Abstract

Emergency department (ED) crowding represents an international crisis that may affect the quality and access of health care. We conducted a comprehensive PubMed® search to identify articles that 1) studied causes, effects, or solutions of ED crowding; 2) described data collection and analysis methodology; 3) occurred in a general ED setting; and 4) focused on everyday crowding. Two independent reviewers identified the relevant articles by consensus. We applied a five-level quality assessment tool to grade the methodology of each study. From 4,271 abstracts and 188 full-text articles, the reviewers identified 93 articles meeting the inclusion criteria. A total of 33 articles studied causes, 27 articles studied effects, and 40 articles studied solutions of ED crowding. Commonly studied causes of crowding included non-urgent visits, frequent-flyer patients, influenza season, inadequate staffing, inpatient boarding, and hospital bed shortages. Commonly studied effects of crowding included patient mortality, transport delays, treatment delays, ambulance diversion, patient elopement, and financial impact. Commonly studied solutions of crowding included additional personnel, observation units, hospital bed access, non-urgent referrals, ambulance diversion, destination control, crowding measures, and queuing theory. The results illustrated the complex, multi-faceted characteristics of the ED crowding problem. Additional high-quality studies may provide valuable contributions towards better understanding and alleviating the daily crisis. This structured overview of the literature may help to identify future directions for the crowding research agenda.

Introduction

The international crisis of emergency department (ED) crowding has received considerable attention, both in political [1–2] and lay [3–7] venues. In 1986 the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) mandated that all patients who present to an ED in the United States must receive a medical screening examination, regardless of their ability to pay [8]. The unique role of the ED has prompted some to call it the safety net of the health care system [9–10]. Unfortunately, the increasing problem of crowding has strained this safety net to the “breaking point” according to a recent report by the Institute of Medicine [2,11].

Escalation of the ED crowding problem has prompted researchers to investigate a number of scientific questions, some of which have been summarized by systematic literature reviews. One review characterized the diverse ways in which researchers have defined “overcrowding” [12]. The authors found that the term has been frequently defined using various factors inside and outside of the ED and hospital. They concluded that the crowding research agenda would benefit from a consistent definition. Another review characterized ambulance diversion, whereby an ED advises ambulances to transport patients to other nearby hospitals when possible [13]. The authors found that ambulance diversion is a frequent reaction to ED crowding, which may carry consequences including delayed patient transport and lost hospital revenue.

As noted by the Institute of Medicine, understanding the causes, effects, and solutions of the ED crowding problem is important [2]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous systematic literature review has summarized this research. The objective of this review was to describe the scientific literature on ED crowding from the perspective of causes, effects, and solutions.

Methods

Search Strategy

We adopted the definition of the word “crowding” proposed by the American College of Emergency Physicians [14]: “Crowding occurs when the identified need for emergency services exceeds available resources for patient care in the emergency department, hospital, or both.” From this definition, we interpreted crowding to be a phenomenon that involves the interaction of supply and demand. We defined the scope of this review to include articles that met four criteria: 1) They studied causes, effects, or solutions of crowding as a primary objective. 2) They studied crowding on an empirical basis, with a description of the data collection and analysis methodology. 3) They studied crowding in the context of general emergency medicine, rather than a specialty service like psychiatric emergency medicine. 4) They studied everyday crowding, reflecting a focus on daily surge rather than exceptional circumstances – in other words, they did not study crowding associated with disaster events.

We identified a broad set of PubMed® (MEDLINE®) search terms to encompass each facet of the inclusion criteria. The search involved free text and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH®) terms. We described the concept of “emergency department” by the following search terms: Emergency Medical Services[MeSH] OR Emergency Medicine[MeSH] OR “emergency”. We described the concept of “crowding” by the following search terms: Crowding[MeSH] OR “crowding” OR “crowded” OR “overcrowding” OR “overcrowded” OR “diversion” OR “divert” OR “congestion” OR “surge” OR “capacity” OR “crisis” OR “crises” OR “occupancy”. We queried MEDLINE on June 6, 2006 using the Boolean union of the above queries, restricting the search to English language publications.

Study Selection

Two reviewers (NRH and DA) independently examined the results returned by the MEDLINE search to identify potentially relevant abstracts. Articles that clearly did not meet one or more of the review criteria based on the title and abstract were not considered further. When the two reviewers disagreed, a consensus was reached through discussion. We retrieved full-text articles for the potentially relevant abstracts. The same two reviewers independently examined the full-text articles to determine which studies met all four of the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were again resolved through discussion to reach a final consensus set of articles that met the review criteria.

Data Collection and Processing

We used a data extraction form (online appendix) to record information about the methods and results of each relevant article, including 1) study design, 2) study setting, 3) study population, 4) sample size, 5) independent variables, 6) dependent variables, and 7) primary findings. We assigned the articles to non-exclusive groups according to whether they investigated causes, effects, or solutions of ED crowding. We attempted to represent the intentions of the original authors when assigning each article to a group. For example, an issue like ambulance diversion may be considered a cause, effect, or solution of ED crowding depending on the perspective of each study – it might be a cause of crowding at nearby institutions to which patients are diverted; it might be an effect of crowding at a single institution of interest; or it might be a solution of crowding by reducing the patient load. Within the groups representing causes, effects and solutions of ED crowding, we further categorized articles according to common themes that emerged among the primary findings during the data abstraction phase.

Assessment of Study Quality

To assess the methodological quality of the studies, we applied a previously described five-level instrument [15,16]. While it was originally developed to judge clinical trials, we applied the instrument consistently to clinical trials, descriptive studies, and surveys using the following adaptation: Quality level 1 included prospective studies that studied a clearly defined outcome measure using a random or consecutive sample that was large enough to achieve narrow confidence intervals and diverse enough to suggest generalizability of the findings. Quality level 2 included prospective studies that were more limited in terms of sample size or generalizability. Quality level 3 included retrospective studies that otherwise would have satisfied the criteria for quality levels 1 or 2. Quality level 4 included studies that sampled by convenience or other techniques that were prone to introduce bias. Quality level 5 included studies that lacked a clearly defined or validated outcome measure. We did not score articles that lacked necessary methodological details for the quality instrument.

Results

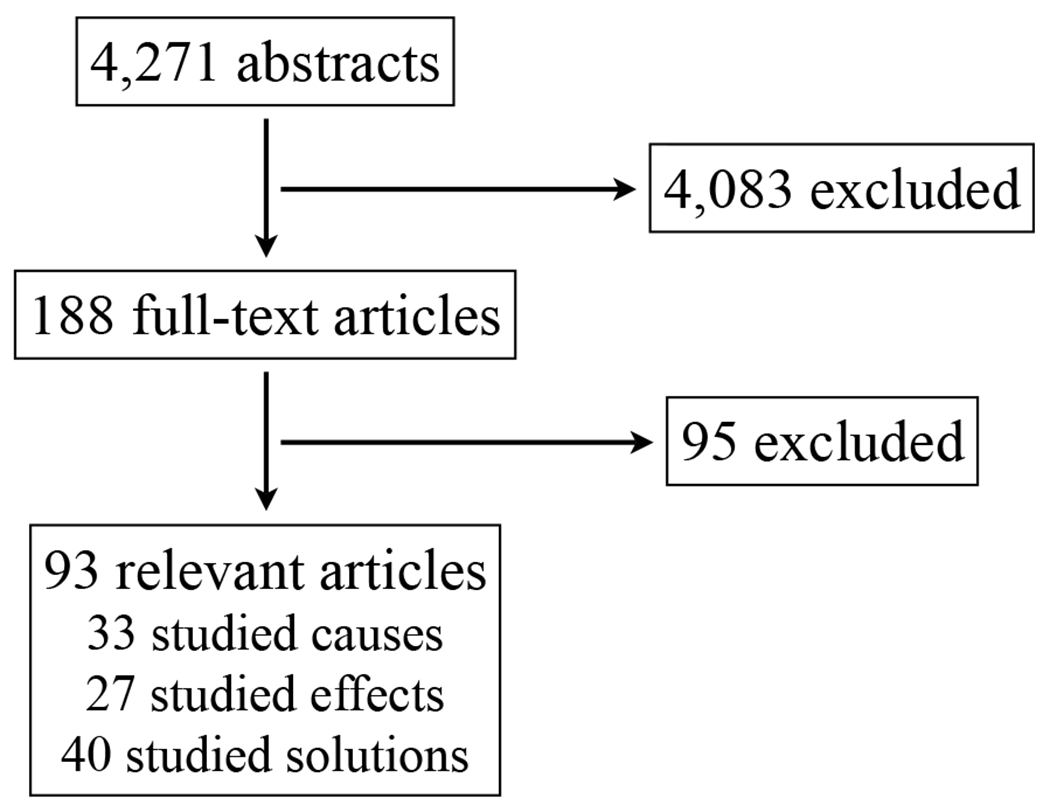

The MEDLINE query returned 4,271 abstracts. The reviewers identified 188 abstracts for full-text retrieval, of which 93 articles satisfied the criteria for inclusion in the review. A flow diagram of the selection process is presented in figure 1. The rate of reviewer agreement during the abstract screening phase, prior to consensus discussion, was 93% overall, 76% among included articles, and 94% among excluded articles. The kappa statistic for chance-corrected agreement between the two reviewers was 0.47 (95% confidence interval: 0.42, 0.52), denoting moderate agreement [17].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process. Articles were defined to be relevant if they 1) studied causes, effects, or solutions of ED crowding as a primary objective; 2) provided a description of the data collection and analysis; 3) took place in a general adult or pediatric ED setting; and 4) focused on everyday crowding instead of disaster-related crowding. Both phases of study selection involved a consensus between two independent reviewers.

We found that quality level 1 contained 14 articles, quality level 2 contained 12 articles, quality level 3 contained 47 articles, quality level 4 contained 10 articles, and quality level 5 contained 6 articles. Four articles were not scored due to inadequate reporting of methodology. The primary findings of all articles are summarized briefly in the following sections. The methods and results of each high-quality prospective study are described in table 1. A total of 33 articles studied causes, 27 articles studied effects, and 40 articles studied solutions of ED crowding. This sum exceeds 93 because some articles were assigned to multiple categories as necessary.

Table 1.

Methods and results of each high-quality prospective study.

| Article | Focus | Design | Sample | Outcome measures | Primary findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Quality level 1 | |||||

| Andersson, 2001 [29] | cause | prospective observational | 16,246 patients over 3 years | waiting time, ED length of stay | ED visits increased from 247.8 to 287.7 per 1000 population, waiting time increased by 8.2 minutes for non-referred patients |

| Bayley, 2005 [70] | effect | prospective cohort | 904 patients | marginal cost | 825 patients boarded more than 3 hours, opportunity cost of $204 per boarding patient, annual total of $168,300 for hospital |

| Burt, 2006 [64] | effect | survey | 405 EDs | ambulance diversion | 16.2 million ambulance transports in United States, 501,000 diversion events annually, 70% from large EDs, 85% response rate |

| Eckstein, 2004 [72] | effect | prospective observational | 21,240 incidents of out-of-service | time to unload patient | 1 in 8 transports took at least 15 minutes to unload patient, increasing over time, more frequent from January to March |

| Fromm, 1993 [39] | cause | prospective cohort | 17,900 visits | ED length of stay | 8.5% of ED patients were critically ill, remained in ED for 145.3 minutes; 154 patient-days of critical care were administered |

| Haines, 2006 [95] | solution | prospective case series | 704 incidents of non-transport | hospital admission rate, patient satisfaction | paramedic decision to not transport pediatric patients led to a 2.4% admission rate, no deaths, good patient satisfaction |

| Lambe, 2003 [32] | cause | prospective observational | 1798 patients | waiting time | waiting times averaged 56 minutes, each $10,000 decrease in local per-capita income increased waiting times by 10.1 minutes |

| Neely, 1994 [56] | effect | prospective observational | 481 patients | transport distance, time | diverted patients traveled 5.0 to 11.6 minutes longer and 1.3 to 4.6 miles further than non-diverted patients |

| Patel, 2006 [91] | solution | before-after intervention | 3 years | ambulance diversion | community-wide diversion policy decreased diversion hours by 74%, despite increases of 6.5% in census and 8.8% in admissions |

| Shah, 2006 [94] | solution | before-after intervention | 2 months | ambulance diversion | destination-control program reduced diversion hours by 41% at a university hospital and 61% at a community hospital |

| Shaw, 1998 [76] | solution | before-after intervention | 48,669 children | elopement, waiting time | additional personnel called on 32% of days, waiting time decreased by 15 minutes, elopement rate decreased by 37% |

| Solberg, 2003 [105] | solution | Delphi method | 74 experts | magnitude estimation | 38 consensus measures of patient demand and complexity; ED capacity, efficiency, and workload; hospital efficiency and capacity |

| Vilke, 2004 [92] | solution | before-after intervention | 2 years | ambulance diversion | standardized diversion guidelines reduced diversion hours from 4,007 to 1,079 and diverted patients from 1,320 to 322 |

| Weiss, 2004 [99] | solution | prospective observational | 336 observations | staff assessments of crowding | NEDOCS predicted crowding assessments with R-squared of 0.49, reduced model retained 88% of accuracy |

|

Quality level 2 | |||||

| Baker, 1991 [67] | effect | prospective cohort | 397 patients | triage assessment, self-reported health status, hospitalization | 46% of patients who left without being seen needed immediate medical attention, 11% were hospitalized in the next week |

| Bindman, 1991 [69] | effect | prospective cohort | 700 patients | waiting time, self-reported health status | 15% of patients left without being seen, 86% due to waiting time, doubled risk of worse pain or disease severity |

| Bucheli, 2004 [74] | solution | before-after intervention | 360 patients | ED length of stay | additional physician during evening shift decreased length of stay from 176 ± 137 to 141 ± 86 minutes for outpatients |

| Fatovich, 2003 [30] | cause | prospective observational | 141 incidents of diversion | reason for ambulance diversion | 30.4% of ambulance diversion incidents caused by entry block, 13.6% by access block, 27.2% by both, 15.2% by high acuity |

| Grumbach, 1993 [19] | cause, solution | survey | 700 patients | reason for visit, willingness to seek alternate care | 45% of patients cited barriers to primary care, 13% had urgent complaints, 38% would trade visit for primary care appointment |

| Kelen, 2001 [78] | solution | before-after intervention | 1,589 patients | elopement, ambulance diversion | acute care unit decreased patient elopement from 10.1% to 5.0% and ambulance diversion from 6.7 to 2.8 hours per 100 patients |

| Michelen, 2006 [96] | solution | before-after intervention | 711 patients | ED utilization | frequent-flyer patients decreased ED usage after primary care referral, health education, and counseling, p < 0.01 for each |

| Raj, 2006 [103] | solution | prospective observational | 128 observations | staff assessments of crowding | mean difference of 3.47 NEDOCS units between NEDOCS and staff assessments, 95% agreement limits of −46.52 to 53.43 |

| Reeder, 2003 [100] | solution | prospective observational | 221 observations | staff assessments of crowding | READI bed ratio differed by 0.245, acuity ratio by 0.131 between periods of normal and excess demand |

| Schneider, 2003 [33] | cause, effect | survey | 250 EDs | operating status at index time | 4.2 patients per nurse, 9.7 patients per physician, 11% of EDs diverting, and 22% of patients boarding, 36% response rate |

| Vilke, 2004 [90] | solution | before-after intervention | 3 weeks | ambulance diversion | frequency of ambulance diversion decreased from 27.7 to 0 hours when nearby hospital smiddleped diverting ambulances |

| Washington, 2002 [85] | solution | randomized controlled trial | 156 patients | self-reported health status, care utilization | patients with three symptom complexes deferred to next-day care had similar health status and care utilization at follow-up |

ED = emergency department; NEDOCS = National Emergency Department Overcrowding Scale; READI = Real-time Emergency Analysis of Demand Indicators

Causes

Three general themes existed among the causes of ED crowding: input factors, throughput factors, and output factors. These themes correspond to a conceptual framework for studying ED crowding [18]. Input factors reflected sources and aspects of patient inflow. Throughput factors reflected bottlenecks within the ED. Output factors reflected bottlenecks in other parts of the health care system that might affect the ED. The commonly studied causes of crowding are summarized in table 2.

Table 2.

Commonly studied causes of ED crowding.

Input factors.

We identified non-urgent visits, frequent-flyer patients, and the influenza season to be commonly studied input factors that may cause crowding.

Four articles considered non-urgent visits: Three studies found that low-acuity ED patients frequently sought non-urgent care in the ED, and their reasons for doing so included insufficient or untimely access to primary care [19–21]. However, one analysis suggested that visits by patients with non-urgent complaints were not associated with the most severe crowding at large hospitals [22].

Two articles studied frequent-flyer patients: One report found that frequent visitors, defined by four or more annual visits, accounted for 14% of the total ED visits [23]. Moreover, these patients generally did not have urgent complaints and exhibited Andersen’s “need factors” for health care [24]. A similar report found that the 500 most frequent users of one ED accounted for 8% of total visits, and 29% of these visits might have been appropriate for primary care [25].

Three articles investigated the influenza season: Los Angeles County hospitals recorded a four-to-seven fold increase in ambulance diversion during the peak four weeks of flu season, as compared to other times of the year [26]. In Toronto, every 10 local cases of flu resulted in a 1.5% increase in the fraction of ED visitors who were elderly flu patients [27]. The same group in Toronto calculated that every 100 local cases of flu resulted in an increase of 2.5 hours per week of ambulance diversion [28].

Four articles examined other aspects of input factors: Stockholm experienced a 21% increase in ED visits over a four-year span, far exceeding the population growth of 4.5% during the same period; the authors attributed this to two hospital closures that caused the ED to become more responsible for primary care delivery [29]. One study estimated that excess patient volume prompted 71% of ambulance diversion episodes, and excess patient acuity prompted 15% of ambulance diversion episodes [30]. Although recently discharged inpatients accounted for just 3% of total visits to one ED, they had longer lengths of stay and more frequent hospital admissions than other patients [31]. California EDs that were located in neighborhoods of lower socioeconomic status had increased waiting times, estimated to be 10 minutes longer per $10,000 reduction in per capita income [32].

Throughput factors.

We identified inadequate staffing to be a commonly studied throughput factor that may cause crowding.

Three articles discussed inadequate staffing: A point prevalence study of crowding found that the average nurse was caring for 4 patients simultaneously, and the average physician was caring for 10 patients simultaneously [33]. A study in California showed that lower staffing levels of physicians and triage nurses predisposed patients to wait longer for care [32]. By contrast, a time series analysis indicated that, after controlling for other factors, ambulance diversion was not associated with physician and nurse staffing levels [34].

Three articles discussed other aspects of throughput factors: During a nine-year period, the number of California EDs decreased by 12% while the number of ED beds increased by 16% [35]. This may not have been sufficient considering that the number of visits and critical visits per ED increased by 27% and 59%, respectively, during the same period. The training background of the attending in charge of an ED has been independently associated with patients leaving without being seen [36]. The use of ancillary services, including computed tomography (CT) scanning and other procedures, prolonged the ED length of stay among surgical critical care patients [37].

Output factors.

We identified inpatient boarding and hospital bed shortages to be commonly studied output factors that may cause crowding.

Five articles studied inpatient boarding: One study found that half of EDs in the United States reported extending boarding times for patients in the ED [38]. A point prevalence study found that 22% of all ED patients were boarding at one time [33]. One academic ED delivered 154 patient-days of care to critically ill patients over a one-year period [39]. Patients experiencing access block, defined by boarding time exceeding eight hours, was associated with increased diversion, waiting times, and occupancy level in an Australian ED [40]. A time series analysis showed that the number of boarding patients was independently associated with the frequency of ambulance diversion [34].

Six articles examined hospital bed shortages: A study of English accident and emergency trusts found a strong correlation between ED treatment time and hospital occupancy [41]. A period of widespread hospital restructuring in Toronto independently increased the rate of severe overcrowding from 0.5% to 6% of the time [42]. Length of stay in one ED increased substantially when the hospital occupancy levels exceeded 90% [43]. A survey of Korean EDs linked high hospital occupancy levels to ED crowding [44]. A study in Portland found that a decrease in hospital beds was strongly associated with an increase in ambulance diversion [45]. Another study estimated that a hospital closure would affect the nearest ED by increasing ambulance diversion by 56 hours per month for four months [46].

Additional themes.

Five surveys and interviews identified factors that health care providers and other stakeholders perceive to be important causes of ED crowding: increasing patient volume and acuity, shortages of treatment areas, shortages of nursing staff, delays in ancillary services, boarding inpatients, and hospital bed shortages [47–51].

Effects

Four general themes existed among the effects of ED crowding: adverse outcomes, reduced quality, and impaired access, and provider losses. Adverse outcomes reflected health-related patient endpoints. Reduced quality reflected benchmarks of the care delivery process. Impaired access reflected the ability of patients to receive timely care at their preferred institutions. Provider losses reflected consequences borne by the health care system itself. The commonly studied effects of crowding are summarized in table 3.

Table 3.

Commonly studied effects of ED crowding.

Adverse outcomes.

We identified patient mortality to be a commonly studied adverse outcome of crowding.

Four articles focused on patient mortality: One study found a significant increase in mortality associated with weekly ED volume [52]. High occupancy in one Australian ED was estimated to cause 13 patient deaths per year [53]. Another study associated a combined measure of hospital and ED crowding with an increased risk of mortality at 2, 7, and 30 days following hospital admission [54]. In Houston, a statistically insignificant trend was found for higher mortality among trauma patients who were admitted during ambulance diversion [55].

Reduced quality.

We identified transport delays and treatment delays to be commonly studied effects of crowding pertaining to reduced quality.

Four articles examined transport delays: Ambulance diversion was shown to increase transport time and distance in two studies [56–57]. A study focused on cardiac patients found that the 90th percentile of transport time increased when multiple local hospitals were on diversion [58]. During two years in which crowding was exacerbated in Toronto, the 90th percentile of transport time increased by 11% [59].

Four articles investigated treatment delays: Patients who arrived at one ED during crowded periods waited 30 minutes longer for an ED bed [60]. Crowding was associated with increased door-to-needle time for patients with suspected myocardial infarction [61]. High ED occupancy levels were associated with delayed pain assessment and lower likelihood of pain documentation among hip fracture patients [62]. A negative trial found no increase in the time to head computed tomography among suspected stroke patients when a trauma evaluation occurred simultaneously [63].

Impaired access.

We identified ambulance diversion and patient elopement to be commonly studied effects of crowding pertaining to impaired access.

Two articles focused on ambulance diversion: A national survey found that approximately 501,000 ambulance diversions occurred in the United States during one year, and approximately 70% of these were from large EDs [64]. A point prevalence study of ED crowding found that 11% of United States EDs were simultaneously diverting ambulances [33].

Six articles characterized patient elopement: Patients were more likely to leave without being seen when ED occupancy exceeded 100% of the total capacity [36]. In one study, the rate of patients leaving without being seen closely correlated with waiting times [65]. The rate of patients leaving one ED without being seen correlated well with a crowding regression model [66]. Among patients who left without being seen, 46% needed urgent medical attention, and 11% were hospitalized within a week [67]. Patients frequently cited long waiting times as a reason for leaving without being seen, and 60% of them sought other medical care within a week [68]. Patients who left the ED without being seen were twice as likely to report worsened health problems [69].

Provider losses.

We identified financial impact to be a commonly studied provider loss of crowding.

Two articles calculated financial impact: One study estimated that the hospital lost $204 in potential revenue per patient with an extended boarding time [70]. Another study found that patients who boarded in the ED longer than a day also stayed in the hospital longer, increasing costs by an estimated $6.8 million over three years [71].

Two articles considered other aspects of provider losses: A study found that during one in eight patient transports, the ambulance could not unload the patient promptly at the ED, putting it out of service for 15 minutes or more [72]. A survey of Canadian emergency physicians found that job dissatisfaction was closely related to the perceived scarcity of resources [73].

Additional themes.

Three surveys identified outcomes that ED directors perceive to be major effects of crowding: death, delayed care, unnecessary procedures, and extended pain [47–49].

Solutions

Three general themes existed among the solutions of ED crowding: increased resources, demand management, and operations research. Increased resources reflected the deployment of additional physical, personnel, and supporting resources. Demand management reflected methods to redistribute patients or encourage appropriate utilization. Operations research reflected crowding measures and offline change management techniques. The commonly studied solutions of crowding are summarized in table 4.

Table 4.

Commonly studied solutions of ED crowding.

| Solution of crowding | References |

|---|---|

| Increased resources | |

| Additional personnel | [74–76] |

| Observation units | [77–80] |

| Hospital bed access | [81–82] |

| Demand management | |

| Non-urgent referrals | [19,85–87] |

| Ambulance diversion | [88–92] |

| Destination control | [93–94] |

| Operations research | |

| Crowding measures | [98–105] |

| Queuing theory | [106–107] |

Increased resources.

We identified additional personnel, observation units, and hospital bed access to be commonly studied solutions of crowding involving increased resources.

Three articles studied additional personnel: One described a permanent increase in the number of physicians during a busy shift, reducing the outpatient length of stay by 35 minutes [74]. A rural hospital, which previously did not have an attending physician present during the night shift, found that the presence of an attending physician improved several throughput measures of ED crowding [75]. One hospital activated reserve personnel on an as-needed basis during the viral epidemic season, reducing the waiting time by 15 minutes and the rate of patients leaving without being seen by 37% [76].

Four articles investigated observation units: One short-stay medicine unit reduced the length of stay for outpatients with chest pain and asthma exacerbation [77]. Another study found that an ED-managed acute care unit decreased ambulance diversion by 40% and halved the rate of patients leaving without being seen [78]. A hospital reported that the addition of an acute medical unit reduced the median number of boarding patients from 14 to 8 over a 2-year period [79]. One study proposed a hybrid observation unit, which was designed to use resources effectively and substantially decreased the length of stay for scheduled procedure patients [80].

Two articles considered hospital bed access: After increasing the number of critical care beds from 47 to 67, ambulance diversion at one hospital decreased by 66% [81]. A natural experiment resulting from a period of industrial action, leading to improved hospital bed access for an ED, resulted in significant decreases in occupancy levels and waiting times [82].

Two articles examined other aspects of increased resources: One study increased both space and staffing through an ED reorganization, which resulted in the improvement of several crowding outcomes [83]. Another study attempted to reduce the potential bottleneck of ancillary services by implementing point-of-care laboratory testing, which decreased the length of stay by 41 minutes [84].

Demand management.

We identified non-urgent referrals, ambulance diversion, and destination control to be commonly studied solutions of crowding involving demand management.

Four studies tested non-urgent referrals: A survey of ED patients found that 38% would swap their ED visit for a primary care appointment within 72 hours [19]. A randomized, controlled trial focused on three common symptom complexes and found that they may be deferred for next-day primary care without worsening self-reported health status on follow-up [85]. When following up non-urgent patients who were triaged to receive care elsewhere, one group found that there were no major adverse outcomes, and 42% of the patients received same-day care elsewhere [86]. A similar study found that 94% of non-urgent patients who were referred to community-based care reported that their condition was better or unchanged [87].

Five studies investigated ambulance diversion: By one calculation, ambulance diversion decreased the rate of ambulance arrivals by 30% to 50% [88]. A similar calculation found that “red-alert” ambulance diversion reduced the arrival rate by 0.4 per hour [89]. When one hospital committed to avoiding ambulance diversion for one week, the need for diversion at a nearby hospital was almost eliminated [90]. Standardized diversion criteria in Sacramento, targeted to decrease “round-robin” crowding, reduced the rate of ambulance diversion by 74% in spite of increased patient volume [91]. San Diego implemented a standardized policy for initiating ambulance diversion among all local hospitals and reduced ambulance diversion by 75% [92].

Two studies proposed destination control: The use of Internet-accessible operating information to redistribute ambulances reduced the need for diversion from 1788 hours to 1138 hours in one network [93]. Another study described a physician-directed ambulance destination control initiative that reduced diversion by 41% [94].

Three studies considered other aspects of demand management: A trial of paramedic-initiated non-transport found that 2.4% of non-transported pediatric patients were later admitted to the hospital [95]. Three social interventions designed for frequent visitors, which included education and counseling, were associated with decreased ED utilization [96]. Another study targeted frequent users with case management interventions, but the rate of ED utilization was unchanged [97].

Operations research.

The studies within the operations research theme did not describe direct solutions to ED crowding; however, they proposed to support solutions through improved business intelligence. We identified crowding measures and queuing theory to be commonly studied solutions to crowding based on operations research.

Eight studies described crowding measures: The Emergency Department Work Index (EDWIN) associated well with ambulance diversion and less well with secondary outcome measures at its institution of origin [98]. The National Emergency Department Overcrowding Scale (NEDOCS) explained 49% of the variation in physician and nurse assessments of crowding [99]. The Real-time Emergency Analysis of Demand Indicators (READI) were designed for real-time monitoring of ED operations, although they did not correlate with providers’ opinions on crowding [100]. The Work Score predicted ambulance diversion at its institution of origin with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.89 [101]. A comparative validation, which employed staff assessments of crowding as the outcome, estimated the AUC of the EDWIN to be 0.80 and of the NEDOCS to be 0.83 [102]. However, an external validation of the NEDOCS in Australia concluded that it was not useful, based on Bland-Altman and kappa statistics [103]. A sampling form consisting of seven operational measures was shown to correlate well with staff assessments of crowding [104]. A panel of experts described 38 consensus operational measures that may be used to assess crowding levels [105].

Two studies employed queuing theory: One group illustrated the ability of discrete event simulation to model ED operations, and they tested its applicability by analyzing a proposed triage scheme [106]. A similar study described a separate discrete event simulation and studied the effects of physician utilization on patient waiting times [107].

Additional themes.

Five studies described multi-faceted administrative interventions that could not be classified separately: A broad intervention consisting of 51 actions reduced ED length of stay and ambulance diversion in Melbourne [108]. One network deployed several interventions, tuned for the individual needs of four hospitals, and reduced the amount of ambulance diversion by 25% and 34% in consecutive years [109]. A group of hospitals in Rochester deployed several interventions, and they reported that the most effective interventions occurred outside the ED [110]. Another study reported interventions, including more physicians, improved ancillary services, and changes in hospital policy, that reduced length of stay by half [111]. One hospital deployed a multi-pronged intervention, which involved a short-stay unit, additional physicians, and an early warning system, to deal with holiday demand surges [112].

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations that merit discussion. First, we may not have captured every article that studied causes, effects, and solutions of ED crowding. We limited the search to English-language articles, so any relevant articles published in foreign languages were not included. We avoided searching the grey literature using a general-purpose internet query, and we did not hand-search the references of included articles. If used, these two techniques might have impaired the reproducibility of our review. We searched a single database; moreover, it is possible that our search terms did not capture all aspects of the topic. The MeSH vocabulary contains a single term related to crowding, so we supplemented the search with a large set of free text keywords. We attempted to minimize the likelihood of missed articles by applying a broad search strategy. We also used a conservative approach during the abstract screening phase, retrieving the full-text articles for all abstracts that could not be clearly excluded. The moderate kappa value may be explained because one author was more conservative than the other in marking abstracts for full-text retrieval. This issue was identified and resolved during the consensus discussion. We believe our methodology captured the substantial majority of pertinent articles.

Second, the diversity of methodology, outcome measures, and reporting among the original articles rendered aspects of this review difficult. We attempted to describe the primary findings of each study as consistently as possible – noting the effect sizes of each study when feasible, and in other cases describing the nature of the findings in more qualitative terms. In some cases, our descriptions were limited according to the reporting of the original articles. The brief summaries that we provide do not capture the full complexity of each study, so our review is intended to guide interested readers to the original cited articles. We did not conduct a formal meta-analysis, due to the breadth of study designs and endpoints considered. We refrain from making strong conclusions about which factors are most important, because these would be based primarily on judgment rather than numerical inference.

Third, the classification of studies into groups and themes was partly subjective, so objections may be made regarding how particular articles were categorized. We acknowledge that there may be no clearly correct taxonomy for grouping this diverse set of articles. For instance, measurement tools and queuing models would not reduce ED crowding unless paired with an intervention plan. Regardless, we have classified these articles as solutions, insofar as the original authors intended their research to support crowding interventions. Our intention in using this trichotomy of causes, effects, and solutions was to provide a structured overview of the relevant literature, which we hope benefits the reader.

Discussion

A substantial body of literature exists describing the causes, effects, and solutions of ED crowding. The major themes among the causes of crowding included non-urgent visits, frequent-flyer patients, influenza season, inadequate staffing, inpatient boarding, and hospital bed shortages. The major themes among the effects of crowding included patient mortality, transport delays, treatment delays, ambulance diversion, patient elopement, and financial impact. The major themes among the solutions of crowding included additional personnel, observation units, hospital bed access, non-urgent referrals, ambulance diversion, destination control, crowding measures, and queuing theory.

The quality instrument that we employed indicated that a large number of high-quality articles have been published regarding ED crowding [15,16]. We identified a total of 26 prospective studies and 47 retrospective studies that met the criteria for the three highest quality levels. We noted a scarcity of randomized controlled trials in this review, perhaps because many ED operational changes involve the entire department, rather than individual patients who may be randomized to experimental and control groups [85]. We believe that the crowding literature would benefit from more randomized controlled trials examining patient-focused interventions.

Although several studies investigated non-urgent and frequent-flyer visits, relatively little evidence suggests they independently cause ED crowding [19–23,25]. This notion is supported by recent literature [113]. More evidence is available to identify inpatient boarding and other hospital-related factors as causes of ED crowding [33–34,38–46]. These studies corroborate with successful interventions that reduced crowding by altering the operation of hospital and community services other than the ED [78–79,81–82,90–93]. We believe that the crowding literature would benefit from more studies that 1) analyze the ED in the context of integrated hospital processes and 2) focus on multi-center community networks rather than single institutions.

The results suggest that standard operations management tools, such as queuing theory, have only recently been applied in an effort to improve ED patient flow [106–107]. We are aware of few prior reports describing such applications in the ED setting [114]. By contrast, these tools were adopted much earlier by industries like airlines and manufacturing. This lag is analogous to the gap between basic science and clinical science, which translational research aims to address. A result of queuing theory states that a system with varying inputs and fixed capacity will become congested for transient periods of time [115]. By consequence, permanent increases in resources may be neither efficient nor adequate to address crowding given the fluctuating demand. The review includes one study demonstrating the feasibility of deploying additional resources on demand to alleviate ED crowding [76]. We believe that the crowding literature would benefit from studies that 1) apply standard management research techniques to ED operations and 2) investigate ways to alter resource availability dynamically based on demand.

When considered as a whole, the body of literature demonstrates that ED crowding is a local manifestation of a systemic disease. The causes of ED crowding involve a complex network of interwoven processes ranging from hospital workflow to viral epidemics. The effects of ED crowding are numerous and adverse. Various targeted solutions to crowding have been shown to be effective, and further studies may demonstrate new innovations. This broad overview of the current research may help to inform the future research agenda and, subsequently, to protect the fragile safety net of the health care system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first author was supported by the National Library of Medicine grant LM07450-02 and National Institute of General Medical Studies grant T32 GM07347. The research was also supported by the National Library of Medicine grant R21 LM009002-01.

References

- [1].Yamane K Hospital emergency departments: crowded conditions vary among hospitals and communities. Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Accounting Office; 2003. GAO-03-460. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-based emergency care: at the breaking point. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gibbs N Do you want to die? The crisis in emergency care is taking its toll on doctors, nurses, and patients. Time. May 28, 1990:58–65. [PubMed]

- [4].Barrero J Hospitals get orders to reduce crowding in emergency rooms. New York Times. January 24, 1989:1–2.

- [5].Goldberg C Emergency crews worry as hospitals say, “No vacancy.” New York Times. December 17, 2000:39.

- [6].Orenstein JB. State of emergency. Washington Post. April 22, 2001:B1.

- [7].Jeffrey NA. Who’s crowding emergency rooms? Right now it’s managed-care patients. Wall Street J. July 20, 1999:B1. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act, established under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985. Pub L No. 99-272, 42USC 1395dd (1986).

- [9].Asplin BR. Tying a knot in the unraveling health care safety net. Acad Emerg Med. 2001. November;8(11):1075–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Overcrowding crisis in our nation’s emergency departments: is our safety net unraveling? Pediatrics. 2004. September;114(3):878–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kellermann AL. Crisis in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006. September 28;355(13):1300–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hwang U, Concato J. Care in the emergency department: how crowded is overcrowded? Acad Emerg Med. 2004. October;11(10):1097–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pham JC, Patel R, Millin MG, Kirsch TD, Chanmugam A. The effects of ambulance diversion: a comprehensive review. Acad Emerg Med. 2006. November;13(11):1220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].American College of Emergency Physicians. Crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2006. June;47(6):585. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, et al. Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. 2nd ed. Boston: Little Brown; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang CS, FitzGerald JM, Schulzer M, Mak E, Ayas NT. Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure? JAMA. 2005. October 19;294(15):1944–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, et al. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2003. August;42(2):173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Grumbach K, Keane D, Bindman A. Primary care and public emergency department overcrowding. Am J Public Health. 1993. March;83(3):372–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Afilalo J, Marinovich A, Afilalo M, et al. Nonurgent emergency department patient characteristics and barriers to primary care. Acad Emerg Med. 2004. December;11(12):1302–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Howard MS, Davis BA, Anderson C, et al. Patients’ perspective on choosing the emergency department for nonurgent medical care: a qualitative study exploring one reason for overcrowding. J Emerg Nurs. 2005. October;31(5):429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sprivulis P, Grainger S, Nagree Y. Ambulance diversion is not associated with low acuity patients attending Perth metropolitan emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas. 2005. February;17(1):11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huang JA, Tsai WC, Chen YC, et al. Factors associated with frequent use of emergency services in a medical center. J Formos Med Assoc. 2003. April;102(4):222–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995. March;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dent AW, Phillips GA, Chenhall AJ, et al. The heaviest repeat users of an inner city emergency department are not general practice patients. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2003. August;15(4):322–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Glaser CA, Gilliam S, Thompson WW, et al. Medical care capacity for influenza outbreaks, Los Angeles. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002. June;8(6):569–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schull MJ, Mamdani MM, Fang J. Influenza and emergency department utilization by elders. Acad Emerg Med. 2005. April;12(4):338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schull MJ, Mamdani MM, Fang J. Community influenza outbreaks and emergency department ambulance diversion. Ann Emerg Med. 2004. July;44(1):61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Andersson G, Karlberg I. Lack of integration, and seasonal variations in demand explained performance problems and waiting times for patients at emergency departments: a 3 years evaluation of the shift of responsibility between primary and secondary care by closure of two acute hospitals. Health Policy. 2001. March;55(3):187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fatovich DM, Hirsch RL. Entry overload, emergency department overcrowding, and ambulance bypass. Emerg Med J. 2003. September;20(5):406–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Baer RB, Pasternack JS, Zwemer FL Jr. Recently discharged inpatients as a source of emergency department overcrowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2001. November;8(11):1091–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lambe S, Washington DL, Fink A, et al. Waiting times in California’s emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2003. January;41(1):35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schneider SM, Gallery ME, Schafermeyer R, et al. Emergency department crowding: a point in time. Ann Emerg Med. 2003. August;42(2):167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schull MJ, Lazier K, Vermeulen M, et al. Emergency department contributors to ambulance diversion: a quantitative analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2003. April;41(4):467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lambe S, Washington DL, Fink A, et al. Trends in the use and capacity of California’s emergency departments, 1990–1999. Ann Emerg Med. 2002. April;39(4):389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Polevoi SK, Quinn JV, Kramer NR. Factors associated with patients who leave without being seen. Acad Emerg Med. 2005. March;12(3):232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Davis B, Sullivan S, Levine A, et al. Factors affecting ED length-of-stay in surgical critical care patients. Am J Emerg Med. 1995. September;13(5):495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Andrulis DP, Kellermann A, Hintz EA, et al. Emergency departments and crowding in United States teaching hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 1991. September;20(9):980–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fromm RE Jr, Gibbs LR, McCallum WG, et al. Critical care in the emergency department: a time-based study. Crit Care Med. 1993. July;21(7):970–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fatovich DM, Nagree Y, Sprivulis P. Access block causes emergency department overcrowding and ambulance diversion in Perth, Western Australia. Emerg Med J. 2005. May;22(5):351–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cooke MW, Wilson S, Halsall J, et al. Total time in English accident and emergency departments is related to bed occupancy. Emerg Med J. 2004. September;21(5):575–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schull MJ, Szalai JP, Schwartz B, et al. Emergency department overcrowding following systematic hospital restructuring: trends at twenty hospitals over ten years. Acad Emerg Med. 2001. November;8(11):1037–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Forster AJ, Stiell I, Wells G, et al. The effect of hospital occupancy on emergency department length of stay and patient disposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2003. February;10(2):127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hwang JI. The relationship between hospital capacity characteristics and emergency department volumes in Korea. Health Policy. 2006. December;79(2–3):274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Warden CR, Bangs C, Norton R, et al. Temporal trends in ambulance diversion in a mid-sized metropolitan area. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2003. Jan-Mar;7(1):109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sun BC, Mohanty SA, Weiss R, et al. Effects of hospital closures and hospital characteristics on emergency department ambulance diversion, Los Angeles County, 1998 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med. 2006. April;47(4):309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Derlet RW, Richards JR. Emergency department overcrowding in Florida, New York, and Texas. South Med J. 2002. August;95(8):846–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Derlet R, Richards J, Kravitz R. Frequent overcrowding in U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2001. February;8(2):151–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Richards JR, Navarro ML, Derlet RW. Survey of directors of emergency departments in California on overcrowding. West J Med. 2000. June;172(6):385–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Clark K, Normile LB. Delays in implementing admission orders for critical care patients associated with length of stay in emergency departments in six mid-Atlantic states. J Emerg Nurs. 2002. December;28(6):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bazzoli GJ, Brewster LR, Liu G, et al. Does U.S. hospital capacity need to be expanded? Health Aff (Millwood). 2003. Nov-Dec;22(6):40–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Miro O, Antonio MT, Jimenez S, et al. Decreased health care quality associated with emergency department overcrowding. Eur J Emerg Med. 1999. June;6(2):105–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006. March 6;184(5):213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sprivulis PC, Da Silva JA, Jacobs IG, et al. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Med J Aust. 2006. March 6;184(5):208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Begley CE, Chang Y, Wood RC, et al. Emergency department diversion and trauma mortality: evidence from Houston, Texas. J Trauma. 2004. December;57(6):1260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Neely KW, Norton RL, Young GP. The effect of hospital resource unavailability and ambulance diversions on the EMS system. Prehospital Disaster Med. 1994. Jul-Sep;9(3):172–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Redelmeier DA, Blair PJ, Collins WE. No place to unload: a preliminary analysis of the prevalence, risk factors, and consequences of ambulance diversion. Ann Emerg Med. 1994. January;23(1):43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Schull MJ, Morrison LJ, Vermeulen M, et al. Emergency department gridlock and out-of-hospital delays for cardiac patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2003. July;10(7):709–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schull MJ, Morrison LJ, Vermeulen M, et al. Emergency department overcrowding and ambulance transport delays for patients with chest pain. CMAJ. 2003. February 4;168(3):277–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Liu S, Hobgood C, Brice JH. Impact of critical bed status on emergency department patient flow and overcrowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2003. April;10(4):382–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Schull MJ, Vermeulen M, Slaughter G, et al. Emergency department crowding and thrombolysis delays in acute myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg Med. 2004. December;44(6):577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hwang U, Richardson LD, Sonuyi TO, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on the management of pain in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006. February;54(2):270–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Chen EH, Mills AM, Lee BY, et al. The impact of a concurrent trauma alert evaluation on time to head computed tomography in patients with suspected stroke. Acad Emerg Med. 2006. March;13(3):349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Burt CW, McCaig LF, Valverde RH. Analysis of ambulance transports and diversions among US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006. April;47(4):317–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kyriacou DN, Ricketts V, Dyne PL, et al. A 5-year time study analysis of emergency department patient care efficiency. Ann Emerg Med. 1999. September;34(3):326–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Weiss SJ, Ernst AA, Derlet R, et al. Relationship between the National ED Overcrowding Scale and the number of patients who leave without being seen in an academic ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2005. May;23(3):288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Baker DW, Stevens CD, Brook RH. Patients who leave a public hospital emergency department without being seen by a physician. Causes and consequences. JAMA. 1991. August 28;266(8):1085–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Rowe BH, Channan P, Bullard M, et al. Characteristics of patients who leave emergency departments without being seen. Acad Emerg Med. 2006. August;13(8):848–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Keane D, et al. Consequences of queuing for care at a public hospital emergency department. JAMA. 1991. August 28;266(8):1091–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Bayley MD, Schwartz JS, Shofer FS, et al. The financial burden of emergency department congestion and hospital crowding for chest pain patients awaiting admission. Ann Emerg Med. 2005. February;45(2):110–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Krochmal P, Riley TA. Increased health care costs associated with ED overcrowding. Am J Emerg Med. 1994. May;12(3):265–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Eckstein M, Chan LS. The effect of emergency department crowding on paramedic ambulance availability. Ann Emerg Med. 2004. January;43(1):100–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Rondeau KV, Francescutti LH. Emergency department overcrowding: the impact of resource scarcity on physician job satisfaction. J Healthc Manag. 2005. Sep-Oct;50(5):327–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Bucheli B, Martina B. Reduced length of stay in medical emergency department patients: a prospective controlled study on emergency physician staffing. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004. February;11(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Donald KJ, Smith AN, Doherty S, et al. Effect of an on-site emergency physician in a rural emergency department at night. Rural Remote Health. 2005. Jul-Sep;5(3):380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Shaw KN, Lavelle JM. VESAS: a solution to seasonal fluctuations in emergency department census. Ann Emerg Med. 1998. December;32(6):698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Bazarian JJ, Schneider SM, Newman VJ, et al. Do admitted patients held in the emergency department impact the throughput of treat-and-release patients? Acad Emerg Med. 1996. December;3(12):1113–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Kelen GD, Scheulen JJ, Hill PM. Effect of an emergency department (ED) managed acute care unit on ED overcrowding and emergency medical services diversion. Acad Emerg Med. 2001. November;8(11):1095–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Moloney ED, Bennett K, O’Riordan D, et al. Emergency department census of patients awaiting admission following reorganisation of an admissions process. Emerg Med J. 2006. May;23(5):363–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ross MA, Naylor S, Compton S, et al. Maximizing use of the emergency department observation unit: a novel hybrid design. Ann Emerg Med. 2001. March;37(3):267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].McConnell KJ, Richards CF, Daya M, et al. Effect of increased ICU capacity on emergency department length of stay and ambulance diversion. Ann Emerg Med. 2005. May;45(5):471–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Dunn R Reduced access block causes shorter emergency department waiting times: An historical control observational study. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2003. June;15(3):232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Miro O, Sanchez M, Espinosa G, et al. Analysis of patient flow in the emergency department and the effect of an extensive reorganisation. Emerg Med J. 2003. March;20(2):143–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Lee-Lewandrowski E, Corboy D, Lewandrowski K, et al. Implementation of a point-of-care satellite laboratory in the emergency department of an academic medical center. Impact on test turnaround time and patient emergency department length of stay. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003. April;127(4):456–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Washington DL, Stevens CD, Shekelle PG, et al. Next-day care for emergency department users with nonacute conditions. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2002. November 5;137(9):707–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Derlet RW, Nishio D, Cole LM, et al. Triage of patients out of the emergency department: three-year experience. Am J Emerg Med. 1992. May;10(3):195–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Diesburg-Stanwood A, Scott J, Oman K, et al. Nonemergent ED patients referred to community resources after medical screening examination: characteristics, medical condition after 72 hours, and use of follow-up services. J Emerg Nurs. 2004. August;30(4):312–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Lagoe RJ, Hunt RC, Nadle PA, et al. Utilization and impact of ambulance diversion at the community level. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002. Apr-Jun;6(2):191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Scheulen JJ, Li G, Kelen GD. Impact of ambulance diversion policies in urban, suburban, and rural areas of Central Maryland. Acad Emerg Med. 2001. January;8(1):36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Vilke GM, Brown L, Skogland P, et al. Approach to decreasing emergency department ambulance diversion hours. J Emerg Med. 2004. February;26(2):189–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Patel PB, Derlet RW, Vinson DR, et al. Ambulance diversion reduction: the Sacramento solution. Am J Emerg Med. 2006. March;24(2):206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Vilke GM, Castillo EM, Metz MA, et al. Community trial to decrease ambulance diversion hours: the San Diego county patient destination trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2004. October;44(4):295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Sprivulis P, Gerrard B. Internet-accessible emergency department workload information reduces ambulance diversion. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005. Jul-Sep;9(3):285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Shah MN, Fairbanks RJ, Maddow CL, et al. Description and evaluation of a pilot physician-directed emergency medical services diversion control program. Acad Emerg Med. 2006. January;13(1):54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Haines CJ, Lutes RE, Blaser M, et al. Paramedic initiated non-transport of pediatric patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006. Apr-Jun;10(2):213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Michelen W, Martinez J, Lee A, et al. Reducing frequent flyer emergency department visits. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006. February;17(1 Suppl):59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lee KH, Davenport L. Can case management interventions reduce the number of emergency department visits by frequent users? Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2006. Apr-Jun;25(2):155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Bernstein SL, Verghese V, Leung W, et al. Development and validation of a new index to measure emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2003. September;10(9):938–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Weiss SJ, Derlet R, Arndahl J, et al. Estimating the degree of emergency department overcrowding in academic medical centers: results of the National ED Overcrowding Study (NEDOCS). Acad Emerg Med. 2004. January;11(1):38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Reeder TJ, Burleson DL, Garrison HG. The overcrowded emergency department: a comparison of staff perceptions. Acad Emerg Med. 2003. October;10(10):1059–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Epstein SK, Tian L. Development of an emergency department work score to predict ambulance diversion. Acad Emerg Med. 2006. April;13(4):421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Weiss SJ, Ernst AA, Nick TG. Comparison of the National Emergency Department Overcrowding Scale and the Emergency Department Work Index for quantifying emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2006. May;13(5):513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Raj K, Baker K, Brierley S, et al. National Emergency Department Overcrowding Study tool is not useful in an Australian emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2006. June;18(3):282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Weiss SJ, Arndahl J, Ernst AA, et al. Development of a site sampling form for evaluation of ED overcrowding. Med Sci Monit. 2002. August;8(8):CR549–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Solberg LI, Asplin BR, Weinick RM, et al. Emergency department crowding: consensus development of potential measures. Ann Emerg Med. 2003. December;42(6):824–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Connelly LG, Bair AE. Discrete event simulation of emergency department activity: a platform for system-level operations research. Acad Emerg Med. 2004. November;11(11):1177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Chin L, Fleisher G. Planning model of resource utilization in an academic pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998. February;14(1):4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Cameron P, Scown P, Campbell D. Managing access block. Aust Health Rev. 2002;25(4):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Lagoe RJ, Kohlbrenner JC, Hall LD, et al. Reducing ambulance diversion: a multihospital approach. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2003. Jan-Mar;7(1):99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Schneider S, Zwemer F, Doniger A, et al. Rochester, New York: a decade of emergency department overcrowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2001. November;8(11):1044–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Cardin S, Afilalo M, Lang E, et al. Intervention to decrease emergency department crowding: does it have an effect on return visits and hospital readmissions? Ann Emerg Med. 2003. February;41(2):173–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Salazar A, Corbella X, Sanchez JL, et al. How to manage the ED crisis when hospital and/or ED capacity is reaching its limits. Report about the implementation of particular interventions during the Christmas crisis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2002. March;9(1):79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Schull MJ, Kiss A, Szalai JP. The effect of low-complexity patients on emergency department waiting times. Ann Emerg Med. 2007. March;49(3):257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Siddharthan K, Jones WJ, Johnson JA. A priority queuing model to reduce waiting times in emergency care. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 1996;9(5):10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Gross D, Harris CM. Fundamentals of queuing theory. New York: Wiley; 1985. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.