Abstract

The incidence of type 1 diabetes (T1D) is increasing annually, in addition to other childhood-onset autoimmune diseases. This review is inspired by recent strides in research defining the pathophysiology of autoimmunity in celiac disease, a disease that has significant genetic overlap with T1D. Population genetic studies have demonstrated an increased proportion of newly diagnosed young children with T1D also have a higher genetic risk of celiac disease, suggesting that shared environmental risk factors are driving the incidence of both diseases. The small intestine barrier forms a tightly regulated interface of the immune system with the outside world and largely controls the mucosal immune response to non-self antigens, so dictating balance between tolerance and immune response. Zonulin is the only known physiological modulator of the intercellular tight junctions, important in antigen trafficking, and therefore, is a key player in regulation of the mucosal immune response. While usually tightly controlled, when the zonulin pathway is dysregulated by changes in microbiome composition and function, antigen trafficking control is lost, leading to loss of mucosal tolerance in genetically susceptible individuals. The tenant of this hypothesis is that loss of tolerance would not occur if the zonulin-dependent intestinal barrier function is restored, thereby preventing the influence of environmental triggers in individuals genetically susceptible to autoimmunity. This review outlines the current research and a structured hypothesis on how a dysregulated small intestinal epithelial barrier, a “leaky gut”, may be important in the pathogenesis of autoimmunity in certain individuals at risk of both T1D and celiac disease.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, Zonulin, Intestinal Permeability, Celiac disease, Autoimmunity, leaky gut

Introduction:

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) is an autoimmune disease that presents most commonly in childhood with destruction of the pancreatic islet beta cells. Over time, declining production of insulin from the damaged beta cells results in dysregulation of glucose homeostasis and hyperglycemia. The long-term effect of prolonged hyperglycemia is vascular damage, resulting in a high rate of cardiovascular and renal morbidity and mortality, highest in those who develop T1D in early childhood with longer duration of disease.1 From 2001 to 2009, the prevalence of T1D in US youth increased by 21%2 and the number of youth with T1D in the United States is estimated to triple from 2010 to 2050.3 This growing prevalence is driven by a striking increasing incidence of T1D in young children which has been noted worldwide.4–6

It is well known that genetic predisposition to autoimmunity heavily influences the risk of developing T1D. However, the rising incidence of T1D over the past decade is too rapid to be attributed to an increase in genetic susceptibility. Based on reports from the USA, UK and Australia, the number of children newly diagnosed with T1D who possess the highest risk genotype (DR3-DQ2/DR4-DQ8) has decreased by 11–19% over the last 50 years, despite an increasing prevalence of T1D diagnoses.7–9 The decreased frequency of high-risk genotypes amongst those newly diagnosed with T1D, along with the striking increase in disease in the youngest age group (<age 5 years) suggests early life exposure to unknown environmental “trigger(s)” is driving the increased incidence of disease in certain genetically predisposed individuals.7

In the search for potential environmental triggers of T1D, the small intestine emerges as a key area where the mucosal immune system first interfaces with and regulates exposure to the outside environment. Tight junctions between small intestinal epithelial cells form a well-regulated barrier, allowing for selective sampling of antigens and passage of solutes while maintaining the integrity of the small intestine. This review considers evidence that zonulins, a family of proteins involved in the carefully regulated small intestinal tight junction and therefore, important in maintaining a selective barrier to environmental antigens, may play a role in the environmental risks of T1D development. In order to better understand the potential role of the zonulin pathway in development of T1D, it is important to differentiate genetic from environmental risk factors – particularly those related to the intestinal mucosal barrier. These issues are further discussed below.

Type 1 Diabetes Genetic Risk:

The majority of genetic T1D risk is tied to genes within the class II HLA region, which largely encode antigen-presenting molecules that determine adaptive immunity and the immune system’s recognition of self vs. non-self antigens. Some of the common gene polymorphisms that predispose to the development of T1D are also associated with risk of other autoimmune diseases, most commonly Hashimoto thyroiditis and celiac disease,10–12 but also systemic autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.13,14 Of the class II HLA genotypes that predispose to T1D autoimmunity, the highest risk are DR3—DQ2 and DR4—DQ8.15 A large proportion (40%) of those with T1D have one or both of these specific well-known risk genotypes, either HLA DR3-DQ2 and DR4-DQ8 heterozygous (typically referred to as HLA DR3/DR4-DQ8), or homozygous for DR4-DQ8 (referred to as HLA DR4/DR4).16 Children possessing the highest-risk HLA genotypes have a 3.7% risk of developing T1D by age 10 years17 as opposed to a 0.3% lifetime risk of developing T1D in the general population.18 Recent investigations into HLA, non-HLA genes and T1D-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), have allowed investigators to predict the risk of developing T1D more accurately, permitting the generation of more precise genetic screening tools for use in the general population.19 Despite improvements in the identification of the population at greatest risk to develop T1D, it is not yet known what specifically triggers autoimmunity in genetically predisposed individuals.

Autoimmunity and the Prediction of T1D:

Circulating autoantibodies to the pancreatic islet cells are identified prior to the onset of insulin deficiency and T1D, largely considered markers of the autoimmune attack on beta cells that ultimately leads to insulin deficiency. The most commonly-tested autoantibodies directed against target antigens identified in T1D are insulin antibody (IAA), glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody (GADA), protein tyrosine phosphatase-like antigen antibody (IA-2A or ICA-512), islet cell antibody (ICA) and zinc transporter 8 antibody (ZnT8A).20 While only a small proportion of children who develop a single T1D-specific autoantibody progress to T1D disease, this risk increases significantly if multiple autoantibodies develop. Pooled analysis of large studies show that >85% of children with multiple diabetes-specific antibodies progress to T1D over a 15 year period, although the time to diagnosis is variable.21 Young age of initial antibody positivity in genetically at-risk infants and children is a predictor of rapid progression to T1D, contributing to the rising overall incidence.22

T1D diagnosed at a young age:

In addition to young age of initial antibody positivity predicting rapid progression to clinical disease, there is evidence that islet cell dysfunction progresses more rapidly amongst this young age group.22 Young age of T1D diagnosis is associated with a lower level of endogenous insulin production at diagnosis and a steeper drop in insulin production during the first year after diagnosis, as reflected by a lower baseline C-peptide level23 and a more dramatic slope of declining C-peptide levels following a mixed-meal test, when compared with adolescents and adults.24

The youngest children with T1D have been shown to demonstrate a dramatic progression to insulinopenia, and research suggests that this patient group is expanding worldwide. In fact, the rise in incidence of T1D has been the highest amongst the youngest children (age < 5 years), a trend that has been observed since the 1990s.25 This trend does not appear to be related to a rise in prevalence of high risk HLA genes, as the opposite has been shown, with the proportion of newly diagnosed children with the highest risk HLA genotypes declining over time.7–9 In a US study evaluating for changes in HLA genotype frequencies over the last 40 years in the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium (T1DGC) cohort, a decrease in high-risk HLA genotype DR3/DR4-DQ8 was observed among all age groups but was particularly striking among ages ≤5 years old. Greater than 50% of children ≤5 years old diagnosed with T1D before 1985 possessed the high-risk genotype compared to 39% of those diagnosed between 1995–2006.26 This has also been mirrored by several other large studies showing the prevalence of the highest risk genotype (DR3/DR4-DQ8) among newly diagnosed with T1D in the youngest age groups (age <5 years) has decreased by 11–19% over time, despite an increasing prevalence of T1D diagnoses.7–9 Seen along with this decrease in the highest-risk HLA, is a rise in proportion of the intermediate-risk homozygous genotypes DR3/DR3 or DR4/DR4 and the heterozygous genotypes possessing either one copy of DR3 or DR4 (abbreviated DR3,X and DR4,X).9

There is now building evidence that children who are younger at age of T1D diagnosis have a higher risk of comorbid celiac disease, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease that is triggered by the ingestion of gluten. A population-based study on 4,322 children with T1D in Italy showed a three-fold higher rate of biopsy-proven celiac disease among those diagnosed with T1D at ages younger than 4 years as compared to those diagnosed older than age 9 years.27 The finding of this study performed in an Italian cohort was also confirmed by an international registry study (Germany/Austria, US, England/Wales, Australia) which found a greater risk of celiac disease in children diagnosed with T1D at a young age.28 Why this younger age group appears to be at a higher risk of concurrent celiac disease has yet to be established, but may be explained in part by the HLA gene trends in this special population.

Celiac Disease and its relationship to Type 1 Diabetes:

Concomitant celiac disease will ultimately develop in approximately 6% of patients with T1D,29 a much higher prevalence than in the general population, estimated at 1%.30 This shared genetic predisposition is strongly related to specific HLA genes such as DR3-DQ2 and DR4-DQ831,32 and DQ2.5/DQ833 as well as non-HLA genes and specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) which confer risk of both T1D and celiac disease.12,32–34

The HLA risk of developing celiac disease in the general population is conferred largely by presence of DQ2 and/or DQ8 alleles, either of which are considered requisite for the development of celiac disease.35 Although the risk of co-occurrence of celiac disease and T1D is increased in individuals with the highest risk HLA for T1D (HLA DR3-DQ2/DR4-DQ-8), the intermediate-risk T1D genotype HLA DR3-DQ2/DR3-DQ2 (DR3/DR3) confers the greatest risk of celiac disease in the general population.35,36 In the multinational TEDDY study (The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young), the DR3/DR3 genotype was associated with the highest risk of celiac disease autoimmunity among children with T1D, as measured by tissue transglutaminase IgA antibody level, with a dose-related effect of having more DR3 alleles on risk of celiac disease autoimmunity.37 The observed increase in prevalence of genotypes which confer a shared risk of both celiac disease and T1D (DR3/DR3) amongst the youngest children (<5 years) diagnosed with T1D,9 and the rising incidence of celiac and T1D autoimmunity amongst this age group has added fuel to the hypothesis that a shared environmental exposure is influencing the penetrance of both diseases in a population that historically had a lesser genetic risk of developing early T1D.

Careful evaluation of the similarities between T1D and celiac disease may allow us to explore further the shared pathogenesis of autoimmunity. As seen in T1D, markers of disease-specific autoimmunity are present at the time of celiac disease onset, with serum immunoglobulin A (Ig A) antibodies to tissue transglutaminase (tTG) considered a primary screening test with high sensitivity and specificity for active celiac disease.38 However, unlike T1D, the key environmental trigger for celiac disease has been identified: intestinal exposure to gliadin, a protein component of gluten. Dietary gluten exposure in those with celiac disease susceptibility triggers the appearance of inflammatory markers at the level of the gut and exposure to gluten leads to small intestinal mucosal damage, accompanied by further dysregulation of the small intestinal barrier function. The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study recently demonstrated increasing gluten consumption before the age of 5 years had a dose-related effect on increased celiac disease incidence in children at risk of T1D.39 Identification of one of the environmental triggers of celiac disease has allowed for disease-modifying therapy by restricting exposure to dietary gluten. Gliadin is currently being explored as one of the possible environmental triggers of T1D, driven forward by evidence that removal of dietary exposure to gliadin is protective against the development of autoimmunity in certain murine models of diabetes.40 While studies investigating the amount of gluten intake on the incidence of T1D have demonstrated mixed results, several suggest a potential role of timing of gluten introduction as a risk factor for the development of T1D in younger children. For instance, the TEDDY study has found increasing risk of T1D autoimmunity in infants with delayed introduction of gluten, after age 9 months.41 These findings were supported by the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) study identifying increased risk of T1D autoimmunity with both early (≤3 months) and later (>7 months) introduction of all cereals, both rice or gluten-containing, in children at high genetic risk of T1D. Recently, the Finnish Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention (DIPP) Study reported a dose-effect response of increased gluten-containing cereal intake on development of T1D autoantibodies, in children younger than age 6 years, while an effect was not seen in older children.42 In contrast, a recent DAISY study had found no effect on amount of gluten intake on T1D autoimmunity at age 1–2 years old, but did identify that early gluten introduction at age prior to 4 months presents an increased risk of T1D among infants.43 The supposed role of gliadin in the pathogenesis of T1D has been reviewed in detail by Serena G et al.44 Taken together, this early research suggests a potential dose-effect of increased gluten intake, or introduction of gluten outside of a specific time “window” (from age 4–7 months) may be environmental “triggers” of T1D in a certain subset of young children, potentially in individuals at risk of both T1D and celiac disease.

As with T1D, observed increases in celiac disease prevalence have lead researchers to question the previous paradigm that genetic predisposition and exposure to environmental trigger(s) are necessary and sufficient to initiate the autoimmune process. With regards to childhood-onset autoimmune diseases, several important infective hypotheses have been established to explain the observed spike in prevalence. The “fertile field hypothesis” is based on the concept that certain viral and microbial exposures induce a temporary innate immunological state in individuals with a predisposition to the generation of autoreactive T-lymphocytes.1 In this hypothesis, exposure to microbial infection at a time when the immune system is primed (e.g. the field is “fertile”) is proposed to cause an exaggerated inflammatory response or expansion of auto-reactive T-cells, leading to dysregulation of immune tolerance. This hypothesis is supported in part by the lack of identification of a single infection that has “triggered disease”, instead suggesting that more than one subsequent infection is needed to intensify the number and activity of auto-reactive T-cells. This hypothesis also postulates that the antigens present in the field vary according to the host’s age and ability of the immune system to respond (immature vs. mature immune system) and also appears to be modulated by how many antigens are exposed to the host mucosal immune system (via dysregulation of the intestinal barrier function).45 In contrast to the fertile field hypothesis, the “hygiene hypothesis” postulates the opposite pathogenesis, arguing that the rising incidence of many autoimmune diseases may partially be the result of lifestyle and environmental changes that have made us too “clean” for our own good. Improved hygiene and lack of exposure to various microorganisms also have been linked with a steep increase in autoimmune disorders in industrialized countries during the past 40 years.36 In addition, murine models of diabetes including non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice are more likely to develop diabetes autoimmunity when raised in a pathogen-free environment, as well as in the context of a sterile cesarean section delivery free from early life microbial exposures.46 While limited study in humans has been performed, there is some evidence from a study in the United Kingdom that increasing daycare exposure (assumed to lead to increased early infectious pathogen exposure) is protective from the development of T1D.47 In the TEDDY study, attending daycare before age 2 years was associated with a decreased T1D risk among breastfed children, with a dosage-effect, while daycare exposure in non-breastfed infants had the opposite effect, an increased T1D risk.48

In the hygiene hypothesis, early life exposure to certain milder enteric infections is felt to be key in normal immune stimulation, training and the development of tolerance during a crucial period of development in mucosal immunity. If exposed to infections following the missed crucial training period, the innate immune response may be exaggerated, or not protected by a mature gut mucosal immune system that is self-tolerant. In both the fertile field hypothesis and the hygiene hypothesis, a defective gastrointestinal tract barrier or gut dysbiosis may serve as a common “route” to autoimmunity. The absence of a stable gut microbiome may set the stage for the development of a post-infectious inflammatory state triggering expansion of auto-reactive T-cells (“fertile field”). Alternatively, in context of dysbiosis, early infections or exposures may fail to initiate innate immune tolerance in the developing intestinal mucosal immune system whereby later (postponed) exposures to intestinal infections or environmental antigens may subsequently lead to the development of autoimmunity and loss of tolerance (the “hygiene” hypothesis). In addition, the “old friends” hypothesis49 concludes that the normal microbes that call the intestine home (e.g. old friends) are crucial for the stimulation of low-grade regulatory T-cell activity that push the cytokine mileu towards more regulatory vs. inflammatory bias, discouraging the effects of proinflammatory processes. In effect, the “old friends” may lead to prevention of a “fertile field”. These three hypotheses overlap within a fourth hypothesis, now named the “perfect storm hypothesis”50,51 whereby the trio of a “leaky” or dysregulated intestinal mucosal barrier, aberrant intestinal microbiota and predisposition to an exaggerated intestinal immune response, may be responsible for this uptick in autoimmune disease and type 1 diabetes. Regardless of the hypothesis for the “triggering” event, all of these hypotheses share one common element, dysbiosis, which is now felt to play a key role in the generation of autoimmunity.

While our ability to map the intestinal microbiome has led to a greatly improved understanding of the role of the gut microbiological ecosystem in dictating the balance between tolerance and immune response leading to autoimmunity, the aforementioned hypotheses remain under scrutiny. Regardless of whether autoimmune diseases are due to too much or too little exposure to microorganisms, it is generally accepted that adaptive immunity and imbalance between Type 1 and Type 2 helper T cell (Th1 and Th2) responses are key elements of the pathogenesis of the autoimmune process. Besides genetic predisposition and exposure to environmental triggers, there appear to be several “key ingredients” in the autoimmunity recipe: the loss of intestinal barrier function, an inflammatory innate immune response to certain environmental exposures, an inappropriate adaptive immune response, and an imbalanced gut microbiome. Celiac disease and T1D are no exception to this new pathogenetic paradigm.

The Intestinal Barrier:

The single layer of intestinal epithelial cells lining the small intestine serves an important role as “gate-keeper” for the immune system. It must selectively regulate the passage of the usual milieu of dietary antigens without activation of the immune system, and manage both “friendly” symbiotic and “unfriendly” enteric microorganisms. Most dietary proteins cross the intestinal barrier via the transcellular pathway, undergoing endocytosis and passage through the intestinal epithelial cell. This allows dietary proteins to be converted into smaller peptides by lysosomal degradation, preventing immune system activation. Passive fluid and solute transport largely occur by paracellular transportation (between cells) regulated by tight junctions, the principal component of the apical cell junction domain.44 In pathological or inflammatory states, the barrier of the tight junction is dysregulated, allowing the passage of larger numbers of antigenic molecules or microbes through the paracellular pathway.49 As established by our lab’s prior mechanistic studies, abnormal function of the paracellular barrier due to poor competency of the tight junction may play a role in the pathogenesis of T1D autoimmunity (illustrated in Figure 1). In this hypothesis, diminished integrity of the intestinal barrier by excessive release of zonulin, a protein released by epithelial cells lining the small intestine, leads to excessive leakage of antigens through tight junctions. Whereby in physiologic states, the opening of the tight junctions in response to certain environmental exposures is transient and tightly regulated, in the dysregulated state, prolonged opening of the tight junctions by excessive zonulin release leads to increased antigen passage through the intestinal barrier. The increase in antigen trafficking may lead to inflammation and inappropriate activation of the innate (and adaptive) immune response, leading to break of tolerance to abnormal self-antigens and, ultimately, onset of autoimmunity or “intolerance of self” in genetically-predisposed individuals.46,47

Figure 1:

The proposed mechanism by which unregulated zonulin can lead to inappropriately increased intestinal permeability and resultant loss of immune tolerance. Intestinal permeability, together with (1) transcellular antigen sampling by enterocytes and antigen sampling by luminal dendritic cells, regulates molecular trafficking between the intestinal lumen and the submucosa, leading to either (2) tolerance or immunity to non-self antigens. (3) Gut dysbiosis and/or gliadin exposure causes (4) zonulin release from the small intestine and reversible opening of the tight junction barrier. Persistent gut dysbiosis leads to switching from controlled antigen trafficking to zonulin-dependent increased antigen trafficking secondary to (5) changes in tight junction-related gene expression. (6) This increased antigen trafficking leads to inflammation that further increases gut permeability, ultimately leading to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, T-cell activation and loss of tolerance in individuals with immunoregulatory defects. This is hypothesized to be the triggering event for onset of islet cell autoimmunity in T1D. This figure was created using Servier Medical Art templates, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License; https://smart.servier.com.

Zonulins: Mechanism of Action and Association with Inflammation:

Much of our understanding of the function of the tight junctions has been through identification of the zonulin family of proteins: the only known physiological regulators of the intestinal tight junction, with signaling mechanism shown in Figure 2.48 Zonulins are 47 kDa paracrine proteins released by several cell lines in the body55, including the epithelial cells lining the small intestine which modulate the opening of the intestinal tight junctions. Luminal zonulin release is stimulated by either exposure to gliadin the primary component of gluten, or microbiome imbalance (dysbiosis or proximal bowel colonization).57 The mechanism by which gliadin leads to zonulin release from intestinal epithelial cells is well-characterized and summarized in Figure 3. On enterocytes and monocytes, gliadin binds to the CXCR3 chemokine receptor and leads to MyD88-dependent zonulin release and subsequent increased intestinal permeability.56 For details on the full mechanism, see recent review article by Sturgeon and Fasano.58

Figure 2:

Representation of the mechanism of action of zonulin. A. During the resting state, both homophilic and heterophilic protein-protein interactions keep the tight junction (TJ) proteins in a closed and competent state, as depicted in the freeze fracture electron microscopy photograph. B. Following zonulin pathway activation: Zonulin transactivates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) through protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) (1). The protein then activates phospholipase C (2) that hydrolyzes phosphatidyl inositol (PPI) (3) to release inositol 1,4,5-tris phosphate (IP-3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) (4). Protein kinase C alpha (PKC-α) is then activated (5), either directly (via DAG) (4) or through the release of intracellular Ca2+ (via IP-3) (4a). Membrane-associated, activated PKC-α (6) catalyzes the phosphorylation of target protein(s), including zona occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) and myosin 1C, as well as the polymerization of soluble G-actin in F-actin (7). The combination of TJ protein phosphorylation and actin polymerization causes the rearrangement of the filaments of actin and leads to the subsequent displacement of proteins (including ZO-1) from the junctional complex (8). As a result, the intestinal TJ becomes looser (see freeze fracture electron microscopy). Once the zonulin signaling is over, the TJ again closes and resumes baseline steady state. Figure reprinted from Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Vol 10, Fasano A, Intestinal Permeability and Its Regulation by Zonulin: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications, Page 7, Copyright (2012), with permission from Elsevier.93

Figure 3:

Mechanism of gliadin- and bacteria-induced zonulin release and subsequent increase in intestinal permability. Gliadin or bacteria (1) cause zonulin release through binding to the CXCR3 chemokine receptor. Zonulin release is MyD88-dependent (2). Following release into the lumen of the small intestine, zonulin transactivates the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) through protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) leading to Protein kinase C alpha (PCK-α) dependent tight junction disassembly (3). Increased intestinal permeability leads to paracellular passage of non-self antigens (4) into the lamina propria where they are able to interact with the immune system. Zonulin inactivation occurs by proteolytic degradation by Trypsin IV (5). This figure was created by use of Servier Medical Art templates, which are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License; https://smart.servier.com.

In addition, bacterial colonization of the small intestine by certain enteric microorganisms (both virulent and avirulent) has been shown to trigger small intestine zonulin release.57 In fact, the discovery of zonulin can be attributed to investigations into a key pathogenic bacteria, Vibrio cholerae, that expresses Zot (zonula occludens toxin). Zot is an enterotoxin that reversibly opens the small intestinal tight junctions by binding to the zonulin receptor, creating a “leaky gut” through breakdown of the tight junction barrier, resulting in a characteristic severe, watery diarrhea. By exposing luminal small intestinal segments from multiple mammalian species to virulent and non-virulent strains of E.coli (strain 21–1 and strain 6–1) and S. typhimurium, our lab was able to elicit increased intestinal permeability, measured by transepithelial resistance, which directly correlated with increases in zonulin secretion from the luminal (but not serosal) side of the small intestinal mucosa.57 Of note, these effects were only notable in the small intestine, where zonulin receptors have been identified. When the same experiments were ran in the mammalian colon, an area shown to not express the zonulin receptor, there were no changes in intestinal permeability.57 This bacterial-triggered zonulin release has been shown in the absence of elaboration of toxins (like Zot) and also in absence of mucosal damage, suggesting that zonulin release is not exclusive to pathogenic bacterial exposure.57 Moreover, the observed increases in intestinal permeability in response to bacterial exposure are abolished by pretreatment with the zonulin receptor synthetic peptide binding inhibitor57, establishing that small intestinal zonulin release is a key step in the mechanism allowing bacteria to induce tight junctional conformational change and increases in intestinal permeability. While the mechanism of bacterial induction of the zonulin system is not completely elucidated, it is thought that zonulin release is initiated by small intestinal dysbiosis through steps similar to gliadin activation of the mechanism outlined in Figure 3. Since bacterial small intestinal colonization has been identified as a trigger of zonulin release, it has been proposed that zonulin release is a tightly-controlled physiologic mechanism which modulates the microbial colonization of the small intestine through changes in intestinal permeability.59 This foundational research continues to be a focus of the Fasano lab, and our group has recently published on a zonulin transgenic mouse model, genetically engineered to express murine zonulin, which not only responds to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis with significant increased intestinal permeability and increased morbidity and mortality,60 but also possessed a significantly altered gut microbiota composition with reduced quantity of the genus Akkermansia, which classically has positive effects towards mucosal barrier integrity. These zonulin transgenic mice were also resistant to efforts to “normalize” the microbiota via transfer of wild type microbiota.61 This recent research supports the idea that a dysregulated zonulin system could be driving intestinal dysbiosis. As of the date of this publication, the mechanism by which the bacterial colonization of the proximal intestine leads to alterations in tight junction function is not yet known but is of significant interest.

Haptoglobin Genotype and Zonulin Production:

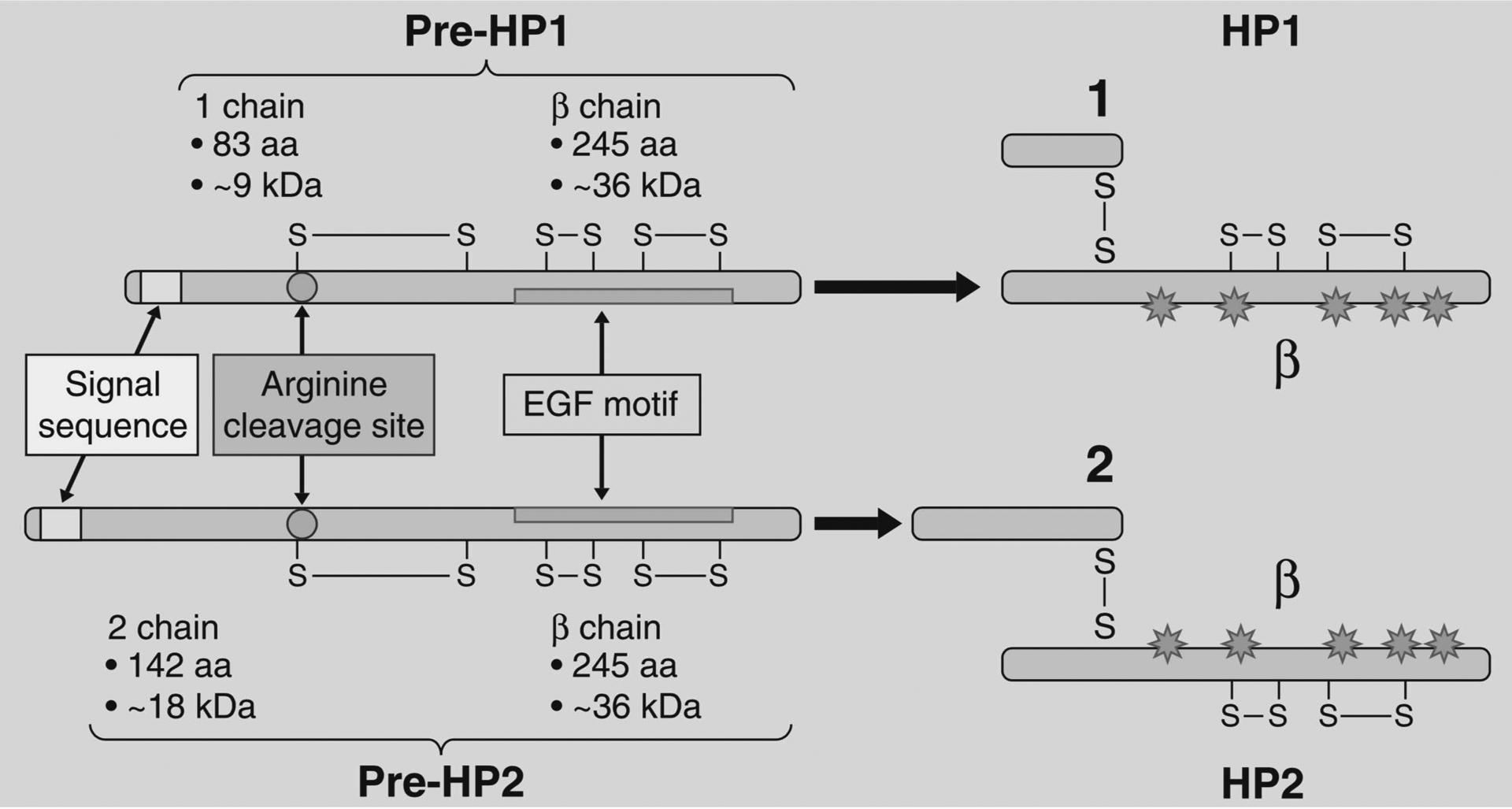

By proteomic analysis of human sera, the human zonulin family archetype was identified by our group to be pre-haptoglobin 2 (pre-HP2), the uncleaved precursor protein to one of the human variants of the haptoglobin glycoprotein.55 Mature haptoglobin is an acute-phase protein that binds to free hemoglobin to prevent oxidative damage. There are two human genetic variants of the haptoglobin (HP) gene, HP1 and HP2 which differ only in the α-chains as shown in Figure 4. Since each individual has 2 alleles for haptoglobin, there are 3 possible human genotypes (HP1–1, HP1–2, HP2–2). Those who possess the HP2 allele (HP1–2 or HP2–2) produce active zonulin (pre-HP2) whereas those with the HP1–1 genotype do not have detectable zonulin. The frequencies of each haptoglobin phenotype vary worldwide according to the population being studied.62 Estimated to be the origin of the HP2 allele about 2 million years ago, India has the highest proportion of HP2–2 homozygous individuals at 84% of the population.63 High frequencies of this allele are also observed in Thailand, China, and Taiwan where HP1–1 homozygotes, HP2–1 heterozygotes and HP2–2 homozygotes make up approximately 5–10%, 35–38%, and 53–55% of the population, respectively compared with genotype frequencies of 16%, 48%, and 36% in the northwestern European population.63 Additionally, an increased frequency of HP2 genotypes (high zonulin-producers) is seen among those with celiac disease62 and inflammatory bowel disease,62,64 compared to the general population. Investigators have also identified increased prevalence of the human HP2–2 genotype in those who experience morbidity from inflammatory disease, specifically cardiovascular and renal morbidity in T1D.65–69 This, in addition to evidence that HP2 has decreased anti-oxidant activity compared with HP1, has led to the hypothesis that the high zonulin-producing genotypes confer some degree of genetic risk for inflammatory conditions63 which could be related to production of pre-HP2, zonulin, and its effect on the intestinal barrier.

Figure 4:

The structure of pre-haptoglobin 1 (pre-HP 1) and pre-haptoglobin 2 (pre-HP 2) and their mature proteins. This figure is adapted from Fasano A (2011).59

The Zonulin Family of Proteins: Close Relatives

As preHP-2, zonulin is the first established member of a larger family of tight junction regulating proteins that also includes the recently identified properdin.70 Properdin is a soluble complement protein that has an established role in the innate immune system’s defense against infection and plays a role in both activating and regulating the alternative pathway of the complement cascade.71 In addition to zonulin’s shared similarities to properdin, phylogenetic analyses suggest that the haptoglobin-derived zonulins evolved from mannose-associated serine protease (MASP), another complement-associated protein. The α-chain of haptoglobin contains a complement control protein (CCP) domain which activates complement similarly to properdin, while the β-chain shares components with chymotrypsin-like serine proteases (SP) domain.72,73 Although zonulins share sequence homology with serine proteases, the SP-like domain of haptoglobin (and thus haptoglobin-derived zonulins) lacks the essential catalytic amino acid residues required for protease function as the active-site residues typical of the serine proteases, His57 and Ser195, are replaced in zonulins by lysine and alanine, respectively. Structure-function analyses have instead implicated this SP-like domain in receptor recognition and binding.74

Although not serine proteases, zonulins share approximately 19% amino acid sequence homology with chymotrypsin, and their genes both map on chromosome 16.70 Other than zonulin and properdin, other members of the MASP family include a series of plasminogen-related growth factors, including epidermal growth factor (EGF) with which zonulin shares the target receptor55 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), that are involved in cell growth, proliferation, differentiation and migration, and disruption of intercellular junctions.70 In addition, the expression of zonulin is not limited to the human small intestinal cells. Previously we demonstrated zonulin expression in adult and fetal human and brain tissues.75 This may implicate zonulin (and other members of the zonulin family) in key roles mechanisms regulating epithelial and endothelial cell tight junctions in other tissues.

Increased Intestinal Permeability, Zonulin as it relates to T1D:

Following release into the lumen of the small intestine, zonulin interacts with its surface receptor on the apical epithelial cells of both jejunum and distal ileum.76 Activation of the small intestinal apical membrane of non-human primates by purified zonulin, leads to reproducible and reversible tight-junction disassembly and reduced small intestine transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) – a measure of increased intestinal permeability.77 In humans, the zonulin pathway regulates the paracellular passage of macromolecules and fluid and may be involved in protection against intestinal colonization of microorganisms.78 Since the identification of zonulin, abnormally increased intestinal permeability and associated rises in serum zonulin have been characterized in many chronic inflammatory diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.58 As our group has previously shown, intestinal zonulin expression is also increased in active celiac disease.79

Using a rodent model of TID, the BioBreeding diabetic-prone (BBDP) rat, we have previously demonstrated that zonulin up-regulation occurred prior to development of increased intestinal permeability. In fact, this increase in intestinal permeability was noted before subsequent autoantibody development and clinical diabetes in this animal model of T1D.75 Blocking the zonulin-regulated increase in intestinal permeability through treatment with a zonulin receptor antagonist AT1001 (now named larazotide acetate) effectively prevented autoantibody production and greatly decreased the incidence of diabetes in treated rats.75 This proof-of-concept model suggests that zonulin dysregulation contributes to the development autoimmunity through increased intestinal permeability, and can be blocked by modulation of the zonulin pathway in an animal model of T1D. This was further illustrated by our group in 2017, when zonulin transgenic mice with the HP 2–2 genotype (zonulin producing) were subjected to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS), leading to colitis and increased mortality.60 During active colitis, these mice had an increase in duodenal and jejunal zonulin mRNA expression and this increased expression of zonulin mRNA correlated with increased intestinal permeability measured by fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran. Following treatment with zonulin receptor antagonist larazotide acetate, the intestinal permeability in the transgenic mouse decreased to baseline levels and prevented morbidity and mortality despite continued high levels of zonulin gene (mRNA) expression.60 Taken together, these data show intestinal permeability is zonulin-dependent and furthermore, pathologic increases in intestinal permeability are modifiable using zonulin receptor blockade in an animal model of T1D.75 Despite the enticing conclusion of this mechanistic research, more investigation is required to understand the role of increased intestinal permeability in humans with T1D and how this overlaps with the shared genetic risk of celiac disease.

Small Intestinal Zonulin release in Celiac Disease & The Effect of Zonulin Receptor Antagonism:

Patients with celiac disease not only demonstrate chronic gliadin-triggered inflammatory changes on small intestine biopsies, but also demonstrate increased intestinal permeability (“leakiness”) immediately following small intestinal exposure to gliadin.80 Through ex-vivo studies on duodenal biopsies from patients with celiac disease and healthy controls, Drago et al. demonstrated that intestinal exposure to gliadin not only leads to temporary increases in intestinal permeability in both individuals with and without celiac disease, but demonstrated that the patients with celiac disease exhibit an exaggerated, prolonged increase in small intestine permeability.80 These ex-vivo studies have also shown that these changes in gut permeability are secondary to a measurable small intestinal zonulin release following luminal gliadin exposure. In celiac disease, zonulin release is of significantly longer duration, persisting for 1 hour or more, compared to healthy controls, whose luminal zonulin levels returned to baseline within 30 minutes.80 This increase in luminal zonulin correlates with increased intestinal permeability as measured by a decrease in TEER.81 Our lab has shown that the zonulin receptor antagonist, larazotide acetate, effectively prevents the opening of intestinal tight junctions and halts the resultant increase in intestinal permeability. By this mechanism, larazotide acetate prevents gliadin from reaching the intestinal submucosa and triggering an inflammatory response. Clinical trials testing the ability of larazotide acetate to prevent inflammation during a gluten challenge in patients with celiac disease show significant reduction in intestinal permeability in the inpatient setting82 along with a reduction in gluten-induced symptoms, significantly blunted increases in anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (a marker of celiac disease) and the inflammatory marker INF-γ82–84 Additionally, larazotide acetate used along with a gluten-free diet decreased gastrointestinal symptoms significantly in celiac disease patients, superior to a gluten-free diet alone, and is now undergoing phase III trials.85

Increases in intestinal permeability also occur in those with T1D without celiac disease, and to a lesser extent, their first-degree relatives.54 Loss of an intact intestinal barrier accompanied by increased intestinal permeability occurs prior to the development of T1D autoimmunity in a mouse model of autoimmune T1D,75 suggesting that absence of an intact intestinal barrier should be investigated as an environmental risk factor for the development of T1D in humans.

Therefore, amongst applications to celiac disease treatment, there is potential utility for larazotide acetate in other autoimmune disease, specifically T1D. Our investigations in the BBDP rat model of T1D show that use of larazotide acetate effectively reduced the appearance of autoimmunity.75 Furthermore, increased intestinal permeability is seen both in patients with active celiac disease and in patients with T1D and their relatives.54 This adds to evidence that increased intestinal permeability by dysregulated zonulin release may contribute to the pathogenesis of both diseases.

The relationship between zonulin up-regulation and T1D autoimmunity

Increased intestinal permeability related to T1D has been studied extensively by our laboratory.53,86,87 Patients with T1D (n=339) and their first-degree relatives (n=89), all of whom tested negative for celiac disease on screening, had significantly higher baseline serum zonulin levels (Figure 5 (A)) compared to age and sex- matched controls.86 It is important to note that among patients with T1D, elevations in serum zonulin did not correlate significantly with measures of glycemic control such as hemoglobin A1c, serum glucose levels, and daily insulin dose, or the age at diagnosis of T1D. However, observed increases in serum zonulin in subjects with T1D were positively correlated with increased intestinal permeability (Figure 5 (B)) by the lactulose/mannitol (LA/MA) urine test.86 In a smaller study, 26 children with T1D without celiac disease, as determined by intestinal biopsy and by screening laboratories, demonstrated no significant difference in intestinal permeability by LA/MA test compared to age-matched controls without T1D.88 However, that same study found that T1D patients with the genotype associated with the highest risk of developing celiac disease (HLA-DQB1*02 allele) had significantly increased intestinal permeability by LA/MA test as opposed to those with T1D who were negative for the allele.88 These studies suggest that zonulin upregulation occurs in both celiac disease and a large portion of those with T1D and their relatives.

Figure 5:

(A) T1D patients (n=339) showed higher serum zonulin levels compared to both first-degree relatives (n=89) and age and sex matched controls (n=97) (B) Serum zonulin correlated with intestinal permeability as measured by the lactulose/mannitol (LA/MA) urine test in a subset of the total subject group (T1D n=36, relatives n=56, controls n=43).86

There have been two studies measuring serum zonulin levels in relatives of patients with T1D with diabetes-specific autoantibodies, a sign of early T1D autoimmunity that may precede overt disease. Sapone et al (2006) assessed serum zonulin levels between relatives of individuals with T1D with positive GADA and/or IA-2A autoantibodies (n=10) or relatives without autoantibodies (n=15) and found significantly more subjects with elevated zonulin levels in the antibody positive group, 70%, compared to 20% in the antibody negative group.86 In addition, a sub-analysis found significantly elevated serum zonulin levels after islet autoimmunity had developed, but before clinical T1D diagnosis in 3 of the 4 participants who progressed to clinical type 1 diabetes.86 So far, these are the only longitudinal data evaluating whether increases in serum zonulin precede the development of clinical T1D. The second study that evaluated serum zonulin levels in those at risk of T1D was performed in a large cohort of young children at genetic risk of T1D (the DAISY cohort) and did not report a difference between the serum zonulin levels of age-matched antibody negative children within the cohort and those with a single T1D autoantibody at the time of appearance of this antibody.89 Although the results of the DAISY study contrast with the findings from the Sapone study, it should be noted that the study populations differed in several key ways that may account for the difference in results. For instance, the DAISY study featured a much younger age group (DAISY average age 4.8 years vs. Sapone study 21.8 years) and serum zonulin levels were sampled soon after initial single antibody positivity in the DAISY study versus at the time of multiple antibody positivity in the Sapone study. While the DAISY cohort consists of infants at high genetic risk of developing T1D over time, the serum zonulin performed at the appearance of the first autoantibody captures a moment earlier in the time course in the development of autoimmunity than observed in the Sapone study, as a significant proportion of the T1D relatives in the Sapone study (70%) had two positive T1D autoantibodies (GAD plus IA-2A), indicating a more advanced degree of autoimmunity. In addition, the DAISY study compared serum zonulin levels to a control population within the DAISY cohort who also were at an increased risk of developing T1D since the controls too possessed high-risk HLA genes. Comparisons made with this control group, also at genetic risk of T1D, may make it difficult to detect differences in serum zonulin since it could not be known at the time of analysis how many children in the DAISY control group would ultimately go on to develop clinical T1D.

Taken together, the absence of zonulin elevations amongst single-antibody DAISY subjects and significantly higher zonulin level amongst multiple-autoantibody subjects suggests that children with T1D risk and advancing autoimmunity, also have a higher degree of zonulin pathway dysregulation. It is not yet well established at what time this zonulin dysregulation occurs along the “march” to autoimmunity. In our previous studies, elevated serum zonulin levels were detected in antibody-positive children at genetic risk of T1D approximately 3.5+/-0.9 years before the diagnosis of T1D.54 While this is encouraging evidence for establishing a causal role in T1D autoimmunity, it has not yet been established if zonulin dysregulation is present before the detection of autoimmunity (e.g. antibody-negative) in those who go on to develop T1D vs. those who do not. The ideal future study would assess the level of zonulin and intestinal permeability dysregulation longitudinally far before the appearance of the first T1D autoantibody and also during the “march” from tolerance to T1D autoimmunity in those children that end up developing T1D, compared to matched controls. Detecting zonulin dysregulation before the appearance of the first autoantibody would further define a cause-effect relationship, since after the appearance of the first sign of autoimmunity, compensatory mechanisms may be at play affecting serum zonulin levels. Prospective studies that evaluate and compare serum zonulin with the specific antibody type, titer, and degree of progression of disease will be crucial to tease out this relationship. In addition, there is a need for further study defining intestinal permeability and zonulin as a biomarker in those with protective genotypes for risk of T1D, as example, the presence of Aspartic acid amino acid group at position 57 in DQ alleles (ASP57) considered to be negatively associated with T1D90,91 or alternatively, in those with genes associated lower risk of celiac disease, like the HLA allele DPB1*04:0, a gene which is associated with a 29% reduction in risk of celiac disease.92 Future research should document zonulin levels longitudinally during the development of autoantibodies are required to tease out the relationship between serum zonulin and T1D autoimmunity.

Unanswered Research Questions & Future Directions

Early investigations by our group have shown that significant elevations in serum zonulin are present in both patients with T1D and their relatives, and these higher serum zonulin levels correlate with measures of increased intestinal permeability.87 Mechanistic studies also implicate zonulin up-regulation prior to the development of T1D autoimmunity, since zonulin-dependent pathologic increases in intestinal permeability precede the development of T1D autoantibodies in an animal model of T1D.75 Pre-treatment with oral zonulin receptor antagonist (larazotide acetate) in this animal model of T1D prevents zonulin-mediated increases in intestinal permeability, autoimmunity and diabetes, implicating increased permeability in the pathogenesis of T1D autoimmunity.75 In order to explore this hypothesis in humans, further studies are required to clarify correlations between serum zonulin levels and early appearance of T1D autoimmunity. To address the contrasting conclusions from prior studies,86,89 greater numbers of human subjects at risk of T1D should be studied and should be powered to allow comparisons between high vs. low/moderate genetic risk of T1D, vs. those with protective genetic factors. In addition, serum zonulin levels should be studied longitudinally in those who develop T1D to determine the timing and appearance of zonulin as a potential biomarker of increased intestinal permeability. A current study by the authors of this review will evaluate for zonulin upregulation among first-degree relatives of T1D subjects with 0, 1 and 2 or more T1D autoantibodies to characterize the timing of zonulin abnormalities accompanying the progression of T1D autoimmunity. Plasma zonulin level will be correlated with both degree of T1D autoimmunity – the type and number of islet antibodies, and haptoglobin genotype (HP 1–1, 2–1, or 2–2). Prior investigations by our group have shown that serum zonulin is a biochemical marker for pathologic increases in intestinal permeability86 but confirmatory studies are needed in humans to clarify the timing of this zonulin increase in relation to specific physiologic environments (like hypoglycemia) and dietary exposures other than gluten as other potential triggers of small intestinal zonulin release.

The recent discovery that zonulin (as pre-HP2) is simply the archetypal member of a larger family of intestinal permeability-regulating proteins, should spark further mechanistic research featuring another prominent member of the zonulin family: properdin.70 Properdin has been previously characterized as a key component in the alternative pathway of complement activation.79 Since the complement system is important in innate immunity and activation of the immune system inflammatory responses, the discovery that now two members of the zonulin family, properdin and pre-HP2 share striking sequence homology70 should further encourage involvement of immunologists in small intestine tight-junction research. Further studies should aim to define each zonulin protein’s physiologic role in the closely regulated small intestinal tight junction. Since pre-HP2 is only present in certain individuals possessing the HP2 gene, clarification of the type and quantity of zonulin proteins expressed based on an individual’s haptoglobin genotype would also contribute to our understanding of zonulin and properdin’s role in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Recent strides in genetic research have further clarified the relationship between the shared genetic risk susceptibility in celiac disease and T1D by identification of shared high risk HLA, non-HLA and SNP genes.33,34 This research, as well as epidemiological studies showing a notable increase in T1D diagnosis that is not explained by an increased frequency of the genes at highest risk of T1D7–9 is supportive of a hypothesis that a currently unknown environmental trigger may have prompted increases in autoimmunity in members of the population with a previously lower genetic risk profile. These associations will need to be further clarified by studies that evaluate for genes that coincide with both zonulin upregulation and shared genetic risk of T1D and celiac disease—potentially implicating a zonulin-related mechanism in T1D pathogenesis.

While more research is required to clarify zonulin as a potential putative biomarker of T1D autoimmunity, the existence of an oral medication that could potentially modify the mechanism of increased intestinal permeability in certain patients at risk of T1D adds promise to this research. These summarized findings of current literature should prompt continued investigations into zonulin as it relates T1D in order to determine its role in the development of T1D autoimmunity.

Statement of Originality.

This manuscript is an original unpublished work and is not being submitted for publication elsewhere at the same time. Several of the figures (Figure 2, Figure 4, and Figure 5) have been published by the lead author of this manuscript previously and copyright clearance has been obtained (Figures 4 & 5) and requested (Figure 2) for all figures. Publications with the figures have been adequately cited in the figure legends, and the legends themselves are have been modified slightly but not extensively in order to depict the original content. There are no prior duplicate publications or submissions elsewhere of any part of the work included in the manuscript.

Figure 5 has been enhanced in order to improve brightness and contrast and to improve the resolution of the image. These modifications have been applied equally across the image and does not obscure, eliminate or misrepresent any information in the original image. The original image will be provided to the editorial staff in the unedited form.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by NIDDK (1F32DK117607 to LW).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

AF is a stock holder with Alba Therapeutics, a consultant with Inova Diagnostics with regards to diagnosis of celiac disease, a consultant with Innovate Biopharmaceuticals, Inc and has a speaking agreement with Mead Johnson Nutrition. AF is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Viome. No grants, honoraria or royalties were received supporting the writing of the paper. MD and LWH have no financial or other potential conflicts of interest to report.

Statement of Ethics

No ethical concerns have been raised during the creation of this review article.

References:

- 1.Nathan D, Cleary P, Backlund J. Intensive Diabetes Treatment and Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(25):2643–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, et al. Prevalence of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Among Children and Adolescents From 2001 to 2009. JAMA. 2014;311(17):1778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imperatore G, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, et al. Projections of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Burden in the U.S. Population Aged <20 Years Through 2050: Dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and population growth. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2515–2520. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Achenbach P, Warncke K, Reiter J, et al. Stratification of Type 1 Diabetes Risk on the Basis of Islet Autoantibody Characteristics. Diabetes. 2004;53(2):384–392. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler A-G, Pflueger M, Winkler C, et al. Accelerated progression from islet autoimmunity to diabetes is causing the escalating incidence of type 1 diabetes in young children. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2011;37(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingley PJ, Boulware DC, Krischer JP. The implications of autoantibodies to a single islet antigen in relatives with normal glucose tolerance: development of other autoantibodies and progression to type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;59(3):542–549. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3830-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillespie KM, Bain SC, Barnett AH, et al. The rising incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes and reduced contribution of high-risk HLA haplotypes. The Lancet. 2004;364(9446):1699–1700. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17357-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vehik K, Hamman RF, Lezotte D, et al. Trends in High-Risk HLA Susceptibility Genes Among Colorado Youth With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1392–1396. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fourlanos S, Varney MD, Tait BD, et al. The Rising Incidence of Type 1 Diabetes Is Accounted for by Cases With Lower-Risk Human Leukocyte Antigen Genotypes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1546–1549. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang GB, Yoon JS, Park KJ, Lee HS, Hwang JS. Prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in patients with type 1 diabetes: a long-term follow-up study. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2018;23(1):33–37. doi: 10.6065/apem.2018.23.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pham-Short A, Donaghue KC, Ambler G, Phelan H, Twigg S, Craig ME. Screening for Celiac Disease in Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. PEDIATRICS. 2015;136(1):e170–e176. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trynka G, Hunt KA, Bockett NA, et al. Dense genotyping identifies and localizes multiple common and rare variant association signals in celiac disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43(12):1193–1201. doi: 10.1038/ng.998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roizen JD, Bradfield JP, Hakonarson H. Progress in Understanding Type 1 Diabetes Through Its Genetic Overlap with Other Autoimmune Diseases. Curr Diab Rep 2015;15(11):102. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0668-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimura K, Miura J, Kawamoto M, Kawaguchi Y, Yamanaka H, Uchigata Y. Genetic differences between type 1 diabetes with and without other autoimmune diseases. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34(7):e3023. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noble JA. Immunogenetics of type 1 diabetes: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2015;64:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert AP, Gillespie KM, Thomson G, et al. Absolute Risk of Childhood-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Defined by Human Leukocyte Antigen Class II Genotype: A Population-Based Study in the United Kingdom. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89(8):4037–4043. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonifacio E, Beyerlein A, Hippich M, et al. Genetic scores to stratify risk of developing multiple islet autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes: A prospective study in children. PLOS Medicine. 2018;15(4):e1002548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redondo MJ, Steck AK, Pugliese A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes. 2017;19(3):346–353. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rich SS. Genetics and its potential to improve type 1 diabetes care. Current Opinion in Endocrinology & Diabetes and Obesity. 2017;24(4):279–284. doi: 10.1097/med.0000000000000347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA, et al. Staging Presymptomatic Type 1 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1964–1974. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O, et al. Seroconversion to Multiple Islet Autoantibodies and Risk of Progression to Diabetes in Children. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wherrett DK, Chiang JL, Delamater AM, et al. Defining Pathways for Development of Disease-Modifying Therapies in Children With Type 1 Diabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1975–1985. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenbaum CJ, Beam CA, Boulware D, et al. Fall in C-Peptide During First 2 Years From Diagnosis: Evidence of at Least Two Distinct Phases From Composite Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Data. Diabetes. 2012;61(8):2066–2073. doi: 10.2337/db11-1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao W, Gitelman S, DiMeglio LA, Boulware D, Greenbaum CJ. Fall in C-Peptide During First 4 Years From Diagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes: Variable Relation to Age, HbA 1c, and Insulin Dose. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(10):1664–1670. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vehik K, Dabelea D. The changing epidemiology of type 1 diabetes: why is it going through the roof? Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2010;27(1):3–13. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steck AK, Armstrong TK, Babu SR, Eisenbarth GS. Stepwise or Linear Decrease in Penetrance of Type 1 Diabetes With Lower-Risk HLA Genotypes Over the Past 40 Years. Diabetes. 2011;60(3):1045–1049. doi: 10.2337/db10-1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cerutti F, Bruno G, Chiarelli F, Lorini R, Meschi F, Sacchetti C. Younger Age at Onset and Sex Predict Celiac Disease in Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: An Italian multicenter study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1294–1298. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craig M, Prinz N, Boyle C, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in 52,721 youth with T1DM: international comparison across three continents. Yearbook of Paediatric Endocrinology. September 2018. doi: 10.1530/ey.15.10.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elfström P, Sundström J, Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review with meta-analysis: associations between coeliac disease and type 1 diabetes. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2014;40(10):1123–1132. doi: 10.1111/apt.12973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2012;54(1):136–160. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0b013e31821a23d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lernmark Å Environmental factors in the etiology of type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, and narcolepsy. Pediatric Diabetes. 2016;17:65–72. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagopian W, Lee H-S, Liu E, et al. Co-occurrence of Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease Autoimmunity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5):e20171305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutierrez-Achury J, Romanos J, Bakker SF, et al. Contrasting the Genetic Background of Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease Autoimmunity. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Supplement 2):S37–S44. doi: 10.2337/dcs15-2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smyth DJ, Plagnol V, Walker NM, et al. Shared and Distinct Genetic Variants in Type 1 Diabetes and Celiac Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(26):2767–2777. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0807917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kupfer SS, Jabri B. Pathophysiology of Celiac Disease. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 2012;22(4):639–660. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solid L, Lie B. Celiac Disease Genetics: Current Concepts and Practical Applications. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2005;3(9):843–851. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00532-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu E, Lee H-S, Aronsson CA, et al. Risk of pediatric celiac disease according to HLA haplotype and country. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(1):42–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leonard MM, Sapone A, Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac Disease and Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity. JAMA. 2017;318(7):647. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aronsson CA, Lee H-S, Segerstad EMH af, et al. Association of Gluten Intake During the First 5 Years of Life With Incidence of Celiac Disease Autoimmunity and Celiac Disease Among Children at Increased Risk. JAMA. 2019;322(6):514–523. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmid S, Koczwara K, Schwinghammer S, Lampasona V, Ziegler A-G, Bonifacio E. Delayed exposure to wheat and barley proteins reduces diabetes incidence in non-obese diabetic mice. Clin Immunol. 2004;111(1):108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uusitalo U, Lee H-S, Andrén Aronsson C, et al. Early Infant Diet and Islet Autoimmunity in the TEDDY Study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(3):522–530. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hakola L, Miettinen ME, Syrjälä E, et al. Association of Cereal, Gluten, and Dietary Fiber Intake With Islet Autoimmunity and Type 1 Diabetes. JAMA Pediatr. August 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lund-Blix NA, Dong F, Mårild K, et al. Gluten Intake and Risk of Islet Autoimmunity and Progression to Type 1 Diabetes in Children at Increased Risk of the Disease: The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):789–796. doi: 10.2337/dc18-2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serena G, Camhi S, Sturgeon C, Yan S, Fasano A. The Role of Gluten in Celiac Disease and Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2015;7(9):7143–7162. doi: 10.3390/nu7095329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Herrath MG, Fujinami RS, Whitton JL. Microorganisms and autoimmunity: making the barren field fertile? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1(2):151–157. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bach J-F. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKinney PA, Okasha M, Parslow RC, et al. Early social mixing and childhood Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a case-control study in Yorkshire, UK. Diabet Med. 2000;17(3):236–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall K, Frederiksen B, Rewers M, Norris JM. Daycare attendance, breastfeeding, and the development of type 1 diabetes: the diabetes autoimmunity study in the young. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:203947. doi: 10.1155/2015/203947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rook G a. W, Brunet LR. Microbes, immunoregulation, and the gut. Gut. 2005;54(3):317–320. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.053785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X, Atkinson MA. The role for gut permeability in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes--a solid or leaky concept? Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(7):485–492. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaarala O, Atkinson MA, Neu J. The “perfect storm” for type 1 diabetes: the complex interplay between intestinal microbiota, gut permeability, and mucosal immunity. Diabetes. 2008;57(10):2555–2562. doi: 10.2337/db08-0331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner JR. Molecular Basis of Epithelial Barrier Regulation. The American Journal of Pathology. 2006;169(6):1901–1909. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Visser J, Rozing J, Sapone A, Lammers K, Fasano A. Tight Junctions, Intestinal Permeability, and Autoimmunity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1165(1):195–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04037.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sapone A, de Magistris L, Pietzak M, et al. Zonulin Upregulation Is Associated With Increased Gut Permeability in Subjects With Type 1 Diabetes and Their Relatives. Diabetes. 2006;55(5):1443–1449. doi: 10.2337/db05-1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tripathi A, Lammers KM, Goldblum S, et al. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(39):16799–16804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906773106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lammers KM, Lu R, Brownley J, et al. Gliadin Induces an Increase in Intestinal Permeability and Zonulin Release by Binding to the Chemokine Receptor CXCR3. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):194–204.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asmar RE, Panigrahi P, Bamford P, et al. Host-dependent zonulin secretion causes the impairment of the small intestine barrier function after bacterial exposure. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(5):1607–1615. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sturgeon C, Fasano A. Zonulin, a regulator of epithelial and endothelial barrier functions, and its involvement in chronic inflammatory diseases. Tissue Barriers. 2016;4(4):e1251384. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2016.1251384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fasano A Zonulin and Its Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function: The Biological Door to Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Cancer. Physiological Reviews. 2011;91(1):151–175. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sturgeon C, Lan J, Fasano A. Zonulin transgenic mice show altered gut permeability and increased morbidity/mortality in the DSS colitis model. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2017;1397(1):130–142. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miranda-Ribera A, Ennamorati M, Serena G, et al. Exploiting the Zonulin Mouse Model to Establish the Role of Primary Impaired Gut Barrier Function on Microbiota Composition and Immune Profiles. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2233. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papp M, Foldi I, Nemes E, et al. Haptoglobin Polymorphism: A Novel Genetic Risk Factor for Celiac Disease Development and Its Clinical Manifestations. Clinical Chemistry. 2008;54(4):697–704. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.098780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Langlois MR, Delanghe JR. Biological and clinical significance of haptoglobin polymorphism in humans. Clin Chem. 1996;42(10):1589–1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Márquez L, Shen C, Cleynen I, et al. Effects of haptoglobin polymorphisms and deficiency on susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease and on severity of murine colitis. Gut. 2011;61(4):528–534. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.240978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Costacou T, Ferrell RE, Orchard TJ. Haptoglobin Genotype: A Determinant of Cardiovascular Complication Risk in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1702–1706. doi: 10.2337/db08-0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Costacou T, Ferrell RE, Ellis D, Orchard TJ. Haptoglobin Genotype and Renal Function Decline in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58(12):2904–2909. doi: 10.2337/db09-0874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vardi M, Blum S, Levy AP. Haptoglobin genotype and cardiovascular outcomes in diabetes mellitus — natural history of the disease and the effect of vitamin E treatment. Meta-analysis of the medical literature. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2012;23(7):628–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Llauradó G, Gutiérrez C, Giménez-Palop O, et al. Haptoglobin genotype is associated with increased endothelial dysfunction serum markers in type 1 diabetes. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;45(9):932–939. doi: 10.1111/eci.12487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Costacou T, Orchard TJ. The Haptoglobin genotype predicts cardio-renal mortality in type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2016;30(2):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scheffler L, Crane A, Heyne H, et al. Widely Used Commercial ELISA Does Not Detect Precursor of Haptoglobin2, but Recognizes Properdin as a Potential Second Member of the Zonulin Family. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2018;9. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blatt AZ, Pathan S, Ferreira VP. Properdin: a tightly regulated critical inflammatory modulator. Immunological Reviews. 2016;274(1):172–190. doi: 10.1111/imr.12466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wicher KB, Fries E. Haptoglobin, a hemoglobin-binding plasma protein, is present in bony fish and mammals but not in frog and chicken. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(11):4168–4173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508723103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kurosky A, Barnett DR, Lee TH, et al. Covalent structure of human haptoglobin: a serine protease homolog. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1980;77(6):3388–3392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nielsen MJ, Petersen SV, Jacobsen C, et al. A Unique Loop Extension in the Serine Protease Domain of Haptoglobin Is Essential for CD163 Recognition of the Haptoglobin-Hemoglobin Complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;282(2):1072–1079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m605684200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Watts T, Berti I, Sapone A, et al. Role of the intestinal tight junction modulator zonulin in the pathogenesis of type I diabetes in BB diabetic-prone rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102(8):2916–2921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500178102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fasano A Intestinal epithelial tight junctions as targets for enteric bacteria-derived toxins. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2004;56(6):795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Human zonulin, a potential modulator of intestinal tight junctions. - PubMed - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11082037. Accessed November 26, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.El Asmar R, Panigrahi P, Bamford P, et al. Host-dependent zonulin secretion causes the impairment of the small intestine barrier function after bacterial exposure. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(5):1607–1615. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fasano A, Not T, Wang W, et al. Zonulin, a newly discovered modulator of intestinal permeability, and its expression in coeliac disease. The Lancet. 2000;355(9214):1518–1519. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02169-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Drago S, El Asmar R, Di Pierro M, et al. Gliadin, zonulin and gut permeability: Effects on celiac and non-celiac intestinal mucosa and intestinal cell lines. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;41(4):408–419. doi: 10.1080/00365520500235334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fasano A Zonulin, regulation of tight junctions, and autoimmune diseases. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1258(1):25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06538.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Paterson BM, Lammers KM, Arrieta MC, Fasano A, Meddings JB. The safety, tolerance, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of single doses of AT-1001 in coeliac disease subjects: a proof of concept study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2007;26(5):757–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Abdallah HZ, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind Study of Larazotide Acetate to Prevent the Activation of Celiac Disease During Gluten Challenge. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107(10):1554–1562. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kelly CP, Green PHR, Murray JA, et al. Larazotide acetate in patients with coeliac disease undergoing a gluten challenge: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2012;37(2):252–262. doi: 10.1111/apt.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Green PHR, et al. Larazotide Acetate for Persistent Symptoms of Celiac Disease Despite a Gluten-Free Diet: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(7):1311–1319.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sapone A, de Magistris L, Pietzak M, et al. Zonulin Upregulation Is Associated With Increased Gut Permeability in Subjects With Type 1 Diabetes and Their Relatives. Diabetes. 2006;55(5):1443–1449. doi: 10.2337/db05-1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sapone A, Counts D, Kryszak D, et al. Effect of gluten-containing diet on serum zonulin and intestinal permeability in type 1 diabetes children and their relatives. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2005;41(4):558. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000182065.05139.82 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuitunen M, Saukkonen T, Ilonen J, Åkerblom HK, Savilahti E. Intestinal Permeability to Mannitol and Lactulose in Children with Type 1 Diabetes with the HLA-DQB1*02 Allele. Autoimmunity. 2002;35(5):365–368. doi: 10.1080/0891693021000008526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]