Visual Abstract

Keywords: regret; shared dialysis decision-making; decisional regret; aged; living wills; logistic models; life expectancy; renal dialysis; prognosis; terminal care; odds ratio; surveys and questionnaires; decision making; renal insufficiency, chronic; emotions; marital status; attitude

Abstract

Background and objectives

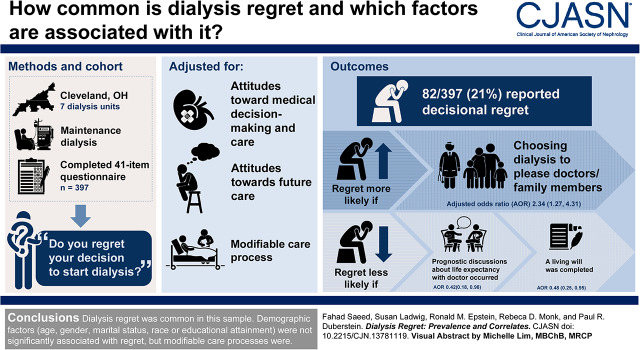

Although some patients regret the decision to start dialysis, modifiable factors associated with regret have rarely been studied. We aimed to identify factors associated with patients’ regret to initiate dialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A 41-item questionnaire was administered to adult patients receiving maintenance dialysis in seven dialysis units located in Cleveland, Ohio, and its suburbs. Of the 450 patients asked to participate in the study, 423 agreed and 397 provided data on decisional regret. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify predictors of regret, which was assessed using a single item, “Do you regret your decision to start dialysis?” We report adjusted odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the following candidate predictors: knowledge of CKD, attitudes toward CKD treatment, and preference for end-of-life care.

Results

Eighty-two of 397 respondents (21%) reported decisional regret. There were no significant demographic correlates of regret. Regret was more common when patients reported choosing dialysis to please doctors or family members (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.27 to 4.31; P<0.001). Patients who reported having a prognostic discussion about life expectancy with their doctors (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.98; P=0.03) and those who had completed a living will (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.95; P=0.03) were less likely to report regret with dialysis initiation.

Conclusions

Dialysis regret was common in this sample. Demographic factors (age, sex, marital status, race, or educational attainment) were not significantly associated with regret, but modifiable care processes were.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2020_06_09_CJN13781119.mp3

Introduction

Regret after dialysis initiation is reported by some patients with kidney failure (1,2). Understanding the factors associated with regret can lead to improvements in the quality of dialysis decision making (1–3). Regret can be experienced after patients reflect on a medical decision, the decision-making process that occurred, and the outcomes of that decision (e.g., effect on quality of life) (3). Hence, the presence or absence of regret is a surrogate marker for the quality of the dialysis decision-making process (4). Mitigation of regret is an important component of dialysis decision making that can be achieved through shared decision making, which includes discussing prognosis (life expectancy and effect of dialysis on emotional and physical well being), weighing pros and cons of treatment options with patients and their family members, and incorporating their preferences into the decision-making process (5). Despite the importance of regret as a measure of the quality of the dialysis decision-making process, few studies have examined regret after dialysis initiation.

In a study of mostly white Canadian patients (80%) with CKD, 61% reported regret with the decision to start dialysis (1). In a study from the United States, again of mostly white patients, the prevalence of regret was only about 7% (6). Reasons for the discrepancy in the prevalence of regret (61% versus 7%) are unknown, and neither study analyzed predictors of regret with dialysis initiation (1,6). Such data were reported by researchers in the Netherlands and Singapore, where the prevalence of regret was 7%–8% (7,8). In the Dutch study, patients starting dialysis on the basis of a nephrologist’s opinion or family preferences were more likely to experience decisional regret (7). In the study from Singapore, regret was associated with greater decisional uncertainty and poor dialysis education (8). Differences in demographics and CKD education programs in the Netherlands and Singapore preclude generalizability of results to patients in the United States, and we are aware of no United States–based studies of predictors of regret with dialysis initiation decisions. Moreover, racial differences exist in patient–physician communication and level of engagement in decision making; these differences potentially predispose black patients to higher regret with dialysis decision making (9,10). Therefore, it is critical to study this issue in a racially diverse cohort of patients. To address this gap in the literature, we examined predictors of regret in a racially diverse cohort of patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

Materials and Methods

We report secondary analyses of data collected in a study on patients receiving maintenance dialysis and their perceptions of dialysis decision making and end-of-life care preferences. Data were collected from November 2014 to December 2014 (2). A 41-item survey was administered to adult patients receiving maintenance dialysis from seven dialysis units in the Cleveland, Ohio area. Patients lacking capacity, as assessed by the physician facilitator, and those unable to speak English were excluded. In addition to explaining the purpose of the study and administering the survey to patients, the facilitator orally administered the surveys to patients with vision issues or those who requested personal assistance with the survey. The facilitator was also available to explain questions that were not clear to patients. Survey items focused on demographics, as well as attitudes and beliefs about dialysis decision making and end-of-life care (2). To assess decisional regret, we asked a single question “Do you regret your decision to start dialysis?” Response options were (1) “Yes,” (2) “No,” (3) and “Don’t know/not sure.” This question has been used to assess regret with dialysis initiation (1,2). Only two respondents did not know or were not sure if they regretted their dialysis decision, and they were included in the “Yes, I regret my decision” category for these analyses because they did not unequivocally respond that there was no regret. On the basis of a review of the literature, candidate predictors of regret were (1) patient demographics (age, sex, race, education level), (2) patient attitudes toward medical decision making and care (assessed the process of dialysis decision making and importance of knowing detailed medical information), (3) patient attitudes toward future care (assessed current self-reported knowledge of kidney disease and its future trajectory, importance of quality of life in determining the future care, thoughts about importance of knowing prognosis and previous prognostic discussions, and the importance of planning for death), and (4) modifiable care process (assessed previous advance care planning) (7,8,11). All of these items (Table 1) were adapted from a previous study (7). The Cleveland Clinic Institutional Board Review approved the study.

Table 1.

Bivariate analyses of selected demographic and potential predictor variables

| Characteristics and Questions | If You Are Currently Receiving Dialysis, Do You Regret the Decision to Start Dialysis? n (%) | Unadjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Dialysis cohort, N=397 | 82 (21) | 315 (79) | ||

| Race | 1.87 (1.02 to 3.44) | 0.04 | ||

| White (ref) | 15 (18) | 93 (30) | ||

| Nonwhite | 67 (82) | 222 (70) | ||

| Mode of dialysis | 1.54 (0.53 to 4.47) | 0.42 | ||

| Hemodialysis (ref) | 73 (94) | 293 (96) | ||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 5 (6) | 13 (4) | ||

| Sex | 0.73 (0.44 to 1.21) | 0.22 | ||

| Female (ref) | 30 (63) | 139 (56) | ||

| Male | 52 (37) | 176 (44) | ||

| Marital status | 0.88 (0.67 to 1.15) | 0.34 | ||

| Married (ref) | 35 (43) | 118 (37) | ||

| Not married | 46 (57) | 197 (63) | ||

| Mean age at first encounter (range) | 59.7 (21–88) | 59.1 (22–91) | 1.003 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.73 |

| Length of time in months on dialysis (range) | 41.5 (2–224) | 52.7 (1–336) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.11 |

| Attitudes toward medical decision making and care | ||||

| How important is to you for your family to be actively involved in medical decision making? | 0.41 (0.24 to 0.70) | <0.001 | ||

| Unsure/unimportant (ref) | 30 (33) | 60 (67) | ||

| Important | 52 (17) | 253 (83) | ||

| If you are currently receiving dialysis, why did you choose dialysis over conservative care? | 2.62 (1.47 to 4.67) | <0.001 | ||

| Doctor’s/family’ s wish (ref) | 63 (78) | 176 (57) | ||

| Personal wish | 18 (22) | 133 (43) | ||

| How important is it for you to be informed about treatment options such as withdrawing dialysis? | 0.02 | |||

| Unsure/unimportant (ref) | 36 (44) | 108 (34) | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.96) | |

| Important | 46 (56) | 206 (66) | ||

| How important is detailed information about your medical condition? | 0.40 (0.23 to 0.71) | 0.001 | ||

| Unsure/unimportant (ref) | 24 (29) | 45 (14) | ||

| Important | 58 (71) | 270 (86) | ||

| Attitudes toward future care | ||||

| How informed are you about your medical condition and how it will change over time? | 0.69 (0.42 to 1.12) | 0.13 | ||

| Uninformed/unsure (ref) | 43 (52) | 136 (43) | ||

| Informed | 39 (48) | 179 (57) | ||

| Have you thought about what might happen with your illness in the future? | 1.37 (0.79 to 2.38) | 0.26 | ||

| No (ref) | 21 (26) | 100 (32) | ||

| Yes | 61 (74) | 212 (68) | ||

| How do you see your health in next 12 mo? | 1.27 (0.67 to 2.84) | 0.56 | ||

| No change/improving (ref) | 74 (90) | 277 (88) | ||

| Worsening | 8 (10) | 38 (12) | ||

| How important is it for your “quality of life” to affect your future care? | 0.42 (0.24 to 0.76) | 0.003 | ||

| Unsure/unimportant (ref) | 22 (27) | 42 (13) | ||

| Important | 60 (73) | 271 (87) | ||

| How important is it for you to be informed about your prognosis? | 0.51 (0.29 to 0.89) | 0.02 | ||

| Unsure/unimportant (ref) | 24 (29) | 55 (17) | ||

| Important | 58 (71) | 260 (83) | ||

| Has your doctor talked to you about how much time you have to live? | 0.44 (0.22 to 0.88 | 0.008 | ||

| No (ref) | 66 (83) | 282 (92) | ||

| Yes | 14 (17) | 26 (8) | ||

| How important is it for you to prepare and plan ahead in case of death? | 0.39 (0.23 to 0.66) | <0.001 | ||

| Unsure/unimportant (ref) | 32 (39) | 63 (20) | ||

| Important | 50 (61) | 250 (80) | ||

| Modifiable care process | ||||

| Have you completed a living will? | 0.51 (0.29 to 0.89) | 0.01 | ||

| No (ref) | 61 (75) | 190 (61) | ||

| Yes | 20 (25) | 122 (39) | ||

| Personal directive | 0.99 (0.53 to 1.83) | 0.98 | ||

| No (ref) | 66 (80) | 254 (81) | ||

| Yes | 16 (20) | 61 (19) | ||

| Health care proxy | 0.79 (0.53 to 1.76) | 0.56 | ||

| No (ref) | 74 (90) | 277 (88) | ||

| Yes | 8 (10) | 38 (12) | ||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ref, reference group.

Statistical Analyses

We used SAS version 9.4 to conduct statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics for all of the study variables were first examined, followed by bivariate analyses assessing crude associations between potential candidate predictors and the dichotomous outcome variable (regret: yes or no). We also examined correlations between candidate predictors to detect potential confounders (not shown), and ran separate stepwise-adjusted models eliminating confounding items from the final model. Missing observations (n=18) were imputed over three iterations for the final adjusted model, using the fully efficient fractional imputation method available in the SURVEYIMPUTE procedure (SAS/STAT version 9.4), in which multiple observations contribute to the replacement of the missing value, and minimize additional variability. The total number for the multivariable model is 397, including the imputed values for the 18 missing observations.

Finally, statistically significant (P≤0.05) variables from the bivariate analyses and logically important predictors, including duration of dialysis and patient age and sex, were then entered into a multivariable logistic regression model. We report adjusted odd ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

Results

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 2. We approached 450 patients receiving maintenance dialysis with capacity to consent, and 423 patients participated (94% response rate). Of the 397 patients who responded to the regret item, 82 patients (21%) reported feeling some regret about dialysis initiation. Table 1 reports the results of the bivariate analyses for demographic characteristics and potentially important predictors of regret.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of respondents

| Data Collection Period | November–December 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | Prospective cohort | |

| Setting | Seven dialysis units in Cleveland, Ohio | |

| Inclusion criteria | Adult English-speaking patients on maintenance dialysis seen in clinic | |

| N (%), unless otherwise specified | Missing, n | |

| All patients who answered the “regret question” | 397 (100) | 0 |

| Mode of dialysis | 13 | |

| Hemodialysis | 366 (95) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 18 (5) | |

| Mean length of time in months on dialysis (range) | 50 (1–336) | 14 |

| Mean age in yr (range) | 59 (21–91) | 14 |

| Sex | 0 | |

| Male | 228 (57) | |

| Female | 169 (43) | |

| Marital status | 1 | |

| Single | 163 (41) | |

| Married | 153 (38) | |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 80 (20) | |

| Race | 0 | |

| White | 108 (27) | |

| Black | 272 (69) | |

| Othera | 17 (4) | |

| Educational attainment | 2 | |

| Less than high school | 23 (6) | |

| High school | 185 (47) | |

| Trade school/technical college | 85 (22) | |

| University/Bachelor’s degree | 51 (13) | |

| Graduate/postgraduate | 51 (13) | |

| Religious affiliation | 12 | |

| Christianity | 338 (88) | |

| Judaism | 14 (4) | |

| Islam/Hindu/Buddhism | 12 (3) | |

| Atheist/nonaffiliated | 21 (5) | |

Other race (n=17) consists of self-identified Native American, Middle Eastern, Asian, or other.

In bivariate analyses, age, sex, dialysis modality, and length of time on dialysis were not significantly associated with regret. However, regret was associated with race and questions regarding the importance of acquiring detailed knowledge about the medical condition, quality of life to determine future care, family involvement in decision making, receipt of prognostic information, advance care planning, and knowing about dialysis withdrawal options. Other significant associations of regret included the person making the decision for dialysis over conservative management (patient versus family member or a physician), previous discussions about prognosis, and presence of a living will and power of attorney (Table 1).

In the multivariable logistic regression model (Table 3), patients who reported choosing dialysis over conservative management to please doctors or family members were more likely to regret their decision (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.27 to 4.31; P<0.01). Patients who reported that their doctor had talked to them about how long they would live (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.18 to 0.98; P=0.03) and those who had completed a living will (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.95; P=0.03) were less likely to report regretting dialysis. Other significant variables in the bivariate analyses, including race and the presence of an enduring power of attorney, were not statistically significant in the multivariable analyses.

Table 3.

Final adjusted multivariable model of regret with dialysis decision

| Questions | Adjusted Odds Ratio Estimates | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you are currently receiving dialysis, why did you choose dialysis over conservative care? | |||

| Doctor’s/family’s wish versus personal wish (ref) | 2.34 | 1.27 to 4.31 | <0.001 |

| Has your doctor talked to you about how much time you have to live? | |||

| Yes versus no (ref) | 0.42 | 0.18 to 0.98 | 0.03 |

| Have you completed a living will? | |||

| Yes versus no (ref) | 0.48 | 0.25 to 0.95 | 0.03 |

| Race | |||

| Nonwhite versus white (ref) | 1.51 | 0.76 to 3.016 | 0.24 |

| How informed are you about your medical condition and how it will change over time? | |||

| Informed versus uninformed/unsure (ref) | 0.85 | 0.378 to 1.91 | 0.69 |

| How important is it for you to be informed about treatment options such as withdrawing dialysis? | |||

| Important versus unsure/unimportant (ref) | 1.19 | 0.61 to 2.30 | 0.61 |

| How important is it for your “quality of life” to affect your future care? | |||

| Important versus unsure/unimportant (ref) | 0.94 | 0.36 to 2.50 | 0.91 |

| How important is it for you to prepare and plan ahead in case of death? | |||

| Important versus unsure/unimportant (ref) | 0.57 | 0.28 to 1.15 | 0.12 |

| How important is to you for your family to be actively involved in medical decision making? | |||

| Important versus unsure/unimportant (ref) | 0.59 | 0.26 to 1.31 | 0.19 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ref, reference group.

Discussion

In this cohort of racially diverse patients in the United States who are receiving dialysis, patients who chose dialysis to please their doctors or family members were more likely to regret the decision to start dialysis. Patients who reported prognostic discussion about life expectancy with their doctor or who completed a living will were less likely to experience decisional regret. These findings suggest that nephrologists could potentially minimize patients’ decisional regret by engaging them and their families in deeper discussions about prognosis and end-of-life planning.

Our study revealed three primary findings. First, regret was more likely when patients chose dialysis over conservative management because they felt that either the doctor or their family members wanted them to choose dialysis. In these instances, patients may have merely wished to agreeably acquiesce to polite suggestions, or they may have felt that physicians or family members were covertly demanding or pressuring them to begin a treatment. In either scenario, it is unlikely that patients genuinely wanted the treatment or understood its full effect on their lives. Similar findings were reported in the National Dutch Survey, where the influence of physicians and family predicted regret (7). Patient autonomy is a critical component of medical decision making (12,13). Although a patient’s sense of autonomy in decision making is associated with good quality of life after dialysis initiation (14), few kidney failure patients report a high sense of autonomy during the decision-making process (15). Most report that “it just happened,” without them feeling like they made a proactive, considered, and self-directed choice (16). Physicians describe the process of dialysis decision making as preparing their patients to initiate dialysis rather than helping or encouraging them to make a proactive choice between dialysis and conservative management (17). If any choices are given at all, they are often secondary choices, such as choosing between different modalities of dialysis, or making a choice between arteriovenous fistula versus graft (16). In fact, many practitioners in dialysis units disagree with giving patients options to choose from (18,19). It is unclear how often requirements for informed decision making are genuinely met during dialysis decision making (20,21). Patients may resent a treatment that leaves them tired, but may not feel they have enough agency or knowledge to make a proactive decision according to their values and goals (18,22). Patients may feel caught between agreeing to a treatment that prolongs life but may entail suffering, and their fear of death and dying (23). It is psychologically challenging to withdraw from dialysis once initiated, as the alternative is death if residual kidney function is lost after dialysis initiation (16,24,25). Talking about death and dying is terrifying for many patients and few clinicians are prepared to respond to these powerful emotions (26). Managing these emotions has not historically been seen as a component of the nephrology team’s mandate, or part of their workflow (27). Therefore, communication interventions to train nephrologists in dialysis decision making are urgently needed.

Our second main finding was that regret was less likely among a small number of patients (n=40) who recalled having a discussion about life expectancy. Discussion of prognosis is a crucial component of informed decision making and plays a critical role in providing anticipatory guidance to patients and their families for end-of-life planning (28). Most patients receiving dialysis wish to discuss prognosis, but few engage in such discussions (1) and most patients overestimate their prognosis (29). Previous studies have shown that providing more information reduces regret (11). For example, parents of children with cancer reported less regret if they had received prognostic information (30). Physicians are often fearful about discussing prognosis and are apprehensive about diminishing hope in their patients (31), but those fears are misplaced. Prognostic discussions do not harm the patient–physician relationship, and in fact could strengthen it (32), as well as potentially preventing postdecisional regret.

Third, we also found that regret was less likely when patient had already completed a living will. On the basis of the bivariate analyses (Table 1), patients reporting regret do not appear to have prioritized being actively involved in decision making or planning ahead. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that they rarely engage in prognostic discussions, defer decisions to others, and are less likely to complete a living will. Patient receiving dialysis have a much higher mortality than the general population of similar age, yet the majority do not complete directives (2). Typically, they receive aggressive end-of-life care and die at a hospital, despite a wish to die comfortably (1,2). Completion of a living will provides patients with an opportunity to document their preferences and exercise their autonomy, which may contribute to the lower frequency of experiencing decisional conflict and regret in this group (11).

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Ours is one of the first United States–based studies to identify predictors of regret with dialysis decisions in a racially diverse cohort of patients. However, we excluded patients who were unable to speak English and did not collect data on prior transplant history. Moreover, despite the presence of a facilitator to explain the survey questions, some patients may have misinterpreted the questions, and only 395 out of 423 patients responded to the question about regret. Like any survey study, recall and differential misclassification biases may had influenced patients’ responses. For example, patients who report regret may be more likely to recall that others influenced their decision. This recall bias would serve to deflect “blame” away from patients themselves. We acknowledge that we used a single-item question rather than a validated scale to assess regret. Moreover, responses to the single item may reflect regret about the treatment decision, the outcome, or something else. Finally, we did not measure the severity of regret, functional status, or quality of life in these patients. Older patients with CKD have expressed maintaining functional independence as their top priority (33). However, our study did not measure functional status or quality of life; both are critical components of informed dialysis decision making, and worsening of either may potentially contribute to regret with dialysis.

Our study has several implications. First, it encourages nephrologists to engage patients in prognostic discussions, and underscores the clinical significance of living wills and the informed consent process (21,34). Prognostic discussion can strengthen the patient–physician relationship (32). Prognostic discussions could involve carefully exploring patients’ hopes, acknowledging and responding to patients’ emotions, and prognoses should be disclosed openly and honestly after seeking patient permission (35). Second, it alerts physicians that physician- or family-centered decision making without sufficient patient involvement risks higher levels of regret, whereas greater patient involvement in decision making can mitigate regret. Third, it calls for interventions to promote patient activation to enhance self-efficacy in decision making (36,37). At the policy level, patients might be less likely to experience regret if nephrology fellows and nephrologists receive training in primary palliative care skills, including goals-of-care communication, prognostic discussions, shared decision making, and documentation of end-of-life wishes (38–41). Moreover, mandating the use of bias-free decision aids and education materials during dialysis decision making may promote patient autonomy and informed decision making (42,43).

In summary, regret was more common when patients reported choosing dialysis to please doctors or family members. In contrast, regret was less common after prognostic discussions and completion of living wills. Future research should examine how interventions targeting risk factors for dialysis regret might mitigate regret by enhancing patient participation in decisions about whether and when to initiate dialysis.

Disclosures

Dr. Duberstein, Dr. Epstein, Ms. Ladwig, Dr. Monk, and Dr. Saeed have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Saeed is a recipient of University of Rochester Clinical Translational Science Institute KL2 award KL2TR001999-01, American Society of Nephrology Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar grant, and a Renal Research Institute grant.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented as a poster at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Care Meeting in Orlando, Florida, March 13–16, 2019.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeed F, Sardar MA, Davison SN, Murad H, Duberstein PR, Quill TE: Patients’ perspectives on dialysis decision-making and end-of-life care. Clin Nephrol 91: 294–300, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeelenberg M, Pieters R: A theory of regret regulation 1.0. J Consum Psychol 17: 3–18, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elwyn G, Miron-Shatz T: Deliberation before determination: The definition and evaluation of good decision making. Health Expect 13: 139–147, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svenson O: Differentiationand consolidation theory of human decision making: A frame of reference for the study of pre-and post- decision processes. Acta Psychol (Amst) 80: 143–168, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilman EA, Feely MA, Hildebrandt D, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Chong EY, Williams AW, Mueller PS: Do patients receiving hemodialysis regret starting dialysis? A survey of affected patients. Clin Nephrol 87: 117–123, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkhout-Byrne N, Gaasbeek A, Mallat MJK, Rabelink TJ, Mooijaart SP, Dekker FW, van Buren M: Regret about the decision to start dialysis: A cross-sectional Dutch national survey. Neth J Med 75: 225–234, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan EGF, Teo I, Finkelstein EA, Meng CC: Determinants of regret in elderly dialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 622–629, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreps GL: Communication and racial inequities in health care. Am Behav Sci 49: 760–774, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elias CM, Shields CG, Griggs JJ, Fiscella K, Christ SL, Colbert J, Henry SG, Hoh BG, Hunte HER, Marshall M, Mohile SG, Plumb S, Tejani MA, Venuti A, Epstein RM: The social and behavioral influences (SBI) study: Study design and rationale for studying the effects of race and activation on cancer pain management. BMC Cancer 17: 575, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becerra Pérez MM, Menear M, Brehaut JC, Légaré F: Extent and predictors of decision regret about health care decisions: A systematic review. Med Decis Making 36: 777–790, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varelius J: The value of autonomy in medical ethics. Med Health Care Philos 9: 377–388, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan RM, Deci EL: Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55: 68–78, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen MF, Chang RE, Tsai HB, Hou YH: Effects of perceived autonomy support and basic need satisfaction on quality of life in hemodialysis patients. Qual Life Res 27: 765–773, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen DL, Grootendorst DC, Rijken M, Heijmans M, Kaptein AA, Boeschoten EW, Dekker FW; PREPARE-2 Study Group : Pre-dialysis patients’ perceived autonomy, self-esteem and labor participation: Associations with illness perceptions and treatment perceptions. A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 11: 35, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufman SR, Shim JK, Russ AJ: Old age, life extension, and the character of medical choice. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 61: S175–S184, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM: Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 179: 305–313, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russ AJ, Shim JK, Kaufman SR: The value of “life at any cost”: Talk about stopping kidney dialysis. Soc Sci Med 64: 2236–2247, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, Loke R, Oskoui T, Perrone RD, Meyer KB, Weiner DE, Wong JB: Discussing conservative management with older patients with ckd: An interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 627–635, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, Arnold RM, Bridgman JC, Ward SE: Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2815–2823, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan F, Stewart C, Burgess H, Davison SN, Moss AH, Murtagh FEM, Germain M, Tranter S, Brown M: Time to improve informed consent for dialysis: An international perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1001–1009, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladin K, Lin N, Hahn E, Zhang G, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE: Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: A qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 1394–1401, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beard BH: Fear of death and fear of life. The dilemma in chronic renal failure, hemodialysis, and kidney transplantation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 21: 373–380, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt RJ, Moss AH: Dying on dialysis: The case for a dignified withdrawal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 174–180, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Loon IN, Goto NA, Boereboom FTJ, Verhaar MC, Bots ML, Hamaker ME: Quality of life after the initiation of dialysis or maximal conservative management in elderly patients: A longitudinal analysis of the Geriatric assessment in OLder patients starting Dialysis (GOLD) study. BMC Nephrol 20: 108, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodenbach RA, Rodenbach KE, Tejani MA, Epstein RM: Relationships between personal attitudes about death and communication with terminally ill patients: How oncology clinicians grapple with mortality. Patient Educ Couns 99: 356–363, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry E, Swartz R, Smith-Wheelock L, Westbrook J, Buck C: Why is it difficult for staff to discuss advance directives with chronic dialysis patients? J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2160–2168, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook SA, Damato B, Marshall E, Salmon P: Psychological aspects of cytogenetic testing of uveal melanoma: Preliminary findings and directions for future research. Eye (Lond) 23: 581–585, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Hare AM, Kurella Tamura M, Lavallee DC, Vig EK, Taylor JS, Hall YN, Katz R, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA: Assessment of self-reported prognostic expectations of people undergoing dialysis: United States renal data system study of treatment preferences (USTATE) [published online ahead of print Jul 8, 2019]. JAMA Intern Med 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack JW, Cronin AM, Kang TI: Decisional regret among parents of children with cancer. J Clin Oncol 34: 4023–4029, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mack JW, Smith TJ: Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol 30: 2715–2717, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenton JJ, Duberstein PR, Kravitz RL, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, Fiscella K, Mohile S, Epstein RM: Impact of prognostic discussions on the patient-physician relationship: Prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 36: 225–230, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramer SJ, McCall NN, Robinson-Cohen C, Siew ED, Salat H, Bian A, Stewart TG, El-Sourady MH, Karlekar M, Lipworth L, Ikizler TA, Abdel-Kader K: Health outcome priorities of older adults with advanced ckd and concordance with their nephrology providers’ perceptions. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2870–2878, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu JH: Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [1]: CD001431, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, Lobb EA, Pendlebury SC, Leighl N, MacLeod C, Tattersall MH: Communicating with realism and hope: Incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol 23: 3652, 2005]. J Clin Oncol 23: 1278–1288, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shively MJ, Gardetto NJ, Kodiath MF, Kelly A, Smith TL, Stepnowsky C, Maynard C, Larson CB: Effect of patient activation on self-management in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 28: 20–34, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hibbard JH, Greene J: What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 32: 207–214, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quill TE, Abernethy AP: Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 368: 1173–1175, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurella Tamura M, O’Hare AM, Lin E, Holdsworth LM, Malcolm E, Moss AH: Palliative care disincentives in CKD: Changing policy to improve CKD care. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 866–873, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah HH, Monga D, Caperna A, Jhaveri KD: Palliative care experience of US adult nephrology fellows: A national survey. Ren Fail 36: 39–45, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rusiecki J, Schell J, Rothenberger S, Merriam S, McNeil M, Spagnoletti C: An innovative shared decision-making curriculum for internal medicine residents: Findings from the university of pittsburgh medical center. Acad Med 93: 937–942, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krones T, Keller H, Sönnichsen A, Sadowski EM, Baum E, Wegscheider K, Rochon J, Donner-Banzhoff N: Absolute cardiovascular disease risk and shared decision making in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 6: 218–227, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis JL, Davison SN: Hard choices, better outcomes: A review of shared decision-making and patient decision aids around dialysis initiation and conservative kidney management. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 26: 205–213, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]