Abstract

Purpose of review

APOL1 nephropathy risk variants drive most of the excess risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) seen in African Americans, but whether the same risk variants account for excess cardiovascular risk remains unclear. This mini-review highlights the controversies in the APOL1 cardiovascular field.

Recent findings

In the past ten years, our understanding of how APOL1 risk variants contribute to renal cytotoxicity has increased. Some of the proposed mechanisms for kidney disease are biologically plausible for cells and tissues relevant to cardiovascular disease (CVD), but cardiovascular studies published since 2014 have reported conflicting results regarding APOL1 risk variant association with cardiovascular outcomes. In the past year, several studies have also contributed conflicting results from different types of study populations.

Summary

Heterogeneity in study population and study design has led to differing reports on the role of APOL1 nephropathy risk variants in CVD. Without consistently validated associations between these risk variants and CVD, mechanistic studies for APOL1’s role in cardiovascular biology lag behind.

Keywords: APOL1, cardiovascular, genetics

Introduction

Approximately a decade ago, a cluster of genes on the long arm of chromosome 22 was discovered to account for a large portion of increased risk of non-diabetic chronic kidney disease (CKD) in African Americans [1,2]. Over the ensuing ten years, APOL1, encoding Apolipoprotein L1, has been identified as the causative gene, and tests for its nephropathy risk variants have entered the clinical practice of nephrology. However, the mechanisms underlying APOL1-associated kidney disease and the implications of genetic testing on patient management remain unclear. Even less clear is how APOL1, which circulates on high-density lipoprotein-3 (HDL3), modulates cardiovascular disease (CVD) among African Americans and how therapeutics currently being engineered to treat APOL1-associated kidney disease may alter cardiovascular risk. Here we briefly summarize what is known about high-risk APOL1 genotype in CKD pathophysiology, discuss our current understanding of APOL1 in the context of CVD, and outline open questions for the field as it enters its second decade.

APOL1 in the kidney

APOL1 encodes a small, membrane-associated protein that enables the innate immune system to lyse the protozoan Trypanosoma brucei. APOL1 has multiple functional domains, including a signal peptide for secretion, pore-forming domain, and SRA-interacting domain that interacts with SRA produced by Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense [3–5]. Individuals who carry a single copy of the common G1 or G2 coding variant in the APOL1 gene have increased serum anti-trypanosome activity and thus are less susceptible to African sleeping sickness. However, those who carry two copies of these variants (G1/G1, G2/G2, or G1/G2), i.e., the high-risk APOL1 genotype, are at significantly elevated risk of developing kidney disease [6,7]. In case-control studies, individuals with two risk alleles are at a tenfold increased risk of hypertension-associated CKD. The odds ratios for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) are even higher at 17 and 29, respectively [8].

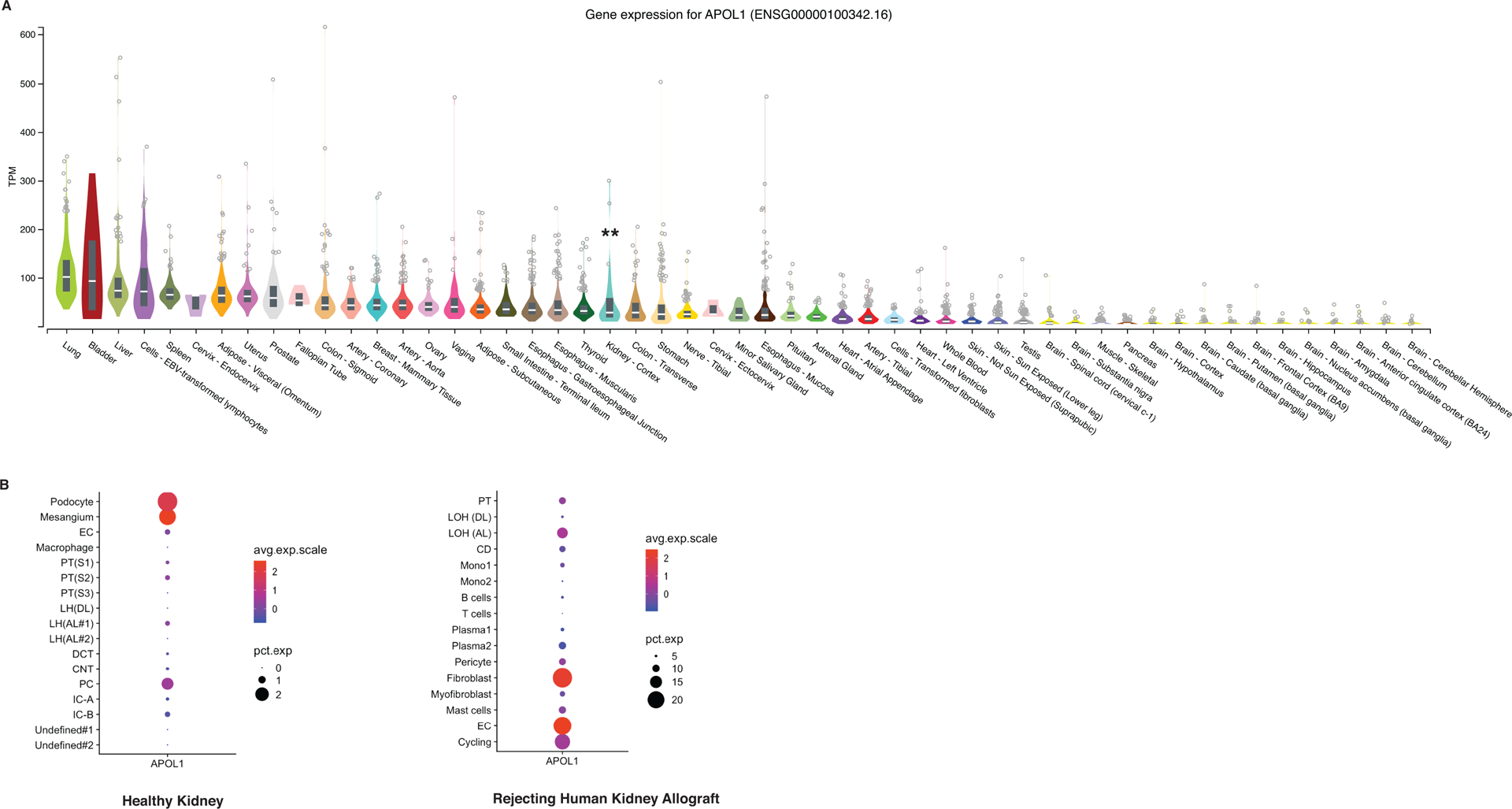

Despite strong genetic association with CKD, the mechanisms by which APOL1 induces kidney injury remain an area of active investigation with unresolved controversies potentially relevant to mechanisms of APOL1-mediated disease in other organ systems. Current mainstream hypotheses have been carefully outlined in prior reviews by Beckerman and Susztak, and by Kruzel-Davila and Skorecki [9,10]. Based on previously published reports, hypotheses for APOL1-mediated renal pathophysiology include impaired podocyte autophagy [11,12], activation of focal adhesion signaling in the podocyte in complex with suPAR [13], impaired mitochondrial metabolism [14], and depletion of intracellular potassium and signaling via stress-activated protein kinases[15]. However, several major questions remain and may be applicable in the context of CVD, discussed below. First, why does only a subset of individuals with the high-risk APOL1 genotype develop CKD? Investigators allude to a “second hit” as being necessary to induce APOL1-associated kidney disease [9,10]; would the same second hit be required for APOL1-mediated cardiovascular traits to develop? This leads to the next question of which genetic and environmental factors contribute to CKD risk. Prior genetic analyses reported conflicting results in terms of interacting genomic loci and variants [16–18], although these were performed prior to the recent identification of approximately 300 million base pairs present in African ancestry genomes but missing from the most current human reference genome build [19]. Furthermore, we have not yet determined which environmental factors contribute to disease risk. Finally, is APOL1-associated kidney disease exclusively a cell-autonomous phenomenon in podocytes? The APOL1 gene is expressed in multiple tissues, as seen in publicly available GTEx bulk RNA-sequencing data [20] (Figure 1A). It is also expressed in multiple cell types within the kidney, as demonstrated by recently published single cell RNA-sequencing data generated from human kidney biopsy samples [21,22] (Figure 1B). Although these dot plots do not represent direct statistically tested comparisons of gene expression across samples, they do suggest the that APOL1 expression may shift in a cell-specific manner, with prominent endothelial expression under injury conditions. Potential endothelial involvement in systemic APOL1-mediated cell and tissue injury may need to be considered in future studies in the kidney and other organs.

Figure 1.

APOL1 mRNA expression across tissue and cell type. A) Normalized APOL1 expression by RNA sequencing of different human tissues. **Denotes kidney expression. Adapted from gtexportal.org. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. The data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from: the GTEx Portal on 01/15/19 B) Single-cell RNA sequencing dot plots representing relative APOL1 expression in different cell types of the kidney, adapted from online database curated at humphreyslab.com., originally from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29980650. Abbreviations: EC endothelial cell PC principal cell PT proximal tubule LH or LOH Loop of Henle DCT distal convoluted tubule IC intercalated cell CD collecting duct Mono monocytes.

APOL1 beyond the kidney: causality in cardiovascular risk?

Identifying and understanding the genetic determinants of CVD have been a prioritized area of investigation for the past decade [23–25]. Because African Americans are at increased risk of developing CVD [26], multiple groups have leveraged pre-existing genetic cohorts to evaluate whether APOL1 nephropathy risk variants contribute to this excess cardiovascular risk. The initial observational study on APOL1 and cardiovascular outcomes included participants form the Jackson Heart Study (JHS) and Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and identified a twofold increased risk of CVD, defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, and surgical and endovascular interventions [27]. However, subsequent conflicting studies differ due to heterogeneity in cohort design, demographics, comorbidities of the enrolled participants, and composite outcomes. In Table 1, we provide a summary of these studies and their key findings. Examining key differences among conflicting studies may suggest strategies for moving forward in interrogating the question of APOL1’s potential link to CVD.

Table 1.

Studies examining the association between high-risk APOL1 genotype and cardiovascular disease (CVD)

| Study | Database Used | Number of participants with high-risk APOL1 genotype | Association between high-risk APOL1 genotype and composite CVD outcome? | Significant difference in age between low and high-risk APOL1 genotypes? | Participants with diabetes mellitus included? | Participants with moderate to advanced CKD included? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ito et al. Circ Res, 2014 27 | JHS, WHI | 381 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Langefield et al. Kidney Int, 2015 28 | SPRINT | 361 | No | Yes: high-risk younger, P = 0.0325 | No | Yes: proteinuria > 1 g per day and eGFR < 20 mL/min excluded |

| Freedman et al. Kidney Int, 2015 29 | AA-DHS | 91 | No: negative association with subclinical atherosclerosis | No | Yes | Yes: mean eGFR in high-risk group 85.8 mL/min and not statistically different from low-risk group |

| Mukamal et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2016 30 | CHS | 91 | Yes | No: All participants > 65 years old | Yes | Yes |

| Grams et al. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016 31 | ARIC | 470 | No | No | Yes | Yes: mean baseline eGFR in high risk group 110.4 mL/min |

| Chen et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2017 32 | AASK | 160 | No: except for in additive genetic model HR per risk allele 1.74, P = 0.04 | Yes: high-risk younger, P < 0.01 | No | Yes |

| Chen et al. J Am Heart Assoc, 2017 33 | MESA | 213 | No: except for higher risk of incident heart failure HR 1.84 (CI 1.02–3.32) | No | Yes | Yes |

| Blazer et al. PLoS One, 2017 34 | New York University’s SLE cohort | 15 | Yes: atherosclerotic disease only, no signal for heart failure | No | Yes | Yes |

| Wang H et al. Cardiorenal Med, 2017 35 | CATHGEN | 231 | No | Yes: high-risk younger, P = 0.01 | Yes | Yes |

| Chen et al. Kidney Int, 2017 36 | CARDIA | 176 | No: hypertension as outcome | Yes: high-risk younger, P = 0.01 | Yes | Yes (not excluded) |

| Gutiérrez et al. Kidney Int, 2018 37 | CARDIA | 159 | No: subclinical atherosclerosis and LVH as outcomes | Yes: high-risk younger, P = 0.02 | Yes | Yes (not excluded) |

| Gutiérrez et al. Circ Genom Precis Med, 2018 38 | REGARDS | 1346 | Yes: driven by ischemic stroke | Yes: high-risk younger, P = 0.02 | Yes | Yes |

| Franceschini et al. JAMA Cardiol, 2018 39 | WHI | 1370 | No: reported increased risk of HFpEF hospitalization | No | Yes | Yes |

| Hughson et al. KI Reports, 2018 40 | University of Mississippi | 3 | Yes: more CVD on autopsy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Abbreviations: JHS Jackson Heart Study, WHI Women’s Health Initiative, SPRINT Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial, AA-DHS African American-Diabetes Heart Study, CHS Cardiovascular Health Study, ARIC Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, AASK African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension, HR hazard ratio, MESA Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, CI confidence interval, CATHGEN Catheterization Genetics, CARDIA Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study, LVH left ventricular hypertrophy, REGARDS Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke, HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

Sample size

Although many cardiovascular cohorts tend to have large numbers of participants, they have significantly fewer African-ancestry individuals enrolled compared to European-ancestry individuals. Among the African-ancestry participants, even fewer have the high-risk APOL1 genotype, so some of these studies may not be adequately powered to detect a causal association between APOL1 risk variants and CVD. For example, the negative results from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) study, which recruited higher numbers of participants with two APOL1 risk alleles, had 80% power to detect an odds ratio (OR) of 1.53, assuming the appropriate recessive model [28]. This OR threshold is higher than some of the significant ORs ranging from 1.28 to 1.92 for the association between causal LPA variants and coronary heart disease [41], raising the possibility that a significant association exists between APOL1 and CVD, but at a more modest OR.

Defining the composite cardiovascular outcome

Out of the 14 studies listed in Table 1, five reported a positive association between high-risk APOL1 genotype and CVD. However, each study defined the cardiovascular composite outcome differently, and these differences in composite outcome may account for some of the conflicting conclusions drawn by investigators. Some studies included stroke and heart failure as part of the composite outcome, while others did not. Some measured subclinical atherosclerosis, while others focused on myocardial infarction. Some measured incident disease while others focused on prevalent disease. Uniformity in study design and measured outcomes across future cohort studies and trial groups may provide improved clarity on whether APOL1 nephropathy risk variants associate negatively with cardiovascular health.

Sweetening the inclusion criteria: participants with diabetes

Although APOL1-associated kidney disease has been described primarily in patients without diabetes, the directionality of APOL1’s effect on CVD in the setting of diabetes conflicts between studies [27, 29, 35]. For example, two large studies, SPRINT and AASK [28,32], did not find an association between high-risk APOL1 genotype and CVD, but they also did not include participants with diabetes. Ito et al. did include diabetic patients from JHS and WHI in their positive study [27]. However, Freedman et al. found that in the African American-Diabetes Heart Study (AA-DHS), APOL1 risk variants associated with lower levels of subclinical atherosclerosis and decreased all-cause mortality [29]. Diabetes is a well-known strong risk factor for CVD [42], so these different results may seem surprising. However, the AA-DHS cohort consisted of participants with very mild or no renal disease; the nature of the interaction between diabetes and CKD in the setting of APOL1 cardiovascular biology still remains unclear.

Heart the kidneys

SPRINT and population cohorts such as Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) had high mean estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) across the board, even among participants with two APOL1 risk alleles. Without much CKD represented in these studies, there may be some selection bias. When the investigators of the REGARDS study attempted to address this by stratifying their analyses by CKD status, they did not find a positive association between high-risk APOL1 genotype and CVD in individuals with CKD [38], although this could be due to some degree of survivor bias, which will be discussed below. Also worth considering is whether albuminuria is a covariate for which APOL1 genetic CVD analyses should be adjusted using standard regression. APOL1-associated kidney disease may increase the risk for CVD not only through traditional CKD-mediated pathways (e.g., hypertension and vascular calcification) but potentially through APOL1-specific pathways acting in multiple cell types and tissues (Figure 1A). If APOL1 nephropathy risk variants are pleiotropic (causal for multiple traits), regressing out albuminuria could introduce severe bias and mask a significant causal CVD relationship [43,44]. Indeed, albuminuria has recently been identified as a causal risk factor for hypertension through a large-scale Mendelian randomization study of novel albuminuria genomic loci [45]. In a more focused population albuminuria may be found to be causal in APOL1-mediated cardiovascular pathophysiology. One example of how Mendelian randomization deconvoluted a complex “cardio-renal” causal relationship is a recent Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study interrogating the relationship between lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and CVD in the setting of CKD [46]. Although Lp(a) was previously established as a causal risk factor for coronary heart disease in individuals carrying risk alleles at the LPA locus [41], Lp(a) is also elevated in the setting of CKD due to decreased clearance. Through Mendelian randomization, investigators were able to establish that genetically elevated Lp(a) independently associates with increased incidence of myocardial infarction and mortality in the CKD population. Combining CRIC with other CKD cohorts to increase power, a similar analysis with albuminuria as an instrumental variable may be informative for APOL1’s role in cardiovascular health.

Survivor bias: age is not just a number

In half of the 14 studies listed in Table 1, the high-risk APOL1 genotype group was significantly younger than their low-risk and the European-ancestry counterparts. Most of the studies with age differences had negative results in the APOL1 CVD context, raising the question of whether high-risk APOL1 genotype individuals died of cardiovascular causes before potential study recruitment and thus introduced survivor bias into negative studies. Interestingly, Hughson et al. explored this in a small autopsy cohort of younger adults and found a significant association between younger age and cardiovascular death among individuals with the high-risk APOL1 genotype [40].

Quantifying and analyzing the role of percent African ancestry

One major limitation of multiple large cohorts is the use of self-reported race and the absence of quantified percent African ancestry data. Modifiers of APOL1 risk variant toxicity may directly correlate with markers of recent African ancestry, and this was most recently demonstrated by a study of the UBD locus and APOL1-associated kidney disease [47]. We may also be under-recognizing the effect of APOL1 risk variants both in CKD and CVD by not incorporating participants with Caribbean, Central American, and South American background who may not always self-identify as black but by genetics do have high African ancestry percentage and high-risk APOL1 genotype [48].

Getting to the heart of mechanism via lipids

While the jury is still out on whether APOL1 nephropathy risk variants are causal in CVD, the rationale for studying APOL1 in a cardiovascular context has been rooted in biological plausibility. First, APOL1 circulates bound to HDL3, a subfraction of HDL that has been inversely correlated with myocardial infarction among populations of mostly European-ancestry individuals [49–51]. While HDL3 circulates in higher concentrations in African-ancestry compared to European-ancestry individuals [52], individuals with at least one APOL1 risk allele also have higher levels of total HDL and small HDL compared to those without any risk alleles in one study [53]. Interestingly, a DNA variant at the HPR locus associates with circulating APOL1 levels [54], which is congruent with other data showing that APOL1 complexes with HPR in HDL3 [55]. However, whether plasma APOL1 levels drive CVD remains unclear as they do not associate with APOL1-associated kidney disease [54]. Because dysfunctional HDL rather than total HDL-C levels is increasingly gaining traction in CVD pathophysiology [56], how risk-variant APOL1 alters HDL subfractions and lipid biology may inform its role in atherosclerosis.

Getting to the heart of mechanism via vasculature

APOL1 is expressed in cells relevant to atherosclerosis, including endothelial cells [57–58], vascular smooth muscle cells [59], and macrophages [60–61]. Whether APOL1 in vascular and immune cells causes atherosclerosis has not been reported, but the potential role of risk-variant APOL1 in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [62] may be a promising avenue of investigation given the established role of ER stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [63–64]. Because APOL1 risk variants do not associate with longitudinal blood pressure [36], their contribution to the hypertension driving putative CVD risk remains unclear. However, fetal high-risk APOL1 genotype has been linked to maternal preeclampsia (established CVD risk factor) and hypothesized to be due to placental dysfunction [65]. This finding is consistent with a published transgenic APOL1 mouse model, which did not exhibit significant podocyte loss but did have more preeclampsia events [66], providing some evidence for vascular APOL1’s role in CVD.

New insights needed from prospective studies

More prospective data on APOL1 genotype and outcomes are needed to address previously unmeasured confounders. The APOL1 Long Term Kidney Transplantation Outcomes Network (APOLLO) study will follow kidney donors and recipients who have been genotyped, allowing for structured follow-up over time [67]. This information will be of significant value as providers counsel organ donors and recipients on their renal and cardiovascular risks. GENE-FORECAST, sponsored by the National Human Genome Resource Institute, aims to identify novel predictors of cardiovascular risk in African Americans, including the role of degree of genetic African ancestry in CVD and the interplay between genetic variation and the environmental “exposome” [68]. As part of the study, investigators will perform a focused and deep genotype-to-phenotype analysis of patients with high-risk APOL1 alleles that will likely, if adequately powered, resolve some of the conflicting cardiovascular data in the APOL1 field.

Conclusion

The APOL1 story has been ten years in the making and still evolving, with questions remaining not only regarding the mechanisms by which APOL1 risk variants drive CKD, but also whether these same variants are truly causal in CVD. Additional large prospective genetic studies are needed to validate whether the high-risk APOL1 genotype associates with specific types of CVD, and mechanistic studies are also needed to elucidate APOL1’s role in cardiovascular pathophysiology.

Key Points.

Disease modifiers that drive APOL1-associated kidney disease have not been completely elucidated, and even less is known about APOL1’s role in cardiovascular pathophysiology.

Human genetic studies interrogating the association between high-risk APOL1 genotype and different cardiovascular outcomes have been conflicting due to study design differences.

More prospective clinical genetic studies and mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the role of APOL1 risk variants, if any, in the pathogenesis of CVD.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. James Brian Byrd for his discussion on this topic.

Financial support and sponsorship

JL is supported by NIH K08 HL135348.

Funding source:

Dr. Lin is supported by K08 HL135348 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, et al. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet 2008; 40:1185–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, et al. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet 2008; 40:1175–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Morga D, Vanhollebeke B, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, et al. Apolipoprotein L-I promotes trypanosome lysis by forming pores in lysosomal membranes. Science 2005; 309:469–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanhamme L, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Poelvoorde P, et al. Apolipoprotein L-I is the trypanosome lytic factor of human serum. Nature 2003; 422:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xong HV, Vanhamme L, Chamekh M, et al. A VSG expression site-associated gene confers resistance to human serum in Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Cell 1998; 95: 839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 2010; 329:841–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R, et al. Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet 2010; 128:345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22:2129–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckerman P, Susztak K. APOL1: The Balance Imposed by Infection, Selection, and Kidney Disease. Trends Mol Med 2018; 8:682–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruzel-Davila E, Skorecki K. Dilemmas and challenges in apolipoprotein L1 nephropathy research. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2019; 28:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckerman P, Bi-Karchin J, Park AS, et al. Transgenic expression of human APOL1 risk variants in podocytes induces kidney disease in mice. Nat Med 2017; 23:429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruzel-Davila E, Shemer R, Ofir A, et al. APOL1-Mediated Cell Injury Involves Disruption of Conserved Trafficking Processes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28:1117–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayek SS, Koh KH, Grams ME, et al. A tripartite complex of suPAR, APOL1 risk variants and alphavbeta3 integrin on podocytes mediates chronic kidney disease. Nat Med 2017; 23:945–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma L, Chou JW, Snipes JA, et al. APOL1 Renal-Risk Variants Induce Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28:1093–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olabisi OA, Zhang JY, VerPlank L, et al. APOL1 kidney disease risk variants cause cytotoxicity by depleting cellular potassium and inducing stress-activated protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2016; 113:830–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langefield CD, Comeau ME, Ng MCY, et al. Genome-wide association studies suggest that APOL1-environment interactions more likely trigger kidney disease in African Americans with nondiabetic nephropathy than strong APOL1-second gene interactions. Kidney Int 2018; 94:599–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *The authors executed a modestly-sized genome-wide association study for ESRD and non-ESRD cases stratified by APOL1 risk genotype and for APOL1-SNP interactions. Several loci are suggestive of an interaction with APOL1 but did not reach genome-wide significance.

- 17.Divers J, Palmer ND, Lu L, et al. Gene-gene interactions in APOL1-associated nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29:588–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodonyi-Kovacs G, Ma JZ, Chang J, et al. Combined effects of GSTM1 null allele and APOL1 renal risk alleles in CKD progression in the African American study of kidney disease and hypertension trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27:3140–3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman RM, Forman J, Antonescu V, et al. Assembly of a pan-genome from deep sequencing of 910 humans of African descent. Nat Genet 2019; 51: 30–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *This article reports that the latest reference human genome build is missing > 10% of the African genome and suggests that the standard reference genome may not be adequate for human genetics studies analyzing variants in African-ancestry participants.

- 20.The GTEx Consortium. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature 2017; 550:204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu H, Uchimura K, Donnelly EL, et al. Comparative Analysis and Refinement of Human PSC-Derived Kidney Organoid Differentiation with Single-Cell Transcriptomics . Cell Stem Cell 2018; 23:869–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu H, Malone AF, Donnelly EL, et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomics of a Human Kidney Allograft Biopsy Specimen Defines a Diverse Inflammatory Response. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 29:2069–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schunkert H, König IR, Kathiresan S, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet 2011; 43:333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Harst P, van Setten J, Verweij N, et al. 52 genetic loci influencing myocardial mass. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 13:1435–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu DJ, Peloso GM, Yu H, et al. Exome-wide association study of plasma lipids in > 300,000 individuals. Nat Genet 2017; 12:1758–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Amin MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a pooled analysis of community-based studies. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15:1307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ito K, Bick AG, Flannick J, et al. Increased burden of cardiovascular disease in carriers of APOL1 genetic variants. Circ Res 2014; 114:845–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langefield CD, Divers J, Pajewski HM, et al. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with prevalent kidney but not prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial. Kidney Int 2015; 87:169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Lu L, et al. APOL1 associations with nephropathy, atherosclerosis, and all-cause mortality in African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 2015; 87:176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukamal KJ, Tremaglio J, Friedman DJ, et al. APOL1 Genotype, Kidney and Cardiovascular Disease, and Death in Older Adults. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016; 36:392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grams ME, Rebholz CM, Chen Y, et al. Race, APOL1 Risk, and eGFR Decline in the General Population. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27:2842–2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen TK, Appel LJ, Grams ME, et al. APOL1 Risk Variants and Cardiovascular Disease: Results from the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017; 37:1765–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen TK, Katz R, Estrella MM, et al. Association Between APOL1 Genotypes and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in MESA (Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6:e007199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blazer A, Wang B, Simpson D, et al. Apolipoprotein L1 risk variants associate with prevalent atherosclerotic disease in African American systemic lupus erythematosus patients. PLoS One 2017; 12(8): e0182483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Pun PH, Kwee L, et al. Apolipoprotein L1 Genetic Variants Are Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease but Not with Cardiovascular Disease in a Population Referred for Cardiac Catheterization. Cardiorenal Med 2017; 7:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen TK, Estrella MM, Vittinghoff E, et al. APOL1 genetic variants are not associated with longitudinal blood pressure in young black adults. Kidney Int 2017; 92:964–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutiérrez OM, Limou S, Lin F, et al. APOL1 nephropathy risk variants do not associate with subclinical atherosclerosis or left ventricular mass in middle-aged black adults. Kidney Int 2018; 93:727–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *The article evaluates in the longitudinal CARDIA cohort whether APOL1 risk variants associate with markers of early CVD.

- 38.Gutiérrez OM, Irvin MR, Chaudhary NS, et al. APOL1 Nephropathy Risk Variants and Incident Cardiovascular Disease Events in Community-Dwelling Black Adults. Circ Genom Precis Med 2018; 11:e002098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *This study examines the association between APOL1 risk variants and CVD in one of the largest cohorts used to date.

- 39.Franceschini N, Kopp JB, Barac A, et al. Association of APOL1 With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction in Postmenopausal African American Women. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3:712–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *This study examines the association between APOL1 risk variants and CVD in a large cohort of post-menopausal women and found only an association with increased hospitalization due to HFpEF.

- 40.Hughson MD, Hoy WE, Mott SA, et al. APOL1 Risk Variants Independently Associated with Early Cardiovascular Disease Death. KI Reports 2018; 3:89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Study of autopsy data from a Mississippi cohort that established a significant association between early CVD death and APOL1 high-risk genotype.

- 41.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2518–2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 1999; 100:1134–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vansteelandt S, Goetgeluk S, Lutz S, et al. On the Adjustment for Covariates in Genetic Association Analysis: A Novel, Simple Principle to Infer Direct Causal Effects. Genet Epidemiol 2009; 33:394–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hemani G, Bowden J, Smith GD. Evaluating the potential role of pleiotropy in Mendelian randomization studies. Hum Mol Genet 2018; 28:R195–R208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haas ME, Aragam KG, Emdin CA, et al. Genetic Association of Albuminuria with Cardiometabolic Disease and Blood Pressure. Am J Hum Genet 2018; 103:461–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Mendelian randomization study on the bidirectional causality between albuminuria and hypertension.

- 46.Bajaj A, Damrauer SM, Anderson AH, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Death in Chronic Kidney Disease: Findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017; 37:1971–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang JY, Wang M, Tian L, et al. UBD modifies APOL1-induced kidney disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115:3446–3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Through careful genetic analyses, this study identifies UBD as a modifier of APOL1 protein expression that differs in the presence of G1 and G2 risk variants.

- 48.Nadkarni GN, Gignoux CR, Sorokin EP, et al. Worldwide Frequencies of APOL1 Renal Risk Variants. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:2571–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *The authors show that individuals of Caribbean, Central American, and South American origin carry high African ancestry percentage and APOL1 risk variants, with implications for clinical trial recruitment and data interpretation.

- 49.Salonen JT, Salonen R, Seppanen K, et al. HDL, HDL2, and HDL3 subfractions, and the risk of acute myocardial infarction: a prospective population study in eastern Finnish men. Circulation 1991; 84:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams PT, Feldman DE. Prospective study of coronary heart disease vs HDL2, HDL3, and other lipoproteins in Gofman’s Livermore Cohort. Atherosclerosis 2011; 214:196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harada K, Kikuchi R, Suzuki S, et al. Impact of high-density lipoprotein 3 cholesterol subfraction on periprocedural myocardial injury in patients who underwent elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Lipids Health Dis 2018; 17:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carr MC, Brunzell JD, Deeb SS. Ethnic differences in hepatic lipase and HDL in Japanese, black, and white Americans: role of central obesity and LIPC polymorphisms. J Lipid Res 2003; 45:466–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gutiérrez OM, Judd SE, Irvin MR, et al. APOL1 nephropathy risk variants are associated with altered high-density lipoprotein profiles in African Americans. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31:602–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kozlitina J, Zhou H, Brown PN, et al. Plasma levels of risk-variant APOL1 do not associate with renal disease in a population-based cohort. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27:3204–3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weckerle A, Snipes JA, Cheng D, et al. Characterization of circulating APOL1 protein complexes in African Americans. J Lipid Res 2016; 57:120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carnuta MG, Stancu CS, Toma L. Dysfunctional high-density lipoproteins have distinct composition, diminished anti-inflammatory potential and discriminate acute coronary syndrome from stable coronary artery disease patients. Sci Rep 2017; 7:7295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma L, Shelness GS, Snipes JA, et al. Localization of APOL1 protein and mRNA in the human kidney: nondiseased tissue, primary cells, and immortalized cell lines. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26:339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nichols B, Jog P, Lee J, et al. Innate immunity pathways regulate the nephropathy gene Apolipoprotein L1. Kidney Int 2015; 87:332–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lan X, Wen H, Saleem MA, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cells contribute to APOL1-induced podocyte injury in HIV milieu. Exp Mol Pathol 2015; 98:491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee H, Roshanravan H, Wang Y, et al. ApoL1 renal risk variants induce aberrant THP-1 monocyte differentiation and increase eicosanoid production via enhanced expression of cyclooxygenase-2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2018; 315:140–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *This study investigates the role APOL1 risk variants have in modulating macrophage phenotype and function.

- 61.Taylor HE, Khatua AK, Popik W. The innate immune factor apolipoprotein L1 restricts HIV-1 infection. J Virol 2014; 88:592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chun J, Zhang JY, Wilkins MS, et al. Recruitment of APOL1 kidney disease risk variants to lipid droplets attenuates cell toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019; epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *The authors demonstrate that risk variant APOL1 localizes to the ER instead of lipid droplets in podocytes.

- 63.Clarke MC, Figg N, Maguire JJ, et al. Apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells induces features of plaque vulnerability in atherosclerosis. Nature Medicine 2006; 12:1075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thorp E, Li G, Seimon TA, et al. Reduced apoptosis and plaque necrosis in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of Apoe−/− and Ldlr−/− lacking CHOP. Cell Metab 2009; 9:474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reidy KJ, Hjorten RC, Simpson CL, et al. Fetal not maternal APOL1 genotype associated with risk for preeclampsia in those with African ancestry. Am J Hum Genet 2018; 103:367–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bruggeman LA, Wu Z, Luo L, et al. APOL1-G0 or APOL1-G2 transgenic models develop preeclampsia but not kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27:3600–3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Freedman BI, Moxey-Mims M. The APOL1 long-term kidney transplantation outcomes network-APOLLO. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 13:940–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clinicaltrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US) 2014. February 5 −. Identifier NCT02055209. Genomics, Environmental Factors and Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease in African-Americans Study (GENE-FORECAST). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02055209 [Google Scholar]