Abstract

Context

Advance care planning (ACP) is essential to elicit goals, values, and preferences of care in older adults with serious illness and on trajectories of frailty. An exploration of ACP uptake in older adults may identify barriers and facilitators.

Objective

To conduct an integrative review of research on the uptake of ACP in older adults and create a conceptual model of the findings.

Methods

Using Whittemore and Knafl's methodology, we systematically searched four electronic databases of ACP literature in older adults from 1996 through December 2019. Critical appraisal tools were used to assess study quality, and articles were categorized according to level of evidence. Statistical and thematic analysis was then undertaken.

Results

Among 1081 studies, 78 met inclusion criteria. Statistical analysis evaluated ACP and variables within the domains of demographics, psychosocial, disability and functioning, and miscellaneous. Thematic analysis identified a central category of enhanced communication, followed by categories of 1) provider role and preparation; 2) patient/family relationship patterns; 3) standardized processes and structured approaches; 4) contextual influences; and 5) missed opportunities. A conceptual model depicted categories and relationships.

Conclusions

Enhanced communication and ACP facilitators improve uptake of ACP. Clinicians should be cognizant of these factors. This review provides a guide for clinicians who are considering implementation strategies to facilitate ACP in real-world settings.

Key Words: Advance care planning, communication, patient- and family-centered, older adults, conceptual model

Introduction

“It's always too early, until it's too late,” the words of the Conversation Project describe the not uncommon end-of-life (EOL) planning for older adults. “Too late” often means that an older adult has encountered a crisis (fall, sudden illness, exacerbation) in which he/she is unable to relay or express personal preferences about EOL care, thus underscoring the need for advance care planning (ACP). ACP enables patients and their families to identify and plan the care and treatments that are acceptable to them and that are consistent with their personal values and preferences.1

The growing field of palliative care and the rapidly aging population underscore the importance of ACP, given longevity may be accompanied by serious illness, symptom burden, functional dependence and frailty, caregiver burden, and high health-care utilization.2 , 3 The Institute of Medicine's (IOM) 2014 Dying in America report emphasized the need for new models of care that promote ACP conversations.4 Despite the medical, legal, and pragmatic utility and benefits of ACP, uptake remains below 20%,5 and EOL communication is still lacking in all clinical settings, including long-term care.6 Discussing ACP with older adults who face the end of life with greater uncertainty is an underexplored area of research. While risk prediction and prognostication related to aging and frailty is difficult at the individual level, the need for ACP before a crisis event is paramount.

In light of the need to improve ACP efforts in health care for older patients with and without a serious illness and looming frailty, we wished to explore ACP efforts directed specifically at uptake in older adults. Other recent systematic reviews related to ACP in older adults address other facets including specific conditions (heart failure, cancer)7 , 8; attitudes, experiences, and perspectives of older adults9 , 10; and outcomes of ACP.11 , 12 One review addressed barriers and facilitators of ACP in an acute care setting, but the section was brief and reported from three studies.12 We sought to take a deeper dive to better understand approaches (or lack of) to ACP that influence uptake and completion of the ACP process. Such an exploration might provide insight for future research and clinical practice in this growing population. Thus, the specific aim of this encompassing integrative review was to explore the literature that describes uptake of ACP in older adults and to create a conceptual model of relationships leading to ACP outcomes. Within this review, we define uptake according to Merriam-Webster's definition as “making use of” or “an act of absorbing and incorporating”.13 ACP is defined as a process that supports adults at any age or health status in understanding and sharing their values, goals, and preferences regarding future medical care.14

Material and Methods

The integrative review methodology, introduced by Whittemore and Knafl,15 allows for the combination of qualitative and quantitative methodologies to inform evidence-based practice. Although randomized controlled trials remain the gold standard for determining the efficacy of interventions, other studies can shed light on other important considerations. Integrative reviews capture a broader perspective to more fully understand a phenomenon through the inclusion of observational and experimental research.15 An integrative approach was selected for this review because of the growing population of older adults who are reaching their 90s and 100s with and without overriding chronic conditions and frailty in the final phase of life. A broad examination of multiple research designs can strengthen our understanding of ACP in this population and inform future research and clinical practice.

Literature Search

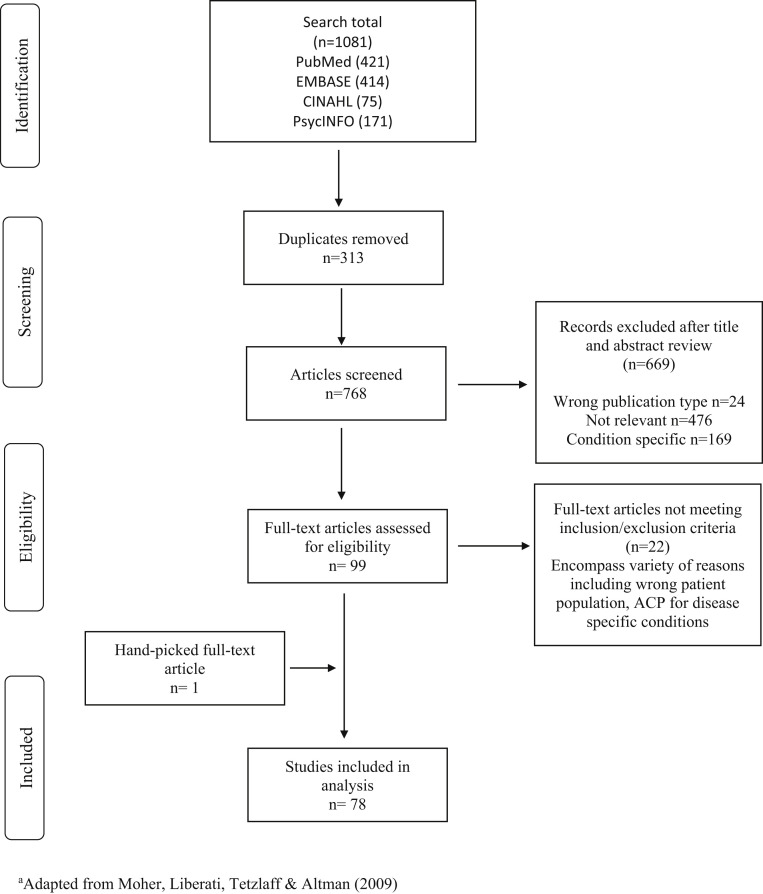

A search strategy was developed in collaboration with a coauthor medical librarian (R.L.W.). The search included MeSH terms: “advance care planning,” OR “advance directives,” OR “living wills,” AND “patient preferences,” OR “consumer participation,” OR “patient participation,” OR “personal autonomy” in multiple combinations. A filter of age 65 years and older was placed on each search. A comprehensive search was conducted through December 2019 in PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Embase (Figure 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram.a ACP = advance care planning.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) addressed three factors: a) components of ACP (advance directives, identification of healthcare proxy, discussions with patients, families, and health-care providers), b) ACP uptake, and c) older adults; 2) peer-reviewed; 3) published in English; 4) featured primary research (data collected directly by investigators); and 5) encompassed serious illness, including frailty. Exclusion criteria included 1) published in a non-English language; 2) opinion articles, study protocols, case studies, and conference abstracts; 3) systematic reviews; and 4) focused on ACP for specific disease entities such as cancer, dementia, or congestive heart failure. The decision to exclude specific diseases was intentional and prognostication-related as ACP approaches differ between older adults with clear terminal conditions (i.e., heart failure, cancer) and those who are on trajectories of frailty and facing the end of life with greater uncertainty. We were most interested in ACP uptake in cases of uncertainty. Seventy-seven studies were preliminarily included in the review, with one additional study added from a subsequent hand search of references.

Data Evaluation and Analysis

An integrative design and synthesis approach was used to evaluate studies in an inductive stepwise process, including 1) quality appraisal of studies using critical appraisal tools, 2) extraction of descriptive content and rating of evidence (levels) with the research hierarchy,16 3) analysis of applicable statistical results (effect sizes) of factors (variables) that influence ACP as a dependent variable, and 4) content analysis of results to identify categories, defined themes, and descriptors within studies. Our approach allowed for the study findings to move beyond a summary used in a narrative review to an approach used to generate new insights and understanding of ACP uptake in a broad, yet systematic, manner.17

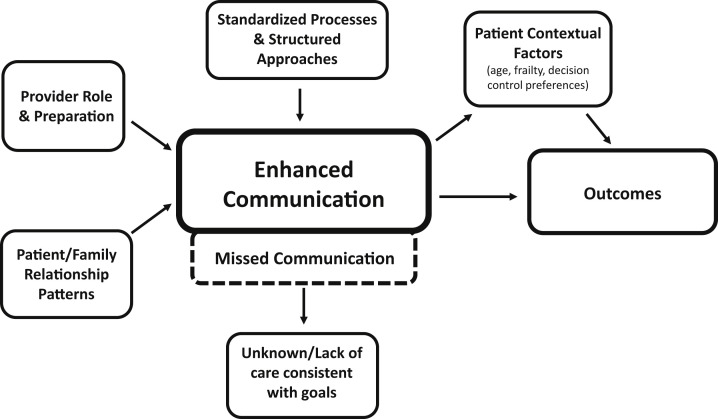

Quality appraisal of studies was conducted using Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for analytical cross-sectional, quasi-experimental, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and qualitative studies.18 Studies were examined to determine the extent to which each met appraisal criteria, noting limitations that might influence the accuracy of study findings (Appendix I). Data were reviewed by two independent researchers (E.F. and C.A.M.), and disagreements were resolved through discussion. In the second step, data were extracted from each study, and evidence tables were developed which included study objective(s), level of evidence, setting and location, sample and participant characteristics, study design and data collection methods, ACP uptake features/factors, and ACP uptake outcome (Appendix II). Results from studies comprising quantitative analyses from which effect sizes could be generated were categorized into key sets including 1) demographic variables, 2) psychosocial variables, 3) variables related to physical function/disability, and 4) other variables (i.e., targeted interventions, process facilitators). To extract categories and themes from studies, results sections of all studies containing a qualitative analysis were line-by-line coded for factors contributing, negatively or positively, to uptake of ACP. In the fourth step, categories were developed; themes from all 78 studies were defined and organized under each category, and descriptors from each study were placed in tables (Appendix III). From the tables of categories, themes and descriptors, an integrated conceptual model was developed (Figure 2 ) that provides a broad visual depiction of the major categories and relationships.15

Fig. 2.

Communication in advance care planning conceptual model.

Results

Summary of Descriptive Data and Evidence Levels

Seventy-eight studies (1996–2019) met inclusion criteria. The review included 23 qualitative, five mixed-methods and 50 quantitative studies (including 12 RCTs). Studies were conducted in 13 countries: United States n = 40, Canada n = 10, Australia n = 7, Hong Kong n = 3, Taiwan n = 1, United Kingdom n = 4, Norway n = 2, Germany n = 2, Belgium n = 3, South Korea n = 1, Japan n = 1, Sweden n = 1, and Netherlands n = 2. One study represented 11 countries as a whole, but results were not reported by country. Sample sizes for the 78 studies included qualitative (range: 719 to 50320), mixed-methods (range: 2121 to 28922), and quantitative (range: 1823-25,55024). The 12 RCT sample sizes ranged from 1425 to 2294.26 Details of age range, gender, and race/ethnicity of participants are shown in Appendix II.

Evidence Levels

Within the rating system for the hierarchy of evidence for treatment outcomes,27 , 28 12 studies were level II (well-designed RCTs); one study was level III (controlled trial without randomization); 37 studies were level IV (case control, cohort studies); and 28 studies were level VI (descriptive or qualitative).

Summary of Relevant Statistical Results

Statistical Results

A critical analysis and synthesis of methods, measurement tools, and statistical techniques to study the phenomenon was undertaken. For brevity, major findings are reported in this narrative with specific effect sizes in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 . Studies that were included specifically aligned with the ACP consensus definition, with ACP being the dependent outcome variable with the independent variables represented through domains of demographics, psychosocial, disability and functioning, and miscellaneous.

Table 1.

Effect Sizes for the Association of Demographic Characteristics With ACP

| Characteristic | Unadjusted O.R. | Adjusted O.R. | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing age | |||

| Continuous | 1.31 | N/A | 29 |

| Continuous | AD: 0.90 POA: 0.88 |

N/A | 32a |

| Continuous | AD + Discussion: 2.22 Discussion only: 1.39 |

N/A | 30 |

| Continuous | 1.01 | N/A | 31 |

| Continuous | N/A | 1.1 | 37 |

| 18-64 vs. ≥85 | 1.76 | N/A | 33 |

| Gender, maleb vs. female | |||

| 0.93 | N/A | 29 | |

| AD + Discussion: 0.60 Discussion only: 1.14 |

N/A | 30 | |

| AD: 1.08 POA: 1.13 |

N/A | 32 | |

| 0.62 | N/A | 31 | |

| N/A | 0.77 | 34 | |

| 1.08 | N/A | 33 | |

| Race/ethnicity, whiteb | |||

| Ethnic/racial minorityb | AD + Discussion: 1.09 Discussion only: 0.37 |

N/A | 30 |

| African Americanb | N/A | 2.00 | 37 |

| Hispanicb | 1.00 | ||

| American Indian, Asianb | 1.40 | ||

| African Americanb | 1.29 | N/A | 38 |

| Marital status, not marriedb vs. married | |||

| 1.35 | N/A | 29 | |

| AD + Discussion: 1.84 Discussion only: 1.28 |

N/A | 30 | |

| AD: 1.07 POA: 1.13 |

N/A | 32 | |

| N/A | 1.00 | 37 | |

| Increasing education | |||

| <H.S.b vs. H.S. | N/A | 1.63 | 29 |

| <H.S.b vs. > H.S. | 3.90 | 2.40 | 29 |

| Continuous | AD + Discussion: 3.37 Discussion only: 1.72 |

N/A | 30 |

| Continuous | AD: 1.58 POA: 1.25 |

N/A | 32 |

| <Elementaryb vs. >H.S. | 0.80 | N/A | 33 |

| Place of residence | |||

| Institutionalb vs. private | AD: 0.66 POA: 0.53 |

N/A | 32 |

| Institutionalb vs. private | 0.54 | N/A | 29 |

ACP = Advance care planning; AD = advance directives.

To be included in this study, participants had to be older than 75 years.

The category (for categorical independent variables) that was the referent category in the analysis.

Table 2.

Effect Sizes for the Association of Psychosocial Characteristics With ACP

| Characteristic | Unadjusted O.R. | Adjusted O.R. | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living situation and social support | |||

| Lives w/othersa vs. alone | 1.61 | N/A | 29b |

| Increasing social support | |||

| Someone to listen | 6.93 | N/A | 29 |

| Emotional support | 2.83 | N/A | 29 |

| Increased perceived health | |||

| Lowa vs. good | 1.01 | N/A | 29 |

| Lowa vs. excellent | 1.09 | N/A | 29 |

| Lowa vs. good/better | AD + Discussion: 1.90 Discussion only: 1.77 |

N/A | 30 |

| Continuous | AD: 0.90 POA: 1.06 |

N/A | 32 |

| Quality of life, unable to care for selfa | |||

| Some problems | N/A | 6.11 | 31 |

| No problems | 3.65 | ||

| Increased marital support | |||

| Continuous | AD + Discussion: 1.04 Discussion only: 1.72 |

N/A | 30 |

| Higher general family functioning | |||

| Continuous | AD + Discussion: 1.69 Discussion only: 1.99 |

N/A | 30 |

| Increasing number of children | |||

| Continuous | AD + Discussion: 0.58 Discussion only: 0.88 |

N/A | 30 |

| Increased support from children | |||

| Continuous | AD + Discussion: 1.10 Discussion only: 1.39 |

N/A | 30 |

| Increased religiosity/spirituality | |||

| Importance (continuous) | N/A | 1.32 | 35 |

| Influence medical (continuous) | 2.25 | 35 | |

| Decreased depressive symptoms | |||

| Higha vs. low | 2.31 | N/A | 29 |

| Continuousc | AD + Discussion: 1.40 Discussion only: 1.50 |

N/A | 30 |

| Higha vs. low | AD: 1.24 POA: 0.93 |

N/A | 32 |

| Precursors: personal preferences | |||

| Decision control preferences: lowa vs. high | Surrogate decision-maker: 0.93 Completed AD: 1.33 Made decision for self: 1.79 Made decision for others: 2.00 |

N/A | 36 |

| Wish to be informed of diagnosis of terminal disease, noa vs. yes | N/A | 9.19 | 31 |

ACP = advance care planning; AD = advance directives.

The category (for categorical independent variables) that was the referent category in the analysis.

Unique community-dwelling older adult (mean age 88 years) population.

Original OR = 0.72 and 0.69 indicating higher depression, less likelihood. These were inverted for consistency with the other ORs in this section (lower depression, increased likelihood).

Table 3.

Effect Sizes for the Association of Disability and Functioning With ACP

| Characteristic | Unadjusted O.R. | Adjusted O.R. | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning, ADL/IADLa | |||

| ≥1 ADLa vs. None | 1.79 | N/A | 29 |

| Continuous, higher score, fewer ADLsa | AD: 0.91 POA: 1.09 |

N/A | 32 |

| Continuous, higher score, fewer IADLa | AD: 0.91 POA: 0.91 |

N/A | 32 |

| Physical functioning, ability to walk half a milea | |||

| Unablea vs. able | 1.88 | N/A | 29 |

| Physical functioning, use of assistive device to perform ADLa | |||

| Noa vs. yes | 0.76 | N/A | 29b |

| Noa vs. yes | AD + Discussion: 1.20 Discussion only: 1.26 |

N/A | 30 |

| Increasing frailty | |||

| Continuous | AD: 1.00 POA: 1.00 |

N/A | 32 |

| Cognitive functioning | |||

| Lowa vs. high | 1.57 | N/A | 29 |

| Self-report: memory worsea vs. same | AD: 1.02 POA: 0.94 |

N/A | 32 |

| MMSE, low - >higha | AD: 1.60 POA: 1.60 |

N/A | 32 |

| Comorbid illness | |||

| Nonea vs. 1 | 0.78 | N/A | 29 |

| Nonea vs. 2 | 0.89 | N/A | 29 |

| Nonea vs. 3 | 0.68 | N/A | 29 |

| Increasing number (continuous) | N/A | 1.30 | 37 |

| Nonea vs. >1 | N/A | 1.82 | 38 |

| Nonea vs. stroke | N/A | 0.33 | 33 |

| Use of health-care services | |||

| Nonea vs. ≥2 hospitalizations | 1.08 | N/A | 29 |

| Nonea vs. ≥2 outpatient visits | 1.16 | N/A | 29 |

| Noa vs. nursing home stay | 2.20 | N/A | 29 |

| Continuous (# inpatient services) | N/A | 0.80 | 37 |

| Continuous (# outpatient services) | N/A | 1.80 | 37 |

ACP = advance care planning; AD = advance directives; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

The category (for categorical independent variables) that was the referent category in the analysis.

Unique community-dwelling older adult (mean 88 years old) population.

Table 4.

Effect Sizes From Implementation and Clinical Trial studies Investigating Document and Process Facilitators Effect on ACP

| Characteristic | Unadjusted O.R. | Adjusted O.R. | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitation of document completion | |||

| Controla vs. intervention | 3.20 | N/A | 26 |

| Controla vs. Intervention | 2.17 | N/A | 39 |

| Controla vs. Intervention | 23.27 | N/A | 40 |

| Facilitation of process | |||

| Single group, prea vs. post | 22.00 | N/A | 41 |

| Controla vs. intervention | 3.82 | 4.52 | 43 |

| Controla vs. intervention | 2.61 | N/A | 42 |

| Controla vs. intervention | Documentation: 17.14 Discussions: 5.60 |

N/A | 44 |

The category (for categorical independent variables) that was the referent category in the analysis.

Demographics

Demographic variables analyzed for their effects on ACP included age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and place of residence. Most studies reported that the likelihood of engaging in ACP increased with increasing age (ORs = 1.01 to 2.22).29, 30, 31 Gender demonstrated generally mixed effects (ORs = 0.60 to 1.14)29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34; however, being married increased likelihood of ACP as compared to not being married (OR = 1.07 to 1.84).29 , 30 , 32 Higher levels of education were most commonly associated with increased likelihood of ACP (OR = 1.25 to 3.90),29 , 30 , 32 and one study reported the effect after adjusting for other demographic variables (OR = 1.63 and 2.40).29 Living in a private setting, compared to an institutional setting, dramatically reduced the likelihood of ACP (OR = 0.53 to 0.66)32 (Table 1).

Psychosocial

Results from studies of psychosocial variable effects on ACP uptake are summarized in Table 2. Those variables have included living situation, social support, perceived health, quality of life, nature of marital relationship, general family functioning, number of children, relationship with children, religiosity/spirituality, presence of depressive symptoms, and personal preferences. Social support, described as having someone to listen and provide emotional support, was associated with increased likelihood of ACP (someone to listen, OR = 6.93; someone to provide emotional support, OR = 2.83).30 If grouped into categories (good/better/excellent vs. poor), the likelihood of ACP generally was reported to increase with better perceptions of health (OR = 1.01 to 1.90).29 , 30 Higher family functioning, or the degree to which families function as a unit, was associated with increased likelihood of ACP (OR = 1.69 and OR = 1.99),30 as was increased emotional support from adult children (OR = 1.10, 1.39),30 yet the likelihood of ACP tended to decrease as the number of children increased (OR = 0.58, 0.88).30 Other psychosocial variables including religiosity/spirituality were associated with increased likelihood of ACP even when adjusted for religious affiliation, degree of religiosity or spirituality, beliefs, values, sociodemographic, and health status (ORs = 1.32, 2.25).35 Decreased or absent depressive symptoms were consistently associated with increased likelihood of ACP (OR = 1.24 to 2.31).29 , 30 , 32 A couple of studies looked at the effects of personal preferences as precursor variables (decision control preferences36 and wish to be informed of diagnosis of terminal disease31) on the likelihood of ACP. Generally, higher decision control preferences increased the likelihood of ACP (OR = 0.93 to 2.00),36 while the wish to be informed increased the likelihood after adjusting for age and gender (OR = 9.19)31 (Table 2).

Disability and Functioning

Disability and functioning variables included physical functioning, frailty, cognitive functioning, comorbidity, stroke, and the use of health-care services. As shown in Table 3, associations of physical functioning with ACP were mixed, yet most studies reported an increased likelihood of ACP with better functioning (OR = 1.79, 1.88,29 OR = 1.20–1.2630).

Increased cognitive functioning (higher Mini-Mental State Examination scores) was generally associated with increased likelihood of ACP (OR = 1.57;29 OR = 1.6032). After adjusting for age, sociodemographics, and other pertinent variables, studies generally found that the likelihood of ACP increased with increasing comorbidities (OR = 1.30, 1.82)37 , 38 (Table 3).

Other Variables

Several studies, as shown in Table 4, investigated the effect of specific programs/variables on engagement in ACP using implementation and clinical trial designs. Generally targeted interventions increased engagement outcomes (multifaceted, OR = 2.17;39 electronic motivational prompts, OR = 3.20;26 defined ACP program [Respecting Choices], OR = 23.2740), as did those that focused on process facilitators (decision aids, OR = 22.0,41 OR = 2.61;42 standardized templates, OR = 3.82;43 and online ACP program [PREPARE], OR = 17.14 [documentation], OR = 5.6 [discussions])44 (Table 4).

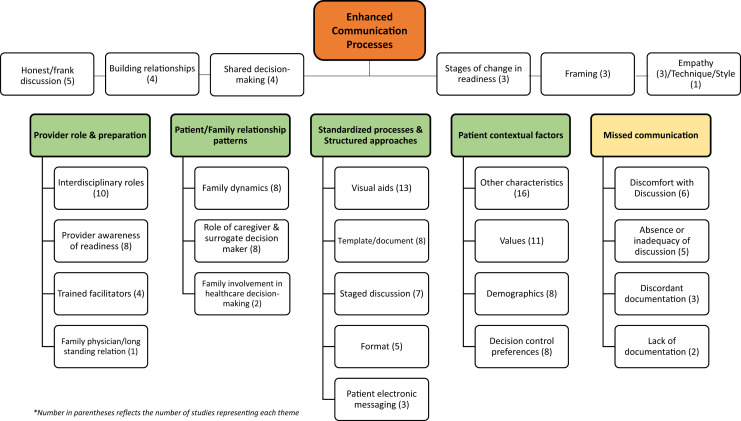

Thematic Analysis

Line-by-line coding of factors associated with uptake of ACP was conducted by two investigators (E.F. and C.A.M.). Codes were organized to allow for translation of concepts/ideas from one study to another and for grouping of codes into categories, themes, and descriptors. Figure 3 provides an overview of the categories and themes derived from this process. A detailed breakdown of the process with groupings is reported in Appendix III. The analysis includes 27 thematic tables with studies (author/year) and descriptors related to the theme. From this process of analysis, we developed a conceptual model (Figure 2) that provides a high-level overview of our results. The following section presents our findings based on the conceptual model with a focus on the categories and themes represented under each category.

Fig. 3.

Categories and themes diagram.

Enhanced Communication Processes

The category of enhanced communication processes emerged as the central requisite addressed in some way in every study for successful ACP and improved outcomes. The term “enhanced” conveys the necessity of additional factors/traits required to move beyond the status quo.45 These requirements are represented by themes of honest/frank discussion,20 , 46, 47, 48, 49 building personal relationships,20 , 50, 51, 52 shared decision-making,30 , 47 , 53 , 54 stages of change in terms of readiness,20 , 55 , 56 framing,43 , 57, 58, 59 empathy,20 , 49 , 60 and technique/style.21

Five studies20 , 46, 47, 48, 49 reported the importance of honest/frank discussion in ACP with a focus on the delivery of truthful information. The concept of “conditional candour” in one study described a preference for frank information while also assessing readiness,48 and another highlighted the necessity for physicians to communicate through an honest and straightforward approach while continuing to be attentive to patients' informational and emotional needs.49 Another theme to emerge was that of building relationship and forming a connection or bond between two or more parties.20 , 50, 51, 52 The importance of building a relationship extended to both patients and surrogate decision-makers, highlighting engagement in ACP as a dyadic activity,52 with the surrogate being the one who knew the older adult best and would ensure their treatment was in accordance with values.51 The importance of being “known” by a provider was noted as critical to the ease of ACP discussions and honoring preferences.50

Shared decision-making is reported as a way to support and maintain individual patient autonomy while requiring skilled providers to seek permission and respect patient communication and patient engagement.30 , 47 , 53 , 54 Another approach focused on the assessment of readiness for change in participants as a factor for modifying/adapting individual approaches.20 , 55 , 56 Recognition of ACP as specific behaviors in which individuals progress through stages of change or readiness has been explored by Fried et al. and grounded in the Transtheoretical Model of behavior change.61

Provider Role and Preparation

The role of the provider in approaching conversations with patients about the end of life is key, as is recognition that conversations are often emotionally charged and require preparation. Health-care providers have a responsibility to assist in the decision-making process through education about ACP and communication skills that impart compassion and empathy.45 The specific roles and necessary preparation of health-care providers is critical for the uptake of ACP and the timing of ACP to occur within a framework that emphasizes responsiveness to patient and family emotions, while also focusing on overall goals of a patient's care.45 The category of provider role and preparation is supported by four themes, including interdisciplinary roles,23 , 33 , 39 , 43 , 59 , 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 provider awareness of readiness,19 , 22 , 36 , 46 , 48 , 65, 66, 67 trained facilitators,23 , 33 , 40 , 57 and a long-standing relation with a family physician.22 Ten studies reported the use of interdisciplinary team members as part of a study protocol to deliver ACP education, assess ACP knowledge, lead ACP meetings, and complete care planning documents.23 , 33 , 39 , 43 , 59 , 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 Four studies used a social worker to conduct ACP during home visits or an office visit before the scheduled provider visit,23 , 39 , 62 , 63 noting that the social workers' professional role of counseling and facilitative communication is a natural fit for ACP. Nurses' role in ACP is represented in five studies23 , 43 , 59 , 64 , 65 through a nurse facilitator to guide participants toward sharing and expressing their EOL wishes43 to a nurse-led interactive educational workshop64 and advance practice registered nurses' leading conversations following a Respecting Choices model.23

The theme of provider awareness of readiness was represented with 8 studies19 , 22 , 36 , 46 , 48 , 65, 66, 67 reporting the need for providers to understand patients/families' desire or lack of desire to engage in a conversation about EOL. The concept of readiness was further demonstrated in these studies through 1) patients' readiness to ask questions to doctors and participate in question-asking behaviors,36 2) increasing readiness to discuss EOL issues,46 3) timing of readiness when one is cognitively intact and has the ability to communicate wishes,65 and 4) the readiness to invite family to be part of the conversations as they know the patient's life story.19 The importance of sharing information when people are mentally prepared to receive it was stressed as otherwise it may be detrimental to a patient's emotional welfare or the patient-physician relationship.48

Patient/Family Relationship Patterns

The category of patient/family relationship patterns is supported by three themes of family dynamics,19 , 29 , 30 , 52 , 57 , 58 , 68 , 69 family involvement in health-care decision-making,38 , 70 and the role of caregiver and surrogate decision-maker.25 , 52 , 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 , 76 Eight studies highlighted the importance of understanding patterns of how patients and family members relate to one another.19 , 29 , 30 , 52 , 57 , 58 , 68 , 69 These studies characterized how family relations influence ACP through emotionally supportive or critical relationships.30 Family member involvement in care plan meetings where they were “moral witnesses to a key transition in the patient's life course”68 was invaluable to understanding how long-lasting family dynamics and relationship patterns held true in ACP.69 The participation of family in discussions was also noted to be a crucial factor, emphasizing the importance of including family whenever possible29 , 57 and recognizing the perception of patients and relatives as an “intertwined unit.”19

Standardized Processes and Structured Approaches

The category of standardized processes and structured approaches to ACP included the following themes: the use of visual aids,25 , 39 , 41, 42, 43, 44 , 49 , 55 , 62 , 64 , 77, 78, 79 template/document for ACP,23 , 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86 staged discussion,20 , 24 , 58 , 60 , 62 , 87 , 88 format of ACP discussion,60 , 64 , 78 , 89 , 90 and patient electronic messaging.26 , 91 , 92 Standardized and structured approaches build in or incorporate defined processes for older adults to receive ACP materials (information and documents) and allot time to enhance their understanding. These approaches also make the point of the need for documentation of discussions by health-care providers.

Patients make increasingly complex decisions about their medical care in ACP, underscoring the need for decision aids or additional information to increase understanding. Research has led to the development of aids that facilitate health-care decision-making by patients and families and improve the way physicians or providers present information.93 Five studies reported the use of an ACP workbook or booklet that was personalized to reflect life stories, patient views, and preferences.39 , 43 , 49 , 62 , 64 Four studies used a video decision aid which allows for a visual representation medium that engages patients in a way that verbal descriptions, whether written or oral, do not.25 , 41 , 42 , 78 Other visual aids include ACP through pictures, story boards, and media extracts,79 a “Go Wish” card game,77 an individualized feedback report,55 and a patient-facing interactive online ACP program.44

Patient Contextual Influences

Prior work has shown that in addition to structural constraints of health-care and legal systems, contextual factors that influence the uptake of ACP are complex and multifaceted and span the social and cultural beliefs of patients, families, and health professionals.94 Contextualization acknowledges that other factors that influence uptake of ACP exist for every person. This review encompassed a variety of other factors29 , 30 , 35 , 95, 96, 97 including frailty,40 , 73 , 98 culturally sensitive care,38 , 43 , 44 , 64 , 80 attitudinal differences,32 , 54 one's own values,77 , 99 , 100 demographic characteristics,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 , 37 , 38 and decision control preferences.20 , 36 , 47 , 53 , 54 , 67 , 72 , 88 The condition of frailty was represented in three studies40 , 73 , 98 using validated instruments to assess patients' degree of frailty. The trajectory of frailty can occur over months or years but ultimately predicts poor outcomes that lead to eventual death. Frailty is an important consideration as many older adults will experience frailty or progressive dwindling, may be more likely to become dependent, have frequent hospitalization readmissions, and may benefit from discussions about care wishes through ACP.101 Consideration of culture-related preferences was represented through five studies that were specifically culturally sensitive in their ACP approach, including 1) involvement from diverse backgrounds to help create advance directive documentation,80 2) consideration of influence of race/ethnicity in EOL care discussions,38 3) creation of a culturally appropriate ACP program in both English and Spanish,44 and 4) culturally sensitive ACP education.43 , 64 The influence of life values as a basis for ACP discussion and treatment preferences was explored in 11 studies. Studies reported that using life values as part of an advance directive may help to elucidate patients' desired medical care and guide physicians and proxies toward optimal representation of stated values.99 Six major personal life values included religiosity/spirituality,20 , 35 , 51 , 72 control,51 , 54 , 60 dignity,48 , 51 , 72 , 100 autonomy,51 , 72 comfort,72 , 79 , 100 and burden.79 , 100

Missed Communication

A sixth and final category centered on missed opportunities for ACP, reflected through themes of discomfort with discussion,20 , 54 , 58 , 65 , 75 , 86 absence or inadequacy of discussion,20 , 22 , 53 , 102 , 103 lack of documentation,37 , 102 and discordant documentation.65 , 98 , 102 An uncomfortable stage for ACP was discussed in six studies, describing patients' fears concerning death and dying,54 varying degrees of reticence, evasion, or reluctance to engage in conversations,86 the emotional burdens and responses associated with reflecting on death,20 , 58 and health-care providers' concern for causing maleficence to the patient.65 Caregiver discomfort with EOL topics was reflected in a desire to preserve normalcy.75 Five studies discussed the absence or inadequate nature of discussion, with two taking place in nursing homes, noting that very few nursing home patients and relatives had participated in conversations with nursing home staff about preferences and wishes regarding EOL care.53 , 103 The theme of discordant documentation was reported in three studies emphasizing incongruencies between written and verbal information that may lead to erroneous information entered into the electronic medical record. Discrepancies can lead to safety and quality concerns,98 and variance in documentation systems between care settings may hinder teamwork and jeopardize the medical safety of the patients if access of information is limited.65

Outcomes

Before 2018, the field of ACP research lacked a consensus about patient-centered outcome domains and constructs that defined successful ACP.104 The Delphi panel that created the consensus definition of ACP comprised a multidisciplinary panel of ACP experts to identify and rate patient-centered ACP outcomes that best define successful ACP.104 An Organizing Framework of ACP outcomes was created with four outcomes domains: 1) process, 2) action, 3) quality of care, and 4) health-care outcomes.104 Consistent with this framework, ACP outcomes in each of the reviewed studies were categorized under these domains ranging from process (e.g., increased comprehension of disease state) and action outcomes (e.g., completion of documents) to quality of care (e.g., family satisfaction) and health-care outcomes (e.g., decreased anxiety and depression). All the outcomes represent “uptake” or “absorbing and incorporating” ACP. A detailed description of ACP outcomes from our review is reported in Appendix II.

Discussion

From this integrative review, we determined the category of enhanced communication processes to be a vital necessity for successful ACP in older adults. While seemingly intuitive, this central category demonstrates that ACP does not occur without specific intention or conscious awareness on the part of health-care providers, organizations, and other stakeholders who recognize the need for ACP. This highlights opportunities for settings across the continuum to develop and integrate these processes based on available resources that are specific to the subpopulation of older adults at specific locations. For example, a faith community (church) of ethnically diverse older adults might integrate group discussions with a trained leader into regularly scheduled gatherings. Inversely, while enhanced communication may contribute to ACP, we also conclude that successful ACP reflects that an enhanced communication process has occurred.

This review reflects a broad and comprehensive appraisal of research that explored the uptake of ACP among older adults. Broadly, our findings portray optimal uptake of ACP as most likely to occur in older married adults with higher education and cognitive function, little to no mental health problems, strong social and family support, and who are able to receive structured enhanced communication approaches from prepared and qualified providers/clinicians. Regrettably, only a small segment of society fits this description or is fortuitous to receive the optimal approaches addressed in this review. In addition, subpopulations of older adults (minorities, economically disadvantaged) may respond differently to structured approaches. Our findings highlight opportunities for future research and clinical practice.

Future Research

Population aging and longer lifespans that lead to frailty and eventual EOL call for health-care systems that are proactive or that anticipate eventualities that will confront almost every person who reaches advanced age. The World Health Organization (WHO) stressed the need for a conceptual shift from reactive disease-based models to proactive health-based models that emphasize intrinsic capacity (composite of a person's physical and mental capacities) throughout the life course.105 Equipping older adults with increased understanding about intrinsic capacity related to aging that changes their awareness regarding the need to prepare and plan is an unexplored area for research. Such interventions might lead to improved uptake of ACP because individuals are better able to contemplate their aging, eventual decline and end of life, leading to a greater desire for control of their personal trajectory of aging and end of life. From this perspective, ACP might occur more upstream and in ways that normalize the process. Within health-care systems, innovative approaches are needed to proactively address the needs of prefrail and frail older adults and their families, including information needs and symptom management specific to age-related problems (e.g., loss of appetite, fatigue, pain, incontinence). Development of models of care that are patient-centered, holistic, and that recognize the unique legacy of older individuals is an area for innovation. Frailty-ready health-care systems are also needed to reduce older adult admissions requiring crisis care (e.g., falls) that lead to rapid decline and death.106

In contrast to the optimal scenario portrayed from our results, racially and economically disadvantaged older adults experience poorer health and more chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, shorter lifespans, and greater long-term care needs. Forty percent of older adults live at or near poverty levels, comprising a population that stands to benefit from cost-effective interventions that target disparities. Research has consistently reported low uptake of ACP among ethnic/racial minorities.107 , 108 Recent studies109 , 110 indicate that older ethnic/racial minorities are more likely to engage in ACP through informal dialogue than through the structured approaches presented in our review. Development of interventions that incorporate informal discussions about aging, frailty, and the need for ACP in natural settings (community centers, churches, assisted living) is an area for future research.

Clinical Practice

This integrative review holds implications for clinical practice by all members of the interdisciplinary health-care team. Recognition of the holistic elements that encompass ACP is the first step toward successful efforts to promote the uptake of ACP in older adults. For example, a clinician working in an outpatient setting may encounter an older patient with advanced frailty who may be more receptive to engage in ACP as they may be witnessing their body's transition. A clinician working in an inpatient setting about to conduct a family meeting in the intensive care unit may recognize the patient and family relationship patterns' affect decision-making related to the patient's personal values, goals, and preferences dealing with current critical illness. And a health-care worker in the skilled nursing facility may recognize the missed opportunity for communication with patients and families about care wishes, which resulted in an unnecessary transfer to the hospital given unknown care desires. It is also important to note that this integrative review specifically addresses ACP for older adults that may have chronic or serious illnesses along an aging trajectory. Specifically, ACP in older adults related to the acute pandemic of COVID-19 may require a different set of ACP skills and nuanced approaches.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this review is the broad and expansive nature that illuminates the older adults who are more likely to engage in ACP but also those who are less likely to engage via the structures and processes that traditionally facilitate ACP. Our conceptual model places “enhanced communication processes” as central to any ACP endeavor and calls for both public health and other care settings to be more proactive toward embedding approaches and processes that facilitate upstream planning for aging/frailty and ACP.

We also identified limitations within our review. The Joanna Briggs quality appraisal criteria recommend reporting of researchers' influence on the conducted research and vice versa. Few, if any of the studies that we reviewed reported such influence. Although old age is associated with accumulation of chronic conditions and multimorbidity, we did not include these terms in our search. Inclusion might have contributed to a richer understanding of ACP uptake related to aging. Several studies addressed the need for agreement about treatment preferences between patients and surrogates and patient-provider dyads. This may be reflected in the increased trust an older adult has in their family members and health-care providers carrying out their wishes. This is an area of future research highlighting age-group generational differences. Measurement of “care consistent with goals” is challenging as there is no standardized, valid, or reliable method to measure this outcome especially with a seriously ill population in which preferences may change over time.111 Finally, a major limitation revolves around the inconsistency of how ACP is depicted and explained in the research, as this was quite evident in the statistical and thematic reviews. Further recommendations involve using the ACP consensus definition as well as ACP outcome domains.

Conclusions

This integrative review advances understanding about the complexities involved in ACP uptake among older adults and provides a framework for evaluation of future efforts. ACP has evolved over the years to be more inclusive of the process involved rather than tasks of document completion. Future research in the field of ACP related to aging is needed across health-care disciplines, public domains (i.e., legal experts), governmental and policy officials, and the general public. Such efforts are essential to expanding the field and the underlying mission of advancing approaches to serious illness, aging, and frailty.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix I. Critical appraisal of studies

Appendix Table 1.

Critical Appraisal Qualitative Mixed Methods

| Author (Year) | Congruity Between the Stated Philosophical Perspective and the Research Methodology? | Congruity Between the Research Methodology and the Research Question or Objectives? | Congruity Between the Research Methodology and the Methods Used to Collect Data? | Congruity Between the Research Methodology and the Representation and Analysis of Data? | Congruity Between the Research Methodology and the Interpretation of Results? | Statement Locating the Researcher Culturally or Theoretically? | Is Influence of the Researcher on the Research, and Vice-Versa, Addressed? | Are Participants, and Their Voices, Adequately Represented? | Is the Research Ethical According to Current Criteria or, for Recent Studies? and Is There Evidence of Ethical Approval by an Appropriate Body? | Do the Conclusions Drawn in the Research Report Flow from the Analysis, or Interpretation, of the Data? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romo (2017)47 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Braun (2014)67 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Almack (2012)86 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Abdul-Razzak (2014)48 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Barnes (2007)60 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Gjerberg (2015)53 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Karasz (2010)68 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Malcomson (2009)50 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Seymour (2003)79 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UKN | UKN | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Piers (2013)54 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Pollak (2015)21 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Fried (2017)57 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| van Eechoud (2014)69 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Towsley (2015)103 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Cheang (2014)66 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | UKN | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Lum (2016)90 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Vandrevala (2002)51 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UKN | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Thoresen (2016)19 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Michael (2017)58 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UKN | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Simon (2015)20 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | UKN | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Peck (2018)49 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Taneja (2019)88 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Shaw (2018)56 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Schubart (2018)75 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Groebe (2019)59 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Kastbom (2019)65 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| Overbeek (2018)40 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y, Y | Y |

| De Vleminck (2018)22 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y |

Y = yes; N = no.

Appendix Table 2.

Critical Appraisal Randomized Controlled Trials

| Author (Year) | Was True Randomization Used for Assignment of Participants to Treatment Groups? | Was Allocation to Treatment Groups Concealed? | Were Treatment Groups Similar at the Baseline? | Were Participants Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were Those Delivering Treatment Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were Outcomes Assessors Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were Treatment Groups Treated Identically Other Than the Intervention of Interest? | Was Follow-up Complete? and if not, Were Differences Between Groups in Terms of Their Follow-up Adequately Described and Analyzed? | Were Participants Analyzed in the Groups to Which They Were Randomized? | Were Outcomes Measured in the Same Way for Treatment Groups? | Were Outcomes Measured in a Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | Was the Trial Design Appropriate, and any Deviations From the Standard RCT Design (Individual Randomization, Parallel Groups) Accounted for in the Conduct and Analysis of the Trial? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volandes (2009)25 | Y | Y | Y | UKN | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pearlman (2005)39 | N | N | Y | Y | N | UKN | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Detering (2010)57 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bravo (2016)62 | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tieu (2017)26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Periyakoil (2017)80 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Overbeek (2018)40 | Y | N | Y | UKN | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sudore (2018)44 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Paiva (2019)55 | UKN | UKN | N | UKN | UKN | UKN | Y | Y | UKN | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bose-Brill (2018)91 | N | N | Y | UKN | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bravo (2018)71 | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Lum (2018)96 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Y = yes; UKN = unknown; N = no.

Appendix Table 3.

Critical Appraisal Analytical Cross Sectional

| Author (Year) | Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | Were the Study Subjects and the Setting Described in Detail? | Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Were Objective, Standard Criteria Used for Measurement of the Condition? | Were Confounding Factors Identified? | Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brimblecombe (2014)81 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Chiu (2016)36 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Wu (2008)37 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Volandes (2016)41 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Silvester (2013)82 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Lankarani-Fard (2010)77 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| McCarthy (2008)29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ratner (2001)63 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Luck (2017)32 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Boerner (2013)30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Chu (2011)31 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hawkins (2005)72 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Chung (2017)34 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Winter (2013)100 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Heyland (2013)102 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Garrido (2013)35 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Schonwetter (1996)99 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tzeng (2019)95 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Nair (2019)42 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Dignam (2019)85 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hinderer (2019)64 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kim (2019)89 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Peterson (2019)38 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Cardona (2019)46 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Chu (2018)33 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Shaku (2019)76 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Zapata (2018)78 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sable-Smith (2018)24 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| DePriest (2019)84 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| David (2018)97 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Abdul-Razzak (2019)73 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hold (2019)83 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Mirarchi (2019)98 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Brungardt (2019)92 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hunter (2018)74 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Torke (2019)23 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Tan (2019)87 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Y = yes; N = no.

Appendix Table 4.

Critical Appraisal Quasi-Experimental (Nonrandomized Experimental Studies)

| Author (Year) | Is It Clear in the Study What Is the “Cause” and What Is the “Effect”? | Were the Participants Included in Any Comparisons Similar? | Were the Participants Included in Any Comparisons Receiving Similar Treatment/Care, Other than the Exposure or Intervention of Interest? | Was There a Control Group? | Were There Multiple Measurements of the Outcomes Both Before and After the Intervention/Exposure? | Was Follow-up Complete? And if Not, Were Differences Between Groups in Terms of Their Follow-up Adequately Described and Analyzed? | Were the Outcomes of Participants Included in Any Comparisons Measured in the Same Way? | Were Outcomes Measured in a Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan (2010)43 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y |

Y = yes.

Appendix II. Data Extraction Table for Uptake of Advance Care Planning (ACP) in Older Adults (78 Studies)

| References; Evidence Level | Study Objective | Setting and Location | Sample and Participant Characteristic | Design and Data Collection | ACP Uptake Feature or Factor | ACP Uptake Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romo (2017)47 Level 6 |

To explore how older adults in the community with a limited life expectancy make healthcare decisions and the processes used when they are not in an acute crisis | Outpatient; Medical programs and geriatrics clinics at the UCSF and San Francisco VAMC | n = 20; median 89, age range 67–98; male 65%, female 35% | Qualitative; semi-structured interviews conducted in participants' homes. | Interview guide developed to elicit participants' experience with decision-making and explore the underlying processes | Four themes emerged from the analysis that reflect the various approaches participants used to articulate their goals and maintain a sense of control: 1) direction communication, 2) third-party analogies, 3) adaptive denial, and 4) engaged avoidance. Importance of shared decision-making with provider-patient communication. Older adults allowed option of taking a more passive approach while still maintaining sense of control and personal autonomy |

| Luck (2017)32 Level 4 |

To examine the dissemination of advance directives (AD) specifically in the oldest-old individuals | Outpatient; General practice patients part of AgeQualiDe study; Participants recruited with six study centers in Germany | n = 704; Mean age 88.7 years; 472 (67.0%) women and 232 (33.0%) men. Not reported: age range, ethnicity | Quantitative; Observational, cross-sectional study. Home assessment | Interview: (i) frequency of ADs for health care, (ii) associated factors, (iii) groups of persons assisting in preparation of ADs, (iv) reasons for not having ADs in the very old, (v) information on frequency of POAs, (vi) associated factors, (vii) the groups of persons empowered. | Most frequently stated reason for not having ADs for health care was that the respondents trust their relatives or physicians to make right decisions for them when necessary (staged by 59.4% and 44.8% of those without ADs). Attitudinal reasons such as not wanting to concern themselves with the topic of ADs (28.1%) or have too many concerns regarding the usefulness of ADs (16.7%). When planning programs to offer ACP to oldest old, consider attitudinal differences of this target group, some simple trust their relatives/physicians in making the right decisions for them, and some may need more explanation and support for drawing up an advance care document |

| Brimblecombe (2014)81 Level 4 |

To review implementation of a Goals of Patient Care (GOPC) summary in medical inpatients and its applicability in emergency medical response (EMR) situations | Inpatient; general hospital in Mebourne, Australia | n = 101; mean age 72; age range 69–75; female n = 55; 36.6% non-English speaking; 71 patients admitted under general medicine. Targeted those likely to have issues of frailty and comorbidity that would impact treatment decisions. Not reported: ethnicity | Quantitative; Single center cross-sectional study | GOPC: presence and content. Secondary review of decision-making and discussion documentation, patient characteristics; EMR precipitants and outcomes | 80/82 patients with GOPC summary had life-prolonging treatment goals. Three months after introduction of the GOPC summary, formal consideration and documentation of overall aims occurred for 4/5 medical inpatients, with 85% of summaries completed within the first 48h of admission. Doctors may still have difficulties relating their medical judgement about prognosis and outcomes to a shared understanding of the individual's aims and do not consistently document discussion or details of decision-making |

| Chan (2010)43 Level 3 |

To develop an ACP program and determine its feasibility among Chinese frail nursing home residents. | Long term care; 4 residential nursing care homes in Hong Kong | n = 121; mean age 83.5 years, age range 66–100; female 69% | Quantitative; quasi-experimental with an intervention and comparison group; 1-year study. Each participating nursing home had one intervention and one comparison group. Participants divided according to the story their lived on. | Let me talk ACP program designed to encourage participants to talk about their deepest concerns with a nurse facilitator guiding the participants to share their stories and express their end-of-life care wishes. A personal booklet summarizing participants' life stories and views and documenting their health care concerns, life-sustaining treatment preferences and preferred decision-maker was prepared for each participant by end of program. After completion of program, participant's family members were invited to a family conference for addressing the participant's concerns and end-of-life care preferences. The facilitator acted as a mediator to facilitate communication between the participant and family or caregivers | Participants in intervention group were able to indicate their treatment preferences. Many nursing home residents were prepared to discussion death and dying issues that are considered taboo topics in Chinese culture. Program effective in enhancing the preference stability in the intervention group. One possible explanation is that the story-telling approach encouraged the participants to review past experiences and thus explore their deeply held personal values and beliefs which enabled them to ascertain their life goals and clarify their preferences. The mitigation of existential distress noted in this study may partly relate to the life storytelling process, which allowed older people to visualize their life as a whole and once again be conscious of its meaning. |

| Volandes (2009)25 Level 2 |

To compare the concordance of preferences among elderly patients and their surrogates listening to only a verbal description of advanced dementia or viewing a video decision support tool of the disease after hearing the verbal description | Outpatient; Community dwelling elderly and their surrogates conducted at 2 geriatric clinics affiliated with 2 academic medical centers in Boston | n = 14 pairs of patients and their surrogates; n = 6 verbal narrative, n = 8 video after verbal narrative. Elderly persons n = 14, mean age 83, female 50%, white n = 14. Surrogates n = 14, mean age 67.5, female 79%, White n = 14 | Quantitative; RCT; all patient-surrogate dyads randomized into 1 of 2 decision-making modalities: control group (listening to verbal narrative describing advanced dementia) or intervention group (listening to a verbal narrative followed by viewing a 2-minute video decision-support tool depicting a patient with advanced dementia). | Video depicts a person with advanced dementia together with her 2 daughters in the nursing home setting. The patient fails to respond attempts at conversation, is pushed in a wheelchair, and is hand-fed pureed food, all depicting someone with FAST 7a dementia | Patients and surrogates viewing video decision-support tool for advanced dementia are more likely to concur about the patient's end-of-life preferences than when listening to a verbal description of the disease. Viewing the video decision-support tool was associated with a trend toward more knowledge of advanced dementia among both patients and their surrogates |

| Boerner (2013)30 Level 4 |

To evaluate the effects of three aspects of family relations- general family functioning, support and criticism from spouse, and support and criticism from children- on both overall ACP and specific durable power of attorney for health care (DPAHC) | Outpatient; two large university hospitals and one comprehensive cancer center in New Jersey. Participants from the New Jersey End-of-Life study of noninstitutionalized adults aged 55 years and older | n = 293; average age 69: female ∼67%. Not reported: ethnicity | Quantitative; cross-sectional study; 1.5 hours face to face interview using computer-assisted personal interview technology | Consideration of family dynamics affect on ACP through categories of a two-pronged approach (AD and discussions), discussions only, and no planning (omitted category) | In general, families who are best equipped to make collaborative decisions about end-of-life care and to weather the distress associated with bereavement are precisely the persons who engage in ACP in the first place, those with high levels of family functioning. Person with low levels of family functioning including problematic decision making and communication styles are least likely to engage in ACP |

| Heyland (2013)102 Level 4 |

To inquire about patients' ACP activities before hospitalization and preferences for care from the perspectives of patients and family members, as well as to measure real-time concordance between expressed preferences for care and documentation of those preferences in the medical record | Inpatient; 12 acute care hospitals in Canada | n = 278 patients, mean age 80, female 53%, white n = 263; n = 225 family members, mean age mean age 60.8 years, female 61%, white n = 221 | Quantitative; Multicenter, prospective study; separate face-to-face interviews with patients and family members | Assessment of ACP activities and preferences through a questionnaire and then concordance of expressed preferences and orders of care documented in the medical record. Questions related to domains relevant to communication and decision making (relationship with physicians, communication, decision making, and role of family) | The majority of patients and family members had considered and discussed the use or nonuse of life-sustaining technologies near the EOL and could clearly express their preferences for EOL care. There was little effective communication about ACP between the patient or family and members of the health care team before hospitalization. Less than one-third of patients and families reported that they had been asked about their advance care plans on admission to the hospital |

| Pearlman (2005)39 Level 2 |

To evaluate the effectiveness of a comprehensive, systems-oriented ACP intervention that included the Your Life, Your Choices workbook | Outpatient; Department of Veteran Affairs outpatient clinics | Intervention group n = 119, mean age 68.5, male 95%; White 89%, African American 8%, Other 3%; Control group n = 129, mean age 69.5, male 95%, White 88%, African American 9%, Other 3%; Primary care providers recruited and then patients from their practices recruited | Quantitative; Block-RCT with multifaceted ACP intervention. Two days after index visit, patients in both groups were called whether they had discussed ACP with their providers. All other outcomes data collected 4 months after the index visit to allow sufficient time for the ACP process and follow-up visits to occur | ACP workbook, Your Life, Your Choices, a 52-page workbook that incorporates concepts from multiple frameworks including stages of behavioral change, the health belief model, self-efficacy, the relationship between states/fates worse than death and patient preferences to forego life-sustaining treatment, and general guidelines about human information processing and information design. Workbook has three parts: 1) case stories written to convey basic information and motivate persons to engage in ACP behaviors; 2) 4 subsections including exercises to elicit values about quality of life, glossary describing health states that may cause decisional incapacity, life-sustaining treatments, and palliative care, documents for recording health state ratings and treatment preferences, and advice about communicating with family members and health care providers; 3) advice about communicating with family members and health care providers. Intervention group received workbook, 30-minute appointment with Social Worker before provider visit. Control group mailed 8-page advance directive packet which included the living will and durable power of attorney for health care forms prior to scheduled appointment. | The intervention was successful in increasing ACP discussion, all aspects of directive completion, and filing of advance directives in the medical record. Rate of documentation doubled, though achieved 48%, and may represent ceiling effect if advance directives are not for everyone. The intervention had no effect on agreement between proxies and patients for any of the treatments of quality-of-life assessments. |

| Chiu (2016)36 Level 4 |

To determine the decision control preferences (DCPs) of diverse, older adults and whether DCPs are associated with participant characteristics, ACP, and communication satisfaction | Mixed; hospital, Veteran Affairs medical center, low-income senior centers, cancer support groups all in San Francisco | n = 146; mean age 70.8; female 41%, White n = 69, African American n = 39, Latino or Hispanic n = 10, Asian or Pacific Islander n = 19, Multiethnic n = 9 | Quantitative; Cross-sectional survey data pooled from four cohort studies | Use of DCPs to assess the degree of control patients prefer medical decisions made with their doctors. Doctor makes all decisions (low), shares with doctor (medium), makes own decisions (high) | 18% wanted doctors to make all of their medical decisions (low DCPS). 34% wanted to share medical decisions (moderate DCPs). 48% wanted to make their own medical decisions. Almost one-fifth of diverse, community dwelling older adults with multiple comorbidities wanted their doctors to make medical decisions for them. Older age was the only patient characteristic significantly associated with lower DCPs. |

| Wu (2008)37 Level 4 |

To describe end-of-life ACP among the oldest-old and to identify patient characteristics and healthcare utilization patterns associated with likelihood of care planning documentation | Mixed, chart review; Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VA GLAHS) | n = 175; median 88 years old, age range (85–104), Male n = 174, White n = 133, African American n = 24, Hispanic n = 8, other n = 1 | Quantitative; retrospective chart review | Examination of care preference documentation using electronic medical records | Care preference documentation and surrogate identification occurred for 50/149 (34%). Thirty (60%) care preferences were first documented during an inpatient episode. Seventy-nine (53%) had no preference documentation, including 14 (9%) provider attempts to elicit discussion. Sixty-eight (46%) of 149 charts documented a surrogate for health care decisions. Eighty-one (54%) patients had no identified surrogate, including 9 (6%) with attempted discussions. Outpatient utilization had the largest impact on documentation, dictated mostly by general and geriatric visits |

| Chu (2011)31 Level 4 |

To describe the knowledge and preferences of Hong Kong Chinese older adults regarding advance directive and end-of-life care decisions, and to investigate the predictors of preferences for advance directive and community end-of-life care in nursing homes | Long-term care; 140 nursing homes in Hong Kong | n = 1600; mean age 82.37; female n = 1060; | Quantitative; cross-sectional survey; face-to-face interviews | Interview with discussion of advance directives, hypothetical conditions (cancer and noncancer terminal conditions), life-sustaining treatments or devices, and location of care settings in end-of-life. | 94.2% Participants would prefer to be informed of the diagnosis if they had a terminal disease. 77.3% would prefer to stay in their present nursing home until the last days of life. 96% participants had not heard of the term advance directive previously. After explanation of the meaning of advance directive, 88% agreed that it would be good to have an advance directive for them regarding medical treatment decisions in the future. 90% participants would prefer to know the diagnosis of a terminal disease. The strongest predictor for having an advance directive was the wish to be informed of a terminal illness |

| Volandes (2016)41 Level 4 |

To examine with ACP documentation would increase after ACP video implementation. To evaluation use of hospice, hospital mortality, and cost associated in the last month of life | Mixed; Community; Hilo, Hawaii which is serviced by one 276 bed hospital, one hospice, and 30 primary care practices | City of Hilo in Hawaii (population 43,263); Population of diverse backgrounds: Asian 34%, 2 or more races 33%, White 18%, Native Hawai'ian and Pacific Islander 14%, Latino 10%; Inpatient: Control: n = 346, mean age 67, Female 45%; Video intervention: n = 2773, mean age 70.2, Female n = 1292. Outpatient: All PCPs not in Hilo: n = 42,099, mean age 84.1, Female = 25,680; All PCPs in Hilo: n = 3888, mean age 84.0, Female n = 2294 | Quantitative; Implementation study x 21 months | ACP video decision aid. Videos attempt to provide a general framework to which to understand ACP including the broad questions that patients should reflect upon and how individual preferences can be translated into actionable medical orders and interventions | After intervention, there was an increase in ACP documentation of patients' preferences in the inpatient and outpatient settings. More patients with advanced illness were likely to be discharged to hospice, which was reflected in decreased hospital death rates. In the year after the implementation of videos, the hospice admission rate grew in Hilo (28%) relative to the rest of the state (12%) and national trends (4%) and decreased costs in the last month of life for decedents. Recommendations: decisions aids can play an important role in prompting discussions with providers who may not feel that they were adequately trained to have these discussions otherwise |

| Braun (2014)67 Level 6 |

To describe self-reported decision-making styles and associated pathways through end-of-life (EOL) decision-making for African-American, Caucasian, and Hispanic seriously ill male Veterans, and to examine potential relationships of race/ethnicity on these styles | Community; VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas | n = 44 participated in one of eight focus groups; mean age 57.8, age range 55–83, female n = 1, African American n = 14, Hispanic n = 17, Caucasian n = 13 | Qualitative; Focus groups lasting 5–90 minutes. Focus groups organized by race/ethnicity with female, trained, race/ethnicity concordant moderators with experience in qualitative research | Focus groups to determine patients' selection of their preferred decision-making style as the first step in EOL decision making. | Two fundamental decision-making styles emerged: deciding for oneself or allowing others to decide, with five important variants in how patients expressed and justified these styles. Deciding for oneself: “Autonomists” (takes responsibility for one's decisions) and “Altruists” (does not want to burden others with decision making). Letting others decide: “Authorizers” (transfers authority by explicit authorization), “Absolute Truster” (transfers authority by implicit authorization), and “Avoider” (accepts surrogates' decision making by default). No apparent relation to race/ethnicity in terms of the two basic decision-making styles or the five variants. |

| Almack (2012)86 Level 6 |

To explore with patients, carers, and health care professionals if, when and how advance care planning conversations about patients' preferences for place of care (and death) were facilitated and documented | Mixed; five care services with involvement in palliative care were selected across one region (urban and rural England), chosen to cover palliative care provision for cancer and noncancer populations | n = 18 cases (18 patients; 11 relatives) initial interview, female = 8; mean age 73; n = 6 cases (5 patients; 5 relatives) follow-up interview | Qualitative; exploratory case study design; retrospective audit of care delivered in the last four weeks of life and then followed by interviews | Explore perspectives of all parties concerned (healthcare professionals, patients and family carers). Use Preferred Place of Care (PPC) tool. Discussion and recording of these preferences of patients on place of care and death were felt as important means of supporting and enabling patient choice. | Patients demonstrated varying degrees of reticence, evasion, or reluctance to initiate any conversations about end-of-life care preferences. Most assumed staff would initiate conversations and often staff were hesitant to do so. Staff identified barriers including the perceived risks of taking away hope and issues of timing. Staff were often guided by cues from the patient or by intuition about when to initiate these discussions |

| Abdul-Razzak (2014)48 Level 6 |

To understand patients' preferences for physician behaviors during end-of-life communication | Inpatient; 3 Canadian academic tertiary hospitals | n = 16; Female 69%, age: 55–59 (n = 1), age 60–69 (n = 4), age 70–79 (n = 2), age 80–89 (n = 6), age >89 (n = 3); Caucasian n = 12, non-Caucasian n = 0; 70% noncancer diagnosis | Qualitative; Interpretative descriptive method from semi-structured interviews conducted with patients admitted to general medical wards. Interviews ranged from 22 to 78 minutes in duration | Interview guide with qualitative approach to understand patient perspectives on physician behaviors to incorporate into physician's clinical practice and gain information for communication skills training initiatives for physicians and trainees | Two major themes: 1) “knowing me” relates to the influence of life history and social relationships on shaping personal values and preferences for health care; theme subdivided into subthemes of acknowledging family roles and respecting one's background; 2) ‘conditional candour’ describes a preference for receiving frank information from a physician, but with some important qualifications, which are elaborated in subthemes of assessing readiness, being invited to the conversation, and appropriate delivery of information |

| Schonwetter (1996)99 Level 4 |

To determine whether life values are related to resuscitation preferences and living will completion in an older population and to assess beliefs about the applicability of living wills | Community: independent retirement community | n = 132; mean age 79.3; well-educated, informed older population that may have obtained knowledge of subject matter at social service department of the retirement community; Not reported: gender, ethnicity | Quantitative; structured, individual interviews | Questionnaire with knowledge assessment, preference of care in hypothetical clinical scenarios, and completion of 13 life value statements in terms of their importance for their medical decision-making near the end-of-life | Results suggest discussions concerning advance directives should include an evaluation of the patient's value system and that patients should be better educated concerning the applicability of their advance directive documents. Using life values as part of an advance directive may not only allow patients to better understand the type of medical care they want in the future but also guide physicians and proxies by the patient's stated values |

| Barnes (2007)60 Level 6 |

To explore the acceptability of an interview schedule designed to encourage conversations regarding future care and to explore the suitability of such discussions and inquire about their possible timing, nature and impact | Mixed; outpatient, hospice, day unit; Focus group occurred at academic department of university setting; United Kingdom | n = 22; age range 32–80, median age 60; female 59%, Caucasian n = 21 | Qualitative; Focus groups, 8 total, each lasting about 1 hour, no more than 4 participants in each group; Participants considered the ACP interview schedule for one week and then attended a focus group | ACP interview schedule inquired about experiences of care, clinical and personal circumstances, worries and concerns regarding the future, and whether the patient might wish to complete a written advance directive. Focus groups used to explore wider acceptability of the interview schedule, suitability of discussions and timing, nature and impact. | Emergent themes include: prompting patients to think about issues, timing of ACP, recognizing individuality, person conducting ACP discussion, losing a sense of hope, maintaining a sense of control, advance directives, and effect of taking part in a focus group. |

| Garrido (2013)35 Level 4 |