Abstract

目的

探讨伴TP53基因异常骨髓增生异常综合征(MDS)患者的临床特征及预后。

方法

回顾性分析2009年10月至2017年12月中国医学科学院血液病医院新诊断的584例原发性MDS患者临床资料,采用包含112个血液肿瘤相关基因的靶向测序技术进行突变分析,并采用间期荧光原位杂交(FISH)技术检测TP53基因缺失。分析TP53基因突变和(或)缺失与临床特征之间的关系及其对患者总生存(OS)的影响。

结果

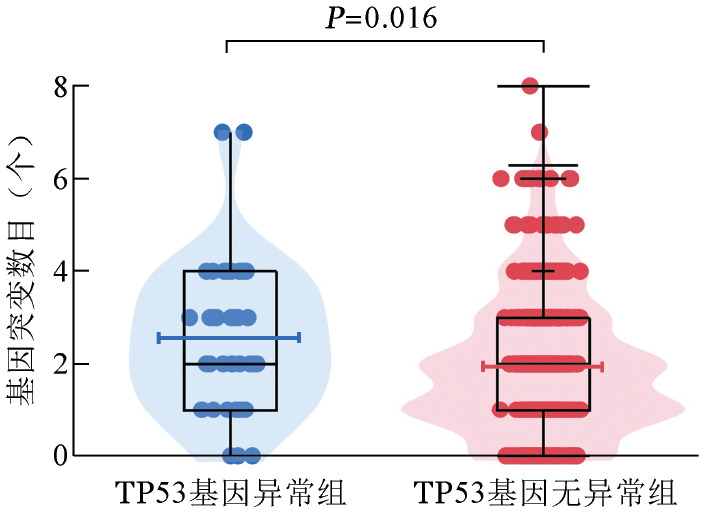

42例(7.2%)伴TP53基因异常,其中单纯基因突变31例(5.3%),单纯基因缺失8例(1.4%),同时伴有突变和缺失3例(0.5%)。34例伴TP53基因突变患者中共检测到37个TP53突变,其中35个位于DNA结合结构域(第5~8号外显子),1个位于第10号外显子,1个为剪切位点突变。伴TP53基因异常组的平均基因突变数目(2.52个)显著高于无异常组(1.96个)(z=−2.418,P=0.016)。伴TP53基因异常患者的中位年龄[60(21~78)岁]高于无异常患者[52(14~83)岁](z=−2.188,P=0.029);伴TP53基因异常组中复杂核型比例、IPSS较高危组(中危-2及高危)比例显著高于无异常组(P值均<0.001)。伴TP53基因异常组的中位OS期[13(95%CI 7.57~18.43)个月]较无异常组(未达到)显著缩短(χ2=12.342,P<0.001),但多因素模型纳入复杂核型进行校正后,TP53突变不再是独立预后因素。

结论

伴TP53基因异常MDS患者中基因突变较基因缺失常见,突变位点主要分布于DNA结合结构域。TP53基因异常与复杂核型相关,且常与多个基因突变相伴出现。在多因素模型纳入复杂核型校正后,TP53基因异常则不再是独立的预后因素。

Keywords: 骨髓增生异常综合征, TP53基因, 突变, 缺失, 预后

Abstract

Objective

To explore the clinical implications and prognostic value of TP53 gene mutation and deletion in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Methods

112-gene targeted sequencing and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were used to detect TP53 mutation and deletion in 584 patients with newly diagnosed primary MDS who were admitted from October 2009 to December 2017. The association of TP53 mutation and deletion with several clinical features and their prognostic significance were analyzed.

Results

Alterations in TP53 were found in 42 (7.2%) cases. Of these, 31 (5.3%) cases showed TP53 mutation only, 8 (1.4%) cases in TP53 deletion only, 3 (0.5%) cases harboring both mutation and deletion. A total of 37 mutations were detected in 34 patients, most of them (94.6%) were located in the DNA binding domain (exon5–8), the remaining 2 were located in exon 10 and splice site respectively. Patients with TP53 alterations harbored significantly more mutations than whom without alterations (z=−2.418, P=0.016). The median age of patients with TP53 alterations was higher than their counterparts[60 (21–78) years old vs 52 (14–83) years old, z=−2.188, P=0.029]. TP53 alterations correlated with complex karyotype and International prognostic scoring system intermediate-2/high significantly (P<0.001). Median overall survival of patients with TP53 alterations was shorter than the others[13 (95%CI 7.57–18.43) months vs not reached, χ2=12.342, P<0.001], while the significance was lost during complex karyotype adjusted analysis in multivariable model.

Conclusion

TP53 mutation was more common than deletion in MDS patients. The majority of mutations were located in the DNA binding domain. TP53 alterations were strongly associated with complex karyotype and always coexisted with other gene mutations. TP53 alteration was no longer an independent prognostic factor when complex karyotype were occurred in MDS.

Keywords: Myelodysplastic syndromes, TP53 gene, Mutation, Deletion, Prognosis

近年来,全基因组和靶向测序技术的临床应用揭示了多种基因在骨髓增生异常综合征(MDS)的发生及转归中发挥着重要作用[1]–[5]。已有研究证实尽管TP53突变和(或)缺失在MDS患者中的发生率较低,但却具有重要的预后判断价值[1],[3],[6]–[8]。我们应用靶向测序技术和间期荧光原位杂交(FISH)技术检测了584例新诊断的原发性MDS患者TP53基因突变及缺失情况,并分析了伴TP53基因异常MDS患者的临床特征及其预后意义,现报道如下。

病例与方法

1.病例资料:2009年10月至2017年12月于中国医学科学院血液病医院MDS和骨髓增殖性肿瘤(MPN)诊疗中心确诊并保存骨髓细胞标本的584例初诊MDS患者纳入本研究。男368例,女216例,中位年龄53(14~83)岁。按照WHO(2016)标准[9]进行诊断和分型,其中MDS伴单系发育异常(MDS-SLD)25例(4.3%),MDS伴多系发育异常(MDS-MLD)304例(52.1%),MDS伴环形铁粒幼红细胞(MDS-RS)21例(3.6%),MDS伴原始细胞增多-1(MDS-EB-1)106例(18.2%),MDS伴原始细胞增多-2(MDS-EB-2)111例(19.0%),MDS伴单纯5q− 7例(1.2%),MDS未分类(MDS-U)10例(1.7%)。采用国际预后积分系统(IPSS)[10]对患者进行预后分层,其中低危组53例(10.2%),中危-1组313例(60.4%),中危-2组123例(23.7%),高危组29例(5.6%)。584例患者中可追踪到治疗方案的共504例,48例(9.5%)接受单纯支持治疗,289例(57.3%)接受免疫抑制剂或免疫调节剂治疗,73例(14.5%)接受地西他滨治疗,58例(11.5%)接受造血干细胞移植,14例(2.8%)接受CAG/HAG(阿克拉霉素/高三尖杉酯碱+阿糖胞苷+G-CSF)方案化疗,22例(4.4%)单纯接受中医药治疗。

2.染色体核型分析:骨髓细胞经过24 h培养,收集细胞常规制片,R显带,根据《人类细胞遗传学国际命名体制(ISCN2013)》[11]描述核型异常。染色体核型可分析共518例(88.7%)。按照IPSS染色体核型分组标准[10]进行染色体核型预后分组。

3.间期FISH检测TP53缺失:采用VYSIS双色标记TP53探针,TP53(17p13)基因标记为红色(R),CEP17(17p11-q11)基因标记为绿色(G),应用间期FISH技术进行检测,正常信号特征为2R2G,阳性信号特征为2G1R,−17为1R1G。荧光显微镜下每样本至少观察500个间期细胞。TP53基因缺失[del(17p13)]阳性阈值为2.89%。

4.靶向二代测序分析:取患者骨髓,分离单个核细胞,常规提取DNA。使用PCR引物扩增目的基因组(涵盖112个血液肿瘤相关基因),将目标区域DNA富集后,采用Ion Torrent半导体测序平台进行测序。平均基因覆盖率98.1%,平均测序深度1 314×。测序后原始数据利用CCDS、人类基因组数据库(HG19)、dbSNP(v138)、1000 genomes、COSMIC、PolyPhen-2等数据库进行生物信息学分析,筛选致病性基因突变位点。具体方法参见本研究组此前已发表文献[5]。

5.随访:所有病例随访至2018年7月31日,随访资料来源于住院病例、门诊病例及电话随访记录。对随访期间死亡的病例,根据病例记录或与患者家属电话联系确认。中位随访时间为13(1~132)个月,其中2个月内失访患者65例(11.1%),不纳入生存分析。余519例患者进行生存分析,总生存(OS)期指自诊断日期到死亡或末次随访日期。

6.统计学处理:全部统计分析均利用SPSS 25.0统计软件完成。非正态分布的计量资料采用Mann-Whitney U检验,数据以中位数(范围)表示;分类资料采用卡方检验或Fisher精确概率法进行差异性分析;Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线,单因素分析采用Log-rank检验,多因素分析采用Cox回归分析。双侧检验P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果

1. TP53基因异常检出率:584例MDS患者中共42例(7.2%)伴有TP53基因突变和(或)缺失,其中基因突变34例(5.8%)(31例为单纯突变),基因缺失11例(1.9%)(8例为单纯缺失),同时有基因突变和缺失3例(0.5%)。

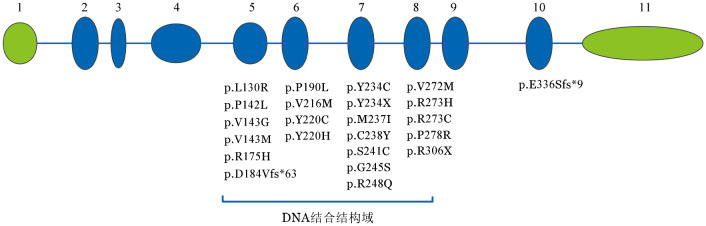

2. TP53基因突变位点分布及共突变情况:34例伴有基因突变的患者中共检测到37个TP53突变,其中31例有1个突变,3例各有2个突变。30个为错义突变,4个为无义突变,移码(缺失)突变和剪接位点突变分别有2个和1个。共35个(94.6%)突变位于DNA结合结构域(第5~8号外显子),出现频率较高的突变位点分别有密码子175(3个)、220(6个)、248(4个)、273(4个)和306(3个)。其他突变位点详见图1。

图1. 34例骨髓增生异常综合征患者TP53基因突变位点分布及相应的氨基酸改变.

1~11分别为第1~11号外显子,绿色示非编码外显子,蓝色示编码外显子

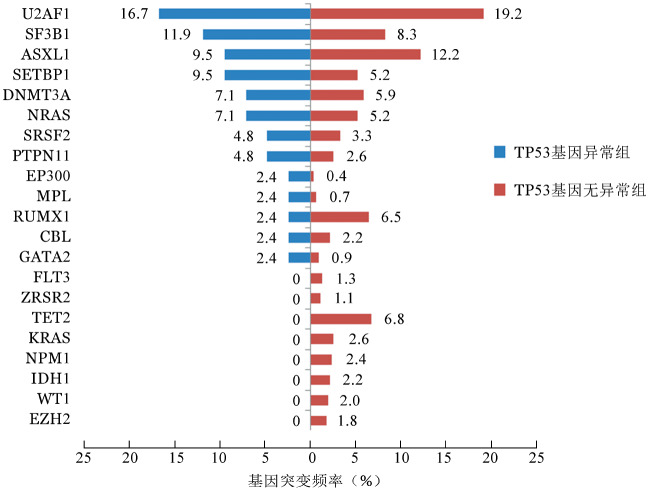

伴有TP53基因异常组患者的平均突变数目为2.52个,显著高于无异常组患者(1.96个),差异有统计学意义(z=−2.418,P=0.016)(图2)。二代测序结果表明,全部584例患者中常见的基因突变有U2AF1(19.0%)、ASXL1(12.0%)、SF3B1(8.6%)、TET2(6.3%)、RUNX1(6.2%)、DNMT3A(6.0%)、SETBP1(5.5%)和NRAS(5.3%)。在伴有TP53基因异常的患者中发生频率较高的突变分别为U2AF1(16.7%)、SF3B1(11.9%)、ASXL1(9.5%)、SETBP1(9.5%)、DNMT3A(7.1%)、NRAS(7.1%)、SRSF2(4.8%)和PTPN11(4.8%)。不同组别的基因突变频率详见图3。

图2. TP53基因异常组(42例)和无异常组(542例)骨髓增生异常综合征患者的基因突变数目比较.

图3. TP53基因异常组(42例)和无异常组(542例)骨髓增生异常综合征患者其他共同发生的基因突变频率.

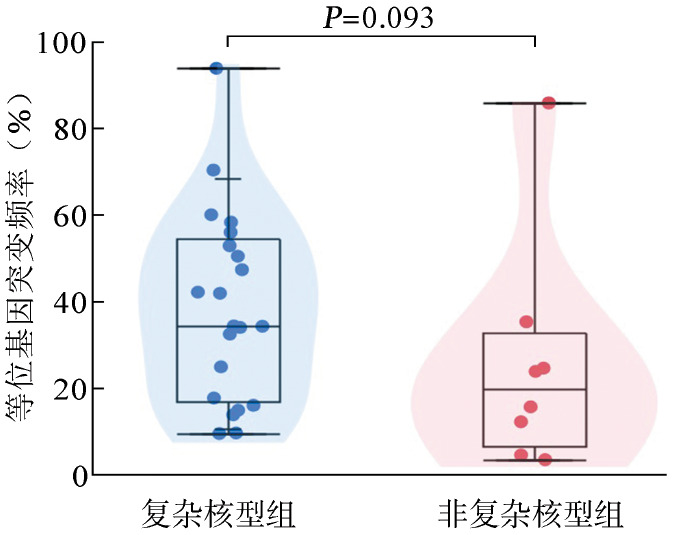

3.伴TP53异常患者的临床特征:伴有TP53基因异常组患者的中位年龄为60(21~78)岁,较无异常组患者[52(14~83)岁]显著升高,差异有统计学意义(z=−2.188,P=0.029)。TP53基因异常组与无异常组相比,其性别、WHO诊断分型、初诊外周血血红蛋白水平、白细胞计数、中性粒细胞计数、血小板计数、骨髓原始细胞比例差异均无统计学意义(P值均>0.05)。伴有TP53基因异常组中复杂核型的比例显著高于无异常组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.001);伴复杂核型患者的中位等位基因突变频率(VAF)为34.37(9.47~93.90),非复杂核型为19.75(3.45~85.91)(z=−1.708,P=0.093)(图4)。按照IPSS对患者进行预后分组评估,伴有TP53基因异常组中IPSS较高危组(中危-2及高危组)所占的比例显著高于无异常组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.001)。TP53基因异常与无异常组患者各临床特征之间的比较见表1。

图4. 复杂核型(21例)与非复杂核型(8例)分组骨髓增生异常综合征患者的等位基因突变频率.

表1. TP53基因异常组与无异常组骨髓增生异常综合征(MDS)患者临床特征比较.

| 临床特征 | TP53基因异常组(42例) | 无异常组(542例) | 统计量 | P值 |

| 性别[例(%)] | 0.507 | |||

| 男 | 29(69.0) | 339(62.5) | ||

| 女 | 13(31.0) | 203(37.5) | ||

| 年龄[岁,M(范围)] | 60(21~78) | 52(14~83) | -2.188 | 0.029 |

| WHO 2016诊断分型[例(%)] | 10.422 | 0.166 | ||

| MDS-SLD | 0(0) | 25(4.6) | ||

| MDS-MLD | 20(47.6) | 284(52.4) | ||

| MDS-RS | 1(2.4) | 20(3.7) | ||

| MDS-EB-1 | 13(31.0) | 93(17.2) | ||

| MDS-EB-2 | 7(16.7) | 104(19.2) | ||

| 5q− | 1(2.4) | 6(1.1) | ||

| MDS-U | 0(0) | 10(1.8) | ||

| HGB[g/L,M(范围)] | 70(47~119) | 74(28~153) | 1.351 | 0.177 |

| WBC[×109/L,M(范围)] | 2.48(0.84~12.39) | 2.86(0.61~20.68) | 1.334 | 0.182 |

| ANC[×109/L,M(范围)] | 1.12(0~9.14) | 1.20(0~11.17) | 0.769 | 0.442 |

| PLT[×109/L,M(范围)] | 43.5(4~1 100) | 61(2~1 232) | 1.706 | 0.088 |

| 原始细胞比例[%,M(范围)] | 3(0~18) | 2.5(0~19.5) | -0.540 | 0.589 |

| 染色体核型[例(%)] | <0.001 | |||

| 复杂核型 | 26(70.3) | 48(10.0) | ||

| 非复杂核型 | 11(29.7) | 433(90.0) | ||

| IPSS预后分组(4组)[例(%)] | 44.651 | <0.001 | ||

| 低危 | 0(0) | 53(11.0) | ||

| 中危-1 | 8(21.6) | 305(63.4) | ||

| 中危-2 | 25(67.6) | 98(20.4) | ||

| 高危 | 4(10.8) | 25(5.2) | ||

| IPSS预后分组(2组)[例(%)] | <0.001 | |||

| 较低危(低危及中危-1) | 8(21.6) | 358(74.4) | ||

| 较高危(中危-2及高危) | 29(78.4) | 123(25.6) |

注:MDS-SLD:MDS伴单系发育异常;MDS-MLD:MDS伴多系发育异常;MDS-RS:MDS伴环形铁粒幼红细胞;MDS-EB-1:MDS伴原始细胞增多-1;MDS-EB-2:MDS伴原始细胞增多-2;5q−:MDS伴单纯5q−;MDS-U:MDS未分类;ANC:中性粒细胞绝对值;IPSS:国际预后积分系统

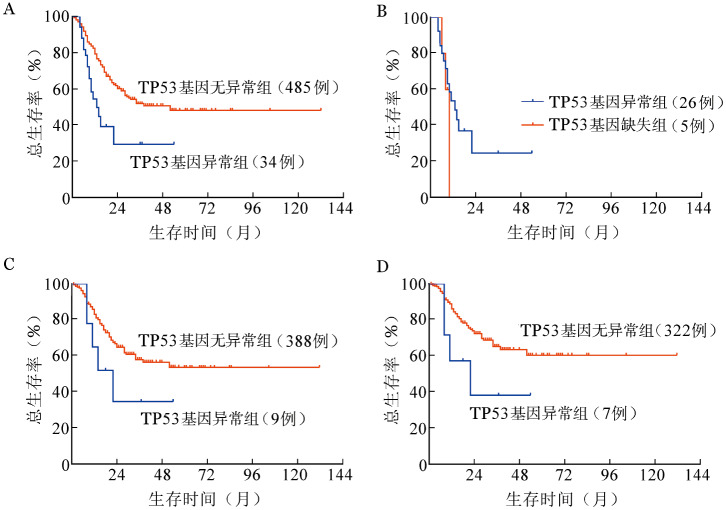

4. TP53异常的预后分析:截止末次随访日,死亡162例(31.2%),伴有TP53基因异常组死亡18例(52.9%),无异常组死亡144例(29.7%)。伴有TP53基因异常组患者的中位OS期为13(95%CI 7.57~18.43)个月,无异常组患者中位OS期未达到。伴有TP53基因异常组患者的生存期较无异常组显著缩短(图5A),差异有统计学意义(χ2=12.342,P<0.001)。伴TP53突变组及缺失组中位OS期分别为13(95%CI 7.68~18.33)个月、10个月,差异无统计学意义(χ2=0.687,P=0.407)(图5B)。

图5. 骨髓增生异常综合征患者生存曲线.

A:伴与不伴TP53基因异常组比较;B:TP53基因突变组及基因缺失组比较;C:非复杂核型患者中伴与不伴TP53基因异常组比较;D:国际预后积分系统较低危组(低危及中危-1)患者中伴与不伴TP53基因异常组比较

对突变频率大于2%的基因分别进行Log-rank检验,除TP53基因异常外,还有U2AF1、ASXL1、TET2、NRAS和PTPN11基因突变与更短的OS期显著相关(P<0.05)(表2)。将P<0.1的基因以及年龄(按照<50岁、≥50岁分组)纳入Cox回归分析模型,结果表明TP53基因异常为OS的独立预后不良因素(HR=2.248,95% CI 1.363~3.709,P=0.002)。而在纳入复杂核型进行校正之后,TP53异常对OS的影响失去显著性(P=0.913)(表2)。

表2. 影响伴TP53基因异常骨髓增生异常综合征患者总生存的单因素和多因素分析.

| 变量 | HR | 95%CI | P值 |

| 单因素分析 | |||

| TP53异常 | 2.321 | 1.153~4.670 | <0.001 |

| U2AF1突变 | 1.540 | 1.066~2.227 | 0.022 |

| ASXL1突变 | 1.650 | 1.083~2.515 | 0.020 |

| TET2突变 | 1.780 | 1.090~2.909 | 0.021 |

| RUNX1突变 | 1.685 | 0.934~3.041 | 0.083 |

| SETBP1突变 | 1.643 | 0.931~2.899 | 0.086 |

| NRAS突变 | 1.901 | 1.098~3.291 | 0.022 |

| PTPN11突变 | 2.716 | 1.379~5.349 | 0.004 |

| 年龄≥50岁 | 2.610 | 1.819~3.744 | <0.001 |

| 复杂核型 | 3.706 | 2.469~5.561 | <0.001 |

| 无年龄及核型校正的多因素分析 | |||

| TP53异常 | 2.607 | 1.582~4.296 | <0.001 |

| U2AF1突变 | 1.505 | 1.035~2.189 | 0.032 |

| ASXL1突变 | 1.569 | 1.022~2.410 | 0.039 |

| TET2突变 | 2.054 | 1.247~3.383 | 0.005 |

| RUNX1突变 | 1.870 | 1.027~3.406 | 0.041 |

| NRAS突变 | 1.794 | 1.034~3.111 | 0.038 |

| 年龄校正的多因素分析 | |||

| TP53异常 | 2.248 | 1.363~3.709 | 0.002 |

| U2AF1突变 | 1.720 | 1.178~2.512 | 0.005 |

| TET2突变 | 1.863 | 1.129~3.075 | 0.015 |

| PTPN11突变 | 2.191 | 1.054~4.554 | 0.036 |

| 年龄≥50岁 | 2.544 | 1.765~3.668 | <0.001 |

| 年龄及核型校正的多因素分析 | |||

| U2AF1突变 | 1.972 | 1.289~3.017 | 0.002 |

| TET2突变 | 1.737 | 1.006~2.998 | 0.047 |

| RUNX1突变 | 2.155 | 1.143~4.062 | 0.018 |

| SETBP1突变 | 2.086 | 1.026~4.241 | 0.042 |

| 年龄≥50岁 | 2.962 | 1.969~4.458 | <0.001 |

| 复杂核型 | 3.938 | 2.581~6.010 | <0.001 |

对染色体核型可分析的518例患者进行分组,复杂核型组中,是否伴有TP53基因异常对OS期无影响;非复杂核型组中,伴TP53基因异常的患者死亡5例(55.6%),中位OS期为22(95%CI 8.921~35.079)个月,无基因异常患者死亡100例(25.8%),中位OS未达到,两者之间差异无统计学意义(χ2=2.192,P=0.139)(图5C)。进一步按照IPSS预后分组,IPSS较高危组(中危-2及高危)中,TP53基因异常组与无异常组之间OS期无显著差异;IPSS较低危组(低危及中危-1)中,TP53基因异常患者的中位OS期[22(95%CI 0~44.563)个月]较无异常患者(中位OS期未达到)有降低的趋势(χ2=2.744,P=0.098)(图5D)。

讨论

人类TP53基因位于17号染色体短臂,其编码的p53蛋白通过DNA损伤修复、细胞周期调控、诱导凋亡等多种途径发挥着重要的肿瘤抑制作用[12]。在所有人类肿瘤中,TP53基因突变率高达50%[13]。相比于实体肿瘤的高突变率,TP53突变在血液系统肿瘤中的发生率较低,迄今报道的原发性MDS中TP53基因的突变率为5%~10%[2]–[3],[14]。在一项针对TP53基因突变和缺失的研究[15]中,TP53基因异常在MDS中的总发生率为7%,单纯突变5%,单纯缺失1%,同时伴有突变和缺失占1%。本研究中,TP53基因异常的总发生率为7.2%,单纯突变5.3%,单纯缺失1.4%,同时伴突变和缺失占0.5%,与文献报道基本一致。

TP53突变在MDS中好发于DNA结合结构域[7],[12],[16],以错义突变最为常见[7],本研究结果与文献报道基本一致。有关MDS中常见突变位点的报道较少,本研究中较多见的突变位点有密码子175、220、248、273、306。本研究我们未发现TP53异常与其他基因的相关性,可能与队列中TP53异常的发生率较低有关。

研究表明,TP53基因突变在老年急性髓系白血病(AML)及MDS患者中较年轻患者常见[15],[17]–[18],此外一些大宗病例研究在年龄相关的克隆性造血中也发现了TP53突变,且与血液肿瘤的发生和不良预后相关[19]–[20]。本研究结果表明伴TP53基因异常的患者的中位年龄显著高于无异常患者,与目前公认的TP53基因突变随年龄增大突变频率增高的观点一致。

在MDS中TP53突变与复杂核型、单纯5q−、IPSS较高危分组及不良预后相关[7]–[8],[21]–[22]。Sallman等[8]的研究表明TP53突变频率增高与复杂核型比例增高相关,且VAF>40%为一独立的预后不良因素。本研究中,伴有TP53异常组中复杂核型、IPSS较高危组的比例较无异常组显著增高,伴复杂核型患者的TP53突变频率较非复杂核型患者有增高的趋势,与既往结论一致。本研究我们未发现TP53突变与单纯5q−的相关性,可能与本队列中单纯5q−的病例较少相关,有待扩大样本量后进一步分析。

近年来,国外多个中心的研究表明,TP53基因突变在MDS中为独立的预后不良因素[1],[6]–[7],[23],Stengel等[15]的研究说明TP53基因突变和缺失在MDS中均导致更差的OS。本研究中TP53基因突变组和缺失组的OS期无显著差异,TP53基因异常在单因素及纳入基因突变、年龄的多因素分析中为独立的预后不良因素,而在纳入复杂核型校正后,TP53基因异常则不再为独立的预后不良因素。这与Volkert等[24]、Tefferi等[25]及Xu等[26]的结论一致。本研究的结果说明,在复杂核型及IPSS较高危组中TP53基因异常对OS无明显影响,而在非复杂核型及IPSS较低危组中,TP53基因异常患者OS期有更短的趋势,这与Tefferi等[25]的报道相近,可能提示对于伴有TP53基因异常的MDS较低危组患者可采用更加积极的治疗手段,如去甲基化治疗等。我们考虑非复杂核型及IPSS较低危组中TP53基因异常的病例数较少,可能导致其对OS的影响差异不显著,有待扩大病例数后进一步证实。

综上所述,我们的研究显示TP53基因异常在MDS中的发生率较低,发生率随着年龄的增大而升高。基因突变较缺失常见,突变高发于DNA结合结构域。TP53基因异常与复杂核型、IPSS较高危组高度相关,且常与其他基因突变相伴出现。其对预后的不良影响主要与复杂核型相关,可能在低危MDS患者中有一定提示预后的价值。

Funding Statement

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(81870104、81530008、81470297、81770129);天津市自然科学基金重点项目(18JCZDJC34900);中国医学科学院医学与健康科技创新工程(2016-I2M-1-001);协和学者与创新团队发展计划

Fund program: National Natural Science Foundation of China(81870104, 81530008, 81470297, 81770129); Tianjin Key Natural Science Funds(18JCZDJC34900); CAMS Initiative Fund for Medical Sciences(2016-I2M-1-001); Program for Peking Union Scholars and Innovative Research Team

References

- 1.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes[J] N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Malcovati L, et al. Clinical and biological implications of driver mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Blood. 2013;122(22):3616–3627, 3699. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-518886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Leukemia. 2014;28(2):241–247. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Della PMG, Gallì A, Bacigalupo A, et al. Clinical effects of driver somatic mutations on the outcomes of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes treated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation[J] J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(30):3627–3637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.李 冰, 王 静雅, 刘 晋琴, et al. 靶向测序检测511例骨髓增生异常综合征患者基因突变[J] 中华血液学杂志. 2017;38(12):1012–1016. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazha A, Narkhede M, Radivoyevitch T, et al. Incorporation of molecular data into the Revised International Prognostic Scoring System in treated patients with myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Leukemia. 2016;30(11):2214–2220. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulasekararaj AG, Smith AE, Mian SA, et al. TP53 mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome are strongly correlated with aberrations of chromosome 5, and correlate with adverse prognosis[J] Br J Haematol. 2013;160(5):660–672. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sallman DA, Komrokji R, Vaupel C, et al. Impact of TP53 mutation variant allele frequency on phenotype and outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Leukemia. 2016;30(3):666–673. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia[J] Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg P, Cox C, Lebeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Blood. 1997;89(6):2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaffer LG, McGowan-Jordan J, Schmid M, et al. An intemational system for human cytogenetic nomenclature (2013)[M] Basel: ISCN; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Mcgraw KL, Sallman DA, et al. The role of p53 in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia: molecular aspects and clinical implications[J] Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(8):1777–1790. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1266625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivlin N, Brosh R, Oren M, et al. Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene: important milestones at the various steps of tumorigenesis[J] Genes Cancer. 2011;2(4):466–474. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cazzola M, Della PMG, Malcovati L. The genetic basis of myelodysplasia and its clinical relevance[J] Blood. 2013;122(25):4021–4034. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-381665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stengel A, Kern W, Haferlach T, et al. The impact of TP53 mutations and TP53 deletions on survival varies between AML, ALL, MDS and CLL: an analysis of 3307 cases[J] Leukemia. 2017;31(3):705–711. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang W, Routbort MJ, Tang Z, et al. Characterization of TP53 mutations in low-grade myelodysplastic syndromes and myelodysplastic syndromes with a non-complex karyotype[J] Eur J Haematol. 2017;99(6):536–543. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva P, Neumann M, Schroeder MP, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly is characterized by a distinct genetic and epigenetic landscape[J] Leukemia. 2017;31(7):1640–1644. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Liu J, Jia Y, et al. Clinical features and biological implications of different U2AF1 mutation types in myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2018;57(2):80–88. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies[J] Nat Med. 2014;20(12):1472–1478. doi: 10.1038/nm.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes[J] N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belickova M, Vesela J, Jonasova A, et al. TP53 mutation variant allele frequency is a potential predictor for clinical outcome of patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Oncotarget. 2016;7(24):36266–36279. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bally C, Ades L, Renneville A, et al. Prognostic value of TP53 gene mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia treated with azacitidine[J] Leuk Res. 2014;38(7):751–755. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi K, Patel K, Bueso-Ramos C, et al. Clinical implications of TP53 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes treated with hypomethylating agents[J] Oncotarget. 2016;7(12):14172–14187. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volkert S, Kohlmann A, Schnittger S, et al. Association of the type of 5q loss with complex karyotype, clonal evolution, TP53 mutation status, and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome[J] Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53(5):402–410. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tefferi A, Lasho TL, Patnaik MM, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing in myelodysplastic syndromes and prognostic interaction between mutations and IPSS-R[J] Am J Hematol. 2017;92(12):1311–1317. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu F, Wu LY, He Q, et al. Exploration of the role of gene mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes through a sequencing design involving a small number of target genes[J] Sci Rep. 2017;7:43113. doi: 10.1038/srep43113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]