Abstract

We outline the generality and requirements for cooperative N2H4 capture, N-N bond scission, and amido stabilization across a series of first-row transition metal complexes bearing a pyridine(dipyrazole) ligand. This ligand contains a pair of flexibly-tethered trialkylborane Lewis acids that enable hydrazine capture and M-NH2 stabilization. While the Lewis acids are required to bind N2H4, the identity of the metal dictates whether N-N bond scission can occur. The redox properties of the M(II) bis(amidoborane) series of complexes were investigated, and reveal that ligand-based events prevail; oxidation results in the generation of a transiently formed aminyl radical while reduction occurs at the redox-active pyridine(dipyrazole) ligand.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Investigations of discrete transition metal complexes containing nitrogenous ligands aim to evaluate structure/function relationships that may ultimately enable catalytic N2 reduction with high efficiency.1 Whereas landmark systems in the field often employed molybdenum,2–4 recent studies have shown many first row transition metals are viable for N2 reduction catalysis.5–9 When changing the metal, requirements for catalytic N2 reduction differ and often necessitates (re)tuning co-ligands, molecular geometry, and H+/e− sources.10 Ultimately, these modifications can result in a different mechanistic pathway of N2 reduction, rendering direct activity comparisons challenging. Access to a single platform capable of accommodating a common reduction intermediate among various metals may allow insight the role(s) of the metal identity to affect individual reduction steps.

Our group is working to evaluate how the precise structural, electronic, and cooperative modes in the secondary coordination sphere can be used to regulate reactivity.11–15 This work is inspired by metalloenzymes whose active sites often contain numerous secondary sphere acidic groups positioned near a substrate-binding site. For example, in FeMoco nitrogenase, amino acid residues residing near the active site are critical to enzymatic activity.16–17 Recently, we described a pyridine(dipyrazole) ligand scaffold, 2,6-bis(1-(CH2)3BBN-5-tert-butyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)pyridine (BBNPDPtBu; BBN = 9-borabicy-clo[3.3.1]nonyl), containing two positionally-flexible boron Lewis acids.18 These Lewis acids were employed as redox-robust surrogates for the hydrogen-bond donors (Brønsted acids) prevalent in biological systems. By comparing isostructural Fe and Zn complexes, (BBNPDPtBu)MCl2, we found that both species captured N2H4 in an identical manner through interactions with the appended trialkylboranes. However, two-electron homolytic N-N bond cleavage to form (BBNPDPtBu)M(NH2)2 only occurred with Fe. These data suggested that while the trialkylboranes may play a key role in substrate capture and product stabilization, the metal identity dictated whether subsequent redox transformations are possible. Subsequent studies from our group established that a ligand platform containing a single Lewis acid can similarly affect N2H4 capture and homolytic N-N bond cleavage, and that this reaction is also impacted by the identity of the ancillary ligands.19–20 Importantly, the generation of a free coordination site at the metal was a requisite for N2H4 reduction.20

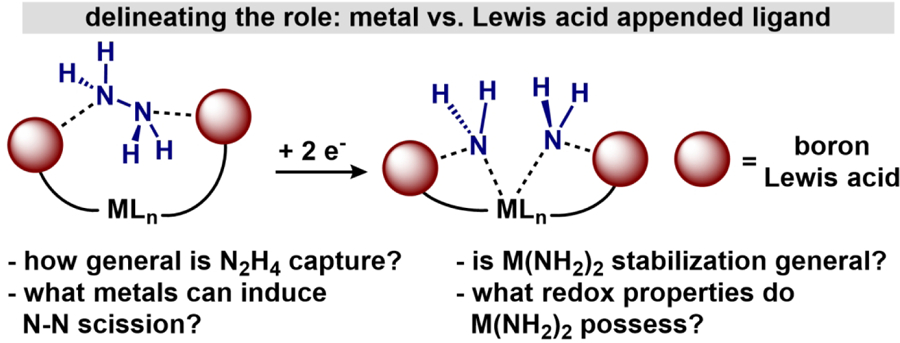

Based on our previous results, we set out to assess the following questions posed in Figure 1: 1) can the generality of N2H4 capture be extended across the first-row metals? 2) what are the requirements of a redox-active metal (access to lowvalent states) for N-N bond scission in templated complexes of the type (BBNPDPtBu)MX2(N2H4) (2-M)? 3) if N-N scission is not possible via reduction, to what extent do the boron Lewis acids provide a general approach to stabilize metal bis(amido) species, (BBNPDPtBu)M(NH2)2 (4-M)? and 4) what are the redox characteristics of borane-stabilized M(NH2)2 complexes? Herein, we report our efforts toward elucidating the roles of both the central metal and borane-appended ligand platform through the synthesis, redox transformations, and characterization of a family of first-row transition metal complexes.21

Figure 1.

Conceptual design to probe multiple aspects of N2H4 capture and reduction as well as properties of resulting bis(amido) compounds.

Results and Discussion

Boron-Dictated Substrate Capture at Divalent Metal Complexes: N-N Bond Scission Studies

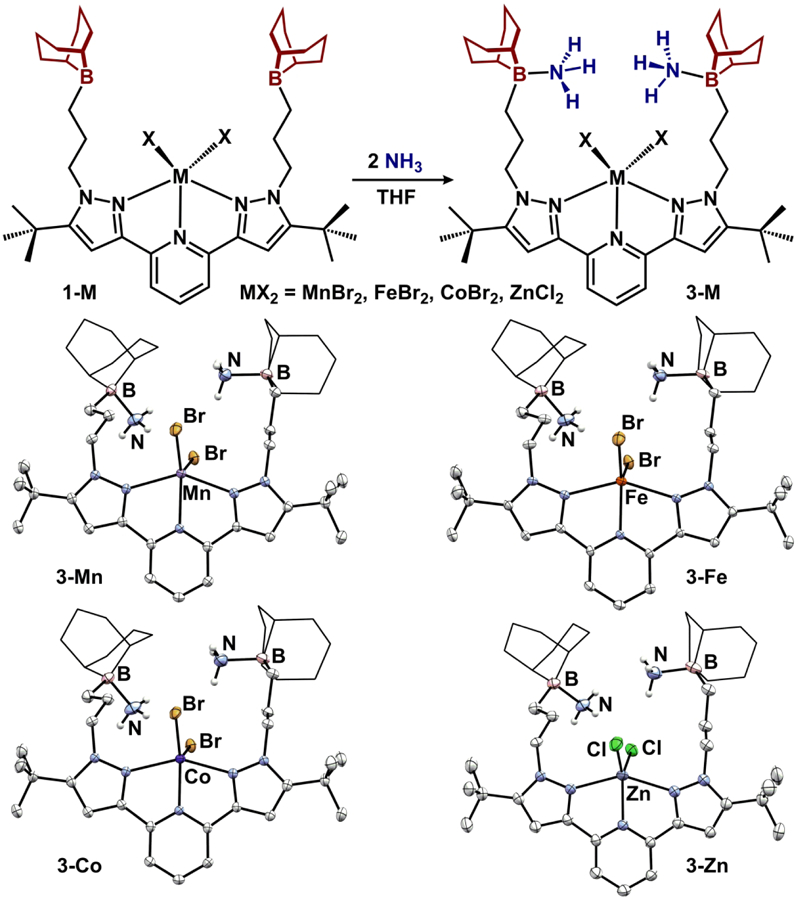

We applied our previous method for synthesizing divalent (BBNPDPtBu)MX2 (MX2 = FeBr2, ZnCl2) to both MnBr2 and CoBr2. Stirring CH2Cl2 solutions of the ligand, BBNPDPtBu, with the divalent metal precursor at room temperature overnight afforded the series of compounds (BBNPDPtBu)MX2 (1-M; M = Mn, Co, Fe, Zn) in good yields (> 72%). Complexes 1-Mn, 1-Fe, and 1-Co are high-spin divalent species with solution magnetic moments (25 °C) of 5.8(1), 4.9(1),18 and 4.2(1) μB, respectively. Compounds 1-M were assessed by voltammetry (THF, 0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6]) and all feature an irreversible oxidation event > 0.0 V (vs. Fc/Fc+) and a reduction event that is fully reversible for each species except 1-Zn. These experiments revealed 1-Co is easiest to reduce (−1.85 V vs. Fc/Fc+) and follows the trend 1-Co > 1-Fe > 1-Mn > 1-Zn.22

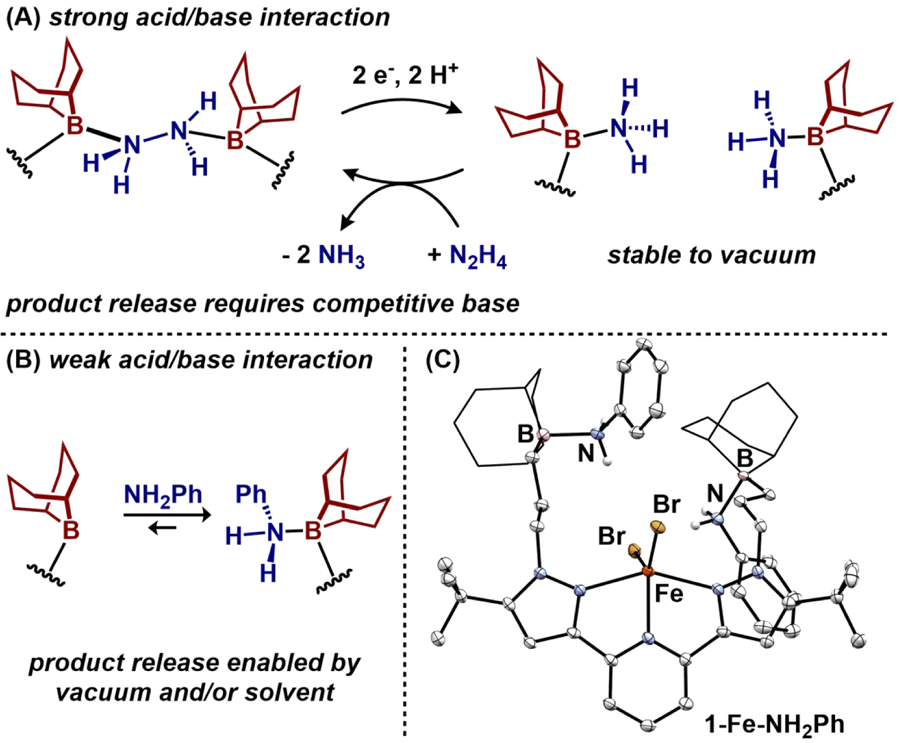

Complexes 1-M all contain non-interacting (i.e. 3-coordinate) trialkylboranes tethered in the secondary coordination sphere. Lability of a given acid/base interaction within a metal’s secondary coordination sphere is a key consideration that is necessary for any subsequent reaction that leads to turnover. Previously, we demonstrated this concept where a reaction product (NH3) was capable of being displaced by the more basic reaction substrate (N2H4) (Figure 2A).18 In that case, however, the Lewis acid/base adducts, R3B-NH3 and R3B-N2H4-BR3, were stable to both dynamic vacuum and weakly polar solvent (e.g. THF). We sought to identify a regime where B-N bond formation may be reversible, using 1-Fe as a test complex with a weaker Lewis base. In a 1H NMR titration study, addition of substoichiometric (0.5–1.5 equiv.) aniline to a THF solution of 1-Fe resulted in a gradual shifting of the paramagnetic spectrum rather than formation of a new set of resonances. These data are consistent with a dynamic regime of B-N bond formation for this Lewis base (Figure 2B). Upon adding two equivalents aniline, a new species assigned as (BBNPDPtBu)FeBr2(NH2Ph)2 (1-Fe-NH2Ph) formed. Consistent with the dynamic behavior observed in solution, the solid-state structure revealed a B-N interaction (1.710(7), 1.694(8) Å) that is elongated by ~0.05 Å compared to the ammonia-borane adduct, (BBNPDPtBu)FeCl2(NH3)2 (Figure 2C).18 This is consistent with a weaker acid/base interaction when binding aniline, compared with NH3. Repeated exposure to vacuum and precipitation with pentane gradually reformed 1-Fe, further highlighting a dynamic binding equilibrium that might be extended to product/substrate equilibration.

Figure 2.

A) Previous report demonstrating product/substrate equilibration for compounds derived from 1-Fe. B) Weaker Lewis acid/base adduct enables facile release. C) Molecular structure of 1-Fe-NH2Ph displayed with 50% probability ellipsoids. 9-BBN substituents are displayed in wireframe for clarity.

To assess the generality of N2H4 capture by the appended Lewis acids, THF solutions of complexes 1-M were exposed to a single equivalent of N2H4 (Figure 3A). Formation of (BBNPDPtBu)MX2(N2H4) (2-M) and N2H4 capture is evident by IR spectroscopy with multiple N-H absorptions spanning 3285-3095 cm−1.23 The new complexes, 2-Co and 2-Mn, remain high-spin after N2H4 capture and their molecular structures are displayed in Figure 3B. The species are isomorphous (P21/c) to their Fe counterpart and are best described as distorted square pyramidal (τ5 = 0.34 for Mn; 0.44 for Co).24 Both lone pairs of the captured N2H4 molecule are quenched by the appended Lewis acids and display B-N distances (B-Nave = 1.695 Å) similar to related systems.25 The N2H4 is 4.36 Å above the metal centers (ave. of M-to-N/Ncentroid) and participates in weak intramolecular hydrogen bonding with the adjacent bromide ligands (N-Brave = 3.50 Å).26

Figure 3.

A) Capture of N2H4 to form complexes 2-M. B) Molecular structures of 2-Mn and 2-Co displayed with 50% probability ellipsoids. 9-BBN substituents are displayed in wireframe for clarity. C) Cyclic voltammograms of 2-M (0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6], THF, 200 mV/s). D) NH4+ quantification from reduction of complexes 2-M.

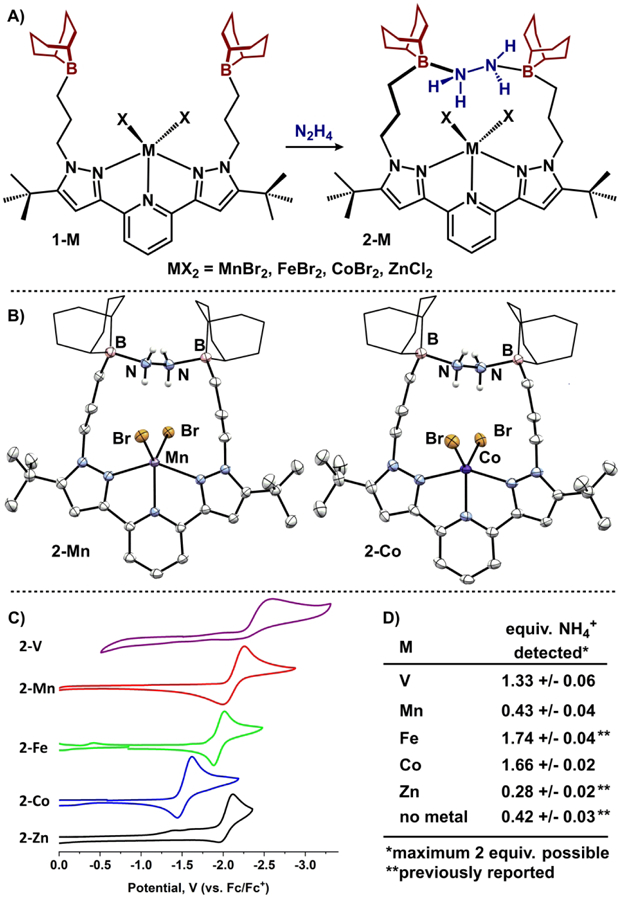

To implement a 5th metal into the series that would likely have a distinct geometry from 2-M, we targeted vanadium complexes. The formation of a divalent vanadium analogue required an alternate synthetic strategy (Figure 4). Metalation of BBNPDPtBu with VCl3 in CH2Cl2 afforded (BBNPDPtBu)VCl3 (1-V) as a light-yellow powder. 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed diagnostic paramagnetically-shifted resonances attributable to the s = 1 complex (μeff = 2.7(1) μB; 25 °C, CDCl3). The ligands are arranged in a mer-octahedral geometry and the molecular structure is displayed in Figure 4. The appended trialkyl boranes are non-interacting as indicated by the sum of the angles at boron (ΣBα = 359.8(6) and 359.8(3)°).

Figure 4.

Synthesis of vanadium compounds discussed in this manuscript. The molecular structures are displayed with 50% probability ellipsoids. 9-BBN substituents are displayed in wireframe for clarity.

1-V contains a V(II)/V(III) reduction at −1.45 V vs/ Fc/Fc+ (0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6], THF), establishing the viability of a reduced divalent vanadium complex. Through a one-pot method, (BBNPDPtBu)VCl2(N2H4)(THF) (2-V) was accessed by subsequent addition of KC8 and N2H4 to a THF solution of 1-V (Figure 4). Spectroscopically, 2-V displays strong infrared N-H absorptions (KBr) as well as visible (570, 672 nm) electronic absorptions owing to its vibrant purple color. Structural features of 2-V were evaluated through single crystal X-ray diffraction and revealed a cis-dichloride (97.180(17)°) octahedral complex where the sixth coordination site is occupied by THF. The N2H4 molecule is farther from the vanadium atom in 2-V (V-N/Ncentroid = 4.646 Å) compared its other 2-M counterparts and also displays longer B-N contacts (1.759(2) and 1.705(3) Å) likely due to geometric considerations imparted by the higher coordination number of the central atom (6 vs. 5). Upon reduction, the V-Cl distances elongate by 0.15 Å (ave.) while the V-N distances (tridentate chelate) remain unchanged. Previous studies by our lab and others have shown ligands of this type, pyridine(dipyrazole), are capable of accepting electrons.27–29 However, comparisons of intraligand C-C and C-N bond distances between 1-V and 2-V reveal no differences,30 consistent with a vanadium-based reduction event to afford a V(II) s = 3/2 complex. The isolation of octahedral 2-V in conjunction with the pentacoordinate 2-M series suggests that N2H4 capture by the pair of Lewis acidic boranes in the BBNPDPtBu ligand is general, regardless of the metal or the coordination environment at the metal.31 In other words, the appended trialkylboranes are capable N2H4 capture independent of the metal identity.

With the series of N2H4 templated species 2-M, we sought to investigate the redox requirements of the metal for N-N bond scission.32–34 Investigation of the complexes by voltammetry (0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6], THF) revealed reduction events ranging from −1.53 to −2.28 V (vs. Fc/Fc+) with 2-Co and 2-V the easiest and hardest to reduce, respectively (Figure 3C). The reductive waves of 2-Mn, 2-Fe, and 2-Co all show good reversibility at fast scan rates (>100 mV/s) while 2-V and 2-Zn are irreversible.

To assess N-N cleavage, we subjected each complex to chemical reduction with two equivalents of potassium graphite followed by acidification with excess HCl to quantify NH4+ by 1H NMR spectroscopy.35 Our previous studies showed homolytic N-N bond scission by 2-Fe produces 1.74 ± 0.04 equivalents of NH4+ by this method whereas 2-Zn exhibited low yields (0.28 ± 0.02 equiv.). Figure 3D displays the results from this study: reduction of 2-Co and 2-V produce > 1 equiv. NH4+ while 2-Mn does not produce significant quantities above the background (0.43 ± 0.04 equiv.). Whereas 2-Co (1.66 ± 0.02 equiv.) performs nearly as well as 2-Fe, 2-V (1.33 ± 0.06 equiv.) is slightly less efficient.36 These data suggest that 2-Fe and 2-Co may follow a different reduction pathway from 2-V: homolytic vs. disproportionation, respectively.37

It is instructive to compare the results of the studies entailing N2H4 capture and N-N bond scission. Each metal complex, 1-M, is capable of capturing N2H4 to form 2-M because the process is dictated solely by the ligand design, not by the identity of the metal. In contrast, not all metal complexes, 2-M, are capable of promoting the N-N bond reduction—manganese and zinc are inactive. These studies demonstrate that while the ligand framework can capture and orient a substrate for further elaboration, the identity of the metal is crucial. We hypothesized that, while the identity of the metal is important for redox transformations, the stabilization effects imparted by the trialkylboranes should remain independent of the metal. To probe this hypothesis, we sought access to an isostructural series of the theoretical N-N scission product, metal bis(amido) compounds, species which are uncommon when not protected with a Lewis acid.38–40

Borane-Stabilized Metal Bis(amido) Species

We employed a redox-neutral method for the formation of metal-amidoboranes through a stepwise ammonia capture/deprotonation protocol. Deprotonation of ammonia-borane adducts has been previously implemented for synthesizing early transition metal M-NH2BR3 complexes.41–42 Addition of a THF solution of NH3 to 1-M affords ammonia-borane complexes 3-M (Figure 5). The vanadium variant, 3-V, was synthesized via a one-pot method in analogy to 2-V and displays similar spectroscopy (Figure 4). For each, ammonia-borane formation is evident by IR spectroscopy with multiple N-H absorptions spanning 3350-3170 cm−1. For 3-Fe and 3-Co, ammonia capture is observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (CDCl3) as paramagnetically shifted resonances at −16.31 and 9.48 ppm, respectively, in their C2v symmetric spectra. Diamagnetic 3-Zn displays an 1H NMR resonance at 3.53 ppm (CDCl3) for captured NH3, and the 11B NMR spectrum contains a resonance at −5.19 ppm, consistent with a tetrahedral boron. For all complexes 3-M, the ammonia-borane adduct remains intact, even when exposed to dynamic vacuum or when dissolved in THF solution.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of ammonia-borane complexes 3-M and molecular structures displayed with 50% probability ellipsoids. 9-BBN substituents are displayed in wireframe for clarity.

The molecular structures of 3-M were determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction. All of the species in Figure 5 are isomorphous and crystallize in the same monoclinic P21/n space group. Each 5-coordinate complex is best described as distorted square pyramidal with τ5 values ranging from 0.11 to 0.24. 3-Co displays the shortest primary sphere contacts with Co-Npyridine and Co-Npyrazole(ave) distances of 2.0581(19) and 2.2395(19) Å, respectively, while 3-Mn displays the longest primary sphere contacts. The trialkyl boranes are all pyramidalized (ΣBα range 318.9(2)-328.4(6)°) and exhibit nearly equivalent B-NH3 distances (1.630(3)-1.666(4) Å) that are similar to other ammonia-trialkylborane adducts.43 The ammonia molecules participate in weak intraand intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions with the halides (N-X = 3.21-3.60 Å).26 The metrical parameters of octahedral 3-V (Figure 4) are nearly identical to 2-V, with the exception of shortened B-N distances (1.640(3) and 1.665(3) Å), likely a consequence of more degrees of freedom for the appended Lewis acid.

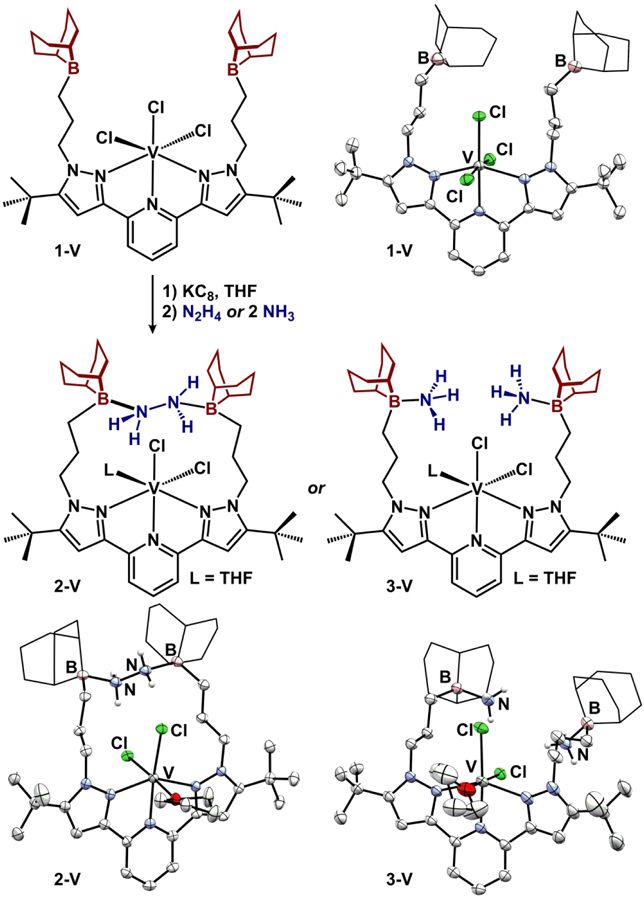

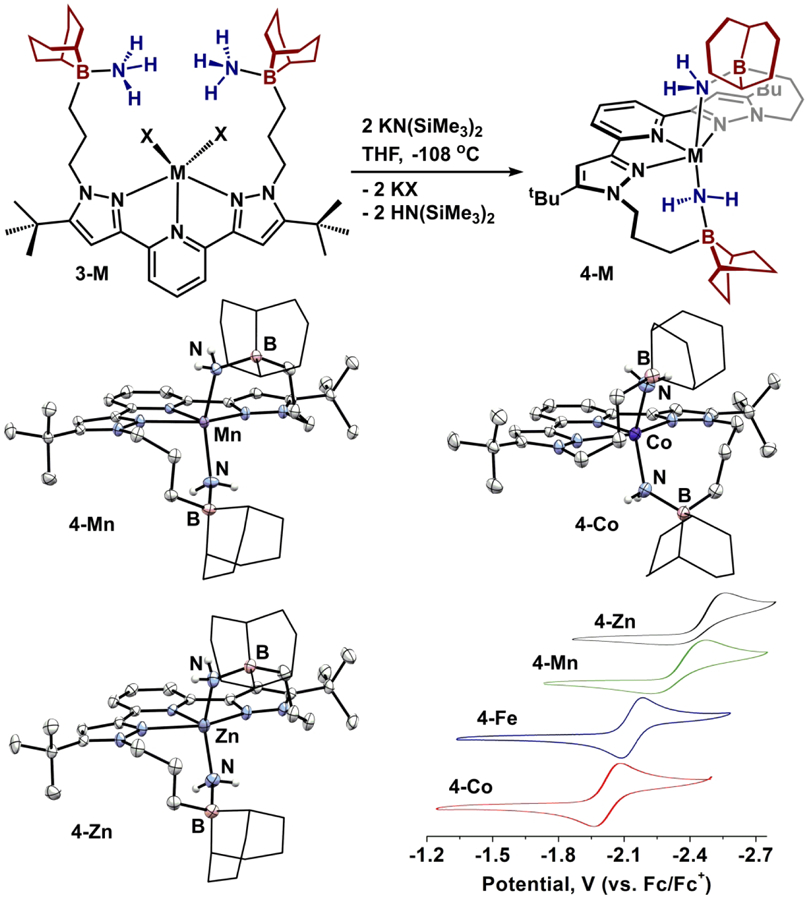

The pentacoordinate complexes 3-M were effective entry points to an isostructural bis(amido) series. Treating 3-M with 2 equiv. of a bulky base, KN(SiMe3)2, at low temperature in THF provides (BBNPDPtBu)M(NH2)2 (4-M; M = Mn, Fe, Co, Zn) in moderate yields, confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Figure 6). Solution stability (CDCl3) at room temperature reveals qualitative half-lives for 4-M on the order of ca. 24 hrs. Attempts to form a divalent vanadium bis(amido) complex using a similar protocol were unsuccessful, and may be due to an inability to form a mononuclear complex with Lewis acid-stabilized -NH2 groups that satisfies an octahedral geometry.

Figure 6.

Synthesis of amido-borane complexes 4-M and molecular structures displayed with 50% probability ellipsoids. 9-BBN substituents are displayed in wireframe for clarity. Cyclic voltammograms of 4-M: 0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6], THF, 100 mV/s.

Upon deprotonation to form 4-M, solution symmetry decreases to C2, consistent with the trialkylborane pendent groups interacting with a ligand at the metal center. Diamagnetic 4-Zn displays a pair of 1H NMR resonances (CDCl3) at −0.24 and 0.80 ppm corresponding to the inequivalent amido-NH environments and an 11B NMR resonance at −7.60 ppm consistent with pyramidalized trialkylboranes. Structural parameters for 4-Mn, 4-Co, and 4-Zn were obtained by single crystal X-ray diffraction for comparison to 4-Fe (Figure 6). Each displays a 5-coordinate metal center best described as square pyramidal (τ5 0.02–0.08) with trialkylboranes interacting cooperatively with the metal center (ΣBα(ave) = 325.8(2)°). The B-NH2 bond length remains equivalent across the series (1.619(4)-1.633(3) Å) whereas the M-NH2 distance decreases across the series 4-Mn > 4-Fe > 4-Co > 4-Zn (2.1364(17)-2.006(2) Å).

Notably, although formation of 4-Mn and 4-Zn is unattainable through reductive N-N cleavage of N2H4, their syntheses via a redox-neutral method highlights the generality of substrate (-NH2) stabilization by the appended trialkylboranes within a 5-coordinate geometry, irrespective of the metal. The only limitation appears to be instances where geometric requirements of the metal (e.g. octahedral d3 V2+) outweighs the stabilization imparted by the Lewis acids.

With a robust route to complexes 4-M established, their redox properties were assessed by cyclic voltammetry (0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6], THF; Fc/Fc+, Figure 6).44 Qualitatively, each displays similar voltammograms with an oxidation event near Fc/Fc+ and a reduction event negative of −2.0 V. In all cases, the oxidation events are irreversible with the following trend in potentials: 4-Zn > 4-Mn > 4-Co > 4-Fe (0.11 – −0.02 V).45 The reductive waves of 4-Co (−2.02 V) and 4-Fe (−2.12 V) are fully reversible while 4-Mn (−2.32 V) and 4-Zn (−2.50 V) are irreversible (Figure 6).

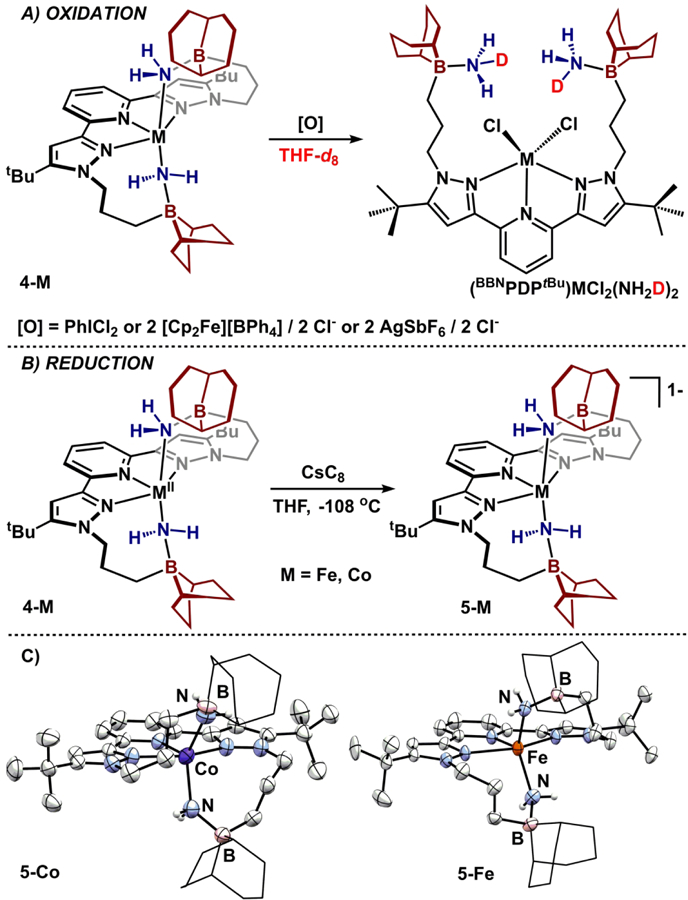

To chemically probe the oxidation events, 4-Fe was initially selected because of our prior reductive investigations with this complex, as well as established spectroscopic signatures of potential products.18 Treating 4-Fe with stoichiometric PhICl2 in THF cleanly generated a C2V symmetric species by 1H NMR spectroscopy, which was identified as previously reported (BBNPDPtBu)FeCl2(NH3)2 (Figure 7).18 We hypothesized that this product forms by oxidation, followed by H-atom abstraction. Oxidatively-induced N-N bond forming reductive elimination is rare46 and oxidation of Fe2+- and Co2+-NR2 species has previously been observed to result in rapid H-atom abstraction.47–49 To probe whether N-N bond formation was possible to reform 2-M, the oxidation reactions were carried out in a solvent with a higher C-H BDFE (DMF) and assayed spectrophotometrically to detect N2H4.50 Across the series of complexes 4-M, none of the four metals produced N2H4 from N-N coupling. To interrogate the origin of the H-atom that forms NH3 from the Fe-NH2, the reaction was repeated in THF-d8. Inspection of the 2H NMR spectrum revealed deuterium incorporation into the newly generated ammonia fragment (Figure 7A), consistent with a solvent-derived H-atom abstraction reaction. Unfortunately, variation of the solvent (o-C6H4Cl2, CH2Cl2) or oxidant ([Cp2Fe][BPh4] or AgSbF6/[Bu4N][Cl]) had no effect on the reaction, and (BBNPDPtBu)FeCl2(NH3)2 was cleanly generated in all cases.51 These data are consistent with aminyl radical extrusion occurring upon metal oxidation with subsequent H-atom abstraction occurring from solvent. This places a lower-limit BDFE of ~92 kcal/mol (from THF solvent).52 Unfortunately, oxidation attempts in solvents with higher C-H BDFE’s (e.g. C6H6, MeNO2, acetone) were marred by either low solubility of the reactant(s), instability, or chemical incompatibility (see SI).53

Figure 7.

A) Oxidation of 4-M. B) Reduction of 4-M. C) Anionic portion of molecular structures of 5-Co and 5-Fe displayed with 50% probability ellipsoids. 9-BBN substituents are displayed in wireframe for clarity.

In contrast to irreversible oxidative events observed above, compounds 4-Co and 4-Fe exhibit reversible reduction events, and thus were selected for chemical reduction studies. Treating freshly-thawed THF solutions of 4-Co or 4-Fe with CsC8 in the presence of 18-crown-6 cleanly generates dark brown complexes [Cs(18-crown-6)2][(BBNPDPtBu)M(NH2)2], 5-M (Figure 7B).54 5-Fe is modestly more stable than 5-Co (half-life of ca. 12 hr vs. 8 hr in THF at ambient temperature). Both species maintain C2 solution symmetry and a high spin electronic configuration: 5-Co is s = 1 (μeff = 3.2(1) μB, 25 °C, THF) and 5-Fe is s = 3/2 (μeff = 4.3(2) μB, 25 °C, THF). Across a temperature range of 193-298 K, the 1H NMR chemical shifts of 5-Fe obey a linear dependence on 1/T, consistent with an isolated ground state.

The molecular structures of 5-M were confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 7C). Data refinement revealed the anionic portion of 5-M to be isostructural with 4-M. Upon reduction, the M-NH2 bond lengths do not change significantly while the M-Npyridine bond length decreases ca. 0.1 Å resulting in a less idealized square pyramidal geometry (τ5: 5-Fe = 0.31; 5-Co = 0.36). The contraction of the M-Npyr distance concomitant with Npyr-Cpyr elongation are consistent with population of pyridyl-π* orbitals of the redox-active pyridine(dipyrazole) ligand.27–28, 30 Further support for this electronic structure was provided by the electronic absorption spectra of 5-Fe and 5-Co, which are qualitatively similar to [(BBNPDPtBu)FeH2]1−—a complex previously described as containing a singly reduced pyridine(dipyrazole) fragment.27 Each compound contains a set of low-(580–710 nm; 2000–8000 M−1cm−1), mid- (450–510 nm; 3200–5800 M-1cm-1), and high-energy (335-350 nm) absorbances of strong intensity (Figures S45–S47). The spectroscopic description of both 5-Fe and 5-Co are consistent with the presence of a ligand-based radical that anti-ferromagnetically couples with an unpaired metal electron to afford overall s = 3/2 (5-Fe) and s = 1 (5-Co) compounds. The LUMO description of 4-Fe accurately predicts reduction of the ligand.27

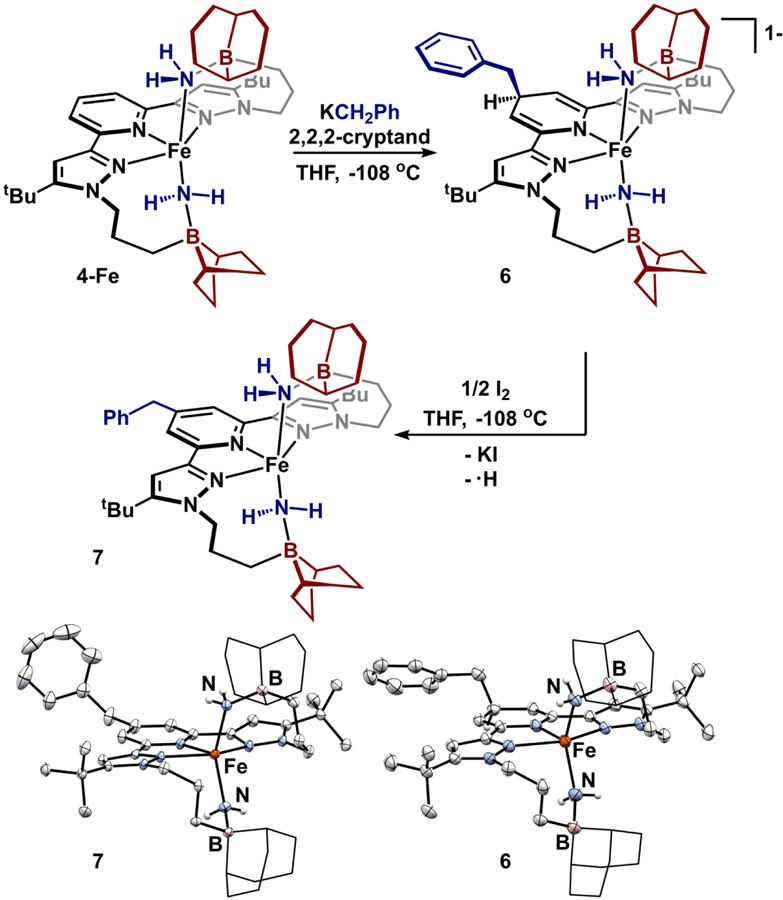

The analysis above provides insight into the thermodynamic site of nucleophilic addition to the system; however, an acidic site (e.g. -NH2) might represent another kinetically accessible site of reactivity in the presence of a Brønsted base.55 To probe reactivity with strong bases, a thawing THF solution of 4-Fe was treated with benzylpotassium (Figure 8). Analysis of the reaction product by 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed an asymmetric complex—consistent with either deprotonation or alkylation. Repeating the reaction with KCD2C6D5 and analyzing by 2H NMR spectrum revealed paramagnetically shifted C-D resonances confirming incorporation of the benzyl fragment into the complex. A single crystal X-ray diffraction experiment confirmed alkylation at the p-position of the pyridine to form [K(2,2,2-cryptand)][(benzyl-BBNPDPtBu)Fe(NH2)2] (6) (Figure 8). The coordination environment at iron remains comparable to 4-Fe (τ5 = 0.19) with Fe-NH2 distances of 2.083(4) and 2.089(4) Å. Notably, the Fe-Npyridine distance is shortened to 2.021(4) Å. Unfortunately, the pyridyl fragment was disordered, precluding further discussion of intraligand distances. Similar alkylation events have been previously observed in pyridine(diimine) systems.56–59 Notably, reactivity of the bulky strong base, LiN(iPr)2, also occurred at the p-pyridine position suggesting -NH2 deprotonation is not feasible in this system.60

Figure 8.

Alkylation of 4-Fe to produce 6 and subsequent oxidation to form 7. Molecular structures of 6 (30% probability ellipsoids; cation omitted for clarity) and 7 (50% probability ellipsoids). 9-BBN substituents are displayed in wireframe for clarity.

In 6, alkylation electronically alters the primary coordination sphere through formation of an anionic pyridine-derived fragment. To assess this influence on redox chemistry, 6 was investigated by cyclic voltammetry (0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6], THF), which revealed an irreversible oxidation at −0.49 V (vs. Fc/Fc+) that is cathodically shifted by 470 mV from 4-Fe. Chemically, the oxidative event was probed by treating a thawing THF solution of 6 with ½ equivalent of I2 (Figure 8). Following workup, solution studies revealed C2 symmetry and an s = 2 Fe(II) complex (μeff = 5.1 ± 0.1 μB, 25 °C, THF) suggesting either 1) extrusion of benzyl radical and reformation of 4-Fe or 2) H-atom loss upon oxidation and formation of (benzyl-BBNPDPtBu)Fe(NH2)2 (7). Repeating the oxidation with benzyl-d7-labeled 6 confirmed retention of the benzyl moiety, forming (benzyl-BBNPDPtBu)Fe(NH2)2 (7).61 Single crystal X-ray diffraction studies confirm 7 as a neutral species with rearomatization of the pyridine ring. Benzyl installment has minimal effects on the bonding metrics of 7 as compared to 4-Fe. Introduction of the p-benzyl substituent results in a −70 mV shift of the reductive event, compared to 4-Fe, consistent with its Hammett parameter and similar to the observed shift in related ligands.62–63 This method, alkylation/oxidation, enables a late-stage method to tune ligand field parameters of the pyridine(dipyrazole) ligand framework post-metalation. Similar strategies have been employed to modify pyridine(diimine) ligands but required demetalation of the ligand after chemical modification.64–65

Conclusions

In summary, we have disclosed a systematic study of hydrazine capture, N-N bond reduction, M-NH2 stabilization, and redox characteristics of metal bis(amidoborane) complexes. Whereas the identity of the metal center (V, Mn, Fe, Co, Zn) is the overriding factor in determining whether N-N bond scission can occur, the appended trialkylboranes regulate substrate capture and M-NH2 stabilization. These findings echo the role(s) of metal ions in biology and highlight differences between their Lewis acidic properties and substrate-specific redox transformations.

Redox investigations of the metal bis(amidoborane) complexes, (BBNPDPtBu)M(NH2)2, revealed ligand centered events: 1) chemical oxidation results in aminyl radical loss with maintenance of the M(II) oxidation state, and 2) Co and Fe readily accept an additional electron into the redox-active pyridine(dipyrazole) ligand to form high spin reduced species. Particularly attractive is the generation of aminyl radicals toward the goal of N-N coupling, and employing Lewis acids to achieve this reaction, the microscopic reverse of N-N scission, is an underexplored pathway. Studies are currently underway in developing complexes that exploit the stability afforded by the trialkylboranes toward this goal.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis:

A series of first-row transition metal complexes bearing flexibly appended trialkylboranes were synthesized and examined for hydrazine capture and N-N cleavage. While N2H4 capture is general, irrespective of the metal, N-N bond scission is metal dependent. The isolation of a series of isostructural M(II) bis(amidoborane) complexes highlights the generality of this Lewis acid approach to stabilizing highly reactive fragments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the NIGMS of the NIH under Awards 1R01GM111486-01A1 (N.K.S.) and F32GM126635 (J.J.K.). N.K.S. is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar. X-ray diffractometers were funded by the NSF under Award CHE 1625543 (M.Z.).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures and spectroscopic characterization of all species.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smil V, Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arashiba K; Miyake Y; Nishibayashi Y, A molybdenum complex bearing PNP-type pincer ligands leads to the catalytic reduction of dinitrogen into ammonia. Nat. Chem 2010, 3, 120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yandulov DV; Schrock RR, Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Single Molybdenum Center. Science 2003, 301, 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laplaza CE; Cummins CC, Dinitrogen Cleavage by a Three-Coordinate Molybdenum(III) Complex. Science 1995, 268, 861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanabe Y; Nishibayashi Y, Recent advances in nitrogen fixation upon vanadium complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev 2019, 381, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghana P; van Krüchten FD; Spaniol TP; van Leusen J; Kögerler P; Okuda J, Conversion of dinitrogen to tris(trimethylsilyl)amine catalyzed by titanium triamido-amine complexes. Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 3231–3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Castillo TJ; Thompson NB; Suess DLM; Ung G; Peters JC, Evaluating Molecular Cobalt Complexes for the Conversion of N2 to NH3. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 9256–9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prokopchuk DE; Wiedner ES; Walter ED; Popescu CV; Piro NA; Kassel WS; Bullock RM; Mock MT, Catalytic N2 Reduction to Silylamines and Thermodynamics of N2 Binding at Square Planar Fe. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9291–9301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mock MT; Chen S; O’Hagan M; Rousseau R; Dougherty WG; Kassel WS; Bullock RM, Dinitrogen Reduction by a Chromium(0) Complex Supported by a 16-Membered Phosphorus Macrocycle. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 11493–11496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Transition Metal-Dinitrogen Complexes: Preparation and Reactivity. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.: Weinheim, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl EW; Dong HT; Szymczak NK, Phenylamino derivatives of tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine: hydrogen-bonded peroxodicopper complexes. Chem. Commun 2018, 54, 892–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl EW; Kiernicki JJ; Zeller M; Szymczak NK, Hydrogen Bonds Dictate O2 Capture and Release within a Zinc Tripod. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 10075–10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanahan JP; Szymczak NK, Hydrogen Bonding to a Dinitrogen Complex at Room Temperature: Impacts on N2 Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 8550–8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hale LVA; Szymczak NK, Hydrogen Transfer Catalysis beyond the Primary Coordination Sphere. ACS Catalysis 2018, 8, 6446–6461. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahl EW; Szymczak NK, Hydrogen Bonds Dictate the Coordination Geometry of Copper: Characterization of a Square-Planar Copper(I) Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 3101–3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman BM; Lukoyanov D; Yang Z-Y; Dean DR; Seefeldt LC, Mechanism of Nitrogen Fixation by Nitrogenase: The Next Stage. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 4041–4062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sippel D; Rohde M; Netzer J; Trncik C; Gies J; Grunau K; Djurdjevic I; Decamps L; Andrade SLA; Einsle O, A bound reaction intermediate sheds light on the mechanism of nitrogenase. Science 2018, 359, 1484–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiernicki JJ; Zeller M; Szymczak NK, Hydrazine Capture and N–N Bond Cleavage at Iron Enabled by Flexible Appended Lewis Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 18194–18197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiernicki JJ; Norwine EE; Zeller M; Szymczak NK, Tetrahedral iron featuring an appended Lewis acid: distinct pathways for the reduction of hydroxylamine and hydrazine. Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 11896–11899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiernicki JJ; Zeller M; Szymczak NK, Requirements for Lewis Acid-Mediated Capture and N–N Bond Cleavage of Hydrazine at Iron. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 1147–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For an isostructural series of first-row transition metal complexes with the related proton-responsive pyridine(dipyrazole) ligand, see: Umehara K; Kuwata S; Ikariya T, Synthesis, Structures, and Reactivities of Iron, Cobalt, and Manganese Complexes Bearing a Pincer Ligand with Two Protic Pyrazole Arms. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2014, 413, 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- 22. All potentials are tabulated in Tables S2–S4.

- 23. The mono- and bis-N2H4 captured complexes display distinguishable IR spectra.

- 24.Addison AW; Rao TN; Reedijk J; van Rijn J; Verschoor GC, Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(II) compounds containing nitrogen–sulphur donor ligands; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans 1984, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen C-H; Gabbaï FP, Large-bite diboranes for the μ(1,2) complexation of hydrazine and cyanide. Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 6210–6218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steiner T, The Hydrogen Bond in the Solid State. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 48–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiernicki JJ; Shanahan JP; Zeller M; Szymczak NK, Tuning ligand field strength with pendent Lewis acids: access to high spin iron hydrides. Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 5539–5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook BJ; Chen C-H; Pink M; Lord RL; Caulton KG, Coordination and electronic characteristics of a nitrogen heterocycle pincer ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2016, 451, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labrum NS; Curtin GM; Jakubikova E; Caulton KG, The Influence of Nucleophilic and Redox Pincer Character, and Alkali Metals, on Capture of Oxygen Substrates: The Case of Chromium(II). Chem. Euro. J 2020, 10.1002/chem.202000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knijnenburg Q; Gambarotta S; Budzelaar PHM, Ligand-centred reactivity in diiminepyridine complexes. Dalton Trans 2006, 5442–5448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sterics of the X-type ligands will clearly play a role in allowing mononuclear N2H4 capture.

- 32.Umehara K; Kuwata S; Ikariya T, N–N Bond Cleavage of Hydrazines with a Multiproton-Responsive Pincer-Type Iron Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 6754–6757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakahara Y; Toda T; Kuwata S, Iron and ruthenium complexes having a pincer-type ligand with two protic amidepyrazole arms: Structures and catalytic application. Polyhedron 2018, 143, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamagishi H; Nabeya S; Ikariya T; Kuwata S, Protic Ruthenium Tris(pyrazol-3-ylmethyl)amine Complexes Featuring a Hydrogen-Bonding Network in the Second Coordination Sphere. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 11584–11586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wickramasinghe LA; Ogawa T; Schrock RR; Müller P, Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia Catalyzed by Molybdenum Diamido Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9132–9135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt EW, Hydrazine and Its Derivatives: Preparation, Properties, Applications. 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.It is plausible that both reaction pathways may be in play. For a recent example of vanadium mediated N2H4 disproportionation, see: Gu NX; Ung G; Peters JC, Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 5363–5366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zi G; Jia L; Werkema EL; Walter MD; Gottfriedsen JP; Andersen RA, Preparation and Reactions of Base-Free Bis(1,2,4-tri-tert-butylcyclopentadienyl)uranium Oxide, Cp’2UO. Organometallics 2005, 24, 4251–4264. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wraage K; Lameyer L; Stalke D; Roesky HW, Reaction of RGeBr3 (R=iPr2C6H3NSiMe3) with Ammonia To Give (RGe)2(NH2)4(NH): A Compound Containing Terminal NH2 Groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 522–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jancik V; Pineda LW; Pinkas J; Roesky HW; Neculai D; Neculai AM; Herbst-Irmer R, Preparation of Monomeric [LAl(NH2)2]—A Main-Group Metal Diamide Containing Two Terminal NH2 Groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 2142–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mountford AJ; Clegg W; Coles SJ; Harrington RW; Horton PN; Humphrey SM; Hursthouse MB; Wright JA; Lancaster SJ The Synthesis, Structure and Reactivity of B(C6F5)3-Stabilised Amide (M−NH) Complexes of the Group 4 Metals. Chem. Eur. J 2007, 13, 4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobs EA; Fuller A-M; Lancaster SJ; Wright JA, The hafnium-mediated NH activation of an amido-borane. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 5870–5872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boese R, Niederprum N, and Blaser D, in Molecules in Natural Science and Medicine: An Encomium for Linus Pauling, Eds Maksic Z and Eckert-Maksic M, Ellis Horwood Limited, England, 1991, 103. [Google Scholar]

- 44. All potentials were assessed by square wave voltammetry.

- 45. 3-Fe has stepwise oxidation events at 0.16 and −0.02 V vs. Fc/Fc+.

- 46.Diccianni JB; Hu C; Diao T, N−N Bond Forming Reductive Elimination via a Mixed-Valent Nickel(II)–Nickel(III) Intermediate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 7534–7538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Creutz SE; Peters JC, Exploring secondary-sphere interactions in Fe–NxHy complexes relevant to N2 fixation. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 2321–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sazama GT; Betley TA, Ligand-Centered Redox Activity: Redox Properties of 3d Transition Metal Ions Ligated by the Weak-Field Tris(pyrrolyl)ethane Trianion. Inorg. Chem 2010, 49, 2512–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ingleson MJ; Pink M; Fan H; Caulton KG, Redox Chemistry of the Triplet Complex (PNP)CoI. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 4262–4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Complexes 2-M and 3-M decompose immediately in DMF, therefore, spectrophotometric analysis for N2H4 was performed rather than NMR.

- 51. While the C-H BDFE of o-C6H4Cl2 is higher than THF, the C-Cl BDFE is significantly lower and following C-Cl bond homolysis will significanly weaken the adjacent C-H bond.

- 52.Luo Y-R, Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cioslowski J; Liu G; Moncrieff D, Energetics of the Homolytic C−H and C−Cl Bond Cleavages in Polychlorobenzenes: The Role of Electronic and Steric Effects. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 957–960. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reduction of 3-Fe with KC8 is also possible. Attempts at reducing 3-Co with KC8 were unsuccessful.

- 55.(a) Strong reductants are known to deprotonate acidic residues (e.g. NH2). For examples of this, see: Benito-Garagorri D; Becker E; Wiedermann J; Lackner W; Pollak M; Mereiter K; Kisala J; Kirchner K, Organometallics 2006, 25, 1900–1913; [Google Scholar]; (b) Arnold PL; Liddle ST, Organometallics 2006, 25, 1485–1491; [Google Scholar]; (c) Arnold PL; Edworthy IS; Carmichael CD; Blake AJ; Wilson C, Dalton Trans 2008, 3739–3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knijnenburg Q; Smits JMM; Budzelaar PHM, Reaction of the Diimine Pyridine Ligand with Aluminum Alkyls: An Unexpectedly Complex Reaction. Organometallics 2006, 25, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sandoval JJ; Palma P; Álvarez E; Cámpora J; Rodríguez-Delgado A, Mechanism of Alkyl Migration in Diorganomagnesium 2,6-Bis(imino)pyridine Complexes: Formation of Grignard-Type Complexes with Square-Planar Mg(II) Centers. Organometallics 2016, 35, 3197–3204. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sugiyama H; Aharonian G; Gambarotta S; Yap GPA; Budzelaar PHM, Participation of the α,α’-Diiminopyridine Ligand System in Reduction of the Metal Center during Alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 12268–12274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sandoval JJ; Palma P; Álvarez E; Rodríguez-Delgado A; Cámpora J, Dibenzyl and diallyl 2,6-bisiminopyridinezinc(ii) complexes: selective alkyl migration to the pyridine ring leads to remarkably stable dihydropyridinates. Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 6791–6793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Treating 4-Fe with LiNiPr2 resulted in para-coupling of the pyridyl fragments. Details are provided in the supporting information.

- 61. We have been unable to identify the fate of the H-atom.

- 62.Hansch C; Leo A; Taft RW, A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Darmon JM; Turner ZR; Lobkovsky E; Chirik PJ, Electronic Effects in 4-Substituted Bis(imino)pyridines and the Corresponding Reduced Iron Compounds. Organometallics 2012, 31, 2275–2285.22675236 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cámpora J; Naz AM; Palma P; Rodríguez-Delgado A; Álvarez E; Tritto I; Boggioni L, Iron and Cobalt Complexes of 4-Alkyl-2,6-diiminopyridine Ligands: Synthesis and Ethylene Polymerization Catalysis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2008, 2008, 1871–1879. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cámpora J; Pérez CM; Rodríguez-Delgado A; Naz AM; Palma P; Álvarez E, Selective Alkylation of 2,6-Diiminopyridine Ligands by Dialkylmanganese Reagents: A “One-Pot” Synthetic Methodology. Organometallics 2007, 26, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.