Abstract

目的

比较初诊急性髓系白血病(AML)患者诱导化疗后骨髓抑制期应用聚乙二醇化重组人G-CSF(PEG-rhG-CSF)与普通重组人G-CSF(rhG-CSF)促进中性粒细胞或白细胞恢复的时间。同时比较两种药物对患者感染发生率、住院时间的影响。

方法

采用前瞻性随机对照研究方法,将2014年8月至2017年12月间符合入组条件的初诊AML患者诱导治疗后按1∶1比例随机分成两组:PEG-rhG-CSF组和rhG-CSF组。对比分析两组患者中性粒细胞计数(ANC)或WBC恢复时间、感染发生率和住院时间。

结果

共入组初诊AML患者60例,PEG-rhG-CSF组30例,rhG-CSF组30例。两组患者除性别构成外,在年龄、化疗方案、化疗前ANC、WBC、诱导化疗疗效方面差异均无统计学意义(P值均>0.05)。PEG-rhG-CSF组患者与rhG-CSF组患者的ANC、WBC恢复中位时间分别为19(14~35)d、19(15~26)d,差异无统计学意义(t=0.580,P=0.566)。PEG-rhG-CSF组、rhG-CSF组患者骨髓抑制期感染的发生率分别为90.0%、93.3%,差异无统计学意义(P=1.000)。两组患者的中位住院时间分别为20.5(17~49)d、21(19~43)d,差异无统计学意义(P=0.530)。

结论

AML患者诱导治疗后应用PEG-rhG-CSF与rhG-CSF无论在ANC或WBC恢复时间,还是在感染的发生率及住院时间均相当。

Keywords: 粒细胞集落刺激因子, 聚乙二醇化, 中性粒细胞减少, 白血病,髓样,急性, 诱导化疗

Abstract

Objective

To compare the time of the recovery of neutrophils or leukocytes by pegylated recombinant human granulocyte stimulating factor (PEG-rhG-CSF) or common recombinant human granulocyte stimulating factor (rhG-CSF) in the myelosuppressive phase after induction chemotherapy in newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients. At the same time, the incidences of infection and hospitalization were compared.

Methods

A prospective randomized controlled trial was conducted in patients with newly diagnosed AML who met the enrollment criteria from August 2014 to December 2017. The patients were randomly divided into two groups according to a 1:1 ratio: PEG-rhG-CSF group and rhG-CSF group. The time of neutrophil or leukocyte recovery, infection rate and hospitalization interval were compared between the two groups.

Results

60 patients with newly diagnosed AML were enrolled: 30 patients in the PEG-rhG-CSF group and 30 patients in the rhG-CSF group. There were no significant differences in age, chemotherapy regimen, pre-chemotherapy ANC, WBC, and induction efficacy between the two groups (P>0.05). The median time (range) of ANC or WBC recovery in patients with PEG-rhG-CSF and rhG-CSF were 19 (14–35) d and 19 (15–26) d, respectively, with no statistical difference (P=0.566). The incidences of infection in the PEG-rhG-CSF group and the rhG-CSF group were 90.0%and 93.3%, respectively, and there was no statistical difference (P=1.000). The median days of hospitalization (range) was 20.5 (17–49) days and 21 (19–43) days, respectively, with no statistical difference (P=0.530).

Conclusion

In AML patients after induction therapy, there was no significant difference between the application of PEG-rhG-CSF and daily rhG-CSF in ANC or WBC recovery time, infection incidence and hospitalization time.

Keywords: Granulocyte stimulating factor; Pegylation; Neutropenia; Acute myeloid leukemia; Chemotherapy, induction

急性髓系白血病(AML)以骨髓、外周血或其他组织中髓系原始细胞克隆性增殖为主要特点[1]。中性粒细胞减少是AML患者化疗过程中一种常见的并发症,使患者治疗过程中易合并严重感染,影响进一步治疗,甚至导致死亡。重组人G-CSF(rhG-CSF)能促进中性粒细胞恢复,降低中性粒细胞减少的严重程度并缩短其持续时间,从而降低AML患者严重感染并发症的发生率[2]–[3]。目前临床常用的rhG-CSF半衰期短,需每日注射,给患者和医务工作者带来极大的不便[4]。聚乙二醇化重组人G-CSF(PEG-rhG-CSF)是一种长效的G-CSF,由于聚乙二醇化的特性,主要通过中性粒细胞介导清除,在实体瘤患者中半衰期长达47 h,用于预防化疗后中性粒细胞减少的疗效已非常明确[5]–[7]。PEG-rhG-CSF在AML中的应用在国外已有少量报道[8]–[13],在我国仅见PEG-rhG-CSF在AML干细胞移植术后应用的报道[14]。为了明确PEG-rhG-CSF在我国AML中的疗效和安全性,以中国医学科学院血液病医院为研究中心,于2014年8月至2017年12月对PEG-rhG-CSF进行了一项单中心、随机对照临床研究,现将结果报告如下。

病例与方法

1.病例:2014年8月至2017年12月间我院住院治疗的60例初诊AML患者纳入研究。入组标准:①骨髓细胞形态学、免疫学、分子生物学、细胞遗传学确诊的除急性早幼粒细胞白血病以外的初诊AML;②年龄≥18岁且≤55岁,男女不限;③预期生存时间在用药后≥40 d;④实验室检查指标符合以下要求:总胆红素≤正常值上限1.5倍,AST和ALT≤正常值上限2.5倍,血肌酐<正常值上限2倍,心肌酶<正常值上限2倍;⑤诱导方案为HAD方案(高三尖杉酯碱2 mg/m2×7 d,阿糖胞苷100 mg/m2×7 d,柔红霉素40 mg/m2×3 d)或DA方案(柔红霉素60 mg/m2×3 d,阿糖胞苷100 mg/m2×7 d);⑥美国东部肿瘤协作组(ECOG)体力状况评分≤2分;⑦在所有具体研究程序开始前必须签署知情同意书。排除标准:①复发患者;②WHO AML分类属不另作分类的AML亚类中急性全髓增殖症伴骨髓纤维化及髓系肉瘤患者;③同时患有其他脏器恶性肿瘤(需治疗者);④PEG-rhG-CSF或rhG-CSF药物过敏或不耐受患者;⑤肝肾功能明显异常,超出标准;⑥存在可能干扰受试者参与研究或研究结果评价的药物滥用、医学、心理或社会情况;⑦目前有活动性感染、发热患者,怀孕期或哺乳期女性患者,育龄妇女拒绝接受避孕措施者;⑧3个月内采用其他试用药物或接受其他临床试验者;⑨研究者认为不适合入组者。本研究获得中国医学科学院血液病医院伦理委员会批准。

2.研究药物:PEG-rhG-CSF和rhG-CSF均为石药集团百克(山东)生物制药有限公司产品,并质检合格,PEG-rhG-CSF(商品名津优力®)批号:201302P01、4620140902、4620170707、4620170708;rhG-CSF(商品名津恤力®)批号:201301G02、9620140919、9620150102、9620150307、9620161108、9620170401。

3.研究设计:使用SAS软件制定随机表,将患者按1∶1随机分配至PEG-rhG-CSF组和rhG-CSF组:①PEG-rhG-CSF组:于停化疗第5天应用PEG-rhG-CSF 1次,体重≥45 kg者每次6 mg,体重<45 kg者每次3 mg;②rhG-CSF组:于停化疗第5天开始应用rhG-CSF 5 µg·kg−1·d−1,直至中性粒细胞绝对计数(ANC)≥0.5×109/L和(或)WBC≥1.0×109/L。

4.观察指标及不良反应评价标准:收集患者住院期间所有临床资料,观察两组患者ANC或WBC恢复时间[化疗第1天至ANC≥0.5×109/L和(或)WBC≥1.0×109/L的时间],感染发生率和严重程度,住院时间(化疗第1天至出院的持续时间)。不良反应采用《常见不良事件评价标准(CTCAE)》4.03版进行评价。

5.统计学处理:所有数据采用SAS 9.4软件进行统计学分析。P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义,两组患者基线和疗效指标的比较均采用符合方案数据集(PPS)。主要指标中,ANC或WBC恢复时间组间比较,采用协方差分析模型,ANC或WBC恢复时间为因变量,组别为自变量,基线ANC或WBC为协变量。采用Kaplan-Meier法估计中位ANC或WBC恢复时间,采用Log-rank检验进行组间比较,并绘制恢复曲线。感染的发生率及严重程度采用矫正卡方检验进行组间比较,住院时间采用t检验进行组间比较。

结果

1.患者基本情况:2014年8月至2017年12月间共入组初诊AML患者60例,PEG-rhG-CSF组30例,rhG-CSF组30例。两组患者除性别构成外,在年龄、化疗方案、初诊ANC、WBC、诱导疗效方面差异均无统计学意义(P值均>0.05)。患者基本情况详见表1。

表1. 聚乙二醇化重组人G-CSF(PEG-rhG-CSF)与普通重组人G-CSF(rhG-CSF)组患者基本情况.

| 特征 | PEG-rhG-CSF组(30例) | rhG-CSF组(30例) | 统计量 | P值 |

| 年龄[岁,M(范围)] | 34(18~54) | 39.5(18~54) | 0.184(t值) | 0.667 |

| 性别[例(%)] | 4.444(χ2值) | 0.035 | ||

| 女 | 22(73.3) | 14(46.7) | ||

| 男 | 8(26.7) | 16(53.3) | ||

| ECOG评分[例(%)] | 0.336(χ2值) | 1.000 | ||

| 0分 | 12(40.0) | 13(43.3) | ||

| 1分 | 17(56.7) | 16(53.3) | ||

| 2分 | 1(3.3) | 1(3.3) | ||

| 诱导化疗方案[例(%)] | 0.069(χ2值) | 0.793 | ||

| HAD | 17(56.7) | 18(60.0) | ||

| DA | 13(43.3) | 12(40.0) | ||

| 初诊ANC[×109/L,M(范围)] | 0.76(0.00~27.18) | 0.88(0.06~7.19) | 0.684(t值) | 0.408 |

| 初诊WBC[×109/L,M(范围)] | 7.08(0.74~158.30) | 14.97(1.20~70.64) | 0.673(t值) | 0.412 |

| 诱导疗效评价[例(%)] | 2.099(χ2值) | 0.885 | ||

| CR | 23(76.7) | 23(76.7) | ||

| CRi | 1(3.3) | 1(3.3) | ||

| PR | 1(3.3) | 2(6.7) | ||

| NR | 5(16.7) | 3(10.0) | ||

| 失访 | 0(0) | 1(3.3) |

注:ECOG:美国东部肿瘤协作组;HAD:高三尖杉酯碱+阿糖胞苷+柔红霉素;DA:柔红霉素+阿糖胞苷;ANC:中性粒细胞绝对计数;CR:完全缓解;CRi:伴血细胞未恢复的完全缓解;PR:部分缓解;NR:未缓解

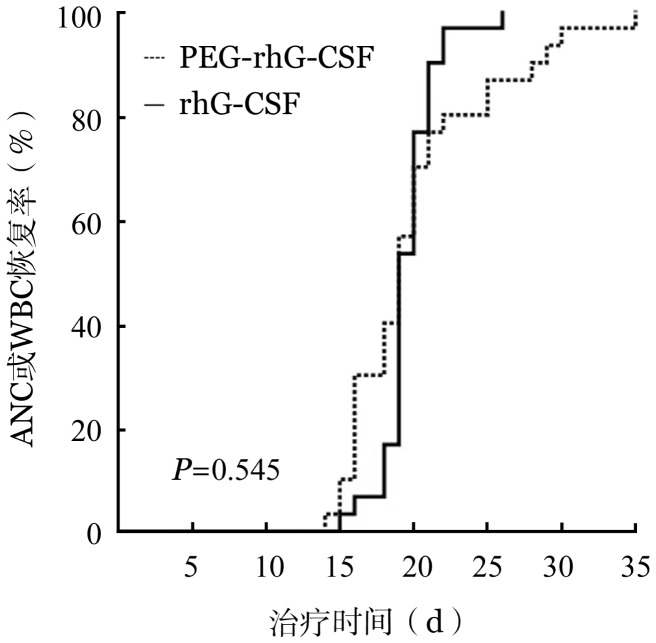

2.中性粒细胞或白细胞恢复情况:诱导化疗后,PEG-rhG-CSF组与rhG-CSF组的ANC最低点均在停化疗第5天出现,分别为0.03(0.00~1.23)×109/L与0.09(0~0.44)×109/L,均发生了Ⅳ度粒细胞缺乏。停化疗第5天给予PEG-rhG-CSF或rhG-CSF后,两组的ANC或WBC恢复时间中位值分别为19(14~35)d和19(15~26)d,差异无统计学意义(t=0.580,P=0.566)。诱导治疗后两组的ANC或WBC恢复曲线见图1。

图1. 聚乙二醇化重组人G-CSF(PEG-rhG-CSF)与普通重组人G-CSF(rhG-CSF)组患者ANC或WBC恢复曲线.

3.感染发生情况:PEG-rhG-CSF组与rhG-CSF组所有级别的感染发生率分别为90.0%(27例)与93.3%(28例),差异无统计学意义(P=1.000)。感染部位大多为上呼吸道、肺部和齿龈。PEG-rhG-CSF组有4例(14.8%)患者发生了Ⅱ度感染,23例(85.2%)患者发生了Ⅲ度及以上感染;rhG-CSF组发生的所有感染均为Ⅲ度及以上感染,两组的感染程度差异无统计学意义(P=0.110)。

4.住院时间:PEG-rhG-CSF组、rhG-CSF组中位住院时间分别为20.5(17~49)d、21(19~43)d,差异无统计学意义(P=0.530)。

5.安全性:所有患者均进行安全性评估,两组患者均未发生严重药物相关性的不良反应。骨痛不良反应方面,PEG-rhG-CSF组1例(3.3%)发生轻度骨关节疼痛,rhG-CSF组5例(16.7%)发生轻度骨关节疼痛,差异无统计学意义(P=0.200)。两组均未出现因不耐受而停用PEG-rhG-CSF/rhG-CSF的病例。

讨论

近年来AML的发病率呈逐年上升的趋势,随着化疗方案的改进、化疗药物剂量的加大、移植的应用,AML的疗效近年来得到明显的提高。由于疾病本身和化疗的原因,AML患者在治疗过程中常合并中性粒细胞减少,使患者治疗过程中易合并严重感染,影响进一步治疗,甚至导致死亡。患者在骨髓抑制期应用rhG-CSF可加速骨髓粒系细胞的增殖,促进骨髓造血功能恢复,可有效降低发热、感染等并发症的发生率[15]–[17]。

在本研究中使用的PEG-rhG-CSF注射液,由一个相对分子质量为20×103的PEG分子选择性地与rhG-CSF蛋白质N末端定点交联而成。PEG-rhG-CSF为长效制剂,在肿瘤患者血浆中半衰期可达47 h,每个化疗周期一般只需用药1次。已有研究报道PEG-rhG-CSF在预防肿瘤患者化疗后中性粒细胞减少症中的疗效肯定[18]–[23],且与每日使用rhG-CSF的疗效相当[24]。

本研究两组患者中,PEG-rhG-CSF组和rhG-CSF组的ANC或WBC中位恢复时间分别为19(14~35)d和19(15~26)d,差异无统计学意义(P=0.566)。两组患者骨髓抑制期感染的发生率分别为90.0%和93.3%,差异无统计学意义(P=1.000),3度以上感染发生率分别为76.7%和93.3%,差异无统计学意义(P=0.110)。两组患者的中位住院时间分别为20.5(17~49)d和21(19~43)d,差异亦无统计学意义(P=0.530)。与既往文献[25]报道基本一致。而rhG-CSF组中位给药时间为10(5~16)d,PEG-rhG-CSF组只需使用一次。

在安全性方面,两组的不良反应发生率均很低且为轻度可耐受,并且两组均未出现因不耐受而退出试验的病例。PEG-rhG-CSF最常见的不良反应为骨痛,本研究仅发生1例(3.3%)轻度关节疼痛,低于文献报道的发生率(7.0%)[25],也低于试验中rhG-CSF组的发生率。

综上所述,PEG-rhG-CSF在我国AML患者中安全性良好,不影响诱导化疗疗效,能够有效降低AML患者重度中性粒细胞减少症的发生、发热性中性粒细胞减少症的发生和持续时间,确保化疗按时按量执行。同时应用简便,减少了注射次数,相应减少患者痛苦,减轻临床医护人员负担,为AML患者诱导化疗后中性粒细胞减少症的治疗提供了新的选择。

References

- 1.Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet[J] Blood. 2010;115(3):453–474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehrnbecher T, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, et al. Prophylactic human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after induction therapy in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia[J] Blood. 2007;109(3):936–943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore JO, Dodge RK, Amrein PC, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (filgrastim) accelerates granulocyte recovery after intensive postremission chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with aziridinyl benzoquinone and mitoxantrone: Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 9022[J] Blood. 1997;89(3):780–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Der Auwera P, Platzer E, Xu ZX, et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of single doses of subcutaneous pegylated human G-CSF mutant (Ro 25-8315) in healthy volunteers: comparison with single and multiple daily doses of filgrastim[J] Am J Hematol. 2001;66(4):245–251. doi: 10.1002/ajh.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.石 远凯, 许 建萍, 吴 昌平, et al. 聚乙二醇化重组人粒细胞刺激因子预防化疗后中性粒细胞减少症的多中心上市后临床研究[J] 中国肿瘤临床. 2017;44(14):679–684. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-8179.2017.14.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.黄 慧强, 白 冰, 高 玉环, et al. 应用聚乙二醇化重组人G-CSF预防淋巴瘤患者化疗后中性粒细胞减少: 一项前瞻、多中心、开放性临床研究[J] 中华血液学杂志. 2017;38(10):825–830. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2017.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.江 泽飞, 许 凤锐, 樊 菁, et al. 聚乙二醇化重组人粒细胞刺激因子预防乳腺癌患者化疗后中性粒细胞减少的多中心随机对照Ⅳ期临床观察[J] 中华医学杂志. 2018;98(16):1231–1235. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2018.16.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derbel O, Cannas G, Le QH, et al. A single dose pegfilgrastim for supporting neutrophil recovery in patients treated for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia by the EMA 2000 schedule[J] Hematology. 2010;15(3):125–131. doi: 10.1179/102453309X12583347113654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiegl M, Hiddemann W, Braess J. Use of pegylated recombinant filgrastim (Pegfilgrastim) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: pharmacokinetics and impact on leukocyte recovery[J] Leukemia. 2008;22(6):1284–1285. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braess J, Spiekermann K, Staib P. Dose-dense induction with sequential high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantone (S-HAM) and pegfilgrastim results in a high efficacy and a short duration of critical neutropenia in de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a pilot study of the AMLCG[J] Blood. 2009;113(17):3903–3910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kam G, Yiu R, Loh Y, et al. Impact of pegylated filgrastim in comparison to filgrastim for patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) on high-dose cytarabine (HIDAC) consolidation chemotherapy[J] Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(3):643–649. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaramillo S, Benner A, Krauter J, et al. Condensed versus standard schedule of high-dose cytarabine consolidation therapy with pegfilgrastim growth factor support in acute myeloid leukemia[J] Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(5):e564. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperr WR, Herndlhofer S, Gleixner K, et al. Intensive consolidation with G-CSF support: Tolerability, safety, reduced hospitalization, and efficacy in acute myeloid leukemia patients ≥60 years[J] Am J Hematol. 2017;92(10):E567–E574. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.杨 帆, 孙 雪冬, 袁 磊, et al. 聚乙二醇化G-CSF与重组人G-CSF促进恶性血液病异基因造血干细胞移植后造血恢复的对比研究[J] 中华血液学杂志. 2017;38(10):831–836. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.张 东辉, 贺 立山, 李 志英, et al. 粒细胞集落刺激因子治疗急性髓性白血病的疗效及安全性[J] 山东医药. 2003;43(16):25–26. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2003.16.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.施 菊妹. 重组人粒细胞集落刺激因子在治疗急性髓细胞白血病中的应用[J] 南通医学院学报. 1999;19(4):395–396. [Google Scholar]

- 17.沈 志祥, 武 永吉. DA方案和粒细胞集落刺激因子联合应用治疗急性髓细胞白血病的疗效观察[J] 中华血液学杂志. 1997;18(4):211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozma CM, Dickson M, Chia V, et al. Trends in neutropenia-related inpatient events[J] J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(3):149–155. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simona B, Cristina R, Luca N, et al. A single dose of Pegfilgrastim versus daily Filgrastim to evaluate the mobilization and the engraftment of autologous peripheral hematopoietic progenitors in malignant lymphoma patients candidate for high-dose chemotherapy[J] Transfus Apher Sci. 2010;43(3):321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burris HA, Belani CP, Kaufman PA, et al. Pegfilgrastim on the same day versus next day of chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: results of four multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase II studies[J] J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(3):133–140. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zwick C, Hartmann F, Zeynalova S, et al. Randomized comparison of pegfilgrastim day 4 versus day 2 for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced leukocytopenia[J] Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1872–1877. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mey UJ, Maier A, Schmidt-Wolf IG, et al. Pegfilgrastim as hematopoietic support for dose-dense chemoimmunotherapy with R-CHOP-14 as first-line therapy in elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma[J] Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(7):877–884. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0201-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pro B, Fayad L, McLaughlin P, et al. Pegfilgrastim administered in a single fixed dose is effective in inducing neutrophil count recovery after paclitaxel and topotecan chemotherapy in patients with relapsed aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma[J] Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(3):481–485. doi: 10.1080/10428190500305802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henk HJ, Becker L, Tan H, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pegfilgrastim, filgrastim, and sargramostim prophylaxis for neutropenia-related hospitalization: two US retrospective claims analyses[J] J Med Econ. 2013;16(1):160–168. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.734885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sierra J, Szer J, Kassis J, et al. A single dose of pegfilgrastim compared with daily filgrastim for supporting neutrophil recovery in patients treated for low-to-intermediate risk acute myeloid leukemia: results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 trial[J] BMC Cancer. 2008;8:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]