Abstract

The tangent Graeffe method has been developed for the efficient computation of single roots of polynomials over finite fields with multiplicative groups of smooth order. It is a key ingredient of sparse interpolation using geometric progressions, in the case when blackbox evaluations are comparatively cheap. In this paper, we improve the complexity of the method by a constant factor and we report on a new implementation of the method and a first parallel implementation.

Introduction

Consider a polynomial function  over a field

over a field  given through a black box capable of evaluating f at points in

given through a black box capable of evaluating f at points in  . The problem of sparse interpolation is to recover the representation of

. The problem of sparse interpolation is to recover the representation of  in its usual form, as a linear combination

in its usual form, as a linear combination

|

1 |

of monomials  . One popular approach to sparse interpolation is to evaluate f at points in a geometric progression. This approach goes back to work of Prony in the eighteen’s century [15] and became well known after Ben-Or and Tiwari’s seminal paper [2]. It has widely been used in computer algebra, both in theory and in practice; see [16] for a nice survey.

. One popular approach to sparse interpolation is to evaluate f at points in a geometric progression. This approach goes back to work of Prony in the eighteen’s century [15] and became well known after Ben-Or and Tiwari’s seminal paper [2]. It has widely been used in computer algebra, both in theory and in practice; see [16] for a nice survey.

More precisely, if a bound T for the number of terms t is known, then we first evaluate f at  pairwise distinct points

pairwise distinct points  , where

, where  and

and  for all

for all  . The generating function of the evaluations at

. The generating function of the evaluations at  satisfies the identity

satisfies the identity

|

where  and

and  is of degree

is of degree  . The rational function

. The rational function  can be recovered from

can be recovered from  using fast Padé approximation [4]. For well chosen points

using fast Padé approximation [4]. For well chosen points  , it is often possible to recover the exponents

, it is often possible to recover the exponents  from the values

from the values  . If the exponents

. If the exponents  are known, then the coefficients

are known, then the coefficients  can also be recovered using fast structured linear algebra [5]. This leaves us with the question how to compute the roots

can also be recovered using fast structured linear algebra [5]. This leaves us with the question how to compute the roots  of

of  in an efficient way.

in an efficient way.

For practical applications in computer algebra, we usually have  , in which case it is most efficient to use a multi-modular strategy, and reduce to coefficients in a finite field

, in which case it is most efficient to use a multi-modular strategy, and reduce to coefficients in a finite field  , where p is a prime number that we are free to choose. It is well known that polynomial arithmetic over

, where p is a prime number that we are free to choose. It is well known that polynomial arithmetic over  can be implemented most efficiently using FFTs when the order

can be implemented most efficiently using FFTs when the order  of the multiplicative group is smooth. In practice, this prompts us to choose p of the form

of the multiplicative group is smooth. In practice, this prompts us to choose p of the form  for some small s and such that p fits into a machine word.

for some small s and such that p fits into a machine word.

The traditional way to compute roots of polynomials over finite fields is using Cantor and Zassenhaus’ method [6]. In [10, 11], alternative algorithms were proposed for our case of interest when  is smooth. The fastest algorithm was based on the tangent Graeffe transform and it gains a factor

is smooth. The fastest algorithm was based on the tangent Graeffe transform and it gains a factor  with respect to Cantor–Zassenhaus’ method. The aim of the present paper is to report on a parallel implementation of this new algorithm and on a few improvements that allow for a further constant speed-up.

with respect to Cantor–Zassenhaus’ method. The aim of the present paper is to report on a parallel implementation of this new algorithm and on a few improvements that allow for a further constant speed-up.

In Sect. 2, we recall the Graeffe transform and the heuristic root finding method based on the tangent Graeffe transform from [10]. In Sect. 3, we present the main new theoretical improvements, which all rely on optimizations in the FFT-model for fast polynomial arithmetic. Our contributions are twofold. In the FFT-model, one backward transform out of four can be saved for Graeffe transforms of order two (see Sect. 3.2). When composing a large number of Graeffe transforms of order two, FFT caching can be used to gain another factor of 3/2 (see Sect. 3.3). In the longer preprint version of the paper [12], we also show how to generalize our methods to Graeffe transforms of general orders and how to use it in combination with the truncated Fourier transform.

Section 4 is devoted to our new sequential and parallel implementations of the algorithm in C and Cilk C. Our sequential implementation confirms the gain of a new factor of two when using the new optimizations. So far, we have achieved a parallel speed-up by a factor of 4.6 on an 8-core machine. Our implementation is freely available at http://www.cecm.sfu.ca/CAG/code/TangentGraeffe.

Root Finding Using the Tangent Graeffe Transform

Graeffe Transforms

The traditional Graeffe transform of a monic polynomial  of degree d is the unique monic polynomial

of degree d is the unique monic polynomial  of degree d such that

of degree d such that

|

2 |

If P splits over  into linear factors

into linear factors  , then one has

, then one has

|

More generally, given  , we define the Graeffe transform of order r to be the unique monic polynomial

, we define the Graeffe transform of order r to be the unique monic polynomial  of degree d such that

of degree d such that  . If

. If  , then

, then

|

If  , then we have

, then we have

|

3 |

Root Finding Using Tangent Graeffe Transforms

Let  be a formal indeterminate with

be a formal indeterminate with  . Elements in

. Elements in  are called tangent numbers. Now let

are called tangent numbers. Now let  be of the form

be of the form  where

where  are pairwise distinct. Then the tangent deformation

are pairwise distinct. Then the tangent deformation

satisfies

satisfies

|

The definitions from the previous subsection readily extend to coefficients in  instead of

instead of  . Given

. Given  , we call

, we call  the tangent Graeffe transform of P of order r. We have

the tangent Graeffe transform of P of order r. We have

|

where

|

Now assume that we have an efficient way to determine the roots  of

of  . For some polynomial

. For some polynomial  , we may decompose

, we may decompose  For any root

For any root  of

of  , we then have

, we then have

|

Whenever  happens to be a single root of

happens to be a single root of  , it follows that

, it follows that

|

If  , this finally allows us to recover

, this finally allows us to recover  as

as  .

.

Heuristic Root Finding over Smooth Finite Fields

Assume now that  is a finite field, where p is a prime number of the form

is a finite field, where p is a prime number of the form  for some small

for some small  . Assume also that

. Assume also that  be a primitive element of order

be a primitive element of order  for the multiplicative group of

for the multiplicative group of  .

.

Let  be as in the previous subsection. The tangent Graeffe method can be used to efficiently compute those

be as in the previous subsection. The tangent Graeffe method can be used to efficiently compute those  of P for which

of P for which  is a single root of

is a single root of  . In order to guarantee that there are a sufficient number of such roots, we first replace P(z) by

. In order to guarantee that there are a sufficient number of such roots, we first replace P(z) by  for a random shift

for a random shift  , and use the following heuristic:

, and use the following heuristic:

H For any subset

of cardinality d and any

of cardinality d and any  , there exist at least p/2 elements

, there exist at least p/2 elements  such that

such that  contains at least 2d/3 elements.

contains at least 2d/3 elements.

For a random shift  and any

and any  , the assumption ensures with probability at least 1/2 that

, the assumption ensures with probability at least 1/2 that  has at least d/3 single roots.

has at least d/3 single roots.

Now take r to be the largest power of two such that  and let

and let  . By construction, note that

. By construction, note that  . The roots

. The roots  of

of  are all s-th roots of unity in the set

are all s-th roots of unity in the set  . We may thus determine them by evaluating

. We may thus determine them by evaluating  at

at  for

for  . Since

. Since  , this can be done efficiently using a discrete Fourier transform. Combined with the tangent Graeffe method from the previous subsection, this leads to the following probabilistic algorithm for root finding:

, this can be done efficiently using a discrete Fourier transform. Combined with the tangent Graeffe method from the previous subsection, this leads to the following probabilistic algorithm for root finding:

Remark 1

To compute  we may use

we may use  , which requires three polynomial multiplications in

, which requires three polynomial multiplications in  of degree d. In total, step 5 thus performs

of degree d. In total, step 5 thus performs  such multiplications. We discuss how to perform step 5 efficiently in the FFT model in Sect. 3.

such multiplications. We discuss how to perform step 5 efficiently in the FFT model in Sect. 3.

Remark 2

For practical implementations, one may vary the threshold  for r and the resulting threshold

for r and the resulting threshold  for s. For larger values of s, the computations of the DFTs in step 6 get more expensive, but the proportion of single roots goes up, so more roots are determined at each iteration. From an asymptotic complexity perspective, it would be best to take

for s. For larger values of s, the computations of the DFTs in step 6 get more expensive, but the proportion of single roots goes up, so more roots are determined at each iteration. From an asymptotic complexity perspective, it would be best to take  . In practice, we actually preferred to take the lower threshold

. In practice, we actually preferred to take the lower threshold  , because the constant factor of our implementation of step 6 (based on Bluestein’s algorithm [3]) is significant with respect to our highly optimized implementation of the tangent Graeffe method. A second reason we prefer s of size O(d) instead of

, because the constant factor of our implementation of step 6 (based on Bluestein’s algorithm [3]) is significant with respect to our highly optimized implementation of the tangent Graeffe method. A second reason we prefer s of size O(d) instead of  is that the total space used by the algorithm is linear in s. In the future, it would be interesting to further speed up step 6 by investing more time in the implementation of high performance DFTs of general orders s.

is that the total space used by the algorithm is linear in s. In the future, it would be interesting to further speed up step 6 by investing more time in the implementation of high performance DFTs of general orders s.

Computing Graeffe Transforms

Reminders About Discrete Fourier Transforms

Assume  is invertible in

is invertible in  and let

and let  be a primitive n-th root of unity. Consider a polynomial

be a primitive n-th root of unity. Consider a polynomial  . Then the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of order n of the sequence

. Then the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of order n of the sequence  is defined by

is defined by

|

We will write  for the cost of one discrete Fourier transform in terms of the number of operations in

for the cost of one discrete Fourier transform in terms of the number of operations in  and assume that

and assume that  . For any

. For any  , we have

, we have

|

4 |

If n is invertible in  , then it follows that

, then it follows that  . The costs of direct and inverse transforms therefore coincide up to a factor O(n).

. The costs of direct and inverse transforms therefore coincide up to a factor O(n).

If  is composite,

is composite,  , and

, and  , then it is well known [7] that

, then it is well known [7] that

|

5 |

This means that a DFT of length n reduces to  transforms of length

transforms of length  plus

plus  transforms of length

transforms of length  plus n multiplications in

plus n multiplications in  :

:

|

In particular, if  , then

, then  .

.

It is sometimes convenient to apply DFTs directly to polynomials as well; for this reason, we also define  . Given two polynomials

. Given two polynomials  with

with  , we may then compute the product AB using

, we may then compute the product AB using

|

In particular, if  denotes the cost of multiplying two polynomials of degree

denotes the cost of multiplying two polynomials of degree  , then we obtain

, then we obtain  .

.

Remark 3

In Algorithm 1, we note that step 6 comes down to the computation of three DFTs of length s. Since r is a power of two, this length is of the form  for some

for some  . In view of (5), we may therefore reduce step 6 to

. In view of (5), we may therefore reduce step 6 to  DFTs of length

DFTs of length  plus

plus  DFTs of length

DFTs of length  . If

. If  is very small, then we may use a naive implementation for DFTs of length

is very small, then we may use a naive implementation for DFTs of length  . In general, one may use Bluestein’s algorithm [3] to reduce the computation of a DFT of length

. In general, one may use Bluestein’s algorithm [3] to reduce the computation of a DFT of length  into the computation of a product in

into the computation of a product in  , which can in turn be computed using FFT-multiplication and three DFTs of length a larger power of two.

, which can in turn be computed using FFT-multiplication and three DFTs of length a larger power of two.

Graeffe Transforms of Order Two

Let  be a field with a primitive (2n)-th root of unity

be a field with a primitive (2n)-th root of unity  . Let

. Let  be a polynomial of degree

be a polynomial of degree  . Then the relation (2) yields

. Then the relation (2) yields

|

6 |

For any  , we further note that

, we further note that

|

7 |

so  can be obtained from

can be obtained from  using n transpositions of elements in

using n transpositions of elements in  . Concerning the inverse transform, we also note that

. Concerning the inverse transform, we also note that

|

for  . Plugging this into (6), we conclude that

. Plugging this into (6), we conclude that

|

This leads to the following algorithm for the computation of G(P):

Proposition 1

Let  be a primitive 2n-th root of unity in

be a primitive 2n-th root of unity in  and assume that 2 is invertible in

and assume that 2 is invertible in  . Given a monic polynomial

. Given a monic polynomial  with

with  , we can compute G(P) in time

, we can compute G(P) in time  .

.

Proof

We have already explained the correctness of Algorithm 2. Step 1 requires one forward DFT of length 2n and cost  . Step 2 can be done in O(n). Step 3 requires one inverse DFT of length n and cost

. Step 2 can be done in O(n). Step 3 requires one inverse DFT of length n and cost  . The total cost of Algorithm 2 is therefore

. The total cost of Algorithm 2 is therefore  .

.

Remark 4

In terms of the complexity of multiplication, we obtain  . This gives a

. This gives a  improvement over the previously best known bound

improvement over the previously best known bound  that was used in [10]. Note that the best known algorithm for squaring polynomials of degree

that was used in [10]. Note that the best known algorithm for squaring polynomials of degree  is

is  . It would be interesting to know whether squares can also be computed in time

. It would be interesting to know whether squares can also be computed in time  .

.

Graeffe Transforms of Power of Two Orders

In view of (3), Graeffe transforms of power of two orders  can be computed using

can be computed using

|

8 |

Now assume that we computed the first Graeffe transform G(P) using Algorithm 2 and that we wish to apply a second Graeffe transform to the result. Then we note that

|

9 |

is already known for  . We can use this to accelerate step 1 of the second application of Algorithm 2. Indeed, in view of (5) for

. We can use this to accelerate step 1 of the second application of Algorithm 2. Indeed, in view of (5) for  and

and  , we have

, we have

|

10 |

for  . In order to exploit this idea in a recursive fashion, it is useful to modify Algorithm 2 so as to include

. In order to exploit this idea in a recursive fashion, it is useful to modify Algorithm 2 so as to include  in the input and

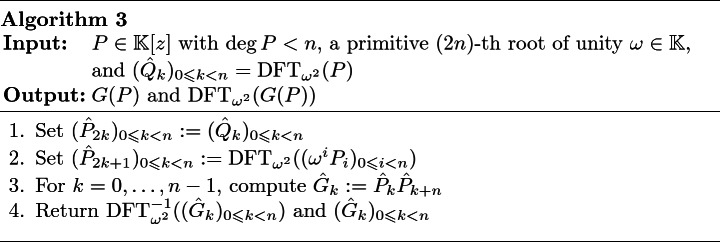

in the input and  in the output. This leads to the following algorithm:

in the output. This leads to the following algorithm:

Proposition 2

Let  be a primitive 2n-th root of unity in

be a primitive 2n-th root of unity in  and assume that 2 is invertible in

and assume that 2 is invertible in  . Given a monic polynomial

. Given a monic polynomial  with

with  and

and  , we can compute

, we can compute  in time

in time  .

.

Proof

It suffices to compute  and then to apply Algorithm 3 recursively, m times. Every application of Algorithm 3 now takes

and then to apply Algorithm 3 recursively, m times. Every application of Algorithm 3 now takes  operations in

operations in  , whence the claimed complexity bound.

, whence the claimed complexity bound.

Remark 5

In [10], Graeffe transforms of order  were directly computed using the formula (8), using

were directly computed using the formula (8), using  operations in

operations in  , which is twice as slow as the new algorithm.

, which is twice as slow as the new algorithm.

Implementation and Benchmarks

We have implemented the tangent Graeffe root finding algorithm (Algorithm 1) in C with the optimizations presented in Sect. 3. Our C implementation supports primes of size up to 63 bits. In what follows all complexities count arithmetic operations in  .

.

In Tables 1 and 2 the input polynomial P(z) of degree d is constructed by choosing d distinct values  for

for  at random and creating

at random and creating  . We will use

. We will use  , a smooth 63 bit prime. For this prime

, a smooth 63 bit prime. For this prime  is

is  .

.

Table 1.

Sequential timings in CPU seconds for  and using

and using  .

.

| d | Our sequential TG implementation in C | Magma CZ timings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | First | %roots | Step 5 | Step 6 | Step 9 | V2.25-3 | V2.25-5 | |

|

0.11 s | 0.07 s | 69.8% | 0.04 s | 0.02 s | 0.01 s | 23.22 s | 8.43 |

|

0.22 s | 0.14 s | 69.8% | 0.09 s | 0.03 s | 0.01 s | 56.58 s | 18.94 |

|

0.48 s | 0.31 s | 68.8% | 0.18 s | 0.07 s | 0.02 s | 140.76 s | 44.07 |

|

1.00 s | 0.64 s | 69.2% | 0.38 s | 0.16 s | 0.04 s | 372.22 s | 103.5 |

|

2.11 s | 1.36 s | 68.9% | 0.78 s | 0.35 s | 0.10 s | 1494.0 s | 234.2 |

|

4.40 s | 2.85 s | 69.2% | 1.62 s | 0.74 s | 0.23 s | 6108.8 s | 534.5 |

|

9.16 s | 5.91 s | 69.2% | 3.33 s | 1.53 s | 0.51 s | NA | 1219 |

|

19.2 s | 12.4 s | 69.2% | 6.86 s | 3.25 s | 1.13 s | NA | 2809 |

Table 2.

Real times in seconds for 1 core (8 cores) and  .

.

| d | Our parallel tangent Graeffe implementation in Cilk C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | First | Step 5 | Step 6 | Step 9 | |

|

18.30 s(9.616 s) | 11.98 s(2.938 s) | 6.64 s(1.56 s) | 3.13 s(0.49 s) | 1.09 s(0.29 s) |

|

38.69 s(12.40 s) | 25.02 s(5.638 s) | 13.7 s(3.03 s) | 6.62 s(1.04 s) | 2.40 s(0.36 s) |

|

79.63 s(20.16 s) | 52.00 s(11.52 s) | 28.1 s(5.99 s) | 13.9 s(2.15 s) | 5.32 s(0.85 s) |

|

166.9 s(41.62 s) | 107.8 s(23.25 s) | 57.6 s(11.8 s) | 28.9 s(4.57 s) | 11.7 s(1.71 s) |

|

346.0 s(76.64 s) | 223.4 s(46.94 s) | 117 s(23.2 s) | 60.3 s(9.45 s) | 25.6 s(3.54 s) |

|

712.7 s(155.0 s) | 459.8 s(95.93 s) | 238 s(46.7 s) | 125 s(19.17) | 55.8 s(7.88 s) |

|

1465 s(307.7 s) | 945.0 s(194.6 s) | 481 s(92.9 s) | 259 s(39.2 s) | 121 s(16.9 s) |

One goal we have is to determine how much faster the Tangent Graeffe (TG) root finding algorithm is in practice when compared with the Cantor-Zassenhaus (CZ) algorithm which is implemented in many computer algebra systems. In Table 1 we present timings comparing our sequential implementation of the TG algorithm with Magma’s implementation of the CZ algorithm. For polynomials in  , Magma uses Shoup’s factorization algorithm from [17]. For our input P(z), with d distinct linear factors, Shoup uses the Cantor–Zassenhaus equal degree factorization method. The average complexity of TG is

, Magma uses Shoup’s factorization algorithm from [17]. For our input P(z), with d distinct linear factors, Shoup uses the Cantor–Zassenhaus equal degree factorization method. The average complexity of TG is  and of CZ is

and of CZ is  .

.

The timings in Table 1 are sequential timings obtained on a Linux server with an Intel Xeon E5-2660 CPU with 8 cores. In Table 1 the time in column “first” is for the first application of the TG algorithm (steps 1–9 of Algorithm 1), which obtains about 69% of the roots. The time in column “total” is the total time for the TG algorithm. Columns step 5, step 6, and step 9 report the time spent in steps 5, 6, and 9 in Algorithm 1 and do not count time in the recursive call in step 10.

The Magma timings are for Magma’s +Factorization+ command. The timings for Magma version V2.25-3 suggest that Magma’s CZ implementation involves a subalgorithm with quadratic asymptotic complexity. Indeed it turns out that the author of the code implemented all of the sub-quadratic polynomial arithmetic correctly, as demonstrated by the second set of timings for Magma in column V2.25-5, but inserted the d linear factors found into a list using linear insertion! Allan Steel of the Magma group identified and fixed the offending subroutine for Magma version V2.25-5. The timings show that TG is faster than CZ by a factor of 76.6 (=8.43/0.11) to 146.3 (=2809/19.2).

We also wanted to attempt a parallel implementation. To do this we used the MIT Cilk C compiler from [8]. Cilk provides a simple fork-join model of parallelism. Unlike the CZ algorithm, TG has no gcd computations that are hard to parallelize. We present some initial parallel timing data in Table 2. The timings in parentheses are parallel timings for 8 cores.

Implementation Notes

To implement the Taylor shift  in step 3, we used the

in step 3, we used the  method from [1, Lemma 3]. For step 5 we use Algorithm 3. It has complexity

method from [1, Lemma 3]. For step 5 we use Algorithm 3. It has complexity  . To evaluate

. To evaluate  and B(z) in step 6 in

and B(z) in step 6 in  we used the Bluestein transformation [3]. In step 9 to compute the product

we used the Bluestein transformation [3]. In step 9 to compute the product  , for

, for  roots, we used the

roots, we used the  product tree multiplication algorithm [9]. The division in step 10 is done in

product tree multiplication algorithm [9]. The division in step 10 is done in  with the fast division.

with the fast division.

The sequential timings in Tables 1 and 2 show that steps 5, 6 and 9 account for about 90% of the total time. We parallelized these three steps as follows. For step 5, the two forward and two inverse FFTs are done in parallel. We also parallelized our radix 2 FFT by parallelizing recursive calls for size  and the main loop in blocks of size

and the main loop in blocks of size  as done in [14]. For step 6 there are three applications of Bluestein to compute

as done in [14]. For step 6 there are three applications of Bluestein to compute  ,

,  and

and  . We parallelized these (thereby doubling the overall space used by our implementation). The main computation in the Bluestein transformation is a polynomial multiplication of two polynomials of degree s. The two forward FFTs are done in parallel and the FFTs themselves are parallelized as for step 5. For the product in step 9 we parallelize the two recursive calls in the tree multiplication for large sizes and again, the FFTs are parallelized as for step 5.

. We parallelized these (thereby doubling the overall space used by our implementation). The main computation in the Bluestein transformation is a polynomial multiplication of two polynomials of degree s. The two forward FFTs are done in parallel and the FFTs themselves are parallelized as for step 5. For the product in step 9 we parallelize the two recursive calls in the tree multiplication for large sizes and again, the FFTs are parallelized as for step 5.

To improve parallel speedup we also parallelized the polynomial multiplication in step 3 and the computation of the roots in step 8. Although step 8 is O(|S|), it is relatively expensive because of two inverse computations in  . Because we have not parallelized about 5% of the computation the maximum parallel speedup we can obtain is a factor of

. Because we have not parallelized about 5% of the computation the maximum parallel speedup we can obtain is a factor of  . The best overall parallel speedup we obtained is a factor of 4.6 = 1465/307.7 for

. The best overall parallel speedup we obtained is a factor of 4.6 = 1465/307.7 for  .

.

Footnotes

Note: This paper received funding from NSERC (Canada) and “Agence de l’innovation de défense” (France).

Note: This document has been written using GNU

[13].

[13].

Contributor Information

Anna Maria Bigatti, Email: bigatti@dima.unige.it.

Jacques Carette, Email: carette@mcmaster.ca.

James H. Davenport, Email: j.h.davenport@bath.ac.uk

Michael Joswig, Email: joswig@math.tu-berlin.de.

Timo de Wolff, Email: t.de-wolff@tu-braunschweig.de.

Michael Monagan, Email: mmonagan@sfu.ca.

References

- 1.Aho AV, Steiglitz K, Ullman JD. Evaluating polynomials on a fixed set of points. SIAM J. Comput. 1975;4:533–539. doi: 10.1137/0204045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Or, M., Tiwari, P.: A deterministic algorithm for sparse multivariate polynomial interpolation. In: STOC 1988: Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, pp. 301–309. ACM Press (1988)

- 3.Bluestein LI. A linear filtering approach to the computation of discrete Fourier transform. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 1970;18(4):451–455. doi: 10.1109/TAU.1970.1162132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent RP, Gustavson FG, Yun DYY. Fast solution of Toeplitz systems of equations and computation of Padé approximants. J. Algorithms. 1980;1(3):259–295. doi: 10.1016/0196-6774(80)90013-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canny, J., Kaltofen, E., Lakshman, Y.: Solving systems of non-linear polynomial equations faster. In: Proceedings of the ACM-SIGSAM 1989 International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation, pp. 121–128. ACM Press (1989)

- 6.Cantor DG, Zassenhaus H. A new algorithm for factoring polynomials over finite fields. Math. Comput. 1981;36(154):587–592. doi: 10.1090/S0025-5718-1981-0606517-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooley JW, Tukey JW. An algorithm for the machine calculation of complex Fourier series. Math. Comput. 1965;19:297–301. doi: 10.1090/S0025-5718-1965-0178586-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frigo, M., Leisorson, C.E., Randall, R.K.: The implementation of the Cilk-5 multithreaded language. In: Proceedings of PLDI 1998, pp. 212–223. ACM (1998)

- 9.von zur Gathen, J., Gerhard, J.: Modern Computer Algebra, 3rd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York (2013)

- 10.Grenet, B., van der Hoeven, J., Lecerf, G.: Randomized root finding over finite fields using tangent Graeffe transforms. In: Proceedings of the ISSAC 2015, pp. 197–204. ACM, New York (2015)

- 11.Grenet B, van der Hoeven J, Lecerf G. Deterministic root finding over finite fields using Graeffe transforms. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput. 2015;27(3):237–257. doi: 10.1007/s00200-015-0280-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Hoeven, J., Monagan, M.: Implementing the tangent Graeffe root finding method. Technical report, HAL (2020). http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02525408

- 13.van der Hoeven, J., et al.: GNU TeXmacs (1998). http://www.texmacs.org

- 14.Law, M., Monagan, M.: A parallel implementation for polynomial multiplication modulo a prime. In: Proceedings of PASCO 2015, pp. 78–86. ACM (2015)

- 15.Prony, R.: Essai expérimental et analytique sur les lois de la dilatabilité des fluides élastiques et sur celles de la force expansive de la vapeur de l’eau et de la vapeur de l’alkool, à différentes températures. J. de l’École Polytechnique Floréal et Plairial, an III 1(cahier 22), 24–76 (1795)

- 16.Roche, D.S.: What can (and can’t) we do with sparse polynomials? In: Arreche, C. (ed.) ISSAC 2018: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation, pp. 25–30. ACM Press (2018)

- 17.Shoup V. A new polynomial factorization and its implementation. J. Symb. Comput. 1995;20(4):363–397. doi: 10.1006/jsco.1995.1055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]