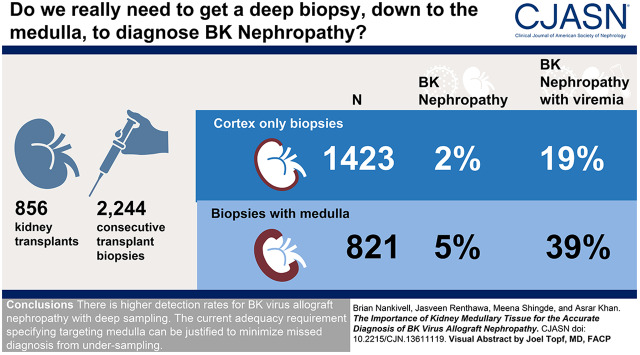

Visual Abstract

Keywords: BK Virus, kidney transplantation, Polyomavirus, immunohistochemistry, Polyomavirus Infections, kidney disease, Transplantation, Biopsy, Virus Replication, Banff schema

Abstract

Background and objectives

The published tissue adequacy requirement of kidney medulla for BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis lacks systematic verification and competes against potential increased procedural risks from deeper sampling.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We evaluated whether the presence of kidney medulla improved the diagnostic rate of BK nephropathy in 2244 consecutive biopsy samples from 856 kidney transplants with detailed histologic and virologic results.

Results

Medulla was present in 821 samples (37%) and correlated with maximal core length (r=0.35; P<0.001). BK virus allograft nephropathy occurred in 74 (3% overall) but increased to 5% (42 of 821) with medulla compared with 2% (32 of 1423) for cortical samples (P<0.001). Biopsy medulla was associated with infection after comprehensive multivariable adjustment of confounders, including core length, glomerular number, and number of cores (adjusted odds ratio, 1.81; 95% confidence interval, 1.02 to 3.21; P=0.04). In viremic cases (n=275), medulla was associated with BK virus nephropathy diagnosis (39% versus 19% for cortex; P<0.001) and tissue polyomavirus load (Banff polyomavirus score 0.64±0.96 versus 0.33±1.00; P=0.006). Biopsy medulla was associated with BK virus allograft nephropathy using generalized estimating equation (odds ratio, 2.04; 95% confidence interval, 1.05 to 3.96; n=275) and propensity matched score comparison (odds ratio, 2.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.11 to 4.54; P=0.03 for 156 balanced pairs). Morphometric evaluation of Simian virus 40 large T immunohistochemistry found maximal infected tubules within the inner cortex and medullary regions (P<0.001 versus outer cortex).

Conclusions

Active BK virus replication concentrated around the corticomedullary junction can explain the higher detection rates for BK virus allograft nephropathy with deep sampling. The current adequacy requirement specifying targeting medulla can be justified to minimize a missed diagnosis from undersampling.

Introduction

BK virus is an endemic human polyoma virus of low morbidity and high seroprevalence rates of 80%–90%. Following childhood infection, BK virus can establish a lifelong asymptomatic infection within the kidney (1). Virus can reactivate following transplantation of a donor kidney (2,3), presenting as asymptomatic viremia from 10% to 30% of screening programs or destructive BK virus allograft nephropathy in 5%–6% of recipients (2,4). BK nephropathy fails 10%–80% of infected kidney transplants. Screening programs detecting early low-level viremia are managed by reduced immunosuppression and often clear following reconstitution of recipient endogenous antiviral cellular immunity (5–10). Patients with high-level viremia (conventionally 1+E104 copies per milliliter) or kidney transplant dysfunction require a biopsy for pathologic diagnosis, risk stratification, and optimal clinical management.

The intrakidney distribution of BK virus is often patchy, especially in early disease. Obtaining an adequate tissue sample in BK infection is important to avoid a false negative diagnosis from undersampling. The Banff Working Group for Polyomavirus Nephropathy (PVN) recommends two biopsy cores containing medulla and immunohistochemistry for Simian virus 40 large T (SV40T) antigen. However, targeting the medulla of the kidney could increase the procedural risks from deeper needle-core biopsy sampling. This theoretical requirement is on the basis of expert opinion and lacks systematic evaluation. The purpose of this study was to determine if the published adequacy requirement for medullary tissue can be justified for the diagnosis of BK virus allograft nephropathy. We evaluated a large prospectively collected dataset with comprehensive biopsy-core information, including presence of medulla and other physical biopsy parameters, histopathology and SV40T immunohistochemistry, circulating viral loads, clinical BK virus risk factors, and demographic information, against a confirmed pathologic diagnosis of BK nephropathy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

The design was a prospective, single-center, observational cohort study. The a priori hypothesis tested was that any kidney medulla within the tissue sample would improve the likelihood of a correct pathologic diagnosis for BK virus allograft nephropathy (the optimal test standard). The primary dataset created in 2012 to manage our increasing BK virus case load was designed to prospectively capture information that would eventually answer that question. This manuscript adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent for biopsy was obtained prior to all tissue sampling. The institutional ethics approvals were HREC 2012/6/6.4(3563) and LNR/12/WMEAD/244 (amendment 1).

Consecutive kidney transplant biopsies processed at Westmead Hospital from May 2012 to December 2018 were screened for overall tissue adequacy and availability of contemporaneous SV40T tissue and BK virus blood results. Cases with incomplete data were excluded (Figure 1). In addition to indication samples, our unit obtains protocol biopsies at implantation and 1, 3, and 12 months post-transplant, with additional samples scheduled in the second to third years (for pancreas-kidney recipients) and following treatment of rejection or BK virus allograft nephropathy. Standard risk immunosuppression comprised basiliximab induction, tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisolone. Antithymocyte induction was reserved for high-immunologic risk recipients. Internal double-J ureteric stents were routinely placed in all kidneys to prevent distal ureteral stricture until removal after 1 month (11). Routine BK viremia screening occurred at 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months post-transplant and with indication biopsy according to consensus recommendations (1,7,12). Screening BK viremia without SV40T was managed by reduced immunosuppression. BK virus allograft nephropathy, verified by histopathology, was treated by conversion of tacrolimus to cyclosporine, mycophenolate to leflunomide, intravenous cidofovir and immunoglobulin, according to pathology, clinical factors and rejection risk, as described(13).

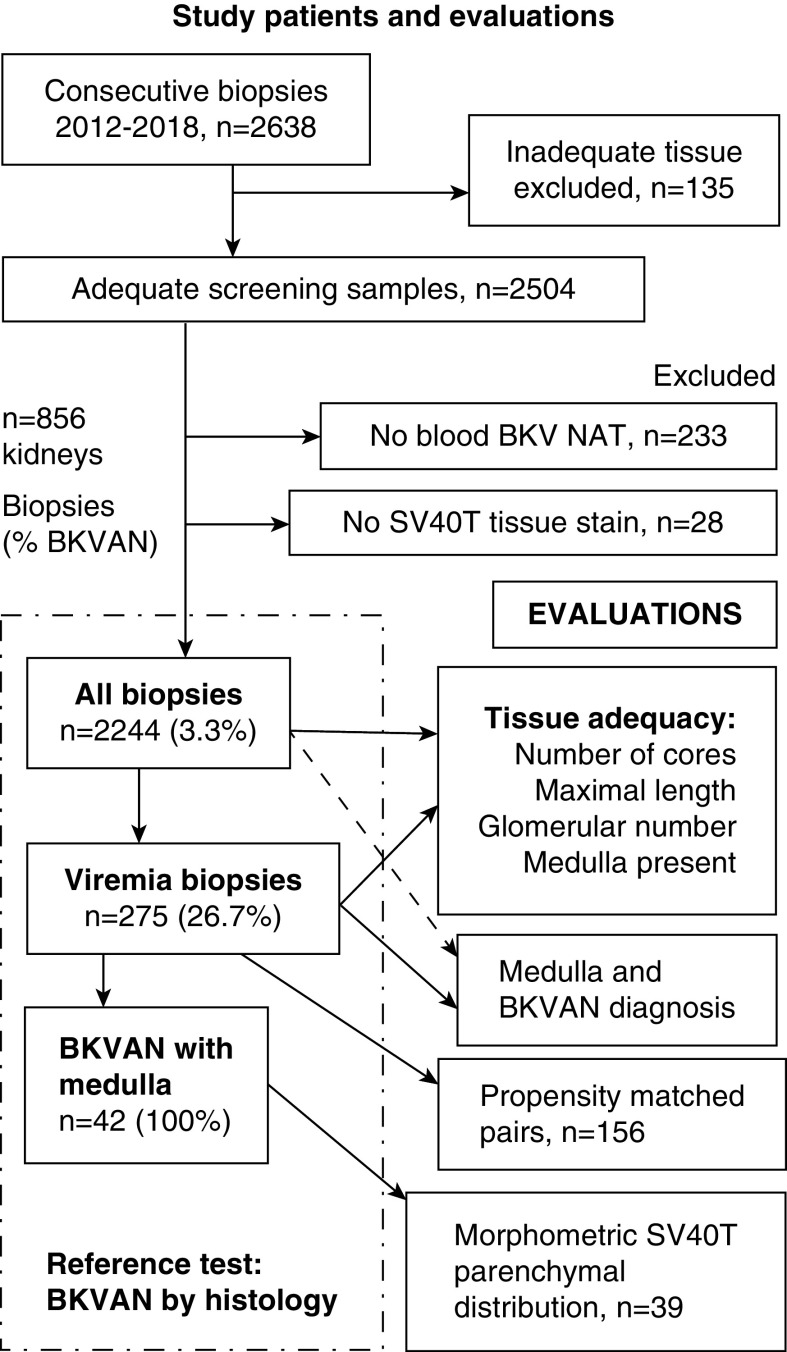

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram of included patients and BK virus investigations. Numbers of included and excluded samples, subcategories of viremic samples, and morphometric analysis (left boxes; total sample numbers are presented with prevalence of BK virus allograft nephropathy [BKVAN] within each subgroup; percentages are in parentheses). Right boxes list study outcome evaluations, population, and subsets. BKV, BK virus; NAT, nucleic acid test; SV40T, Simian virus 40 large T.

Histologic Assessment of BK Virus Allograft Nephropathy and Medulla

The diagnostic reference standard was histologically proven BK virus allograft nephropathy incorporating intranuclear viral inclusions, smudgy nuclear chromatin, cellular atypia, and tubular epithelial cell degeneration with rounding, detachment, or apoptosis (14) and confirmed by SV40T immunohistochemistry (clone MRQ-4; Ventana Benchmark ULTRA using indirect, biotin-free detection; Cell Marque, Tucson, AZ). SV40T antigen expression precedes capsid protein production and intranuclear inclusion body formation, and correspondingly, it detects early disease. Tissue BK virus loads used the semiquantitative Banff cytopathology and SV40T scores (grade 1 =1%; grade 2 =2%–10%; and grade 3 ≥11% infected tubules) and were graded on all included samples (15,16). Histologic abnormalities were assessed by specialist nephropathologists using the Banff schema (17). BK viremia was quantified by specific real-time nucleic acid testing.

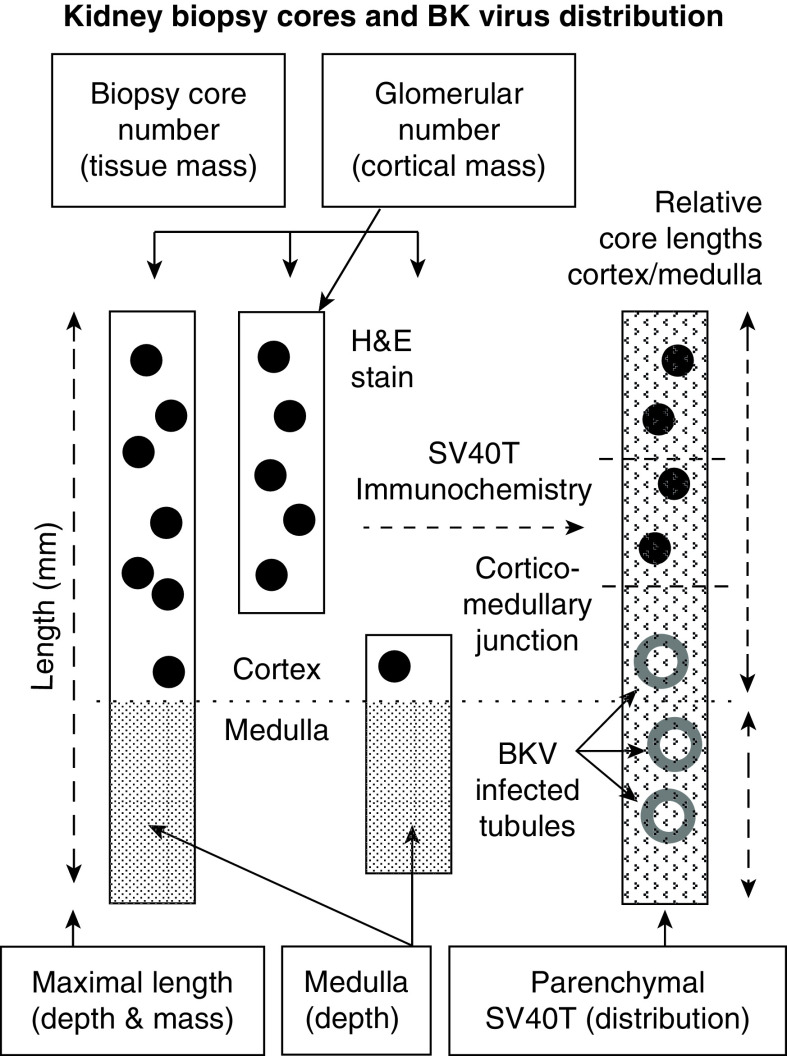

Morphometric analysis of BK virus distribution within kidney parenchyma was additionally undertaken by consensus reporting by two (blinded) nephropathologists (J.R. and M.S.) of adequate samples containing both medulla and cortex. The number of SV40T-positive tubular nuclei within the outer, middle, and inner thirds of kidney cortex, juxtamedullary junction, and medulla were counted at ×20 magnification, and the areal density of positive nuclei per millimeter was calculated. Concentrations of BK virus within medulla and deep kidney cortex were compared with outer cortex as the minimal comparator (illustrated in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Descriptive terminology and illustrated methodology of morphometric analysis for the detection of BK virus. Physical kidney biopsy-core parameters evaluated included samples containing glomeruli (black dots) and/or medulla (shaded) in varying proportions (left three cores). Right kidney core represents the distribution of infected tubular cells in the kidney using SV40T immunohistochemistry of positive tubular cell nuclei within the inner, middle, and outer cortices of the kidney and the medulla as assessed by morphometric analysis. Boxed texts annotate physical attributes of the biopsy core(s) and their corresponding abstract surrogate parameter (parentheses). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical Analyses

The influence of biopsy medulla on the likelihood of BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis was evaluated by (1) conditional binomial exact test for categorical data; (2) univariable and multivariable binomial generalized estimating equation (GEE) for repeated data using medulla as a covariate (controlled for relevant confounder factors, including biopsy length, core, and glomerular number; virologic markers; and other BK risk factors); and (3) a propensity score matched (PSM) comparison. Multivariable models comprehensively adjusted for multiple confounding BK risk factors, including 29 demographic factors, 4 physical biopsy-core parameters, and 18 histopathologic markers (summarized in Supplemental Table 1).

The propensity score was created from multivariable logistic regression using all 19 relevant covariates (known risk factors from expert consensus on significant univariable results). The purpose was to confirm the multivariable model results in case there was residual confounding. The model for β-coefficient values was deliberately nonparsimonious and inclusive and used the viremic subgroup of 275 cases. Nearest neighbor matching was undertaken using the propensity score at the level of the biopsy at 1:1 according to the presence or absence of medulla. We allowed replacement to increase the number of matched pairs. All controls were unique and not double counted. The caliper approximated 0.25 × SEM of propensity scores to verify the range of matching. Unmatched samples were discarded. The initial model was accepted after risk factors were statistically comparable. Propensity scores before and after matching are presented explicitly in data analysis.

An unpaired Student's t-test or Wilcoxon test was used for nominal data, as appropriate. Pearson’s and Spearman’s tests were used for correlation assessments, as appropriate. Data are expressed as mean ± SD unless stated. P values were two sided, and a probability <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Study Clinical Information and Complication Rate

Of 2638 consecutive biopsies screened, samples were excluded because of inadequate tissue (n=135), absent results for viremia (n=233), or SV40T immunohistochemistry (n=28). Evaluable tissue with complete virologic data for 2244 samples was derived from 575 recipients of a kidney (n=1536 samples) and 281 kidney-pancreas transplants (n=708 samples).

The mean recipient age was 47±13 years, 63% were men, HLA mismatch was 3.8±1.7 (of 6), 22% were from living donors, and 7% of biopsies were retransplanted patients (detailed in Table 1, Supplemental Table 2). Induction therapy was basiliximab in 82%, thymoglobulin in 7%, donor-specific antibody or ABO-incompatible desensitization in 0.8%, nil induction in 11%, and unknown in 0.2%. Early acute interstitial, vascular, and C4d-positive antibody rejection occurred in 13%, 1%, and 4%, respectively, and 14% needed dialysis for delayed graft function. At biopsy, prior exposure to thymoglobulin was 16% (7% for induction and 10% rejection), and pulse methylprednisolone was 40% (acute or subclinical rejection treatments). Immunosuppression was tacrolimus (86%) or cyclosporin (11%); azathioprine (4%), mycophenolate (86%), or leflunomine (7% for BK infection); sirolimus/everolimus in 11; and prednisolone in almost all recipients. Daily immunosuppressive doses were 7±5 mg/d for tacrolimus (trough concentrations, 8.9±4.5 ng/ml), 217±113 mg/d for cyclosporin (184±149 ng/ml), 1.81±0.39 g for mycophenolate mofetil, and 14±6 mg/d for prednisolone.

Table 1.

Study patient population

| Transplantation demographic data | Results |

| Recipient age, yr | 47±13 |

| Recipient, men, n (%) | 538 (63) |

| Living donors, n (%) | 191 (22) |

| Donor age, yr | 41±17 |

| Donor, men, n (%) | 457 (53) |

| Any pretransplant DSA, n (%) | 248 (29) |

| Kidney/kidney-pancreas | 575/281 |

| HLA mismatch (of 6) | 3.8±1.7 |

| Causes of end stage kidney failure, n (%) | |

| GN | 251 (29) |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 360 (42) |

| Interstitial nephritis | 6 (0.7) |

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 29 (3) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 66 (8) |

| Reflux dysplastic syndrome | 66 (8) |

| Other or unknown | 78 (9) |

| Early clinical events, n (%) | |

| Delayed graft function | 122 (14) |

| Early acute cellular rejection | 111 (13) |

| Early vascular rejection | 11 (1) |

| Early humoral rejection | 36 (4) |

Summary of demographic data of kidney transplant recipients (856 patients) and early post-transplant events (complete summary of demographic data is in Supplemental Table 2A). Mean ± SD. DSA, donor-specific antibody.

Complications for kidney transplant biopsy (n=355 consecutive audited cases) occurred in three kidneys (0.8%). These included transient gross macroscopic hematuria (n=2, where biopsy samples predominantly consisted of medulla and were admitted overnight) and one perinephric hematoma (patient not admitted, cortical biopsy sample). Overall, 99% of patients were discharged after 4 hours. These audit data were not linked to medullary sampling data and too small to draw meaningful conclusions.

Histopathology and BK Virus Results

Kidney biopsies were obtained at a mean (SD) of 19.3±42.5 months (median, 3; interquartile range, 3–12) after transplantation for an indication in 23% (68% for kidney dysfunction and 18% viremia) or per protocol in 77% (Supplemental Table 2). Samples contained 1.8±0.8 cores, 11±6 glomeruli, and medulla in 37%, and they measured 11.3±4.5 mm in maximal length. The dominant clinicopathologic diagnoses were normal/minor abnormalities in 36%, acute tubular necrosis in 9%, interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in 34%, acute rejection in 6%, subclinical rejection in 5%, chronic rejection in 3%, other diagnoses in 3%, and BK nephropathy in 3% (74 cases). BK virus allograft nephropathy was classified as PVN class 1 in 26 (35%), class 2 in 41 (57%), and late class 3 in 6 (8%) cases (15).

Contemporaneous BK viremia occurred in 13% (275 of 2244) quantified at 2287 copies per milliliter (median; interquartile range, 104–23,319). Blood BK viral loads (loge transformed) correlated with tissue scores for cytopathic polyomavirus (r=0.38; P<0.001) and SV40T (r=0.37; P<0.001), decoy cell number (r=0.32; P<0.001), and BK nephropathy diagnosis (P<0.001). Screening viremia prevalence rates at 1, 3, and 12 months were 2%, 15%, and 12%, respectively. BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis was accompanied by viremia in all patients, except one case of mild resolving infection with a single SV40T-positive tubular cell. Four cases of resolving BK nephropathy with classic cytopathology, viremia, and decoy cell shedding were classified as positive disease despite negative SV40T. Twelve low-level viremic, SV40T-positive BK virus nephropathy cases lacked observed cytopathic effect on histologic sections. One viremic, SV40T-negative case with plasma cell infiltration without cytopathic changes was classified as “negative” by study definition, although clinically treated as presumptive infection.

Determinants of Kidney Medulla in Biopsy Tissue

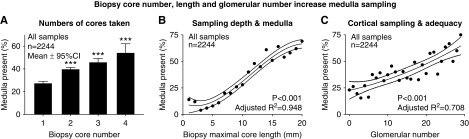

Medulla was present in 37% (821 of 2244) of samples and correlated with maximal core length (r=0.35; P<0.001), glomerular number (r=0.15; P<0.001), and total number of cores obtained (r=0.14; P<0.001) (Figure 3). Medulla sampling was associated with prior and current BK viremia, prior BK nephropathy, indication biopsy, and kidney dysfunction (P=0.002 to P<0.001) (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

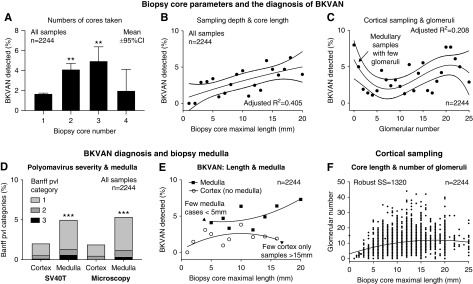

Figure 3.

Medulla was obtained when biopsy cores were longer, more numerous, and contained more glomeruli. Relationships between physical biopsy-core parameters and the probability of obtaining sample medulla. The likelihood of medulla was higher with greater number of cores from the procedure (A), with longer (and deeper) cores reflected by maximal core length (B; P<0.001), and with glomerular numbers (C; reflecting cortical adequacy and overall tissue mass; P<0.001). ***P<0.001 versus single core.

Univariable binomial GEE analysis (n=2244 biopsies from 856 kidneys) found that the presence of medulla was associated with core number (odds ratio [OR], 1.34; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.20 to 1.50; P<0.001), maximal length (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.21; P<0.001; per millimeter), glomerular number (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.07; P<0.001), serum creatinine (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.21; P<0.001; per loge milligrams per deciliter), indication biopsy status (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.66; P=0.003), and prior BK viremia (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.98; P=0.003). Multivariable binomial GEE-confirmed physical biopsy parameters all remained significant when adjusted for viral load and confounding clinical factors (P<0.001) (Table 2; detailed in Supplemental Table 5). Months post-transplant and indication biopsy lost significance as risk factors.

Table 2.

Multivariable associations of medulla on biopsy

| Multivariable Risk Factors | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine, loge mg/dl | 1.21 | 1.00 to 1.46 |

| Prior BK viremia | 1.47 | 1.12 to 1.95 |

| Maximal core length, mm | 1.16 | 1.13 to 1.19 |

| No. of cores | 1.24 | 1.09 to 1.41 |

| Glomeruli, no. | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.04 |

The determinants of sample medulla included all of the physical parameters of the biopsy core using binomial generalized estimating equation to adjust for repeated sampling (n=813 kidneys; estimate of common correlation =0.033) and remained significant despite correction for clinical dysfunction and prior (chronic) viremia, which could prompt increased sampling efforts (compete univariable results and other data are detailed in Supplemental Table 5).

BK Virus Allograft Nephropathy Diagnosis Is Improved with Biopsy Medulla

BK virus allograft nephropathy was diagnosed in 2% of cortical biopsy samples (32 of 1423) compared with 5% containing both cortex and medulla (42 of 821; chi square=13.37; P<0.001). The diagnostic likelihood of disease was higher with multiple cores (versus a single sample), longer cores, and glomerular number (a cortical marker demonstrating a weak and nonlinear relationship, where some medullary samples contained very few glomeruli) (Figure 4, A–C). Biopsy medulla was associated with the greater likelihood of BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis assessed by univariable binomial GEE (OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.05 to 3.96; P=0.03) and remained significant by statistical control of potential BK virus confounders (n=814 kidneys) (Table 3, Supplemental Table 6) using multivariable binomial GEE for repeated sampling analysis. BK tissue infection was also associated with prior (chronic or persistent) BK viremia (versus de novo), circulating viral load, and dysfunction using serum creatinine concentration. Longer biopsy cores containing medulla were associated with higher BK virus detection rates (versus shallow cortical samples; P<0.001) (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Biopsy-core parameters increased the likelihood of BKVAN diagnosis. The likelihood of BKVAN detection was higher with multiple biopsy cores (A) and a longer maximal biopsy core (B; P<0.001). The lesser detection rate with four biopsy cores was explained by multiple shallow cores from difficult cases undergoing additional passes (A). **P<0.01 versus one core. The relationship between glomerular number (cortical adequacy) and BK infection was weaker and nonlinear, where infection could be detected in medullary samples that contained very few glomeruli (C; P<0.001). Glomerular number was associated with longer cores (F). Biopsy polyomavirus (pvl; pvl score category) assessed by SV40T and cytopathologic abnormalities (D; left and right bars, respectively) was also greater when biopsy medulla was present. ***P<0.001 versus cortex. Longer biopsy cores associated with higher BKVAN detection rates; however, samples containing medulla enhanced the diagnostic likelihood compared with cortical samples (E; upper line with black squares and lower line with open circles, respectively; P<0.001 for differences). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; SS, sum of squares.

Table 3.

Multivariable clinicopathologic associations of BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis

| Risk Factors | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Prior BK viremia (any) | 3.91 | 1.88 to 8.14 |

| Viremia, loge+1 copies per milliliter | 1.54 | 1.40 to 1.70 |

| Serum creatinine, loge mg/dl | 3.44 | 1.84 to 6.42 |

| Medulla present | 1.81 | 1.02 to 3.21 |

Pathologically proven tissue infection was more likely found in transplant recipients with prior (chronic/persistent) BK viremia (versus de novo) and in patients with high circulating viral loads (loge-transformed copies per milliliter) or kidney transplant dysfunction (loge-transformed serum creatinine concentration). Medulla included in the biopsy-core sample is also significant using by multivariable binomial generalized estimating equation to control for repeated sampling (n=814 kidneys) (detailed univariable results and other data are in Supplemental Table 6).

A sensitivity subanalysis of 275 BK viremic cases (150 distinct patients) also found that biopsy medulla was associated with greater (1) BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnoses at 39% (43 of 110) versus 19% for cortical samples (31 of 165; chi square=13.83; P<0.001) (Supplemental Table 7) and (2) Banff polyomavirus severity scores (0.64±0.96 versus 0.33±1.00, respectively; P=0.006) (Figure 5A). Multivariable binomial GEE-confirmed medulla was associated with BK virus nephropathy diagnosis when adjusted for multiple clinical and virologic confounders (OR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.36 to 4.62; P=0.003) (Table 4, Supplemental Table 8). Medulla was the only statistically significant parameter of tissue adequacy after control by multivariable regression. Maximal core length lost its significance in favor of biopsy medulla (Figure 4E). Chronic BK viremia, circulating viral loads at biopsy, and indication biopsy status were all associated with the diagnosis of BK virus allograft nephropathy, and serum creatinine was interchangeable with indication biopsy as a risk factor.

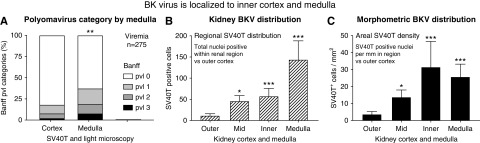

Figure 5.

BK virus localized to the inner cortex and medulla of the transplated kidney. BKV tissue pvl loads in BK viremic samples (n=275) were greater in samples containing medulla versus cortical samples without medulla (A; right and left bars, respectively; scores were derived from the maximal SV40T or cytopathology score). Banff pvl score reflected greater numbers of infected tubules per sample (A). Morphometric analysis of samples containing cortex and medulla (n=39) found that the absolute number of SV40T-positive nuclei (B; expressed as total numbers of cells per region) and the areal density (C; SV40T-positive cells per millimeter2) were greatest in the deep inner cortex (including the corticomedullary junction and the medulla) compared with outer cortex of the kidney. Mean ± SEM. *P=0.05 versus outer cortex; **P=0.01 versus outer cortex; ***P<0.001 versus outer cortex.

Table 4.

Effect of medulla on BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis in viremia

| Multivariable Risk Factors | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Prior BK viremia (any) | 2.35 | 1.19 to 4.65 |

| BK viremia, loge copies per milliliter | 1.23 | 1.08 to 1.40 |

| Indication (versus protocol) | 2.03 | 1.06 to 3.89 |

| Maximal core length, mm | 0.99 | 0.94 to 1.03 |

| Medulla present | 2.51 | 1.36 to 4.62 |

A subgroup sensitivity analysis from viremic cases (n=275 biopsies from 150 patients) used multivariable binomial generalized estimating equations against biopsy-proven BK infection (univariable data are detailed in Supplemental Table 8A). Medulla was the only statistically significant parameter of tissue adequacy remaining after control by multivariable regression. Prior BK viremia indicates persistent (chronic) viremia, and BK viremia reflects current viremia circulating viral load at biopsy (loge transformed). Serum creatinine was interchangeable with indication biopsy as a risk factor.

Propensity score matching using logistic regression of 19 BK virus risk covariates was undertaken in a subset of viremic samples (n=275). Using 1:1 nearest neighbor matching, unmatched samples (32 with medulla and 87 without) were excluded, leaving 156 paired samples balanced for BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis risk factors and biopsy physical parameters (including length, core number, and glomeruli but excluding medulla) (Table 5, Supplemental Table 9) and stratified by medullary sampling. The propensity scores for medulla and control (no medulla) were 0.50±0.20 and 0.32±0.18, respectively, prior to matching (n=275; P<0.001) (Supplemental Table 7A). After PSM, the respective scores were balanced at 0.46±0.20 and 0.43±0.18, respectively (P=0.34) (Table 5, Supplemental Table 9). Within this matched subgroup, BK virus allograft nephropathy was found in 39% of samples containing medulla (versus 22% without; chi square=5.11; P=0.02). The presence of any medulla resulted in a higher diagnostic likelihood for tissue infection (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.11 to 4.54) using logistic regression.

Table 5.

Propensity score matched results from BK viremic recipients (n=156) balanced for selected risk factors (full data are in Supplemental Table 9)

| Factor | Medulla | No Medulla | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopsies, no. | 78 | 78 | |

| Recipient age, yr | 51±14 | 51±13 | 0.94 |

| Recipient, men, n (%) | 58 (74) | 62 (80) | 0.45 |

| Deceased donors, n (%) | 55 (71% | 62 (80) | 0.37 |

| HLA mismatch (of 6) | 3.8±1.7 | 3.9±1.6 | 0.66 |

| Prior corticosteroids (%) | 38 (49% | 38 (49) | 0.99 |

| Months post-transplant | 11.0±14.3 | 11.2±11.6 | 0.93 |

| Indication biopsy, n (%) | 30 (39) | 28 (36) | 0.74 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.88±1.04 | 1.71±0.74 | 0.23 |

| No. of cores | 2.04±0.87 | 1.94±0.73 | 0.43 |

| Maximal core length, mm | 13.0±5.3 | 12.6±5.2 | 0.62 |

| BK median copies | 8.549 | 8.019 | |

| Copies (IQR) | (5.54–10.21) | (4.61–10.84) | 0.70 |

| BKVAN, n (%) | 30 (39) | 17 (22) | 0.02 |

| Propensity score | 0.46±0.20 | 0.43±0.18 | 0.34 |

Mean ± SD. IQR, interquartile range; BKVAN, BK virus allograft nephropathy.

Morphometric Analyses of Viral Distribution in the Kidney

The cortical and medullary distribution of BK virus was further evaluated by morphometric analysis of SV40T-positive nuclei within samples containing both cortex and medulla (n=39). SV40T increased to a maximum at the inner cortex and medulla of the kidney when quantitated by total numbers of positive nuclei (per region) or by areal density of infected cells (per millimeter2). Tissue viral loads were minimal or absent in outer cortex and subcapsular areas (P<0.001; compared with inner cortex and medulla of the kidney) (Figure 5, B and C). Hence, the local concentration of BK virus within medulla and corticomedullary region explained the diagnostic advantage for BK virus nephropathy offered by biopsy samples containing kidney medulla.

Discussion

Adequate tissue sampling is an important determinant of the accuracy of diagnostic pathology of the kidney, especially for diseases with a patchy or focal distribution. For example, a minimum of eight glomeruli from 12 to 15 sections is required for the diagnosis of FSGS (18). In contrast, a single positive glomerulus with mesangial IgA deposition is diagnostically sufficient for IgA nephropathy. For transplant pathology, the Banff consensus recommends a minimal of seven glomeruli and one artery (regarded as “marginal”) from two cores of tissue (17), where adequacy is optimized toward the cortex as the principal location of transplant rejection.

The Banff polyomavirus group also recommends two biopsy cores but additionally stresses the requirement for kidney medulla and SV40T staining for the diagnostic workup of BK infection (15). Undersampling can compromise the diagnosis because early disease is often restricted to a few infected tubules, restricted to a single biopsy core, or confined within the medulla (19). General discordance rates between biopsy cores range between 28.5% and 36.5%, but they are much worse for early disease with patchy viral expression (14,19). The multicenter Banff study (n=192) found BK virus restricted to a single core in 55% of mild PVN class 1 cases (versus 22% for PVN class 2 and 0% for PVN class 3). Infection was missed by microscopy and detected only by SV40T in 48%, underpinning the immunohistochemistry requirement of the guidelines. Virus was limited to medulla in 24% of PVN class 1 (2% of PVN class 2 and 0% of PVN class 3) (15). Another cohort study (n=53) found infection restricted to medulla in 9.4%, in cortex alone in 20.8%, and involving cortex and medulla in 69.8% (14).

As with any patchy disease processes, the simple rule of diagnostic adequacy of “more is better” similarly applies to BK virus allograft nephropathy. All principal biopsy-core physical parameters correlated with its diagnosis, including maximal core length (reflecting biopsy depth and tissue mass), total number of glomeruli (a surrogate for cortical mass), number of cores obtained per procedure (a distributive and tissue mass indicator), and medulla within the tissue sample (reflecting deeper sampling depth). However, our study could specifically attribute the diagnostic advantage to medulla using multivariable analysis (with extensive covariate adjustment) and PSM comparison, besting all other surrogate markers of tissue mass. Those adjusted ORs for medulla and BK virus allograft nephropathy diagnosis were 2.51 and 2.24, respectively, for the viremic subgroup. Hence, although longer biopsy cores were associated with BK virus nephropathy, this relationship was driven by the likelihood of medullary tissue being obtained from deeper samples (Figure 4E).

These results that medullary sampling doubled the diagnostic return support the recommendation of the pathology expert group but pose a dilemma for the transplant clinician at the bedside: deeper needle-core sampling could increase the procedural risk of injury to the adjacent pelvicalyceal system and larger arteries (causing macroscopic hematuria or traumatic arteriovenous malformation, respectively). Clinical judgement and operational expertise determine an individual’s relative risk/benefit and should guide the clinical approach. Our unit’s biopsies are performed by experienced transplant nephrologists or senior registrars, and they are not outsourced to interventional radiology. We use an automated biopsy gun guided by real-time ultrasound. Deep cores targeting medulla can be obtained from cortex overlying a kidney pyramid by directing the line of biopsy away from any visualized minor calyces to minimize the risk of urinary perforation. The biopsy needle should be positioned at the capsule (verified by visual guidance using calibrated imaging markers against their corresponding depth markers) and then deployed (“on touch” or just back from visualized capsular indent) with a 1.5-cm preset needle excursion—therefore, any “overthrow” remains within kidney tissue (i.e., between major calyces). We aim for three good tissue cores in patients with high-level viremia and/or transplant dysfunction.

The strengths of this study included its large unselected population-based cohort derived from diverse “real-world” clinical situations: all verified by consensus histopathology and routine contemporaneous SV40T immunohistochemistry—the optimal test reference standard. Routine SV40T use detects mild PVN class 1 disease (when viral inclusion bodies are absent; 35% in this study and 48% in the multicenter Banff study) (15) and avoids false negative results (i.e., histopathology-negative cases with SV40T occurred in 4% of viremic cases) that could compromise the study reference test validity. Experimental models demonstrate that early BK virus reactivation begins with focal “nonlytic” viral replication accompanied by inconspicuous tubular basement membrane denudation within clusters of medullary tubular epithelial cells. Our case mix of disease severity (PVN class 1, 35%; PVN class 2, 57%; and PVN class 3, 8%) was comparable with international experiences (PVN class 1, 24.7%; PVN class 2, 62.9%; and PVN class 3, 12.4%) (15). The availability of detailed clinical and virologic data allowed for comprehensive adjustment of relevant confounding factors. However, our audited complication rate for kidney transplant biopsy of 0.8% was too small to prove a meaningful correlation about medullary sampling and bleeding (and not designed to test this hypothesis).

In summary, the presence of any kidney medulla within tissue samples approximately doubled the diagnostic likelihood of BK virus allograft nephropathy for viremic transplant recipients. The pathophysiologic explanation from SV40T morphometric substudy was that replicating BK virus was concentrated around the deep corticomedullary junction. Biopsy medulla was the crucial diagnostic parameter and superior to other tissue mass markers, including core length, number of cores obtained, and glomerular number, using both adjusted multivariable analysis and PSM comparisons.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Extensive study data and results are presented within Supplemental Tables 1– 9. These contain 21 highly detailed tables of deidentified summated clinical data with their univariable and multivariable statistical analyses to allow open scientific scrutiny. Federal privacy laws and local institutional ethics forbid the placement of confidential individual patient information onto any public data-sharing website and do not allow for its unauthorized sharing. Specific questions of clinical science can be directed to the corresponding author if not found in Supplemental Tables 1– 9.

Dr. Jasveeen Renthawa and Dr. Meena Shingde were responsible for pathology and morphometric scoring; Dr. Asrar Khan was responsible for the biopsy complication audit data; Dr. Brian Nankivell was responsible for data analysis and research design; and Dr. Asrar Khan, Dr. Brian Nankivell, Dr. Jasveeen Renthawa, and Dr. Meena Shingde participated in paper writing.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13611119/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Confirmed, possible, and speculative risk factors for BK virus infection and/or BK virus allograft nephropathy published in the medical literature used within the multivariable analysis to adjust for potential confounders.

Supplemental Table 2. Complete summary of demographic data.

Supplemental Table 3. Relationships of biopsy physical parameters in the kidney.

Supplemental Table 4. Determinants of medulla on biopsy sample.

Supplemental Table 5. Determinants of biopsy medulla.

Supplemental Table 6. Determinants of biopsy-proven BK virus allograft nephropathy.

Supplemental Table 7. Sensitivity analysis I: evaluation of the subset of samples from BK viremic kidneys (n=275) stratified by medulla within the biopsy core.

Supplemental Table 8. Viremia sensitivity subset analysis II: selected univariable and multivariable determinants of biopsy-proven BK virus allograft nephropathy using binomial generalized estimating equations (n=275 biopsies from 150 kidneys with BK viremia).

Supplemental Table 9. Sensitivity analysis III: propensity matched score results from BK viremic recipients (n=156) balanced for all BK risk factors and stratified for medulla within the biopsy core.

References

- 1.Hirsch HH, Brennan DC, Drachenberg CB, Ginevri F, Gordon J, Limaye AP, Mihatsch MJ, Nickeleit V, Ramos E, Randhawa P, Shapiro R, Steiger J, Suthanthiran M, Trofe J: Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy in renal transplantation: Interdisciplinary analyses and recommendations. Transplantation 79: 1277–1286, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston O, Jaswal D, Gill JS, Doucette S, Fergusson DA, Knoll GA: Treatment of polyomavirus infection in kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review. Transplantation 89: 1057–1070, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirsch HH, Steiger J: Polyomavirus BK. Lancet Infect Dis 3: 611–623, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickeleit V, Singh HK, Mihatsch MJ: Polyomavirus nephropathy: Morphology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12: 599–605, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan DC, Agha I, Bohl DL, Schnitzler MA, Hardinger KL, Lockwood M, Torrence S, Schuessler R, Roby T, Gaudreault-Keener M, Storch GA: Incidence of BK with tacrolimus versus cyclosporine and impact of preemptive immunosuppression reduction. Am J Transplant 5: 582–594, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardinger KL, Koch MJ, Bohl DJ, Storch GA, Brennan DC: BK-virus and the impact of pre-emptive immunosuppression reduction: 5-Year results. Am J Transplant 10: 407–415, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch HH, Randhawa P; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice : BK polyomavirus in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 13[Suppl 4]: 179–188, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuypers DR: Management of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy in renal transplant recipients. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 390–402, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaub S, Hirsch HH, Dickenmann M, Steiger J, Mihatsch MJ, Hopfer H, Mayr M: Reducing immunosuppression preserves allograft function in presumptive and definitive polyomavirus-associated nephropathy. Am J Transplant 10: 2615–2623, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadei HM, Rule AD, Lewin M, Mahale AS, Khamash HA, Schwab TR, Gloor JM, Textor SC, Fidler ME, Lager DJ, Larson TS, Stegall MD, Cosio FG, Griffin MD: Kidney transplant function and histological clearance of virus following diagnosis of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy (PVAN). Am J Transplant 6: 1025–1032, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pleass HC, Clark KR, Rigg KM, Reddy KS, Forsythe JL, Proud G, Taylor RM: Urologic complications after renal transplantation: A prospective randomized trial comparing different techniques of ureteric anastomosis and the use of prophylactic ureteric stents. Transplant Proc 27: 1091–1092, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasiske BL, Zeier MG, Chapman JR, Craig JC, Ekberg H, Garvey CA, Green MD, Jha V, Josephson MA, Kiberd BA, Kreis HA, McDonald RA, Newmann JM, Obrador GT, Vincenti FG, Cheung M, Earley A, Raman G, Abariga S, Wagner M, Balk EM; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients: A summary. Kidney Int 77: 299–311, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kable K, Davies CD, O’connell PJ, Chapman JR, Nankivell BJ: Clearance of BK virus nephropathy by combination antiviral therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin. Transplant Direct 3: e142, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drachenberg CB, Papadimitriou JC, Hirsch HH, Wali R, Crowder C, Nogueira J, Cangro CB, Mendley S, Mian A, Ramos E: Histological patterns of polyomavirus nephropathy: Correlation with graft outcome and viral load. Am J Transplant 4: 2082–2092, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickeleit V, Singh HK, Randhawa P, Drachenberg CB, Bhatnagar R, Bracamonte E, Chang A, Chon WJ, Dadhania D, Davis VG, Hopfer H, Mihatsch MJ, Papadimitriou JC, Schaub S, Stokes MB, Tungekar MF, Seshan SV; Banff Working Group on Polyomavirus Nephropathy : The Banff working group classification of definitive polyomavirus nephropathy: Morphologic definitions and clinical correlations. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 680–693, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sar A, Worawichawong S, Benediktsson H, Zhang J, Yilmaz S, Trpkov K: Interobserver agreement for Polyomavirus nephropathy grading in renal allografts using the working proposal from the 10th Banff Conference on Allograft Pathology. Hum Pathol 42: 2018–2024, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas M, Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, Roufosse C, Glotz D, Seron D, Nankivell BJ, Halloran PF, Colvin RB, Akalin E, Alachkar N, Bagnasco S, Bouatou Y, Becker JU, Cornell LD, van Huyen JPD, Gibson IW, Kraus ES, Mannon RB, Naesens M, Nickeleit V, Nickerson P, Segev DL, Singh HK, Stegall M, Randhawa P, Racusen L, Solez K, Mengel M: The Banff 2017 Kidney Meeting Report: Revised diagnostic criteria for chronic active T cell-mediated rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, and prospects for integrative endpoints for next-generation clinical trials. Am J Transplant 18: 293–307, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuiano G, Comi N, Magri P, Sepe V, Balletta MM, Esposito C, Uccello F, Dal Canton A, Conte G: Serial morphometric analysis of sclerotic lesions in primary “focal” segmental glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 49–55, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickeleit V, Mihatsch MJ: Polyomavirus nephropathy in native kidneys and renal allografts: An update on an escalating threat. Transpl Int 19: 960–973, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.