Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: acute pain, analgesics, nonnarcotic, analgesics, opioid, critical illness, meta-analysis, pain management

Objectives:

This systematic review and meta-analysis addresses the efficacy and safety of nonopioid adjunctive analgesics for patients in the ICU.

Data Sources:

We searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, CINAHL Plus, and Web of Science.

Study Selection:

Two independent reviewers screened citations. Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials comparing efficacy and safety of an adjuvant-plus-opioid regimen to opioids alone in adult ICU patients.

Data Extraction:

We conducted duplicate screening of citations and data abstraction.

Data Synthesis:

Of 10,949 initial citations, we identified 34 eligible trials. These trials examined acetaminophen, carbamazepine, clonidine, dexmedetomidine, gabapentin, ketamine, magnesium sulfate, nefopam, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (including diclofenac, indomethacin, and ketoprofen), pregabalin, and tramadol as adjunctive analgesics. Use of any adjuvant in addition to an opioid as compared to an opioid alone led to reductions in patient-reported pain scores at 24 hours (standard mean difference, –0.88; 95% CI, –1.29 to –0.47; low certainty) and decreased opioid consumption (in oral morphine equivalents over 24 hr; mean difference, 25.89 mg less; 95% CI, 19.97–31.81 mg less; low certainty). In terms of individual medications, reductions in opioid use were demonstrated with acetaminophen (mean difference, 36.17 mg less; 95% CI, 7.86–64.47 mg less; low certainty), carbamazepine (mean difference, 54.69 mg less; 95% CI, 40.39–to 68.99 mg less; moderate certainty), dexmedetomidine (mean difference, 10.21 mg less; 95% CI, 1.06–19.37 mg less; low certainty), ketamine (mean difference, 36.81 mg less; 95% CI, 27.32–46.30 mg less; low certainty), nefopam (mean difference, 70.89 mg less; 95% CI, 64.46–77.32 mg less; low certainty), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (mean difference, 11.07 mg less; 95% CI, 2.7–19.44 mg less; low certainty), and tramadol (mean difference, 22.14 mg less; 95% CI, 6.67–37.61 mg less; moderate certainty).

Conclusions:

Clinicians should consider using adjunct agents to limit opioid exposure and improve pain scores in critically ill patients.

Opioids are commonly used in critically ill patients with the intent to treat pain and facilitate administration of critical care. Observational research has shown opioids are used in over 80% of mechanically ventilated ICU patients (1). However, opioid use has been associated with serious side effects such as respiratory depression (2), gastrointestinal dysfunction (3), and immunosuppression (4). Older adults, a growing proportion of ICU admissions, may be even more susceptible to side effects of opioids due to altered pharmacokinetics, polypharmacy, and decreased physiologic reserve (5).

At the same time, acute pain causes distress for patients, caregivers, and families (6). Furthermore, inadequate treatment of acute pain is a well-known risk factor for the development of chronic pain, which may occur in up to 33% of ICU survivors (7, 8). Both the use of opioids and memories of severe acute pain have been linked to development of post-traumatic stress disorder after ICU discharge (6).

Use of adjuvant medications, in addition to opioids, may help provide effective analgesia while minimizing unwanted side effects. There is evidence for the use of nonopioid analgesics in other acute care settings such as emergency departments (9) and postanesthetic care units (10), but the efficacy and degree of use of nonopioid analgesics in ICU are not well documented.

The 2018 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption (PADIS guidelines)recommended the use of a limited number of adjuvants in addition to opioids. Initial searches and data summaries were performed in support of the PADIS guideline, which summarized published evidence up to 2015 (11). However, subsequent to the publication of these guidelines, the scope of this review was expanded, and searches updated in order to include the latest data. Here we present results of a systematic review and meta-analysis summarizing the current evidence for opioid-sparing adjuvant analgesics in adult ICU patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (identification number: CRD42017057044) on February 1, 2017.

Data Sources and Searches

In collaboration with an experienced medical librarian (12), we developed the search strategy using keywords for the concepts of intensive care, cardiac or abdominal surgery, medications, and pain. The search was not limited by language or date. The PubMed search strategy can be found in Supplemental Data 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223). We searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Collaboration, CINAHL, and Web of Science from inception to October 1, 2019. We also reviewed conference abstracts from the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and SCCM for the last 2 years.

Study Selection

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the efficacy of an adjuvant-plus-opioid regimen to opioids alone in adult (over 18 yr old) ICU patients. Opioid regimens could include both scheduled and PRN (as needed) doses or PRN only. Studies comparing multiple adjuvant regimens to one another without a placebo/control group were excluded. For the purposes of this study, tramadol was considered a nonopioid adjuvant medication. Trials evaluating interventions that started outside of the ICU (e.g., in the operating room), were solely peri-procedural (e.g., for burn dressing changes or line insertions), or were regional in nature (e.g., peripheral nerve blocks or epidural catheters) were excluded.

Screening of search results, data collection, and risk of bias assessments were conducted in duplicate by two independent reviewers. Reviewers performed screening in two stages, initially assessing titles and abstracts, and then full articles. We recorded reasons for exclusion at the full article review stage. We included the following outcomes: pain scores (at 24 hr, or the closest reported time point), opioid consumption during the intervention period, duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay, and adverse events.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

We performed data extraction independently and in duplicate using predefined data abstraction forms. A third reviewer resolved disagreements. Abstracted data included characteristics of study participants (i.e., age, gender, acuity, surgical [vs medical]); the treatment regimen for both opioid alone and adjuvant analgesic arms; the type and timing of formal pain assessments; duration of follow-up; target sedation levels; number of patients included and randomized; and the outcome data. When necessary, we contacted authors of eligible studies to request supplemental data. We converted reported data on opioid consumption into 24-hour oral morphine equivalents (OME) using standardized methods (13).

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for risk of bias assessment (14). We assessed the overall certainty of evidence for each intervention using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (15).

Data Analysis

We performed all analyses using RevMan software, Version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) (16) and using the random-effects model. We present results using mean difference (MD) or standard mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI. For studies that did not report sd, we converted interquartile ranges to sd using methods suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration (17). When outcomes were reported only graphically, we used an online plot digitizer to obtain numeric estimates for analysis (18).

RESULTS

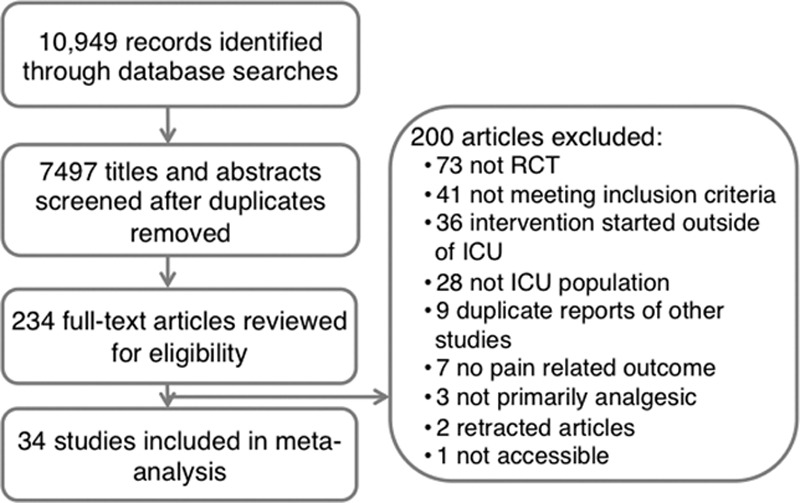

The flow diagram for the systematic review is outlined in Figure 1. Of 10,949 citations initially identified in the search, 7,497 remained after removal of duplicates, 7,263 were excluded at title and abstract screening, and 200 at full-text review leaving 34 trials that met eligibility criteria. Of these, 11 studied dexmedetomidine (19–29), seven studied acetaminophen (30–36), six studied nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (including diclofenac, indomethacin, and ketoprofen) (30, 31, 33, 37–39), four studied ketamine (40–43), three studied nefopam (37, 44, 45), two studied tramadol (30, 46), two studied gabapentin (47, 48), two studied carbamazepine (48, 49), one studied clonidine (50), one studied magnesium sulfate (51), and one studied pregabalin (52). Several studies had multiple intervention arms studying more than one adjuvant analgesic in comparison to an opioid alone. Most studies (25/34, 74%) focused on surgical ICU patients, and two focused on only Guillain-Barré syndrome patients; the remainder evaluated a mixed medical-surgical population. Full characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. Supplemental Table 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223) presents the risk of bias for each study. Eighteen studies were judged to be at low risk of bias and four at high risk of bias; the overall risk of bias was unclear for the remaining 12.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

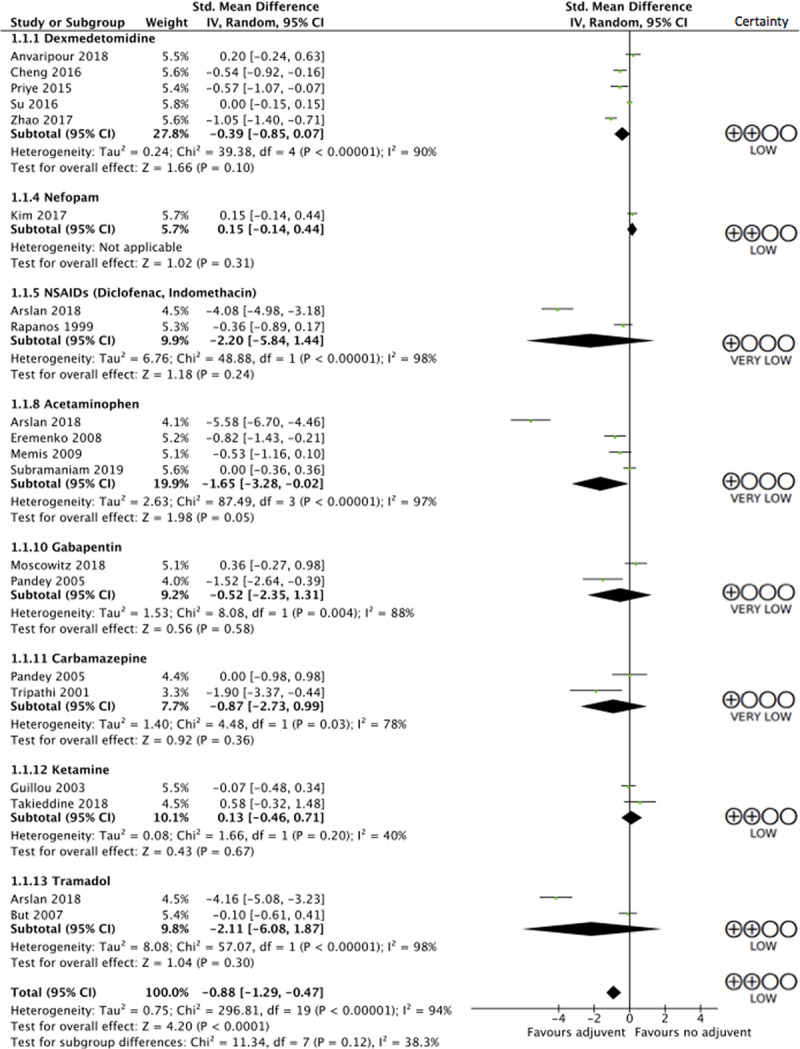

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Pain Scores

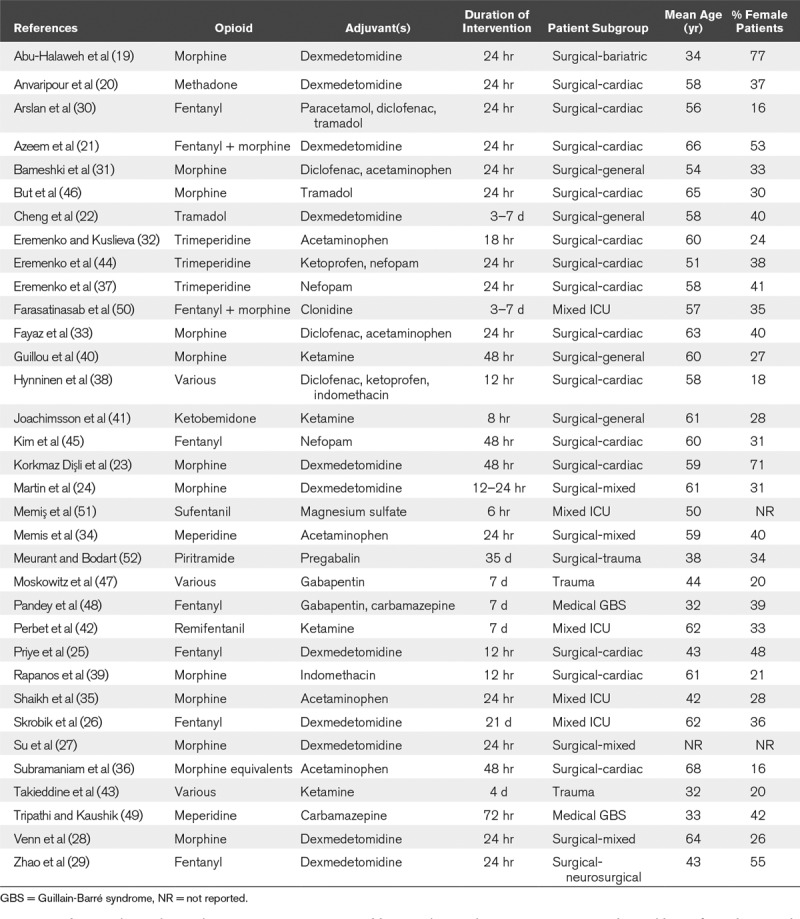

Use of any adjuvant, in addition to an opioid, led to reductions in patient-reported pain scores at 24 hours (SMD, 0.88 lower; 95% CI, 1.29–0.47 lower; low certainty; see Figure 2 for forest plot and Supplemental Table 2 [Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223] for GRADE assessments). Examining individual medications, only adjunctive acetaminophen (SMD, 1.65 lower; 95% CI, 3.28–0.02 lower) demonstrated lower pain scores at 24 hours as compared with opioids alone. However, this estimate is based on very low certainty evidence and limited by imprecision.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of pain scores at 24 hr after intervention. df = degrees of freedom, NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

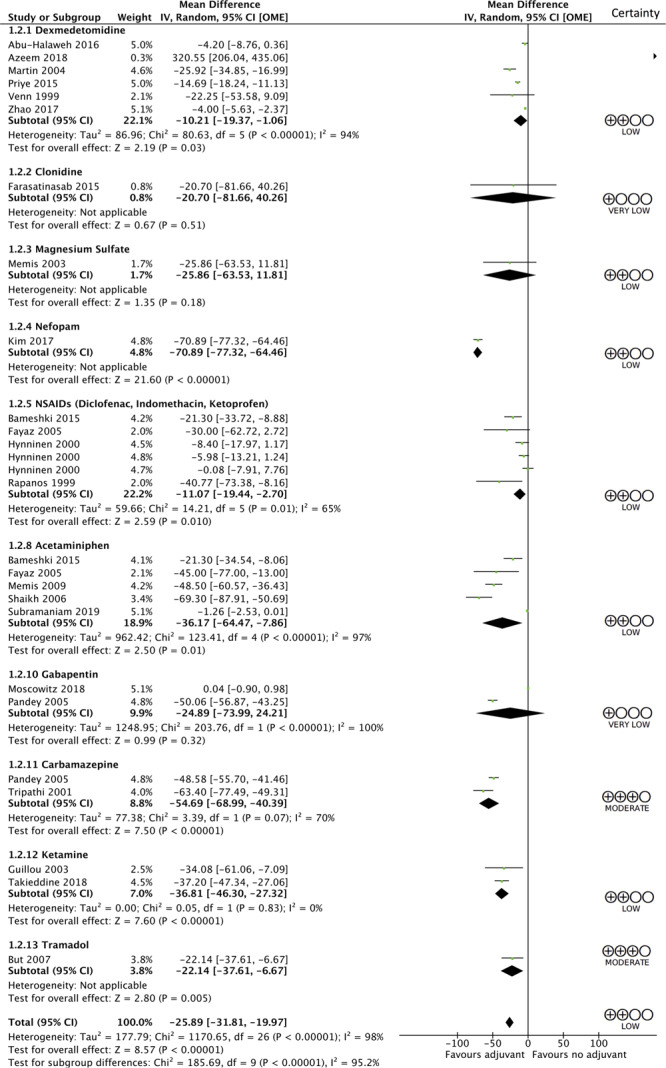

Opioid Consumption

Decreased opioid consumption (in OME over 24 hr) was demonstrated with the use of any adjuvant analgesic (MD, 25.89 mg less; 95% CI, 19.97–31.81 mg less; low certainty; see Figure 3 for forest plot and Supplemental Table 2 [Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223] for GRADE assessments). Among individual medications, reductions in opioid use (24 hr morphine equivalent) were demonstrated with dexmedetomidine (MD, 10.21 mg less; 95% CI, 1.06–19.37 mg less; low certainty), nefopam (MD, 70.89 mg less; 95% CI, 64.46–77.32 mg less; low certainty), NSAIDs (MD, 11.07 mg less; 95% CI, 2.7–19.44 mg less; low certainty), acetaminophen (MD, 36.17 mg less; 95% CI, 7.86–64.47 mg less; low certainty), carbamazepine (MD, 54.69 less; 95% CI, 40.39–68.99 mg less; moderate certainty), ketamine (MD, 36.81 mg less; 95% CI, 27.32–46.30 mg less; low certainty), and tramadol (MD, 22.14 mg less; 95% CI, 6.67–37.61 mg less; moderate certainty).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of opioid consumption in first 24 hr of intervention. df = degrees of freedom, OME = oral morphine equivalents.

Duration of Mechanical Ventilation and ICU Stay

Reductions in duration of mechanical ventilation (1.13 hr less; 95% CI, 0.39–1.86 hr less) and ICU length of stay (0.19 d less; 95% CI, 0.11–0.27 d less) were shown with use of any adjuvant analgesic, although this was based on very low certainty evidence and the magnitude of difference was of minimal clinical importance. No individual adjuvant medication demonstrated an effect on either duration of mechanical ventilation or ICU length of stay. See Supplemental Table 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223) for both the data and GRADE assessments.

Adverse Events

Very few adverse events were reported across the included studies. Given this, and the heterogeneity in how these were reported, we were unable to summarize this outcome quantitatively. Supplemental Table 3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223) provides a narrative summary of adverse events.

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analysis demonstrated consistent reductions in pain scores and opioid consumption in medical ICU patients, surgical ICU patients, and cardiac surgical ICU patients (Supplemental Figs. 1–4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223). There were no credible subgroup effects seen.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis is the most comprehensive and current summary of adjuvant analgesic medications in ICU patients. We have expanded on the 2018 PADIS guideline to provide results of a broader, more recent search, and report on a larger number of agents (11).

Our search results support PADIS conditional recommendations for the use of acetaminophen, ketamine, nefopam, and carbamazepine in reducing daily opioid consumption. Although our analysis also found similar efficacy with NSAIDs, the PADIS guidelines suggested against routine use of NSAIDs (despite their potential opioid-sparing effects) due to unpublished anticipated concerns regarding side effects such as bleeding and renal dysfunction (11).

In order to pool data from studies that included different opioids in their analgesic regimens, we have converted the opioid consumption reported in individual articles to OME. This was done using standardized conversion methods, with input from content experts including critical care pharmacists. However, the differences in opioid types and regimens used in individual studies limit the ability to directly compare absolute opioid consumption between studies

Our results are consistent with a recent meta-analysis that also aimed to summarize the use of nonopioid analgesics for ICU patients (53). In comparison to this review, our search was broader and included more citations, more eligible studies, and more potential adjunctive medications leading to more precise and clinically useful results.

The data analysis demonstrated a signal for potential analgesic benefit through lower pain scores from the use of IV acetaminophen or dexmedetomidine. However, we were unable to summarize side effects such as hypotension, which has been associated with these agents (54–57). Tramadol also showed a signal for a potential opioid-sparing effect in analysis, although widespread use in ICU patients is limited by its formulation only as tablet that cannot be crushed and administered enterally, and by side effects, which are of concern particularly in patients with renal dysfunction (58).

This analysis also showed a reduction in opioid consumption and improved pain scores with use of dexmedetomidine. There is increasing interest in the use of dexmedetomidine as a sedative in intensive care (56). Although recent evidence shows no benefit over standard sedation in the general ICU population (59), there may be utility in patients with pathologies such as alcohol or drug withdrawal (55). Some studies suggest a direct analgesic effect of dexmedetomidine (60), although there is also a suggestion that its opioid-sparing properties may be due to altered perception of pain and anxiolysis, rather than direct analgesia (61). Regardless of its mechanism, dexmedetomidine may be a useful adjunct and sedative medication for patients in whom opioid-sparing is a priority.

Studies of regional anesthesia techniques or of interventions started outside of the ICU (e.g., those started in the operating room or emergency department) were intentionally excluded from this review. We made this decision a priori in order to limit clinical heterogeneity and focus on interventions that are independent of specific regional anesthesia skill sets and equipment and to provide guidance specific to ICU clinicians.

Most of the trials included only subgroups of surgical patients (e.g., cardiac surgery or trauma) or those with Guillain-Barré syndrome. This may limit generalizability of our results to medical patients and highlights the need for more research in this area. However, subgroup analysis demonstrated that these findings of improved pain scores and reduced opioid consumption were consistent across medical patients, surgical patients, and cardiac surgical patients.

ICU patients have a wide range of pain pathologies, and therefore pain quality and optimal treatment may vary dramatically from one patient to the next. For example, a patient with localized nociceptive pain from trauma or surgery may respond differently than one with neuropathic pain or another with diffuse musculoskeletal pain from immobility. As with many other aspects of ICU care, it is unlikely that any one intervention would be appropriate for all patients; rather, clinicians should judge the advantages and side effect profiles of each medication on a patient-by-patient basis. Although there was insufficient data to examine subgroups such as those with Guillain-Barré syndrome or trauma admissions, Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included studies specifically highlighting the patient population which was studied. This may assist clinicians in determining the applicability of these findings to their patients. Overall, this review suggests that using some adjunctive agents, perhaps targeted to the patient type and quality of pain, is better than using opioids alone.

Unfortunately, we were unable to pool results for adverse events as the included studies variably and heterogeneously reported these outcomes. As outlined in Supplemental Table 3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A223), the majority of reported adverse outcomes were short-term such as bleeding or changes in blood pressure. Although these are important, other long-term adverse effects such as delirium and ileus, which are more challenging to measure and capture, were rarely reported in the included studies. This reflects a systemic under-reporting of harm outcomes for both opioids and adjuvant analgesic medications. Given the risks of adverse effects on many organ systems with both opioids and analgesic medications, there is a need for more careful data collection in this area.

The conclusions from this study are limited by low certainty of evidence, heterogeneity of studies (with respect to both populations and intervention regimes), and a lack of comprehensive reporting of adverse events. Strengths include a comprehensive search with explicit eligibility criteria, a priori registration of the study protocol, analysis and data collection by independent paired reviewers, input from content experts and formal evaluation of evidence certainty using GRADE methodology.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians should consider using adjunct agents to limit opioid exposure and improve pain scores in critically ill patients. Future RCTs are needed to better understand comparative effectiveness of different adjuncts, identify which subgroups of patients are most likely to benefit, and more adequately capture the harm that may be associated with use of these medications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thomas Kim assisted with screening of Korean language articles.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

Dr. Rochwerg is supported by a Hamilton Health Sciences Early Career Research Award. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burry LD, Williamson DR, Perreault MM, et al. Analgesic, sedative, antipsychotic, and neuromuscular blocker use in Canadian intensive care units: A prospective, multicentre, observational study. Can J Anaesth. 2014; 61:619–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pattinson KT. Opioids and the control of respiration. Br J Anaesth. 2008; 100:747–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chappell D, Rehm M, Conzen P. Opioid-induced constipation in intensive care patients: Relief in sight? Crit Care. 2008; 12:161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei G, Moss J, Yuan CS. Opioid-induced immunosuppression: Is it centrally mediated or peripherally mediated? Biochem Pharmacol. 2003; 65:1761–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luchting B, Azad SC. Pain therapy for the elderly patient: Is opioid-free an option? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019; 32:86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Patel MB. Intensive care unit delirium and intensive care unit-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Surg Clin North Am. 2017; 97:1215–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stamenkovic DM, Laycock H, Karanikolas M, et al. Chronic pain and chronic opioid use after intensive care discharge - is it time to change practice? Front Pharmacol. 2019; 10:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puntillo KA, Naidu R. Chronic pain disorders after critical illness and ICU-acquired opioid dependence: Two clinical conundra. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016; 22:506–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdolrazaghnejad A, Banaie M, Tavakoli N, et al. Pain management in the emergency department: A review article on options and methods. Adv J Emerg Med. 2018; 2:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL. Postoperative multimodal analgesia pain management with nonopioid analgesics and techniques: A review. JAMA Surg. 2017; 152:691–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46:e825–e873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weightman AL, Williamson J; Library & Knowledge Development Network (LKDN) Quality and Statistics Group. The value and impact of information provided through library services for patient care: A systematic review. Health Info Libr J. 2005; 22:4–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen S, Degenhardt L, Hoban B, et al. A synthesis of oral morphine equivalents (OME) for opioid utilisation studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016; 25:733–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011; 343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011; 64:383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager (RevMan). 2014, Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Green SE. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011. Copenhagen, The Cochrane Collaboration [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huwaldt J. Source Forge: Plot Digitizer. 2013 Available at: http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net. Accessed October 16, 2018.

- 19.Abu-Halaweh S, Obeidat F, Absalom AR, et al. Dexmedetomidine versus morphine infusion following laparoscopic bariatric surgery: Effect on supplemental narcotic requirement during the first 24 h. Surg Endosc. 2016; 30:3368–3374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anvaripour A, Ashkpour H, Marashian M, et al. The efficacy and side effects of dexmedetomidine and morphine in patient-controlled analgesia method after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Int J Pharm Res. 2018; 10:251–256 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azeem TMA, Yosif NE, Alansary AM, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs morphine and midazolam in the prevention and treatment of delirium after adult cardiac surgery; a randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2018; 12:190–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng M, Shi J, Gao T, et al. The addition of dexmedetomidine to analgesia for patients after abdominal operations: A prospective randomized clinical trial. World J Surg. 2017; 41:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korkmaz Dişli Z, Çelebi N, Canbay Ö, et al. Comparison of morphine and dexmedetomidine delivered by patient-controlled analgesia device during the postoperative period of coronary artery bypass surgery. Anestezi Dergisi. 2013; 21:29–36 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin E, Ramsay G, Mantz J, et al. The role of the alpha2-adrenoceptor agonist dexmedetomidine in postsurgical sedation in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2003; 18:29–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Priye S, Jagannath S, Singh D, et al. Dexmedetomidine as an adjunct in postoperative analgesia following cardiac surgery: A randomized, double-blind study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2015; 9:353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skrobik Y, Duprey MS, Hill NS, et al. Low-dose nocturnal dexmedetomidine prevents ICU delirium. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 197:1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su X, Meng ZT, Wu XH, et al. Dexmedetomidine for prevention of delirium in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016; 388:1893–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venn RM, Bradshaw CJ, Spencer R, et al. Preliminary UK experience of dexmedetomidine, a novel agent for postoperative sedation in the intensive care unit. Anaesthesia. 1999; 54:1136–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao LH, Shi ZH, Chen GQ, et al. Use of dexmedetomidine for prophylactic analgesia and sedation in patients with delayed extubation after craniotomy: A randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2017; 29:132–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arslan Y, Kudsioglu T, Yapici N, et al. Administration of paracetamol, diclofenac sodium, and tramadol for postoperative analgesia after coronary artery bypass surgery. GKDA Derg. 2018; 24:23–28 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bameshki A, Peivandi Yazdi A, Sheybani S, et al. The assessment of addition of either intravenous paracetamol or diclofenac suppositories to patient-controlled morphine analgesia for postgastrectomy pain control. Anesth Pain Med. 2015; 5:e29688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eremenko AA, Kuslieva EV. Analgesic and opioid-sparing effects of intravenous paracetamol in the early period after aortocoronary bypass surgery. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 200811–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fayaz MK, Abel RJ, Pugh SC, et al. Opioid-sparing effects of diclofenac and paracetamol lead to improved outcomes after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004; 18:742–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Memis D, Inal MT, Kavalci G, et al. Intravenous paracetamol reduced the use of opioids and extubation time after major surgery in intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2009; 35:S136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaikh N, Kettern MA, Ali Ahmed AH, et al. Morphine sparing effect of proparacetamol in surgical and trauma intensive care. Middle East J Emergency Med. 2006; 6:28–30 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subramaniam B, Shankar P, Mueller A. Intravenous acetaminophen for postoperative delirium-reply. JAMA. 2019; 322:272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eremenko A, Sorokina L, Pavlov M. Ketoprophen and nefopam combination for postoperative analgesia with minimal use of narcotic analgesics in cardio-surgical patients. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 201311–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hynninen MS, Cheng DC, Hossain I, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in treatment of postoperative pain after cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2000; 47:1182–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rapanos T, Murphy P, Szalai JP, et al. Rectal indomethacin reduces postoperative pain and morphine use after cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1999; 46:725–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guillou N, Tanguy M, Seguin P, et al. The effects of small-dose ketamine on morphine consumption in surgical intensive care unit patients after major abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg. 2003; 97:843–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joachimsson PO, Hedstrand U, Eklund A. Low-dose ketamine infusion for analgesia during postoperative ventilator treatment. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1986; 30:697–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perbet S, Verdonk F, Godet T, et al. Low doses of ketamine reduce delirium but not opiate consumption in mechanically ventilated and sedated ICU patients: A randomised double-blind control trial. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018; 37:589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takieddine SC, Droege CA, Ernst N, et al. Ketamine versus hydromorphone patient-controlled analgesia for acute pain in trauma patients. J Surg Res. 2018; 225:6–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eremenko AA, Sorokina LS, Pavlov MV. The use of central acting analgesic nefopam in postoperative analgesia in cardiac surgery patients. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 201378–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim K, Kim WJ, Choi DK, et al. The analgesic efficacy and safety of nefopam in patient-controlled analgesia after cardiac surgery: A randomized, double-blind, prospective study. J Int Med Res. 2014; 42:684–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.But AK, Erdil F, Yucel A, et al. The effects of single-dose tramadol on post-operative pain and morphine requirements after coronary artery bypass surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007; 51:601–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moskowitz EE, Garabedian L, Hardin K, et al. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial of gabapentin vs. placebo for acute pain management in critically ill patients with rib fractures. Injury. 2018; 49:1693–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandey CK, Raza M, Tripathi M, et al. The comparative evaluation of gabapentin and carbamazepine for pain management in Guillain-Barré syndrome patients in the intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2005; 101:220–225, table of contents [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tripathi M, Kaushik S. Carbamezapine for pain management in Guillain-Barré syndrome patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2000; 28:655–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farasatinasab M, Kouchek M, Sistanizad M, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of clonidine impact on sedation of mechanically ventilated ICU patients. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015; 14:167–175 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Memiş D, Turan A, Karamanlioglu B, et al. Comparison of sufentanil with sufentanil plus magnesium sulphate for sedation in the intensive care unit using bispectral index. Crit Care. 2003; 7:R123–R128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meurant F, Bodart A. Sparing analgesic effect using pregabaline in postsurgical trauma patients in the ICU. Crit Care. 2006; 10:P439 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao H, Yang S, Wang H, et al. Non-opioid analgesics as adjuvants to opioid for pain management in adult patients in the ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2019; 54:136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cantais A, Schnell D, Vincent F, et al. Acetaminophen-induced changes in systemic blood pressure in critically ill patients: Results of a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44:2192–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.VanderWeide LA, Foster CJ, MacLaren R, et al. Evaluation of early dexmedetomidine addition to the standard of care for severe alcohol withdrawal in the ICU: A retrospective controlled cohort study. J Intensive Care Med. 2016; 31:198–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keating GM. Dexmedetomidine: A review of its use for sedation in the intensive care setting. Drugs. 2015; 75:1119–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chanques G, Sebbane M, Constantin JM, et al. Analgesic efficacy and haemodynamic effects of nefopam in critically ill patients. Br J Anaesth. 2011; 106:336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vazzana M, Andreani T, Fangueiro J, et al. Tramadol hydrochloride: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse side effects, co-administration of drugs and new drug delivery systems. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015; 70:234–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shehabi Y, Howe BD, Bellomo R, et al. ; ANZICS Clinical Trials Group and the SPICE III Investigators. Early sedation with dexmedetomidine in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:2506–2517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hall JE, Uhrich TD, Barney JA, et al. Sedative, amnestic, and analgesic properties of small-dose dexmedetomidine infusions. Anesth Analg. 2000; 90:699–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weerink MAS, Struys MMRF, Hannivoort LN, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dexmedetomidine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017; 56:893–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.