Abstract

目的

分析减低剂量预处理单倍型外周血造血干细胞移植(RIC-haplo-PBSCT)治疗50岁以上恶性血液肿瘤患者的疗效。

方法

18例50岁以上恶性血液肿瘤患者纳入研究,男8例,女10例,中位年龄52(50~66)岁;急性髓系白血病(AML)8例,慢性髓性白血病(CML)2例,骨髓增生异常综合征(MDS)5例,急性淋巴细胞白血病(ALL)2例,急性NK细胞白血病(ANKL)1例;采用FAB+ATG(氟达拉滨+阿糖胞苷+白消安+兔抗人胸腺细胞免疫球蛋白)减低剂量预处理方案,输注供者高剂量非去T细胞外周血造血干细胞(PBSC),应用强化移植物抗宿主病(GVHD)预防方案及感染防控措施。

结果

16例患者在移植后15 d获得完全供者嵌合,其中1例在移植后1个月发生移植排斥,其余2例在移植后15 d为混合嵌合并于移植后1个月发生移植排斥。急性GVHD发生率为61.1%(95%CI 49.6%~72.6%),Ⅱ~Ⅳ度急性GVHD发生率为35.4%(95%CI 21.1%~49.7%),Ⅲ/Ⅳ度急性GVHD发生率为13.8%(95%CI 4.7%~22.9%)。2年慢性GVHD累积发生率为38.2%(95%CI 25.5%~50.9%),未发生广泛型慢性GVHD。中位随访14.5(3~44)个月,2年总生存率、无病生存率分别为72.6%(95%CI 60.1%~85.1%)、63.7%(95%CI 49.2%~78.2%),2年累积复发率为31.2%(95%CI 16.5%~45.9%),2年非复发死亡率为12.5%(95%CI 4.2%~20.8%)。

结论

RIC-haplo-PBSCT治疗50岁以上恶性血液肿瘤患者可获得较好的疗效。

Keywords: 移植预处理, 单倍型外周血造血干细胞移植, 血液肿瘤

Abstract

Objective

To analyze the efficacy of HLA-haploidentical peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (haplo-PBSCT) following reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimen to treat the patients with hematological malignancies who were older than 50 years old.

Methods

Eighteen patients with hematological malignancies over 50 years were enrolled, including 8 male and 10 female patients. The median age of all patients was 52 (range: 50–66) years. Of them, 8 patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 2 chronic myelocytic leukemia (CML), 5 myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), 2 acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and 1 aggressive natural killer cell leukemia (ANKL). All patients received fludarabine, cytarabine and melphalan with rabbit anti-human thymocyte globulin (FAB+rATG regimen) and transplanted with high dose non-T cell-depleted peripheral hematopoietic stem cells from donors. Enhanced graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis and infection prevention were administered.

Results

Fifteen days after transplantation, 16 patients achieved complete donor chimerism. One of them rejected the donor graft completely at thirty days after transplantation, and the other 2 patients had mixed chimerism 15 days after transplantation and converted to complete recipient chimerism at 30 days after transplantation. The cumulative incidence of acute GVHD (aGVHD) was 61.1% (95%CI49.6%–72.6%). The incidence of grade Ⅱ–Ⅳ aGVHD was 35.4% (95%CI 21.1%–49.7%), whereas grade III-IV was 13.8% (95%CI 4.7%–22.9%). The 2-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) rate was estimated at 38.2% (95%CI 25.5%–50.9%). Patients were followed-up for a median of 14.5 months (range, 3–44 months). The Kaplan Meier estimates of 2-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) was 72.6% (95%CI 60.1%–85.1%) and 63.7% (95%CI 49.2%–78.2%), respectively. The 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse and non-relapse-mortality (NRM) was 31.2% (95%CI 16.5%–45.9%) and 12.5% (95%CI 4.2%–20.8%), respectively.

Conclusion

RIC-haplo-PBSCT protocol can achieve better results in patients with hematologic malignancies over 50 years old.

Keywords: Transplantation conditioning, Haploidentical peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Hematologic malignancy

减低剂量预处理(RIC)异基因造血干细胞移植(allo-HSCT)是近年来发展起来的一种新型移植模式,移植相关死亡率明显降低[1]–[2]。RIC-allo-HSCT在HLA同胞全相合及无关供者中开展较多且效果较好[3]–[4]。但RIC方案在单倍型造血干细胞移植(haplo-HSCT)开展较晚且报道较少。我中心设计了独特的RIC-haplo-PBSCT模式,为难以耐受清髓性allo-HSCT且找不到HLA全相合供者的患者提供治疗选择。本研究我们对18例接受RIC-haplo-PBSCT治疗的50岁以上恶性血液肿瘤患者进行回顾性分析。

病例与方法

1.病例:本研究纳入2014年1月至2018年8月在我院血液病中心行RIC-haplo-PBSCT的50岁以上恶性血液肿瘤患者18例。男8例,女10例,中位年龄为52(50~66)岁;汉族12例,其他民族6例;原发病:急性髓系白血病(AML)8例,慢性髓性白血病(CML)2例,骨髓增生异常综合征(MDS)5例,急性淋巴细胞白血病(ALL)2例,急性NK细胞白血病(ANKL)1例;供受者ABO血型相合8例,血型不合10例(主要不合、次要不合各5例);供者中位年龄28(22~48)岁,女供男1例,男供男7例,男供女8例,女供女2例;供受者关系:兄弟姐妹2例,子女供父母16例;欧洲血液和骨髓移植组织(EBMT)危险因素积分[5]:中危11例,高危7例;造血干细胞移植合并症指数(HCT-CI):0分1例,1~2分13例,≥3分4例;18例患者的临床资料详见表1。

表1. 18例接受减低剂量预处理单倍型外周血造血干细胞移植患者的临床资料.

| 例号 | 移植前诊断 | 疾病状态 | 患者/供者 |

HLA配型 | EBMT | HCT-CI | 回输MNC(×108/kg) | 回输CD34+细胞(×106/kg) | |||||

| 年龄(岁) | 性别 | 血型 | CMV-DNA | CMV-IgG | 关系 | ||||||||

| 1 | AML | CR1 | 53/23 | 男/男 | A/AB | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 3/6 | 中危 | 2 | 18.50 | 8.00 |

| 2 | MDS(RAEB-2) | PR | 57/39 | 女/女 | AB/B | −/− | +/+ | 同胞 | 4/6 | 高危 | 2 | 12.51 | 6.20 |

| 3 | CML | CP | 64/41 | 男/女 | O/O | −/− | −/+ | 子女 | 3/6 | 高危 | 3 | 9.05 | 4.50 |

| 4 | AML | CR1 | 61/36 | 女/男 | B/AB | −/− | +/− | 子女 | 3/6 | 中危 | 1 | 14.79 | 7.30 |

| 5 | ANKL | CR1 | 50/26 | 男/男 | AB/B | −/+ | +/+ | 子女 | 3/6 | 中危 | 3 | 17.50 | 11.20 |

| 6 | ALL | CR1 | 50/24 | 女/男 | O/O | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 3/6 | 中危 | 2 | 18.90 | 8.23 |

| 7 | AML | CR1 | 52/48 | 女/男 | A/A | −/− | +/+ | 同胞 | 3/6 | 中危 | 2 | 16.38 | 8.00 |

| 8 | AML | CR1 | 52/31 | 男/男 | A/B | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 4/6 | 中危 | 3 | 16.68 | 7.67 |

| 9 | MDS(RAEB-1) | 未治 | 50/26 | 女/男 | B/O | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 3/6 | 中危 | 1 | 14.18 | 7.00 |

| 10 | AML | CR1 | 50/27 | 女/男 | B/O | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 3/6 | 中危 | 1 | 14.85 | 7.10 |

| 11 | CML | AP | 60/28 | 女/男 | O/O | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 4/6 | 高危 | 0 | 19.84 | 17.80 |

| 12 | MDS(RAEB-1) | PR | 50/22 | 男/男 | O/O | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 5/10 | 高危 | 2 | 11.65 | 7.41 |

| 13 | AML | CR1 | 55/30 | 男/男 | A/A | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 5/10 | 中危 | 1 | 13.40 | 6.20 |

| 14 | MDS(RAEB-1) | PR | 51/26 | 男/男 | B/A | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 6/10 | 高危 | 1 | 12.79 | 6.30 |

| 15 | Ph+ ALL | CR1 | 53/27 | 女/女 | O/A | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 6/10 | 中危 | 2 | 13.67 | 6.30 |

| 16 | AML | CR2-rel1 | 54/25 | 女/男 | AB/B | −/− | -/+ | 子女 | 5/10 | 高危 | 2 | 16.50 | 8.37 |

| 17 | MDS(RAEB-2) | CR1 | 66/41 | 男/男 | O/O | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 5/10 | 中危 | 2 | 15.21 | 11.85 |

| 18 | AML | CR2 | 52/29 | 女/男 | O/O | −/− | +/+ | 子女 | 5/10 | 高危 | 3 | 21.65 | 10.63 |

注:AML:急性髓系白血病;ALL:急性淋巴细胞白血病;MDS:骨髓增生异常综合征;CML:慢性髓性白血病;ANKL:急性NK细胞白血病;EBMT:欧洲骨髓移植登记组危险因素积分;HCT-CI:造血干细胞移植合并症指数;CMV:巨细胞病毒;MNC:单个核细胞;CR1:第1疗程完全缓解;CR2:第2疗程完全缓解;PR:部分缓解;CP:慢性期;AP:加速期;rel1:第1次复发

2.预处理方案:18例患者均采用FAB+ATG减低剂量预处理方案:氟达拉滨(Flu)30 mg·m−2·d−1,−9 d~−5 d静脉滴注;阿糖胞苷(Ara-C)1 g·m−2·d−1(或2 g·m−2·d−1),−9 d~−5 d静脉滴注;白消安(Bu)3.2 mg·kg−1·d−1,−4 d、−3 d静脉滴注;兔抗人胸腺细胞免疫球蛋白(ATG)2.5 mg·kg−1·d−1,−4 d~−1 d静脉滴注。

3.造血干细胞动员、采集与输注:外周血造血干细胞的动员采用重组人粒细胞集落刺激因子7~10 µg·kg−1·d−1皮下注射,于动员的第5、6天采集外周血干细胞,体重过低的供者于动员第4~6天采集(供受者体重差小于10 kg)或提前冻存干细胞(供受者体重差大于等于10 kg)。回输单个核细胞(MNC)中位数为15.03(9.05~21.65)×108/kg,CD34+细胞中位数为7.54(4.50~17.80)×106/kg。

4.GVHD的诊断、防治及支持治疗:急性GVHD和慢性GVHD按西雅图国际标准进行评分及各脏器分级。采用加强的GVHD预防方案:环孢素A:−5 d开始2.5 mg·kg−1·d−1静脉滴注,+30 d后改为(4~5)mg·kg−1·d−1口服;甲氨蝶呤:+1 d 15 mg·m−2·d−1,+3 d、+6 d 10 mg·m−2·d−1,静脉滴注;霉酚酸酯:1.0 g/d,−1 d~+100 d口服;抗CD25单抗:12 mg/m2,+1 d、+2 d静脉滴注;地塞米松:5 mg/d,+1 d~+15 d静脉滴注,之后逐渐减量,+30 d停用。对于发生急性GVHD的患者,给予甲泼尼龙1~2 mg·kg−1·d−1,疗效欠佳者加用抗CD25单抗。给予细菌、真菌、病毒及卡氏肺孢子虫感染预防措施。静脉丙种球蛋白0.4 g·kg−1·d−1每周1次共4次,4周后根据患者具体情况每月1次,直到1年。

5.造血重建及嵌合率的监测:中性粒细胞绝对计数(ANC)≥0.5×109/L持续3 d为中性粒细胞植活;在脱离血小板输注情况下PLT≥20×109/L持续7 d为血小板植活。完全嵌合指供受者嵌合率≥95%,混合嵌合指供受者嵌合率5%~95%,微嵌合指供受者嵌合率<5%。植入后常规进行外周血嵌合率监测,移植后3个月每15 d检测1次,移植后第4个月~1年每30 d检测1次,此后每3个月检测1次。

6.随访:采用电话及查阅病历资料的方式进行随访。随访截止日期为2018年12月31日,中位随访时间14.5(3~44)个月。总生存(OS)时间:造血干细胞回输至随访截止或死亡的时间;无病生存(DFS)时间:造血干细胞回输至随访截止至疾病复发的时间。

7.统计学处理:采用SPSS 21.0软件进行数据分析。OS率、DFS率、累积复发率、非复发死亡率(NRM)、急性GVHD发生率、慢性GVHD发生率采用Kaplan-Meier法计算。

结果

1.造血重建:全部18例患者均获得造血重建,中性粒细胞中位植入时间为15.5(12~29)d,血小板中位植入时间16(11~34)d。16例患者在移植早期获得稳定、完全供者嵌合,其中1例在移植后1个月发生移植排斥及疾病复发,其余2例患者为混合嵌合并在移植后1个月发生移植排斥。3例出现移植排斥的患者中,2例患者未行供者特异性抗体(DSA)检测,1例患者DSA检测结果为“HLA-Ⅰ类抗体弱阳性、HLA-Ⅱ类强阳性”,移植前未行特殊处理。3例发生移植排斥的患者中1例失访,1例复发生存,1例缓解生存。

2.GVHD发生情况:急性GVHD发生率为61.1%(95%CI 49.6%~72.6%),Ⅱ~Ⅳ度、Ⅲ/Ⅳ度急性GVHD发生率分别为35.4%(95%CI 21.1%~49.7%)、13.8%(95%CI 4.7%~22.9%)。急性GVHD的中位发生时间为45(18~84)d。发生部位:皮肤7例、肝脏4例、口腔2例,累及2个部位以上2例。仅有1例患者死于肝脏急性GVHD,其余患者均得到较好控制。2年慢性GVHD发生率为38.2%(95%CI 25.5%~50.9%),均为局限型(皮肤2例,口腔2例,肝脏1例),未发生广泛型慢性GVHD。

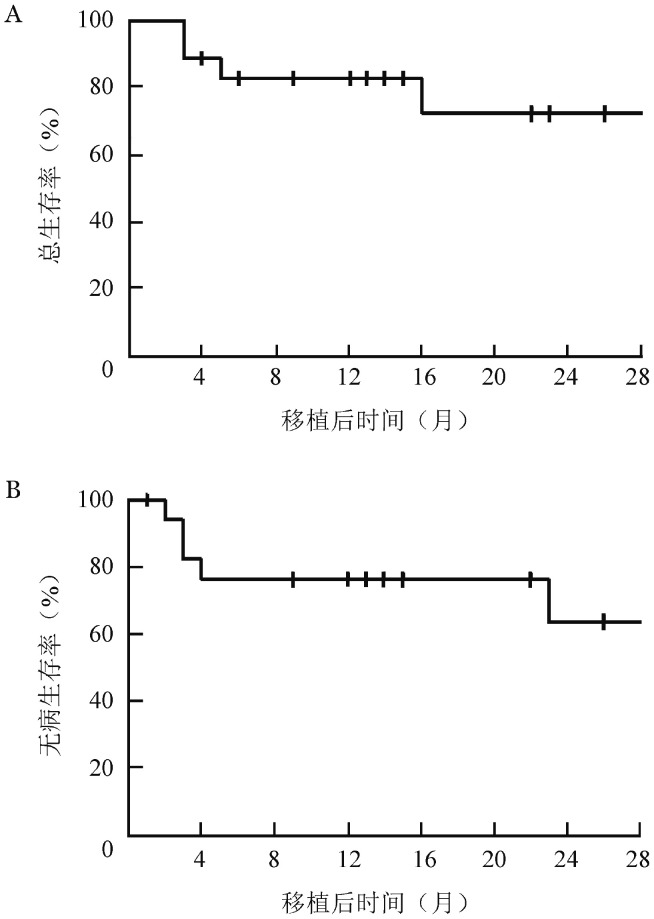

3.生存及复发:至随访截止,18例患者中13例无病存活,复发死亡3例,非复发死亡2例(感染性休克、严重急性GVHD并发多脏器功能衰竭各1例)。1、2年OS率分别为83.0%(95%CI 74.0%~92.0%)、72.6%(95%CI 60.1%~85.1%),1、2年DFS率分别为76.5%(95%CI 66.2%~86.8%)、63.7%(95%CI 49.2%~78.2%),1、2年累积复发率分别为17.5%(95%CI 8.3%~26.7%)、31.2%(95%CI 16.5%~45.9%),1、2年NRM均为12.5%(95%CI 4.2%~20.8%)。生存曲线见图1。

图1. 18例50岁以上恶性血液肿瘤患者减低剂量预处理单倍型造血干细胞移植后总生存曲线(A)和无病生存曲线(B).

4.移植后相关感染并发症:1例患者移植后发生CMV血症,2例患者发生出血性膀胱炎,2例患者发生带状疱疹,治疗后均好转。肺部感染6例,其中细菌感染4例,真菌感染1例,间质性肺炎1例,均治愈。均未发生EB病毒感染及EB病毒相关淋巴细胞增殖性疾病(PTLD)。

讨论

allo-HSCT是恶性血液肿瘤的重要治疗手段,预处理是移植过程的重要环节。经典的清髓性预处理并发症较多,移植相关死亡率较高。既往针对RIC-HSCT的研究主要集中于同胞全相合及无关供者移植[1]–[4],[6]–[8]。在我国,大部分患者缺乏全相合同胞供者,全相合无关供者也难以及时找到[9]。因此,haplo-HSCT越来越多地应用于临床并取得了长足进步[10]–[12]。

已有多个RIC方案应用于haplo-HSCT[13]–[15],但目前无统一方案。经典的RIC方案由一种烷化剂联合嘌呤类似物(通常为Flu)、小剂量全身照射(TBI)合用或不合用其他化疗药物组成[1]–[2],[16]。本中心自2002年起应用独特的清髓性haplo-PBSCT模式治疗恶性血液肿瘤取得了较好的疗效[17]–[18]。杨廷等[19]综述了国内外的RIC-haplo-HSCT的研究结果,未见到应用FAB+ATG作为RIC方案的文献报道。本中心针对50岁以上且体质较弱而不能耐受清髓性预处理、无全相合供者可供选择的血液肿瘤患者设计的RIC-haplo-PBSCT模式具有以下特点:①减低剂量的FAB+ATG预处理方案;②G-CSF动员的非体外去T细胞的高剂量供者PBSC输注;③加强的GVHD预防方案;④强化的感染防控方案。

既往的RIC-HSCT研究表明影响移植疗效的问题主要是植入失败和疾病复发。根据较早期的报道减低预处理剂量全相合异基因造血干细胞移植(RIC-MS-HSCT)中的原发植入失败率高达30%[7],[20]–[21]。近年来,尽管RIC方案不断完善,RIC-haplo-HSCT仍具有较高的原发植入失败发生率[22]–[23]。本研究18例患者中16例植入成功,可能的原因:①预处理方案中包含高剂量Ara-C,更好地去除了患者体内的记忆T细胞,对供者造血干细胞的植入起到促进作用。②非体外去T细胞的高剂量PBSC输注克服了HLA屏障导致的原发植入失败,高剂量PBSC可明显促进植入[24]–[25]。

本组病例的最大特点是高剂量非体外去T细胞PBSC输注。本研究中输注的供者MNC为15.03(9.05~21.65)×108/kg,CD34+细胞为7.54(4.50~17.80)×106/kg。这在国内外尚未见报道。最近一项关于无关供者外周血干细胞移植(UD-PBSCT)的回顾性研究显示,高剂量PBSC与急性GVHD发生率增高呈正相关,而无其他获益[26],但这项研究中的预防GVHD措施并无特殊。本组病例均接受强化预防GVHD处理,虽然Ⅰ~Ⅳ度急性GVHD发生率较高,但Ⅱ~Ⅳ度急性GVHD(尤其是Ⅲ/Ⅳ度急性GVHD)发生率较低,且临床较易控制(仅有1例患者死于急性GVHD)。本组病例重度急性GVHD发生率较低可能与以下因素有关:①预处理方案中足量ATG在体内持续去除T淋巴细胞,起到预防GVHD的作用且不增加复发率[27]–[28]。②我们在传统的GVHD预防方案基础上加用2次抗CD25单抗。抗CD25单抗可阻断活化的IL-2受体,在T细胞克隆增殖前抑制IL-2介导的T淋巴细胞活化与增殖,不仅对淋巴细胞具有较高的亲和性且药物半衰期较长,其阻断IL-2受体的时间可长达30~45 d[29]。近期研究表明抗CD25单抗并不增加恶性肿瘤的复发和移植后感染[30],故抗CD25单抗和传统预防GVHD方案联合应用可能是非常好的GVHD预防方案。③研究显示G-CSF可使供者Th1细胞向Th2细胞转化、移植T细胞功能从而减弱急性GVHD的严重程度[31],但由于我们输注的供者MNC中含有非常高的T细胞,故我们在+1 d~+15 d常规加用地塞米松5 mg/d,+16 d~+30 d很快减完,可能也起到降低重度急性GVHD的作用;④有研究表明输注超高剂量单倍体相合CD34+细胞可促使异体反应性T淋巴细胞产生凋亡,促进造血干细胞植入、减轻GVHD[32]–[33]。⑤RIC预处理明显减轻了患者组织和器官的损伤,早期诊断急性GVHD并积极干预可能也是本组患者重度急性GVHD发生率较低的原因。

慢性GVHD是allo-HSCT的一个主要并发症,也是影响移植后生活质量的重要因素。本组患者慢性GVHD发生率与文献[34]报道相似,均为局限型,未出现因慢性GVHD死亡病例,可能与加强的GVHD预防有关。

Blaise等[3]将139例行亲缘全相合造血干细胞移植的血液肿瘤患者根据RIC方案随机分为Flu+Bu+ATG组、Flu+TBI组,1年OS率分别为75%、74%,1年DFS率分别为68%、51%;Flu+Bu+ATG组的1年累积复发率为14%,1年NRM为17%。在另一项研究中,34例AML/MDS患者行全相合allo-HSCT,采用Flu+Bu的减低剂量预处理方案,1年OS、DFS率分别为56%、50%,累积复发率为21%,NRM为24%[4]。本组病例1年OS、DFS率分别为83.0%(95%CI 74.0%~92.0%)、76.5%(95%CI 66.2%~86.8%),1年累积复发率为17.5%(95%CI 8.3%~26.7%),1年NRM为12.5%(95%CI 4.2%~20.8%),显示RIC-haplo-PBSCT模式的疗效和同胞全相合移植相似。

综上,本组病例结果初步显示本中心RIC-haplo-PBSCT模式对于50岁以上恶性血液肿瘤患者具有较好的疗效。上述结果尚需大样本、多中心临床研究进一步验证。

Funding Statement

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(81660032)

Fund program: National Natural Science Foundation of China(81660032)

References

- 1.Giralt S, Estey E, Albitar M, et al. Engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic progenitor cells with purine analog-containing chemotherapy: harnessing graft-versus-leukemia without myeloablative therapy[J] Blood. 1997;89(12):4531–4536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases[J] Blood. 1998;91(3):756–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaise D, Tabrizi R, Boher JM, et al. Randomized study of 2 reduced-intensity conditioning strategies for human leukocyte antigen-matched, related allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: prospective clinical and socioeconomic evaluation[J] Cancer. 2013;119(3):602–611. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Jawahri A, Li S, Ballen KK, et al. Phase II trial of reduced-intensity busulfan/clofarabine conditioning with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, and acute lymphoid leukemia[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(1):80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gratwohl A, Hermans J, Goldman JM, et al. Risk assessment for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia before allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation. Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation[J] Lancet. 1998;352(9134):1087–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohty M, Jacot W, Faucher C, et al. Infectious complications following allogeneic HLA-identical sibling transplantation with antithymocyte globulin-based reduced intensity preparative regimen[J] Leukemia. 2003;17(11):2168–2177. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Bourgeois A, Lestang E, Guillaume T, et al. Prognostic impact of immune status and hematopoietic recovery before and after fludarabine, IV busulfan, and antithymocyte globulins (FB2 regimen) reduced-intensity conditioning regimen (RIC) allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT)[J] Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(3):177–186. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oudin C, Chevallier P, Furst S, et al. Reduced-toxicity conditioning prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation improves outcome in patients with myeloid malignancies[J] Haematologica. 2014;99(11):1762–1768. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.105981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lown RN, Shaw BE. Beating the odds: factors implicated in the speed and availability of unrelated haematopoietic cell donor provision[J] Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(2):210–219. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, et al. Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse[J] J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3447–3454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang XJ, Liu DH, Liu KY, et al. Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without in vitro T-cell depletion for the treatment of hematological malignancies[J] Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(4):291–297. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gayoso J, Balsalobre P, Kwon M, et al. Busulfan based myeloablative conditioning regimens for haploidentical transplantation in high risk acute leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes[J] Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(3):332–339. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ichinohe T, Uchiyama T, Shimazaki C, et al. Feasibility of HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation between noninherited maternal antigen (NIMA)-mismatched family members linked with long-term fetomaternal microchimerism[J] Blood. 2004;104(12):3821–3828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KH, Lee JH, Lee JH, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation from an HLA-mismatched familial donor is feasible without ex vivo-T cell depletion after reduced-intensity conditioning with busulfan, fludarabine, and antithymocyte globulin[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(1):61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raj K, Pagliuca A, Bradstock K, et al. Peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation of hematological diseases from related, haploidentical donors after reduced-intensity conditioning[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(6):890–895. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niederwieser D, Maris M, Shizuru JA, et al. Low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) and fludarabine followed by hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors and postgrafting immunosuppression with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can induce durable complete chimerism and sustained remissions in patients with hematological diseases[J] Blood. 2003;101(4):1620–1629. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.袁 海龙, 江 明, 温 丙昭, et al. HLA单倍体相合与全相合外周血造血干细胞移植治疗恶性血液病的疗效比较[J] 中华器官移植杂志. 2010;31(2):79–83. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1785.2010.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.薛 文婧, 江 明, 田 猛, et al. 亲缘HLA单倍体相合非体外去T细胞外周血造血干细胞移植后急性移植物抗宿主病的临床特征及危险因素分析[J] 中华血液学杂志. 2014;35(12):1100–1106. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.杨 廷, 江 明. 减低剂量预处理方案在亲缘HLA单倍体相合造血干细胞移植中的应用[J] 中国组织工程研究. 2015;19(6):955–958. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khouri IF, Keating M, Körbling M, et al. Transplant-lite: induction of graft-versus-malignancy using fludarabine-based nonablative chemotherapy and allogeneic blood progenitor-cell transplantation as treatment for lymphoid malignancies[J] J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(8):2817–2824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carella AM, Lerma E, Dejana A, et al. Engraftment of HLA-matched sibling hematopoietic stem cells after immunosuppressive conditioning regimen in patients with hematologic neoplasias[J] Haematologica. 1998;83(10):904–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luznik Leo, O'Donnell Paul V, Heather J, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide[J] Biol Blood and Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasamon YL, Luznik L, Leffell MS, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide: effect of HLA disparity on outcome[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(4):482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto C, Ogawa H, Fukuda T, et al. Impact of a low CD34+ cell dose on allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(4):708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reisner Y, Martelli MF. From ‘megadose’ haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplants in acute leukemia to tolerance induction in organ transplantation[J] Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2008;40(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Czerw T, Labopin M, Schmid C, et al. High CD3+ and CD34+ peripheral blood stem cell grafts content is associated with increased risk of graft-versus-host disease without beneficial effect on disease control after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation from matched unrelated donors for acute myeloid leukemia - an analysis from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation[J] Oncotarget. 2016;7(19):27255–27266. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ballen KK, Koreth J, Chen YB, et al. Selection of optimal alternative graft source: mismatched unrelated donor, umbilical cord blood, or haploidentical transplant[J] Blood. 2012;119(9):1972–1980. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-354563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kröger N, Zabelina T, Binder T, et al. HLA-mismatched unrelated donors as an alternative graft source for allogeneic stem cell transplantation after antithymocyte globulin-containing conditioning regimen[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(4):454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovarik J, Wolf P, Cisterne JM, et al. Disposition of basiliximab, an interleukin-2 receptor monoclonal antibody, in recipients of mismatched cadaver renal allografts[J] Transplantation. 1997;64(12):1701–1705. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martín-Mateos RM, Graus J, Albillos A, et al. Initial immunosuppression with or without basiliximab: a comparative study[J] Transplant Proc. 2012;44(9):2570–2572. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.09.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jun HX, Jun CY, Yu ZX. A direct comparison of immunological characteristics of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF)-primed bone marrow grafts and G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood grafts[J] Haematologica. 2005;90(5):715–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quellmann S, Schwarzer G, Hübel K, et al. Corticosteroids for preventing graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic myeloablative stem cell transplantation[J] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD004885. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004885.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izumi N, Furukawa T, Sato N, et al. Risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: retrospective analysis of 73 patients who received cyclosporin A[J] Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40(9):875–880. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin PJ, Lee SJ, Przepiorka D, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: VI. The 2014 Clinical Trial Design Working Group Report[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(8):1343–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]