Abstract

Cat scratch disease is often a benign infection caused by Bartonella henselae, which is transmitted from scratches or bites from kittens. Presentations can vary from localized lymphadenopathy to neurologic manifestations. We present a case of a 22-year-old man with a 3-week history of an enlarged inguinal lymph node who presented with status epilepticus.

Keywords: Bartonella encephalitis, Bartonella henselae, localized lymphadenopathy

Cat scratch disease, a self-limiting infection caused by Bartonella henselae, is transmitted when infected kittens bite or scratch humans.1–6 The overall incidence of cat scratch disease is approximately 0.77 to 0.86 per 100,000 population per year.6 The disease course is typically benign, with the appearance of regional lymphadenopathy, fever, and fatigue as the most common symptoms and resolution within 2 to 8 weeks.1,2,4–9 Severe complications such as meningitis, encephalitis, and peripheral nerve involvement can occur, usually in immunocompromised patients.1 We present a case of a 22-year-old man with a 3-week history of an enlarged inguinal lymph node who presented in status epilepticus from B. henselae encephalitis.

CASE DESCRIPTION

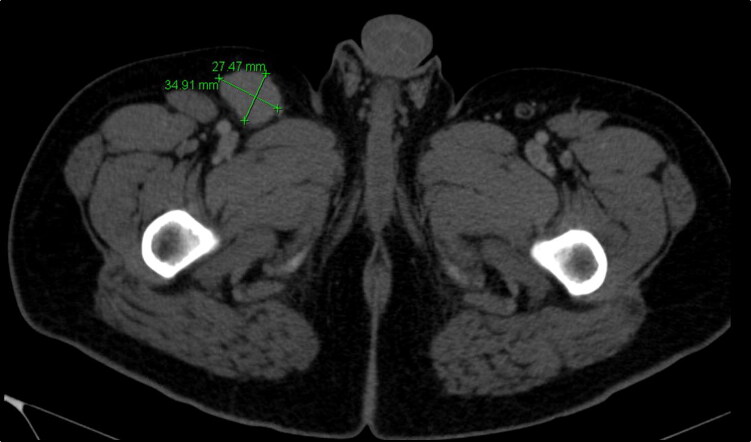

A 22-year-old man with a history of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus type 1 was seen in multiple emergency departments and clinics for progressively worsening right inguinal pain for 3 weeks. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed an enlarged lymph node (Figure 1), which was subsequently biopsied and showed necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis.

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis showing a right inguinal lymph node, measuring 3.5 × 2.8 cm.

He was scheduled for further testing but presented to the emergency department with clinical status epilepticus approximately 1 week after his biopsy. Due to his declining mental function (Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3), he was intubated and sedated for airway protection. The family reported high fevers up to 104°F, malaise, nausea, vomiting, and a 10- to 15-pound weight loss since the biopsy. He worked as an HVAC apprentice, had exposure to multiple pets including dogs, cats, and birds (unsure of vaccination status), and also worked as a transporter of feed to a cattle farm. He denied any recent pet bites or recent travel outside the United States. He was sexually active but denied any sexually transmitted diseases.

An electroencephalogram showed severe diffuse nonspecific cerebral dysfunction. CT of the head, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head, a transthoracic echocardiogram, and a lumbar puncture were unremarkable. An extensive workup for infectious diseases was performed. Bartonella serology was positive for both IgM and IgG antibodies, indicative of an acute infection with B. henselae. He completed a 4-week course of doxycycline and rifampin with no residual deficits from his encephalitis.

DISCUSSION

Neurologic involvement with B. henselae infection is rare (approximately 0.17% to 2%) and can include encephalopathy, encephalitis, meningitis, or peripheral nerve involvement.1–4,7,8 Progression to encephalitis usually occurs early in the course of the disease, with the predominant complaint being an unrelenting headache followed by rapid decline in mental status and coma.3,4,9 Seizure is the most common presenting symptom of cat scratch encephalopathy.7 The mechanism is essentially unknown but has been suggested to be mediated by toxin, immune, and direct bacterial invasion of the brain.2,4 Despite significant changes in mental status and function, most patients recover quickly without lasting damage.4,8,9

Diagnosis of acute infection involves detection of IgM, as culturing B. henselae is difficult and unreliable.1 High IgG titers (1:256) are strongly indicative of acute active infection.10 Lymph node biopsy typically shows granulomas with central necrosis and occasionally localized abscess.4,9 An electroencephalogram typically shows diffuse slowing and cerebral dysfunction.7,8 CT and MRI of the head are often unremarkable.8

Treatment of systemic cat scratch disease includes doxycycline, rifampin, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.3,7–10 A single episode of cat scratch disease will confer lifelong immunity for that individual.10

Our patient had a classic presentation of cat scratch disease, including an isolated lymph node, fever, and exposure to cats. However, this immunocompetent healthy young man quickly progressed to encephalitis. Interestingly, neurologic manifestations were previously believed to be a consequence of immunocompromise. However, more recent evidence suggests that even healthy individuals develop neurologic complications in a small number of cases. Our patient responded well to doxycycline and rifampin for 14 days. When he followed up in the clinic, he had no neurologic complications.

References

- 1.Nakamura C, Inaba Y, Tsukahara K, et al. A pediatric case with peripheral facial nerve palsy caused by a granulomatous lesion associated with cat scratch disease. Brain Dev. 2018;40(2):159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerpa Polar R, Orellana G, Silva Caso W, et al. Encephalitis with convulsive status in an immunocompetent pediatric patient caused by Bartonella henselae. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(6):610–613. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marienfeld CB, Dicapua DB, Sze GK, Goldstein JM. Expressive aphasia as a presentation of encephalitis with Bartonella henselae infection in an immunocompetent adult. Yale J Biol Med. 2010;83(2):67–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouch B, Coventry S. A case of fatal disseminated Bartonella henselae infection (cat-scratch disease) with encephalitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(10):1591–1594. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165(2007)131[1591:ACOFDB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marra CM. Neurologic complications of Bartonella henselae infection. Curr Opin Neurol. 1995;8(3):164–169. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerber JE, Johnson JE, Scott MA, Madhusudhan KT. Fatal meningitis and encephalitis due to Bartonella henselae bacteria. J. Forensic Sci. 2002;47(3):640–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherinet Y, Tomlinson R. Cat scratch disease presenting as acute encephalopathy. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(10):703–704. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.060616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan L, Reilly KM, Snyder HS. An unusual presentation of cat scratch encephalitis. J Emerg Med. 1995;13(6):769–772. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(95)02017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klotz SA, Ianas V, Elliott SP. Cat-scratch disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(2):152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazur-Melewska K, Mania A, Kemnitz P, Figlerowicz M, Służewski W. Cat-scratch disease: a wide spectrum of clinical pictures. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;3(3):216–220. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.44014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]