors | Drd1a | dopamine receptor D1A | ||||

| Drd2 | dopamine receptor D2 | |||||

| Stria turn | ||||||

| Neuroimmune signaling | Tlr4 | toll-like receptor 4 | ||||

| Dopamine receptors | Drd1a | dopamine receptor D1A | ||||

| Drd2 | dopamine receptor D2 | |||||

| Midbrain | ||||||

| Neuroimmune signaling | Tlr4 | toll-like receptor 4 | ||||

| Dopamine enzymes and receptors | Drd1a | dopamine receptor D1A | ||||

| Drd2 | dopamine receptor D2 | |||||

| Th | tyrosine hydroxylase | |||||

Significant effects (* p < 0.05) were observed only in the prefrontal cortex, and only in males

Three of the four neuroimmune signaling genes in the prefrontal cortex showed significant interaction effects of PCBs and LPS in males but not in females (Figure 5): Ikbkb (F(1,25) = 5.88, p < 0.05), Tlr4 (F(1,26) = 5.33, p < 0.05), and Rela (F(1,29) = 5.73, p < 0.05). More specifically, oil-exposed animals showed no response to LPS, but males exposed to PCBs showed a decrease in expression of Ikbkb (F(1,13) = 4.73, p < 0.05) and Tlr4 (F(1,13) = 7.89, p < 0.05) in response to LPS. A main effect of LPS on Rela expression was observed (F(1,29) = 7.85, p < 0.05), however this was likely driven by increased Rela expression in response to LPS in oil-exposed animals (F(1,14) = 13.80, p < 0.01), but not in PCB-exposed animals; in addition, males exposed to PCBs had greater expression of Rela, but only in those not exposed to LPS (F(1,14) = 4.79, p < 0.05). Exposure to PCBs and/or LPS did not significantly affect the relative expression of Nfkb1 in the prefrontal cortex in either sexes (Table 3; Figure 5C).

Figure 5: PCB exposure altered responses to LPS in male prefrontal cortex.

In response to PCB and LPS exposure, males showed a change in relative expression of Ikbkb (A), Rela (C), and Tlr4 (D) but not Nfkb1 (B). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM with final n per group, after removing outliers and samples that failed to amplify, shown within bars. Significant effects (*p < 0.05) are noted within sex.

In contrast to the hypothalamus, expression of dopaminergic signaling genes Drd1a, Drd2, and Th in mesocorticolimbic system was not altered by PCB exposure or the LPS challenge (Table 3).

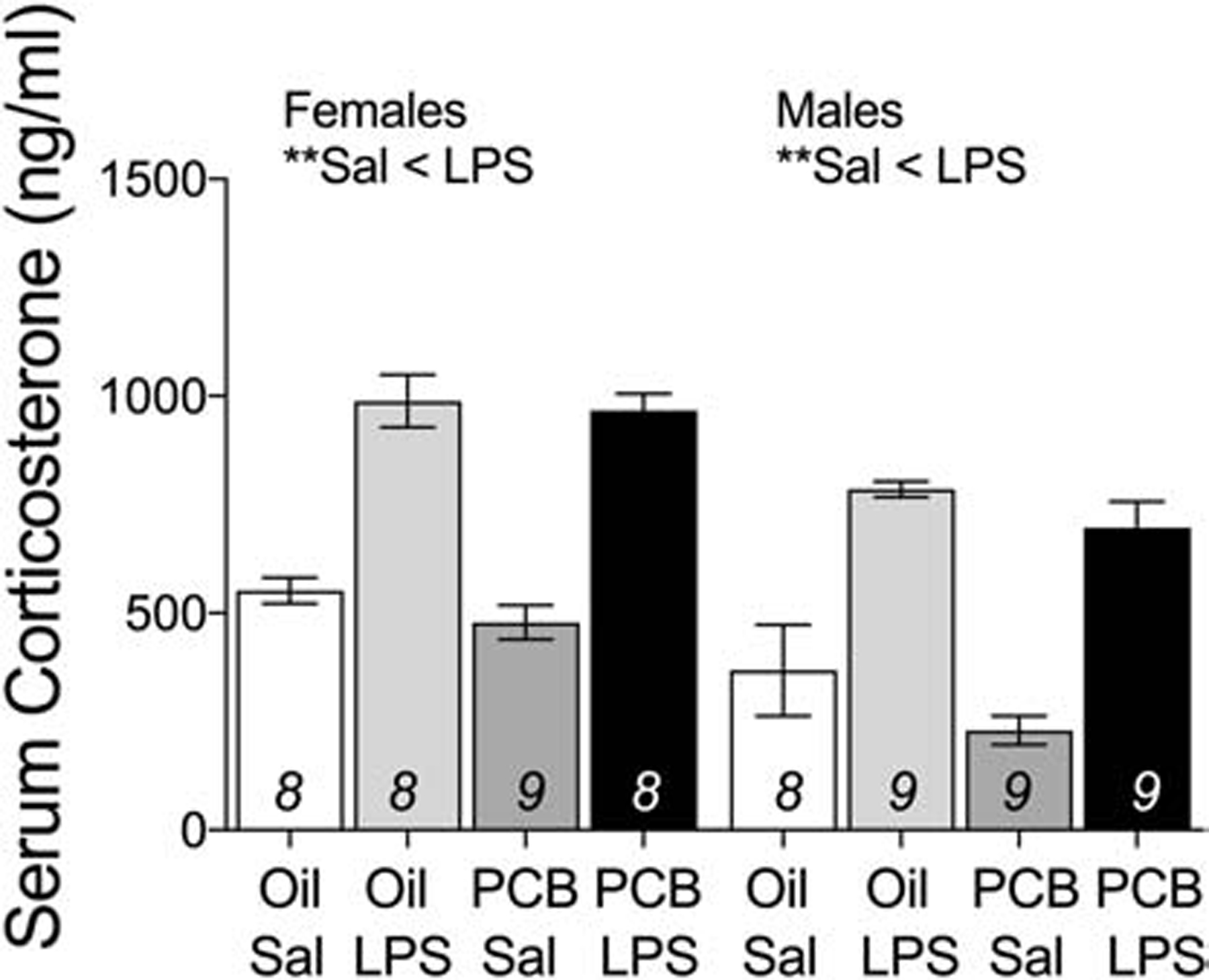

3.4. Serum corticosterone

No main effects of PCBs or interactions between PCBs and LPS on serum corticosterone concentrations were found (Figure 6). Animals exposed to LPS had higher concentrations of corticosterone than those exposed to saline, in females (F(1,33) = 113.31, p < 0.01) and in males (F(1,35) = 53.99, p < 0.01).

Figure 6: LPS increased concentrations of serum corticosterone in both males and females, independent of PCB exposure.

Data are presented as mean values ± SEM with final n per group, after outlier removal, shown within bars. Significant effects (**p < 0.01) are noted within sex.

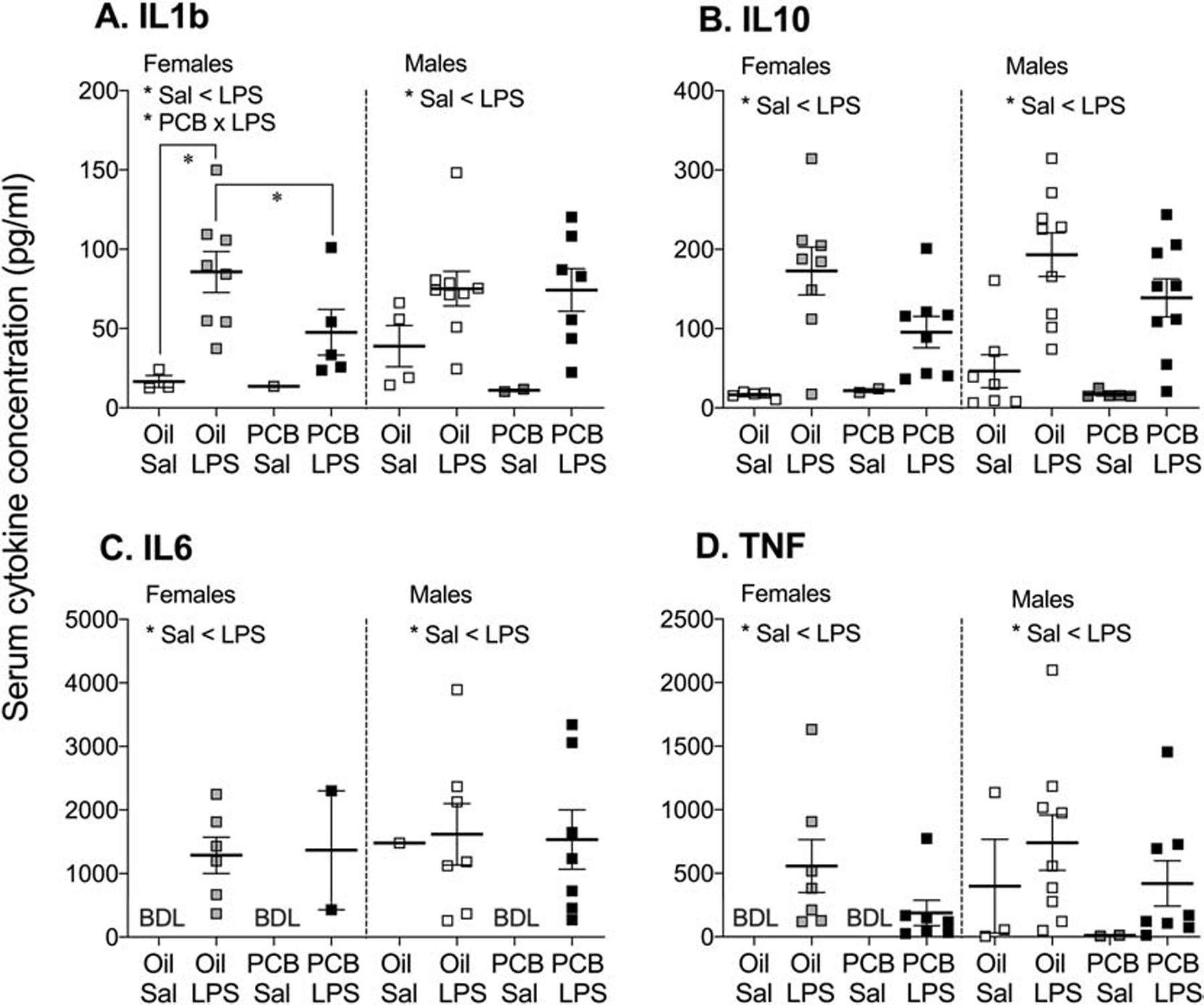

3.5. Serum cytokines

LPS challenge was associated with higher concentrations of serum IL1b (MW, p < 0.01) and IL10 (MW, p < 0.01) in both males and females (Figure 7A–B). The effect of LPS on IL10 was independent of PCB exposure, whereas the effect of LPS on IL1b concentration was present only in oil controls (MW, p < 0.01). PCB exposure was also associated with lower concentrations of IL1b in LPS challenged females (MW, p < 0.05). In both males and females, LPS challenge was associated with a greater number of samples with detectable concentrations of IL6 and TNF, independent of PCB exposure (χ2, p < 0.01, Figure 7C–D). No effects of PCB exposure or LPS challenge were found on concentrations of IL1a (data not shown).

Figure 7: LPS increased concentrations of serum cytokines, IL1b (A), IL10 (B), IL6 (C), and TNF (D), in both males and females independent of PCB exposure.

In females exposed to PCBs, the increase in IL1b is blunted. Each group included 7–9 samples, but many were below detection limits (BDL). Because of this, and the high variability within groups, data are presented as mean values ± SEM, with detectable samples shown as overlaid data points. Significant effects (*p < 0.05) are noted within sex.

4. Discussion

As a whole, our results show significant effects of perinatal PCB exposure on neuroimmune and dopaminergic measures in adolescent rats. A major finding was the extent of differences between the sexes: in the hypothalamus, extensive gene expression profiling showed that while both sexes responded to LPS, only males showed effects of PCBs, with the exception of Ikbkb. Further work done in the prefrontal cortex, midbrain, and striatum revealed region-specificity, with effects of PCBs in the mesocorticolimbic region limited to neuroimmune signaling genes in the male prefrontal cortex. LPS also affected peripheral serum cytokines in both sexes, with an effect of PCBs found only in females for IL1b; however, given the variability and the relatively low sample size, these data need to be interpreted with caution. These findings suggest that while prior PCB exposure does not cause wholesale changes to the neuroimmune system, it affects specific aspects, in a sex-specific and brain region-specific manner. These alterations could shift the developmental trajectory of the brain, potentially altering risk for mental health and substance abuse disorders that are regulated by neuroimmune signaling.

Sex-specific or sexually differentiated effects of environmental contaminants on neural outcomes are common, as described in reviews of endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) (Gore et al., 2019; Rebuli and Patisaul, 2016) and other studies in this special issue; indeed, sex differences in responses are present in a range of species, from zebrafish (Wang et al., 2015) to humans (Braun et al., 2017). However, there are several salient themes to highlight. 1) Sex-specific effects of PCBs have been detected not only in vivo, but also in the dendritic arborization and axon growth in neurons grown and treated in vitro (Keil et al., 2018; Sethi et al., 2018). 2) While the majority of basic PCB studies that include and analyze both males and females use a developmental exposure model (likely because both sexes are present in resulting litter), sex differences in neural, endocrine, and behavioral outcomes are also found in response to juvenile and adult exposures (Bell et al., 2016; Bell et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2019; Viluksela et al., 2014). 3) Sex-specific effects extend beyond the usual EDC suspects, including lead and methylmercury (Kasten-Jolly and Lawrence, 2017; Ruszkiewicz et al., 2016). As brain maturation is sex-differentiated due to differences in hormone production or sensitivity, one obvious mechanism behind these sex-specific effects is that EDCs alter hormone signaling and disrupt these developmental processes. However, it is also possible that pre-existing differences in male and female neural, endocrine, or immune systems could make them differentially responsive to non-hormonal mechanisms of toxicity. Finally, sexes may also differ in their body burdens, as is sometimes found in wildlife (Hitchcock et al., 2019; Keogh et al., 2020) and humans (Yang et al., 2018). All possibilities emphasize the need for including both sexes in analysis and considering sex as a biological variable.

4.1. Perinatal PCB exposure is associated with greater expression of neuroimmune factors in the adolescent male hypothalamus.

While PCBs are known to acutely alter activity of the NF-κB complex in a range of peripheral cells (Abliz et al., 2016; Gourronc et al., 2018; Hennig et al., 2002; Kwon et al., 2002; Phillips et al., 2018; Waugh et al., 2018), this is the first study to demonstrate that the NF-κB complex appears particularly sensitive to long-term effects of developmental PCB exposure in the brain. Specifically, in the male hypothalamus, PCB exposure increased gene expression of Nfkb1 and Rela. These genes code for the p50 and p65 subunits of the NF-κB transcription factor, respectively, that drives production of cytokines and other proinflammatory proteins, including itself (Karin, 2011). This PCB-induced increase in Nfkb1 and Rela expression is additive with an LPS-induced increase; therefore, PCBs can enhance proinflammatory signaling at both basal and immune-activated states in the hypothalamus. The only gene that was affected by PCBs in females was in this complex—Ikbkb, the protein product of which phosphorylates IκB for degradation and frees the NF-κB complex to translocate to nucleus. We previously reported this same effect of PCBs in P1 female but not male hypothalamus (Bell et al., 2018). Thus, both males and females show a generally proinflammatory response to PCBs, independent of LPS activation, but via different gene targets.

Overall, adolescent males appear to be substantially more responsive to effects of PCBs on neuroimmune signaling than females. In males, PCB exposure increased expression of Itgam, which codes for the integrin subunit CD11b and is important in reactive oxygen species production and phagocytosis in microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain (Brown and Neher, 2014; Linnartz and Neumann, 2013; Schafer et al., 2012). PCB exposure, independent of LPS challenge, also increased Tgfb2 expression in the male hypothalamus. TGFβ2 is a pleiotropic growth factor and cytokine that is generally anti-inflammatory in adulthood and regulates development (Bottner et al., 2000; Flanders et al., 1998; Sanyal et al., 2004). TGFβ1 appears to provide some auto-regulation of microglial activation (Dobolyi et al., 2012), and perhaps TGFβ2 is playing a similar role in the current study. While the NF-κB subunits studied herein are expressed in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (Dresselhaus and Meffert, 2019; Kawai and Akira, 2007), together, these findings raise microglia as a novel target of potential PCB action. Moreover, male microglia are more prevalent during neonatal development (Lenz and McCarthy, 2015; Schwarz et al., 2012), contain more active NF-κB (Guneykaya et al., 2018; Villa et al., 2019; Villa et al., 2018), and are more vulnerable to immune or toxin challenge (Hanamsagar et al., 2017; Rebuli et al., 2016; Villa et al., 2018), than female microglia. Indeed, in the current study, adolescent males showed a broader response to LPS exposure, including an increase in the expression of Tnf, a cytokine predominately, but not exclusively, produced by microglia (Bennett et al., 2016; Chung and Benveniste, 1990; Welser-Alves and Milner, 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). This Tnf effect was also present in neonatal males, but not females (Bell et al., 2018). Thus, effects of PCBs on microglia could explain why almost all of the effects of PCBs are observed only in males in this study. Differences in microglial activity between sexes could also induce sex differences in neurons and immuno-competent astrocytes (Dong and Benveniste, 2001; Kopec et al., 2018; Mallya et al., 2018; Nelson and Lenz, 2017; Siracusa et al., 2019; VanRyzin et al., 2019).

The mechanisms by which PCBs could exert these effects are numerous and not mutually exclusive. Dioxin-like PCBs can bind aryl hydrocarbon receptors to increase oxidative stress and induce NF-κB activity and cytokine production (Gourronc et al., 2018; Hennig et al., 2002), while non-dioxin-like congeners may do so by activating NAD(P)H oxidase or by directly damaging DNA (Abliz et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2003; Choi et al., 2010; Kwon et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2004; Marabini et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2018; Sipka et al., 2008). In addition, different PCB congeners can both agonize or antagonize estrogen receptor activity (Hamers et al., 2011; Pliskova et al., 2005; Warner et al., 2012), which is known to modulate both aryl hydrocarbon receptor and NF-κB activity (Frasor et al., 2015; Maggi et al., 2004). Microglia are altered depending on circulating estradiol (Lenz et al., 2013; Loram et al., 2012; Saijo et al., 2011; Sierra et al., 2008; Vegeto et al., 2006; Vegeto et al., 2001) and their activational patterns are programmed early in life (Crain et al., 2013; Villa et al., 2018), making estrogenic mechanisms an interesting possibility. Finally, some PCB congeners are known to interact with ryanodine receptors and alter thyroid hormone action (Pessah et al., 2019; Sethi et al., 2019), both of which could potentially affect neuroimmune processes (Hopp et al., 2015; Klegeris et al., 2007; Lima et al., 2001; Mancini et al., 2016). However, any effects observed in the current study are a result of both early life organizational and adolescent acute effects of a mix of PCB congeners, the metabolites of which likely shift over time; as such, continued research is required.

4.2. Perinatal PCB exposure altered responses to immune challenge in the adolescent male prefrontal cortex, but not striatum or midbrain of either sex.

Of the four regions analyzed, the prefrontal cortex was the only one affected by PCBs and LPS interactions, and again, the effects were limited to males. Specifically, interactions between PCB exposure and subsequent LPS challenge decreased or prevented expression of the NF-κB complex components Rela and Ikbkb, as well as Tlr4, a toll like receptor expressed by microglia and other cells (Aurelian et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2016). TLR4 normally binds pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to stimulate an immune reaction upstream of NF-κB activation, and Tlr4 upregulation occurs concurrent with immune and microglial activation (Doyle et al., 2017; Hoogland et al., 2015), but see (Loram et al., 2012). Thus, PCBs appear to be blunting a typical neuroimmune response in the prefrontal cortex. These results are in agreement with other studies showing that mixtures of non-dioxin-like and ortho-substituted PCBs inhibit LPS-stimulated Tlr4 expression, NF-κB activity, and cytokine production in primary mouse peritoneal macrophages (Santoro et al., 2015) and proliferation of primary mouse splenocytes (Smithwick et al., 2003).

Some remaining questions are why the effects of PCBs are so different between the hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex, and why striatum and midbrain were unaffected. One possibility could be differential sensitivity to oxidative stress, as is found in different populations of dopaminergic cells (Benskey et al., 2013; Wang and Michaelis, 2010). Another potential reason for regional differences is sensitivity to hormones, with the hypothalamus expressing significantly more receptors for estradiol and androgen than mesocorticolimbic regions (Simerly et al., 1990; Zuloaga et al., 2014). Glia in the hypothalamus are extremely responsive to estradiol perinatally (Lenz et al., 2013), but cortical glia may be differentially sensitive during adolescence. PCBs have also been shown to alter estradiol production and metabolism by disrupting activity of aromatase and estrone sulfotranferase (Hamers et al., 2011). As aromatase is known to be locally regulated within brain regions (Amateau et al., 2004; Konkle and McCarthy, 2011), and males express more aromatase than females in the hypothalamus (Wu et al., 2009), this is another possible rationale for region- and sex-specific effects of PCBs. Microglia also show different phenotypes across brain regions (Crain and Watters, 2015; De Biase et al., 2017; Pintado et al., 2011) and so may react differently to these challenges.

4.3. Perinatal PCB exposure up-regulates expression of receptors for estradiol receptor beta, dopamine, and serotonin in the hypothalamus.

In the hypothalamus, expression of Esr2, the gene that codes for ERβ, is increased by both LPS and PCB exposure in males. However this effect is most noticeable as a response to LPS in PCB-exposed animals, in agreement with effects of immune activation to increase Esr2 expression in estradiol-treated microglia and macrophages (Liu et al., 2005; Villa et al., 2015). Esr2 was affected by PCBs and LPS in neonatal siblings in a similar pattern, but in females instead of males (Bell et al., 2018). This emphasizes the dynamic nature of PCB effects across development that could be dependent on time since acute PCB exposure, metabolism of the original congeners, current developmental processes, and/or circulating gonadal hormones.

PCBs increased baseline Drd1a and Drd2 gene expression in male hypothalamus, a result consistent with the effect of Aroclor 1221 in adult male hypothalamus (Bell, 2014), independent of LPS challenge. We have previously reported that prenatal PCB exposure caused a reduction in Th, the gene that codes for the rate limiting enzyme in catecholamine production, and Slc6a3, the gene that codes for the dopamine transporter, in neonatal siblings of the animals in this study (Bell et al., 2018). As such, the greater expression of dopamine receptors in the adolescent hypothalamus may be compensating for this reduced dopamine production and content early in life. Serotonin signaling was also altered by PCB exposure, and in a similar pattern developmentally as with dopamine: Slc6a4, the gene that codes for the serotonin transporter, was decreased by PCBs in neonates while Htr2a, a gene that codes for a serotonin receptor, was increased by PCBs in adolescents. While effects of PCBs on serotonergic endpoints have been varied, the developing hypothalamus appears to be sensitive (Boix and Cauli, 2012; Dervola et al., 2015; Elnar et al., 2012; Mariussen and Fonnum, 2001). Of note is that hypothalamic dopamine and serotonin both regulate food intake (Legrand et al., 2015; Voigt and Fink, 2015). As such, these results could be contributing factors to the greater body weight found in PCB-exposed animals in the current study and is an area of future interest.

In contrast to effects in the hypothalamus, neither PCBs nor LPS altered dopaminergic gene expression throughout the mesocorticolimbic system in the current study. This regional specificity could be explained by different sensitivities of these dopaminergic populations to injury (Matzuk and Saper, 1985). While previous work has shown effects of PCBs on dopamine systems in the frontal cortex, striatum, and midbrain, these studies differ slightly in their endpoints (dopamine transporter activity or metabolism, for example) and experimental design (PCB congeners and dose, age at exposure or tissue collection, and sexes studied) which could cause these different observations (Caudle et al., 2006; Choksi et al., 1997; Dervola et al., 2015; Enayah et al., 2018; Fielding et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012; Lesmana et al., 2014; Mariussen et al., 1999; Seegal, 1994; Seegal et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2011).

4.4. Peripheral LPS altered expression of neuroimmune genes

As a strong activator of the immune system, LPS challenge altered expression of cytokine- and prostaglandin-related genes in the current study, thereby validating our experimental design. LPS also increased some of the same immune signaling genes in this study that were identified in the neonatal siblings of these animals in a companion study: Cxcl19, IL1b, Ptgs2, Ptges, and TNFa (Bell et al., 2018). The current study also identified additional genes affected in adolescent but not neonatal animals: Ccl22, Il7r, and Myd88. Interestingly, an opioid receptor response to LPS was reversed over development, as expression of Oprk1 and Oprm1 was decreased by LPS in neonates but increased by LPS in adolescents. While it is well established that neonatal immune function is immature and continues to develop during puberty (Goble et al., 2011; Holsapple et al., 2004; Van Loveren and Piersma, 2004), this opposite response to immune challenge is notable and merits further study.

The mechanism by which peripheral LPS can alter neuroimmune signaling is still an area of active study. Intraperitoneal LPS could activate neuroimmune cells via vagal nerve activity, transport of proinflammatory products like cytokines across the blood brain barrier, or signaling of epithelial cells intrinsic in the barrier itself (Hoogland et al., 2018; Nakano et al., 2015). LPS challenge did increase production of IL1b, IL6, IL10, and TNF peripherally which could have all relayed that signal to the brain. PCBs are also known to alter blood brain barrier permeability, perhaps differentially increasing relay of peripheral cytokine LPS response as a mechanism of the observed PCB x LPS interactions on Tlr4 and NF-κB complex genes in the prefrontal cortex (Choi et al., 2012). In our study, PCB exposure blunted the serum cytokine IL1b response to LPS in females; however, due to the wide spread data and low sample size, further research is needed to confirm this effect. While it is likely not a cause for the differential brain responses to PCBs or LPS, it may indicate that other immune-active peripheral tissues are being altered by PCBs, and are therefore responding to LPS differently.

4.5. Limitations

While this study raises neuroimmune processes as potential targets and effectors of PCBs’ neurotoxic effects, it also leaves several questions for future study. Ongoing work is actively investigating whether the relatively small effect sizes in gene expression translate into biologically meaningful shifts in neuroimmune system function. In addition, we used a single dose of a PCB mixture because of logistical considerations associated with eight experimental groups. We estimated this dose to be within the range of human infant exposure, but using multiple doses and confirming animal body burdens is an appropriate next step. It would also be interesting to investigate effects of non-Aroclor congeners that now constitute 10% of the maternal human serum burden, on average (Koh et al., 2015). While this Aroclor mixture does contain many of the most common congeners recently detected in maternal serum, non-legacy PCB 11 is not represented (Frame et al., 1996; Sethi et al., 2019).

4.6. Relevance to human health

Overall, this study demonstrates that exposure to an environmentally relevant dose and mixture of PCBs early in life can lead to later adolescent disruption in neuroimmune activity. Importantly, these effects are observed predominately in males and in both basal and LPS-challenged states in the hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex, respectively. Thus, this work emphasizes the importance of assessing effects of any possible immunotoxin on both male and female subjects, as to not miss sex-specific effects that may provide insights into mechanisms of action. Chronic neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, or other alterations in neuroimmune signaling are linked to neurodegenerative disorders (Ghosh et al., 2013; Hickman et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2009), mental illness (Dowlati et al., 2010; Howren et al., 2009; Hung et al., 2014), and altered reward seeking behaviors (Cheng et al., 2016; Hutchinson and Watkins, 2014; Kwon et al., 2017; Northcutt et al., 2015). In addition to genes related to neuroimmune function, genes related to both serotoninergic and dopaminergic systems were affected in the current study. Importantly, depressive-like behavior is modulated by dynamic cross-talk between microglia and serotonergic signaling (Ledo et al., 2016), while adolescent social reward is dependent on microglia and dopaminergic cell interactions (Kopec et al., 2018). The development of neuroimmune systems seems particularly important to later behavioral health (Nelson and Lenz, 2017), as NF-κB has been implicated in adolescence bipolar and major depressive disorder (Miklowitz et al., 2016), and the sex-specific development of microglia is linked to Alzheimer’s disease and Autism Spectrum Disorder (Hanamsagar et al., 2017). As such, neuroimmune dysfunction may be one mechanism behind increased depressive-like symptomology in humans exposed to PCBs (Fitzgerald et al., 2008), and an important area for continued research.

Highlights.

Maternal exposure to environmental contaminant PCBs alters offspring neuroimmune system.

PCBs altered expression of NF-κB, dopamine, and serotonin genes in adolescent rats.

In the hypothalamus, effects were independent of adolescent LPS immune challenge.

In the prefrontal cortex, PCBs altered response to adolescent LPS challenge.

Males were more affected than females, highlighting sex as an important consideration.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to thank Hilvin Molina, Mariam Saleh, Hayley Fuller, and Alyssa Guzman for their assistance with RNA extraction and quantification and Ariel Dryden for her help with PCB exposure and animal husbandry.

Funding Information: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Environmental Health and Science [R01 ES020662 and R01 ES023254 to ACG; T32 ES07247 and F32 ES023291 to MRB] and DePaul University University Research Council and Biological Sciences to MRB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abdelrahim M, Ariazi E, Kim K, Khan S, Barhoumi R, Burghardt R, Liu SX, Hill D, Finnell R, Wlodarczyk B, Jordan VC, Safe S, 2006. 3-Methylcholanthrene and other aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists directly activate estrogen receptor alpha. Cancer Res 66(4), 2459–2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abliz A, Chen C, Deng W, Wang W, Sun R, 2016. NADPH Oxidase Inhibitor Apocynin Attenuates PCB153-Induced Thyroid Injury in Rats. Int J Endocrinol 2016, 8354745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amateau SK, Alt JJ, Stamps CL, McCarthy MM, 2004. Brain estradiol content in newborn rats: sex differences, regional heterogeneity, and possible de novo synthesis by the female telencephalon. Endocrinology 145(6), 2906–2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurelian L, Warnock KT, Balan I, Puche A, June H, 2016. TLR4 signaling in VTA dopaminergic neurons regulates impulsivity through tyrosine hydroxylase modulation. Transl Psychiatry 6, e815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MR, 2014. Endocrine-disrupting actions of PCBs on brain development and social and reproductive behaviors. Curr Opin Pharmacol 19, 134–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MR, Dryden A, Will R, Gore AC, 2018. Sex differences in effects of gestational polychlorinated biphenyl exposure on hypothalamic neuroimmune and neuromodulator systems in neonatal rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 353, 55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MR, Hart BG, Gore AC, 2016. Two-hit exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls at gestational and juvenile life stages: 2. Sex-specific neuromolecular effects in the brain. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 420, 125–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MR, Thompson LM, Rodriguez K, Gore AC, 2016. Two-hit exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls at gestational and juvenile life stages: 1. Sexually dimorphic effects on social and anxiety-like behaviors. Horm Behav 78, 168–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellavance MA, Rivest S, 2012. The neuroendocrine control of the innate immune system in health and brain diseases. Immunol Rev 248(1), 36–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ML, Bennett FC, Liddelow SA, Ajami B, Zamanian JL, Fernhoff NB, Mulinyawe SB, Bohlen CJ, Adil A, Tucker A, Weissman IL, Chang EF, Li G, Grant GA, Hayden Gephart MG, Barres BA, 2016. New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(12), E1738–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benskey M, Lee KY, Parikh K, Lookingland KJ, Goudreau JL, 2013. Sustained resistance to acute MPTP toxicity by hypothalamic dopamine neurons following chronic neurotoxicant exposure is associated with sustained up-regulation of parkin protein. Neurotoxicology 37, 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron JM, Crews D, Mclachlan JA, 1994. Pcbs as Environmental Estrogens - Turtle Sex Determination as a Biomarker of Environmental Contamination. Environ Health Persp 102(9), 780–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boix J, Cauli O, 2012. Alteration of serotonin system by polychlorinated biphenyls exposure. Neurochem. Int 60(8), 809–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borja J, Taleon DM, Auresenia J, Gallardo S, 2005. Polychlorinated biphenyls and their biodegradation. Process Biochemistry 40(6), 1999–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bottner M, Krieglstein K, Unsicker K, 2000. The transforming growth factor-betas: structure, signaling, and roles in nervous system development and functions. J Neurochem 75(6), 2227–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Muckle G, Arbuckle T, Bouchard MF, Fraser WD, Ouellet E, Séguin JR, Oulhote Y, Webster GM, Lanphear BP, 2017. Associations of Prenatal Urinary Bisphenol A Concentrations with Child Behaviors and Cognitive Abilities. Environmental Health Perspectives 125(6), 067008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenhouse HC, Schwarz JM, 2016. Immunoadolescence: Neuroimmune development and adolescent behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 70, 288–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC, Neher JJ, 2014. Microglial phagocytosis of live neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 15(4), 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ, Keeling JL, Keller JN, Huang FF, Camondola S, Mattson MP, 2000. Antiinflammatory effects of estrogen on microglial activation. Endocrinology 141(10), 3646–3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT, 2009. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clinical Chemistry 55(4), 611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Drake DF, Woolwine BJ, Spivey JR, Crowe RJ, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Miller AH, 2012. Dopaminergic mechanisms of reduced basal ganglia responses to hedonic reward during interferon alfa administration. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(10), 1044–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudle WM, Richardson JR, Delea KC, Guillot TS, Wang M, Pennell KD, Miller GW, 2006. Polychlorinated biphenyl-induced reduction of dopamine transporter expression as a precursor to Parkinson’s disease-associated dopamine toxicity. Toxicol Sci 92(2), 490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Rolls ET, Qiu J, Liu W, Tang Y, Huang CC, Wang X, Zhang J, Lin W, Zheng L, Pu J, Tsai SJ, Yang AC, Lin CP, Wang F, Xie P, Feng J, 2016. Medial reward and lateral non-reward orbitofrontal cortex circuits change in opposite directions in depression. Brain 139(12), 3296–3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Choi YJ, Chen L, Zhang B, Eum SY, Abreu MT, Toborek M, 2012. Lipopolysaccharide potentiates polychlorinated biphenyl-induced disruption of the blood-brain barrier via TLR4/IRF-3 signaling. Toxicology 302(2–3), 212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W, Eum SY, Lee YW, Hennig B, Robertson LW, Toborek M, 2003. PCB 104-induced proinflammatory reactions in human vascular endothelial cells: relationship to cancer metastasis and atherogenesis. Toxicol Sci 75(1), 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YJ, Seelbach MJ, Pu H, Eum SY, Chen L, Zhang B, Hennig B, Toborek M, 2010. Polychlorinated biphenyls disrupt intestinal integrity via NADPH oxidase-induced alterations of tight junction protein expression. Environ Health Perspect 118(7), 976–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choksi NY, Kodavanti PR, Tilson HA, Booth RG, 1997. Effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on brain tyrosine hydroxylase activity and dopamine synthesis in rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol 39(1), 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung IY, Benveniste EN, 1990. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by astrocytes. Induction by lipopolysaccharide, IFN-gamma, and IL-1 beta. The Journal of Immunology 144(8), 2999–3007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain JM, Nikodemova M, Watters JJ, 2013. Microglia express distinct M1 and M2 phenotypic markers in the postnatal and adult central nervous system in male and female mice. Journal of Neuroscience Research 91(9), 1143–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain JM, Watters JJ, 2015. Microglial P2 Purinergic Receptor and Immunomodulatory Gene Transcripts Vary By Region, Sex, and Age in the Healthy Mouse CNS. Transcr Open Access 3(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, 2018. Neuroimmune Interactions: From the Brain to the Immune System and Vice Versa. Physiol. Rev 98(1), 477–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biase LM, Schuebel KE, Fusfeld ZH, Jair K, Hawes IA, Cimbro R, Zhang HY, Liu QR, Shen H, Xi ZX, Goldman D, Bonci A, 2017. Local Cues Establish and Maintain Region-Specific Phenotypes of Basal Ganglia Microglia. Neuron 95(2), 341–356 e346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKoning EP, Karmaus W, 2000. PCB exposure in utero and via breast milk. A review. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 10(3), 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervola KS, Johansen EB, Walaas SI, Fonnum F, 2015. Gender-dependent and genotype-sensitive monoaminergic changes induced by polychlorinated biphenyl 153 in the rat brain. Neurotoxicology 50, 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desaulniers D, Xiao GH, Cummings-Lorbetskie C, 2013. Effects of lactational and/or in utero exposure to environmental contaminants on the glucocorticoid stress-response and DNA methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor promoter in male rats. Toxicology 308, 20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewailly E, Ayotte P, Bruneau S, Gingras S, Belles-Isles M, Roy R, 2000. Susceptibility to infections and immune status in Inuit infants exposed to organochlorines. Environ Health Perspect 108(3), 205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewailly E, Mulvad G, Pedersen HS, Ayotte P, Demers A, Weber JP, Hansen JC, 1999. Concentration of organochlorines in human brain, liver, and adipose tissue autopsy samples from Greenland. Environ Health Perspect 107(10), 823–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobolyi A, Vincze C, Pal G, Lovas G, 2012. The neuroprotective functions of transforming growth factor beta proteins. Int J Mol Sci 13(7), 8219–8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Benveniste EN, 2001. Immune function of astrocytes. Glia 36(2), 180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctot KL, 2010. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 67(5), 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle HH, Eidson LN, Sinkiewicz DM, Murphy AZ, 2017. Sex Differences in Microglia Activity within the Periaqueductal Gray of the Rat: A Potential Mechanism Driving the Dimorphic Effects of Morphine. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 37(12), 3202–3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresselhaus EC, Meffert MK, 2019. Cellular Specificity of NF-κB Function in the Nervous System. Frontiers in immunology 10, 1043–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnar AA, Diesel B, Desor F, Feidt C, Bouayed J, Kiemer AK, Soulimani R, 2012. Neurodevelopmental and behavioral toxicity via lactational exposure to the sum of six indicator non-dioxin-like-polychlorinated biphenyls (summation operator6 NDL-PCBs) in mice. Toxicology 299(1), 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enayah SH, Vanle BC, Fuortes LJ, Doorn JA, Ludewig G, 2018. PCB95 and PCB153 change dopamine levels and turn-over in PC12 cells. Toxicology 394, 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felger JC, Alagbe O, Hu F, Mook D, Freeman AA, Sanchez MM, Kalin NH, Ratti E, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH, 2007. Effects of interferon-alpha on rhesus monkeys: a nonhuman primate model of cytokine-induced depression. Biol Psychiatry 62(11), 1324–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felger JC, Mun J, Kimmel HL, Nye JA, Drake DF, Hernandez CR, Freeman AA, Rye DB, Goodman MM, Howell LL, Miller AH, 2013. Chronic interferon-alpha decreases dopamine 2 receptor binding and striatal dopamine release in association with anhedonia-like behavior in nonhuman primates. Neuropsychopharmacology 38(11), 2179–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding JR, Rogers TD, Meyer AE, Miller MM, Nelms JL, Mittleman G, Blaha CD, Sable HJ, 2013. Stimulation-evoked dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens following cocaine administration in rats perinatally exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. Toxicol Sci 136(1), 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald EF, Belanger EE, Gomez MI, Cayo M, McCaffrey RJ, Seegal RF, Jansing RL, Hwang SA, Hicks HE, 2008. Polychlorinated biphenyl exposure and neuropsychological status among older residents of upper Hudson River communities. Environ Health Perspect 116(2), 209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Ren RF, Lippa CF, 1998. Transforming growth factor-betas in neurodegenerative disease. Prog Neurobiol 54(1), 71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame GM, Wagner RE, Carnahan JC, Brown JJF, May RJ, Smullen LA, Bedard DL, 1996. Comprehensive, quantitative, congener-specific analyses of eight aroclors and complete PCB congener assignments on DB-1 capillary GC columns. Chemosphere 33(4), 603–623. [Google Scholar]

- Frasor J, El-Shennawy L, Stender JD, Kastrati I, 2015. NF kappa B affects estrogen receptor expression and activity in breast cancer through multiple mechanisms. Mol Cell Endocrinol 418, 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Wu MD, Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, LaFerla FM, Olschowka JA, O’Banion MK, 2013. Sustained interleukin-1beta overexpression exacerbates tau pathology despite reduced amyloid burden in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. J Neurosci 33(11), 5053–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glebov K, Löchner M, Jabs R, Lau T, Merkel O, Schloss P, Steinhäuser C, Walter J, 2015. Serotonin stimulates secretion of exosomes from microglia cells. Glia 63(4), 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goble KH, Bain ZA, Padow VA, Lui P, Klein ZA, Romeo RD, 2011. Pubertal-related changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity and cytokine secretion in response to an immunological stressor. J Neuroendocrinol 23(2), 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, Toppari J, Zoeller RT, 2015. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr. Rev 36(6), E1–E150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC, Krishnan K, Reilly MP, 2019. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Effects on neuroendocrine systems and the neurobiology of social behavior. Horm Behav 111, 7–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourronc FA, Robertson LW, Klingelhutz AJ, 2018. A delayed proinflammatory response of human preadipocytes to PCB126 is dependent on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 25(17), 16481–16492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Weihe P, Needham LL, Burse VW, Patterson DG Jr., Sampson EJ, Jorgensen PJ, Vahter M, 1995. Relation of a seafood diet to mercury, selenium, arsenic, and polychlorinated biphenyl and other organochlorine concentrations in human milk. Environ Res 71(1), 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RK, Walsh E, Mosner MG, Dichter GS, 2019. A potential mechanistic role for neuroinflammation in reward processing impairments in autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychol 142, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm FA, Hu D, Kania-Korwel I, Lehmler HJ, Ludewig G, Hornbuckle KC, Duffel MW, Bergman A, Robertson LW, 2015. Metabolism and metabolites of polychlorinated biphenyls. Crit Rev Toxicol 45(3), 245–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guneykaya D, Ivanov A, Hernandez DP, Haage V, Wojtas B, Meyer N, Maricos M, Jordan P, Buonfiglioli A, Gielniewski B, Ochocka N, Comert C, Friedrich C, Artiles LS, Kaminska B, Mertins P, Beule D, Kettenmann H, Wolf SA, 2018. Transcriptional and Translational Differences of Microglia from Male and Female Brains. Cell Rep 24(10), 2773–2783 e2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers T, Kamstra JH, Cenijn PH, Pencikova K, Palkova L, Simeckova P, Vondracek J, Andersson PL, Stenberg M, Machala M, 2011. In Vitro Toxicity Profiling of Ultrapure Non-Dioxin-like Polychlorinated Biphenyl Congeners and Their Relative Toxic Contribution to PCB Mixtures in Humans. Toxicol. Sci 121(1), 88–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers T, Kamstra JH, Cenijn PH, Pencikova K, Palkova L, Simeckova P, Vondracek J, Andersson PL, Stenberg M, Machala M, 2011. In vitro toxicity profiling of ultrapure non-dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyl congeners and their relative toxic contribution to PCB mixtures in humans. Toxicol Sci 121(1), 88–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanamsagar R, Alter MD, Block CS, Sullivan H, Bolton JL, Bilbo SD, 2017. Generation of a microglial developmental index in mice and in humans reveals a sex difference in maturation and immune reactivity. Glia 65(9), 1504–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hany J, Lilienthal H, Sarasin A, Roth-Härer A, Fastabend A, Dunemann L, Lichtensteiger W, Winneke G, 1999. Developmental exposure of rats to a reconstituted PCB mixture or Aroclor 1254: effects on organ weights, aromatase activity, sex hormone levels, and sweet preference behavior. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 158(3), 231–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayley S, Mangano E, Crowe G, Li N, Bowers WJ, 2011. An in vivo animal study assessing long-term changes in hypothalamic cytokines following perinatal exposure to a chemical mixture based on Arctic maternal body burden. Environ Health 10, 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann C, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Nielsen F, Heinzow B, Weihe P, Grandjean P, 2010. Serum concentrations of antibodies against vaccine toxoids in children exposed perinatally to immunotoxicants. Environ Health Perspect 118(10), 1434–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann C, Grandjean P, Weihe P, Nielsen F, Budtz-Jorgensen E, 2006. Reduced antibody responses to vaccinations in children exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. PLoS Med 3(8), e311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig B, Hammock BD, Slim R, Toborek M, Saraswathi V, Robertson LW, 2002. PCB-induced oxidative stress in endothelial cells: modulation by nutrients. Int J Hyg Environ Health 205(1–2), 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman S, Izzy S, Sen P, Morsett L, El Khoury J, 2018. Microglia in neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci 21(10), 1359–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock DJ, Andersen T, Varpe Ø, Borgå K, 2019. Effects of Maternal Reproductive Investment on Sex-Specific Pollutant Accumulation in Seabirds: A Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol 53(13), 7821–7829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hites RA, Foran JA, Carpenter DO, Hamilton MC, Knuth BA, Schwager SJ, 2004. Global assessment of organic contaminants in farmed salmon. Science 303(5655), 226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstenbach K, van Leeuwen DM, Gmuender H, Gottschalk RW, Stolevik SB, Nygaard UC, Lovik M, Granum B, Namork E, Meltzer HM, Kleinjans JC, van Delft JH, van Loveren H, 2012. Toxicogenomic profiles in relation to maternal immunotoxic exposure and immune functionality in newborns. Toxicol Sci 129(2), 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsapple MP, Paustenbach DJ, Charnley G, West LJ, Luster MI, Dietert RR, Burns-Naas LA, 2004. Symposium summary: children’s health risk—what’s so special about the developing immune system? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 199(1), 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogland IC, Houbolt C, van Westerloo DJ, van Gool WA, van de Beek D, 2015. Systemic inflammation and microglial activation: systematic review of animal experiments. J Neuroinflammation 12, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogland ICM, Westhoff D, Engelen-Lee JY, Melief J, Valls Seron M, Houben-Weerts J, Huitinga I, van Westerloo DJ, van der Poll T, van Gool WA, van de Beek D, 2018. Microglial Activation After Systemic Stimulation With Lipopolysaccharide and Escherichia coli. Front Cell Neurosci 12, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoops D, Flores C, 2017. Making Dopamine Connections in Adolescence. Trends Neurosci. 40(12), 709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp SC, Royer SE, D’Angelo HM, Kaercher RM, Fisher DA, Wenk GL, 2015. Differential neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of L-type voltage dependent calcium channel and ryanodine receptor antagonists in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 10(1), 35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]