Abstract

Bovine lactoferrin (bLF) has been extensively described as a wide spectrum antimicrobial protein. bLF bactericidal activity has been mainly attributed to two different mechanisms: environmental iron depletion and cell membrane destabilization. Due to its antimicrobial properties, bLF has been included in the formulation nutraceutical food products and edible active packages. This work comprises the experimental evidence of the requirement of bLF unrestricted mobility (“free bLF”) to effectively perform its bactericidal action. To assess the unrestricted and restricted bLF activity, a nontoxic matrix of bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) was used as carrier, and as an anchoring scaffold, respectively. Therefore, BNC was functionalized with bLF through two different methodologies: (i) bLF was embedded within the three-dimensional structure of BNC and; (ii) bLF was covalently bounded to the nanofibrils of BNC. bLF efficiency was tested against two bacteria isolated from clinical specimens, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. bLF concentration after covalent binding to BNC was two-fold higher in comparison to the embedding method. Nevertheless, only the embedded bLF exhibited a significant bactericidal activity, due to bLF ability to permeate the BNC matrix and execute its bactericidal action.

Keywords: Materials science, Food technology, Microbiology, Bacterial nanocellulose, Bovine lactoferrin, Antibacterial protein activity

Materials science; Food technology; Microbiology; Bacterial nanocellulose; Bovine lactoferrin; Antibacterial protein activity

1. Introduction

Bacterial infections are becoming a serious public health threat due to the antibiotic discovery void, and the alarming increase of antimicrobial resistance. Therefore, the full potential of novel bio-based antimicrobial agents is being target of intensive research. Particularly due to their effectiveness and their lower predisposition to induce resistance [1, 2]. The innate immune system encompasses several antimicrobial proteins, such as lactoferrin (LF), which are regarded as the host first line of defence [3, 4]. LF is a cationic iron-binding glycoprotein, expressed in a multitude of mammal secretions, reaching up to 0.4 mg mL−1 in bovine milk [5]. Bovine lactoferrin (bLF) consistently exhibited a bactericidal action against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [6, 7, 8]. bLF proposed bactericidal activity may be grouped into to two main mechanisms: membrane destabilization, and environmental iron depletion due to its iron chelating properties [9]. bLF interacts and disrupts the bacteria membrane due to its amphipathic N-terminal domain, its high cation net charge, its high isoelectric point, and its lipopolysaccharide binding domain [10, 11, 12]. To the best of the authors knowledge, mechanistic correlation between the bLF properties and bactericidal action is not well studied, with no report being published in the current literature. Therefore, to evaluate if the mobility of bLF is a determinant factor for its antibacterial activity, bLF was immobilized onto a biocompatible scaffold. Bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) was the selected scaffold due to its extreme high purity and non-toxicity [13, 14]. BNC is a three-dimensional matrix composed of multiple single cellulose I nanofibrils synthesized by bacteria, [15, 16]. BNC surface functionalization was widely explored for multiple applications, encompassing biomedical, textile and food packaging applications [13, 14, 17, 18, 19]. Sodium periodate oxidation represents a simple strategy to covalently bind target proteins onto polysaccharides, such as BNC [20]. When an individual glucan unit of BNC is oxidised, an aldehyde is formed in C-2 and C-3, allowing a subsequent nucleophilic attack by the ε-NH2 present in lysine residues of bLF, generating carbinolamines [21, 22].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microorganisms, culture media and materials

BNC was produced using Gluconacetobacter xylinus ATCC 53582 cultured in Hestrin Schramm (HS) medium (pH 5.5) in 6 well-plates, each containing 10 mL of HS medium and incubated for 21 days, in static conditions at 30 °C [23]. BNC purification process was similar to the described by Padrão and co-workers [7]. The bactericidal assessment assays were performed using Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical specimens cultured in Muller Hinton (MH) agar. All bLF solutions were prepared using phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and filter-sterilized (polytetrafluoroethylene membrane, pore size: 0.22 μm), immediately prior to their use. bLF was purchased to DMV International (96 % (w/w) bLF with approximately 120 pp of iron).

2.2. Periodate oxidation of bacterial nanocellulose

Purified BNC cylindrical membranes of 4.8 cm3 (3.5 cm diameter and 0.5 cm height) were autoclaved and stored in distilled water until further use. BNC membranes were immersed in a sodium periodate aqueous solution at a molar ratio 1:1, at 50 °C under mild agitation and protected from light. Periodate decomposition and concomitantly the percentage of BNC oxidation was analysed through the measurement of the optical density (at 290 nm) using an ultra-violet visible spectrometer [24]. In the end of the reaction, the oxidised BNC samples were thoroughly washed in sterile distilled water and immediately immersed in the bLF solutions. Control BNC membranes, without periodate oxidation, were defined by the acronym: 0BNC. Oxidised BNC membranes with 25 % of oxidation (approximately 3425 μg g−1 of aldehyde group content) and 75 % of oxidation (nearly 9400 μg g−1 of aldehyde group content) were defined as 25BNC and 75BNC, respectively. Oxidation profile was adjusted to a logistic model growth (Eq. 1) to determine the reaction parameters [25].

| (1) |

where, X corresponds to the BNC oxidation percentage, Xmax corresponds to the maximum oxidation level, X0 to the instantaneous oxidation, μ defines the oxidation rate and t the reaction time.

2.3. Bovine lactoferrin binding to bacterial nanocellulose

0BNC, 25BNC and 75BNC membranes were immersed in bLF solutions (1 membrane in 10 mL of bLF solution) with different concentrations (0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 mg mL−1), and subjected to mild shaking for 24 h at room temperature. Afterwards, membranes were rinsed with sterile distilled water to remove excess of bLF. Concentration of bLF into BNC was estimated indirectly by Bradford protein assay. The BNC membranes containing bLF were defined, according to their percentage of oxidation and bLF solution concentration as: 0BNC+0.25bLF, 0BNC+0.5bLF, 0BNC+1bLF, 0BNC+2bLF, 25BNC+0.25bLF, 25BNC+0.5BLF, 25BNC+1bLF, 25BNC+2bLF, 75BNC+0.25bLF, 75BNC+0.5bLF, 75BNC+1bLF, 75BNC+2bLF.

2.4. Characterization

0BNC, 25BNC and 75BNC, and membranes that exhibited a higher concentration of bLF (0BNC+2bLF, 25BNC+2bLF and 75BNC+2bLF) were further characterized. All the prepared BNC membranes were analysed after drying in a desiccator at room temperature, until the mass of respective membrane remains constant. The microstructure analysis of the different oxidation percentages was achieved using a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (NanoSEM - FEI Nova 200 (FEG/SEM)) with an accelerating voltage of 2 kV, after magneton gold sputtering (Polaron, model SC502).

Water contact angle (WCA) was measured through static sessile drop method using ultrapure water (3 μL droplets) as test liquid at room temperature (Data Physics OCA20). A minimum of 6 measurements were performed in distinct locations for each sample, and the average contact angle was estimated.

Attenuated total reflectance mode of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) was performed using 64 scans ranging from 4000 to 600 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 (Jasco FT/IR-4100).

2.5. Determination of the antimicrobial activity using the disk diffusion susceptibility test

The bactericidal activity of the 0BNC, 0BNC+2bLF, 25BNC and 25BNC+2bLF membranes was evaluated through the disk diffusion susceptibility assay. The followed experimental procedure was described by Wiegand and collaborators [26]. Briefly, McFarland 0.5 turbidity standard was used to define the inoculum concentration in PBS for each bacterium (1–2 x 108 colony forming units (CFU) mL−1), which was evenly spread on MH agar plates. BNC disks with 9.8 mm3 (5 mm diameter and 5 mm height), obtained using a sterilized puncher, were carefully placed on the plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Zone of inhibition (ZoI) including the BNC disk diameter was estimated using Image J software 1.45s (National Institutes of Health) of high resolution photographs [27].

2.6. Statistical analysis

All results displayed a parametric distribution and were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-test. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad, Inc.) using an alpha value of 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

BNC periodate oxidation is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

BNC periodate oxidation reaction. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error, obtained from three independent assays (n = 3). The dashed line represents the modelled oxidation profile estimated using logistic growth equation (Eq. (1)).

After 4 h of reaction, the aldehyde group content reached approximately 5600 μmol g−1, roughly 1.2 fold-lower than the achieved in cellulose nanocrystals in similar conditions [28]. Unlike cellulose nanocrystals, BNC fibrils provide a degree of tortuosity within its structure, not immediately exposing all its cellulose units to periodate oxidation. This may explain the slower rate of oxidation observed after 8 h.

Figure 2 displays the uptake of bLF by BNC. Two carbonyl groups per unit of glucose are generated by periodate oxidation and these functional group are available to form carbinolamines with bLF lysine residue ε-NH2, through a nucleophilic attack [21].

Figure 2.

bLF concentration in BNC oxidised with sodium periodate: 0 % (0BNC), 25 % (25BNC) and 75 % (75BNC); after 24 h immersed in bLF solution of 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 mg mL−1. Different column letters denote significant differences determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test (p < 0.05). Results are expressed in mean ± standard error (n = 3).

25BNC+1bLF, 25BNC+2bLF and all the 75BNC + bLF membranes show a higher bLF concentration in comparison to the 0BNC + bLF. This difference may be attributed to the covalent bounds between bLF and BNC through the formation of carbinolamines. For 0BNC + bLF and 25BNC + bLF, bLF concentration displays direct correlation between bLF uptake and bLF concentration in the solution. All 75BNC + bLF samples displayed an identical (p > 0.05) bLF uptake (approximately 13 mg mL−1 bLF g−1 BNC), due to the higher aldehyde content. No differences (p > 0.05) were observed between all the 75BNC and the 25BNC+2bLF, exhibiting an uptake of 14.2 mg mL−1 bLF g−1 BNC. Considering the BNC volumetric mass density of 0.86 mg mm−3, the estimated concentration of bLF in each disk of 9.8 mm3 was 0.06 mg mL−1 and 0.12 mg mL−1 for 0BNC+2bLF and 25BNC+2bLF, respectively [7].

No topological differences were observable between 25BNC, 75BNC, 25BNC+2bLF and 75BNC+2bLF SEM images (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Microstructure of oxidized BNC with and without bLF. (a) 25BNC, (b) 75BNC, (c) 25BNC+2bLF and (d) 75BNC+2bLF.

Therefore, oxidation percentage and uptake of bLF did not resulted in obvious morphological modifications of BNC. The preservation of the original BNC scaffold structure after periodate oxidation was also previously reported [22]. Sodium periodate has this considerable advantage over other oxidizing agents, since it minimizes degradation and maintains both mechanical and architectural properties of the pristine polysaccharides [29].

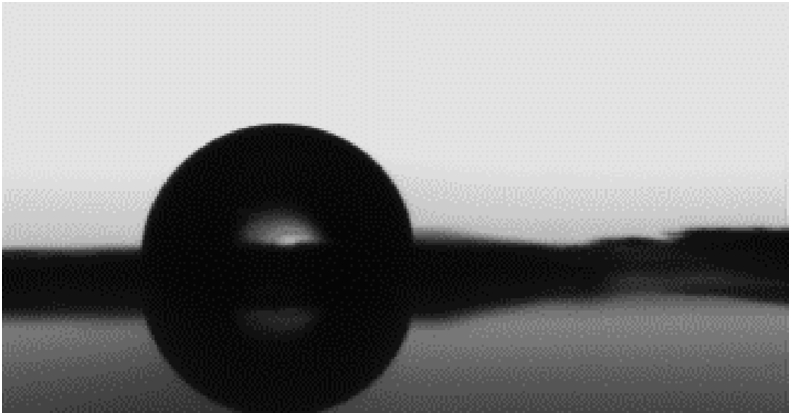

WCA is a sensitive method to characterize surface wettability, which plays a critical role in protein adsorption and repulsion, protein aggregation and protein displacement [30]. The average WCA values of oxidised BNC with and without bLF are represented in Table 1, and a typical measurement of the WCA is depicted in Figure 4.

Table 1.

Average WCA values of BNC membranes with different oxidation levels (0, 25 and 75 %), with and without bLF.

| Oxidation (%) | Water contact angle (o) |

|

|---|---|---|

| BNC | BNC+2bLF | |

| 0 | 22.77 ± 4.32 | 48.93 ± 7.96 |

| 25 | 22.70 ± 1.59 | 85.10 ± 5 .67 |

| 75 | 42.77 ± 2.78 | 87.85 ± 4.70 |

Figure 4.

A photograph of a typical WCA measurement.

WCA of 0BNC and 25BNC without bLF is similar, whereas 75BNC exhibited a 2-fold increase, reaching the value of 42.77°. Roughness and chemical modification are the major factors to influence WCA. No BNC structural changes were observed in the SEM images; thus, the extensive oxidation of 75BNC was the main responsible for WCA increase [31]. The WCA increase of 75BNC maybe due to the formation of and intra and intermolecular hemialdal and hemiacetal groups during the drying process [32]. Nevertheless, all the samples without bLF still exhibited a hydrophilic behaviour (WCA <90°) [33]. The incorporation of bLF resulted in a considerable increase of the WCA value, denoting the impact of bLF hydrophobic amino acids residues in the WCA [34]. Interestingly, 25BNC+2bLF and 75BNC+2bLF exhibited a similar WCA value, most likely due to their similar load of bLF. Therefore, WCA measurements were sensitive to extensive BNC oxidation, and to bLF concentration present in BNC.

Figure 5 depicts FTIR-ATR spectra.

Figure 5.

FTIR-ATR spectra of 25BNC, 75BNC, 25BNC+2bLF and 75BNC+2bLF. Characteristic BNC and bLF bands are highlighted by the dashed lines.

Oxidized BNC samples exhibit characteristic absorbance bands similar to pristine BNC, namely: hydroxyl stretching vibration (3350 cm−1) and aldehyde stretching (2891 cm−1) [7,28]. 75BNC exhibits a more sharper carbonyl stretching at approximately 1640 cm−1 than 25BNC, highlighting the more extensive periodate oxidation [35, 36, 37]. The presence of bLF in the BNC is denoted by the characteristic protein Amide I (carbonyl stretching) and Amide II (carbon-nitrogen and nitrogen-hydrogen bending) absorbance bands (approximately at 1640 cm−1 and 1535 cm−1, respectively) [7].

After assessing the presence of bLF in the BNC samples, and inferring the higher bLF content in oxidized BNC due to covalent binding, the selected oxidized sample for the bactericidal activity evaluation was 25BNC+2bLF. The rationale of this choice was based on the similar bLF uptake with minimal BNC oxidation. The bactericidal performance of bLF through ZoI analysis is present in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

ZoI (including the diameter of the BNC disk) displayed by 0BNC, 25BNC, 0BNC+2bLF and 25BNC+2bLF after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, in contact with: (a) E. coli and (b) S. aureus. Different column letters denote significant differences determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test (p < 0.05). Results are expressed in mean ± standard error, obtained from four independent assays (n = 3).

As expected, the 0BNC and 25BNC exhibited a minimal ZoI identical to the disk diameter (ranging between 5 mm and 8 mm), denoting their non-toxic behaviour, proving the adequacy of BNC for the intended purpose. The minor ZoI, observed were likely formed due to a PBS leaching effect. 0BNC+2bLF membranes contain bLF embedded within the nanomatrix of BNC, it has been demonstrated that, when immersed in a solution, the bLF is gradually released in the medium [7]. Free bLF of 0BNC+2bLF samples was able to exert a bactericidal activity showing a significant ZoI against E. coli and S. aureus. On the other hand, 25BNC+2bLF, despite its two-fold higher bLF concentration than 0BNC+2bLF, displayed a lower ZoI. In fact, against S. aureus, its effect was similar to the control samples. The significant bactericidal activity displayed by the 25BNC+2bLF against E. coli may be associated to the chelating of divalent ions by bLF domains leading to the destabilization the outer membrane of this Gram-negative bacterium [38].

Despite the observed significant ZoIs, according to Rota and colleagues scale, a ZoI lower or equal to 12 mm is considered a weak bactericidal activity [39]. This may be due to the high bLF concentrations required for its effective bactericidal activity [6]. Nevertheless, this methodology was sufficient to provide an insight of the impact of covalent binding between the bLF lysine residue ε-NH2 and the BNC in its bactericidal activity.

4. Conclusions

This work highlights the correlation between the bLF mobility and its bactericidal activity. Several publications report the bLF indirect bactericidal action, nevertheless the results herein obtained show a significant reduction of the bLF bactericidal activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, when it is covalently bound, despite its higher concentration (2-fold). The use of proteins and peptides with bactericidal properties still represents an underestimated strategy to target multi-drug resistant bacteria. Future biotechnological solutions should assure that the used bLF is not covalently bound or immobilized, otherwise, regardless of the concentration, bLF bactericidal activity will be significantly impaired.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Jorge Padre: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Sylvie Ribeiro: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Senentxu Lanceros-Menent, Lígia R. Rodrigues, Fernando Dourado: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the scope of the strategic funding of UIDB/04469/2020 unit and BioTecNorte operation (NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000004) funded by the European Regional Development Fund under the scope of Norte2020 - Programa Operacional Regional do Norte. This work was also supported by the FCT in the framework of the Strategic Funding of UID/FIS/04650/2020 and projects PTDC/BTM-MAT/28237/2017 and PTDC/EMDEMD/28159/2017. The authors acknowledge funding by the Spanish State Research Agency (AEI) and the European Regional Development Fund through the project PID2019-106099RB-C43/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and from the Basque Government Industry and Education Department under the ELKARTEK, HAZITEK and PIBA (PIBA-2018-06) programs, respectively. In addition, J. Padrão (SFRH/BD/64901/2009) and S. Ribeiro (SFRH/BD/111478/2015) would like to acknowledge their doctoral grants awarded by FTC.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Silver L.L. Challenges of antibacterial discovery. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24:71–109. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00030-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown E.D., Wright G.D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamauchi K., Wakabayashi H., Shin K., Takase M. Bovine lactoferrin: benefits and mechanism of action against infections. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2006;84:291–296. doi: 10.1139/o06-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González-Chávez S.A., Arévalo-Gallegos S., Rascón-Cruz Q. Lactoferrin: structure, function and applications. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2009;33:301.e1–301.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakabayashi H., Yamauchi K., Takase M. Lactoferrin research, technology and applications. Int. Dairy J. 2006;16:1241–1251. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padrão J., Machado R., Casal M., Lanceros-Méndez S., Rodrigues L.R., Dourado F., Sencadas V. Antibacterial performance of bovine lactoferrin-fish gelatine electrospun membranes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;81 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padrão J., Gonçalves S., Silva J.P., Sencadas V., Lanceros-Méndez S., Pinheiro A.C., Vicente A.A., Rodrigues L.R., Dourado F. Bacterial cellulose-lactoferrin as an antimicrobial edible packaging. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;58 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado R., da Costa A., Silva D.M., Gomes A.C., Casal M., Sencadas V. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of poly(lactic acid)–bovine lactoferrin nanofiber membranes. Macromol. Biosci. 2018;18:1700324. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201700324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang R., Lönnerdal B. Bovine lactoferrin and lactoferricin exert antitumor activities on human colorectal cancer cells (HT-29) by activating various signaling pathways. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2016;95:99–109. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2016-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomita M., Bellamy W., Takase M., Yamauchi K., Wakabayashi H., Kawase K. Potent antibacterial peptides generated by pepsin digestion of bovine lactoferrin. J. Dairy Sci. 1991;74:4137–4142. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha M., Kaushik S., Kaur P., Sharma S., Singh T.P. Antimicrobial lactoferrin peptides: the hidden players in the protective function of a multifunctional protein. Int. J. Pept. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/390230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naidu S.S., Erdei J., Czirók É., Kalfas S., Gadó I., Thorén A., Forsgren A., Naidu S.A. Specific binding of lactoferrin to Escherichia coli isolated from human intestinal infections. APMIS. 1991;99:1142–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonçalves S., Padrão J., Rodrigues I.P., Silva J.P., Sencadas V., Lanceros-Mendez S., Girão H., Dourado F., Rodrigues L.R. Bacterial cellulose as a support for the growth of retinal pigment epithelium. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16 doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampaio L.M.P., Padrão J., Faria J., Silva J.P., Silva C.J., Dourado F., Zille A. Laccase immobilization on bacterial nanocellulose membranes: antimicrobial, kinetic and stability properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;145 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benziman M., Haigler C.H., Brown R.M., White A.R., Cooper K.M. Cellulose biogenesis: polymerization and crystallization are coupled processes in Acetobacter xylinum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:6678–6682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamanaka S., Sugiyama J. Structural modification of bacterial cellulose. Cellulose. 2000;7:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gama F.M., Klemm D. CRC press; Boca Raton: 2013. Bacterial nanocellulose - a sophisticated multifunctional material. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonçalves S., Rodrigues I.P., Padrão J., Silva J.P., Sencadas V., Lanceros-Mendez S., Girão H., Gama F.M., Dourado F., Rodrigues L.R. Acetylated bacterial cellulose coated with urinary bladder matrix as a substrate for retinal pigment epithelium. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2016;139 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes M., Gama M., Dourado F., Souto A.P. Development of novel bacterial cellulose composites for the textile and shoe industry. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019;12:650–661. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su W.-Y., Chen Y.-C., Lin F.-H. Injectable oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel for nucleus pulposus regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3044–3055. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanderson C.J., Wilson D.V. A simple method for coupling proteins to insoluble polysaccharides. Immunology. 1971;20:1061–1065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J., Wan Y., Li L., Liang H., Wang J. Preparation and characterization of 2,3-dialdehyde bacterial cellulose for potential biodegradable tissue engineering scaffolds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2009;29:1635–1642. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hestrin S., Schramm M. Synthesis of cellulose by Acetobacter xylinum. II. Preparation of freeze-dried cells capable of polymerizing glucose to cellulose. Biochem. J. 1954;58:345–352. doi: 10.1042/bj0580345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tummalapalli M., Gupta B. A UV-Vis spectrophotometric method for the estimation of aldehyde groups in periodate-oxidized polysaccharides using 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2015;34:338–348. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsoularis A., Wallace J. Analysis of logistic growth models. Math. Biosci. 2002;179:21–55. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiegand I., Hilpert K., Hancock R.E.W. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:163. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun B., Hou Q., Liu Z., Ni Y. Sodium periodate oxidation of cellulose nanocrystal and its application as a paper wet strength additive. Cellulose. 2015;22:1135–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchens S.A., Benson R.S., Evans B.R., Rawn C.J., O’Neill H. A resorbable calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite hydrogel composite for osseous regeneration. Cellulose. 2009;16:887. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasan A., Pandey L.M. Review: polymers, surface-modified polymers, and self assembled monolayers as surface-modifying agents for biomaterials. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2015;54:1358–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Y., Cao X., Feng X., Ma Y., Zou H. Fabrication of super-hydrophobic film from PMMA with intrinsic water contact angle below 90°. Polymer (Guildf) 2007;48:7455–7460. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plappert S.F., Quraishi S., Pircher N., Mikkonen K.S., Veigel S., Klinger K.M., Potthast A., Rosenau T., Liebner F.W. Transparent, flexible, and strong 2,3-dialdehyde cellulose films with high oxygen barrier properties. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19:2969–2978. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.8b00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan Y., Lee T.R. Contact angle and wetting properties. In: Bracco G., Holst B., editors. Surf. Sci. Tech. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2013. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aftabuddin M., Kundu S. Hydrophobic, hydrophilic, and charged amino acid networks within protein. Biophys. J. 2007;93:225–231. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.098004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keshk S.M.A.S., Ramadan A.M., Bondock S. Physicochemical characterization of novel Schiff bases derived from developed bacterial cellulose 2,3-dialdehyde. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;127:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim U.-J., Kuga S., Wada M., Okano T., Kondo T. Periodate oxidation of crystalline cellulose. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1:488–492. doi: 10.1021/bm0000337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dash R., Elder T., Ragauskas A.J. Grafting of model primary amine compounds to cellulose nanowhiskers through periodate oxidation. Cellulose. 2012;19:2069–2079. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi P., Giansanti F., Boffi A., Ajello M., Valenti P., Chiancone E., Antonini G. Ca2+ binding to bovine lactoferrin enhances protein stability and influences the release of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2002;80:41–48. doi: 10.1139/o01-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rota M.C., Herrera A., Martínez R.M., Sotomayor J.A., Jordán M.J. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of Thymus vulgaris, Thymus zygis and Thymus hyemalis essential oils. Food Contr. 2008;19:681–687. [Google Scholar]