Abstract

Necrosis targeting and imaging has significant implications for evaluating tumor growth, therapeutic response, and delivery of therapeutics to peri-necrotic tumor zones. Hypericin is a hydrophobic molecule with high necrosis affinity and fluorescence imaging properties. To date, the safe and effective delivery of hypericin to areas of necrosis in vivo remains a challenge due to its incompatible biophysical properties. To address this issue, we have developed a biodegradable nanoparticle (Hyp-NP) for delivery of hypericin to tumors for necrosis targeting and fluorescence imaging. The nanoparticle was developed using methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)- b -poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG-PCL) and hypericin by a modified solvent evaporation technique. The size of Hyp-NP was 19.0±1.8 nm from cryo-TEM and 37.3±0.7 nm from dynamic light scattering analysis with a polydispersity index of 0.15±0.01. The encapsulation efficiency of hypericin was 95.05% w/w by UV-vis absorption. After storage for 30 days, 91.4% hypericin was retained in Hyp-NP with nearly no change in hydrodynamic size, representing nanoparticle stability. In an ovarian cancer cell line, Hyp-NP demonstrated cellular internalization with intracellular cytoplasmic localization and preserved fluorescence and necrosis affinity. In a mouse subcutaneous tumor model, tumor accumulation was noted at 8 h post-injection, with near-complete clearance at 96 h post-injection. Hyp-NP was shown to be tightly localized within necrotic tumor zones. Histologic analysis of harvested organs demonstrated no gross abnormalities, and in vitro, no hemolysis was observed. This proof-of-concept study demonstrates the potential clinical applications of Hyp-NP for necrosis targeting.

Keywords: Nanoparticle, Hypericin, Fluorescence, Necrosis, Tumor

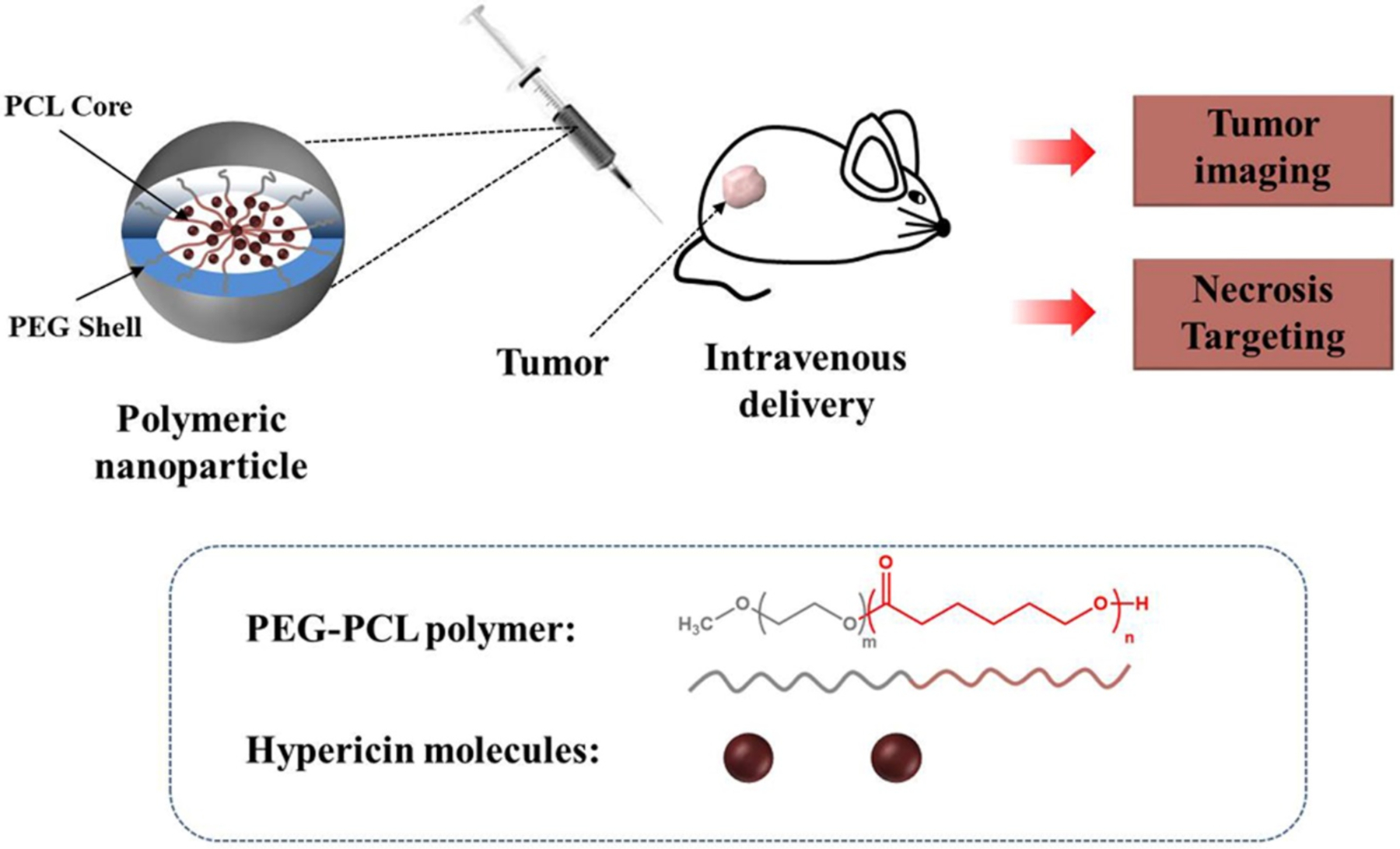

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Necrosis is common in tumor growth and therapeutic response.1 The rapid increase in tumor volume can outpace availability of growth substrates, and cytotoxicity from chemotherapy or ablative therapy can result in necrotic cell death.2 Early detection of necrosis has putative value for assessing aggressive tumor biology and for monitoring therapeutic efficacy.3 Currently, medical imaging can suggest macroscopic necrosis on MRI and contrast-enhanced CT. Clinical assessment of necrosis on the cellular level, however, represents a critical unmet need.

Residual tumor cells surrounding necrotic treatment zones can be a source of tumor recurrence after treatment, such as with thermal ablation.4 Depending on the tumor biology, the time needed for residual tumor cells to result in gross morphological changes detectable by imaging is approximately two to three months.5 Thus, there is an unfulfilled need to identify areas of residual tumor cells after therapy to achieve complete therapeutic response. Based on residual tumor cells localizing to peri-necrotic tumor zones, interest in necrosis-avid agents for delivery of therapeutics has been proposed.6–8

Hypericin, a natural small molecule extracted from Hypericum perforatum, has been studied as a photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy and as an effective agent for necrosis targeted imaging and tumor therapy.6, 8–11 Although the molecular targeting sites of hypericin are still under investigation, applications of hypericin for necrosis-avid contrast agent development and necrosis targeted radiotherapy have increasingly gained attention.12–13 Clinical translation of hypericin to date has been limited by its hydrophobicity, and efforts to address this problem have primarily focused on using organic solvents as carrier media.14–15 Developing an effective hypericin delivery system with a safe therapeutic profile will therefore be of great value.

Herein, we describe the development of a biodegradable nanoparticle for hypericin delivery to necrotic tumor zones. The novel nanostructure is constructed using biodegradable methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG-PCL) to encapsulate hypericin within a hydrophobic PCL core. We examined the nanoparticle’s stability, cellular uptake, hemolysis, cytotoxicity and necrosis affinity using in vitro assays. In vivo, the nanoparticle selectively accumulated in the necrotic tumor zone and demonstrated fluorescence imaging. This nanoplatform may thus represent an effective solution for hypericin delivery for imaging and targeting of therapeutic agents to necrotic tumor zones.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Hypericin with a purity of 98% was purchased from Biopurify Phytochemicals Ltd. (Chendu, China). PEG-PCL (MW = 15000 Da, PDI = 1.15) was obtained from Advanced Polymer Materials Inc. (Montreal, Canada). All other reagents were obtained from Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Fairlawn, USA) and VMR International, LLC (Radnor, USA).

Preparation of hypericin polymeric nanoparticles (Hyp-NP)

Hyp-NP was prepared using a modified solvent evaporation method according to previously published protocol.16–17 Briefly, 20 mg PEG-PCL and 0.4 mg hypericin were dissolved in 2 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF). The solution was transferred into a 20 mL scintillation vial and mixed for 5 min under constant magnetic agitation. Saline (2 mL) was added to the mixed solution. THF was removed under vacuum rotary evaporation at 40 °C. The evaporation process was divided into three segments: the first segment lasting 7 min at 400 mbar, the second segment for 7 min at 320 mbar, and the final segment lasting 2 min at 200 mbar to ensure complete THF removal. The final nanoparticles were obtained after centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 5 min) and filtration using a 0.2 μm filter.

Nanoparticle Characterization and Stability

Nanoparticle morphology and size were assessed by cryo-TEM. 5 μL samples were placed on a 400 mesh copper grid with thin carbon film supported by lacey carbon substrate (Ted Pella 01824), and tested on a Talos Arctica microscope operated at 200 kV. Cryo-TEM images were collected with a defocus range of 2–4 μm. The hydrodynamic diameter, size distribution, and zeta potential of Hyp-NP were determined using dynamic light scattering (DLS, Malvern ZetaSizer NanoSeries, U.K.) at 25 °C according to prior protocol.18–19 All parameters were performed in triplicate to minimize statistical error.

The hypericin loading in the nanoparticle was examined using a UV-1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, CA) according to manufacturer protocol. In order to calculate encapsulation efficiency, 10 μL samples were dried under vacuum conditions, then dissolved in THF to record UV-vis absorption. Hypericin concentration was quantified by UV-vis absorption at 600 nm according to standard calibration curves. The encapsulation efficiency was evaluated as the percentage of hypericin encapsulated in nanoparticles relative to the total initially used for nanoparticle synthesis.

Nanoparticle solutions were kept in a 4 °C refrigerator over a period of thirty days in the dark, and nanoparticle stability was evaluated using the above methods, including assessment of size, surface charge, and hypericin encapsulation. Nanoparticle stability under more physiological conditions was tested in cell culture media. Nanoparticles were incubated with RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine albumin at 37 °C for 72 h. In addition, nanoparticle incubation with rabbit whole blood was conducted to additionally test stability according to previously published protocol.20 At fixed time intervals, the mixed solution was centrifuged (3000 rpm, 5 min) and 100 μL supernatant was used to assess UV-vis absorption. The absorbance of nanoparticle-associated hypericin at 596 nm was recorded for comparison. The time points included the following: immediately, 1 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h after incubation. Nanoparticle degradation was further evaluated by assessing hydrodynamic size and UV-vis absorption changes after incubation with a surfactant of 5 wt% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in PBS for 4 h to imitate cytosolic environment according to previously published protocol.17, 21

Hemolysis evaluation

Red blood cells (RBC) in PBS suspension were prepared to evaluate whether Hyp-NP result in hemolysis. Briefly, swine arterial whole blood (Dotter Interventional Institute, Portland, Oregon, USA) was obtained with EDTA anticoagulation. Blood serum was removed by centrifugation (2000 rpm, 10 min) and RBCs were collected and washed three times with PBS to yield a 2.5% volume of RBC in PBS suspension. 20 μL of cell suspension was incubated with Hyp-NP with concentrations ranging from 100 to 12.5 μg/mL. PBS alone was used as a control. After 3 h incubation at 37 °C, samples were transferred to a hemocytometer to investigate the number of intact red blood cells. All tests were performed in triplicate.

Cytotoxicity evaluation

A Calcein AM cell viability assay (Biotium, Inc., Hayward, CA) was performed to evaluate the potential cytotoxicity of Hyp-NP. A2780N ovarian cancer cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (10000 cells/well) and cultured overnight to allow for cell attachment, then 100 μL Hyp-NP were added to each well with a concentration ranging from 50 to 3.1 μg/mL respectively. Addition of RPMI-1640 medium instead of Hyp-NP was used as a control. After 24 h culture in the dark, cell viability was assessed with Calcein AM solution (10 μM in PBS solution) for 30 min. The fluorescence of each well was recorded by a multi-well Synergy HT plate reader system (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT) with 485/528 nm excitation/emission filters. The cell viability (%) was calculated as a percentage relative to the control. All studies were conducted in 5 parallels.

Cellular uptake

To determine nanoparticle cancer cell internalization, a previously established internalization assay using A2780N ovarian cancer cells was performed.22–23 A2780N cancer cells were cultured in a T25 flask to 40% confluency, followed by 24 h incubation with Hyp-NP (20 μg/mL). Cells were then stained for 30 min with Hoechst 33342 and gently washed with PBS to image viable cell nuclei. Cellular uptake based on intrinsic hypericin fluorescence and co-localization with Hoechst 33342 was assessed using an EVOS FL Cell Imaging System (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) as previously described.24

In vitro cell death assay

The necrosis affinity of Hyp-NP was investigated using an in vitro cell death assay as previously described.25 A2780N cancer cells (20,000 cells/well) were seeded in a 12-well plate and grown to confluency in RPMI-1640 medium. After removing the culture medium, a 1 cm diameter dry ice pellet was applied to the underside of the culture well for 30 seconds to create a cryo-necrotic area. Hyp-NP (50 μg/mL) was then incubated in the culture well for 15 min, and DAPI was incubated for 5 min according to manufacturer protocol to stain nuclei of dead and permeabilized cells. Cells were gently washed with PBS and imaged by EVOS FL Cell Imaging System.

Fluorescence imaging in vivo

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). A nude mouse bearing a subcutaneous tumor of A2780N cancer cells was employed to investigate the localization and fluorescence of Hyp-NP in vivo. The tumor model was developed by injection of A2780N cells (2 × 106) in RPMI medium into the flank of a six-week-old athymic nude mouse (Charles River, Inc.).22 Intrinsic necrosis was developed in the tumors when the largest diameter was greater than 10 mm. An intravenous injection of 0.1 mL Hyp-NP (0.5 mg/kg) was performed via the tail vein. Fluorescence and biodistribution were assessed using the IVIS Lumina XRMS series Ⅲ system (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). The fluorescence excitation/emission wavelengths used were 600 nm and 670 nm, respectively. Observation time points included the following: immediately before injection, and 0.5 h, 2 h, 8 h, 24 h and 96 h after injection.

Necrosis affinity evaluation

To evaluate the in vivo Hyp-NP distribution in tumors, the subcutaneous tumor from the injected mouse was harvested at 8 h post-injection. A 2 mm thick slice was made across the largest part of the tumor to analyze fluorescence using the IVIS system. The tumor was also embedded for cryo-sectioning, and 10 μm slices were sectioned and analyzed for Hyp-NP distribution by fluorescence microscopy (EVOS FL Cell Imaging System). As a control, bis(trihexylsiloxy)silicon 2,3-naphthalocyanine, a hydrophobic NIR fluorescence dye without necrosis avidity,17 was loaded into the same PEG-PCL nanocarrier (NIR-NP) at 1.5mg/kg for intravenous injection using the mouse ovarian tumor model as described in previous protocol.22 The tumor was harvested at 8 h post injection, and also sectioned to analyze fluorescence. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was additionally conducted to identify necrotic regions of tumor.

Safety evaluation in vivo

To evaluate the safety of Hyp-NP in vivo, organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, brain and pancreas were harvested at 8 h post-injection in the treated mouse. The same organs were harvested from a control mouse without Hyp-NP injection for comparison. All organs were embedded in paraffin blocks, and 5 μm slices were sectioned to evaluate histological changes by H&E staining.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using one-way ANOVA. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 20.0 (Chicago, USA). P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Preparation and characterization of Hyp-NP

The schematic illustration of Hyp-NP preparation is shown in Scheme 1. Hydrophobic hypericin was encapsulated in the center of the nanoparticle with an amphiphilic PEG-PCL shell. Morphology from cryo-TEM revealed a uniform spherical shape with a diameter of 19.0±1.8 nm (Figure 1A). Dynamic Light Scattering analysis showed a hydrodynamic size of 37.3±0.7 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.15±0.01, and a zeta potential of −7.5±0.6 mV (Figure 1B). UV-vis spectrophotometry analysis of the nanoparticles revealed an absorption peak of nanoparticle-associated hypericin with 596 nm, and the corresponding peak of free hypericin in THF was 600 nm (Figure 1C). After nanoparticle breakdown in THF, 190.1±0.3 μg/mL hypericin was calculated to be present in the Hyp-NP solution according to calibration curves, translating into a 95.05% Hyp-NP encapsulation efficiency. Nanoparticles remained stable in solution for thirty days, with a similar hydrodynamic size (38.8±0.2 nm) (Figure 1B), polydispersity index (0.19±0.01) and surface charge (−14.3±4.8 mV) as the newly synthesized nanoparticles. The concentration of hypericin in the stored nanoparticle solution was 173.8±0.1 μg/mL, translating to a 8.6% hypericin loss over that time interval. Nanoparticle stability in cell culture medium and in whole blood showed no significant absorbance difference of Hyp-NP comparing that immediately after incubation to that 72 h after incubation, respectively (Figure 1D). After incubation with 5 wt% SDS in PBS, the hydrodynamic size changed greatly from 37.3 nm to 72.0 nm (Figure 1E). The gross view of Hyp-NP also had obvious changes, and UV-vis absorption demonstrated a slight peak shift (~4 nm) after exposure to the 5 wt% SDS in PBS (Figure 1F).

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of Hyp-NP for fluorescence imaging and necrosis targeting. The nanoparticle is constructed by encapsulation of hypericin into PEG-PCL co-polymer. Distribution and metabolism of Hyp-NP can be monitored by fluorescence in vivo, and necrosis affinity can be detected via tumor ex vivo analysis.

Figure 1.

Characterization of Hyp-NP. (A) Morphology by cryo-TEM (Scale bar = 50 nm). (B) Size distribution measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) for nanoparticles immediately after synthesis and after 30 days storage. (C) UV-vis absorption of Hyp-NP and free hypericin after nanoparticle breakdown in THF with a hypericin concentration of 3.8 μg/mL. The inset shows the photo of Hyp-NP solution and its fluorescence image recorded by the Pearl Imaging System at 700 nm. (D) No significant change in absorbance of Hyp-NP at 596 nm is seen either in blood (p=0.67) or RPMI-1640 medium (p=0.70) over time after incubation for 72 h. (E) After incubation with 5 wt% SDS in PBS, nanoparticle size changes are clearly evident by DLS, and the gross appearance of Hyp-NP solution is different with some evidence of breakdown by UV-vis absorption. Inset 1 and 2 are Hyp-NP solution without and with SDS respectively (F).

Hemolysis and cytotoxicity evaluation

Hemolysis evaluation showed nearly all RBCs remained intact for each concentration of Hyp-NP without significant hemolysis (Figure 2A). Calcein AM assay analysis used for cytotoxicity evaluation indicated no cell damage from 3.1 to 12.5 μg/mL hypericin in Hyp-NP, and decrease in cell viability with the increase of hypericin concentration from 25 to 50 μg/mL. This may be due to the cytotoxic and apoptogenic effects of hypericin.26 Cell viability was 81.4±10.2% with a hypericin concentration of 25 μg/mL and 41.5±6.7% with a hypericin concentration of 50 μg/mL (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Safety evaluation in vitro with hemolysis and cytotoxicity evaluation. A: Hemolysis evaluation of Hyp-NP in PBS at increasing concentrations. No significant hemolysis was observed within Hyp-NP from 12.5 to 100 μg/mL. B: Cell viability of A2780N cancer cells incubated with Hyp-NP using increasing hypericin concentration from 3.1 to 50 μg/mL. Significant decrease in cell viability was observed at 50 μg/mL hypericin concentration (*p<0.01).

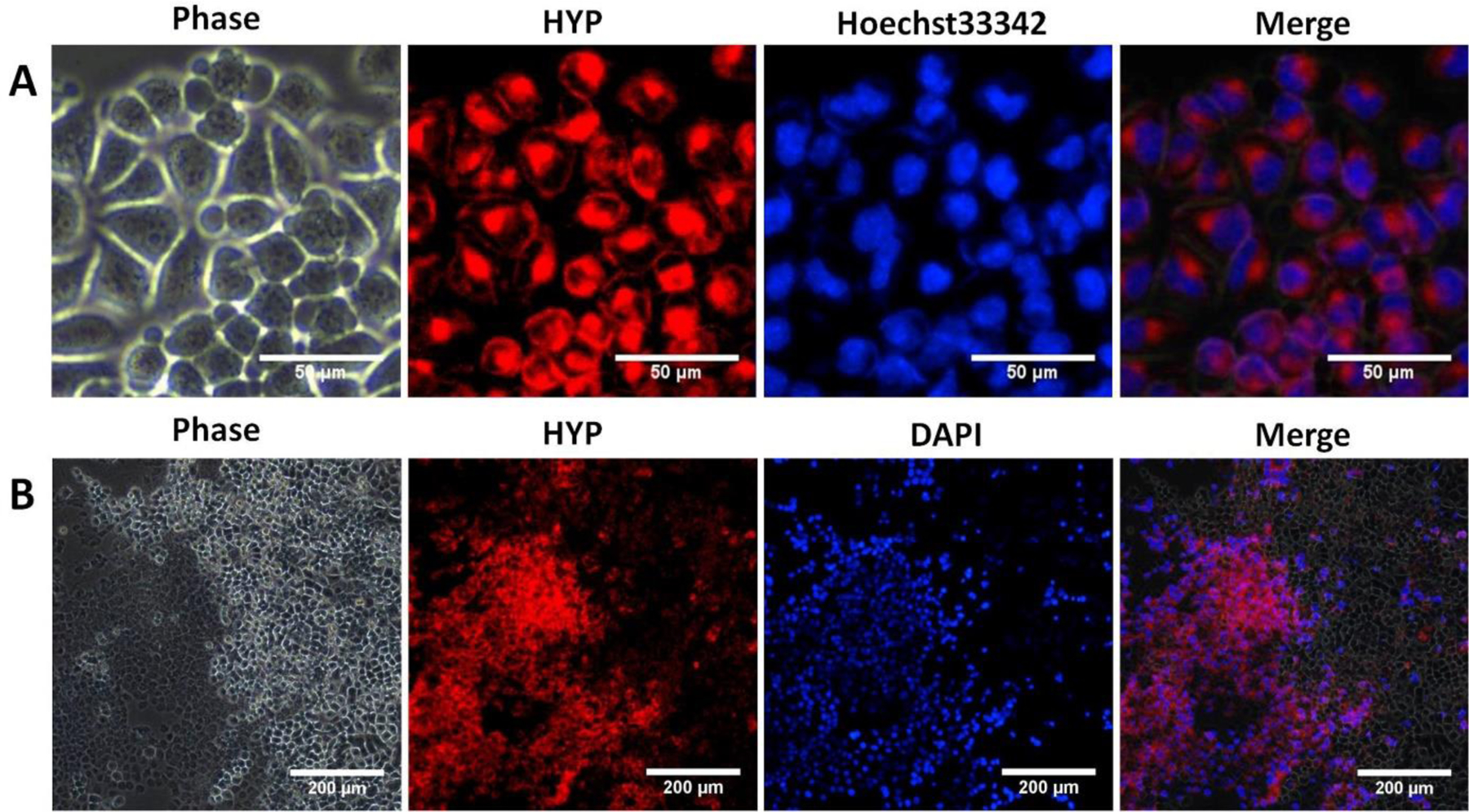

Cellular uptake and in vitro dead cell assay

Cellular uptake of Hyp-NP by A2780N cancer cells was observed under fluorescence microscopy after 24 h incubation. Hyp-NP retained intrinsic hypericin fluorescence, and intracellular nanoparticle localization was observed in the cytoplasm (Figure 3A). The cell death model was induced using lethal freezing temperature with dry ice as previously described.25 Phase-contrast imaging demonstrated the abnormal morphology of cryo-necrotic cells in the left field of view. Positive DAPI (normally impermeable in viable cells) staining identified nuclei from cells with destroyed cell membrane integrity. Hypericin fluorescence co-localized with the dead cells in the cryo-necrotic zone, confirming the preserved necrosis avidity of hypericin delivered with Hyp-NP (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Cellular uptake and necrosis targeting evaluation of Hyp-NP. A: Cellular uptake was evaluated by fluorescence imaging in vitro after incubation with Hyp-NP for 24 h. Hyp-NP retained intrinsic hypericin fluorescence, with intracellular uptake and localization to the cytoplasm. (Scale bar = 50 μm). B: Necrosis affinity evaluation of Hyp-NP using an in vitro cryo-necrosis cell assay. Phase-contrast imaging demonstrated the significant morphological difference between viable cells and dead cells. Hypericin fluorescence co-localized with dead cells (DAPI staining for dead cell nuclei) in the necrotic cell zone. (Scale bar = 200 μm).

Fluorescence imaging in vivo

In order to study the biodistribution of intravenously injected Hyp-NP, a nude mouse bearing a subcutaneous tumor model was employed. Nanoparticle biodistribution at indicated time points after tail vein injection was monitored by IVIS imaging (Figure 4). Hyp-NP gradually accumulated in the tumor, with the highest concentration seen 8 h after intravenous injection. Hyp-NP tumor distribution decreased to baseline levels after 96 h post-injection (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence imaging at different time points after intravenous Hyp-NP injection in a nude mouse bearing a subcutaneous tumor of A2780N cancer cells (N = 1). Fluorescence in tumor (minus background) showed the highest concentration of Hyp-NP 8 h after intravenous injection. The tumor is indicated by the black circle.

Necrosis affinity evaluation ex vivo

Necrosis targeting was evaluated by optical imaging and histological analysis in the explanted tumor from the injected mouse in Figure 4. Hypericin fluorescence co-localized with the dark necrotic zone within the tumor by optical imaging (Figure 5A). Histological analysis showed that hypericin fluorescence from injected Hyp-NP mainly distributed in necrotic areas by fluorescence microscopy and H&E staining, while NIR-NP mainly distributed in the viable tumor zone (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Necrosis affinity evaluation by optical imaging and histological analysis. A: Gross image of a 2 mm thick tumor section (a) and its associated fluorescence (c). The black line delineates areas of necrosis in the tumor section (b). Hyp-NP fluorescence mainly distributed to the necrotic zone (d) and (e). B: Histological analysis of tumor from cryo-sections after intravenous injection of Hyp-NP and compared to NIR-NP, Hyp-NP fluorescence mainly localized to the necrotic zone and NIR-NP to the viable zone. Scale bar = 500 μm.

Safety evaluation in vivo

Safety evaluation in vivo was performed using histological analysis by H&E staining. Heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, brain and pancreas were investigated for differences between the treated and control mice. No significant differences were observed.

DISCUSSION

Precise imaging of tumor necrosis carries the significant potential to evaluate tumor biology and therapeutic response. There has been increasing interest in the development of necrosis-avid agents to image treatment response or target therapeutics to viable tumor cells surrounding necrotic tissue.3, 27 Hypericin is a natural small molecule with strong necrosis targeting capability that has been investigated in previous studies.13, 28–29 However, the hydrophobic property of hypericin and its aggregation in aqueous solution may limit its clinical potential. A highly biocompatible system for safe and effective delivery of hypericin to necrotic tumor sites in vivo remains a significant unmet need. In the present study, we developed a proof-of-concept nanoplatform for hypericin delivery using in vitro and in vivo assays.

PEG and PCL are very safe and biocompatible polymeric materials approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).30–31 Nanoparticles with a PEG- shell are biodegradable, non-toxic and eliminated from the body over time. Moreover, PEG-PCL copolymer can be readily manipulated for self-assembly to form polymeric nanoparticles in aqueous solution.32 Additionally, the amphiphilic property of the PCL layer enables encapsulation and delivery of hydrophobic agents.22, 33 We successfully leveraged these properties to formulate a biocompatible nanoparticle encapsulating hypericin while retaining its absorption and fluorescence properties.

Various nanocarriers have been developed for delivery of imaging agents and therapeutic drugs to tumors.34–37 Size and safety concerns should be considered in detail for potential clinical applications. Nanoparticles with sizes less than 10 nm are rapidly cleared by renal excretion due to the renal average filtration pore of 10 nm, while nanoparticles with sizes over 100 nm may be recognized by macrophages and cleared by the mononuclear phagocyte system.38 Nanoparticle with sizes from 10 to 100 nm have demonstrated enhanced uptake in the abnormal vasculature of tumors.39 The hydrodynamic Hyp-NP size of 37.3 nm is well within the size range known to passively accumulate in tumor tissue through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect and generate a longer circulation time for biological function,38 which may putatively enable greater hypericin localization in necrotic tumor areas. Moreover, the low PDI of less than 0.2 suggests a uniform nanoparticle size distribution, and nanoparticle size and properties remained stable in storage up to thirty days. Furthermore, Hyp-NP nanoparticles were synthesized with high encapsulation efficiency and demonstrated nearly no hemolysis as a delivery vehicle for hypericin. In addition, histological safety evaluation between the treated and control mice demonstrated a safe nanoparticle profile for Hyp-NP, and near-complete clearance from the body by 96 h after intravenous injection.

In vitro, our results showed that nanoparticle-encapsulated hypericin preserved fluorescence and that this nanoplatform efficiently delivered hydrophobic hypericin into A2780N cancer cells. Furthermore, the cryo-necrosis assay in our study demonstrated predominant distribution of hypericin fluorescence to necrotic regions, showing that nanoparticle-encapsulated hypericin retained its notable necrosis targeting traits.40 While intracellular uptake of Hyp-NP in viable cells was noted after 24 h in vitro incubation time, co-localization to necrotic cells was seen within 15 min of incubation, demonstrating its potent necrosis targeting potential.

Surfactants such as SDS have been used to imitate the cytosolic environment in nanoparticle research.21, 41 Hyp-NP incubated in 5 wt% SDS solution nearly doubled the hydrodynamic size of the nanoparticles from 37.3 nm to 72.0 nm, indicating that SDS can disrupt the dense hydrophobic nanoparticle core and expose the internal molecules. Our results showed that, while Hyp-NP was stable in whole blood, changes in size and spectrometry absorbance after adding SDS suggest the potential for biodegradation in cytosol and subsequent nanoparticle content release. Exposure to extracellular cytosolic compounds in necrotic cells, with subsequent nanoparticle degradation and hypericin release, may partially explain how encapsulated hypericin retained its necrosis affinity. In vivo, we observed rapid localization of Hyp-NP fluorescence to necrotic tumor areas within 8 h after intravenous injection. This demonstrated the functional targeting capability of Hyp-NP to necrotic regions within the tumor in vivo, and overall suggests strong clinically translatable potential.

This study has several limitations. First, fluorescence imaging in our study is based on near-infrared light. Near-infrared fluorescence provides the highest spatial resolution for disease diagnosis on a microscopic level. However, the limited penetration depth restricts its clinical applications to subcutaneous, endoscopic and operative exposure.42 Second, Hyp-NP was investigated in vivo using a nude mouse tumor model. More efforts will be needed to show reproducible findings in other biologically relevant models, and to determine whether the signal observed was from intact nanoparticles or free hypericin released from nanoparticles. Moreover, safety evaluation in vivo for a longer survival time will be needed in the future to facilitate clinical translation. Additionally, no tumoricidal or response studies were performed, as this was primarily a proof-of-concept study. Future work looking at the capability of this nanoplatform for drug-delivery and molecular imaging will expand the translational potential for this technology.

CONCLUSIONS

A biodegradable nanoparticle consisting of PEG-PCL with encapsulation of hypericin in the PCL core was developed with necrosis affinity and fluorescence imaging in vitro and in vivo. The novel nanoplatform is safe, stable, and consistent with a rational size for potential applications in tumor imaging and therapy. Future efforts will focus on coupling this technology with additional therapeutic and imaging agents.

Figure 6.

Safety evaluation in vivo by histological analysis. Organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, brain and pancreas demonstrated no significant difference between treated and control mice. (Magnification = ×400).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the Dotter Interventional Institute, Department of Interventional Radiology, Oregon Health and Science University, College of Pharmacy at Oregon State University (OSU), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of NIH (KL2 TR002370) and Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (No. 81630053, 81901846).

ABBREVIATIONS

- PEG-PCL

methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone)

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CT

computed tomography

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention effect

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- RBC

Red blood cells

- PDI

polydispersity index

- NIR

near infrared

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang X; Chen L The recent progress of the mechanism and regulation of tumor necrosis in colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2016, 142 (2), 453–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang D; Gao M; Jin Q; Ni Y; Zhang J Updated developments on molecular imaging and therapeutic strategies directed against necrosis. Acta Pharm Sin B 2019, 9 (3), 455–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang A; Wu T; Bian L; Li P; Liu Q; Zhang D; Jin Q; Zhang J; Huang G; Song S Synthesis and Evaluation of Ga-68-Labeled Rhein for Early Assessment of Treatment-Induced Tumor Necrosis. Mol Imaging Biol 2019, DOI: 10.1007/s11307-019-01365-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrodin S; Lachenmayer A; Maurer M; Kim-Fuchs C; Candinas D; Banz V Percutaneous stereotactic image-guided microwave ablation for malignant liver lesions. Sci Rep 2019, 9 (1), 13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu T; Zhang J; Jin Q; Gao M; Zhang D; Zhang L; Feng Y; Ni Y; Yin Z Rhein-based necrosis-avid MRI contrast agents for early evaluation of tumor response to microwave ablation therapy. Magn Reson Med 2019, 82 (6), 2212–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao L; Zhang J; Ma T; Yao N; Gao M; Shan X; Ni Y; Shao H; Xu K Improved therapeutic outcomes of thermal ablation on rat orthotopic liver allograft sarcoma models by radioiodinated hypericin induced necrosis targeted radiotherapy. Oncotarget 2016, 7 (32), 51450–51461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao H; Zhang J; Sun Z; Chen F; Dai X; Li Y; Ni Y; Xu K Necrosis targeted radiotherapy with iodine-131-labeled hypericin to improve anticancer efficacy of vascular disrupting treatment in rabbit VX2 tumor models. Oncotarget 2015, 6 (16), 14247–14259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J; Sun Z; Zhang J; Shao H; Miranda Cona M; Wang H; Marysael T; Chen F; Prinsen K; Zhou L; Huang D; Nuyts J; Yu J; Meng B; Bormans G; Fang Z; de Witte P; Li Y; Verbruggen A; Wang X; Mortelmans L; Xu K; Marchal G; Ni Y A Dual-targeting Anticancer Approach: Soil and Seed Principle. Radiology 2011, 260 (3), 799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X; Feng Y; Jiang C; Lou B; Li Y; Liu W; Yao N; Gao M; Ji Y; Wang Q; Huang D; Yin Z; Sun Z; Ni Y; Zhang J Radiopharmaceutical evaluation of (131)I-protohypericin as a necrosis avid compound. J Drug Target 2015, 23 (5), 417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi X; Shao H; Zhang J; Sun Z; Ni Y; Xu K Radiopharmaceutical study on Iodine-131-labelled hypericin in a canine model of hepatic RFA-induced coagulative necrosis. Radiol Med 2015, 120 (2), 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahamse H; Hamblin MR New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Biochem J 2016, 473 (4), 347–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonge H; Vunckx K; Wang H; Feng Y; Mortelmans L; Nuyts J; Bormans G; Verbruggen A; Ni Y Non-invasive detection and quantification of acute myocardial infarction in rabbits using mono-[123I]iodohypericin microSPECT. Eur Heart J 2008, 29 (2), 260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van de Putte M; Marysael T; Fonge H; Roskams T; Cona MM; Li J; Bormans G; Verbruggen A; Ni Y; de Witte PA Radiolabeled iodohypericin as tumor necrosis avid tracer: diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Int J Cancer 2012, 131 (2), E129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong M; Zhang J; Jiang C; Jiang X; Li Y; Gao M; Yao N; Huang D; Wang X; Fang Z; Liu W; Sun Z; Ni Y Necrosis affinity evaluation of 131I-hypericin in a rat model of induced necrosis. J Drug Target 2013, 21 (6), 604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abma E; Peremans K; De Vos F; Bosmans T; Kitshoff AM; Daminet S; Ni Y; Dockx R; de Rooster H Biodistribution and tolerance of intravenous iodine-131-labelled hypericin in healthy dogs. Vet Comp Oncol 2018, 16 (3), 318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duong T; Li X; Yang B; Schumann C; Albarqi HA; Taratula O; Taratula O Phototheranostic nanoplatform based on a single cyanine dye for image-guided combinatorial phototherapy. Nanomedicine 2017, 13 (3), 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X; Schumann C; Albarqi HA; Lee CJ; Alani AWG; Bracha S; Milovancev M; Taratula O; Taratula O A Tumor-Activatable Theranostic Nanomedicine Platform for NIR Fluorescence-Guided Surgery and Combinatorial Phototherapy. Theranostics 2018, 8 (3), 767–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taratula O; Patel M; Schumann C; Naleway MA; Pang AJ; He H; Taratula O Phthalocyanine-loaded graphene nanoplatform for imaging-guided combinatorial phototherapy. Int J Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2347–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dani RK; Schumann C; Taratula O; Taratula O Temperature-tunable iron oxide nanoparticles for remote-controlled drug release. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15 (4), 963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aliabadi HM; Brocks DR; Mahdipoor P; Lavasanifar A A novel use of an in vitro method to predict the in vivo stability of block copolymer based nano-containers. J Control Release 2007, 122 (1), 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L; Ma G; Zhang C; Wang H; Sun H; Wang C; Song C; Kong D An Activatable Theranostic Nanomedicine Platform Based on Self-Quenchable Indocyanine Green-Encapsulated Polymeric Micelles. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2016, 12 (6), 1223–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taratula O; Doddapaneni BS; Schumann C; Li X; Bracha S; Milovancev M; Alani AWG; Taratula O Naphthalocyanine-Based Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles for Image-Guided Combinatorial Phototherapy. Chem Mater 2015, 27 (17), 6155–6165. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taratula O; Savla R; He H; Minko T Poly(propyleneimine) dendrimers as potential siRNA delivery nanocarrier: from structure to function. Int J Nanotechnol 2011, 8 (1/2), 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumann C; Chan S; Khalimonchuk O; Khal S; Moskal V; Shah V; Alani AWG; Taratula O; Taratula O Mechanistic Nanotherapeutic Approach Based on siRNA-Mediated DJ-1 Protein Suppression for Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Mol Pharm 2016, 13 (6), 2070–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie BW; Park D; Van Beek ER; Blankevoort V; Orabi Y; Que I; Kaijzel EL; Chan A; Hogg PJ; Lowik CW Optical imaging of cell death in traumatic brain injury using a heat shock protein-90 alkylator. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirmalek SA; Azizi MA; Jangholi E; Yadollah-Damavandi S; Javidi MA; Parsa Y; Parsa T; Salimi-Tabatabaee SA; Ghasemzadeh Kolagar H; Alizadeh-Navaei R Cytotoxic and apoptogenic effect of hypericin, the bioactive component of Hypericum perforatum on the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Cancer Cell Int 2016, 16, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cona MM; Alpizar YA; Li J; Bauwens M; Feng Y; Sun Z; Zhang J; Chen F; Talavera K; de Witte P; Verbruggen A; Oyen R; Ni Y Radioiodinated hypericin: its biodistribution, necrosis avidity and therapeutic efficacy are influenced by formulation. Pharm Res 2014, 31 (2), 278–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jendzelovska Z; Jendzelovsky R; Kucharova B; Fedorocko P Hypericin in the Light and in the Dark: Two Sides of the Same Coin. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ni Y; Huyghe D; Verbeke K; de Witte PA; Nuyts J; Mortelmans L; Chen F; Marchal G; Verbruggen AM; Bormans GM First preclinical evaluation of mono-[123I]iodohypericin as a necrosis-avid tracer agent. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I 2006, 33 (5), 595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Https://www.fda.gov/media/81123/download. 2011July13.

- 31.Https://www.fda.gov/media/95299/download. 2015November9.

- 32.Albarqi HA; Wong LH; Schumann C; Sabei FY; Korzun T; Li X; Hansen MN; Dhagat P; Moses AS; Taratula O; Taratula O Biocompatible Nanoclusters with High Heating Efficiency for Systemically Delivered Magnetic Hyperthermia. ACS Nano 2019, 13 (6), 6383–6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taratula OR; Taratula O; Han X; Jahangiri Y; Tomozawa Y; Horikawa M; Uchida B; Albarqi HA; Schumann C; Bracha S; Korzun T; Farsad K Transarterial Delivery of a Biodegradable Single-Agent Theranostic Nanoprobe for Liver Tumor Imaging and Combinatorial Phototherapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2019, 30 (9), 1480–1486 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santra S; Kaittanis C; Perez JM Cytochrome C encapsulating theranostic nanoparticles: a novel bifunctional system for targeted delivery of therapeutic membrane-impermeable proteins to tumors and imaging of cancer therapy. Mol Pharm 2010, 7 (4), 1209–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taratula O; Schumann C; Naleway MA; Pang AJ; Chon KJ; Taratula O A multifunctional theranostic platform based on phthalocyanine-loaded dendrimer for image-guided drug delivery and photodynamic therapy. Mol Pharm 2013, 10 (10), 3946–3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Min Y; Caster JM; Eblan MJ; Wang AZ Clinical Translation of Nanomedicine. Chem Rev 2015, 115 (19), 11147–11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ventola CL Progress in Nanomedicine: Approved and Investigational Nanodrugs. P T 2017, 42 (12), 742–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han X; Xu K; Taratula O; Farsad K Applications of nanoparticles in biomedical imaging. Nanoscale 2019, 11 (3), 799–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoshyar N; Gray S; Han H; Bao G The effect of nanoparticle size on in vivo pharmacokinetics and cellular interaction. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2016, 11 (6), 673–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Wang; Zhao Saiyin; He Zhao; Li Talebi; Huang Ni. A Model In Vitro Study Using Hypericin: Tumor-Versus Necrosis-Targeting Property and Possible Mechanisms. Biology 2020, 9 (1), 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SJ; Koo H; Lee D-E; Min S; Lee S; Chen X; Choi Y; Leary JF; Park K; Jeong SY; Kwon IC; Kim K; Choi K Tumor-homing photosensitizer-conjugated glycol chitosan nanoparticles for synchronous photodynamic imaging and therapy based on cellular on/off system. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (16), 4021–4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tummers QR; Boogerd LS; de Steur WO; Verbeek FP; Boonstra MC; Handgraaf HJ; Frangioni JV; van de Velde CJ; Hartgrink HH; Vahrmeijer AL Near-infrared fluorescence sentinel lymph node detection in gastric cancer: A pilot study. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22 (13), 3644–3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]