Abstract

Introduction

Understanding patients’ preferences for long-acting injectable (LAI) or oral antipsychotics (pills) could help reduce potential barriers to LAI use in schizophrenia.

Methods

Post hoc analyses were conducted from a double-blind, randomized, non-inferiority study (NCT01515423) of 3-monthly vs 1-monthly paliperidone palmitate in patients with schizophrenia. Data from the Medication Preference Questionnaire, administered on day 1 (baseline; open-label stabilization phase), were analyzed. The questionnaire includes four sets of items: 1) reasons for general treatment preference based on goals/outcomes and preference for LAI vs pills based on 2) personal experience, 3) injection-site (deltoid vs gluteal), 4) dosing frequency (3-monthly vs 1-monthly). A logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the effect of baseline variables on preference (LAIs or pills).

Results

Data from 1402 patients were available for analysis. Patients who preferred LAIs recognized these outcomes as important: “I feel more healthy” (57%), “I can get back to my favorite activities” (56%), “I don’t have to think about taking my medicines” (54%). Most common reasons for medication preference (LAI vs pills) were: “LAIs/pills are easier for me” (67% vs 18%), “more in control/don’t have to think about taking medicine” (64% vs 14%), “less pain/sudden symptoms” (38% vs 18%) and “less embarrassed” (0% vs 46%). Majority of patients (59%) preferred deltoid over gluteal injections (reasons: faster administration [63%], easier [51%], less embarrassing [44%]). In total, 50% of patients preferred 3-monthly over 1-monthly (38%) or every day (3%) dosing citing reasons: fewer injections [96%], fewer injections are less painful [84%], and fewer doctor visits [80%]. From logistic regression analysis, 77% of patients preferred LAI over pills; culture and race appeared to play a role in this preference.

Conclusion

Patients who preferred LAI antipsychotics prioritized self-empowerment and quality-of-life-related goals. When given the option, patients preferred less-frequent, quarterly injections over monthly injections and daily oral medications.

Keywords: long-acting injectable antipsychotics, oral antipsychotics, paliperidone palmitate, patient preference, quality-of-life

Introduction

Medication nonadherence and subsequent relapses amplify the disease burden and contribute to worsening symptomatology and prognosis in schizophrenia.1,2 Continuous antipsychotic treatment is therefore a formidable goal in schizophrenia management. Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics reduce adherence demands by eliminating the need for daily dosing and maintaining stable therapeutic drug levels for longer intervals and lower the risk of relapse and rehospitalization due to treatment discontinuation.2–4 Despite these benefits, LAI prescription rates in clinical practice in most Western countries are low and vary between 20% and 33% and are restricted to patients who are previously nonadherent to oral antipsychotics and those who prefer and most likely would accept LAIs.5–8 The disparity in percentage of patients currently being treated with LAIs and the rate of nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia (40% to 80%) indicates underutilization of LAIs.9

Patients’ perceptions and attitudes are critical factors that determine medication adherence and are also recognized as potential barriers to LAI usage, thus underscoring the relevance of patient-centric care in schizophrenia.10–12 Although several studies have centered on clinician’s and caregiver’s perspective, fewer studies highlight the perspective of patients with schizophrenia on choice of LAIs or oral antipsychotic pills. In a population-based survey of patients with schizophrenia, patients’ acceptance of LAI antipsychotics was found to be higher than the prescription rate.13 Further, a dichotomy in appraising treatment goals has been observed between patients and clinicians that could have an impact on treatment selection and continuity.14,15 Given the wide-ranging symptomatic and functional effects of antipsychotic medications, understanding the patient’s treatment expectations and medication preference could help achieve concordance between treatment goals, enhance patient engagement and facilitate utilization of LAIs in schizophrenia.15

The aim of this analysis was to assess factors that determine patient’s preference for LAI or oral antipsychotics (pills) in schizophrenia. Patient-reported outcomes to the Medication Preference Questionnaire (MPQ) collected during a phase 3, randomized, double-blind (DB) study of 3-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP3M) and 1-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) were analyzed to assess preference to LAI versus oral antipsychotics (pills) in schizophrenia.

Patients and Methods

Study Overview

This was a post hoc analysis of MPQ data derived from a phase 3 (NCT01515423), randomized, multicenter, non-inferiority study of PP3M versus PP1M.16 Detailed methods have been reported elsewhere. Briefly, the study included adult patients with schizophrenia (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, DSM-IV criteria), a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score between 70 and 120 at screening and baseline and worsening of symptoms. After an approximately 3-week screening phase, all patients were stabilized on PP1M in a 17-week open-label (OL) phase. Clinically stabilized patients were then randomized to receive fixed dose of either PP3M (175, 263, 350, or 525 mg eq.) or PP1M (50, 75, 100, or 150 mg eq.) as deltoid or gluteal injections in the 48-week DB treatment phase. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the relevant Independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board (listed in Supplementary material) for each country in which the trial was conducted and all patients provided written informed consent.

The MPQ was administered on day 1 (first visit of the OL phase); day 120 (first visit of the DB phase); and at the end of study visit to assess medication preferences of patients for PP3M relative to prior oral and/or LAI antipsychotics.

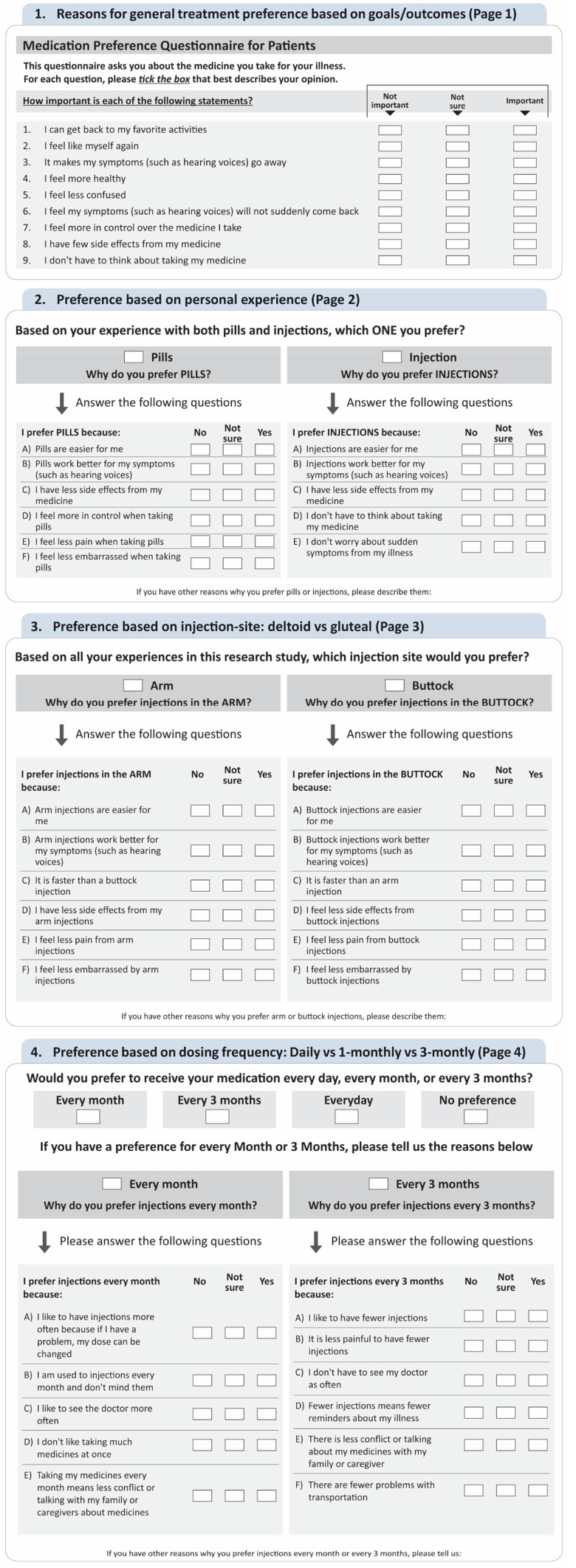

Medication Preference Questionnaire

The MPQ is a 4-page questionnaire to be completed by patients (Figure 1). Items in page 1 gauged the importance of general treatment goals/outcomes including symptoms, side effects, and general well-being with regard to treatment preference. Responses were captured as “Important,” “Not Important” and “Not sure.” In page 2, patients were asked to indicate specific reasons (eg convenience, pain, etc.) for their preference for LAI or oral/pills. Page 3 included questions to understand the reasons (eg pain, comfort, etc.) for the patient’s preference for deltoid vs gluteal injections. Items on page 4 collected information on patient’s preference based on dosing frequency (daily, every month or every 3 months) and reasons for preference for 1-monthly vs 3-monthly injections. Responses for items on pages 2, 3 and 4 were captured as “Yes,” “No” and “Not sure.”

Figure 1.

Medication preference questionnaire.

Analysis

MPQ data collected on day 1 were used for this post hoc analysis to minimize bias. Since the study disallowed LAI use within 4 weeks prior to entry, we focused our MPQ analyses on the day 1 visit. As the study utilized a double-dummy technique, the baseline (day 1) visit is the only timepoint when patients would not have received any study medication. Patients were further grouped by baseline preference (either oral or LAI).

Individual items on page 1 were grouped to give a clear understanding on the importance of specific treatment outcomes for patients. The patient preference domains were grouped into categories as follows: 1) patient empowerment 2) quality-of-life and treatment adherence and 3) symptom improvement. The categories were created in accordance with clinical judgment based largely on how the individual MPQ items covered the same construct.

Responses of “Not sure” were grouped with “Not Important” (page 1) or “No” (pages 2/3/4) under the premise that any non-positive value is considered a negative response.

Descriptive analyses of the baseline variables were performed with categorical variables summarized as frequencies and proportions and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. Patients’ responses to items of MPQ were summarized descriptively.

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the effect of selected baseline variables on preference for LAIs/pills. Continuous variables were initially categorized (Table 1). These categorized baseline predictor variables were first fitted individually into each model to assess their univariate (unadjusted) effect, and then together to assess their adjusted effect on preference for LAIs/pills.

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Preference | Total n=1402 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| LAI n=1082 |

Oral (Pills) n=320 |

||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 38.2 (11.8) | 39.0 (12.1) | 38.4 (11.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Men | 575 (53.1) | 187 (58.4) | 762 (54.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 640 (59.1) | 120 (37.5) | 760 (54.2) |

| Black | 64 (5.9) | 47 (14.7) | 111 (7.9) |

| Others | 378 (34.9) | 153 (47.8) | 531 (37.9) |

| Age at schizophrenia diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 27.6 (9.1) | 27.2 (9.3) | 27.5 (9.2) |

| Number of prior hospitalizations, n (%) | |||

| None | 340 (31.4) | 105 (32.8) | 445 (31.7) |

| One | 329 (30.4) | 92 (28.8) | 421 (30.0) |

| ≥Two | 413 (38.2) | 123 (38.4) | 536 (38.2) |

| Duration of prior hospitalizations (days), n (%) | |||

| 0–14 | 419 (47.6) | 124 (51.4) | 543 (48.4) |

| 15–30 | 102 (11.6) | 26 (10.8) | 128 (11.2) |

| >30 | 359 (40.8) | 91 (37.8) | 450 (40.1) |

| BMI, n (%) | |||

| Normal | 472 (43.6) | 140 (43.8) | 612 (43.7) |

| Overweight | 351 (32.4) | 101 (31.6) | 452 (32.2) |

| Obese | 259 (23.9) | 79 (24.7) | 338 (24.1) |

| Country/Region, n (%) | |||

| North America (USA) | 97 (8.9) | 67 (20.9) | 164 (11.7) |

| Europe | 557 (51.5) | 76 (23.8) | 633 (45.1) |

| Other | 428 (39.6) | 177 (55.3) | 605 (43.2) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; USA, United States of America.

Results

Patient Disposition

Of 1429 patients who enrolled and were dosed in the OL phase, data were available for 1402 patients for this analysis. Patients had a mean (SD) age of 38.4 (11.9) years and the majority were men (55%). Patients were mostly White (54%); 8% of patients were Black or African American and 38% belonged to other races (mostly Asian). Twelve percent (12%) of patients were from the United States (Table 1).

Medication Preference Questionnaire

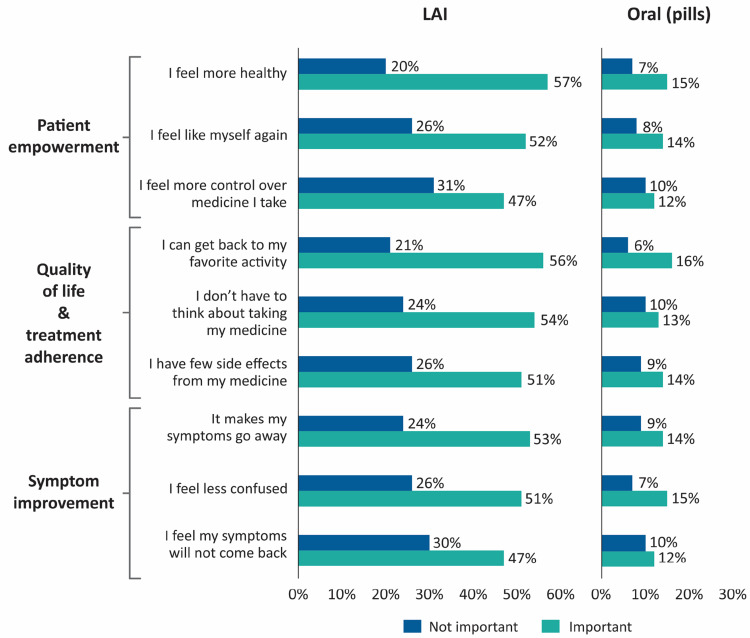

Page 1: General Treatment Preference Based on Goals/Outcomes

Patients who preferred LAIs regarded these outcomes as important: “I feel more healthy” (57%), “I can get back to my favorite activities” (56%), “I don’t have to think about taking my medicines” (54%) (Figure 2). Overall, outcomes related to patient empowerment and quality-of-life were regarded as important among patients who preferred LAIs.

Figure 2.

Treatment goals/outcomes cited as important or not important for medication preference.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable.

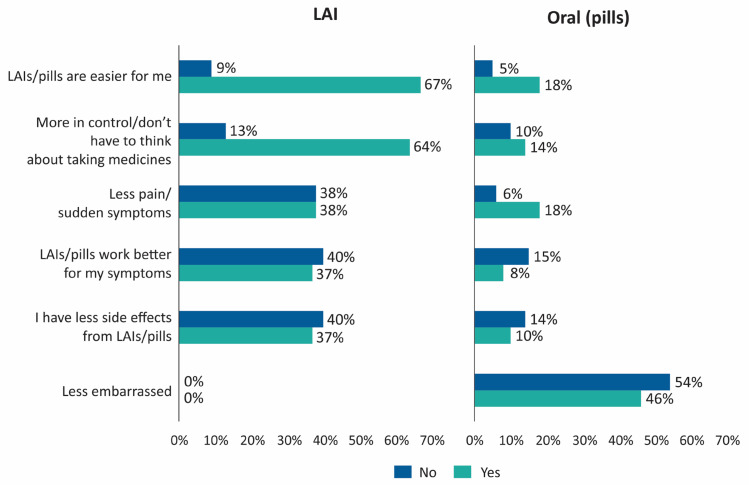

Page 2: Preference Based on Personal Experience

Most common reasons quoted for medication preference (LAI vs pills) were: “LAIs/pills are easier for me” (67% vs 18%), “more in control/don’t have to think about taking medicine” (64% vs 14%), “less pain/sudden symptoms” (38% vs 18%) and “less embarrassed” (0% vs 46%) (Figure 3). The most common reason cited by patients who preferred oral pills was “I feel less embarrassed while taking pills” (46%) and “I feel less pain while taking pills” (18%).

Figure 3.

Reasons for preference for LAI vs oral antipsychotics.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable.

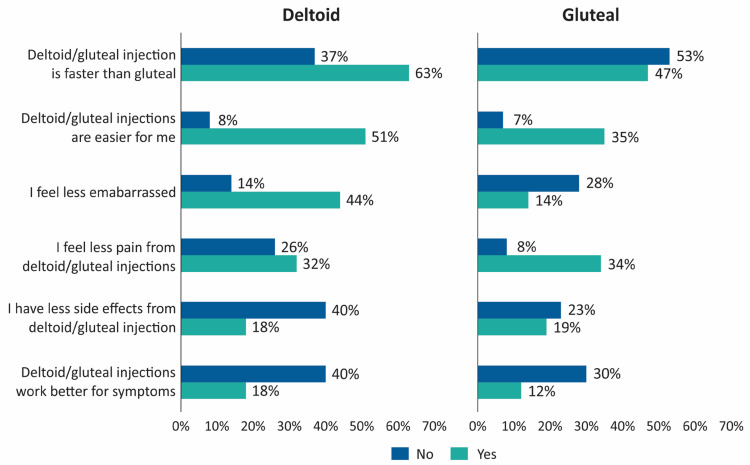

Page 3: Preference Based on Injection-Site: Deltoid vs Gluteal

The majority of patients (59%) preferred deltoid over gluteal injections and cited faster administration (63%), easier use (51%) and less embarrassing (44%) as reasons for their choice (Figure 4). Among patients who favored gluteal injections, similar reasons were cited: faster (47%), easier for me (35%) and less painful (34%).

Figure 4.

Reasons for injection-site preference: deltoid vs gluteal.

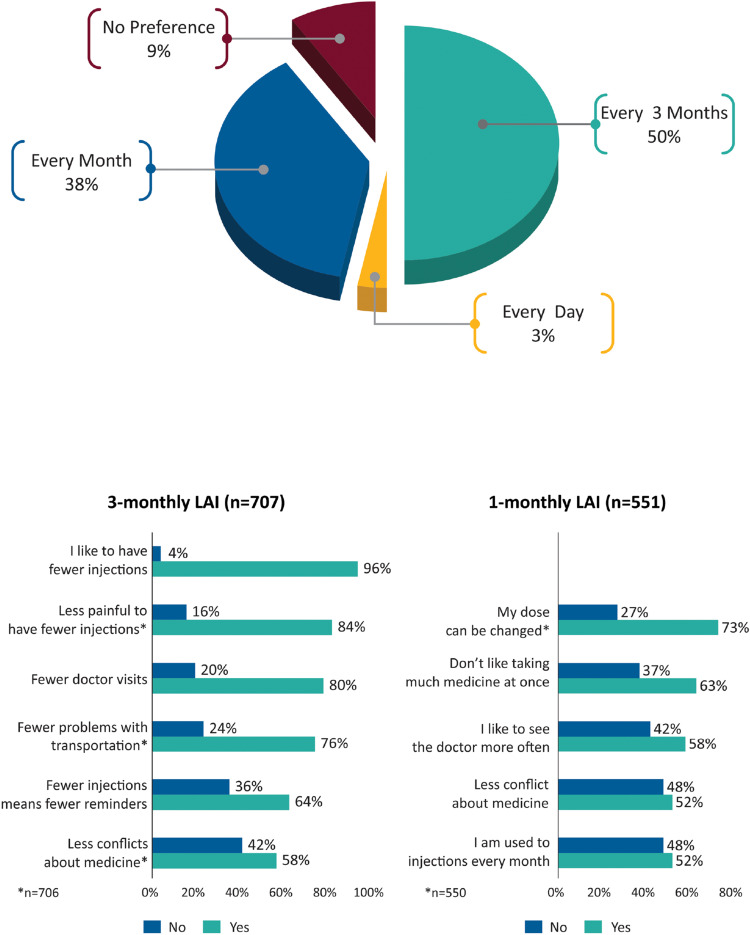

Page 4: Preference Based on Dosing Frequency: Daily vs 1-Monthly vs 3-Monthly

In total, 50% of patients preferred 3-monthly over 1-monthly (38%) or every day (3%) dosing (Figure 5). “Fewer injections” (96%), “fewer injections are less painful” (84%) and “fewer doctor visits” (80%) were the common reasons for inclination toward the 3-monthly option. Patients who preferred 1-monthly LAI cited “my dose can be changed” and “don’t like taking much medicine at once” as reasons.

Figure 5.

Medication preference based on dosing frequency and reasons for preference.

Abbreviation: LAI, long-acting injectable.

Medication Preference and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 1080 (77%) patients included in the logistic regression analysis preferred LAIs over pills (Table 1). Preference for LAI was highest among White (84.2%) followed by other racial groups (71.2%) and Black (57.7%) patients. When compared by geographic region, preference was highest in patients from Europe (88.0%) as compared with patients from the United States (59.1%), and rest of the world (70.7%). In the United States, preference for LAIs was comparable across different racial groups (Blacks, 59.6%; Whites, 58.8% and others, 57.1%). In the logistic regression analysis, race (White) and country (United States) showed a significant association (p<0.001) with patient preference for LAIs or pills, suggesting the role of culture or race in preference to LAIs/pills. The unadjusted and adjusted results (odds ratio and their statistical significance) were comparable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of Baseline Characteristics on Patients’ Medication Preference (LAI vs Pills)

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Race (White) | 2.41 (1.87; 3.12) | <0.001 | 2.39 (1.77; 3.23) | <0.001 |

| Country (USA) | 0.87 (0.81; 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.41 (0.27; 0.62) | <0.001 |

| Sex (Women) | 1.24 (0.96; 1.60) | 0.095 | 1.25 (0.92; 1.70) | 0.150 |

| Age (18–50 years) | 1.05 (0.80; 1.38) | 0.696 | 1.08 (0.73; 1.59) | 0.710 |

| BMI (normal) | 0.99 (0.77; 1.28) | 0.968 | 0.95 (0.70; 1.30) | 0.745 |

| Age of diagnosis (≤25 years) | 0.81 (0.63; 1.03) | 0.088 | 0.88 (0.65; 1.19) | 0.410 |

| Number of prior psychiatric hospitalizations (none) | 0.94 (0.72; 1.22) | 0.639 | 1.38 (0.91; 2.09) | 0.127 |

| Duration of prior hospitalizations (≤30 days) | 0.88 (0.65; 1.18) | 0.394 | 1.09 (0.71; 1.66) | 0.699 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; USA, United States of America.

Discussion

Results from this post hoc analysis of patient-reported MPQ provide insights into factors that influence a patient’s inclination for treatment with either LAI or oral antipsychotics (pills) in treatment of schizophrenia. The analysis emphasized the delineation of different segments of treatment goals that patients regard as meaningful and expect to achieve from their treatment. Overall, in this study, the attitude of patients with schizophrenia regarding LAI antipsychotics was positive.

Patient empowerment and quality-of-life-related goals were important for patients who preferred LAI antipsychotics over oral pills. The majority of interviewed patients who preferred LAIs considered general well-being, attainment of clinical goals (eg reduction in symptoms), enhanced self-sufficiency (eg better control over medications) and functional improvements (eg ability to get back to their hobbies or favorite activities) as priorities. These observations were similar to findings from a survey in people with recent-onset schizophrenia who recognized the importance of symptom alleviation and its influence on day-to-day activities and social interactions.15 Conversely, psychiatrists acknowledge symptom control, relapse prevention and magnitude of side effects as primary factors driving LAI use and often undervalue improvements in ability to work and perform chores of daily living and importance of independent living.14,17

Although healthcare professionals often consider fear of needles or injection pain as a salient barrier to LAI use, only 18% of patients in this study cited less pain as the reason for choosing oral pills over LAI antipsychotics.18,19 Embarrassment and vulnerability during administration of injections (especially gluteal) have a coercive influence on patients’ choice of mode of administration.20,21 As anticipated, embarrassment was cited as a common reason for choosing oral antipsychotics over LAIs by patient respondents in this study. Furthermore, a majority of patients preferred the less intrusive deltoid arm injections over gluteal buttock injections and cited the reasons for their preference as faster, easier and less embarrassing. This observation concurs with our previous study of PP1M in patients with schizophrenia who preferred deltoid over gluteal injections, quoting similar reasons in their responses to the MPQ.22 There were no gender differences with regard to the preference for site of administration and both men (60%) and women (57%) preferred deltoid injections. Thus, availability of LAI antipsychotics as deltoid and gluteal injections is perceived as an important advantage by patients and psychiatrists alike and is expected to enhance LAI acceptability.17,21

Extended dosing intervals of LAIs offer convenient dosing and objective monitoring of adherence.2 Infrequent doctor visits and its negative impact on the doctor-patient alliance, restrictions with dose titration, and possibility of not identifying early signs of adverse events or worsening of symptoms have been perceived as possible challenges with LAIs.23 As PP3M is the only available LAI with a 3-monthly dosing option, the MPQ included questions to gauge patient’s preference for dosing frequency.24 It was observed that given a choice, patients preferred less-frequent, quarterly injections over monthly injections and daily oral medications. Patients had a higher inclination to prefer PP3M over PP1M; fewer injections, experiencing less pain due to fewer injections and reduced doctor visits were cited as reasons driving their choice. Patients preferring PP1M considered the flexibility to change dose as an advantage over the longer dosing interval of PP3M.

Notably, this is the largest study to date where patient preference for LAIs was collected in a systematic and controlled fashion. Observations from the current analysis support the recent guideline issued by the American Psychiatric Association, which briefly mentions LAI use in the context of patient preference for LAIs, frequency of dosing and site of injection.25 It recommends the use of LAI antipsychotics in patients who prefer LAIs or who have a history of compromised adherence.25 We suggest that international guidelines should place greater emphasis on patient preference, as this ultimately will lead to greater adherence, treatment satisfaction and better treatment outcomes.

In the logistic regression analysis, among the socio-demographic factors, only race and geographic region appeared to have a significant influence suggesting the role of race and culture in patient preference. Preference for LAI was highest among Whites followed by other racial groups. When compared by geographic region, preference for LAIs was highest in Europe compared to the United States or the rest of the world. In this study, preference for LAIs was comparable between the racial groups in the United States. However, in a chart-based retrospective analysis in the United States, Whites were less likely to receive LAI antipsychotics as compared to non-Whites and Blacks.26

The current results may have potential limitations inherent to a post hoc analysis. As the analysis involved patients enrolled in a randomized study, the assessment of pragmatic viewpoint may be missing as the patients were willing to participate in the study, thereby excluding patients with poor treatment adherence.23 Additionally, the study population does not accurately represent the real-word scenario as patients at risk of suicide and those with recent substance dependence, or clinically relevant medical diagnoses were excluded.16 To provide a comprehensive perspective on patient preference, additional studies are needed that include patient populations closely representing clinical practice and real-world settings. In addition, these studies should also examine the adverse event profile and efficacy of LAI antipsychotics versus oral antipsychotics considering the pharmacokinetic differences associated with route to administration and its potential impact on tolerability and adherence.27,28 Furthermore, it has been observed that patient acceptance of LAIs improves with experience.13 Thus, as MPQ responses collected only on day 1 (before administration of PP3M and PP1M) were analyzed, patient acceptance of LAI antipsychotics would be expected to improve over time.

Conclusions

Patients who entered this study in general preferred LAIs over oral antipsychotics as a treatment choice. Patients who preferred LAI antipsychotics focused on achieving patient empowerment and quality-of-life-related goals. Additionally, patients showed a higher preference for PP3M (3-monthly LAI) than PP1M (1-monthly LAI), citing convenience and better control as reasons for their choice. Better understanding of patients’ treatment priorities and perspective could help overcome barriers to LAI use and inform the best course of personalized schizophrenia treatment for improved patient satisfaction and medication adherence. LAIs have been historically underutilized to address adherence in schizophrenia, mainly because of the perception that patients are less accepting. Our study shows that when given an option, patients are very willing to consider LAI antipsychotics. Thus, clinicians should initiate open communication with patients as well as their caregivers at the start of treatment to become more attuned to patients’ treatment preferences and foster patient-centric management. Face-to-face discussion using simple in-clinic semi-structured interviews could help gauge patients’ preferences, fears and quandaries related to route of treatment administration and educate patients about LAIs and discuss the possible risks and benefits. By addressing patients’ concerns and treatment objectives, clinicians can encourage adherence and increase the likelihood of achieving the targeted goals.

Prior Publications

Data from this post hoc analysis were presented as a poster at the Psych Congress 2019, October 03–06, San Diego, California and e-posters were presented at the Society of Biological Psychiatry (SOBP) and Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) 2020 Virtual Annual Meetings.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Janssen Research & Development, LLC. Priya Ganpathy, MPharm CMPP (SIRO Clinpharm Pvt. Ltd., India) provided writing assistance and Ellen Baum, PhD (Janssen Global Services, LLC) provided additional editorial support. The authors also thank the patients and investigators for their participation in the study.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

PS, IN, AK, AS, MM and SG are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC and hold company stocks. CB is a student at Pennsylvania State University and was working as a summer intern at Janssen Research & Development, LLC. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kane JM. Improving patient outcomes in schizophrenia: achieving remission, preventing relapse, and measuring success. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):e18. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12117tx1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Davis JM, Leucht S. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia–a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agid O, Foussias G, Remington G. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: their role in relapse prevention. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(14):2301–2317. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2010.499125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan G, Casoy J, Zummo J. Impact of long-acting injectable antipsychotics on medication adherence and clinical, functional, and economic outcomes of schizophrenia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:1171–1180. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S53795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaeger M, Rossler W. Attitudes towards long-acting depot antipsychotics: a survey of patients, relatives and psychiatrists. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1–2):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirschner M, Theodoridou A, Fusar-Poli P, Kaiser S, Jager M. Patients’ and clinicians’ attitude towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in subjects with a first episode of psychosis. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3(2):89–99. doi: 10.1177/2045125312464106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasrallah HA. The case for long-acting antipsychotic agents in the post-CATIE era. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(4):260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olayinka O, Oyelakin A, Cherukupally K, et al. Use of long-acting injectable antipsychotic in an inpatient unit of a community teaching hospital. Psychiatry J. 2019;2019:8629030. doi: 10.1155/2019/8629030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al. Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):255–264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moritz S, Hunsche A, Lincoln TM. Nonadherence to antipsychotics: the role of positive attitudes towards positive symptoms. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(11):1745–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, Kramata P, Docherty JP. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449–468. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S124658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parellada E, Bioque M. Barriers to the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the management of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(8):689–701. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0350-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heres S, Schmitz FS, Leucht S, Pajonk FG. The attitude of patients towards antipsychotic depot treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(5):275–282. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3280c28424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bridges JF, Slawik L, Schmeding A, Reimer J, Naber D, Kuhnigk O. A test of concordance between patient and psychiatrist valuations of multiple treatment goals for schizophrenia. Health Expect. 2013;16(2):164–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00704.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridges JF, Beusterien K, Heres S, et al. Quantifying the treatment goals of people recently diagnosed with schizophrenia using best-worst scaling. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:63–70. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S152870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savitz AJ, Xu H, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone palmitate 3-month formulation for patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, noninferiority study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(7):7. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geerts P, Martinez G, Schreiner A. Attitudes towards the administration of long-acting antipsychotics: a survey of physicians and nurses. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):58. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MX, Haddad PM, Chaudhry IB, McLoughlin S, Husain N, David AS. Psychiatrists’ use, knowledge and attitudes to first- and second-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections: comparisons over 5 years. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(10):1473–1482. doi: 10.1177/0269881109104882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyer S, Banks N, Roy MA, et al. A qualitative study of experiences with and perceptions regarding long-acting injectable antipsychotics: part II-physician perspectives. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(5 Suppl 1):23S–29S. doi: 10.1177/088740341305805s04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillespie M, Toner A. The safe administration of long-acting depot antipsychotics. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(8):464, 466–469. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.8.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quiroz JA, Rusch S, Thyssen A, Palumbo JM, Kushner S. Deltoid injections of risperidone long-acting injectable in patients with schizophrenia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(6):20–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hough D, Lindenmayer JP, Gopal S, et al. Safety and tolerability of deltoid and gluteal injections of paliperidone palmitate in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(6):1022–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostuzzi G, Papola D, Gastaldon C, Barbui C. New EMA report on paliperidone 3-month injections: taking clinical and policy decisions without an adequate evidence base. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(3):231–233. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016001025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daghistani N, Rey JA. Invega trinza: the first four-times-a-year, long-acting injectable antipsychotic agent. P T. 2016;41(4):222–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for The Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aggarwal NK, Rosenheck RA, Woods SW, Sernyak MJ. Race and long-acting antipsychotic prescription at a community mental health center: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):513–517. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misawa F, Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kane JM, Correll CU. Safety and tolerability of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies comparing the same antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostuzzi G, Bighelli I, So R, Furukawa TA, Barbui C. Does formulation matter? A systematic review and meta-analysis of oral versus long-acting antipsychotic studies. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]