Abstract

Introduction

The National Health Service (NHS) Long-Term Plan (2019) acknowledges that children and young people with suspected autism wait too long for diagnostic assessment and sets out to reduce waiting times. However, diagnostic pathways vary with limited evidence on what model works best, for whom and in what circumstances. The National Autism Plan for Children (2003) recommended that assessment should be completed within 13 weeks but referral to diagnosis can take as long as 799 days.

This Rapid Realist Review (RRR) is the first work package in a national programme of research: a Realist Evaluation of Autism ServiCe Delivery (RE-ASCeD). We explore how particular approaches may deliver high-quality and timely autism diagnostic services for children with possible autism; high quality is defined as compliant with National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence (2011) guidelines, and timely as a pathway lasting no more than one calendar year, based on previous work.

Methods and analysis

RRR is a well-established approach to synthesising evidence within a compressed timeframe to identify models of service delivery leading to desired outcomes. RRR works backwards from intended outcomes, identified by NICE guidelines and the NHS England Long-Term Plan. The focus is a clearly defined intervention (the diagnostic pathway), associated with specific outcomes (high quality and timely), within a particular set of parameters (Autism and Child & Adolescent Mental Health services in the UK). Our Expert Stakeholder Group consists of policymakers, content experts and knowledge users with a wide range of experience to supplement, tailor and expedite the process. The RRR is consistent with Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) and includes identifying the research question, searching for information, quality appraisal, data extraction, synthesising the evidence, validation of findings with experts and dissemination.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval not required. Findings will inform the wider RE-ASCeD evaluation and be reported to NHS England.

Trial registration number

NCT04422483. This protocol relates to Pre-results.

Keywords: developmental neurology & neurodisability, primary care, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This will be the first rapid realist review to synthesise evidence on the diagnostic pathway for children and adolescents with possible autism.

The review will address a major knowledge gap, using an established method, to explore how particular approaches may deliver high-quality and timely autism diagnostic services for children with possible autism.

The quality and relevance of the findings will be strengthened with the input of our Expert Stakeholder Group.

Introduction

The recently published NHS Long-Term Plan1 acknowledges that children and young people with suspected autism wait too long for diagnostic assessment. The Plan set out an ambitious strategy to reduce waiting times while supporting children with autism (or other neurodevelopmental disorders) and their families, throughout the diagnostic process. However, there is much variation in the diagnostic pathway and limited evidence on what model works best, for whom and in what circumstances.

Autism, also called autistic spectrum disorder or condition, affects around 1%–2% of children.2–5 It is characterised by the presence of ‘persistent deficits in the ability to initiate and sustain reciprocal social interaction and social communication, and by a range of restricted, repetitive, inflexible patterns of behaviour and interests.6 7 Presentation varies significantly in relation to severity of these deficits, intellectual ability or disability and language skills.6 7 Co-occurring mental health conditions are common,1 and children with autism, whether with associated learning difficulties or not, contribute significantly to inpatient Tier 4 Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), particularly in girls without learning disability, often only receiving a diagnosis once in that setting.8

People with autism are often dependent on adult support and/or care throughout their lives. The costs associated with autism include financial costs to families and education, supportive living accommodation and individual productivity loss.9 The impact of autism and behavioural difficulties on families is great, with parents of children with autism experiencing higher levels of stress than parents of children with other disabilities.10

Services for children and young people with autism are under increasing pressure to deliver timely diagnostic assessment. The National Autism Plan for Children in 2003,11 recommended that the first professional contact with parents following referral to Child Development Services (CDCs) or CAMHS should be within 6 weeks of referral, and that the assessment process should be completed within 13 weeks. However, journey times from referral to diagnosis as long as 799 days have been reported,12–14 and a recent service review highlighted the frustration of families, ‘sometimes isolated, with little or no support’.13 This suggests demand for diagnostic services has outstripped capacity, exacerbated by recent increases in demand.15 Additionally, assessment is time consuming and costly; Galliver et al,16 found assessments took a mean of 13 hours of professional time, costing £800 per child/young person. Our recent study of 500 children’s diagnostic journeys estimated 15 hours, costing around £950 per child.14

Beyond the issues of capacity, there are several factors relating to the child, their family or the professionals involved which contribute to the time taken in reaching a diagnosis.14 Brett et al,17 identified the importance of case complexity, with the presence of additional neurodevelopmental diagnoses such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),18 delaying diagnosis. The longest journey times reflect either complexity, adoption of a ‘wait and see’ approach, or family issues such as poor clinic attendance.19 Other family factors including socioeconomic status and the presence of a pre-existing sibling with autism in the family may reduce time to diagnosis.17

There is wide variation between services in the pathway to diagnosis. UK NHS diagnostic practice is based on National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,20 widely acknowledged as a gold standard internationally. Diagnosis requires assessment of the child in more than one setting, for example home, school and clinic. NICE20 recommends using a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach with representation from child health and mental health services, with a core team of a paediatrician and/or child and adolescent psychiatrist, speech therapist and psychologist. Assessment should consider a range of explanations for individual signs and symptoms, including other neurodevelopmental disorders, mental health and behavioural disorders.20 To achieve this is labour intensive and often costly,21 but identifies essential areas of health and support needs for the child and family.

Several services have already adapted their pathways in an attempt to become timelier and more efficient. Approaches include single practitioner or abbreviated assessments,15 22 23 both reducing the hours of professional time involved,23 the use of skill mix, for example replacing expensive doctor time with a nurse or allied health professional specialist role; training programmes to increase the expertise and competencies of team members and referrers; and improving information gathering either prior to accepting the referral,15 or through the use of digital technologies.24 However, the MDT approach remains the gold standard and is necessary in most cases to manage diagnostic complexity, and to create a complete picture of the child/young person’s strengths and needs.20 There are also examples of services that have benefited from overall structural reorganisation, for example by integration of CDCs and CAMHS,25 joining diagnostic services together15 and improving data collection.15 Integrating diagnostic services for autism and ADHD, which frequently co-occur, could possibly improve efficiency by avoiding children going through separate but very similar diagnostic processes for each possible condition.25

Families frequently report negative experiences of the journey through the diagnostic assessment process, alongside lack of signposting and access to support and therapeutic intervention postdiagnosis.26 27 Crane et al’s,26 survey of 1047 families who had been through an autism diagnostic process in the UK, found over 50% were dissatisfied with the process. Predictors for low satisfaction included time taken to diagnosis, quality of information given, stress associated with the diagnostic process and quality of support offered postdiagnosis.

The need to improve the diagnostic process and support for families for children with possible autism has been widely acknowledged.1 15 26 27 However, there is a significant evidence gap concerning how best to deliver effective and efficient diagnostic pathways for children and young people with possible autism in a timely manner and how to deliver appropriate support to families throughout the diagnostic process. This paper represents the protocol for a 7 month rapid realist review (RRR), as part of the Realist Evaluation of Autism ServiCe Delivery (RE-ASCeD) research programme, commencing January 2020 and intending to fill this evidence gap.

Aims and objectives

Given that some local providers have already reconfigured their services in an attempt to address these issues,15 28 this RRR is the first step in a national RE-ASCeD. This review aims to explore how particular approaches may deliver high-quality and timely autism diagnostic services for children with possible autism; high quality is defined as compliant with NICE (2011) guidelines,20 and timely is defined as a pathway lasting no more than one calendar year, based on previous work (paper in preparation). Research questions for the RRR are as follows:

How do various models of autism diagnostic and support services address the differing needs of different service user groups and what contexts and mechanisms affect their ability to do so?

How do models of autism diagnostic and support services improve service user diagnostic experience?

What aspects of implementation, staffing and organisational context influence how models of autism diagnostic and support services operate?

Methods and analysis

In line with a realist approach, we will conduct an RRR to build on the systematic review undertaken in preparation for the NICE guidelines.20 The RRR will add to this through providing context-specific explanations for what works within a particular set of parameters.29 RRR is a well-established approach to synthesising evidence within a compressed time period that can identify groups of interventions or models of service delivery that relate to desired outcomes.29 In using an RRR approach, we will work backwards from the intended outcomes as identified by NICE guidelines,20 and the NHS England Long-Term Plan.1 The key steps are consistent with the RAMESES standards,30 for realist syntheses and include identifying the research question, searching for information, quality appraisal, data extraction, synthesising the evidence, validation of findings with content experts and dissemination.29 31

What differentiates RRR from a full realist review is arguable but RRR is explicitly designed to engage those with expertise in order to accelerate the search process and validate findings.29 The wider RE-ASCeD project team have significant expertise in realist evaluation, paediatric neurodisability and autism and their contribution to each stage is outlined below. The Expert Stakeholder Group consists of content experts, knowledge users and policymakers with a wide range of experience, including consultant paediatrician, speech and language therapy, child psychology, occupational therapy, third sector advocacy groups and patient and public involvement (PPI). However, stakeholder involvement does not replace the literature search but serves to supplement, tailor and expedite it.29 32

Our focus is a clearly defined intervention (the diagnostic pathway), associated with specific outcomes (high quality and timely) within a particular set of parameters (autism/CAMHS services in the UK); this is consistent with a realist focus on ‘theory-driven, contextually relevant interventions that are likely to be associated with specific outcomes within a particular set of parameters’ (Saul et al, p3).29 Our initial Programme Theory, based on NICE (2011) guidance, the project team and Expert Stakeholder Group, states:

If there is a MDT assessment by a team with competencies in child neurodevelopment and mental health (context), then Autism will be recognised as a complex condition that relies on detailed history and observation across settings (mechanism) to diagnose it. This will lead to accurate diagnosis, recognition of associated co-occurring conditions such as ADHD and intellectual disability (outcome), and the ruling out of complex differential diagnoses. This will also create, whilst not an explicit part of this project, an accurate picture of a child’s strengths and needs to inform individualised packages of support and intervention through health, education and social care (outcome).

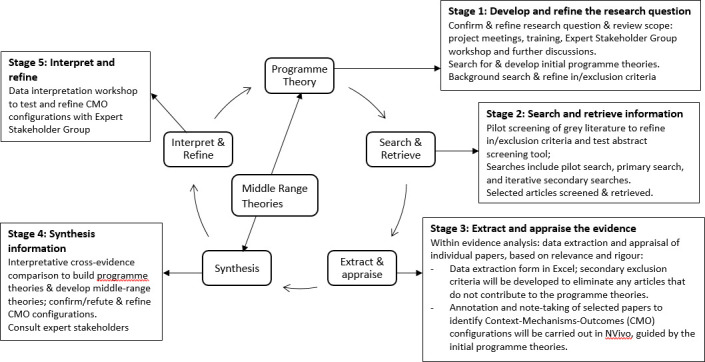

We will follow the five stages of RRR,29 including developing and refining the scope of the review; searching and identifying information; extracting and appraising the evidence; synthesising and interpreting the evidence; validation with expert stakeholders and dissemination (figure 1). Preliminary explanations will then be tested within later stages of the whole project. Table 1 provides a summary of realist terms.

Figure 1.

RE-ASCeD RRR stages. RE-ASCeD, Realist Evaluation of Autism ServiCe Delivery; RRR, rapid realist review.

Table 1.

Realist terminology

| Term | Explanation36 40 |

| Context | Refers to the ‘backdrop’ of interventions (in this case the diagnostic pathway), or anything outside the parameters of the intervention that might affect it, for example, shortages of community paediatricians. Context can also be understood as ‘any condition that triggers and/or modifies the mechanism.’40 |

| Mechanism | The generative force that leads to an outcome of interest; usually hidden and context-sensitive. Mechanisms consist of intervention resources and how people respond to them. |

| Outcome | The outcome, intended or unintended, of a complex intervention such as timely assessment of possible autism in children. Outcomes can be initial, intermediate or final. |

| CMO configuration(s) | CMO configuring is a heuristic used to general causative explanations relating to outcomes. The process explores the relationship between an outcome of interest in a particular context; and the underlying mechanisms. CMO configurations are a way of refining theory about aspects of the intervention, or the intervention overall. |

| Programme theory | This is the overarching theory of how a particular complex intervention may work; it draws on evidence, data and creative (retroductive) thinking to seek explanations of how, why and in what contexts an intervention works. The initial programme theory is tested and refined in an iterative process throughout the RRR. |

| Programme areas | These are areas, or themes, within the overarching theory, for example, GP involvement in the autism referral pathway. |

| MRT | An explanatory theory that can be used to explain a complex intervention, or aspects of it. While CMO configurations are specific to the intervention under investigation, and underpin the programme theory, MRTs are more generic and have wider application. |

CMO, Context-Mechanisms-Outcomes; GP, general practitioner; MRT, middle range theory; RRR, rapid realist review.

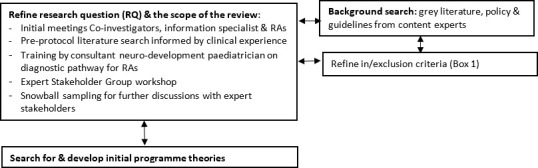

Stage 1: developing and refining the research question (September 2019 to January 2020)

The first stage aims to confirm and refine the research question and scope, and prioritise areas for investigation (figure 2). This stage is in progress through ongoing discussions with our chief investigator (IM, consultant community paediatrician), co-investigators, NHS England and our Expert Stakeholder Group.

Figure 2.

Developing and refining the research question.

The RRR team (the core researchers working on the RRR within the larger project team) has carried out preliminary work for Stage 1, as follows:

An initial preprotocol literature search informed by clinical experience (IM)

Discussion within the RE-ASCeD project team to define the scope and remit of review

Training on the diagnostic pathway for the research assistants (RAs: VA and WZ) by a consultant neurodevelopmental paediatrician, also a co-investigator.

Expert Stakeholder Group workshop to help confirm and refine the research questions, inclusion and exclusion criteria (box 1), and identify salient documents (policy and grey literature) for review.32 Telephone discussions were carried out with expert stakeholders who were unable to attend the workshop.

Box 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Primary inclusion criteria:

Children (preschool, primary or secondary school and adolescents) with autism spectrum disorder OR autism spectrum condition AND

UK healthcare system (England, Scotland, Wales and/or Northern Ireland) AND

Published 2011 onwards AND

Relates to diagnostic pathway and model of service provision OR

Relates to assessment process for example, single discipline (paediatric consultant) or interdisciplinary.

Primary exclusion criteria:

Non-UK based literature.

Relates only to adult diagnostic pathway.

Relates only to tertiary services.

Only relates to treatment.

Relates to support services only after diagnosis.

Stage 1 activities will function as a starting point to develop initial programme areas which will be discussed with the Expert Stakeholder Group before moving to Stage 2.

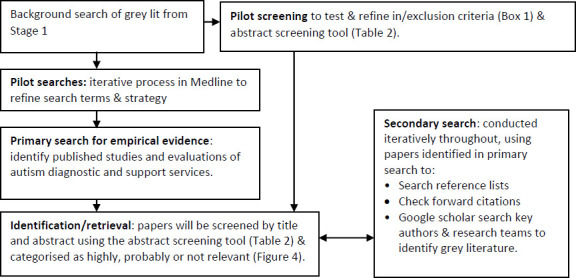

Stage 2: searching and retrieving information (January to February 2020)

Stage 2 will start with screening information from the background search carried out in Stage 1, which we anticipate will include national policy/guidelines and grey literature on local implementation of the diagnostic pathway (figure 3). Two experienced RAs (VA and WZ) will conduct the pilot screening initially by title and abstract, and then with full text for those deemed relevant. The pilot screening will help further develop the abstract screening tool (table 2) coproduced by the RRR team and expert stakeholders in Stage 1.

Figure 3.

Searching and retrieving information.

Table 2.

Abstract screening tool

| Ranking | Descriptions |

| Highly relevant | Primary focus is on diagnostic pathway whether the model is autism specific, autism/CAMHS, integrated neurodevelopmental pathway; AND |

| Relates to certain aspects of diagnostic pathway for example, skills mix OR | |

| Comments on implementation issues and/or contextual issues &/or outcomes OR | |

| Relates to quality or timeliness or cost-effectiveness of diagnostic pathway OR | |

| Relates to service user experience OR | |

| Relates to support services up to diagnosis OR | |

| Explores stakeholder perspective (commissioners, clinicians, other) up to diagnosis | |

| Probably relevant | Some description of diagnostic pathway but not the main focus |

| Little information on implementation, context or outcomes | |

| Limited reference to quality, timeliness or cost-effectiveness of diagnostic pathway | |

| Briefly refers to service user experience | |

| Briefly refers to support services up to (and/or post) diagnosis | |

| Explores stakeholder perspective (commissioners, clinicians, other) up to (and/or post) diagnosis | |

| Mostly not relevant but contains some ‘nuggets’ | |

| Not relevant | Does not meet above criteria for example, only focuses on post-diagnosis or adults |

CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

The search carried out by the information technologist will be performed in three stages.33 First, iterative pilot searches will be carried out in Medline to refine the search strategy. The pilot searches will use a combination of text terms and synonyms appearing in the title, abstract and keywords in combination with index terms (MeSH subject headings) using the OR operator. These concepts will then be combined using the AND operator. By checking synonyms and further exploring MeSH index terms, the search can be tailored to ensure relevant papers are retrieved. The strategy will be modified to increase the sensitivity of the search by excluding some terms, including others, trialling MeSH terms or dropping the keyword field and restricting to the abstract and title fields only. Limits are papers written in English and published after 2011, when the NICE guidelines for recognition, referral and diagnosis of autism in under 19s was published.20 The search will be restricted to UK only, given specific NHS context, but if insufficient evidence is identified, a secondary search will include comparable countries (eg, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand), although with different healthcare systems.

Second, the primary search for empirical evidence will be used to identify published studies and evaluations of autism diagnostic and support services. It will search databases including Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Social Policy & Practice (Ovid), CINAHL Plus (EBSCO), Cochrane Library and Web of Science (Clarivate) with limits of dates (2011–current), language (English) and country (UK only). Each database varies with different index terms (or none) and searchable fields which means the strategy will be amended for each database. We will include studies of any design including randomised controlled trials, controlled studies, effectiveness studies, uncontrolled studies, interrupted time series studies, cost-effectiveness studies, process evaluations and qualitative studies. To understand the complexities of the autism diagnostic pathway, we will take account of literature reporting all stakeholder perspectives including those of children/adolescents, parents, clinicians, service managers and commissioners.

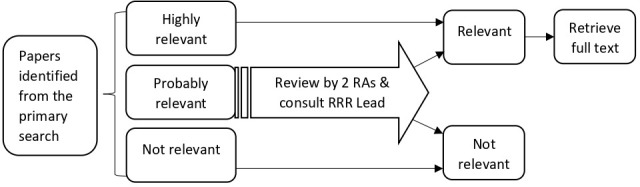

Primary search results will be screened and retrieved by the RAs (VA and WZ), initially by title and abstract using the abstract screening tool (table 2) to identify articles as highly, probably or not relevant. All ‘probably relevant’ articles will be reviewed by both RAs; where undecided, one co-investigator (PW) will decide. Full text will be retrieved for all papers deemed relevant (figure 4). Endnote will be used to store and categorise the search results by the three relevance categories.

Figure 4.

The screening process of primary search results. RAs, research assistants; RRR, rapid realist review.

Lastly, secondary searching will be conducted iteratively throughout the review with input from our Expert Stakeholder Group. The two RAs will use papers identified in the primary and background search to look through reference lists for relevant articles; check forward citations; and search key authors and research teams to identify further literature, using Google scholar. The RAs will screen the secondary search results and relevant papers will be included. Prior to data extraction, our expert stakeholders will be consulted to ensure that all key literature is included; this step will be repeated at the consolidation workshop (Stage 5).

Stage 3: extracting and appraising the evidence (February to March 2020)

Within evidence analysis involves data extraction and appraisal of individual papers based on relevance and rigour. Data extraction will be carried out using a hybrid approach.34 First, basic details from each article will be recorded in a data extraction form in Microsoft Excel 2016; the tool will include information about the diagnostic pathway, service delivery characteristics and any evidence related to intended (or unintended) outcomes.33 Secondary exclusion criteria will be developed to eliminate articles that do not contribute to the overall programme theory. Second, included articles will be imported into NVivo under ‘sources’; the coding framework will have one node for each programme area (eg, the skills mix of the diagnostic team) and sub-nodes will be created as appropriate. The RAs will code relevant extracts of each paper, using annotation and note-taking to record comments related to context, outcomes and possible mechanisms.34 Annotations and note-taking will serve as an audit trail and a record of our decision-making processes and rationales for developing our programme theories.35

For both stages of data extraction and analysis, the two RAs will review three papers jointly and three independently and then compare findings; the remaining papers will be split and reviewed independently by one RA. For 20% of papers, a series of calibration exercises will be undertaken by the RRR lead (PW).

Appraisal of evidence will be based on the concepts of relevance, rigour and richness.36 37 Relevance refers to whether the evidence can contribute to theory building and/or testing; evidence can be highly relevant but not necessarily trustworthy. Rigour questions whether the methods used to generate the data are trustworthy and credible (or plausible); this includes ‘nuggets of wisdom’ (Pawson, p127)38 in otherwise methodologically weak studies. Alongside quality, evidence will be appraised in terms of how credible or coherent it is, which involves examining the reasoning behind the argument and considering the coherence of the programme theory developed from the data.30 Richness refers to the existence and quality of causal insights and encompasses rich descriptions of context, process or outcomes.36

When the RAs are uncertain about the extraction or appraisal of a paper, this will be discussed with the RRR lead (PW).

Stage 4: synthesising information (March to May 2020)

Our ‘hybrid’ approach to data extraction in Stage 3 will aid the process of distilling context and outcomes thereby allowing identification of underlying mechanisms within each programme area. The aim is to make sense of our initial and evolving programme theory. Evidence synthesis will use interpretative cross-evidence comparison to interrogate the data: we will move iteratively between analysing specific examples (ie, extracts from one study); comparing and contrasting findings from different studies while also considering their respective methodological strengths and weaknesses; further searching to interrogate, confirm or refute CMO configurations; and refining the overall programme theory.34 39 This retroductive process of exploring observable patterns to discover underlying mechanisms will involve the whole RRR team to ensure validity and consistency of theory building37; we will also consult with expert stakeholders iteratively. Cross-evidence analysis will allow us to develop and refine CMO configurations, which we will align with our research questions to build or search for existing explanatory middle range theories (MRTs). At a practical level, we will continue to use annotations and linked memos in NVivo to maintain transparency and capture decision-making but will also use simple tables in a Microsoft Word 2016 document, one per programme area, to capture (multiple) CMO configurations which will be linked back to the evidence, with commentary on possible MRTs (either existing MRTs and/or evolving ones).

Stage 5: interpreting and refining (May to June 2020)

We will run a data interpretation workshop with our Expert Stakeholder Group to test and refine CMO configurations, which will further contribute to the refinement of our final programme theories and MRTs. Our Expert Stakeholders will also be asked to suggest any additional literature which helps elucidate the programme theories. Framed by the RRR approach, our final report will highlight service models that in certain contexts will trigger specific mechanisms that lead to outcomes of interest.29

Patient and public involvement

Engaging PPI representatives from the start, as part of our Expert Stakeholders Group, has enabled us to focus the review on questions that stakeholders are most interested in answering and will enable identification of salient documents for review, many of which are grey literature or unpublished.32 PPI involvement is integral to the overall project, has been embedded into the review protocol and will be particularly helpful when synthesising and interpreting the data (Stage 5).

Limitations

We are explicitly setting pragmatic limits on the literature search (Stages 1–2) as RRR allows,29 and acknowledge that it cannot be as extensive as a full realist review, given an externally imposed time limit. We are mindful of comprehensiveness without accruing too much extraneous material in the process. Engaging with our stakeholders throughout the process will enable an iterative approach to identifying relevant literature. The search is limited to UK literature because this is pertinent to our research questions but we acknowledge that we may miss literature from other similar health systems that could inform our programme theories. We are also limiting the secondary search in that we intend to do forward citations for key papers and authors only. However, while we have set limits on the literature search, the synthesis (Stages 3–5) is as extensive as that for a full realist review.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anna Peckham, our information specialist, for critically appraising the search strategy. We would also like to acknowledge our co-investigators on the RE-ASCeD project team who contributed to the wider protocol (in alphabetical order): Amanda Allard, Council for Disabled Children; Professor Heather Gage, University of Surrey; Dr Victoria Grahame, Cumbria, Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust; Dr Lorcan Kenny, Autistica; Professor Jeremy Parr, Newcastle University, Cumbria, Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Trust, and Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Dr Venkat Reddy, Peterborough Child Development Centre; Dr Gráinne Saunders, West Sussex Parent Carer Forum, PPI Partner; Peter Williams, University of Surrey; and Kat Wilmore, PPI partner, Sussex Autism Support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @WenjingZhang_

Contributors: VA and WZ were involved in writing all drafts of this paper. PW, WF and IM did substantial contribution to writing protocol for the overall RE-ASCeD project and commented on final draft of this protocol.

Funding: NHS England funds for this project derived from the child and young person mental health transformation funding stream, via the Learning Disability and Autism Directorate (direct quote from NHS England letter dated 28/8/2019).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. England NHS Nhs long term plan: learning disability and autism. section 3.31-3.36. England N, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, et al. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the special needs and autism project (SNAP). The Lancet 2006;368:210–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh Y-J, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res 2012;5:160–79. 10.1002/aur.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018;67:1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waugh I. The prevalence of autism (including Asperger’s Syndrome) in school age children in Northern Ireland 2019. Department of health ed Northern Ireland, Belfast, 2019: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Organization WH International classification of diseases XI beta draft: 6A02 autism spectrum disorder. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Health and Social Care Information Centre ND Instructions and guidance notes: assuring transformation, 2018. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-collections-and-data-sets/data-collections/assuring-transformation/content#guidance [Accessed 05 Feb 2020].

- 9. Buescher AVS, Cidav Z, Knapp M, et al. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:721–8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hayes SA, Watson SL. The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43:629–42. 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National initiative for autism Screening and assessment. National autism plan for children (NapC) plan for identification, assessment, diagnosis and access to early interventions for pre-school and primary school aged children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD. London, 2003: 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- 12. BACCH A workforce strategy for community paediatrics. London: British association for community child health, 2019: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Care Quality Commission, Ofsted . Local area send inspections: 1 year on, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Male I, Farr W, Gain A, et al. How much does it cost to assess a child for possible autism spectrum disorder in the UK National health service: an observational study. European Academy of Childhood Disability, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutherford M, Burns M, Gray D, et al. Improving efficiency and quality of the children's ASD diagnostic pathway: lessons learned from practice. J Autism Dev Disord 2018;48:1579–95. 10.1007/s10803-017-3415-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galliver M, Gowling E, Farr W, et al. Cost of assessing a child for possible autism spectrum disorder? an observational study of current practice in child development centres in the UK. BMJ Paediatr Open 2017;1:e000052. 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brett D, Warnell F, McConachie H, et al. Factors affecting age at ASD diagnosis in UK: no evidence that diagnosis age has decreased between 2004 and 2014. J Autism Dev Disord 2016;46:1974–84. 10.1007/s10803-016-2716-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kentrou V, de Veld DM, Mataw KJ, et al. Delayed autism spectrum disorder recognition in children and adolescents previously diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Autism 2019;23:1065–72. 10.1177/1362361318785171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rutherford M, McKenzie K, Forsyth K, et al. Why are they waiting? exploring professional perspectives and developing solutions to delayed diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults and children. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2016;31:53–65. 10.1016/j.rasd.2016.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Autism spectrum disorder in under 19S: recognition, referral and diagnosis (CG128. London, UK, 2011: 1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lord C, Luyster R, Guthrie W, et al. Patterns of developmental trajectories in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:477–89. 10.1037/a0027214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whitehouse A, Evans K, Eapen V. The diagnostic process for children, adolescents and adults referred for assessment of autism spectrum disorder in Australia: a national guideline (draft version for community consultation. Autism CRC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Penner M, King GA, Hartman L, et al. Community General pediatricians' perspectives on providing autism diagnoses in Ontario, Canada: a qualitative study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2017;38:593–602. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jordan E, Farr W, Fager S, et al. Pirate adventure autism assessment app: a new tool to aid clinical assessment of children with possible autistic spectrum disorder : Powell W, Rizzo A, Sharkey P, et al., Rehabilitation: innovation and challenges in the use of virtual reality technologies NY. US: Nova Publishers, 2017: 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Male I, Reddy V. Should ADHD, ASD& related services be delivered in an integrated way? BACCH NEWS, 2018: 20–2. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crane L, Chester JW, Goddard L, et al. Experiences of autism diagnosis: a survey of over 1000 parents in the United Kingdom. Autism 2016;20:153–62. 10.1177/1362361315573636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reed P, Osborne LA. Diagnostic practice and its impacts on parental health and child behaviour problems in autism spectrum disorders. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:927–31. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-301761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palmer E, Ketteridge C, Parr JR, et al. Autism spectrum disorder diagnostic assessments: improvements since publication of the National autism plan for children. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:473–5. 10.1136/adc.2009.172825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saul JE, Willis CD, Bitz J, et al. A time-responsive tool for informing policy making: rapid realist review. Implement Sci 2013;8:103. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong G. Data gathering in realist reviews: looking for needles in haystacks. Doing realist research. London: SAGE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pawson R. Evidence-Based policy: a realist perspective. London: SAGE Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Willis CD, Saul JE, Bitz J, et al. Improving organizational capacity to address health literacy in public health: a rapid realist review. Public Health 2014;128:515–24. 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsang JY, Blakeman T, Hegarty J, et al. Understanding the implementation of interventions to improve the management of chronic kidney disease in primary care: a rapid realist review. Implementation Science 2015;11 10.1186/s13012-016-0413-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Weetman K, Wong G, Scott E, et al. Improving best practise for patients receiving hospital discharge letters: a realist review protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018353. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gilmore B, McAuliffe E, Power J, et al. Data analysis and synthesis within a realist evaluation: toward more transparent methodological approaches. Int J Qual Methods 2019;18:1609406919859754 10.1177/1609406919859754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jagosh J, Pluye P, Macaulay AC, et al. Assessing the outcomes of participatory research: protocol for identifying, selecting, appraising and synthesizing the literature for realist review. Implement Sci 2011;6:24. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 2013;11:21. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pawson R. Digging for Nuggets: How ‘Bad’ Research Can Yield ‘Good’ Evidence. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2006;9:127–42. 10.1080/13645570600595314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. MacDonald M, Pauly B, Wong G, et al. Supporting successful implementation of public health interventions: protocol for a realist synthesis. Syst Rev 2016;5:54. 10.1186/s13643-016-0229-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jagosh J, Pluye P, Wong G, et al. Critical reflections on realist review: insights from customizing the methodology to the needs of participatory research assessment. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:131–41. 10.1002/jrsm.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.