Abstract

Kaempferol (KMF) is a member of flavonol widely found in tea, broccoli, apples, strawberries, and beans. It has been demonstrated to present several pharmacological properties with potent antimalarial activity against Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. Hence, the search for a safe and new antimalarial compound with combinations to delay the development of resistance was the aim of this study. Thus, the therapeutic effect of the combination of KMF and artesunate (ART) in P. berghei-infected mice was evaluated. Combination of KMF and ART in P. berghei ANKA- (PbANKA-) infected ICR mice in a fixed-ratio combination (1 : 1) and fractions of their median effective dose (ED50) was also investigated using the standard 4-day suppressive test. The ED50 levels of KMF and ART in mice infected with PbANKA were 20.06 ± 2.65 and 6.06 ± 1.33 mg/kg, respectively. Moreover, KMF showed promising synergistic combination with ART at the doses of their ED50 and fixed-ratio combination (1 : 1) of their ED50 of 1/2 with combination index (CI) values of 0.86 and 0.47, respectively. Additionally, KMF, ART, and its combination at the doses of their ED50 and fixed-ratio combination (1 : 1) of their ED50 of 1/2 also presented significantly (P < 0.001) prolonged mean survival time (MST). The findings of this study showed that a combination of KMF and ART enhanced the antimalarial activity of ART and prolonged MST. This study supports the basis for the selection of KMF as a prospective compound for further consideration as a partner drug for ART.

1. Introduction

Malaria remains one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity accounting for about 10% of childhood deaths in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. In 2018, it was estimated that 228 million cases of malaria and 405,000 malaria-related deaths occurred in the world [2]. The resistance of Plasmodium parasites to available antimalarial drugs especially to artemisinin and the delayed parasite clearance with the artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) has led to increase treatment failure [3–6]. Hence, the search for safe and selective chemotherapeutic drugs with efficacy that will not be compromised by Plasmodium remains the focus.

Kaempferol, a flavonol widely found in different vegetables (tea, broccoli, apples, strawberries, and beans), is known to be one of the most active and important natural compounds with several pharmacological properties including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer [7–9]. Moreover, kaempferol has been studied and found to be an important compound in the search for an effective antimalarial drug against Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium berghei-infected mice [10, 11]. However, the possible application of a combination of kaempferol with widely used artemisinin derivative, artesunate, in combating malaria has not yet been investigated. Therefore, this study was aimed to investigate the therapeutic effect of a combination of kaempferol and artesunate in P. berghei-infected mice using in vivo model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drugs and Reagents

Artesunate (ART), kaempferol (KMF), and Tween-80 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All reagents were of analytical grade. The selected doses of ART and KMF were prepared in 20% Tween-80 and administered orally by gavage. The untreated group was given 20% Tween-80 only.

2.2. Experimental Mice

ICR male mice, 4–6 weeks old, weighing 25–30 g at the time of primary infection were used throughout this study. They were obtained from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Mahidol University, Thailand, and kept in an animal room with temperatures of 22–25°C, 12 h light-dark cycle. The animals were allowed free access ad libitum to a pellet diet and clean water. All experiments involving experimental mice were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Walailak University (AE002/2019).

2.3. Rodent Malaria Parasite

In this study, chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium berghei strain ANKA (PbANKA) obtained from Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center (MR4, https://www.beiresources.org/About/MR4.aspx) was used. The parasite was maintained by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 1 × 107 parasitized erythrocytes of PbANKA into naïve ICR mice. Propagation of parasite was monitored by microscopy of Wright-Giemsa stained blood film, and percent parasitemia was subsequently calculated using

| (1) |

2.4. Antimalarial Suppressive Test

The ED50 of ART and KMF was estimated using the standard 4-day suppressive test as previously described [12]. Forty-five naïve ICR mice were infected with 1 × 107 parasitized erythrocytes of PbANKA by IP injection. After 2 h, the mice were divided into 9 groups of 5 mice each. The test groups were given KMF (1, 5, 20, and 100 mg/kg) and ART (1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg) orally. The untreated group received 10 ml/kg of 20% Tween-80. The drugs were treated once a day for 4-consecutive days (D0–D3). At D4, parasitemia was estimated using microscopy of Wright-Giemsa stained thin blood film, and percent parasite suppression was subsequently calculated using

| (2) |

2.5. In Vivo Antimalarial Combination Test

In order to obtain the combination potency of the ART and KMF, antimalarial activity was assayed using the standard 4-days suppressive test previously described above. Twenty naïve ICR mice were administered by IP infection with 1 × 107 parasitized erythrocytes of PbANKA. After 2 h, the mice were divided into 5 groups of 5 mice each and given the combination drugs at the doses of their respective ED50 and fixed-ratio combination (1 : 1) of their respective ED50 1/2, 1/4, and 1/8. The untreated group was given 10 ml/kg of 20% Tween-80. The treatment was carried out once a day for 4-consecutive days (D0–D3). Parasitemia and percent suppression of parasite growth were subsequently calculated on D4.

2.6. Determination of Mean Survival Time

The mortality of all experimental mice was daily monitored, and the number of days from parasite inoculation up to death was recorded throughout the follow-up period. The mean survival time (MST) was calculated using the following formula [13]:

| (3) |

2.7. Statistics

All results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software version 5.01, Inc., USA). The nonlinear regression function for the sigmoidal dose-response variable slope was used to calculate the best-fit ED50. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used to compare the mean of measured parameters. The P < 0.05 at 95% confidence was regarded as statistically significant. Moreover, a combination index (CI), which defines synergism (CI < 1), additive effect (CI = 1), and antagonism (CI > 1), was automatically simulated by CompuSyn (CompuSyn software, ComboSyn, Inc., USA) [14].

3. Results

3.1. Antimalarial Activity of KMF and ART against PbANKA-Infected Mice

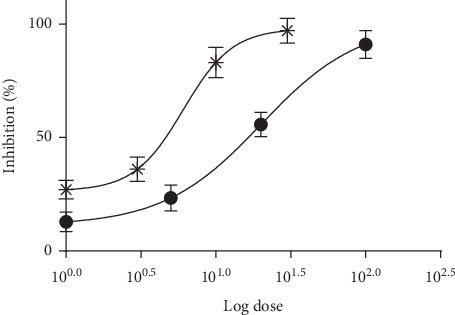

The chemosuppressive antimalarial activity of KMF and ART against PbANKA-infected mice is shown in Figure 1. KMF presented a significant (P < 0.05) dose-dependent inhibition in parasitemia levels with similar inhibition as in ART-treated groups. From the dose-response curve, the ED50 of KMF and ART was 20.06 ± 2.65 and 6.06 ± 1.33 mg/kg, respectively.

Figure 1.

Dose-response curve of antimalarial activity of (∗) ART and (•) KMF against PbANKA-infected mice.

3.2. Combination of KMF and ART against PbANKA-Infected Mice

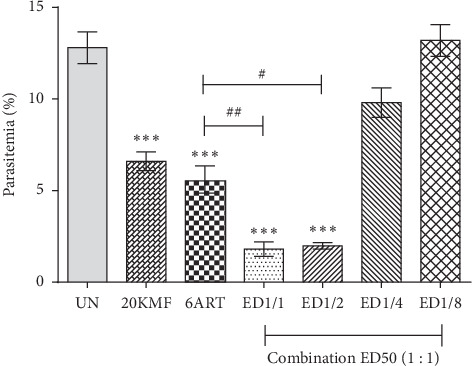

The combination of KMF and ART at the doses of their respective ED50 and fixed-ratio combination (1 : 1) of their respective ED50 of 1/2 exerted a significant (P < 0.001) reduction of parasitemia, compared to the untreated group with the CI values of 0.86 and 0.47, respectively, indicating synergism (Figure 2 and Table 1). Additionally, significant (P < 0.05) inhibition was also observed in these combinations when compared with 6 mg/kg of the ART-treated group. However, the combination of KMF and ART at the doses of their respective at 1/4 ED50 and 1/8 ED50 did not show the significant inhibition as compared to untreated and 6 mg/kg of ART-treated groups with the CI values of 4.64041 and 85.9454, respectively, indicating antagonism (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Antimalarial activity of combination treatment against PbANKA-infected mice. Groups of ICR mice (5 mice of each) were inoculated with 1 × 107 parasitized erythrocytes of PbANKA by IP injection. They were then given the combination drugs of ART and KMF at the doses of their respective ED50 and fixed-ratio combination (1 : 1) of their respective ED50 of 1/2, 1/4, and 1/8. The treatment was carried out once a day for 4-consecutive days (D0–D3). Parasitemia was subsequently estimated on D4. ∗∗∗P < 0.001, compared to the untreated group. #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01, compared to 6ART. UN: untreated group; 20KMF: 20 mg/kg of kaempferol; 6ART: 6 mg/kg of artesunate. Results were shown as mean ± SEM.

Table 1.

Combination index values of the combination of artesunate and kaempferol against Plasmodium berghei ANKA-infected mice.

| Test | Dose (mg/kg) | CI value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMF | ART | |||

| Combination (1 : 1) | ED50 | 20 | 6 | 0.86154a |

| ED50 1/2 | 10 | 3 | 0.46680a | |

| ED50 1/4 | 5 | 1.5 | 4.64041b | |

| ED50 1/8 | 2.5 | 0.75 | 85.9454b | |

aCI < 1; synergism, bCI > 1; antagonism.

3.3. Effect of KMF and ART on MST

From the 4-day suppressive test, 5 (14.4 ± 1.9 days), 20 (22.8 ± 1.9 days), and 100 (33.6 ± 4.0 days) mg/kg of KMF produced significantly (P < 0.05) prolonged MST in a dose-dependent manner compared to the untreated group (8.2 ± 1.9 days). Moreover, combination drugs at the doses of their respective ED50 (51.8 ± 2.2 days) and fixed-ratio combination (1 : 1) of their respective at 1/2 ED50 (43.0 ± 2.1 days) showed significant (P < 0.001) prolonged MST when compared to untreated (8.2 ± 1.9 days) and 10 mg/kg of ART- (28.4 ± 2.9 days) treated groups. However, the MST was not significantly prolonged in the combination of the respective at 1/4 ED50 (9.4 ± 1.7 days) and 1/8 ED50 (9.0 ± 1.6 days) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of combination treatment between artesunate and kaempferol on mean survival time of Plasmodium berghei ANKA-infected mice.

| Test | Dose | MST (days) |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 10 ml/kg | 8.2 ± 1.9 |

|

| ||

| KMF | 1 mg/kg | 10.2 ± 1.3 |

| 5 mg/kg | 14.4 ± 1.9∗ | |

| 20 mg/kg | 22.8 ± 1.9∗∗∗ | |

| 100 mg/kg | 33.6 ± 4.0∗∗∗ | |

|

| ||

| ART | 1 mg/kg | 14.6 ± 1.8∗ |

| 3 mg/kg | 17.6 ± 2.1∗∗∗ | |

| 10 mg/kg | 28.4 ± 2.9∗∗∗ | |

| 30 mg/kg | 51.2 ± 4.1∗∗∗ | |

|

| ||

| Combination (1 : 1) | ED50 (20KMF + 6ART) | 51.8 ± 2.2∗∗∗,a |

| ED50 1/2 (10KMF + 3ART) | 43.0 ± 2.1∗∗∗,a | |

| ED50 1/4 (5KMF + 1.5ART) | 9.4 ± 1.7 | |

| ED50 1/8 (2.5KMF + 0.75ART) | 9.0 ± 1.6 | |

∗∗∗ P < 0.001, compared to the untreated group. aP < 0.001, compared to 10 mg/kg of ART.

4. Discussion

ACT is now the major strategy for malarial treatment due to the high efficacy and low probability of antimalarial drug resistance development [15]. This study focused on the combination of KMF and ART, with the aim of developing a new ACT. Using the chronic toxicity test, KMF in mice has been previously reported to be safe at the dose up to 2,000 mg/kg in mice [10]. Moreover, the susceptibility test in the suppressive model of KMF against PbANKA showed potent antimalarial activity in a dose-dependent manner. Accordingly, this was a basis for the selection of the doses (1, 5, 10, 20, and 100 mg/kg) of KMF for the present ED50 evaluation. KMF exerted a significant (P < 0.05) dose-dependent antimalarial activity with similar inhibition as in ART-treated groups. It was due to the fact that antioxidant and anticancer activities of KMF might be responsible for its antimalarial activity [7, 10, 11]. For our finding, the present study reports for the first time ED50 level of KMF in the antimalarial in vivo model.

The combination treatment (1 : 1) of ED50 values of KMF and ART produced a more significant inhibition in parasitemia compared to the use of only ART. The synergistic effect was pronounced when the KMF and ART were used together at the doses of 1/2 ED50 each. This may be related to a rapid onset of antimalarial activity of KMF in combination with ART. Unfortunately, the mode of action involved in the enhanced antimalarial activity obtained with KMF and ART combinations has not yet been investigated. Further studies should be performed to highlight the mechanisms behind its antimalarial interactions. Additionally, the combination of KMF and ART at the doses of ED50 1/4 and ED50 1/8 displayed antagonistic effect. This could be due to the subtherapeutic doses used.

It has been described that the tested compound that could significantly prolong the MST of infected mice is considered as active [13]. For the result of MST obtained from this study, PbANKA-infected mice treated with KMF, ART, and its combination had significantly longer MST than the untreated group. This might be due to the antimalarial activity of these compounds.

5. Conclusion

From this study, it can be concluded that the combination at a fixed ratio (1 : 1) of KMF and ART exerted potent antimalarial activity with a synergistic effect against PbANKA-infected mice. In addition, significant prolonged MST in PbANKA-infected mice treated with these drugs was also observed. Accordingly, KMF could serve as a potential partner drug that can be combined with ART for the treatment of malarial infection.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to the Research Excellence Center for Innovation and Health Products (RECIHP), Walailak University, for providing laboratory facilities. The authors also acknowledge the extraordinary support given by students of the School of Allied Health Sciences and the staff of the animal research facility of Walailak University. This work was supported by the Institute of Research and Innovation, Walailak University (grant number WU-IRG-62-002), the New Strategic Research (P2P) project, and also partly by Chiang Mai University.

Data Availability

The graphs or figures data used to support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Figshare repository (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7973849).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Ashley E. A., Pyae Phyo A., Woodrow C. J. Malaria. The Lancet. 2018;391(10130):1608–1621. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. World Malaria Report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2019. https://wwwwhoint/publications-detail/world-malaria-report-2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visser B. J., van Vugt M., Grobusch M. P. Malaria: an update on current chemotherapy. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2014;15(15):2219–2254. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.944499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweileh W. M., Al-Jabi S. W., Sawalha A. F., AbuTaha A. S., Zyoud S. H. Bibliometric analysis of worldwide publications on antimalarial drug resistance (2006–2015) Malaria Research and Treatment. 2017;2017:13. doi: 10.1155/2017/6429410.6429410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilley L., Straimer J., Gnädig N. F., Ralph S. A., Fidock D. A. Artemisinin action and resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Trends in Parasitology. 2016;32(9):682–696. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao S. M., Wang M. Y. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: global status and basic research. Chinese Journal of Parasitology & Parasitic Diseases. 2014;32:380–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calderon-Montano J. M., Burgos-Moron E., Perez-Guerrero C., Lopez-Lazaro M. A review on the dietary flavonoid kaempferol. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;11:298–344. doi: 10.2174/138955711795305335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devi K. P., Malar D. S., Nabavi S. F., et al. Kaempferol and inflammation: from chemistry to medicine. Pharmacological Research. 2015;99:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajendran P., Rengarajan T., Nandakumar N., Palaniswami R., Nishigaki Y., Nishigaki I. Kaempferol, a potential cytostatic and cure for inflammatory disorders. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;86:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somsak V., Damkaew A., Onrak P. Antimalarial activity of kaempferol and its combination with chloroquine in Plasmodium berghei infection in mice. Journal of Pathogens. 2018;2018:7. doi: 10.1155/2018/3912090.3912090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barliana M. I., Suradji E. W., Abdulah R., et al. Antiplasmodial properties of kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside isolated from the leaves of Schima wallichii against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Biomedical Reports. 2014;2(4):579–583. doi: 10.3892/br.2014.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters W., Portus J. H., Robinson B. L. The chemotherapy of rodent malaria, XXII. The value of drug-resistant strains of Plasmodium berghei in screening for blood schizontocidal activity. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 1975;69(2):155–171. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1975.11686997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira A. B., Dolabela M. F., Braga F. C., Jácome R. L. R. P., Varotti F. P., Póvoa M. M. Plant-derived antimalarial agents: new leads and efficient phythomedicines. Part I. Alkaloids. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 2009;81(4):715–740. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652009000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roell K. R., Reif D. M., Motsinger-Reif A. A. An introduction to terminology and methodology of chemical synergy-perspectives from across disciplines. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2017;8:p. 158. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whegang Youdom S., Chiabi A., Basco L. K. Monitoring the efficacy and safety of artemisinin-based combination therapies: a review and network meta-analysis of antimalarial therapeutic efficacy trials in Cameroon. Drugs in R&D. 2019;19(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s40268-018-0259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The graphs or figures data used to support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Figshare repository (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7973849).