SYNOPSIS

Individuals with scleroderma have an increased risk of cancer compared to the general population. This heightened risk may be from chronic inflammation and tissue damage, malignant transformation provoked by immunosuppressive therapies, or a common inciting factor. In unique subsets of scleroderma patients, there is a close temporal relationship between the onset of cancer and scleroderma, suggesting cancer-induced autoimmunity. In this review, we discuss the potential mechanistic links between cancer and scleroderma, the serological and clinical risk factors associated with increased cancer risk in patients with scleroderma, and implications for cancer screening.

Keywords: Scleroderma, malignancy, autoantibodies, epidemiology, cancer screening

Epidemiology of cancer in patients with scleroderma

Most epidemiologic studies have shown that individuals with scleroderma have an increased age- and sex-adjusted risk of developing cancer, with this risk generally ranging from 1.5 to 4 times higher than that of the general population1–14. While it is beyond the scope of this review to discuss all of these studies, we would like to draw particular attention to three meta-analyses which have both quantified the magnitude of cancer risk and examined the particular tumor types that are enriched in scleroderma.

Onishi and colleagues examined six population-based cohort studies comprising a total of 6,641 people with scleroderma from Australia, Northern Europe, Taiwan, and the United States9. They found a pooled standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.41 for cancer overall, with a trend towards a greater risk in men than women (SIR 1.85 versus 1.33 respectively). With regard to particular tumors types which were enriched in these cohorts, they found an increased risk of lung, liver, and hematologic cancers overall, as well as an increased risk of bladder cancer in women and non-melanomatous skin cancer in men. Conversely, there was no increased risk of breast cancer, though the authors excluded cases of cancer which were diagnosed prior to the onset of scleroderma. The temporal clustering of breast cancer and scleroderma, with either diagnosis arising shortly before the other, has been well described in the literature and is discussed in more detail later in this review15–18. They likewise did not find an increased risk of other sex-specific cancers such as prostate, cervical, or uterine cancer. A contemporaneous meta-analysis by Zhang and colleagues found similar results, with increased SIRs for lung cancer, hematopoietic cancer, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but not breast cancer14.

Bonifazi and colleagues conducted the largest meta-analysis to date using 16 observational studies, which included most of the articles examined by Onishi and Zhang as above2. Compared to the general population, the relative risk of cancer in scleroderma was 1.75, with particularly strong associations between scleroderma and lung cancer (RR 4.35) and hematologic neoplasms (RR 2.24). Of the included studies assessing liver cancer or esophageal cancer, all showed an increased risk with SIRs ranging from 3.30–7.35 and 2.86–35.0, respectively. Available data for the incidence of stomach, pancreas, skin, and oral cavity cancers were conflicting, and the authors again did not find an increased risk of any sex-specific cancers.

The development of particular tumor types in scleroderma may in part depend on the severity and pattern of a given individual’s end organ involvement and/or the immunosuppressive medications they have received, though these associations have not been consistently characterized in the literature. These potential mechanisms linking cancer and scleroderma are discussed in more detail below.

Other demographic and phenotypic features of scleroderma which have been variably associated with an increased risk of cancer in early studies include older age of onset of scleroderma 1,19–22, male sex6,8,9, smoking history23, and diffuse cutaneous involvement5, though these findings have not been consistently reproduced. Scleroderma autoantibody status, particularly anti-RNA polymerase III (anti-POLR3) positivity, has a dramatic effect on the overall risk and timing of cancer and may account for the discordant results from previous studies which did not control for this effect. This aspect of risk stratification is discussed in more detail elsewhere in this review.

Potential mechanisms linking cancer and scleroderma

The relationship between cancer and scleroderma is likely complex and bidirectional. Cancers may emerge around the time of scleroderma onset or years after scleroderma diagnosis. These temporal relationships raise the question of whether malignancies or cancer treatments could trigger the development of scleroderma in some patients, whereas scleroderma or scleroderma therapies could increase the risk of subsequent cancer development in others. It is also possible that both diseases share a common inciting exposure or genetic predisposition24.

Data suggest that scleroderma disease activity and damage, particularly within individual organs, may predispose to malignant transformation within the same target tissues. For instance, patients with scleroderma may have a higher risk of esophageal cancer associated with severe reflux and Barrett’s esophagus, lung cancer in the context of known interstitial lung disease (ILD), liver cancer if there is overlap primary biliary cirrhosis, or thyroid cancer if there is autoimmune thyroiditis1,12,25,26. Data conflict as to whether scleroderma-ILD is a risk factor for lung cancer1,6,9,23,27, but the higher risk of lung cancers in patients with anti-topoisomerase 1 antibodies and reduced forced vital capacity is suggestive28. In a Japanese cohort of scleroderma patients, risk factors for cancer were examined; all 10 lung cancer cases occurred in patients with ILD4. Interestingly, of the 4 patients who had autopsies in this study, the primary lung cancer was found in tissue affected by ILD in all cases.

Another possibility is that cytotoxic therapies used to treat scleroderma could increase the risk of subsequent cancer. Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent that has been used to treat severe scleroderma cutaneous and pulmonary disease. Data from vasculitis, scleroderma, and lupus suggest that the risk of hematologic and bladder cancers may be increased with exposure to cyclophosphamide, in particular with higher cumulative doses and in smokers29–33. Increasingly, mycophenolate mofetil is used to treat active cutaneous disease, ILD, and myositis in scleroderma. The data on cancer risk with mycophenolate in the rheumatic diseases is less clear, as most of the studies in this area are from the transplant area where patients are often treated with combinations of immunosuppressive drugs. Data in the transplantation literature conflict as to whether there is a higher risk of lymphoproliferative diseases and non-melanoma skin cancers34–37, with one recent report suggesting a higher risk of primary CNS lymphoma38. The data on cancer risk with immunosuppressive drugs in scleroderma patients are limited. In our cohort, we have not observed an increased risk of cancer with immunosuppressive drug use including cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate mofetil22. Whether these agents could directly promote malignant transformation is unclear. In the lupus literature, it has been postulated that immunosuppressive drugs may inhibit clearance of oncogenic viral infections, thereby increasing the risk of virus-associated cancers24,33. For discussion of other immunomodulatory agents commonly used in the rheumatic diseases and cancer risk, we refer the reader to a recent review by Cappelli et al39.

It is also important to note that patients with scleroderma may have a high cumulative exposure to ionizing radiation from medical tests over time, including plain radiographs, computed tomography, and nuclear medicine studies40. This could potentially increase the risk of cancer development.

A subset of patients develops scleroderma after cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cancer therapeutics, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and immunotherapy, may increase the risk of developing scleroderma. Case reports describe the development of scleroderma-like fibrosing syndromes and critical digital ischemia after exposure to bleomycin, gemcitabine, paclitaxel and carboplatin41–46. Radiation therapy may trigger both cutaneous and pulmonary fibrosis; most reports describe localized scleroderma or exaggerated fibrosis developing in patients with known scleroderma1,47–49. It remains unclear whether de novo scleroderma could be a consequence of radiation exposure. A newer cancer therapeutic class, immune checkpoint inhibitors, works by blocking negative costimulatory receptors or ligands on T cells and antigen presenting cells. These drugs can cause nonspecific T cell activation and have resulted in a number of rheumatic immune related adverse events. Recently, features resembling scleroderma have been reported after therapy with pembrolizumab or nivolumab (both PD-1 inhibitors)50–53. Critical digital ischemia after immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has also been reported54.

A close temporal relationship between the onset of cancer and scleroderma has been found in certain individuals, raising the question of whether scleroderma could be a paraneoplastic disease. This was initially observed in case reports and case series across a range of tumor types, though with particularly striking temporal clustering of breast cancer and scleroderma12,15–18. In one series, the breast cancer-scleroderma interval was 12 months or less in 27 of 44 individuals (61.4%), with simultaneous disease onset in 11 (25%)17. Nearly half of this cohort was diagnosed with breast cancer prior to the onset of scleroderma. Further supporting the idea of scleroderma as a paraneoplastic phenomenon are reports of cancer treatment resulting in dramatic improvements in scleroderma55,56. While it has been challenging to discern whether this improvement was due to cancer treatment or simply the use of potent immunosuppression, a recent report of a patient improving solely with resection of tumor suggests that cancer itself may be a driver of scleroderma57.

Unique autoantibodies identify patient subgroups with a high risk of cancer-associated scleroderma

Given data suggesting that scleroderma could be a paraneoplastic disease, our group hypothesized that tumor antigen expression might be associated with scleroderma-specific autoantibody responses. In an initial study of 23 individuals with both cancer and scleroderma, we found that those with anti-POLR3 antibodies had a significantly shorter cancer-scleroderma interval compared to those with anti-topoisomerase 1 or anti-centromere antibodies (medians of −1.2 years, +13.4 years and +11.1 years, respectively)58. Furthermore, participants who had anti-POLR3 antibodies had robust nucleolar expression of RNA polymerase III in their cancerous cells, which was not found in cancer cells from the other antibody groups or in healthy control tissues.

This association between anti-POLR3 antibodies and increased risk of concurrent cancer and scleroderma onset has since been reproduced in multiple international cohorts including from Australia, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom20,21,59,60. Recently, this finding was validated in the European League Against Rheumatism Scleroderma Trials and Research group (EUSTAR) cohort19. A total of 4,986 individuals with scleroderma from 13 participating EUSTAR centers were included, and 158 participants with anti-POLR3 antibodies were compared to 199 anti-POLR3 negative controls matched for sex, cutaneous phenotype, age of scleroderma onset, and disease duration. Cancer was significantly more common in the anti-POLR3 positive group (17.7% versus 9.0%), particularly with respect to cancers diagnosed within two years of scleroderma onset (9.0% versus 2.5%). Individuals with a synchronous onset of cancer and scleroderma in the setting of anti-POLR3 antibodies were significantly older at age of scleroderma onset and more likely to have diffuse cutaneous disease. The risk of concurrent onset non-breast cancers and scleroderma was also significantly higher in men than women. These demographic and phenotypic risk factors are consistent with the findings from early epidemiologic studies as discussed above.

The findings in our pilot study have also been validated using a much larger cohort of 1,044 individuals from the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center cohort22. Logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationship of overall cancer risk and a shortened cancer-scleroderma interval with autoantibody status, demographic features, and scleroderma phenotypic features. Once again, anti-POLR3 positivity was associated with a significantly increased risk of cancer diagnosis within 2 years of scleroderma onset (odds ratio 5.08). There was also an increased temporal clustering of cancer and scleroderma in the group of participants who were negative for anti-centromere, anti-topoisomerase I, and anti-POLR3 antibodies (hereafter referred to as “CTP-negative”).

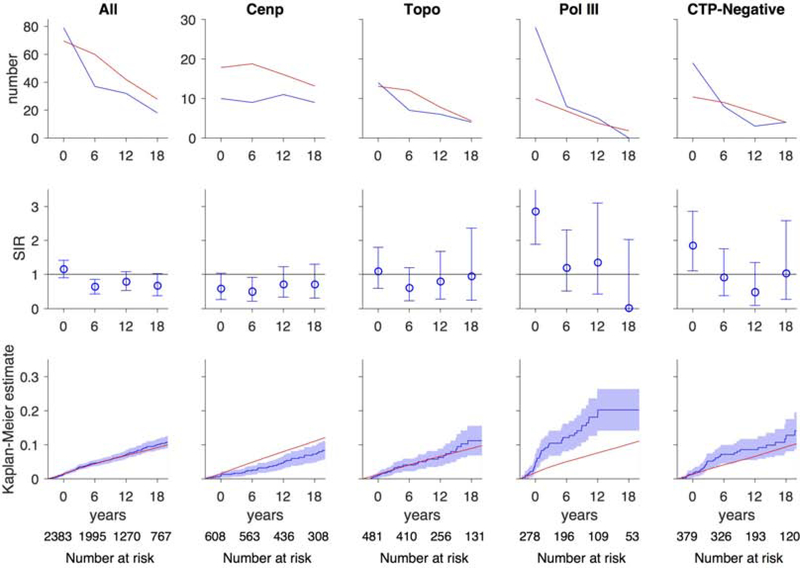

A major limitation of these prior studies was that cancer risk was investigated in scleroderma patients with a given autoantibody compared to scleroderma patients who were negative for that specificity. This study design does not permit determination of the magnitude or types of cancer at high risk compared to the general population – information that is needed to inform cancer screening strategies in scleroderma. To address this limitation, we examined cancer incidence within 3 years of scleroderma onset (i.e. cancer-associated scleroderma) in distinct serological and phenotypic groups and compared this to the US SEER cancer registry61. Of 2,383 participants with scleroderma, 205 (~9%) had a history of cancer. Patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies and CTP-negative patients had a 2.8-fold and 1.8-fold increased risk of cancer within 3 years of scleroderma onset, respectively (Figure 1). Within 3 years of scleroderma onset, patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies and diffuse cutaneous disease had a higher risk of breast cancer (SIR 5.14), prostate cancer (SIR 7.17) and tongue cancer (SIR 43.9), whereas patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies and limited cutaneous disease had an increased risk of lung cancer (SIR 10.4). Similarly within 3 years of scleroderma onset, CTP-negative patients with limited scleroderma had a higher risk of breast cancer (SIR 4.44) and melanoma (SIR 7.10), and CTP-negative patients with diffuse scleroderma had an increased risk of tongue cancer (SIR 40.5). Interestingly when examining overall cancer risk, patients with anti-centromere antibodies had a significantly lower risk of cancer than that expected in the general population (SIR 0.59; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Risk of all cancers over time.

In each graph, the x-axis reflects time from scleroderma onset (defined as time zero). Top and middle rows, each time window represents a 6-year period (±3 years); for example, data plotted at time zero reflects cancer risk within ±3 years of scleroderma onset. The number at risk for each time window is denoted at the bottom of the graph. Top row, the observed number of cancer cases (blue) is presented in comparison with the number of cancer cases that are expected based on SEER data (red). Middle row, the ratio between the observed and expected cancer cases is presented as a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) along with its 95% confidence interval. Values of 1 denote a cancer risk equivalent to that of the background population. Bottom row, the cumulative incidence of cancer among scleroderma patients (solid blue line) starting at 3 years before scleroderma onset is presented with 95% confidence intervals (shaded blue region). Red lines represent the expected cumulative incidence of cancer based on SEER data for the general population. Scleroderma patients with anti-centromere antibodies appear to have a decreased risk of cancer over time. Scleroderma patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies and the CTP-Negative group have an increased risk of cancer that is prominent at scleroderma onset. The cumulative incidence of cancer is significantly higher than that observed in the general population among patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies. Adapted with permission61.

From Igusa T, Hummers LK, Visvanathan K, et al. Autoantibodies and scleroderma phenotype define subgroups at high-risk and low-risk for cancer. Ann Rheum Dis. 22018;77(8): 1179–1186; with permission.

It is important to note that the CTP-negative subgroup in scleroderma is a heterogenous population that likely consists of patients with many different scleroderma immune responses. It remains an important priority to identify the distinct subpopulations within CTP-negative patients, as this may guide risk stratification for cancer. Recently, our group has focused on autoantibody discovery in CTP-negative individuals in whom cancers were detected close to the time of scleroderma onset. In an initial investigation, Phage Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (PhIP-Seq) was utilized for autoantibody discovery in participants who were either CTP-negative with synchronous cancer and scleroderma, or had anti-POLR3 antibodies with or without cancer62. This method identified antibodies against the RNA Binding Region Containing 3 (RNPC3), a component of the minor spliceosome complex, in 4 of 16 (25%) in the CTP-negative group and in none (0 of 32) in the anti-POLR3-positive group. These findings were subsequently reproduced in a larger population of 318 people with scleroderma and cancer63. Among them, a total of 12 (3.8%) had anti-RNPC3 antibodies. Compared to those with anti-centromere antibodies, individuals with anti-RNPC3 or anti-POLR3 antibodies had a significantly higher risk of developing cancer within two years of scleroderma onset, with odds ratios of 4.3 and 4.5 respectively. Interestingly, 66.7% of the cancers in the anti-RNPC3 group were gynecologic tumors in women, with 50% having breast cancer, though this did not reach statistical significance across antibody subgroups due to small sample sizes.

The association between scleroderma-specific antibodies and cancer risk is likely limited to individuals who manifest clinical features of autoimmune disease and thus far does not appear to inform cancer risk in the general population. In a case control study of 50 women with breast cancer and 50 matched healthy controls (all without rheumatologic disease), all participants were negative for anti-POLR3 antibodies except for one control who was only borderline positive64. Similarly, anti-RNPC3 antibodies have not been detected in small comparison cohorts of healthy controls, patients with pancreatic cancer without rheumatic disease, and lupus patients with cancer63.

Evidence for a model of cancer-induced autoimmunity

The striking co-occurrence of cancer and scleroderma onset in individuals with anti-POLR3 antibodies suggests a possible mechanistic link between the two disease processes and raised the question that cancer might be the trigger initiating autoimmunity in this subset of people. This was investigated in a landmark study of tumors obtained from 16 scleroderma patients, eight of whom had anti-POLR3 antibodies, and eight lacking these antibodies (they had antibodies against topoisomerase 1 or centromere, the two other prominent scleroderma antibody specificities)65. In 6 of 8 (75%) of cancers from the anti-POLR3-positive patients, alterations in the POLR3A gene locus were found. In contrast, none were detected in the tumors from the other eight patients. Of the six patients with genetic abnormalities in POLR3A, three were somatic mutations; in each, this resulted in a single amino acid change (different in each patient). Furthermore, in two of these three patients, T cells that reacted with the mutated neoantigens were detected in peripheral blood. Given the rarity of POLR3A mutations in cancer, these findings are consistent with initiation of the anti-POLR3 immune response by such somatic mutations. A second kind of genetic alteration was found in this study: 5/8 patients had loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the POLR3A gene locus. Since LOH was not detected in the cancers from the eight patients lacking anti-POLR3 antibodies, it is likely that the anti-POLR3 antibody response participates in shaping cancer evolution.

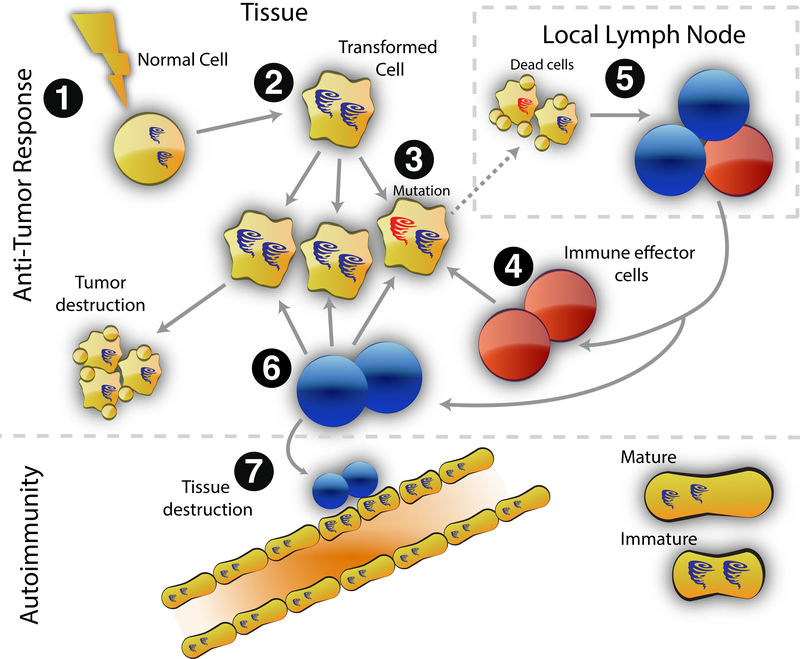

Interestingly, anti-POLR3 antibodies in the patients with somatic mutations cross-reacted with both the mutated and wild-type RNA polymerase III protein65. These data suggest a model of cancer-induced autoimmunity in scleroderma, where the anti-POLR3 immune response is initiated against the mutated protein in the cancer (that is, an anti-tumor immune response), followed by subsequent spreading to the wild type protein (Figure 2)66. In the susceptible host, this cross-reactive immune response could damage target tissue, and become self-sustaining, resulting in scleroderma propagation.

Figure 2. Model of cancer-induced autoimmunity.

Transformation of normal cells (1) may result in gene expression patterns that resemble immature cells involved in tissue healing (2). Occasionally, autoantigens become mutated (3); these are not driver mutations, and not all cancer cells have them. The first immune response is directed against the mutated form of the antigen (4), and may spread to the wild-type version (5). Immune effector cells directed against the mutant (depicted in red) delete exclusively cancer cells containing the mutation (6). Immune effector cells directed against the wild type (depicted in blue) delete cancer cells without the mutation and also cross-react with the patient’s own tissues (particularly immature cells expressing high levels of antigen, found in damaged/repairing tissue) (7). Once autoimmunity has been initiated, the disease is self-propagating. Immature cells (expressing high antigen levels) that repair the immune-mediated injury can themselves become the targets of the immune response, sustaining an ongoing cycle of damage/repair that provides the antigen source that fuels the autoimmune response.

From Shah AA, Casciola-Rosen L, Rosen A. Review: cancer-induced autoimmunity in the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(2):317–326.; with permission.

Additional studies are warranted to examine whether the mechanisms identified for RNA polymerase III apply more broadly to other subgroups with a high risk of cancer-associated scleroderma, such as patients with anti-RNPC3 antibodies.

Cancer protective immune responses may modify cancer risk in scleroderma

While the data suggesting a cancer-induced autoimmunity model in scleroderma patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies is compelling, it is striking that 80–85% of these patients remain cancer-free even over a prolonged period of follow-up. Could cancer be the initial trigger for scleroderma in patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies, with the subsequent anti-tumor response varying in its ability to eliminate the cancer or keep it in equilibrium without cancer emergence? Well-recognized features of the immune response include intra- and inter-molecular spreading. That many scleroderma antibody specificities target multi-component complexes, with multiple components being recognized by the antibody, is consistent with antigenic spreading. These features raised the question of whether targeting of additional autoantigens by the immune response could be cancer protective in anti-POLR3-positive scleroderma patients.

To investigate this, our group identified 168 individuals with scleroderma and anti-POLR3 antibodies (based on clinically available assays and confirmed by ELISA) with a roughly even mix of individuals with cancer or without cancer after at least five years of follow-up67. A comparison of the antibody profiles (generated by immunoprecipitation and visualized by fluorography) in these two subgroups showed clear enrichment of a 194 kDa protein targeted by antibodies in the cancer-negative group. This was subsequently identified as the catalytic subunit of RNA polymerase 1 (RPA194). When the full cohort was tested for antibodies against RPA194, anti-RPA194 was found to be significantly more common in the entire group without cancer (18.2%) compared to the group with cancer (3.8%), suggesting a potentially protective effect.

These findings raise the possibility that combinations of immune responses may have a previously unappreciated role in controlling cancer. They also highlight that knowledge of biomarkers that precisely define homogeneous disease subgroups will enable improved precision in cancer prediction in relevant subsets. For instance, while patients with anti-POLR3 antibodies have a significantly increased risk of cancer-associated scleroderma that warrants intensive cancer detection strategies, patients with both anti-POLR3 and anti-RPA194 may not require additional cancer screening at scleroderma onset.

Implications for cancer screening

Given compelling data suggesting a model of cancer-induced autoimmunity in subsets of scleroderma patients, important clinical questions arise. Do new onset scleroderma patients require intensive cancer detection strategies? If so, how do we direct the right cancer screening tests to the appropriate patients, such that we maximize detection while minimizing the harms (i.e. false positive results and costs) of over-screening? If cancer is detected and treated early, could this effectively treat scleroderma and improve outcomes? While there is not a strong evidence base to guide clinical decision making at this time, we share our current approach to cancer screening below.

Rheumatologists and primary care providers should ensure that all patients with scleroderma undergo comprehensive physical examination and age-, sex- and risk factor-based cancer screening tests according to recommendations for the general population68,69. Additional cancer screening studies may be considered based on the presence of scleroderma-specific risk factors. For example, patients with severe reflux that is refractory to standard proton pump inhibitor or H2 blocker therapy should be referred for upper endoscopy to evaluate for Barrett’s esophagus, and serial endoscopies may be required if there is evidence of dysplasia or severe erosive esophagitis70. Patients with a persistent globus sensation or unexplained dysphagia may need otolaryngology evaluation given the increased risk of head and neck cancers in scleroderma61,71. If cirrhosis has developed, for instance due to primary biliary cirrhosis overlap, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases has recommended cross-sectional imaging with or without alpha fetoprotein assessment at 6–12 month intervals72. Hematology referral may be warranted in the patient with new, unexplained cytopenias. There may be a role for serial chest computed tomography (CT) or low-dose chest CT monitoring for the development of lung cancer in scleroderma patients with ILD, but this requires further study. Exposure to immunosuppressive therapies may also be an important risk factor. Patients with prior cyclophosphamide exposure may benefit from annual urinalysis and urine cytology, whereas patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil should be advised to report any new or changing skin lesions. If there is a history of extensive sun exposure or prior skin cancers, serial full skin examinations to evaluate for atypical lesions should be considered.

While there are no published studies assessing cancer screening strategies in scleroderma, the data demonstrating an increased risk of cancer around the time of scleroderma onset in distinct autoantibody subsets raises the question of whether aggressive cancer detection strategies should be considered. In dermatomyositis, another rheumatic disease where a mechanism of cancer-induced autoimmunity has been postulated, aggressive cancer screening measures, including CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and whole body PET-CT, are often performed clinically. Whether a similar approach in high-risk scleroderma patients, such as those with anti-POLR3 antibodies or CTP-negative patients, would add value beyond traditional cancer screening tests requires further study. However, the data suggest that there may be a role for targeted cancer detection strategies based on autoantibody type and clinical phenotype61. For instance, anti-POLR3-positive patients with diffuse scleroderma have an increased risk of breast, prostate and tongue cancer, suggesting a role for mammography, PSA assessment and prostate examination, and otolaryngology examination in these patients. Similarly, anti-POLR3-positive patients with limited scleroderma have an increased risk of lung cancer, suggesting a role for chest CT examination. Additional studies are underway to define the optimal approach to cancer screening in these high-risk subsets that maximizes cancer detection while minimizing the harms of overscreening73.

Summary

The increased risk of cancer in scleroderma may be due to multiple mechanisms, with biologic data suggesting the development of cancer-induced autoimmunity in some patients. Recent epidemiologic studies indicate that autoantibody status and clinical phenotype may be useful filters to identify patient subgroups at high risk or low risk for cancer in scleroderma. Further work is needed to test the value of targeted cancer detection strategies in scleroderma, and to define whether early cancer detection and treatment improves scleroderma outcomes. It is also likely that careful investigation at the scleroderma-cancer interface may provide insight into mechanisms of naturally occurring anti-tumor immunity and development of autoimmunity in the rheumatic diseases.

KEY POINTS.

Scleroderma may be a paraneoplastic phenomenon in unique patient subgroups, including those with anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies or those who are negative for centromere, topoisomerase 1 or RNA polymerase III antibodies (CTP-negative).

All patients with new onset scleroderma should undergo comprehensive physical examination and age-, sex- and risk factor-based cancer screening tests.

Recent data suggest that autoantibody and cutaneous subtype may define cancer risk, type and timing in scleroderma. If validated, these findings may inform the development of targeted cancer screening guidelines.

Clinics Care Points.

Scleroderma may be a paraneoplastic phenomenon in unique patient subgroups, including those with anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies or those who are negative for centromere, topoisomerase 1 or RNA polymerase III antibodies (CTP-negative).

All patients with new onset scleroderma should undergo comprehensive physical examination and age-, sex- and risk factor-based cancer screening tests.

Recent data suggest that autoantibody and cutaneous subtype may define cancer risk, type and timing in scleroderma. If validated, these findings may inform the development of targeted cancer screening guidelines.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NIAMS (R01 AR073208) and the Donald B. and Dorothy L. Stabler Foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Disclose any relationship with a commercial company that has a direct financial interest in subject matter or materials discussed in article or with a company making a competing product. If nothing to disclose, please state “The Authors have nothing to disclose.”

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abu-Shakra M, Guillemin F, Lee P. Cancer in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1993;36(4):460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonifazi M, Tramacere I, Pomponio G, et al. Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) and cancer risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(1):143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derk CT, Rasheed M, Artlett CM, Jimenez SA. A cohort study of cancer incidence in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(6):1113–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto A, Arinuma Y, Nagai T, et al. Incidence and the risk factor of malignancy in Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis. Intern Med. 2012;51(13):1683–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill CL, Nguyen AM, Roder D, Roberts-Thomson P. Risk of cancer in patients with scleroderma: a population based cohort study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2003;62(8):728–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang KY, Yim HW, Kim IJ, et al. Incidence of cancer among patients with systemic sclerosis in Korea: results from a single centre. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009;38(4):299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo CF, Luo SF, Yu KH, et al. Cancer risk among patients with systemic sclerosis: a nationwide population study in Taiwan. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(1):44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olesen AB, Svaerke C, Farkas DK, Sørensen HT. Systemic sclerosis and the risk of cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(4):800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onishi A, Sugiyama D, Kumagai S, Morinobu A. Cancer incidence in systemic sclerosis: meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2013;65(7):1913–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenthal AK, McLaughlin JK, Linet MS, Persson I. Scleroderma and malignancy: an epidemiological study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1993;52(7):531–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal AK, McLaughlin JK, Gridley G, Nyrén O. Incidence of cancer among patients with systemic sclerosis. Cancer. 1995;76(5):910–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roumm AD, Medsger TA. Cancer and systemic sclerosis. An epidemiologic study. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1985;28(12):1336–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siau K, Laversuch CJ, Creamer P, O’Rourke KP. Malignancy in scleroderma patients from south west England: a population-based cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31(5):641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J-Q, Wan Y-N, Peng W-J, et al. The risk of cancer development in systemic sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan SC, Winkelmann RK. Cancer and scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115(8):950–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes AM, Woodrow JC, Verbov JL, Graham RM. Carcinoma of breast and scleroderma: four further cases and a literature review. Br J Rheumatol. 1989;28(1):65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Launay D, Le Berre R, Hatron P-Y, et al. Association between systemic sclerosis and breast cancer: eight new cases and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(6):516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee P, Alderdice C, Wilkinson S, Keystone EC, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD. Malignancy in progressive systemic sclerosis--association with breast carcinoma. J Rheumatol. 1983;10(4):665–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazzaroni M-G, Cavazzana I, Colombo E, et al. Malignancies in Patients with Anti-RNA Polymerase III Antibodies and Systemic Sclerosis: Analysis of the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Cohort and Possible Recommendations for Screening. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(5):639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moinzadeh P, Fonseca C, Hellmich M, et al. Association of anti-RNA polymerase III autoantibodies and cancer in scleroderma. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):R53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikpour M, Hissaria P, Byron J, et al. Prevalence, correlates and clinical usefulness of antibodies to RNA polymerase III in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional analysis of data from an Australian cohort. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(6):R211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah AA, Hummers LK, Casciola-Rosen L, Visvanathan K, Rosen A, Wigley FM. Examination of autoantibody status and clinical features associated with cancer risk and cancer-associated scleroderma. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ). 2015;67(4):1053–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pontifex EK, Hill CL, Roberts-Thomson P. Risk factors for lung cancer in patients with scleroderma: a nested case-control study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2007;66(4):551–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egiziano G, Bernatsky S, Shah AA. Cancer and autoimmunity: Harnessing longitudinal cohorts to probe the link. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30(1):53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trivedi PJ, Lammers WJ, van Buuren HR, et al. Stratification of hepatocellular carcinoma risk in primary biliary cirrhosis: a multicentre international study. Gut. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antonelli A, Ferri C, Ferrari SM, et al. Increased risk of papillary thyroid cancer in systemic sclerosis associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(3):480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters-Golden M, Wise RA, Hochberg M, Stevens MB, Wigley FM. Incidence of lung cancer in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1985;12(6):1136–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colaci M, Giuggioli D, Sebastiani M, et al. Lung cancer in scleroderma: results from an Italian rheumatologic center and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(3):374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faurschou M, Sorensen IJ, Mellemkjaer L, et al. Malignancies in Wegener’s granulomatosis: incidence and relation to cyclophosphamide therapy in a cohort of 293 patients. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(1):100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasifoglu T, Yasar Bilge S, Yildiz F, et al. Risk factors for malignancy in systemic sclerosis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(6):1529–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monach PA, Arnold LM, Merkel PA. Incidence and prevention of bladder toxicity from cyclophosphamide in the treatment of rheumatic diseases: a data-driven review. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2010;62(1):9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernatsky S, Ramsey-Goldman R, Joseph L, et al. Lymphoma risk in systemic lupus: effects of disease activity versus treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):138–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreyer L, Faurschou M, Mogensen M, Jacobsen S. High incidence of potentially virus-induced malignancies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a long-term followup study in a Danish cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3032–3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bichari W, Bartiromo M, Mohey H, et al. Significant risk factors for occurrence of cancer after renal transplantation: a single center cohort study of 1265 cases. Transplantation proceedings. 2009;41(2):672–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brewer JD, Colegio OR, Phillips PK, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for skin cancer after heart transplant. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(12):1391–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mareen R, Galeano C, Fernandez-Rodriguez A, et al. Effects of the new immunosuppressive agents on the occurrence of malignancies after renal transplantation. Transplantation proceedings. 2010;42(8):3055–3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang K, Zhang H, Li Y, et al. Safety of mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine in renal transplantation: a systematic review. Transplantation proceedings. 2004;36(7):2068–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crane GM, Powell H, Kostadinov R, et al. Primary CNS lymphoproliferative disease, mycophenolate and calcineurin inhibitor usage. Oncotarget. 2015;6(32):33849–33866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cappelli LC, Shah AA. The relationships between cancer and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020. February 3:101472. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2019.101472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Picano E, Semelka R, Ravenel J, Matucci-Cerinic M. Rheumatological diseases and cancer: the hidden variable of radiation exposure. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(12):2065–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berger CC, Bokemeyer C, Schneider M, Kuczyk MA, Schmoll HJ. Secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon and other late vascular complications following chemotherapy for testicular cancer. European journal of cancer. 1995;31A(13–14):2229–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bessis D, Guillot B, Legouffe E, Guilhou JJ. Gemcitabine-associated scleroderma-like changes of the lower extremities. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004;51(2 Suppl):S73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clowse ME, Wigley FM. Digital necrosis related to carboplatin and gemcitabine therapy in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(6):1341–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen IS, Mosher MB, O’Keefe EJ, Klaus SN, De Conti RC. Cutaneous toxicity of bleomycin therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107(4):553–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Angelis R, Bugatti L, Cerioni A, Del Medico P, Filosa G. Diffuse scleroderma occurring after the use of paclitaxel for ovarian cancer. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(1):49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finch WR, Rodnan GP, Buckingham RB, Prince RK, Winkelstein A. Bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Rheumatol. 1980;7(5):651–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colver GB, Rodger A, Mortimer PS, Savin JA, Neill SM, Hunter JA. Post-irradiation morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120(6):831–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shah DJ, Hirpara R, Poelman CL, et al. Impact of Radiation Therapy on Scleroderma and Cancer Outcomes in Scleroderma Patients With Breast Cancer. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(10):1517–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varga J, Haustein UF, Creech RH, Dwyer JP, Jimenez SA. Exaggerated radiation-induced fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Jama. 1991;265(24):3292–3295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, Shenoy NK, Markovic SN, Thanarajasingam U. Scleroderma Induced by Pembrolizumab: A Case Series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(7):1158–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suárez-Díaz S, Coto-Hernández R, Yllera-Gutiérrez C, Álvarez-Fernández C, Trapiella-Martínez L, Caminal-Montero L. Scleroderma-like syndrome associated with pembrolizumab. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2020. 10.1177/2397198320905192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tjarks BJ, Kerkvliet AM, Jassim AD, Bleeker JS. Scleroderma-like skin changes induced by checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45(8):615–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cho M, Nonomura Y, Kaku Y, et al. Scleroderma-like syndrome associated with nivolumab treatment in malignant melanoma. J Dermatol. 2019;46(1):e43–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hasegawa M, Sato S, Sakai H, Ohashi T, Takehara K. Systemic sclerosis revealing T-cell lymphoma. Dermatology (Basel). 1999;198(1):75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juarez M, Marshall R, Denton C, Evely R. Paraneoplastic scleroderma secondary to hairy cell leukaemia successfully treated with cladribine. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(11):1734–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruni C, Lages A, Patel H, et al. Resolution of paraneoplastic PM/Scl-positive systemic sclerosis after curative resection of a pancreatic tumour. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(2):317–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah AA, Rosen A, Hummers L, Wigley F, Casciola-Rosen L. Close temporal relationship between onset of cancer and scleroderma in patients with RNA polymerase I/III antibodies. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2010;62(9):2787–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Airo P, Ceribelli A, Cavazzana I, Taraborelli M, Zingarelli S, Franceschini F. Malignancies in Italian patients with systemic sclerosis positive for anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saigusa R, Asano Y, Nakamura K, et al. Association of anti-RNA polymerase III antibody and malignancy in Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis. J Dermatol. 2015;42(5):524–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Igusa T, Hummers LK, Visvanathan K, et al. Autoantibodies and scleroderma phenotype define subgroups at high-risk and low-risk for cancer. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(8):1179–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu GJ, Shah AA, Li MZ, et al. Systematic autoantigen analysis identifies a distinct subtype of scleroderma with coincident cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(47):E7526–E7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shah AA, Xu G, Rosen A, et al. Brief Report: Anti-RNPC-3 Antibodies As a Marker of Cancer-Associated Scleroderma. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ). 2017;69(6):1306–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shah AA, Rosen A, Hummers LK, et al. Evaluation of cancer-associated myositis and scleroderma autoantibodies in breast cancer patients without rheumatic disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35 Suppl 106(4):71–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joseph CG, Darrah E, Shah AA, et al. Association of the autoimmune disease scleroderma with an immunologic response to cancer. Science. 2014;343(6167):152–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shah AA, Casciola-Rosen L, Rosen A. Review: cancer-induced autoimmunity in the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(2):317–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shah AA, Laiho M, Rosen A, Casciola-Rosen L. Protective Effect Against Cancer of Antibodies to the Large Subunits of Both RNA Polymerases I and III in Scleroderma. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ). 2019;71(9):1571–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shah AA, Casciola-Rosen L. Cancer and scleroderma: a paraneoplastic disease with implications for malignancy screening. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27(6):563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shah AA, Kuwana M. Cancer in Systemic Sclerosis In: Varga J, Denton CP, Wigley FM, Allanore Y, Kuwana M, eds. Scleroderma: From Pathogenesis to Comprehensive Management. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2016:525–532. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shaheen NJ, Weinberg DS, Denberg TD, et al. Upper endoscopy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2012;157(11):808–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Derk CT, Rasheed M, Spiegel JR, Jimenez SA. Increased incidence of carcinoma of the tongue in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(4):637–641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50(1):291–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shah AA, Casciola-Rosen L. Mechanistic and clinical insights at the scleroderma-cancer interface. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2017;2(3):153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]