Abstract

Background:

Bereavement support is a key component of palliative care, with different types of support recommended according to need. Previous reviews have typically focused on specialised interventions and have not considered more generic forms of support, drawing on different research methodologies.

Aim:

To review the quantitative and qualitative evidence on the effectiveness and impact of interventions and services providing support for adults bereaved through advanced illness.

Design:

A mixed-methods systematic review was conducted, with narrative synthesis of quantitative results and thematic synthesis of qualitative results. The review protocol is published in PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero, CRD42016043530).

Data sources:

The databases MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Social Policy and Practice were searched from 1990 to March 2019. Studies were included which reported evaluation results of bereavement interventions, following screening by two independent researchers. Study quality was assessed using GATE checklists.

Results:

A total of 31 studies were included, reporting on bereavement support groups, psychological and counselling interventions and a mix of other forms of support. Improvements in study outcomes were commonly reported, but the quality of the quantitative evidence was generally poor or mixed. Three main impacts were identified in the qualitative evidence, which also varied in quality: ‘loss and grief resolution’, ‘sense of mastery and moving ahead’ and ‘social support’.

Conclusion:

Conclusions on effectiveness are limited by small sample sizes and heterogeneity in study populations, models of care and outcomes. The qualitative evidence suggests several cross-cutting benefits and helps explain the impact mechanisms and contextual factors that are integral to the support.

Keywords: Palliative care, systematic review, bereavement, grief

What is already known about the topic?

The support needs of people experiencing bereavement vary significantly.

Bereavement support in palliative care involves different types and levels of provision to accommodate these needs.

Specialist grief therapy is known to be effective for those with high-level risk and needs.

What this paper adds?

Bereavement interventions were wide ranging and included bereavement support and social groups, psychological and counselling interventions and other types of support such as arts-based, befriending and relaxation interventions.

Good quality randomised controlled trial evidence was only available for targeted family therapy and a non-targeted group–based therapy intervention, both of which were introduced during the caregiving period and found to be partially effective.

The synthesis of qualitative evidence identified three core impacts which were common across interventions: ‘loss and grief resolution’, ‘sense of mastery and moving ahead’ and ‘social support’.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

The qualitative evidence suggests the value of peer support alongside opportunities for reflection, emotional expression and restoration-focused activities for those with moderate-level needs.

These findings suggest the relevance of resilience and public health–based approaches to bereavement care.

Background

Grieving is a natural process, in which most people learn to adjust without a need for formal support.1,2 However, the relationship between grief and poor mental and physical health is well established.3,4 It is estimated that between 6% and 20% of adults experiencing a loss develop complicated grief symptoms,2,5–7 which have been described as painful and persistent reactions associated with impaired psychological, social and daily functioning.6,8,9 Estimates of complicated grief in bereaved caregivers also vary, with between 8% and 30% prevalence reported.9,10

Palliative care has an important role to play in supporting caregivers and families of patients’ with advanced disease,11–14 with recommendations that their bereavement needs are assessed and addressed with appropriate psychosocial supports.12,13 NICE recommends a three-component model which recognises different levels and type of support,13 and which maps closely to wider calls for a need-based three-tiered public health approach:1,13

Component 1 (universal) where information is offered regarding the experience of bereavement and locally available support. Support is based within informal social networks, including family and friends.

Component 2 (selective) which makes provision for people with moderate needs to reflect upon their grief through counselling and other forms of support. Support may be provided individually or in a group environment.

Component 3 (indicated) which encompasses specialist interventions for those with complex needs and at high risk of prolonged grief disorder (PGD), including specialist counselling and mental health services.

Palliative care providers typically offer different types of support which cut across these three components. Examples range from drop-in events and information evenings, telephone support, mutually supportive groups, individual and group counselling and specialist counselling for those with more complex needs.12,15,16 However, the evidence base for bereavement support in palliative care is limited, and comprehensive evidence synthesis around component one and two support has not previously been conducted. Reviews of supportive interventions for family caregivers have either excluded bereavement interventions,17 or due to the low number of well conducted, relevant studies have been unable to draw conclusions on effectiveness.18,19 Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of bereavement interventions are available that are not specific to bereaved caregivers with mixed results reported.20–25 Some have shown positive effects,24,25 while others have reported inconclusive results and limited effects.20–22,26,27 Some have also indicated that bereavement interventions may only be effective for those with more severe grief symptoms.20,22,27–31 However, the poor quality of many of these studies has been noted,23 including self-selecting and heterogeneous samples, absence of usual care control groups25 and inconsistent and inappropriate outcome measurement.20,21,26 Previous reviews have also not considered the qualitative or mixed-methods evidence for the wider range of support that is delivered in palliative care settings, which includes but is not limited to grief counselling.

This mixed-methods systematic review primarily considers the evidence on what could be considered NICE component two support, with only a small minority of studies reporting on component three type interventions targeted at high-risk groups. Evidence for component one type support (e.g. information leaflets, memorial events) is not included as these were considered too different in their purpose and content to enable meaningful comparison with the more sustained models of support considered in this review. A mixed-methods design was chosen not only to access evidence on models of support which are less likely to have been evaluated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs), but also because these types of interventions represent ‘complex interventions’. This means that they have multiple interacting components and outcomes, and associated challenges when it comes to evaluation.32,33 In recognising this complexity and the importance of understanding participant experiences, this review is informed by the epistemological and ontological commitments of critical realism34,35 and the methodological endeavours of realist and process evaluation.36–38 It considers evidence from all study designs, aiming to unpack the relationships between context, mechanisms and outcome,36–38 while also assessing the evidence for effectiveness.

Methods

A narrative systematic review was conducted39 which aimed to identify bereavement interventions and services reflective of NICE component two and three support for adults bereaved through advanced illness. It considers both the quantitative and qualitative evidence for their effectiveness and impact and the key features of their effective delivery.

Searches

Following development of a review protocol (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero, CRD42016043530), a comprehensive search was conducted on 15 April 2016. The databases Ovid MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycINFO and Ebsco CINAHL were searched for studies published from 1 January 1990. This search was updated in March 2019 and included an additional database – Social Policy and Practice that was not previously available. Reference list checking, citation tracking and contacting authors of included papers were conducted to avoid missing relevant studies. Relevant systematic reviews were also examined to identify eligible primary research.

Databases were searched using index terms and keywords. A set of bereavement/grief terms were identified and combined with a set of palliative care/advanced illness/caregiver terms. The Ovid MEDLINE search strategy is detailed in Supplementary File One. Results from the searches were imported into EndNote and duplicate references were removed.

Study selection

This mixed-methods review included evaluations of bereavement interventions reflective of NICE component two and three support, which reported results on effectiveness, impact and the key features of their successful delivery. Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to select studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| • Primary studies with a study population of adults bereaved

through advanced illness. • Written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals between 1990 and 2019. • From the United Kingdom or comparable countries where the research is likely to be applicable to the UK setting (North America, Western Europe and Australia/New Zealand). |

• Bereaved parents of children under 18 years of age and

adults bereaved through unexpected deaths. • Mixed populations (e.g. current and bereaved caregivers) where it was not possible to identify the impact of the intervention on the target population. • Purely information-based support (e.g. leaflets about grief and anniversary cards) or ‘one-time’ forms of support (e.g. memorial services, information evenings and post-death bereavement contact by medical/nursing staff). |

Relevant papers were identified by two independent reviewers, following a process of title, abstract and full-paper screening. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the reviewers.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted using a standardised Excel spreadsheet which was developed by the research team to summarise the included study characteristics and their results (Supplementary File Two). Quality assessment was conducted on all included studies using the appropriate GATE checklists.40 These were completed by four researchers and 20% were assessed by a second reviewer. Studies were rated as ‘good’ quality when all or almost all the critical appraisal criteria were scored as good, none of the criteria were rated as poor and none of the unfulfilled criteria were of high relevance (i.e. blinding of trial arm). Papers of mixed quality had many of the criteria rated as ‘good’ or ‘mixed’ and low-quality studies were those with a few criteria rated ‘good’ or ‘mixed’, meaning that study conclusions would have high risk of bias.

Data analysis and synthesis

Due to heterogeneity in intervention design and study outcomes, meta-analysis of quantitative results was not possible and a narrative synthesis was used instead. For qualitative studies, a further thematic synthesis of results was undertaken, following a three-stage process: coding text; development of descriptive themes; and analytical theme generation.41 PDF copies of included qualitative studies were uploaded into QSR NVivo V.10. Descriptive codes were inductively generated by three researchers through line-by-line coding of the relevant sections of results of each study. The data were re-reviewed by the main author to create a coding framework, and descriptive themes were organised into sets of analytical thematic hierarchies. These were reviewed and discussed by two researchers (E.H. and H.S.) to ensure rigour and reliability and to ensure that the themes reflected the results of the studies.

Results

Study characteristics and methodological quality

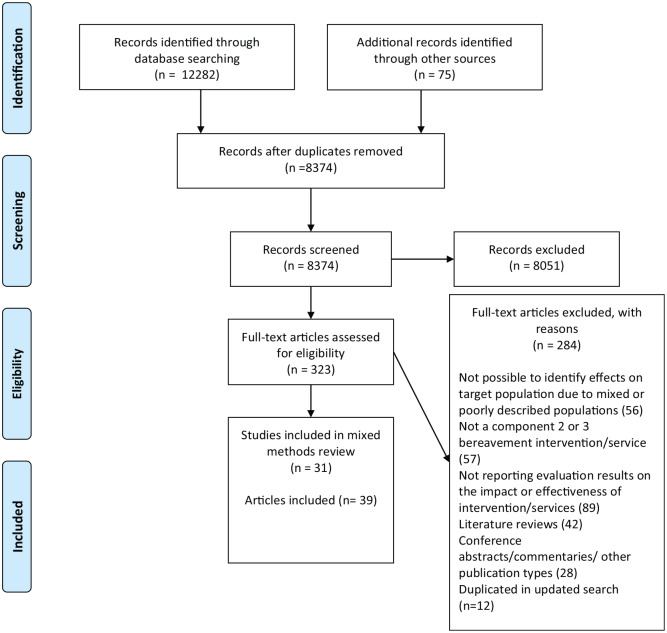

Following a process of title, abstract and full-paper screening, 31 studies (39 articles) were identified which met the inclusion criteria for this mixed-methods review (Figure 1). These included 15 effectiveness studies (combined n = 1893), and eight of which used randomised designs.42–49 The remainder of these 15 effectiveness studies used either uncontrolled before and after designs50–54 or included self-selecting comparison groups.55,56 Seven of these studies had very small samples sizes. The overall quality of many of these studies was therefore considered low.44,47,51–55 The three mixed-quality studies were limited by lack of random allocation56 or insufficient reporting on some methodological criteria.43,48,49 Only three trials were assessed as being of ‘good’ quality.42,45,46

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Twenty-one studies collected qualitative data to explore participant views or experiences of interventions, and one quantitative feedback survey was also included (combined n = 391). Six of these formed parts of the effectiveness studies cited above.42,44,46,47,50,51 The overall quality of these studies or study components varied, with six assessed as ‘good’ quality,50,57–61 10 studies (11 articles) as ‘mixed’ quality44,51,62–70 and six studies considered as ‘low’ quality.71–76 Study characteristics and quality scores are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study summary characteristics and results.

| First author and year | Design and quality score | Country | Intervention | Sample | Outcomes and measures/qualitative methods | Results | Included in narrative synthesis and/or thematic synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agnew 200962 | Qualitative Study (+) Focus group |

The United Kingdom | Bereavement support group, 10 monthly sessions Group support Professional led |

Seven bereaved hospice caregivers | Focus group Thematic analysis |

Key themes: Benefit from groups by feeling understood by others in similar situations Groups need to ‘feel safe’ in terms of where, when and what happens in them Groups need to offer the choice of listening or talking Groups should be inclusive and heterogeneous |

Thematic synthesis |

| Ando 201554 | Uncontrolled before and after (−) | The United States | Bereavement life review, two sessions 2 weeks

apart Individual support Professional led |

20 bereaved Hawaiian American caregivers of cancer patients | Depression (BDI-11) Spiritual well-being (FACIT-sp) |

Statistically significant increases in spirituality and decreases in depression | Narrative synthesis |

| Carter 200953 | Uncontrolled before and after (−) | The United States | CBT for chronic insomnia, two sessions 2 weeks

apart Individual support Professional led |

11 bereaved caregivers of cancer patients | Depressive symptoms (CESD) Sleep quality (PSQI, actigraphy, sleep logs, goal attainment scaling) |

Self-reported improvements in sleep and reduction in depressive symptoms | Narrative synthesis |

| Cronfalk 201066 | Qualitative study (+) | Sweden | Soft tissue massage, eight weekly sessions Individual support Professional led |

18 bereaved caregivers of cancer patients | Semi-structured interviews Qualitative content analysis |

Key themes: Comfort and hope through relationships and interaction with professionals Enabling rest, relaxation and feelings of peace Space to focus on grief during session and other areas of life at other times Forming new routines and structure in daily lives Regaining mastery and achieving personal development |

Thematic synthesis |

| Diamond 201263 | Mixed-methods qualitative component used (+) | The United Kingdom | Two hospice bereavement counselling

services Individual support Volunteer led with professional support for more complex cases |

13 volunteers 23 bereaved hospice clients |

Interviews used to administer quantitative and qualitative

tools (HAT) Qualitative content analysis of data collected in HAT |

Key themes: Clients gained insight, hope and reassurance from therapy sessions Helped by focusing on difficult emotions and issues Helped to explore options and engage in decision-making and looking ahead Helpful talking to those other than friends and family Consistent and trusting relationship enabled clients able to open up and express feelings |

Thematic synthesis |

| Di Mola 199073 | Qualitative study (−) | Italy | Family end-of-life home care with bereavement support

component Individual/family support Volunteer led |

33 volunteers Three groups (10–12 per group) |

Focus groups Analytical approach not described |

Key themes: Marginal role of volunteers in bereavement but main benefit seen as one of the continued companionship and sharing of important life events |

Thematic synthesis |

| Durepos 201759 | Qualitative study (++) | Canada | Psychoeducation caregiver support programme, ongoing weekly

sessions Group support Professional led |

Dementia caregiver participants (n = 9,

three of which were bereaved) Caregivers not attending group (n = 2) Healthcare professionals, including nurses and programme leaders (n = 5) |

Semi-structured interviews Qualitative content analysis |

Key themes: Strengthened community support Sharing coping strategies Sense of altruistic fulfilment by supporting others Challenges such as group dynamics, content preferences, uncertainty over attending post-death and practical difficulties with attending |

Thematic synthesis |

| Fegg 201342

Kogler 201361 |

RCT (++) Qualitative study (++) |

Germany | Existential behavioural therapy, six weekly groups for

caregivers in the last stage of life and during acute

bereavement (Control: usual treatment) Group support Professional led |

Main trial: 160 bereaved and current

carers Interviews: 16 bereaved caregivers of patients receiving palliative care |

Depression (BSI) Quality of life (SWLS, WHOQOL-BREF, QOL-NRS) Mood (PANAS) Semi-structured interviews Qualitative content analysis |

Significant between-group differences in self-reported

measures at 1 year for depression and one quality of life

measure (QOL-NRS). Other measures are

non-significant Qualitative themes: Learning coping strategies such as self-regulation, focusing on positive, mindfulness and avoiding preoccupation with negative thoughts Sharing coping strategies and learning from one another Feeling understood by peers, sense of belonging and togetherness Grief experiences understood as normal, enabling acceptance of these experiences Enabled self-disclosure and expression of emotions |

Narrative synthesis Thematic synthesis |

| Finley 201065 | Qualitative study (+) | The United Kingdom | Bereavement support groups at hospice, between four and

eight weekly sessions Group support Professional led |

70 bereaved caregivers | Audit of group records Thematic analysis |

Key themes: Family life, stories of death processes, grief and coping Themes noted in the records included loss, loneliness and practical issues |

|

| Goldstein 199672 | Cross-sectional survey (−) | The United States | Bereavement support group involving psychodynamic approaches

and supportive educational techniques, eight

sessions Group support Professional led |

Five bereaved adults from cancer centre | Five-point Likert-type scale to assess helpful features of group | Participants rated following questionnaire items as

‘useful’: Learning coping strategies Helping others by sharing strategies, information and offering support Normalisation of grief process Being able to speak to ‘strangers’ about experiences without risk of alienating family and friends |

Narrative synthesis |

| Goodman 200955 | Cross-sectional survey (−) | The United States | One secular hospice support group One Christian support group Group support |

83 bereaved individuals (49 attending hospice group) | Hopelessness (BHS) Religious coping (RCOPE) |

No statistically significant differences between two groups | Narrative synthesis |

| Goodkin 199843

Goodkin 199977 |

RCT (+) | The United States | Bereavement support group, 10 weekly

sessions (Control: usual treatment) Group support Professional led |

119 bereaved gay men (HIV positive and negative) | Immunological function (HIV-related cell

counts) Neuroendocrine (plasma cortisol level) Healthcare visits Distress/grief (TRIG/POMS) Secondary measures (ad hoc complicated grief index and SIGH-AD) |

At 6 months statistically significant between-group

differences in some HIV-related cell counts, plasma cortisol

level and healthcare utilisation At 10 weeks statistically significant between overall group differences in composite distress/grief scores and distress component of score and in controlled analysis on grief measures |

Narrative synthesis |

| Holtslander 201644 | RCT (−) Qualitative study (+) |

Canada | Finding balance writing tool with examples and exercises.

Used over 2 weeks (Control: wait list) Individual support at home Self-administered tool |

19 bereaved older caregivers of cancer patients | Feasibility data Hope, coping and balance (HHI, HGRC and IDWL) Qualitative questions asked at follow-up Qualitative content analysis |

Statistically significant difference in self-reported

coping; IDWL restoration-oriented scale Qualitative themes: Validation of emotions and helping themselves to move forward Focusing on new ideas in finding balance The timing of the intervention |

Narrative synthesis Thematic synthesis |

| Hopmeyer 199474 | Cross-sectional survey (−) | Canada | Bereavement support group (closed membership), bi-weekly for

six to eight sessions. Educational material presented and

discussed Group support Peer facilitation with social worker in attendance |

Bereaved family members of cancer patients (n not stated) | Free-text survey responses with ranking

exercise Analysis of qualitative data not described |

Key themes: Place to vent experience Chance to talk and opportunity to share grief and support Comforting not to be alone and feeling similar to others Gender differences in preferences for group content |

Thematic synthesis |

| Houldin 199352 | Uncontrolled before and after (−) | The United States | Relaxation training, four weekly sessions Mix of individual and group support Professional led |

Nine bereaved widows of cancer patients | Anxiety (STAI) Depression (BDI) Immunological assays (blood tests) |

Self-reported mild to moderate improvements in appetite and sleep patterns | Narrative synthesis |

| Johnson 201567 | Qualitative study (+) | The United Kingdom | District nurses delivering home-based bereavement

support Individual/family support Professional led |

Five district nurses delivering support | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

Key themes: Nurses can become too involved with clients Lack of formal training and education on bereavement, but learning through experience just as valuable Having good rapport and trust with families enables better care |

Thematic synthesis |

| Kissane 199875 | Qualitative study (−) Piloting of Family Focused Grief Therapy |

Australia | Development and piloting of FFGT (see Kissane et al.45) | Three families of cancer patients used as case studies to explore how intervention helped them (15 ‘high-risk’ families participated in pilot study) | Practitioner observation | Therapist observations: The ‘family that finds it hard to trust’ became more cohesive, intimate and supportive of one another The ‘family that listens but doesn’t hear’ acted more cohesively became more communicative and understanding and experienced less conflict as a result. They were more able to comfort each other in grief The ‘family hampered by conflict’ became more understanding and sharing |

Thematic synthesis |

| Kissane 200645 | RCT (++) (randomised by family) |

Australia | FFGT, four to eight sessions spread over

9–18 months (Control: no treatment) Family support Professional led |

81 families of current becoming bereaved carers, identified as ‘at risk’ of poor social outcome (363 participants) | Distress (BSI) Depression (BDI) Social adjustment (SAS) |

Between-group differences were non-significant except brief symptom inventory scores | Narrative synthesis |

| Kissane 201646

Mondia 201268 Del Gaudio 201369 |

RCT (++) (randomised by family) Qualitative studies (+) |

The United States | Family grief therapy, six or 10 sessions over

7 months (Control: standard care) Family support Professional led |

170 families of current becoming bereaved caregivers of

cancer patients identified as ‘at risk’ of poor social

outcome (620 participants) Therapy sessions of eight minority ethnic families analysed55,56 |

Complicated grief (CGI) Depression (BDI-11) Recordings and supervision notes of therapy sessions analysed qualitatively |

Significant treatment effects found on CGI, but not the

BDI-11. Better outcomes resulted for low-communicating and high-conflict groups in the 10 session trial arm, when compared with the standard care arm. Qualitative finding: need for therapists to possess appropriate cultural knowledge when working with minority ethnic families |

Narrative synthesis Thematic synthesis |

| Lieberman 199249 | RCT (+) | The United States | Brief group psychotherapy, eight sessions (Control: no treatment) Group support Professional led |

56 bereaved spouses of cancer patients | Mental health: depression, anxiety and somatization (adapted

HSC scales) Use of psychotropic medication and alcohol (five-item scale) Mourning (author developed scales)Positive psychological states: psychological well-being (Bradburn Affect Balance Scale) Locus of control (PCMS) Self esteem (RSES) Social adjustment: Single role strainStigma (author scale) |

Significant effects on measures of self-esteem and role strain. All other measures non-significant | Narrative synthesis |

| McGuinness 201147

McGuinness 201564 |

RCT (−) Qualitative study (+) |

Ireland | Creative arts group therapy, eight weekly

sessions (Control: wait list) Group support Professional led |

20 bereaved hospice caregivers | Grief (AAG and TRIG) Service evaluation questionnaires with open and closed questions Group-based feedback Content analysis of qualitative data |

No significant between-group differences on quantitative

outcomes Qualitative themes: Peer support and connectedness Enabled expression of grief and emotions Participants experienced increased confidence and feelings of strength when facing the loss Understanding grief as a ‘process or journey’ Helpful talking to ‘strangers’ about experiences |

Narrative synthesis Thematic synthesis |

| Nappa 201556 | Controlled before and after (+) | Sweden | Bereavement support group, five weekly

sessions Control: two groups – those ‘unable to take part’ and those who chose not to take part Group support Professional led |

124 bereaved cancer caregivers | Grief (TRIG) Anxiety/depression (HADS) |

No significant between-group differences on either outcome when comparing intervention group and those unable to take part | Narrative synthesis |

| Picton 200157 | Qualitative study (++) | Australia | Bereavement support groups, eight weekly

sessions Group support Professional led |

17 bereaved relatives of cancer patients | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

Key themes: Majority of participants described the benefits of early participation, with minority favouring later entry to support programme |

Thematic synthesis |

| Pomeroy 200251 | Uncontrolled before and after (−) Qualitative study (+) |

The United States | Bereavement support group, six weekly sessions Group support Professional led |

Five bereaved carers of a person with AIDS | Anxiety (STAI), Depression (BDI), Grief (grief experience

inventory) Despair (despair subscale) Participant observation using field notes |

Significant differences pre- and post-test for anxiety and

grief symptoms Qualitative themes: Connectedness and sharing of experiences, feelings and coping strategies Movement from hopelessness to hopefulness |

Narrative synthesis Thematic synthesis |

| Reid 200670

Field 200780 |

Qualitative study (+) | The United Kingdom | Multi-faceted support at five hospices, including befriending support, formal counselling and therapeutic group | Paid and voluntary staff and bereavement service users from five hospices (n not stated) | Case studies involving semi-structured interviews, focus

groups and documentary analysis Thematic analysis |

Key themes: Bereavement counselling/befriending programmes facilitated expression of emotions, normalisation of grief process and feelings. Seen as helpful to talk to someone other than friends and family Befriending provides practical and social support, including ‘listening ear’, but there are concerns over when to withdraw Therapeutic group helped by meeting others in similar situations and learning coping strategies |

Thematic synthesis |

| Roberts 200871 | Cross-sectional survey (−) | Ireland | Volunteer listening service (VBSS) Individual support Volunteer led |

76 service user respondents to questionnaire evaluating hospice VBSS | Open and closed questions in survey Qualitative analysis not described |

Key themes: Insight gained on the grief process, including understanding feelings as ‘normal’ Clients helped to open up and express emotions and valued feeling ‘listened to’ Clients valued talking to those other than friends and family and having a safe ‘space’ to grieve |

Thematic synthesis |

| Sikkema 200448

Sikkema 200579 Sikkema 200678 |

RCT (+) | The United States | Group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, 12 weekly

sessions (Control: individual therapy on request) Group support Professional led |

268 bereaved individuals with HIV positive status | Grief (GRI), Psychiatric distress (SCL-90R) and Depression

(SIGH-AD) Health-related quality of life (FAHI) |

Significant between-group differences were only identified on measures of psychiatric distress48 and health-related quality of life79 | Narrative synthesis |

| Supiano 201758 | Qualitative study (++) | The United States | Complicated grief group therapy, five weekly sessions over

16 weeks Group support Professional led |

16 bereaved dementia caregivers, three treatment groups | Observation of three therapy sessions in RCT Sessions coded using the ‘meaning of loss codebook’ |

Key observations: Over time, participants demonstrated positive gains in the domain of ‘moving on with life’ Participant interpretations of the death transitioned from negative to positive and positive memories started to be shared |

Thematic synthesis |

| Wittenberg-Lyles 201550 | Uncontrolled before and after (−) Qualitative study (++) |

The United States | Closed Facebook group Online support group Written information and guidance provided to facilitate discussion |

16 bereaved hospice carers | Depression-patient health questionnaire

(PHQ-9) Generalised anxiety disorder Screening tool (GAD-7) Qualitative content analysis of online posts |

Lower levels of anxiety and depression pre-/post-test. Not

reported if these were significant Qualitative themes: Sharing of coping strategies, advice and storytelling Sense of community and mutual support Understanding feelings as normal |

Narrative synthesis Thematic synthesis |

| Yopp76 | Qualitative study (−) | The United States | Bereavement support group for widowed fathers, seven monthly

sessions Group support Professional led |

Six bereaved husbands (with dependent children) at cancer centre | Focus group Analysis not described |

Key themes: Feeling understood by others in similar situations and comforted by not being alone Understanding grief experiences as normal Learning and sharing coping strategies, including those relating to parental competencies and concerns |

Thematic synthesis |

| Young 201860 | Qualitative study (++) | Canada | Music therapy, six singing sessions over

3 months Group support Professional led |

Seven bereaved female caregivers | Semi-structured interviews Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

Key themes: Enabled profound emotional expression and mutual support Facilitated emotional and spiritual connection to the deceased Helpful opportunity for grief resolution Some experienced discomfort, nervousness and anxiety |

Thematic synthesis |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; FACIT-sp: spiritual well-being scale; CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CESD: Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; HAT: Helpful Aspects of Therapy; RCT: randomised controlled trials; BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory; SWLS: Satisfaction With Life Scale; WHOQOL-BREF: WHO Quality of Life – BREF; QOL-NRS: Numeric Rating Scale for Quality of Life; PANAS: Positive and Negative Affect Scale; BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale; RCOPE: Religious Coping Scale; TRIG: Texas Revised Inventory of Grief; POMS: Profile of Moods States; SIGH-AD: Structured Interview Guide for Hamilton Anxiety and Depression; HHI: Herth Hope Index; HGRC: Hogan Grief Reaction Checklist; IDWL: Inventory of Daily Widowed Life; FFGT: Family Focused Grief Therapy; SAS: Social Adjustment Scale; CGI: Complicated Grief Inventory; HSC: Hopkins Symptom Checklist; PCMS: Pearlin Coping Mastery Scale; RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; AAG: Adult Attitude to Grief Scale; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; STAI: State Trait Anxiety Inventory; VBSS: Volunteer Bereavement Support Service; GRI: Grief Reaction Index; SCL-90R: Symptom Checklist Revised; FAHI: Functional Assessment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: Generalised Anxiety Disorder Screening Tool.

Quality score: ++ (good quality), + (mixed quality) and − (low quality).40

Types of interventions and services

A wide variety of interventions are included in this review. Most common were bereavement support and social groups (n = 12) and psychological and counselling interventions (n = 10). Other types included creative arts, writing and music interventions (n = 3), befriending and home-visiting support (n = 4) and relaxation and massage interventions (n = 2). These interventions represented a mix of individual (n = 12), family (n = 2) and group-based (n = 19) support and varied in the number of sessions and length of time over which they ran. Most commonly, they were delivered by professionals (n = 25), but some were led by volunteers, which included trained volunteer counsellors as well as members of the public in ‘befriending’ roles (n = 5). Three interventions were peer- or self-led. The study populations included bereaved relatives of specific patient groups (cancer n = 13, dementia n = 2 and HIV/AIDS n = 3), as well as general bereaved caregiver populations (n = 13). Almost all studies reported on what could be considered NICE component two support (n = 27). Only two interventions (four studies) provided specialist (component three) support to those pre-identified as ‘at risk’45,46,58,75 and two studies evaluated hospice services which provided a mix of support.63,70 A matrix detailing the different approaches is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Types of bereavement support interventions.

| One-to-one/family setting | Group setting | |

|---|---|---|

| Professional led | Psychological and counselling: Family Focused Grief Therapy (FFGT)a45,46,75 Supportive counsellinga63,70 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for chronic insomnia53 Bereavement Life Review54 Others: Relaxation training52 Home support67 Soft tissue massage66 |

Bereavement support groups43,51,55,56,57,59,62,70,76

Psychological and counselling: Psychodynamic therapy with supportive educational techniques72 Complicated Grief Group Therapya58 Existential Behaviour Therapy (EBT)42 CBT48 Group psychotherapy49 Others: Creative arts therapy47 Music therapy60 Relaxation training52 |

| Volunteer led | Supportive counselling63,70

Informal home visits73 Volunteer bereavement support/befriending services70,71 |

|

| Peer/self-led | Finding Balance writing tool44 | Social groups (face to face)74

Social groups (online)50 |

Included targeted support for high-risk groups.

Evidence for effectiveness

A total of 15 effectiveness studies (18 papers) were included in this section, and seven of which were RCTs. Three ‘good-quality’ RCTs introduced support for caregivers during the end-of-life period, continuing into bereavement.42,45,46 The Existential Behaviour Therapy (EBT) intervention was delivered to groups of current and bereaved caregivers over six weekly sessions.42 The Family Focused Grief Therapy (FFGT) intervention was evaluated in two RCTs45,46 and delivered to families identified as at risk of poor social outcomes. The first FFGT trial was conducted in Australia and involved four to eight support sessions spread over 9–18 months, depending on individual family needs.45 The second study was a three-arm trial conducted in the United States, with six or 10 sessions provided over 7 months.46

In the EBT trial, significant between-group differences were reported in self-reported anxiety and all three quality of life measures post-intervention, and in depression and one quality of life measures at 1-year follow-up.42 In the first FFGT trial, a significant reduction in distress was identified at 13-month follow-up. No effects were found on social adjustment and depression overall, but for the 10% of families treated with FFGT who were most troubled at baseline, significant improvements in depression occurred. There were also differences by ‘type’ of family, with some family types benefitting more than others.45 When conducted in the United States, using a measure of complicated grief, significant treatment effects were found for low-communicating and high-conflict families, but not for low-involvement families. No significant treatment effects were found for depression.46

Three ‘mixed-quality’ RCTs43,48,49 and one ‘mixed-quality’ controlled before and after study56 evaluated group-based interventions delivered to bereaved partners or spouses of HIV/AIDS43,48 and cancer patients.49,56 Participants in the HIV/AIDS-specific groups had also been diagnosed as HIV positive43,48 or were at increased risk of such diagnosis.43 The support was delivered over five,56 six,49 1043 and 1248 sessions. One of the AIDS interventions used the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT),48 and one of the cancer-specific group involved psychotherapy.49 Significant between-group differences were reported in distress, healthcare utilisation and immunological/biological measures in the HIV/AIDS bereavement support group trial43,77 and in distress and quality of life in the CBT trial.48,79 No significant overall differences were found on measures of grief or depression in either trial,48,77 but participants with higher levels of distress in the CBT group were found to have significantly lower grief severity scores than distressed participants in the comparison group who were accessing individual therapy.78 In the psychotherapy group trial for spouses of cancer patients, significant between-group differences were found on measures of self-esteem and role strain, but not on grief, depression or other health and well-being outcomes.49 In contrast with the CBT trial,78 improvements were not found to be greater for at risk individuals receiving psychotherapy compared with at risk controls.49 No benefits of the support group for bereaved cancer caregivers were found on measures of grief, anxiety or depression compared with non-participant controls.56

Of the eight ‘low-quality’ effectiveness studies, seven had 20 participants or fewer making their results at best indicative. Of these, two used randomly assigned comparison groups.44,47 Apart from significant between-group differences in self-reported coping for a creative writing intervention,44 differences were non-significant for all other outcomes. The other five studies were uncontrolled before and after studies, further limiting their evidence. Statistically significant improvements in study outcomes pre- and post-intervention were reported for Bereavement Life Review54 and a bereavement support group for people bereaved through AIDS.51 Non-significant self-reported improvements were reported for a CBT insomnia intervention,53 relaxation training52 and an online support group.50 In a cross-sectional study comparing the effectiveness of two self-selecting groups (a Christian-oriented approach with a psychological-oriented one), no significant differences were found between groups in measures of coping or hopelessness.55

Evidence on the impact of interventions

Twenty-one studies used qualitative or mixed-methods and one study used a quantitative survey design. Six of these (eight papers) collected qualitative data as part of the effectiveness studies reported above.44,47,50,51,61,64,68,69 Through thematic synthesis, many positive impacts for participants were identified. The results of the quantitative survey are also reported in relation to these themes.72 The impact-related themes are described under the headings: ‘loss and grief resolution’, ‘sense of mastery and moving ahead’ and ‘social support’.

Loss and grief resolution

Three studies described how individual counselling helped service users gain insight and perspective and facilitated the normalisation of the grief process.63,70,71 Positive relationships with counsellors enabled clients to open up, feel ‘listened to’ and facilitated their expression of emotions.63,70,71 Participants in these studies also noted the importance of being able to talk to those other than friends and family63,70,71 and having a safe ‘space’ to grieve:71

“Talking helped to make sense of it” (client); “It showed all her low times were during school holiday . . . something she’d known but had not acknowledged. It’s much clearer particularly about the low times”. (Volunteer)63

Similar therapeutic impacts were observed in 11 stud-ies which evaluated group-based interventions44,47,50,51,58,60,61,64,72,74,76 and a self-led writing intervention.44 In a Complicated Grief Group Therapy intervention, it was observed how participant interpretations of the death transitioned from negative to positive over the course of the treatment.58 More generally, the sharing of experiences helped service users to understand their grief experiences as normal44,60,61,72,76 and as a process or journey.44,47 These understandings in turn helped them to accept these experiences61 and ‘not fear’ their feelings.47 Groups in five studies were found to be helpful for enabling self-disclosure and the expression of grief, emotions and the ‘venting’ of experience,51,60,61,64,74 as well as pleasant memories.58 In the music therapy group, participants described how the spiritual connection to the deceased that they experienced helped to resolve their grief.60 In an AIDS-specific support group, members became able to see the positive impact of their loved one in their present life, as they transitioned from feelings of hopelessness to hopefulness.51 The importance of being able to speak to ‘strangers’ about their experiences, without risk of alienating family and friends, was also observed.47,70,72 It was noted, however, that some participants had trouble revealing their emotions:47

Everybody has cried at least once. One doesn’t have to hide it, that’s the nice thing. And we shared this with each other. (Participant)61

Sense of mastery and moving ahead

Twelve studies described benefits relating to coping, mastery and moving ahead. The massage intervention was recognised as having provided participants with the ‘space’ to focus on their grief during the session. This enabled them to focus on other areas of life at other times, while also helping them to start forming new routines and structure in their daily lives. By accessing help, they experienced a sense of mastery and personal development, which gave them hope for the future.66 The ‘finding balance’ writing intervention was similarly identified as helping participants identify new ways of achieving balance in their lives.44 Counselling services in two hospice-based studies were also seen to have enabled participants to explore options and engage in decision-making and looking ahead, again supporting feelings of hope and reassurance:63,70

. . . it helps me in talking over things but it actually picks me up and puts me back on another set of rails so that I can go forwards. (Service user)70

Similar benefits were identified in group support interventions. Eight studies positively described the learning and sharing of coping strategies within the groups.50,51,59,61,70,72,74,76 In the EBT group, such strategies included self-regulation, focusing on the positives, mindfulness and avoiding preoccupation with negative thoughts.61 Participants in the online group shared examples of ‘turning points’ in their own coping and restorative processes, as well as practical strategies for dealing with loss-related stressors.50 Positive gains in the domain of ‘moving on with life’ were similarly observed in the complicated grief therapy group.58 Bereaved participants in the writing intervention and group for current and bereaved dementia caregivers were reported to achieve a sense of purpose and altruistic fulfilment by helping others through sharing their experiences and stories:44,59

It (mindfulness) is like meditating. And the important thing is not to hold on to these bad thoughts or things, but rather to know that they are there and that that is okay, but that one will get out of this again. (Participant)61

In the group for bereaved fathers, the guidance and support shared between members helped with doubts and concerns relating to parenting.76

Social support

Social benefits of group-based support were identified in 11 studies, including one online community.50 These included benefits such as emotional support, sharing and feeling understood by others in similar situations,47,50,51,59,61,62,65,70,74,76 feelings of belonging, community and connectedness50,51,59,60,61,64,76 and comfort from not being alone.47,74,76 Continuing contact and improvements to social lives after the groups had finished were also noted:70,76

I don’t feel so alone and lost, it has made me feel stronger and I feel we have united like friends when you most need a friend. (Participant)64

Interpersonal benefits were also identified for four individual-level interventions66,70,71,73 and one family-based intervention.75 It was noted how support from volunteers provided ‘companionship’,73 practical and social support and a ‘listening ear’.70,71 In the massage intervention, participants valued having their feelings recognised and took comfort and hope from these relationships.66 In a qualitative study used to develop the family grief therapy intervention, social benefits were reported relating to family functioning and dynamics. These included improved cohesion, support, understanding and sharing within the family.76

Features of effective delivery

Several themes were identified in relation to the contexts and processes underpinning effective intervention delivery. Interpersonal factors such as positive relationships between group members, clients and counsellors were seen as critical to the success of the support,61,63,71,73,76,80 as was the need for therapists and volunteers to possess appropriate cultural and experiential knowledge of community grief processes and norms.67–69 The importance of continuity between pre- and post-bereavement support for families was also widely acknowledged, seen as leading to better bereavement care, either by provision of information about bereaved relatives or by the rapport and trust that was needed to support families after death.61,67,73,80 However, potential difficulties associated with service users becoming dependent on the support, and related ‘boundary’ issues for volunteers were identified in two studies.67,70

In terms of group content and composition, the need for groups to be informal, but with an explicit purpose and structure was identified.62 The value of inclusive and heterogeneous groups for optimising shared learning opportunities was also recognised.61,62 With regard to the timing of support, participant preferences varied within and between studies suggesting that there is no ‘right time’ to offer support.44,57,63

Discussion

Main findings of the review

This mixed-methods systematic review has considered the evidence on a wide range of interventions for people bereaved through advanced disease. Lack of high-quality RCTs and heterogeneity in study outcomes, intervention design and populations meant that the conclusions that can be drawn on effectiveness are limited. The thematic synthesis of qualitative results, however, identified consistent benefits for participants across studies and intervention types, and helps illuminate the mechanisms through which this support impacts upon participant experiences. Although the interventions varied considerably, three core impacts are identified which connect with the concepts of resilience and public health approaches to bereavement care.

What this review adds

Small sample sizes and uncontrolled study designs meant that just over half of the effectiveness studies included in this review were graded as low quality and their results were of limited value. Results from the larger, better quality studies varied, but almost all reported significant positive effects on some study outcomes. Among the four ‘mixed-quality’ studies of group-based interventions, significant effects were found on measures of distress,48,77 quality of life,48 immunological function and health43 for the two HIV/AIDS-specific groups, but not grief or depression.48,77 Evaluations of group psychotherapy49 and a bereavement support group56 for bereaved cancer caregivers also found no effects of the interventions on grief or depression,49,56 although significant effects were reported on measures of self-esteem and role strain for the psychotherapy intervention.49

Only three good-quality RCTs were included. Two of these evaluated FFGT interventions delivered to ‘at-risk’ families in Australia and the United States.45,46 There was a significant reduction in distress reported in the Australian study45 and significant improvements in complicated grief symptoms in the American study.46 Variations by type of family were also observed,45,46 and for families most troubled at baseline, significant improvements in depression occurred.45 These results suggest that FFGT can improve psychological and grief outcomes for some at-risk families. This fits with findings of other reviews on the enhanced benefits of grief therapy for most at risk/symptomatic groups.20,22,24,27,28,31 The other good-quality trial was of a group-based EBT intervention for family caregivers conducted in Germany. This reported significant intervention effects on anxiety, depression and quality of life,42 with benefits also identified in the associated qualitative evaluation.61 Both interventions were introduced to family caregivers in the end-of-life period, indicating the value of such approaches. The qualitative evidence reported in this review,59,61,67,73,80 and other studies81 also suggests the benefits of continuity between pre- and post-death support and is in-line with guidance recommending that bereavement risk assessment and targeted support begins in the pre-death period.12,13

In the thematic synthesis, three core impacts and mechanisms of impact were identified which cut across the different types of support. These are described as ‘loss and grief resolution’, ‘sense of mastery and moving ahead’ and ‘social support’. Only three of the 21 studies included in the synthesis were targeted at populations categorised as ‘high risk’.58,68,69,75 Therapeutic benefits relating to loss and grief resolution were apparent in many individual counselling and group-based programmes of support. By facilitating emotional expression, the discussion of troubling concerns and the normalisation of grief, service users gained insight and perspective on their experiences and became more accepting of their grief. Through mastery of specific coping techniques such as channelling, mindfulness and positive thinking, as well as more general decision-making capabilities, participants experienced enhanced feelings of control, hopefulness and an ability to look ahead and move forwards. These apparent impact pathways fit well with the Dual Process Model (DPM) of grief adaptation,82 as well as conceptualisations of ‘balanced’ responses to the emotional and practical consequences of loss.83 The DPM model posits that bereaved people oscillate between dealing with the loss of the deceased person (loss-orientated coping) and negotiating the practical and psychosocial changes to their lives that occur as a result of the bereavement (restoration-orientated coping). These two processes both appear to be positively enhanced by interventions included in the synthesis through the mechanisms described above. These findings also suggest the critical role of meaning reconstruction84,85 within this loss-oriented grief work, as bereaved people strive to make sense of and come to terms with their loss.

For group-based programmes, various social support–related benefits were also widely reported, including feelings of connectedness, belonging and comfort. These were linked with the sharing of experiences and sense of understanding developed between those in similar situations. The benefits of companionship with volunteer ‘befrienders’ and the comfort derived from empathetic relationships with professional counsellors were also observed for some individual-level interventions. The opportunity to confide in those outside of existing networks was valued for individual- and group-based models. Although perceived lack of social support is recognised as a risk factor for problematic grief experiences,86,87 social support is often overlooked in quantitative evaluations of bereavement care.88 However, as this synthesis suggests, this type of impact is widely valued and of high perceived importance to service users. This fits with public health approaches which recognise the importance of existing social networks for all bereaved people, but also advocate for a second tier of non-specialist, community–based support for those at moderate risk of complex grief, and who may lack adequate social support.1,2

Taken together these three main types of impacts (loss resolution, moving ahead and social support) also fit with broader resilience and meaning-based coping frameworks in public health research. Such frameworks converge over their identification of individual, family and community level resources which facilitate coping and adaptation to adversity.89 The role of meaning making, comprehensibility and feelings of manageability in maintaining one’s ‘sense of coherence’ is also theorised in salutogenic approaches to maintaining health and well-being, thus again resonating with some of the mechanistic themes identified here.89,90 The concept of resilience has been used by some bereavement researchers and practitioners to theorise healthy adaptations to grief,15,83,91,92 with calls for further work to explore strategies which promote resilience in bereavement.15,92 This synthesis suggests the value of such approaches for conceptualising and targeting the mechanisms through which bereavement support can improve the resilience and coping capabilities of service users.

Strengths and limitations of the review

By focusing on support for people bereaved through advanced illness, and adopting a mixed-methods approach, this review has addressed some of the gaps in the review-level evidence relating to bereavement support in palliative care. Through the thematic synthesis of qualitative results, it has identified several core mechanisms through which this support benefits participants, and which can help inform future service design. However, by restricting to these population groups, it is likely that we missed potentially relevant specialist counselling and grief therapy interventions. These are not typically restricted in this way, but have been the subject of previously discussed reviews. By defining our population in this way, our final set of interventions included those involving general palliative care populations as well as disease-specific populations such as HIV/AIDS and dementia. The distinctive emotional and psychosocial issues associated with loss through dementia58,59 and loss through/living with HIV/AIDS43,48,51 may also mean that these study results do not fully generalise beyond those specific populations. A further limitation is that the review only included research which was published in English and based in the United Kingdom and countries considered most comparable in terms of cultures, economic and social and healthcare systems. As such we may have missed out on potentially informative studies from the wider international literature.

Implications for further research

A key finding of this review, in common with others, has been the poor quality of many of the included studies. Only a small number of RCTs were identified, while small sample sizes and heterogeneity in populations, models of care and study outcomes further compromised the usefulness of the quantitative evidence. The apparent contrast between the pathological outcomes most commonly used in the quantitative studies (e.g. depression and distress) and the coping and support-oriented impacts that were identified in the thematic synthesis also raises questions over the appropriateness of some of these outcomes for evaluating bereavement care.26,88 The recent stakeholder-based identification of two core outcomes for evaluating bereavement support in palliative care (‘ability to cope with grief’ and ‘quality of life and mental well-being’) outlines a more consistent and seemingly appropriate way forward for outcome measurement in this area of research,88 with potential to improve the comparability and relevance of study results.

More generally, there is a need for more high-quality quantitative and qualitative evaluations of these types of bereavement support. Given the difficulties associated with conducting RCTs of complex interventions generally,32 and in palliative care specifically,93,94 we adopt a critical position which challenges traditional evidence hierarchies95 in favour of more inclusive approaches to public health evidence production and utilisation. Further consideration should be given not just to improving trial design through embedded qualitative studies and process evaluations,32,38 but also the contribution that alternative practice-based evaluation methods might make.96 The value of thematic synthesis for exploring causal mechanisms and contextual factors was well-demonstrated in this review and should be further utilised for evidence reviews of these types of complex interventions, along with more theory-driven, mixed-methods approaches such as realist synthesis.33,36

Conclusion

A variety of bereavement interventions were considered in this review; however, the overall conclusions that may be drawn on their effectiveness are limited by the quality and comparability of the quantitative evidence. Good-quality trial evidence was only available for targeted Family Grief Therapy and a non-targeted group–based therapy intervention, both of which were introduced during the caregiving period and found to be at least partially effective. The thematic synthesis identified several core benefits that were common across a range of individual- and group-level interventions, most of which were not targeted at high-risk groups. These benefits related to loss resolution, moving ahead and social support. The synthesis identified key mechanisms which produce these impacts, and in doing so suggests the value of peer support alongside opportunities for reflection, emotional expression and restoration-focused activities for those with moderate-level needs. These findings reiterate the importance of tiered public health approaches to bereavement care, with different types of support available and accessed appropriately according to need. High-quality, mixed-methods evaluations are needed to further determine and explain the relative value of such support for different groups of bereaved populations.

Footnotes

Author contributions: E.H. drafted the paper and oversaw the project. A.B., A.N., J.F., K.S., S.S., E.H. and F.M. developed the search strategy and F.M. conducted the searches. E.H., L.S., F.M. and H.S. screened articles for inclusion and were involved in data extraction and quality appraisal. M.L. also assisted with quality appraisal of included studies. E.H. conducted the thematic synthesis with assistance from H.S. and L.S. All authors contributed to the drafting of the paper and read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Marie Curie Research Grant (grant no. MCCC-RP-16-A20999). The project was also supported by the Marie Curie core grant funding to the Marie Curie Research Centre, Cardiff University (grant no. MCCC-FCO-11-C). E.H., A.N., A.B., S.S. and M.L. posts are supported by the Marie Curie core grant funding (grant no. MCCC-FCO-11-C). The funder was not involved in the study design, implementation, analysis or interpretation of results, and has not contributed to this manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Emily Harrop  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2820-0023

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2820-0023

Annmarie Nelson  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6075-8425

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6075-8425

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Aoun SM, Breen LJ, O’Connor M, et al. A public health approach to bereavement support services in palliative care. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012; 36(1): 14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aoun SM, Breen LJ, Howting DA, et al. Who needs bereavement support? A population based survey of bereavement risk and support need. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(3): e0121101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Onrust SA, Cuijpers P. Mood and anxiety disorders in widowhood: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health 2006; 10(4): 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet 2007; 370(9603): 1960–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, et al. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017; 212: 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, et al. Prolonged grief disorder: psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med 2009; 6(8): e1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lobb EA, Kristjanson L, Aoun S, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud 2010; 34(8): 673–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shear MK, Ghesquiere A, Glickman K. Bereavement and complicated grief. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013; 15(11): 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, et al. Predictors of complicated grief and depression in bereaved caregivers: a nationwide prospective cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53(3): 540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chiu YW, Huang CT, Yin SM, et al. Determinants of complicated grief in caregivers who cared for terminal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2010; 18(10): 1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hudson P, Remedios C, Zordan R, et al. Guidelines for the psychosocial and bereavement support of family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Palliat Med 2012; 15(6): 696–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hudson P, Hall C, Boughey A, et al. Bereavement support standards and bereavement care pathway for quality palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2018; 16(4): 375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guidance on cancer services: improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer. The manual. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization. National cancer control programmes: policies and managerial guidelines, 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Field D, Reid D, Payne S, et al. Survey of UK hospice and specialist palliative care adult bereavement services. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004; 10(12): 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guldin MB, Murphy I, Keegan O, et al. Bereavement care provision in Europe: a survey by the EAPC Bereavement Care Taskforce. Eur J Palliat Care 2015; 22(4): 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hudson P, Remedios C, Thomas K. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for family carers of palliative care patients. BMC Palliat Care 2010; 9: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, et al. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 6: CD007617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gauthier LR, Gagliese L. Bereavement interventions, end-of-life cancer care, and spousal well-being: a systematic review. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract 2012; 19(1): 72–92. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wittouck C, Van Autreve S, De Jaegere E, et al. The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31(1): 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Forte AL, Hill M, Pazder R, et al. Bereavement care interventions: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2004; 3(1): 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Currier JM, Neimeyer RA, Berman JS. The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for bereaved persons: a comprehensive quantitative review. Psychol Bull 2008; 134(5): 648–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kato PM, Mann T. A synthesis of psychological interventions for the bereaved. Clin Psychol Rev 1999; 19(3): 275–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johannsen M, Damholdt MF, Zachariae R, et al. Psychological interventions for grief in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord 2019; 253: 69–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waller A, Turon H, Mansfield E, et al. Assisting the bereaved: a systematic review of the evidence for grief counselling. Palliat Med 2016; 30(2): 132–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jordan JR, Neimeyer RA. Does grief counseling work? Death Stud 2003; 27(9): 765–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schut H, Stroebe MS, van den Bout J, et al. The efficacy of bereavement interventions: determining who benefits. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, et al. (eds) Handbook of bereavement research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001, pp. 705–738. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neimeyer RA. Grief counselling and therapy: the case for hope. Bereave Care 2010; 29(2): 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boelen PA, de Keijser J, van den Hout MA, et al. Treatment of complicated grief: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counselling. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007; 75(2): 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, et al. Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 293(21): 2601–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Neimeyer RA, Currier JM. Grief therapy: evidence of efficacy and emerging directions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2009; 18(6): 352–356. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008; 337: a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, et al. Guidance on choosing qualitative evidence synthesis methods for use in health technology assessments of complex interventions. Bremen: Integrate-HTA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bhaskar R. A realist theory of science. London: Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rorty RM, Rorty R. Philosophy and social hope. London: Penguin, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kasi MAF. Realistic evaluation in practice. London: SAGE, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005; 10(Suppl. 1): 21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015; 350: h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme, version 1, 2006, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.178.3100&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- 40. Jackson R, Ameratunga S, Broad J, et al. The GATE frame: critical appraisal with pictures. Evid Based Med 2006; 11(2): 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fegg MJ, Brandstatter M, Kogler M, et al. Existential behavioural therapy for informal caregivers of palliative patients: a randomised controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology 2013; 22(9): 2079–2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goodkin K, Feaster DJ, Asthana D, et al. A bereavement support group intervention is longitudinally associated with salutary effects on the CD4 cell count and number of physician visits. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1998; 5(3): 382–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Holtslander L, Duggleby W, Teucher U, et al. Developing and pilot-testing a finding balance intervention for older adult bereaved family caregivers: a randomized feasibility trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016; 21: 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kissane DW, McKenzie M, Bloch S, et al. Family focused grief therapy: a randomized, controlled trial in palliative care and bereavement. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163(7): 1208–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kissane DW, Zaider TI, Li Y, et al. Randomized controlled trial of family therapy in advanced cancer continued into bereavement. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(16): 1921–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McGuinness B, Finucane N. Evaluating a creative arts bereavement support intervention: innovation and rigour. Bereave Care 2011; 30(1): 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, et al. Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of a group intervention for HIV positive men and women coping with AIDS-related loss and bereavement. Death Stud 2004; 28(3): 187–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lieberman MA, Yalom I. Brief group psychotherapy for the spousally bereaved: a controlled study. Int J Group Psychother 1992; 42(1): 117–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K, Oliver DP, et al. ‘It is the “starting over” part that is so hard’: using an online group to support hospice bereavement. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13(2): 351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pomeroy EC, Holleran LK. Tuesdays with fellow travelers: a psychoeducational HIV/AIDS-related bereavement group. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv 2002; 1(2): 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Houldin AD, McCorkle R, Lowery BJ. Relaxation training and psychoimmunological status of bereaved spouses. Cancer Nurs 1993; 16(1): 47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carter PA, Mikan SQ, Simpson C. A feasibility study of a two-session home-based cognitive behavioral therapy–insomnia intervention for bereaved family caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2009; 7(2): 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ando M, Marquez-Wong F, Simon GB, et al. Bereavement life review improves spiritual well-being and ameliorates depression among American caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13(2): 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Goodman H, Jr, Stone MH. The efficacy of adult Christian support groups in coping with the death of a significant loved one. J Relig Health 2009; 48(3): 305–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Näppä U, Lundgren AB, Axelsson B. The effect of bereavement groups on grief, anxiety, and depression: a controlled, prospective intervention study. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Picton C, Cooper BK, Close D, et al. Bereavement support groups: timing of participation and reasons for joining. Omega: J Death Dying 2001; 43(3): 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Supiano KP, Haynes LB, Pond V. The process of change in complicated grief group therapy for bereaved dementia caregivers: an evaluation using the meaning of loss codebook. J Gerontol Soc Work 2017; 60(2): 155–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Durepos P, Kaasalainen S, Carroll S, et al. Perceptions of a c program for caregivers of persons with dementia at end of life: a qualitative study. Aging Ment Health 2019; 23(2): 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Young L, Pringle A. Lived experiences of singing in a community hospice bereavement support music therapy group. Bereave Care 2018; 37(2): 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kögler M, Brandl J, Brandstätter M, et al. Determinants of the effect of existential behavioral therapy for bereaved partners: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2013; 16(11): 1410–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Agnew A, Duffy J. Effecting positive change with bereaved service users in a hospice setting. Int J Palliat Nurs 2009; 15(3): 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Diamond H, Llewelyn S, Relf M, et al. helpful aspects of bereavement support for adults following an expected death: volunteers’ and bereaved people’s perspectives. Death Stud 2012; 36(6): 541–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McGuinness B, Finucane N, Roberts A. A hospice-based bereavement support group using creative arts: an exploratory study. Illn Crisis Loss 2015; 23(4): 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Finley R, Payne M. A retrospective records audit of bereaved carers’ groups. Groupwork 2012; 20(2): 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cronfalk BS, Ternestedt BM, Strang P. Soft tissue massage: early intervention for relatives whose family members died in palliative cancer care. J Clin Nurs 2010; 19(7–8): 1040–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Johnson A. Role of district and community nurses in bereavement care: a qualitative study. Br J Community Nurs 2015; 20(10): 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mondia S, Hichenberg S, Kerr E, et al. The impact of Asian American value systems on palliative care: illustrative cases from the family-focused grief therapy trial. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012; 29(6): 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Del Gaudio F, Hichenberg S, Eisenberg M, et al. Latino values in the context of palliative care: illustrative cases from the family focused grief therapy trial. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013; 30(3): 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Reid D, Field D, Payne S, et al. Adult bereavement in five English hospices: types of support. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006; 12(9): 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Roberts A, McGilloway S. The nature and use of bereavement support services in a hospice setting. Palliat Med 2008; 22(5): 612–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Goldstein J, Alter CL, Axelrod R. A psychoeducational bereavement-support group for families provided in an outpatient cancer center. J Cancer Educ 1996; 11(4): 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Di Mola G, Tamburini M, Fusco C. The role of volunteers in alleviating grief. J Palliat Care 1990; 6(1): 6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hopmeyer E, Werk A. A comparative study of family bereavement groups. Death Stud 1994; 18(3): 243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kissane DW, Bloch S, McKenzie M, et al. Family grief therapy: a preliminary account of a new model to promote healthy family functioning during palliative care and bereavement. Psycho-Oncology 1998; 7(1): 14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yopp J, Rosenstein DL. A support group for fathers whose partners died from cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2013; 17(2): 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]