Abstract

In reversible computing, the management of space is subject to two broad classes of constraints. First, as with general-purpose computation, every allocation must be paired with a matching de-allocation. Second, space can only be safely de-allocated if its contents are restored to their initial value from allocation time. Generally speaking, the state of the art provides limited partial solutions, either leaving both constraints to programmers’ assertions or imposing a stack discipline to address the first constraint and leaving the second constraint to programmers’ assertions.

We propose a novel approach based on the idea of fractional types. As a simple intuitive example, allocation of a new boolean value initialized to

also creates a value

also creates a value  that can be thought of as a garbage collection (GC) process specialized to reclaim, and only reclaim, storage containing the value

that can be thought of as a garbage collection (GC) process specialized to reclaim, and only reclaim, storage containing the value  . This GC process is a first-class entity that can be manipulated, decomposed into smaller processes and combined with other GC processes.

. This GC process is a first-class entity that can be manipulated, decomposed into smaller processes and combined with other GC processes.

We formalize this idea in the context of a reversible language founded on type isomorphisms, prove its fundamental correctness properties, and illustrate its expressiveness using a wide variety of examples. The development is backed by a fully-formalized Agda implementation (https://github.com/DreamLinuxer/FracAncilla).

Keywords: Reversible computing, Monoidal categories, Type isomorphisms, Pointed types, Program extraction, Agda

Introduction

We solve the ancilla problem in reversible computation using a novel concept: fractional types. In the next section, we introduce the problem of ancilla management, motivate its importance, and explain the limitations of current approaches.

Although the concept of fractional types could potentially be integrated with general-purpose languages, its natural technical definition exploits symmetries present in the categorical model of type isomorphisms. To that end, we first review in Sect. 3 our previous work [7, 8, 13, 14] on a reversible programming language built using type isomorphisms. In Sect. 4, we introduce a simple version of fractional types that allows allocation and de-allocation of ancilla bits in patterns beyond the scoped model but, like existing stack-based solutions, still requires a runtime check to verify the safety of de-allocation. In Sect. 5 we show how to remove this runtime check, by lifting programs to a richer type system with pointed types, expressing the proofs of safety in that setting, and then, from the proofs, extracting programs with guaranteed safe de-allocations and no runtime checks. The last section concludes with a summary of our results.

Ancilla Bits: Review and a Type-Based Approach

Restricting a reversible circuit to use no ancilla bits is like restricting a Turing machine to use no memory other than the n bits used to represent the input [1]. Since such a restriction disallows countless computations for trivial reasons, reversible models of computation have, since their inception, included management for scratch storage in the form of ancilla bits [25] with the fundamental restriction that such bits must be returned to their initial states before being safely reused or de-allocated.

Review

Reversible programming languages adopt different approaches to the management of ancilla bits, which we review below.

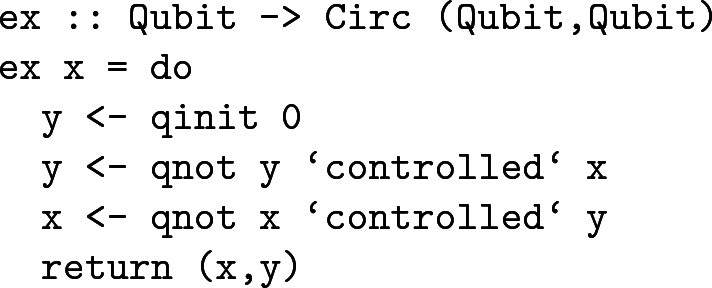

Quipper [12]. The language provides a scoped mechanism to manage ancilla bits via: ![]() The operator takes a block of gates parameterized by an ancilla value, allocates a new ancilla value of type Qubit initialized to

The operator takes a block of gates parameterized by an ancilla value, allocates a new ancilla value of type Qubit initialized to  , and runs the given block of gates. At the end of its execution, the block is expected to return the ancilla value to the state

, and runs the given block of gates. At the end of its execution, the block is expected to return the ancilla value to the state  at which point it is de-allocated. The expectation that the ancilla value is in the state

at which point it is de-allocated. The expectation that the ancilla value is in the state  is enforced via a runtime check.

is enforced via a runtime check.

Quipper also provides primitives qinit and qterm, which allow programmers to manage ancilla bits manually without scoping constraints. This management is not supported by the type system, however. For example, the following statically-valid expression allocates an ancilla bit using qinit but neither it nor its caller are required by the type system to de-allocate it:

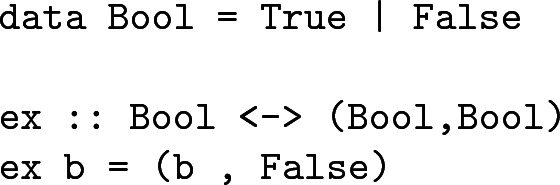

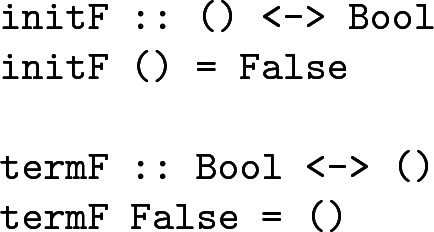

rFun [23, 26]. This language similarly allows expressions to freely allocate constant values:

Using such expressions, it is possible to define expressions that behave like qinit and qterm in Quipper:

At run-time termF might fail with an incomplete pattern-matching exception but, statically, the type system neither enforces that termF is called nor that it is called with only the value False.

Ricercar [24]. This language uses a scoped way to manage ancilla bits. The expression  allocates an ancilla wire x for the gate A requiring that x is set to 0 after the evaluation of A.

allocates an ancilla wire x for the gate A requiring that x is set to 0 after the evaluation of A.

Janus [27]. This is a reversible imperative programming language that is not based on the circuit model but as Rose [20] explains, its treatment is essentially similar to above:

All variables in original Janus are global, but in the University of Copenhagen interpreter you can allocate local variables with the local statement. The inverse of the local statement is the delocal statement, which performs deallocation. When inverted, the deallocation becomes the allocation and vice versa. In order to invert deallocation, the value of the variable at deallocation time must be known, so the syntax is delocal<variable> =<value>. Again the onus is on the programmer to ensure that the equality actually holds.

A Type-Based Approach

The approaches above are pragmatic but limited in two ways: non-scoped approaches do not enforce de-allocation and scoped ones do not enforce that the de-allocated bit has the correct value. To understand these points more vividly, consider the following analogy: allocating an ancilla bit by creating a new wire in the circuit is like borrowing some money from a global external entity (the memory manager); the computation has access to a new resource temporarily. De-allocating the ancilla bit is like returning the borrowed money to the global entity; the computation no longer has access to that resource. It would however be unreasonably restrictive to insist that the person (function) borrowing the money must be the same person (function) returning it. Indeed, as far as reversible computation is concerned, the only important invariant is that information is conserved, i.e., that money is conserved. The identities of bits are not observable as they are all interchangeable in the same way that particular bills with different serial numbers are interchangeable in financial transactions. Thus the only invariant is that the net flow of money between the computation and the global entity is zero. This observation allows us to go even further than just switching the identities of borrowers. It is even possible for one person to borrow $10, and have three different persons collectively collaborate to pay back the debt with one person paying $5, another $2, and a third $3, or the opposite situation of gradually borrowing $10 and returning it all at once.

Computationally, this extra generality is not a gratuitous concern: since scope is a static property of programs, it does not allow the flexibility of heap allocation in which the lifetime of resources is dynamically determined. Furthermore, limiting ancilla bits to static scope does not help in solving the fundamental problem of ensuring that their value is properly restored to their initial value before de-allocation.

We demonstrate that both problems can be solved with a typing discipline. The main idea is simple: we introduce a type representing “processes specialized to garbage-collect specific values.” The infrastructure of reversible computing will ensure that the information inherent in this process will never be duplicated or erased, enforcing that proper, safe, de-allocation must happen in a complete program. Furthermore, since reversible computation focuses on conservation of information rather than syntactic entities, this approach will permit fascinating mechanisms in which allocations and de-allocations can be sliced and diced, decomposed and recomposed, run forwards and backwards, in arbitrary ways as long as the net balance is 0.

Preliminaries:

The syntax of the language  [8] consists of several sorts:

[8] consists of several sorts:

|

Focusing on finite types, the building blocks of the type theory are: the empty type (0), the unit type (1, where  is the only inhabitant), the sum type (

is the only inhabitant), the sum type ( ), and the product (

), and the product ( ) type. One may view each type

) type. One may view each type  as a collection of physical wires that can transmit

as a collection of physical wires that can transmit  distinct values where

distinct values where  is a natural number that indicates the size of a type, computed as:

is a natural number that indicates the size of a type, computed as:  ;

;  ;

;  ; and

; and  . Thus the type

. Thus the type  corresponds to a wire that can transmit one of two values, i.e., bits, with the convention that

corresponds to a wire that can transmit one of two values, i.e., bits, with the convention that  represents

represents

and

and  represents

represents

. The type

. The type  corresponds to a collection of wires that can transmit three bits. From that perspective, a type isomorphism between types

corresponds to a collection of wires that can transmit three bits. From that perspective, a type isomorphism between types  and

and  (such that

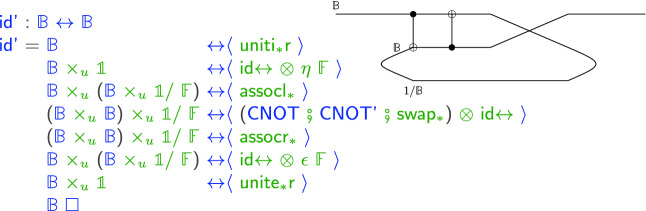

(such that  ) models a reversible combinational circuit that permutes the n different values. These type isomorphisms are collected in Fig. 1. It is known that these type isomorphisms are sound and complete for all permutations on finite types [9, 10] and hence that they are complete for expressing combinational circuits [11, 13, 25]. Algebraically, these types and combinators form a commutative semiring (up to type isomorphism). Logically they form a superstructural logic capturing space-time tradeoffs [21]. Categorically, they form a distributive bimonoidal category [17].

) models a reversible combinational circuit that permutes the n different values. These type isomorphisms are collected in Fig. 1. It is known that these type isomorphisms are sound and complete for all permutations on finite types [9, 10] and hence that they are complete for expressing combinational circuits [11, 13, 25]. Algebraically, these types and combinators form a commutative semiring (up to type isomorphism). Logically they form a superstructural logic capturing space-time tradeoffs [21]. Categorically, they form a distributive bimonoidal category [17].

Fig. 1.

-terms and combinators.

-terms and combinators.

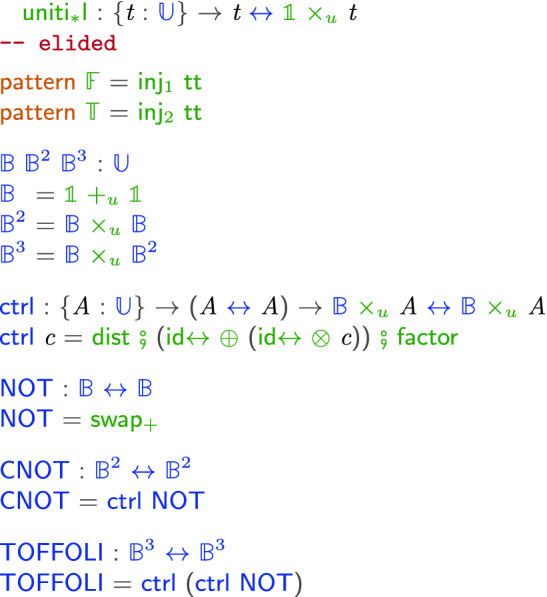

Below, we show code, in our Agda formalization, that defines types corresponding to bits (booleans), two-bits, and three-bits. We then define an operator  that builds a controlled version of a given combinator c. This controlled version takes an additional “control” bit and only applies c if the control bit is true. The code then iterates the control operation several times starting from boolean negation building up to Toffoli.

that builds a controlled version of a given combinator c. This controlled version takes an additional “control” bit and only applies c if the control bit is true. The code then iterates the control operation several times starting from boolean negation building up to Toffoli.

Although austere, this combinator-based language has the advantage of being more amenable to formal analysis for at least two reasons: (i) it is conceptually simple and small, and (ii) it has direct and evident connections to type theory and category theory. Indeed our solution for managing ancillae is inspired by the construction of compact closed categories [2, 3, 15]. These categories extend the monoidal categories [4, 5, 18] which are used to model many resource-aware (e.g., based on linear types) programming languages [6, 16] (including  ) with a new type constructor that creates duals or inverses to existing types. This dual will be our fractional type.

) with a new type constructor that creates duals or inverses to existing types. This dual will be our fractional type.

First-Class Garbage Collectors

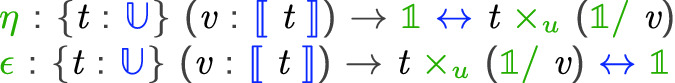

The main idea is to extend the  terms with two combinators

terms with two combinators  and

and  witnessing the isomorphism

witnessing the isomorphism  . The names and types of these operations are inspired by compact closed categories which are extensions of the monoidal categories that model

. The names and types of these operations are inspired by compact closed categories which are extensions of the monoidal categories that model  . Intuitively,

. Intuitively,  allows one, from “no information,” to create a pair of a value of type A and a value of type

allows one, from “no information,” to create a pair of a value of type A and a value of type  . We interpret the latter value as a GC process specialized to collect the created value. Dually,

. We interpret the latter value as a GC process specialized to collect the created value. Dually,  applies the GC process to the appropriate value annihilating both.1

applies the GC process to the appropriate value annihilating both.1

To make this idea work, several technical issues need to be dealt with. Most notably, we must exclude the empty type from this creation and annihilation process. Otherwise, we would be able to prove that:

|

The second important issue is to ensure that the GC process is specialized to collect a particular value. We therefore exploit ideas from dependent type theory to treat individual values as singleton types. More precisely, we extend the syntax of core  in Sect. 3 as follows:

in Sect. 3 as follows:

|

For now, the core  language is simply extended with a new type

language is simply extended with a new type  which represents a GC process specialized to collect the value v. Since all relevant information is present in the type, at runtime, this GC process is represented using a trivial value denoted by

which represents a GC process specialized to collect the value v. Since all relevant information is present in the type, at runtime, this GC process is represented using a trivial value denoted by  . The combinators

. The combinators  and

and  are parameterized by the value v (and its type

are parameterized by the value v (and its type  ) which serves two purposes. First it guarantees that the combinators operate on non-empty types, and second it fixes the type of the GC process. At this point, however, although the language guarantees that the GC process can only collect a particular value, the type system does not track the value created by

) which serves two purposes. First it guarantees that the combinators operate on non-empty types, and second it fixes the type of the GC process. At this point, however, although the language guarantees that the GC process can only collect a particular value, the type system does not track the value created by  , nor does it predict the value that reaches

, nor does it predict the value that reaches  . In other words, it is possible to write programs in which

. In other words, it is possible to write programs in which  expects one value but is instead applied to another value. In this section, we will deal with such situations by including a runtime check in the formal semantics, and show how to remove it, via a safety proof, in the next section.

expects one value but is instead applied to another value. In this section, we will deal with such situations by including a runtime check in the formal semantics, and show how to remove it, via a safety proof, in the next section.

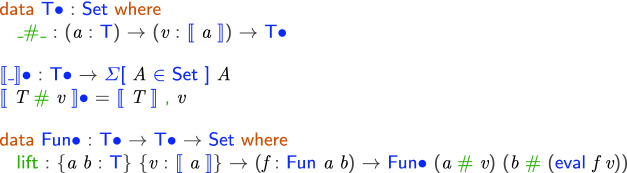

Our Agda formalization clarifies our semantics, with the new type as:![]()

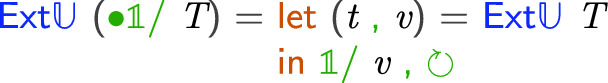

The new combinators are defined as follows:

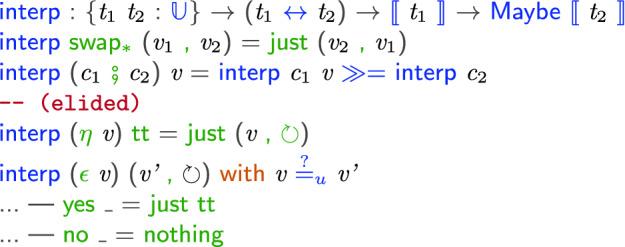

The most relevant excerpt of the formal semantics is given below:

The interpreter either returns a proper value  or throws an exception

or throws an exception

. The semantics of the core

. The semantics of the core  combinators performs the appropriate isomorphism and returns a proper value. At

combinators performs the appropriate isomorphism and returns a proper value. At  , the v that parameterizes the combinator is used to create a new value v and a GC process specialized to collect it. By the time evaluation reaches

, the v that parameterizes the combinator is used to create a new value v and a GC process specialized to collect it. By the time evaluation reaches  , the value created by

, the value created by  may have undergone arbitrary transformations and is not guaranteed to be the value expected by the GC process. A runtime check is performed: if the value is the expected one, it is annihilated together with the GC process; otherwise an exception is thrown which is demonstrated in the following example which returns normally if given

may have undergone arbitrary transformations and is not guaranteed to be the value expected by the GC process. A runtime check is performed: if the value is the expected one, it is annihilated together with the GC process; otherwise an exception is thrown which is demonstrated in the following example which returns normally if given

and otherwise throws an exception:

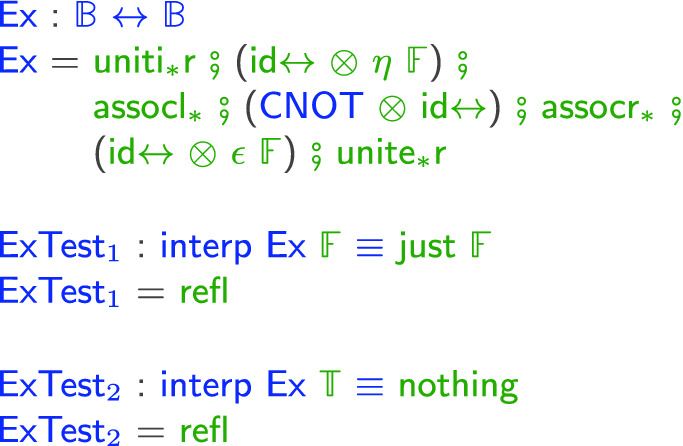

and otherwise throws an exception:

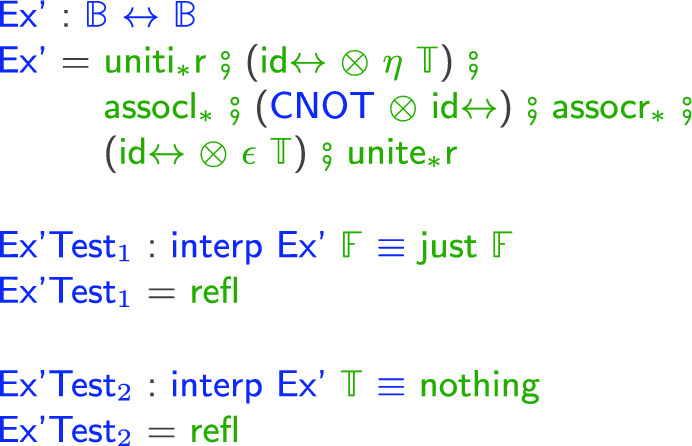

Changing the value used to instantiate  will force a corresponding change for

will force a corresponding change for  :

:

For future reference, we will call this language  for the fractional extension of

for the fractional extension of  with a dynamic check. We illustrate the expressiveness of the language with two small examples. The Agda code for the examples is written in a style that reveals the intermediate steps for expository purposes.

with a dynamic check. We illustrate the expressiveness of the language with two small examples. The Agda code for the examples is written in a style that reveals the intermediate steps for expository purposes.

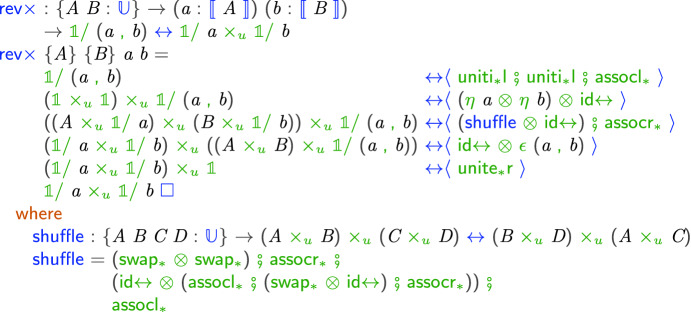

The first circuit has one input and one output. Immediately after receiving the input, the circuit generates an ancilla wire and its corresponding GC process (first two steps in the Agda definition). The original input and the ancilla wire interact using two

gates, after which the ancilla wire is redirected to the output (next three steps in the Agda code). Finally the original input is GC’ed (last two steps in the Agda code). The entire circuit is extensionally equivalent to the identity function but it does highlight an important functionality beyond scoped ancilla management: the allocated ancilla bit is redirected to the output and a completely different bit (with the proper default value) is collected instead.

gates, after which the ancilla wire is redirected to the output (next three steps in the Agda code). Finally the original input is GC’ed (last two steps in the Agda code). The entire circuit is extensionally equivalent to the identity function but it does highlight an important functionality beyond scoped ancilla management: the allocated ancilla bit is redirected to the output and a completely different bit (with the proper default value) is collected instead.

The second example illustrates the manipulation of GC processes. A process for collecting a pair of values can be decomposed into two processes each collecting one of the values (and vice-versa):

Dependently-Typed Garbage Collectors

By lifting the scoping restriction, the development in the previous sections is already more general than the state of the art in ancilla management. It still shares the same limitation of needing a runtime check to ensure ancilla values are properly restored to their allocation value [12, 24]. We now address this limitation using a combination of pointed types, singleton types, monads, and comonads.

Lifting Evaluation to the Type System

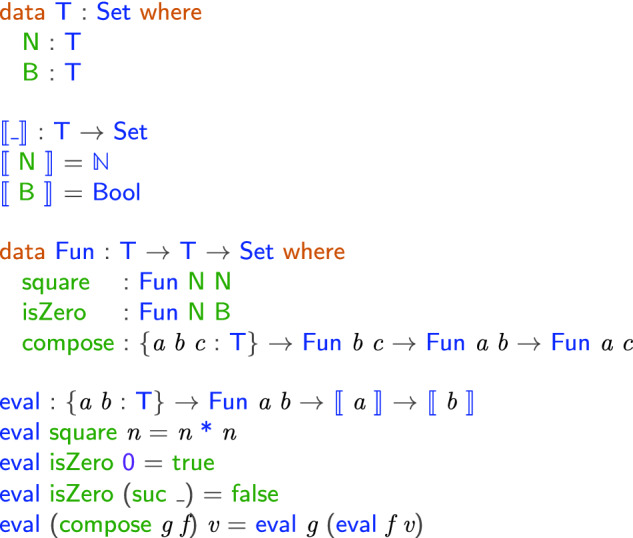

Before giving all the (rather involved) technical details, we highlight the main idea using the toy language below:

The toy language has two types (natural numbers and booleans) and two functions

and

and

and their compositions. Say we wanted to prove that

and their compositions. Say we wanted to prove that

always returns

always returns

when applied to a non-zero natural number. We can certainly do this proof in Agda (i.e., in the meta-language of our formalization) but we would like to do the proof within the toy language itself. The most important reason is that it can then be used within the language to optimize programs (or, for the case of

when applied to a non-zero natural number. We can certainly do this proof in Agda (i.e., in the meta-language of our formalization) but we would like to do the proof within the toy language itself. The most important reason is that it can then be used within the language to optimize programs (or, for the case of  , to remove a runtime check).

, to remove a runtime check).

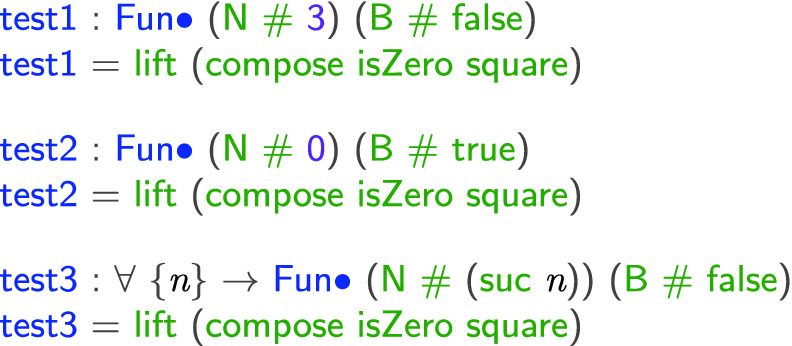

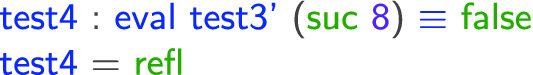

The strategy we adopt is to create a lifted version of the toy language with pointed types [22], i.e., types paired with a value of the type. In the lifted language, the evaluation function has an interesting type: it keeps track of the result of evaluation within the type:

This allows various properties of

to be derived within the extended type system. For example:

to be derived within the extended type system. For example:

The first two tests show that the type system can track exact concrete values. More interestingly,

shows a property that holds for all natural numbers n; its proof uses “symbolic” evaluation within the type system. In more detail, from the definition of

shows a property that holds for all natural numbers n; its proof uses “symbolic” evaluation within the type system. In more detail, from the definition of

, we see that

, we see that

produces

produces

; by definition of multiplication, this is an expression with a leading

; by definition of multiplication, this is an expression with a leading

constructor which is enough to determine that evaluating

constructor which is enough to determine that evaluating

on it yields

on it yields

. This form of partial evaluation is quite expressive, and sufficient to allow to keep track of ancilla values throughout complex programs.

. This form of partial evaluation is quite expressive, and sufficient to allow to keep track of ancilla values throughout complex programs.

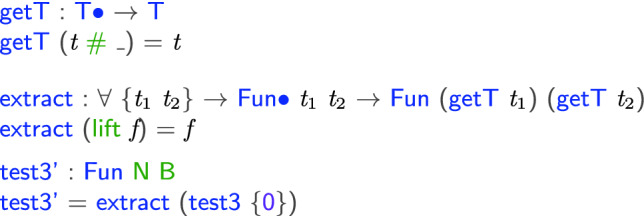

After proving properties about a program in

, we can extract a

, we can extract a

program that still satisfies those properties.

program that still satisfies those properties.

Note that, since the property of

holds for all

holds for all

, it does not matter which value we use to instantiate it. And it indeed satisfies the property:

, it does not matter which value we use to instantiate it. And it indeed satisfies the property:

However, there are no such guarantees in the case not covered by the property:

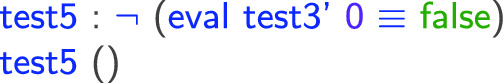

Pointed and Singleton Types:

We now use the above idea to create a version of the  language, which we call

language, which we call  , in which all types are pointed, i.e., for each type t some value v of type t is “in focus”

, in which all types are pointed, i.e., for each type t some value v of type t is “in focus”

. As the goal of the language is to keep track of fractional types, it is sufficient to inherit the multiplicative structure of

. As the goal of the language is to keep track of fractional types, it is sufficient to inherit the multiplicative structure of  . We also need a special kind of pointed type that includes just one value, a singleton type. The singleton types will allow the type system to track the flow of one particular value (the ancilla value), which is exactly what is needed to prove the safety of deallocation. We present the relevant definitions from our formalization and explain each:

. We also need a special kind of pointed type that includes just one value, a singleton type. The singleton types will allow the type system to track the flow of one particular value (the ancilla value), which is exactly what is needed to prove the safety of deallocation. We present the relevant definitions from our formalization and explain each:

Given a set A with an element v, the singleton set containing v is the subset of A whose elements are equal to v. In Agda’s type theory, this is encoded using the

type. For a given type A, and a value v of type A, the type

type. For a given type A, and a value v of type A, the type

A v is inhabited by a choice of point

A v is inhabited by a choice of point  in A, along with a proof that v is equal to

in A, along with a proof that v is equal to  . In other words, it is possible to refer to a singleton value v using several distinct syntactic expressions that all evaluate to v. Put differently, any claim that a value belongs to the singleton type must come with a proof that this value is equal to v. The reciprocal type

. In other words, it is possible to refer to a singleton value v using several distinct syntactic expressions that all evaluate to v. Put differently, any claim that a value belongs to the singleton type must come with a proof that this value is equal to v. The reciprocal type

A v consumes exactly this singleton value. The universe of pointed types

A v consumes exactly this singleton value. The universe of pointed types

contains plain

contains plain  types together with a selection of a value in focus; products of pointed types; singleton types; and reciprocal types. Note that the actual value in focus for reciprocals, i.e., the runtime value of a GC process, is a function that disregards its argument returning the constant value of the unit type. As we show, this is safe, as the type system prevents the GC process being applied to anything but the particular singleton value in question.

types together with a selection of a value in focus; products of pointed types; singleton types; and reciprocal types. Note that the actual value in focus for reciprocals, i.e., the runtime value of a GC process, is a function that disregards its argument returning the constant value of the unit type. As we show, this is safe, as the type system prevents the GC process being applied to anything but the particular singleton value in question.

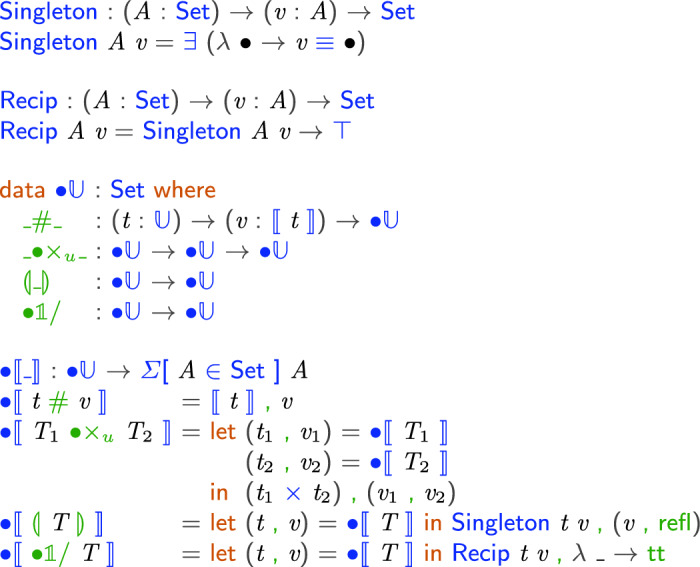

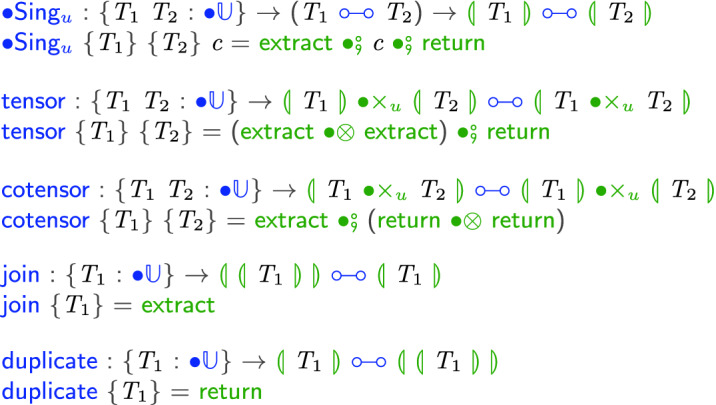

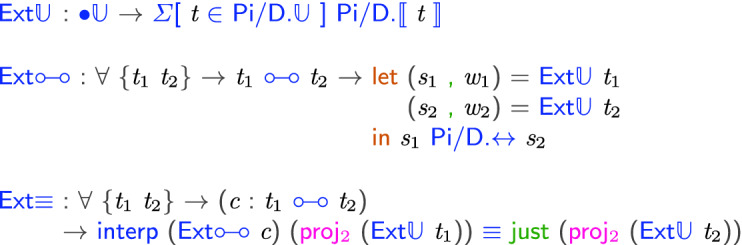

The combinators in the lifted language  consist of all the combinators in the core

consist of all the combinators in the core  language together with their multiplicative structure. The types for

language together with their multiplicative structure. The types for

and

and

are now specialized to guarantee safety of de-allocation as follows. When applying

are now specialized to guarantee safety of de-allocation as follows. When applying

at a pointed type, the current witness value is put in focus in a singleton type and a GC process for that particular singleton type is created. To apply this process using

at a pointed type, the current witness value is put in focus in a singleton type and a GC process for that particular singleton type is created. To apply this process using

the very same singleton value must be the current one.

the very same singleton value must be the current one.

The mediation between general pointed types and singleton types is done via

and

and

, which form a dual monad/comonad pair, from which many structural properties can be derived: specifically a pair of singleton types is a singleton of the pair of underlying types, and a singleton of a singleton is the same singleton.

, which form a dual monad/comonad pair, from which many structural properties can be derived: specifically a pair of singleton types is a singleton of the pair of underlying types, and a singleton of a singleton is the same singleton.

Proposition 1

is both an idempotent strong monad and an idempotent costrong comonad over pointed types.

is both an idempotent strong monad and an idempotent costrong comonad over pointed types.

Proof

The main insight needed is to define the functor

, the

, the

, and the

, and the

:

:

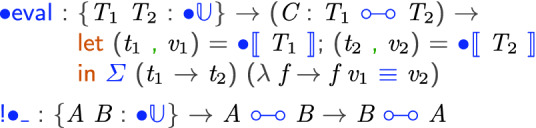

Like for the toy language, evaluation is reflected in the type system, and in this case we have the additional property that evaluation is reversible:

The type of evaluation now states that given a combinator mapping pointed type  to pointed type

to pointed type  where

where  consists of an underlying type

consists of an underlying type  and value

and value  , evaluation succeeds if applying the combinator to

, evaluation succeeds if applying the combinator to  produces

produces  . In other words, the result of evaluation is completely determined by the type system:

. In other words, the result of evaluation is completely determined by the type system:

To summarize, if a combinator expects a singleton type, then it would only typecheck in the lifted language, if it is given the unique value it expects. A particularly intriguing instance of that situation is the following program:

The program takes a value of type

. This would be a GC process specialized to collect another GC process! By collecting this process, the corresponding singleton value is “rematerialized.” At runtime, there would be no information other than the functions that ignore their argument but the type system provides enough guarantees to ensure that this process is well-defined and safe.

. This would be a GC process specialized to collect another GC process! By collecting this process, the corresponding singleton value is “rematerialized.” At runtime, there would be no information other than the functions that ignore their argument but the type system provides enough guarantees to ensure that this process is well-defined and safe.

Extraction of Safe Programs

By lifting programs and their evaluation to the type level, we can naturally leverage the typechecking process to verify properties of interest, including the safe de-allocation of ancillae. One “could” just forget about  and instead use

and instead use  as the programming language for ancilla management. Indeed the dual nature of proofs and programs is more and more exploited in languages like the one used to formalize this paper (Agda).

as the programming language for ancilla management. Indeed the dual nature of proofs and programs is more and more exploited in languages like the one used to formalize this paper (Agda).

However, it is also often the case that constructive proofs are further processed to extract native efficient programs that eschew the overhead of maintaining information needed just for proof invariants. In our case, the question is whether we can extract from a  program, a program in

program, a program in  that uses a simpler type system, a simpler runtime representation, and yet is guaranteed to be safe and hence can run without the runtime checks associated with de-allocation sites. In this section, we show that this indeed the case.

that uses a simpler type system, a simpler runtime representation, and yet is guaranteed to be safe and hence can run without the runtime checks associated with de-allocation sites. In this section, we show that this indeed the case.

We demonstrate this by constructing an extraction map from the syntax of  to

to  . This is fully implemented in the underlying Agda formalization, but we present the most significant highlights. There are three important functions whose signatures are given below:

. This is fully implemented in the underlying Agda formalization, but we present the most significant highlights. There are three important functions whose signatures are given below:

The function

maps a

maps a  type to a

type to a  type and a value in the type. The function

type and a value in the type. The function

maps a

maps a  combinator to a

combinator to a  combinator, whose types are fixed by

combinator, whose types are fixed by

. And finally, the function

. And finally, the function

asserts that the extracted code cannot throw an exception (it must return a

asserts that the extracted code cannot throw an exception (it must return a

value).

value).

Each of these functions has one or two enlightening cases which we explain below. In  the fractional type expresses that it expects a particular value but lacks any mechanisms to enforce this requirement. Thus we have no choice when mapping a fractional type from

the fractional type expresses that it expects a particular value but lacks any mechanisms to enforce this requirement. Thus we have no choice when mapping a fractional type from  to

to  but to use the

but to use the

type with the trivial value:

type with the trivial value:

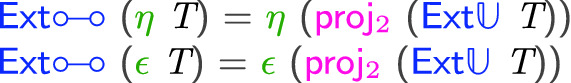

When mapping  combinators to

combinators to  combinators, the main interesting cases are for

combinators, the main interesting cases are for

and

and

. In each of those, we use the values from the pointed type as choices for the ancilla value, and the expectation for the GC process respectively:

. In each of those, we use the values from the pointed type as choices for the ancilla value, and the expectation for the GC process respectively:

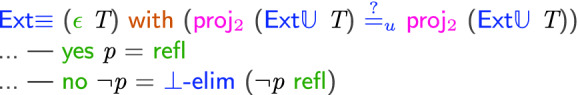

Finally we can prove the correctness of extraction. The punchline is in the following case:

Here, the singleton type in  guarantees that the runtime check cannot fail!

guarantees that the runtime check cannot fail!

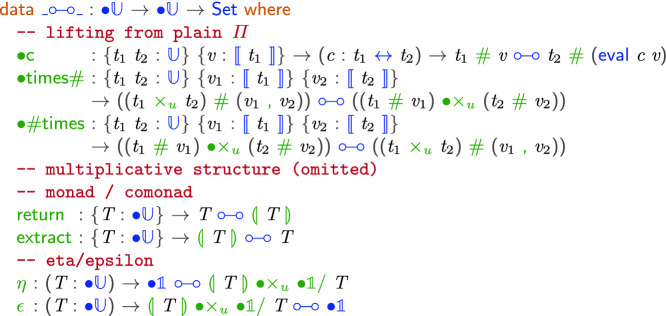

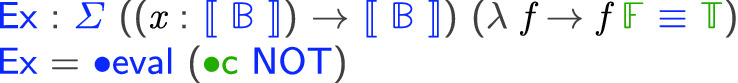

Example

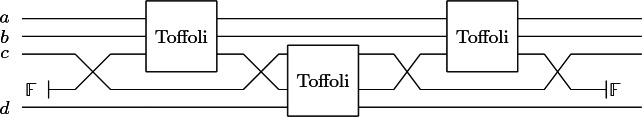

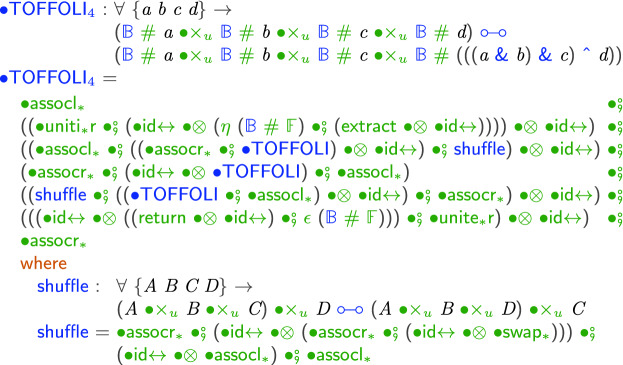

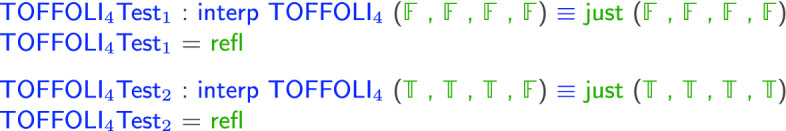

This new language not only allows us to verify circuits but also allows us to merge verification with programming. To clarify this idea, we show how to implement a 4-bit Toffoli gate using proper ancilla management while at the same time proving its correctness.

We start with verification of the Toffoli gate implementation we have in Sect. 3 in  using pattern matching:

using pattern matching:

Since we use the same implementation in all the cases, it does not matter which value we use to instantiate extraction:![]()

Using this as the building block, we can use Toffoli’s construction [25] to construct a 4-bit Toffoli gate using an additional ancilla bit:

The code is written in a conventional  style except for the pervasive lifting to pointed types:

style except for the pervasive lifting to pointed types:

With this construction however, we can verify that the circuit satisfies the specification of 4-bit Toffoli gate and the ancilla bit is correctly garbage collected without pattern matching. And using the extraction mechanism, we obtain a fully verified 4-bit Toffoli gate in  :

:

Note that, the type above has shown that our implementation is independent of any input, so it does not matter which value we use to instantiate the extraction:

Conclusion

We have introduced, in the context of reversible languages, the concept of fractional types as descriptions of specialized GC processes. Although the basic idea is rather simple and intuitive, the technical details needed to reason about individual values are somewhat intricate. The use of fractional types, however, enables a complete elegant type-based solution to the management of ancilla values in reversible programming languages.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for their extensive comments and corrections. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OMA-1936353 and by an EAR grant from the Office of the Vice Provost for Research at Indiana University.

Footnotes

Another interesting interpretation is that these operations correspond to creation and annihilation of entangled particle/antiparticle pairs in quantum physics [19].

Contributor Information

Ivan Lanese, Email: ivan.lanese@gmail.com.

Mariusz Rawski, Email: mariusz.rawski@gmail.com.

Chao-Hong Chen, Email: chen464@indiana.edu.

Vikraman Choudhury, Email: vikraman@indiana.edu.

Jacques Carette, Email: carette@mcmaster.ca.

Amr Sabry, Email: sabry@indiana.edu.

References

- 1.Aaronson, S., Grier, D., Schaeffer, L.: The classification of reversible bit operations. In: Papadimitriou, C.H. (ed.) 8th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2017). Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs), vol. 67, pp. 23:1–23:34. Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik, Dagstuhl (2017)

- 2.Abramsky S. A structural approach to reversible computation. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2005;347(3):441–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tcs.2005.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abramsky S, Haghverdi E, Scott PJ. Geometry of interaction and linear combinatory algebras. Math. Struct. Comput. Sci. 2002;12(5):625–665. doi: 10.1017/S0960129502003730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bénabou J. Catégories avec multiplication. C. R. de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris. 1963;256(9):1887–1890. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bénabou J. Algèbre élémentaire dans les catégories avec multiplication. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1964;258(9):771–774. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benton PN. A mixed linear and non-linear logic: proofs, terms and models. In: Pacholski L, Tiuryn J, editors. Computer Science Logic; Heidelberg: Springer; 1995. pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowman, W.J., James, R.P., Sabry, A.: Dagger traced symmetric monoidal categories and reversible programming. In: RC (2011)

- 8.Carette J, Sabry A. Computing with semirings and weak rig groupoids. In: Thiemann P, editor. Programming Languages and Systems; Heidelberg: Springer; 2016. pp. 123–148. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiore MP, Di Cosmo R, Balat V. Remarks on isomorphisms in typed calculi with empty and sum types. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic. 2006;141(1–2):35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.apal.2005.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiore, M.: Isomorphisms of generic recursive polynomial types. In: POPL, pp. 77–88. ACM (2004)

- 11.Fredkin E, Toffoli T. Conservative logic. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1982;21(3):219–253. doi: 10.1007/BF01857727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, A.S., Lumsdaine, P.L., Ross, N.J., Selinger, P., Valiron, B.: Quipper: a scalable quantum programming language. In: Proceedings of the 34th ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation, PLDI 2013, pp. 333–342. ACM, New York (2013)

- 13.James, R.P., Sabry, A.: Information effects. In: POPL, pp. 73–84. ACM (2012)

- 14.James RP, Sabry A. Isomorphic interpreters from logically reversible abstract machines. In: Glück R, Yokoyama T, editors. Reversible Computation; Heidelberg: Springer; 2013. pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly GM. Many-variable functorial calculus. I. In: Kelly GM, Laplaza M, Lewis G, Mac Lane S, editors. Coherence in Categories. Heidelberg: Springer; 1972. pp. 66–105. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnaswami, N.R., Pradic, P., Benton, N.: Integrating dependent and linear types. In: POPL 2015 (2015)

- 17.Laplaza ML. Coherence for distributivity. In: Kelly GM, Laplaza M, Lewis G, Mac Lane S, editors. Coherence in Categories. Heidelberg: Springer; 1972. pp. 29–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLane S. Natural associativity and commutativity. Rice Inst. Pamphlet Rice Univ. Stud. 1963;49(4):28–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panangaden P, Paquette É. A categorical presentation of quantum computation with anyons. In: Coecke B, editor. New Structures for Physics. Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. pp. 983–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose, E.: Arrow: A Modern Reversible Programming Language. Oberlin College (2015). https://books.google.com/books?id=sX1vnQAACAAJ

- 21.Sparks, Z., Sabry, A.: Superstructural reversible logic. In: 3rd International Workshop on Linearity (2014)

- 22.The Univalent Foundations Program: Homotopy Type Theory: Univalent Foundations of Mathematics. Institute for Advanced Study (2013). http://homotopytypetheory.org/book

- 23.Thomsen, M.K., Axelsen, H.B.: Interpretation and programming of the reversible functional language RFUN. In: Proceedings of the 27th Symposium on the Implementation and Application of Functional Programming Languages, IFL 2015. Association for Computing Machinery, New York (2015). 10.1145/2897336.2897345

- 24.Thomsen MK, Kaarsgaard R, Soeken M. Ricercar: a language for describing and rewriting reversible circuits with ancillae and its permutation semantics. In: Krivine J, Stefani J-B, editors. Reversible Computation; Cham: Springer; 2015. pp. 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toffoli T. Reversible computing. In: de Bakker J, van Leeuwen J, editors. Automata, Languages and Programming; Heidelberg: Springer; 1980. pp. 632–644. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoyama T, Axelsen HB, Glück R. Towards a reversible functional language. In: De Vos A, Wille R, editors. Reversible Computation; Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. pp. 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokoyama, T., Glück, R.: A reversible programming language and its invertible self-interpreter. In: PEPM, pp. 144–153. ACM (2007)