Abstract

Arabinosyltransferase B (EmbB) belongs to a family of membrane-bound glycosyltransferases that build the lipidated polysaccharides of the mycobacterial cell envelope, and are targets of anti-tuberculosis drug ethambutol. We present the 3.3 Å resolution single-particle cryo-electron microscopy structure of Mycobacterium smegmatis EmbB, providing insights on substrate binding and reaction mechanism. Mutations that confer ethambutol resistance map mostly around the putative active site, suggesting this to be the location of drug binding.

Subject terms: Transferases, Tuberculosis, Cryoelectron microscopy

The cryo-EM structure of Mycobacterium smegmatis arabinosyltransferase B EmbB involved in mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis provides insights into the substrate binding and reaction mechanism. Mapping of the ethambutol resistance associated mutations onto the structure suggests the location of the drug binding site.

Introduction

The cell envelope is crucial for growth and virulence of pathogenic mycobacteria like M. tuberculosis1 and is a major contributor to resistance against common antibiotics2. Its main component is the mycolyl-arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan complex, which consists of peptidoglycan, a branched heteropolysaccharide arabinogalactan (AG) and long chain mycolic acids (Fig. 1a). Another major component is the lipidated heteropolysaccharide lipoarabinomannan (LAM)3. Of the enzymes involved in mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis, arabinofuranosyltransferases are responsible for the addition of D-arabinofuranose sugar moieties to AG and LAM2. These transmembrane (TM) enzymes utilize decaprenylphosphoryl-D-arabinofuranose (DPA) to transfer an arabinofuranose unit to the growing lipidated polysaccharides of the cell envelope4.

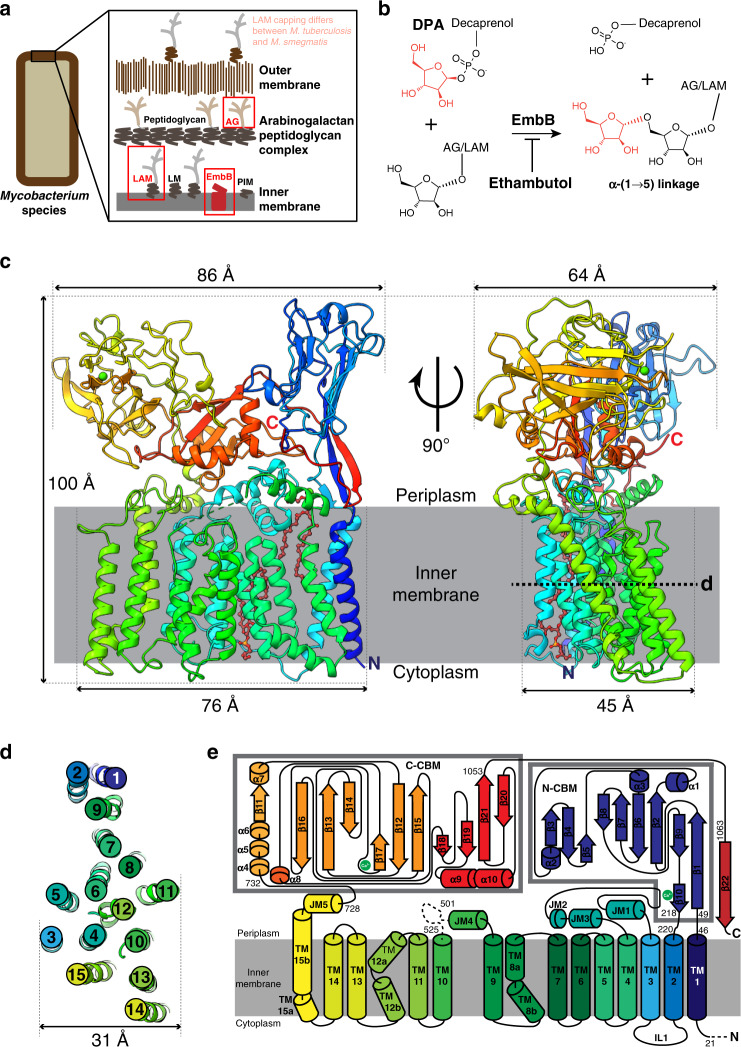

Fig. 1. Cryo-EM structure of EmbB.

a Model of the cell envelope of mycobacterial cell envelope based on Dulberger et al.75. Red boxes highlight arabinogalactan (AG) and lipoarabinomannan (LAM) components, synthesized by EmbA/EmbB (red) and EmbC, respectively. LAM for M. tuberculosis is capped by α-mannose glycans while in M. smegmatis it is capped by phosphoinositol instead76. b Reaction catalyzed by EmbB, which is inhibited by ethambutol. c Single-particle cryo-EM structure of EmbB, rendered in cartoon form and colored in rainbow from N terminus (blue) to C terminus (red). A Ca2+ ion is shown as a green sphere. The bound lipids are represented as ball-and-sticks, colored in brown. Two orthogonal views that are perpendicular to the plane of the membrane are shown. Membrane boundaries were derived from the interface between the nanodisc lipids and solvent. d Arrangement of the TM helices of EmbB, viewed as a slice in the plane of the membrane, as indicated in (b) and magnified. e Two-dimensional topological diagram of EmbB. The two CBMs are enclosed in separate gray boxes. The topology diagram is rainbow colored from N terminus (blue) to C terminus (red). Unbuilt parts of the model, due to poor map density, are indicated by dotted lines. Bound Ca2+ atoms are shown as green circles.

Arabinosyltransferase B (EmbB), a 117 kDa integral membrane enzyme involved in the α-(1→5)-linked extension of the AG arabinan chain (Fig. 1b), is one of the best characterized members of the aforementioned family5,6. Its gene belongs to an operon coding for two other homologous arabinosyltransferases EmbA (40% identity between M. smegmatis EmbB and EmbA, 42% identity in M. tuberculosis, acts also on AG) and EmbC (46% identity between M. smegmatis EmbB and EmbC, 44% identical in M. tuberculosis, acts on LAM) (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The operon was named due to the sensitivity of these gene products to ethambutol, a first-line antibiotic against tuberculosis7 and nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease8. EmbB and EmbC have mutations known to lead to ethambutol resistance9, while a clear effect of the drug on EmbA activity has not been established10. The dearth of atomic models of these proteins—only a high resolution structure of the C-terminal soluble domain of EmbC is available11—has thus far hindered our understanding of the catalytic action and drug resistance mechanisms of these proteins, although this situation has been recently remedied to a certain extent by eludication of structures of the EmbA–EmbB and EmbC–EmbC dimer complexes12. Here, we report the structure of M. smegmatis EmbB to 3.3-Å resolution, providing insights on substrate binding and reaction mechanism. Mutations that confer ethambutol resistance map mostly around the putative active site, suggesting this to be the location of drug binding.

Results and discussion

Cryo-EM structure of M. smegmatis EmbB

To better understand the function of EmbB at a molecular level, we adopted a structural genomics approach that identified the M. smegmatis ortholog (68% identical in M. tuberculosis), out of 14 screened, as a suitable candidate for structural studies based on expression levels in E. coli and stability in detergents compatible with structure determination13. Using single-particle cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), we determined the structure of EmbB from M. smegmatis expressed in E. coli and reconstituted in lipid-filled nanodiscs to 3.3 Å resolution (Supplementary Figs. 3–5 and 6a, and Table 1). Here, EmbB appears as a monomer, consisting of 15 TM helices and two distinct periplasmic carbohydrate binding modules (CBMs) (Fig. 1c–e). The first two TM helices are not found in other glycosyltransferase structures solved to date, and seem to serve to anchor the N-terminal CBM (N-CBM) to the membrane. The next 11 TM helices adopt a typical GT-C glycosyltransferase fold14, structurally similar to enzymes from various glycosyltransferase families: mycobacterial AftD from GT5315, archaeal ArnT from GT8316, yeast Pmt1-Pmt2 from GT3917, and bacterial PglB from GT6618 (Supplementary Fig. 7a–f). The last two TM helices are shared only with ArnT. Thereafter, the polypeptide chain exits the membrane in the periplasm to form the second C-terminal CBM (C-CBM). The C-CBM then loops back around to complete a β-sheet with the N-CBM, likely to secure the N-terminal domain in place.

Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection and modeling statistics EmbB.

| Session 1 | Session 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Microscope | FEI Titan Krios (same microscope) | |

| EM data collection/processing | ||

| Magnification | 120,000 | 37,000 |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 | |

| Camera | Falcon III | Gatan K2 Summit |

| Mode | Counting | Counting |

| Set defocus range (μm) | 0.5–2.5 | 0.3–2.9 |

| Defocus mean ± std (μm) | 1.8 ± 0.29 | 1.9 ± 0.27 |

| Exposure time (s) | 86.4 | 8 |

| Number of frames | 80 | 80 |

| Dose rate (e−/pixel/s) | 0.4 | 4.3 |

| Total dose (e−/Å2) | 78.02 | 77.53 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 0.665 | 0.667 |

| Number of micrographs | 2158 | 7833 |

| Number of particles (after initial cleanup) | 162,271 | 700,201 |

| Number of particles (in final map) | 57,970 | |

| Symmetry | C1 | |

| Resolution (global) (Å) | 3.3 | |

| Local resolution range | 2.8–16.0 | |

| Directional resolution range | 3.0–3.4 | |

| Sphericity of 3DFSC | 0.99 | |

| SCF valuea | 0.98 | |

| Map sharpening b-factor (Å2) | −72.5 | |

| Model statistics | ||

| Initial model used (PDB code) | 3PTY | |

| Map-to-model resolution (Å) | 3.4 | |

| Model composition | ||

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 15,844 | |

| Residue range | 21–500, 526–1082 | |

| Ligands | 4 | |

| Map CC | 0.743 | |

| RMSD [bonds] (Å) | 0.0065 | |

| RMSD [angles] (Å) | 1.21 | |

| All-atom clashscore | 2.67 | |

| B factors (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 44.96 | |

| Ligands | 44.63 | |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored (%) | 94.87 | |

| Allowed (%) | 5.05 | |

| Outliers (%) | 0.08 | |

| Rotamer outliers | 0.00 | |

| C-β deviations | 0 | |

| MolProbity score | 1.41 | |

| EM-Ringer score | 3.14 | |

aThe SCF value is calculated as described66, but currently assumes that all orientations have been properly assigned and does not take into account false positive assignment.

Mapping of the putative active site

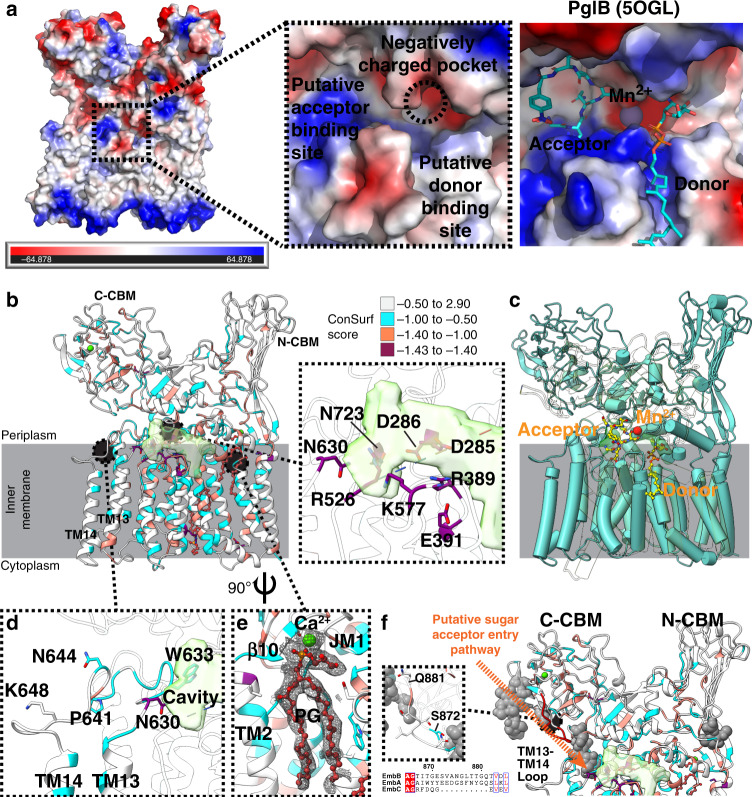

EmbB has a single large cavity (volume of ~1120 Å3) at the membrane–periplasm interface that encompasses juxtamembrane (JM) helix 4 and a disordered stretch of around 20 residues between JM4 and TM10 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Conservation analyses reveal that this cavity contains highly conserved charged residues (D285, D286, R389, E391), where the residues corresponding to D285 and D286 are required for catalytic activity of corynebacterial EmbB (D297 and D298)19 and mycobacterial EmbC (D293 and D294)20 (Fig. 2a). The putative active site has a number of negatively charged amino acids—D285, D286, and E313—which would help stabilize the carbon with a partial positive charge in the anticipated exploded SN2-like transition state21. Structural alignments with the other GT-C structures all show superimposition of their active site with this cavity. For instance, in PglB, both the donor, the acceptor and a catalytic Mn2+ localize here (Fig. 2a, c). Based on this structural comparison, the lipidic donor (DPA) is likely to bind in the pocket formed by TM helices 7–9, on the right side of the cavity, with the soluble acceptor substrate binding to the left. As this structure was determined in the absence of any bound ligands, we expect the disordered residues between JM4 and TM10 to become ordered upon substrate binding, akin to what was shown for the PglB EL518 and ArnT PL4 loops16 (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f).

Fig. 2. Structural features of EmbB.

a Electrostatic representation of EmbB, with a zoom-in around the putative active site, labeled according to where the substrates are likely to bind, where red is more negatively charged and blue more positively charged. A comparison with the PglB active site with bound substrates is also shown, after PglB was aligned against EmbB. b Structure of EmbB, rendered in cartoon and colored based on ConSurf69 score for sequence conservation. The more negative the score, the more conserved the residue. The putative active site cavity, generated by the Voss Volume Voxelator server68 is colored in semi-transparent green. The insert shows the putative active site cavity with the strictly conserved residues labeled. c EmbB (pale blue) is superimposed on PglB (semi-transparent yellow), with the ligands and Mn2+ ion of PglB shown in yellow as sticks and a ball, respectively. d Residues that are known to maintain catalytic activity while altering substrate specificity on a loop between TM13 and TM14 are labeled and side chains are shown. e A tightly bound phosphatidylglycerol (PG shown as ball-and-stick) and calcium ion (shown as a ball) in a pocket between TM2, JM1, and β10 is shown. The density map of the lipid and the ion is displayed as mesh. f Glycan ligands for the top ten Dali server hits for both N-CBM and C-CBM were mapped onto the structure as a gray ball representation. 2WJS [10.2210/pdb2WJS/pdb] (PDB ID) was used for N-CBM, while 3PTY [10.2210/pdb3PTY/pdb] and 4GWM [10.2210/pdb4GWM/pdb] were used for the C-CBM. The missing loop in EmbC is colored in red, and the insert is a zoomed-in view. Sequence alignment of the region around the loop is appended below the insert. The putative sugar acceptor entry pathway is shown as an orange dotted line.

While active site mutants in EmbB result in suppressed bacterial growth19, a series of mutations (N630, W633, P641, N644, K648) have been shown to retain enzymatic activity yet reduce incorporation of arabinose, resulting in the formation of a truncated AG19. Similar findings have been reported for LAM in EmbC20,22. All these residues map to the loop between TM helices 13 and 14, situated at the entrance of the cavity for the putative sugar acceptor (Fig. 2d), suggesting a role for it in regulating the oligosaccharides that can act as acceptors for EmbB19,20.

Presence of tightly bound lipids in EmbB

We observe two bound lipids in our structure, in a pocket formed by TM helices 2, 5, 6, 7, and 9 on opposite leaflets (Fig. 1c). The lipid on the outer leaflet appears to have a cation bound to its head group, mediating extensive interactions with the backbone and side chains of residues from TM2, JM1, and β10 (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 7g). To identify these lipids, we performed native mass spectrometry (MS) of EmbB, which showed that EmbB appeared as a dimer when solubilized in detergent C12E8 with a series of bound molecules with masses around 300–350 Da (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In addition, there were two peaks that showed larger abundances, and we hypothesize that these corresponded to two or three bound lipid molecules with masses of ~750 Da (Supplementary Fig. 8a). To remove bound adducts, we also performed denatured liquid chromatography–MS analysis. Under denaturing conditions, EmbB retained a tightly bound calcium ion (Supplementary Fig. 8b). An additional peak was observed with 749 ± 21 Da mass, which also partially retained a calcium ion. This mass is consistent with a bound phosphatidylglycerol (PG), which is also present in mycobacterial inner membranes (average molecular weight 761.073 Da)23,24. These lipids (or equivalent ones endogenously) may be important in stabilizing the protein structure (Supplementary Fig. 7g).

EmbB has two carbohydrate binding modules

In the periplasmic region, the two CBMs exhibit β-sandwich folds. Using the top ten hits from the Dali server25, structurally similar CBMs were aligned with the two CBMs of EmbB. This allowed us to interrogate the possible glycan-binding locations; potential substrates that were sterically hindered in the EmbB structure were discarded. As expected, the EmbB C-CBM structure is highly homologous to the corresponding CBM in EmbC (PDB ID: 3PTY [10.2210/pdb3PTY/pdb])11, with an RMSD of 1.2 Å. N-CBM’s structural homologs bind to at most one monosaccharide unit, whereas structural homologs of the C-CBM reveal binding to more complex glycans, corroborating what was previously observed for the EmbC C-CBM11. The co-crystallized Ara-(1 → 5)-Ara-O-C8 ligand for the EmbC C-CBM maps to the loop of EmbB between TM helices 13 and 14, which we earlier proposed to control access of the acceptor to the active site (Fig. 2f). This suggests a pathway for the binding of the acceptor in the active site exclusively via the C-CBM (Fig. 2f). By screening purified EmbB against a synthetic array of mycobacterial glycan fragments26, we found that the protein preferentially binds highly-branched arabinose-containing oligosaccharides (Supplementary Fig. 9), supporting the hypothesis that the C-CBM binds to multiple monosaccharide residues.

A comparison of EmbA, EmbB, and EmbC sequences revealed that a loop region spanning from S872 to Q881 is missing in EmbC (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 2). In EmbB, this loop is located directly above the TM13-14 loop and is part of the C-CBM; it is in the path we propose the acceptor might take to bind. This could explain the different substrate specificities reported of the Emb family members: EmbA and EmbB act specifically on AG, while LAM is a substrate of EmbC, even though all enzymes catalyze the same reaction: addition of an arabinose residue α-(1→5) to an existing arabinan chain1.

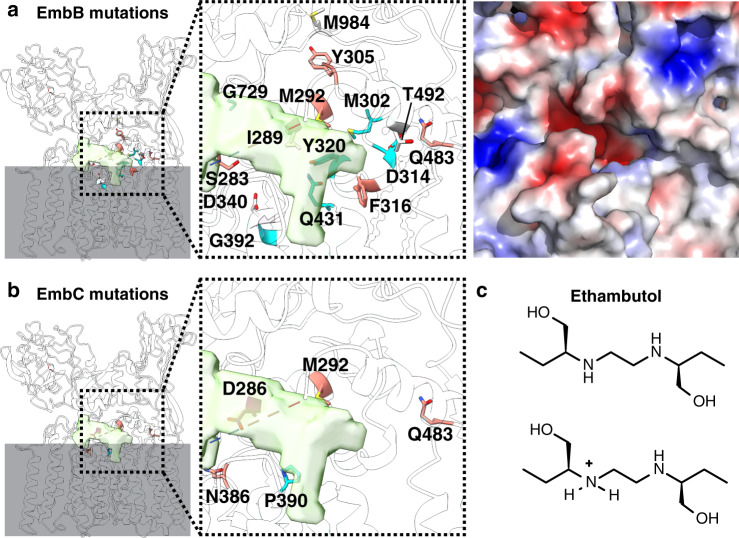

Ethambutol resistance mutations map to putative active site

The structure of EmbB presents the unique opportunity to spatially map out data resulting from decades of known ethambutol resistance mutations in both EmbB and EmbC9,27–30. Focusing only on residues conserved between M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis (Supplementary Table 1), we found that mutations causing resistance all cluster around the putative active site (Fig. 3a). Notably, these mutations are closer to the putative DPA binding site, suggesting that ethambutol might interfere with recruitment of the arabinose donor, thereby inhibiting enzyme function. Most mutated residues are not highly conserved, which both follows evolutionary logic in terms of maintaining structural integrity and function, and also provides a template to predict residues that might be susceptible to drug-induced mutations in the future. Based on the reported pKa’s for ethambutol (pKa1 = 6.35, pKa2 = 9.3)31, the drug is expected to be positively charged at physiological pH, suggesting that ionic interactions are involved in drug binding (Fig. 3c). Indeed, many of the mutations are conversions of negatively charged residues into uncharged ones (D314G/Y, D340A), or of uncharged residues into positively charged ones (Q431R, Q483K, T492R, M984R) (Fig. 3a). The only two mutations decreasing the protein overall net charge (G392D, G729D) are from residues located at the periphery of the cavity. Moreover, the homology between EmbB and EmbC enabled us to map the EmbC mutations that contributed to drug resistance onto the EmbB structure (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 2). Again, these mutations cluster around the putative DPA binding site. Surprisingly though, the highly conserved D286 residue is also involved in drug resistance in EmbC, which could be explained by the fact that D286G mutation reduces but does not abolish the catalytic activity of EmbC29.

Fig. 3. Ethambutol resistance mutations of EmbB and EmbC.

Mutations known to confer resistance to ethambutol in EmbB (a) and EmbC (b) are mapped on the overall structure and as a zoom-in, with their side chains displayed and colored based on the ConSurf score as in Fig. 2. The other regions of the EmbB model are rendered semi-transparent. The electrostatic potential of the zoom-in region of EmbB is shown on the right. c Chemical structure of (S, S)-ethambutol, showing both its neutral and one of two single positively charged forms.

Comparison with heterodimeric Emb structures

Recently, the structures of heterodimeric M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis EmbA, EmbB, and EmbC were determined12. M. smegmatis EmbB was solved as a dimer with EmbA, bound to either ethambutol or di-arabinofuranose (Supplementary Fig. 10). Compared with our monomeric, apo-structure, the disordered residues between JM4 and TM10 indeed become ordered; the rest of the structure, however, is very similar (Supplementary Fig. 10c). Whether the ordering of these residues is caused by the addition of substrates or hetero-dimerization is yet to be determined. Notably, the dimeric M. smegmatis EmbA–EmbB was overexpressed endogenously and surprisingly had meromycolate extension ACP (AcpM) bound, the same AcpM that is also associated to mycobacterial arabinofuranosyltransferase AftD15. Our monomeric EmbB structure does not have the AcpM bound likely because it was expressed heterologously in E. coli. AcpM in the EmbA–EmbB dimer structure extends its 4′-phosphopantetheine into the same pocket as that of inner leaflet PG present in our monomeric EmbB structure (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 10b). The lack of AcpM did not cause any significant conformational changes in the structure of EmbB around the AcpM binding site, suggesting that AcpM might not have a critical functional role, unlike what seems to occur in AftD (Supplementary Fig. 10c).

In conclusion, we report the full-length monomeric structure of a mycobacterial arabinosyltransferase from the Emb family. The structure was obtained by cryo-EM in close to the native environment by its incorporation into a lipid-filled nanodisc, and the data show that EmbB has a conserved GT-C fold. Analysis of the structure allowed us to map the putative active site as well as substrate binding sites. We localized mutations that maintain catalytic activity while altering substrate specificity to a loop between TM13 and TM14, juxtaposed to the putative active site, which we propose controls access of the acceptor to the active site. A tightly bound phosphatidylglycerol lipid and calcium cation that likely serve a structural purpose were evident in the density map, and their presence and identity were confirmed using native and denaturing mass spectrometry. Mapping of known ethambutol mutations on the structure suggests that this drug binds in close proximity of the putative active site, providing a framework to better understand if not predict resistance-causing loci. Finally, our work provides a template for future structure-based drug design efforts aimed at enhancing the efficacy of this front-line drug that is effective against tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis32, M. bovis33, M. microti34) and NTM disease32 (M. avium, M. kansaii35). This is of particular importance in the face of increasingly frequent infections with drug resistant strains of M. tuberculosis7 and other disease-causing mycobacteria32,35–37. Note that our solved structure of EmbB is from M. smegmatis, a model species for the entire mycobacteria family37 that is non-pathogenic. Hence, not all observations might be directly transferrable to the aforementioned pathogenic mycobacterial species, but should instead serve a guide for future studies of this family of enzymes.

Methods

Statistics

For calculations of Fourier shell correlations (FSC), the FSC cut-off criterion of 0.14338 was used. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized. The researchers were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Sequence alignment

Protein sequences of EmbA, EmbB, and EmbC from M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis were obtained from the Mycobrowser39, with the following KEGG identifiers: EmbA Mtb—Rv3794, EmbB Mtb—Rv3795, EmbC Mtb—Rv3793, EmbA Msm—MSMEG_6388, EmbB Msm—MSMEG_6389, and EmbC Msm—MSMEG_6387. The sequences were then aligned using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/)40 and displayed using ESPript (http://espript.ibcp.fr)41.

Genomic expansion and small-scale screening

EmbB genes were identified from a collection of 14 Mycobacterium genomes using a bioinformatics approach13. Ligation independent cloning (LIC) was used to clone these targets from the genomes into five LIC-adapted expression vectors (pNYCOMPS-Nterm, pNYCOMPS-Cterm, pNYCOMPS-N23, pNYCOMPS-C23, and pMCSG7-10x) that contained a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site (ENLYFQSYV) and decahistidine affinity tag. Small and medium scale expression was performed in a high throughput manner as described in detail in a previous protocol by Bruni and Kloss42. A number of orthologs could be cloned and expressed well, but M. smegmatis embB was chosen over the others because it represents a model organism used to the study pathogenic M. tuberculosis. M. smegmatis embB was ultimately cloned using LIC into a pMCSG21 expression vector43 that contained a TEV protease cleavage site and Strep-tag on the 3′ end of the insert. This expression construct was used for all subsequent experiments.

EmbB expression, purification, and nanodisc reconstitution

M. smegmatis embB in the pMCSG21 plasmid was transformed into BL21 (DE3) pLysS E. coli competent cells and plated onto Luria broth (LB) agar (Fisher) plates supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin (Sigma) and 100 μg mL−1 spectinomycin (Sigma), and grown overnight at 37 °C. In the next day, a colony was picked and used to inoculate a starter culture containing 150 mL of 2xYT medium (Fisher) supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin and 100 μg mL−1 spectinomycin. The starter culture was grown overnight at 37 °C in an incubator (New Brunswick Scientific) shaking at 240 r.p.m. The following day, six 2-L baffled flasks each with 800 mL of 2xYT medium (Fisher) supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin and 100 μg mL−1 spectinomycin were inoculated with 10 mL of starter culture. The cultures were then grown at 37 °C shaking at 240 r.p.m. until cells reached an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of ~1.0 (~3 h). Temperature was then reduced to 22 °C and protein expression was induced by addition of 0.2 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fisher). The culture was then incubated overnight shaking at 240 r.p.m. The next day, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 × g utilizing a H6000A/HBB6 rotor (Sorvall) for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in chilled 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged again at 4000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was again discarded and the pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 10 μg mL−1 DNase I (Roche), 8 μg mL−1 RNase A (Roche), 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), 1 mM PMSF, 1 tablet in 1.5 L buffer EDTA-free cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). For a 4.8 L of culture, the yield corresponded to ~10–20 g of wet cell pellet mass, which was resuspended with ~250 mL of lysis buffer. Cells were lysed by passing the suspension through a chilled Emulsiflex C3 homogenizer (Avestin) three times. The crude membrane fraction was isolated by ultracentrifugation at 37,000 × g in a Type 45 Ti Rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in the lysis buffer up to a volume of 240 mL and homogenized using a hand-held glass homogenizer (Konte). The membrane fraction was then stored at −80 °C until later use to purify protein.

The thawed membrane fraction was solubilized by adding n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) to a final concentration of 1% (w/v) detergent for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation. Insoluble material was removed by ultracentrifugation at 40,000 × g in Type 45 Ti Rotor at 4 °C for 30 min. 1.5 mg of avidin (IBA Lifesciences) was added to the supernatant to block any endogeneous biotin, and the mixture was left on ice for 5 min. Thereafter, the supernatant was added to six Falcon tubes containing pre-equilibrated Strep-Tactin® Superflow resin (IBA Lifesciences) and incubated with gentle rotation at 4 °C for 2 h. The resin was washed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 0.1% DDM and eluted with elution buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM D-biotin (Alfa Aesar), 0.05% DDM. The eluted protein was exchanged into a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 0.05% DDM using a PD-10 desalting column (GE), and concentrated down using a 100-kDa concentrator (Pierce) to ~1 mg mL−1.

The protein was then incorporated into lipid nanodisc44 with a molar ratio 1:300:6 between EmbB:1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (POPG) (Avanti):membrane scaffold protein 1E3D1 (MSP1E3D1) and incubated for 2 h with gentle agitation at 4 °C. The POPG was prepared by adding the solid extract to deionized water to a final concentration of 20 mM. The mix was placed on ice and then gently sonicated with a tip sonicator (Fisher Scientific) to dissolve the lipids. The lowest power setting was used and sonication was stopped when the mixture turned from cloudy to semi-transparent, after approximately five cycles. No detergent was added to the lipid extract. Reconstitution was initiated by removing detergent with the addition of 150 mg Bio-beads (Bio-Rad) per mL of protein solution for overnight with constant rotation at 4 °C. Bio-beads were removed by passing the protein solution through an Ultrafree centrifugal filter unit (Fisher) at 4000 × g in a Centrifuge 5424R (Eppendorf) at 4 °C for 1 min and the nanodisc reconstitution mixture was re-bound to fresh Strep-Tactin® Superflow resin for 2 h at 4 °C in order to remove empty nanodisc. The resin was washed with 10 column volumes of wash buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, followed by three column volumes of elution buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 50 mM D-biotin.

The eluent was concentrated using a 100-kDa concentrator to under 500 μL and loaded onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in gel filtration buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 200 mM NaCl). Throughout the entire process of purification, 15 μL of samples were taken and added to 5 μL of 6X reducing Laemmli SDS sample buffer (Bioland Scientific). The samples were then loaded on a 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast protein gel (Bio-Rad) for protein gel electrophoresis in a Tris/Glycine/SDS buffer. The gel was developed using InstantBlue (Sigma) protein stain.

Negative stain electron microscopy

Purified EmbB in nanodiscs was diluted to 0.005 mg/ml and applied onto copper grids (Ted Pella). These grids were overlaid by a thin (∼1.5 nm) layer of continuous carbon that had been plasma-cleaned (Gatan Solarus) for 30 s using a mixture of H2 and O2. Thereafter, filter paper (Whatman 4) was used to remove the protein solution. Three microliters of 2% uranyl formate was then added and immediately removed by absorbing with filter paper—this was repeated seven times. The grid was imaged on a Tecnai TF20 microscope (FEI) equipped with a Tietz F416 CCD camera (Tietz) at 1.10 Å per pixel, respectively, using the Leginon software package45. Seventy seven images were collected and processed using the Appion software package46 to obtain 2D classes with Relion 2.147,48. The micrographs showed good particle dispersion and homogeneity.

Single-particle Cryo-EM sample vitrification

Purified EmbB was concentrated using a 100-kDa concentrator (Pierce) between 5 and 20 μL of sample at ~8 mg mL−1. 1 mM of ethambutol (Sigma) was added before vitrification. 2.5 μL of sample was added to a plasma-cleaned (Gatan Solarus) 0.6/1.0 µm holey gold grid (Quantifoil UltrAuFoil) and blotted using filter paper on one side for 2 s using the Leica GP plunger system before plunging immediately into liquid ethane for vitrification. The plunger was operating at 5 °C with >80% humidity to minimize evaporation and sample degradation.

Data acquisition

Images were recorded in two sessions. The first session was on a Titan Krios electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a Falcon III direct detector operating at 0.665 Å per pixel in electron counting mode using the Leginon software package45. Pixel size was calibrated after obtaining a preliminary map by docking with a crystal structure of a homolog of the soluble part of EmbB (PDB ID: 3PTY [10.2210/pdb3PTY/pdb])11. Data collection was performed using a dose of ~78.02 e− Å−2 across 80 frames (1080 ms per frame) at a dose rate of ~0.40 e– pix−1 s−1, using a set defocus range of −0.5 to −2.5 μm. In all, 100-μm objective aperture was used. A total of 2158 micrographs were recorded over 3 days using an image beam shift data collection strategy49.

The second session was on a Titan Krios electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a K2 summit direct detector operating at 0.667 Å per pixel in counting mode using the Leginon software package45. Pixel size was calibrated in-house using a proteasome test sample. Data collection was performed using a dose of ~77.53 e− Å−2 across 80 frames (100 ms per frame) at a dose rate of ~4.3 e– pix−1 s−1, using a set defocus range of −0.3 to −2.9 μm. In all, 100-μm objective aperture was used. A total of 7833 micrographs were recorded over three days using an image beam shift data collection strategy49.

During data collection, movie frames were aligned using MotionCor250 with 5 by 5 patches and B-factor of 100 through the Appion software package46. Micrograph CTF estimation was performed using both CTFFind451 and GCTF52, and best estimate based on confidence was selected within the Appion software package. The aligned frames and corresponding CTF allowed for monitoring of the collection process in real time.

Data processing

Data from the two sessions were processed separately and combined toward the end of the processing pipeline. For the first Falcon III dataset, movie frames were aligned using MotionCor250 with 5 by 5 patches and B-factor of 500 for global alignment and 100 for local alignment through the Relion package47,48. Micrograph CTF estimates were imported from Appion. Ice thickness measurements were used to filter out micrographs containing ice thicker than 100 nm53. Template-free particle picking with Gautomatch (Kai Zhang, unpublished, https://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/kzhang/Gautomatch/) using an extremely lenient threshold (to avoid missing any particles) was used to pick particles (extracted 384 box size binned to 256) that were transferred into Relion 2.1 for 2D classification. 2D class averages that were ice or showed no features were discarded, resulting in 162,271 particles. The particle stack was then brought into CryoSPARC54 where repeated rounds of two class ab initio and 2D classification were used to clean up the particle stack down to 19,755 particles. The repeated rounds of two class ab initio classification was necessary because of the slight preferred orientation of EmbB—this allowed for the trimming of the dominant views while retaining the less populated ones to give a more directional isotropic reconstruction. GCTF was then used to estimate per-particle CTF and the resulting particle stack was refined to 4 Å in resolution using CryoSPARC non-uniform refinement55. Particle polishing was then performed on the particle stack through Relion. The polished particle stack was then put through cisTEM56 for CTF refinement to obtain better defocus values. The particles with the refined defocus values were then put through another round of CryoSPARC ab initio to further clean up the particle stack and a final non-uniform refinement produced a 3.4 Å map.

For the second K2 summit dataset, movie frames were aligned using MotionCor2 with 5 by 5 patches and B-factor of 500 for global alignment and 100 for local alignment through the Relion package. Micrograph CTF estimates were imported from Appion. Ice thickness measurements were used to filter out micrographs containing ice thicker than 100 nm. Template-free particle picking with Gautomatch using an extremely lenient threshold (to avoid missing any particles) was used to pick particles (extracted 384 box size binned to 256) that were transferred into Relion 2.1 for 2D classification. 2D class averages that were ice or showed no features were discarded, resulting in 700,201 particles. The particle stack was then brought into CryoSPARC where repeated rounds of two class ab initio and 2D classification were used to clean up the particle stack down to 39,702 particles, for the same rationale as stated for the first dataset. GCTF was then used to estimate per-particle CTF52. Particle polishing was not done for this dataset. The particle stack was then put through cisTEM56 for CTF refinement to obtain better defocus values. The particles with the refined defocus values were then put through another round of CryoSPARC ab initio to further clean up the particle stack and a final non-uniform refinement produced a 3.3 Å map.

At this point, both datasets were combined, which was possible because of almost identical pixel size between them (0.9975 Å versus 1.0005 Å). A common pixel size value of 1.00 Å was used for this combined dataset of 57,970 particles. Non-uniform refinement in CryoSPARC produced a 3.3 Å final map, which was locally sharpened with a b-factor of −72.5 Å2. Although resolution did not improve after combining, the map features look slightly better in the combined map versus the individual maps from either camera, hence the final map combined both stacks was used.

All conversions between Relion, CryoSPARC, and cisTEM were performed using Daniel Asarnow’s pyem script (10.5281/zenodo.3576630).

One millimolar of the drug ethambutol was added before vitrification for this dataset—however, when data was collected without the drug, a 3.7 Å reconstruction was obtained and when compared to the 3.4 Å reconstruction where the drug was added, no differences were observed. Hence the higher resolution map was used for analysis and model building.

Model building and refinement

Density modification was applied to the map using phenix.resolve_cryo_em57. The crystallized structure of the C-terminal soluble domain of EmbC11 was docked into EmbB with Chimera58 and used as a starting point for model building. Coot59 was used for manual model building. After the model was built, it was refined against the cryo-EM map utilizing real space refinement in the Phenix program60,61. Restraints for the lipids were generated using phenix.eLBOW and for the metal ions using phenix.ready_set. Thereafter, model adjustment and refinement were performed iteratively in Coot and Phenix, with the statistics being examined using Molprobity62 until no further improvements were observed. Residues 1–20, 501–525, and the C-terminal purification tag had poor density and were not built in the model. The final map and model were then validated using (1) EMRinger63 to compare a map with a model, (2) CryoSPARC’s blocres implementation64 to calculate map local resolution, (3) 3DFSC program suite65 to calculate degree of directional resolution anisotropy through the 3DFSC, and (4) SCF program66 to calculate the sampling compensation factor (SCF), which quantifies how inhomogeneity in Euler angle distributions contributes to attenuation of the FSC. Map-to-model FSCs were also calculated by first converting the model to a map using Chimera molmap function at Nyquist resolution (2 Å). A mask was made from this map using Relion (after low-pass filtering to 8 Å, extending by 1 pixel and applying a cosine-edge of 3 pixels), and was then applied to the density map. Map-to-model FSC was calculated using EMAN67 proc3d between these maps.

Model analysis

A cavity search using the Solvent Extractor from Voss Volume Voxelator server68 was performed using an outer probe radius of 5 Å and inner probe radius of 2 Å. In order to search for other PDB structures with similar fold, a Dali server25 search was performed—first globally and then against the different domains of the model. The Dali server was used to generate the structural conservation figures. Coot SSM superpose was used to align structures of other glycosyltransferases against EmbB. ConSurf69 was used for generating sequence conservation data for the structure.

Mass spectrometry

EmbB was buffer exchanged into 0.2 M ammonium acetate at pH 6.8 (Sigma-Aldrich) with either 0.01% C12E8 (Anatrace) or 0.02% DDM (Anatrace) detergent using gel filtration. Native mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of EmbB in C12E8 detergent was performed using a Q-Exactive HF Orbitrap with Ultra High Mass Range modifications (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using previously described methods70. The HCD voltage was set to 150 V, and the capillary temperature was increased to 300 °C. Denatured intact LC-MS was performed on EmbB in DDM using a SolariX FTICR mass spectrometer (Bruker). The online LC separation was performed using a BioResolve RP mAB polyphenyl, 450 Å, 2.7 µM, 2.1 × 100 mm column (Waters) with the column temperature at 65 °C. The gradient was adjusted over 38 min from water to acetonitrile, each with 0.1% formic acid. The protein eluted at around 30/70 water/acetonitrile. For both native and denatured mass spectra, data were deconvolved and analyzed using UniDec71. Uncertainties were derived from the weighted standard deviation of masses measured at different charge states.

Screening, imaging, and data analysis of the glycan array

Glycan array analysis was done with M. smegmatis EmbB protein solubilized in DDM. Slides were prewetted in buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 0.05% Tween 20) for 5 min, rinsed with buffer B (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2) three times, and blocked overnight with buffer C (1% BSA in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 0.15 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2) at 4 °C. Aliquots (500 μL) of serial dilutions of protein samples in buffer C were transferred to wells of the slide module immediately after aspiration of the blocking buffer. Wells were sealed with an adhesive seal and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Protein was removed by aspiration, and slides were washed 10 times with buffer A and three times with buffer B. Fluorescence was measured directly or after addition of a secondary antibody in buffer C (1:1000 dilution). Slides were incubated with a secondary antibody at room temperature for 40 min before being washed repeatedly with buffer A and deionized water.

Before being scanned, slides were dried by centrifugation. Microarrays were scanned at 5-μm resolution with a GenePix 4000B scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The fluorescent signal was detected at 532 nm for Cy3 or Alexa Fluor 555 and 488 nm for Alexa Fluor 488. The laser power was 100%, and the photomultiplier tube gain was 400. The fluorescent signals were analyzed by quantifying the pixel density (intensity) of each spot using GenePix ProMicroarray Image Analysis Software version 6.1. Fluorescence intensity values for each spot and its background were calculated. The local background signal was automatically subtracted from the signal of each separate spot, and the mean signal intensity of each spot was used for data analysis. Averages of triplicate experiments and standard deviations were calculated using Microsoft Excel.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Christina Chen for help with nanodisc incorporation, Khuram Ashraf for help with expression optimization, Jonathan Kim for help with purifications, Vasileios Petrou for helpful discussions and Leora Hamberger for her assistance managing the Mancia laboratory (Columbia University). We thank Ed Eng, Bill Rice, Laura Kim, Mikhail Kopylov, and Kelsey Jordan (New York Structural Biology Center, Simons Electron Microscopy Center) for help with microscope setup. We thank Sargis Dallakyan, Carl Negro, Shaker Krit and Swapnil Bhatkar (New York Structural Biology Center, Simons Electron Microscopy Center) for computation support. We thank Dr. Krishna Parsawar and the University of Arizona Analytical & Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility for help with the FTICR mass spectrometer. This work was supported by grants from NIH (R35 GM128624 to M.T.M., R01 GM111980, R35 GM132120, and R21 AI119672 to F.M., P41 GM103310 and OD019994 to C.S.P. and B.C.), Agency for Science, Technology and Research Singapore (to Y.Z.T.), University of Alabama at Birmingham (to M.N.), Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal (PD/BD/128261/2016 to J.R.; PTDC/BIA-BQM/30421/2017 and IF/00656/2014 to M.A.), EU H2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant No 823780 and Instruct-ULTRA (No 731005), an EUH2020 project to further develop the services of Instruct-ERIC (to J.R. and M.A.), Simons Foundation (SF349247 to C.S.P., B.C.), NYSTAR (to C.S.P., B.C.), Agouron Institute (F00316 to C.S.P., B.C.) and the Canadian Glycomics Network (to T.L.L.). Some of the work was performed at the Center for Membrane Protein Production and Analysis (COMPPÅ; P41 GM116799 to Wayne Hendrickson) and at the National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy at the Simons Electron Microscopy Center (P41 GM103310), both located at the New York Structural Biology Center. M.A. acknowledges MostMicro Research Unit (financially supported by LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-007660 funded by FEDER funds through COMPETE2020 and by national funds through FCT), and iNOVA4Health (LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-007344, co-funded by FEDER under PT2020).

Author contributions

F.M. and O.B.C. conceived the study. B.K., A.L.R., and J.R. performed the cloning and small-scale screening. Y.Z.T. did the expression and purification with S.I.G.’s help. Y.Z.T. did the negative stain EM and cryo-EM. Y.Z.T. built the model with O.B.C.’s help. J.E.K. and M.T.M. did the mass spectrometry. R.B.Z. did the glycan array experiments and R.B. synthesized potential acceptor substrates under T.L.L.’s supervision. L.Z., M.N., and M.A. gave input throughout the project. B.C. and C.P. supervised EM analysis. F.M. supervised the entire project. Y.Z.T. and F.M. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Data availability

All raw movie frames, micrographs, the particle stack and relevant metadata files has been deposited into EMPIAR72 as EMPIAR-10420. The electron density map has been deposited into EMDB73 as EMD-21983. The model has been deposited into PDB74 as 6X0O [10.2210/pdb6X0O/pdb]. All other data are available in the paper or the supplementary materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bridget Carragher, Email: bcarr@nysbc.org.

Filippo Mancia, Email: fm123@cumc.columbia.edu.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-17202-8.

References

- 1.Jankute M, Cox JA, Harrison J, Besra GS. Assembly of the mycobacterial cell wall. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;69:405–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrahams KA, Besra GS. Mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis: a multifaceted antibiotic target. Parasitology. 2018;145:116–133. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016002377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grzegorzewicz, A. E. et al. Assembling of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall core. J. Biol. Chem.291, 18867–18879 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Wolucka BA, McNeil MR, de Hoffmann E, Chojnacki T, Brennan PJ. Recognition of the lipid intermediate for arabinogalactan/arabinomannan biosynthesis and its relation to the mode of action of ethambutol on mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23328–23335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telenti A, et al. The emb operon, a gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis involved in resistance to ethambutol. Nat. Med. 1997;3:567–570. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escuyer VE, et al. The role of the embA and embB gene products in the biosynthesis of the terminal hexaarabinofuranosyl motif of Mycobacterium smegmatis arabinogalactan. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48854–48862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caminero JA, Sotgiu G, Zumla A, Migliori GB. Best drug treatment for multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010;10:621–629. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field SK, Cowie RL. Treatment of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex lung disease with a macrolide, ethambutol, and clofazimine. Chest. 2003;124:1482–1486. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safi H, et al. Evolution of high-level ethambutol-resistant tuberculosis through interacting mutations in decaprenylphosphoryl-β-D-arabinose biosynthetic and utilization pathway genes. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1190. doi: 10.1038/ng.2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amin AG, et al. EmbA is an essential arabinosyltransferase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology. 2008;154:240. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012153-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alderwick, L. J. et al. The C-terminal domain of the arabinosyltransferase Mycobacterium tuberculosis EmbC is a lectin-like carbohydrate binding module. PLoS Pathog.7, e1001299 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Zhang, L. et al. Structures of cell wall arabinosyltransferases with the anti-tuberculosis drug ethambutol. Science368, 1211–1219 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Love J, et al. The New York Consortium on Membrane Protein Structure (NYCOMPS): a high-throughput platform for structural genomics of integral membrane proteins. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics. 2010;11:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s10969-010-9094-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Mushegian A. Three monophyletic superfamilies account for the majority of the known glycosyltransferases. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1418–1431. doi: 10.1110/ps.0302103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan, Y. Z. et al. Cryo-EM structures and regulation of arabinofuranosyltransferase AftD from mycobacteria. Mol. Cell78, 683–699 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Petrou VI, et al. Structures of aminoarabinose transferase ArnT suggest a molecular basis for lipid A glycosylation. Science. 2016;351:608–612. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai L, Kovach A, You Q, Kenny A, Li H. Structure of the eukaryotic protein O-mannosyltransferase Pmt1–Pmt2 complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019;26:704–711. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0262-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Napiórkowska M, et al. Molecular basis of lipid-linked oligosaccharide recognition and processing by bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:1100. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seidel M, Alderwick LJ, Sahm H, Besra GS, Eggeling L. Topology and mutational analysis of the single Emb arabinofuranosyltransferase of Corynebacterium glutamicum as a model of Emb proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Glycobiology. 2007;17:210–219. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korkegian A, Roberts DM, Blair R, Parish T. Mutations in the essential arabinosyltransferase EmbC lead to alterations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:35172–35181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.583112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lairson, L., Henrissat, B., Davies, G. & Withers, S. Glycosyltransferases: structures, functions, and mechanisms. Ann. Rev. Biochem.77, 521–555 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Berg S, et al. Roles of conserved proline and glycosyltransferase motifs of EmbC in biosynthesis of lipoarabinomannan. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5651–5663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiaradia L, et al. Dissecting the mycobacterial cell envelope and defining the composition of the native mycomembrane. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12718-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan PJ, Nikaido H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995;64:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holm L, Laakso LM. Dali server update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W351–W355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng RB, et al. Insights into interactions of mycobacteria with the host innate immune system from a novel array of synthetic mycobacterial glycans. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:2990–3002. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sreevatsan S, et al. Ethambutol resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: critical role of embB mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1677–1681. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramaswamy SV, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of nucleotide polymorphisms associated with ethambutol resistance in human isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:326–336. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.326-336.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goude R, Amin A, Chatterjee D, Parish T. The arabinosyltransferase EmbC is inhibited by ethambutol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4138–4146. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00162-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lety M, Nair S, Berche P, Escuyer V. A single point mutation in the embB gene is responsible for resistance to ethambutol in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2629–2633. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beggs WH, Andrews FA. Chemical characterization of ethambutol binding to Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1974;5:234–239. doi: 10.1128/aac.5.3.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.OFFICIAL T. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990;142:940–953. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lan Z, Bastos M, Menzies D. Treatment of human disease due to Mycobacterium bovis: a systematic review. Eur. Respiratory J. 2016;48:1500–1503. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00629-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panteix G, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium microti: a study of six recent cases in France. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010;59:984–989. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.019372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rastogi N, Goh KS, Bryskier A, Devallois A. Spectrum of activity of levofloxacin against nontuberculous mycobacteria and its activity against the Mycobacterium avium complex in combination with ethambutol, rifampin, roxithromycin, amikacin, and clofazimine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2483–2487. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Soolingen D, et al. A novel pathogenic taxon of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Canetti: characterization of an exceptional isolate from Africa. Int. J. Syst. Evolut. Microbiol. 1997;47:1236–1245. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiloh MU, Champion PAD. To catch a killer. What can mycobacterial models teach us about Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010;13:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenthal PB, Henderson R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:721–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapopoulou A, Lew JM, Cole ST. The MycoBrowser portal: a comprehensive and manually annotated resource for mycobacterial genomes. Tuberculosis. 2011;91:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high‐quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol.7, 539 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Robert X, Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruni R, Kloss B. High-throughput cloning and expression of integral membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 2013;74:29.26. 21–29.26. 34. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps2906s74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stols L, et al. New vectors for co-expression of proteins: structure of Bacillus subtilis ScoAB obtained by high-throughput protocols. Protein Expr. Purif. 2007;53:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bayburt TH, Sligar SG. Membrane protein assembly into Nanodiscs. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1721–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suloway C, et al. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;151:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lander GC, et al. Appion: an integrated, database-driven pipeline to facilitate EM image processing. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;166:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SH, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. Elife. 2016;5:e18722. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng A, et al. High resolution single particle cryo-electron microscopy using beam-image shift. J. Struct. Biol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang K. Gctf: real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 2016;193:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rice WJ, et al. Routine determination of ice thickness for cryo-EM grids. J. Struct. Biol. 2018;204:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Punjani, A., Zhang, H. & Fleet, D. J. Non-uniform refinement: Adaptive regularization improves single particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Preprint at 10.1101/2019.12.15.877092 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Grant T, Rohou A, Grigorieff N. cisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. Elife. 2018;7:e35383. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terwilliger, T. C., Ludtke, S. J., Read, R. J., Adams, P. D. & Afonine, P. V. Improvement of cryo-EM maps by density modification. Preprint at 10.1101/845032 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. computational Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Afonine, P. V. et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr.74, 531–544 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barad BA, et al. EMRinger: side chain–directed model and map validation for 3D cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:943. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cardone G, Heymann JB, Steven AC. One number does not fit all: mapping local variations in resolution in cryo-EM reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 2013;184:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan YZ, et al. Addressing preferred specimen orientation in single-particle cryo-EM through tilting. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:793. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baldwin, P. R. & Lyumkis, D. Non-uniformity of projection distributions attenuates resolution in cryo-EM. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol.150, 160–183 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Voss NR, Gerstein M. 3V: cavity, channel and cleft volume calculator and extractor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W555–W562. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ashkenazy H, et al. ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W344–W350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Townsend JA, Keener JE, Miller ZM, Prell JS, Marty MT. Imidazole derivatives improve charge reduction and stabilization for native mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:14765–14772. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marty MT, et al. Bayesian deconvolution of mass and ion mobility spectra: from binary interactions to polydisperse ensembles. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:4370–4376. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iudin A, Korir PK, Salavert-Torres J, Kleywegt GJ, Patwardhan A. EMPIAR: a public archive for raw electron microscopy image data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:387. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lawson CL, et al. EMDataBank unified data resource for 3DEM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D396–D403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Berman H, Henrick K, Nakamura H, Markley JL. The worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB): ensuring a single, uniform archive of PDB data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D301–D303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dulberger, C. L., Rubin, E. J. & Boutte, C. C. The mycobacterial cell envelope—a moving target. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.18, 47–59 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Mishra AK, Driessen NN, Appelmelk BJ, Besra GS. Lipoarabinomannan and related glycoconjugates: structure, biogenesis and role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and host–pathogen interaction. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011;35:1126–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw movie frames, micrographs, the particle stack and relevant metadata files has been deposited into EMPIAR72 as EMPIAR-10420. The electron density map has been deposited into EMDB73 as EMD-21983. The model has been deposited into PDB74 as 6X0O [10.2210/pdb6X0O/pdb]. All other data are available in the paper or the supplementary materials.