Abstract

目的

了解中国血液病患者中性粒细胞缺乏(粒缺)伴发热的发生率、临床和微生物学特征及危险因素。

方法

前瞻性研究2014年10月20日至2015年3月20日来自全国11家血液病中心发生粒缺伴发热的连续血液病患者发热情况及危险性因素。

结果

1 139例患者共发生784例次粒缺伴发热,粒缺持续21 d时发热的累积发生率为81.9%。多因素分析显示中心静脉置管(P<0.001,HR= 3.407,95% CI 2.276~4.496)、胃肠道黏膜炎(P<0.001,HR=10.548, 95% CI 3.245~28.576)、既往90 d内暴露于广谱抗生素(P<0.001,HR=3.582,95% CI 2.387~5.770)和粒缺持续时间>7 d(P<0.001,HR= 4.194,95% CI 2.572~5.618)是粒缺伴发热的危险因素。无任何危险因素、具备1项、2项、3~4项危险因素患者发热的累计发生率依次增加(35.4%、69.2%、86.1%及95.6%,P<0.001)。784例次粒缺伴发热中,不明原因发热253例次(32.3%),临床证实的感染429例次(54.7%),微生物学证实的感染102例次(13.0%)。最常见的感染部位依次为肺(388例次,49.5%)、上呼吸道(159例次,16.0%)、肛周组织(77例次,9.8%)、血流(60例次,7.7%)。最常见的病原菌为革兰阴性菌(44.54%),其次为革兰阳性菌(37.99%)和真菌(17.47%)。发热与未发热患者相比,两组之间总体病死率差异无统计学意义(9.2%对4.8%,P=0.099)。多因素分析显示年龄>40岁(P=0.047,HR=5.000,95% CI 0.853~28.013)、血流动力学不稳(P=0.001,HR=13.185, 95% CI 2.983~54.915)、既往耐药菌的定植或感染(P=0.005,HR=28.734,95% CI 2.921~313.744)、血流感染(P=0.038,HR=9.715, 95% CI 1.110~81.969)和肺部感染(P=0.031,HR=25.905, 95% CI 1.381~507.006)是与总体死亡相关的危险因素。

结论

发热是血液病患者粒缺期常见的合并症,不同部位的感染有不同的致病菌谱。粒缺持续时间>7 d、中心静脉置管、胃肠道黏膜炎和既往90 d内暴露于广谱抗生素是粒缺伴发热发生的危险因素。

Keywords: 发热, 中性粒细胞减少, 血液病

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the incidence, clinical and microbiological features of febrile, and risk factors during neutropenia periods in patients with hematological diseases.

Methods

From October 20, 2014 to March 20, 2015, consecutive patients who had hematological diseases and developed neutropenia during hospitalization were enrolled in the prospective, multicenter and observational study.

Results

A total of 784 episodes of febrile occurred in 1 139 neutropenic patients with hematological diseases. The cumulative incidence of febrile was 81.9% at 21 days after neutropenia. Multivariate analysis suggested that central venous catheterization (P<0.001, HR=3.407, 95% CI 2.276–4.496), gastrointestinal mucositis (P<0.001, HR=10.548, 95% CI 3.245–28.576), previous exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics within 90 days (P<0.001, HR=3.582, 95% CI 2.387–5.770) and duration of neutropenia >7 days (P<0.001,HR=4.194, 95% CI 2.572–5.618) were correlated with higher incidence of febrile during neutropenia. With the increase of the risk factors, the incidence of febrile increased gradually (35.4%, 69.2%, 86.1%, 95.6%, P<0.001). Of 784 febrile cases, 253 (32.3%) were unknown origin, 429 (54.7%) of clinical documented infections and 102(13.0%) of microbiological documented infections. The most common sites of infection were pulmonary (49.5%), upper respiratory (16.0%), crissum (9.8%), blood stream (7.7%). The most common pathogens were gram-negative bacteria (44.54%), followed by gram-positive bacteria (37.99%) and fungi (17.47%). There was no significant difference in mortality rates between cases with febrile and cases without febrile (9.2% vs 4.8%, P=0.099). Multivariate analysis also suggested that >40 years old (P=0.047, HR=5.000, 95% CI 0.853–28.013), hemodynamic instability (P=0.001, HR=13.185, 95% CI 2.983–54.915), prior colonization or infection by resistant pathogens (P=0.005, HR=28.734, 95% CI 2.921–313.744), blood stream infection (P=0.038, HR=9.715, 95% CI 1.110–81.969) and pulmonary infection (P=0.031, HR=25.905, 95% CI 1.381–507.006) were correlated with higher mortality rate in cases with febrile.

Conclusion

Febrile was the common complication during neutropenia periods in patients with hematological disease. There was different distribution of organisms in different sites of infection. Moreove, the duration of neutropenia >7 days, central venous catheterization, gastrointestinal mucositis and previous exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics within 90 days were the risk factors for the higher incidence of febrile.

Keywords: Fever, Neutropenia, Hematologic diseases

中性粒细胞缺乏(粒缺)伴发热是血液病患者化疗或造血干细胞移植(HSCT)后常见的合并症。国外文献报道,接受≥1个疗程化疗的造血系统恶性肿瘤患者粒缺伴发热的发生率>80%[1],相关病死率高达10%~20%[2]–[6]。相关研究显示及时给予恰当的初始经验性抗感染治疗可以改善患者预后,降低病死率[7]–[8]。而恰当的初始经验性抗感染治疗的选择需要参考患者的临床特征、致病微生物的流行病学资料、耐药情况以及抗感染药物的临床应用资料[9]。目前国内仍然缺乏针对血液病患者粒缺伴发热的流行病学资料,因此本研究我们调查并分析了中国血液病患者粒缺伴发热的流行病学特征,旨在为血液病患者粒缺伴发热的诊治提供依据。

病例与方法

1.研究设计:本研究是由全国11家血液病中心参与的一项多中心、前瞻性、观察性研究。研究时间自2014年10月20日至2015年3月20日。患者纳入标准:①罹患血液病;②住院期间至少发生1次粒缺。研究设计及项目执行均符合赫尔辛基宣言,研究方案经北京大学人民医院伦理委员会批准,所有患者均签署了知情同意书。

2.研究方案及数据收集:所有患者的资料采集均由“中国粒细胞缺乏伴发热流行病调查数据库”完成,通过临床试验观察表(CRF表)收集资料,记录项目包括患者一般特点、诊断、治疗方法、危险因素、临床特征、微生物学特征、抗感染治疗方案及生存情况。本研究为观察性研究,所有患者的诊治均由临床医生判断,并按照临床常规处理方案执行。同一患者住院期间发生多次粒缺,则被记录为多个例次;同一患者于粒缺期内发生多次发热,亦被记录为多个例次。如果患者于粒缺期内未出现发热,则随访至中性粒细胞绝对计数(ANC)≥0.5×109/L;如果患者于粒缺期内出现发热,则随访至抗感染治疗结束或患者死亡。

3.定义:粒缺定义为ANC<0.5×109/L或预计未来48 h内ANC<0.5×109/L[10]。发热定义为单次腋窝温度≥38.3 °C或腋窝温度≥38.0 °C持续1 h。参照文献[11],将发热进一步分为不明原因发热(FUO)、临床证实的感染(CDI)和微生物学证实的感染(MDI)。

4.统计学处理:采用SPSS 13.0和R软件进行统计分析。临床特征的概括主要采用描述性统计学方法;连续变量的组间比较采用Mann-Whitney检验;分类变量的组间比较采用χ2检验;连续变量阈值的确定采用ROC曲线计算;多因素分析采用Cox回归分析;发热的累积发生率采用R软件进行计算;死亡分析采用Kaplan-Meier曲线法描述,并应用Logrank检验进行组间比较。所有比较均为双侧检验,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果

1.病例:共入组患者1 139例,中位年龄38(3~83)岁,126例(11.1%)年龄<18岁,677例(59.4%)为男性。常见的血液病类型依次为急性髓系白血病(52.1%)、急性淋巴细胞白血病(27.4%)、非霍奇金淋巴瘤(NHL)(9.2%)和骨髓增生异常综合征(MDS)(4.4%),随后依次为多发性骨髓瘤(MM)(3.4%)、重型再生障碍性贫血(SAA)(2.2%)、慢性髓性白血病(CML)(0.8%)和霍奇金淋巴瘤(HL)(0.5%)。全部1 139例患者中,823例(72.3%)接受了化疗,302例(26.5%)接受了HSCT,14例(1.2%)接受了抗人胸腺细胞球蛋白(ATG)治疗。264例(23.2%)患者有其他合并症,包括心血管疾病(72.0%)、既往肺部感染(6.0%)、糖尿病(5.7%)、携带HBV(5.4%)、既往实体肿瘤病史(1.1%)、脑血管病(1.0%)、肾功能不全(1.0%)、消化性溃疡(0.9%)和慢性阻塞性肺疾病(0.1%)。在随访期内,粒缺中位持续时间为14(3~97) d,其中76.2%的患者为极重度粒缺(ANC <0.1×109/L)。

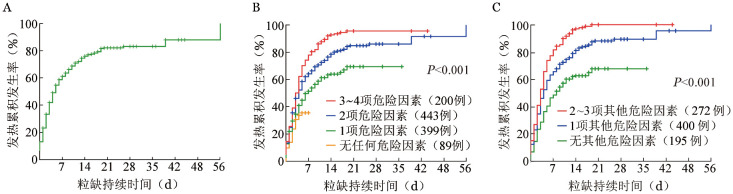

2.粒缺伴发热的发生率和危险因素:1 139例患者共出现784例次发热。粒缺持续7、14、21、28、35、42、56 d发热的累积发生率分别为60.9%、75.8%、81.9%、83.0%、83.0%、87.8%及99.7%(图1A)。不同类型血液病患者粒缺伴发热的累积发生率明显不同(急性白血病93.2%,CML 82.3%,NHL 81.3%,MDS 79.4%,SAA 64.2%,HL 66.7%,MM 63.5%),急性白血病、CML、NHL及MDS患者粒缺伴发热的累积发生率明显高于SAA、HL、MM患者(P< 0.001),且粒缺期更长(14 d对8 d,P=0.003)。接受化疗的患者粒缺伴发热的累积发生率明显高于接受HSCT及接受ATG治疗(分别为91.0%、83.6%和54.5%,P=0.006)。

图1. 1 139例血液病患者中性粒细胞缺乏(粒缺)伴发热的累积发生率分析.

A:总体情况;B:具备不同数量危险因素患者分层比较(排除8例无相关危险因素记录患者);C:867例粒缺持续时间>7 d的患者中,具备不同数量其他危险因素患者分层比较。危险因素包括中心静脉置管、胃肠道黏膜炎、既往90 d内暴露于广谱抗生素、粒缺持续时间>7 d

多因素分析显示中心静脉置管(P<0.001,HR= 3.407,95% CI 2.276~4.496)、胃肠道黏膜炎(P< 0.001,HR=10.548, 95% CI 3.245~28.576)、既往90 d内暴露于广谱抗生素(P<0.001,HR=3.582, 95% CI 2.387~5.770)和粒缺持续时间>7 d(P<0.001,HR= 4.194, 95% CI 2.572~5.618)是粒缺伴发热的独立危险因素。基于上述危险因素,我们对入组的患者进行了再次分层,排除8例无相关危险因素记录患者,将1 131例患者分为4组:无任何危险因素(89例)、具备1项危险因素(399例)、具备2项危险因素(443例)和具备3~4项危险因素(200例)。4组患者粒缺持续28 d发热的累积发生率分别为35.4%、69.2%、86.1%和95.6%(P<0.001)(图1B)。进一步根据具备其他危险因素数量对粒缺持续时间>7 d的患者进行再分组,具备其他危险因素数量的增加也会增加发热的累积发生率(不具备其他危险因素:64.5%,具备1项其他危险因素:85.4%,具备2~3项其他危险因素:95.5%;P<0.001)(图1C)。

3.粒缺伴发热的临床和微生物学特征:粒缺伴发热784例次,其中FUO 253例次(32.3%),CDI 429例次(54.7%),MDI 102例次(13.0%)。最常见的感染部位依次为肺(388例次,49.5%)、上呼吸道(159例次,16.0%)、肛周组织(77例次,9.8%)、血流(60例次,7.7%)。

从784例次粒缺伴发热中共收集了1 117份标本,其中分离出229株致病菌(20.5%),革兰阴性菌102株(44.54%),革兰阳性菌87株(37.99%),真菌40株(17.47%)(表1)。大肠埃希菌(11.36%)和肺炎克雷伯菌(11.36%)是最常见的革兰阴性菌,随后为铜绿假单胞菌(9.17%);表皮葡萄球菌(10.04%)是最常见的革兰阳性菌;白色念珠菌(11.36%)是最常见的真菌,其次为黄曲霉菌(2.62%)(表1)。此外,不同感染部位,病原菌的分布情况也明显不同:血流感染主要以大肠埃希菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、表皮葡萄球菌、铜绿假单胞菌和白色念珠菌为主,而肺部感染主要以嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌、铜绿假单胞菌、黄曲霉菌和鲍曼不动杆菌为主(表1)。在本研究中,产超广谱β内酰胺酶(ESBL)的大肠埃希菌的检出率为81.8%,产ESBL的肺炎克雷伯菌的检出率为47.3%,未检出耐万古霉素的肠球菌或葡萄球菌。

表1. 229株致病微生物分布特征[株数(%)].

| 组别 | 痰 | 血流 | 导管尖端 | 粪便 | 尿液 | 脓性分泌物 | 无菌体液 | 肛周拭子 | 合计 |

| 革兰阴性菌 | 36(15.72) | 57(24.89) | 1(0.44) | 0 | 1(0.44) | 2(0.87) | 0 | 5(2.18) | 102(44.54) |

| 大肠埃希菌 | 2(0.87) | 22(9.61) | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 26(11.36) |

| 肺炎克雷伯菌 | 4(1.75) | 19(8.30) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 0 | 2(0.87) | 26(11.36) |

| 肠杆菌 | 1(0.44) | 1(0.44) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2(0.87) |

| 嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌 | 6(2.62) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6(2.62) |

| 锏绿假单胞菌 | 10(4.37) | 8(3.49) | 1(0.44) | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 0 | 1(0.44) | 21(9.17) |

| 鲍曼不动杆菌 | 5(2.18) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5(2.18) |

| 其他 | 8(3.49) | 7(3.06) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 16(6.99) |

| 革兰阳性菌 | 24(10.48) | 38(16.59) | 4(1.75) | 0 | 2(0.87) | 2(0.87) | 1(0.44) | 16(6.99) | 87(37.99) |

| 表皮葡萄球菌 | 5(2.18) | 12(5.24) | 4(1.75) | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 1(0.44) | 0 | 23(10.04) |

| 金黄色葡萄球菌 | 4(1.75) | 3(1.31) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 0 | 0 | 8(3.49) |

| 凝固酶阴性的葡萄球菌 | 3(1.31) | 4(1.75) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7(3.06) |

| 溶血性葡萄球菌 | 1(0.44) | 2(0.87) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 4(1.75) |

| 粪肠球菌 | 1(0.44) | 4(1.75) | 0 | 0 | 2(0.87) | 0 | 0 | 6(2.62) | 13(5.68) |

| 屎肠球菌 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8(3.49) | 8(3.49) |

| 肺炎链球菌 | 2(0.87) | 1(0.44) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3(1.31) |

| 草绿色链球菌 | 6(2.62) | 3(1.31) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9(3.98) |

| 其他 | 2(0.87) | 9(3.98) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 12(5.24) |

| 真菌 | 13(5.68) | 9(3.98) | 0 | 18(7.86) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40(17.47) |

| 黄曲霉菌 | 6(2.62) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6(2.62) |

| 烟曲霉菌 | 1(0.44) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) |

| 白色念珠菌 | 6(2.62) | 5(2.18) | 0 | 15(6.55) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26(11.36) |

| 热带念珠菌 | 0 | 3(1.31) | 0 | 3(1.31) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6(2.62) |

| 隐球菌 | 0 | 1(0.44) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(0.44) |

| 合计 | 73(32.30) | 104(45.41) | 5(2.18) | 18(7.86) | 3(1.31) | 4(1.75) | 1(0.44) | 21(9.17) | 229(100.0) |

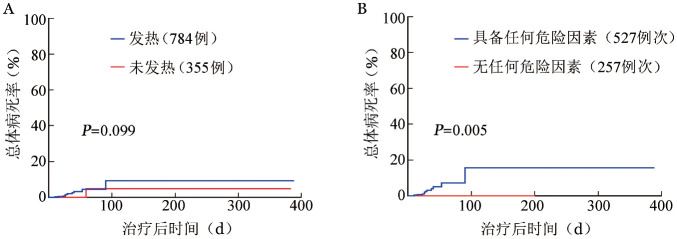

4.粒缺伴发热患者的病死率及死亡相关危险因素:发热与未发热患者总体病死率比较,差异无统计学意义(9.2%对4.8%,P=0.099)(图2A)。其中,肺部感染病死率最高(20.8%),血流感染病死率为7.1%。此外,在784例次粒缺伴发热患者中,多因素分析显示年龄>40岁(P=0.047,HR=5.000, 95% CI 0.853~28.013)、血流动力学不稳(P=0.001,HR= 13.185, 95% CI 2.983~54.915)、既往耐药菌的定植或感染(P=0.005,HR=28.734,95% CI 2.921~313.744)、血流感染(P=0.038,HR=9.715, 95% CI 1.110~81.969)和肺部感染(P=0.031,HR=25.905,95% CI 1.381~507.006)是与总体死亡相关的独立危险因素。具备以上任意危险因素的患者(527例)总体病死率明显高于无以上危险因素的患者(257例)(15.6%对0,P=0.005)(图2B)。

图2. 1 139例中性粒细胞缺乏血液病患者死亡情况分析.

A:发热和未发热患者比较;B:784例次发热患者中,无任何危险因素和具备任何危险因素比较(危险因素包括年龄>40岁、血流动力学不稳、既往有耐药菌定植或感染、血流感染及肺部感染)

讨论

首先,本研究我们发现发热是血液病患者粒缺期常见的合并症,粒缺持续21 d时发热的累积发生率高达81.9%。除了粒缺持续时间>7 d之外,胃肠道黏膜炎、中心静脉置管和既往90 d内暴露于广谱抗生素均为粒缺伴发热发生的危险因素。一些研究表明中心静脉置管可以破坏皮肤完整性,为病原菌的定植提供了场所,而既往广谱抗生素的应用又与耐药菌的定植和感染有关[12]–[14]。此外,HSCT后10 d严重的黏膜炎与HSCT后早期发热密切相关(P=0.03)[15],可能与化疗或HSCT前的预处理方案导致胃肠道黏膜屏障破坏,肠道定植的正常菌群跨越损坏的黏膜屏障易位进入血流相关。更进一步,在上述这些危险因素的基础上,我们对处于粒缺期的患者进行了再分层,随着危险因素数量的增加,发热的累积发生率也随之增加。即使是在粒缺持续时间>7 d的患者中,其他危险因素的增加也会使发热的发生率逐渐增加。因此,即使是对于那些预计粒缺持续时间>7 d的患者,基于胃肠道黏膜炎、中心静脉置管和既往广谱抗生素的应用这3个危险因素也可以对患者进行进一步的分层,并筛选出高危患者(即具备上述3个危险因素中的任意1个)。对于高危患者,应该抢先给予抗生素预防治疗,以便降低感染风险;而对于低危患者,应该避免使用抗生素预防治疗,以便降低耐药菌定植的出现。

其次,我们发现在罹患急性白血病、CML、NHL或MDS的患者中,粒缺伴发热的发生率明显高于罹患SAA、HL或MM的患者(P<0.001)。Castagnola等[16]也发现接受强烈化疗的急性白血病或NHL患者、接受异基因HSCT和接受自体HSCT的患者往往有更高的发热风险(RR分别为1.18、1.02和1.13),但接受维持治疗的患者发热风险较低(RR=0.12)。而且,我们还发现与罹患SAA、HL或MM的患者相比,罹患急性白血病、CML、NHL或MDS患者有更长的粒缺期(14 d对8 d,P=0.003),而粒缺持续时间>7 d是发热发生的危险因素。不同疾病间的差异可能是因为罹患急性白血病、CML、MDS或NHL的患者往往接受了更强烈的治疗,如强大的化疗或HSCT,导致更长时间的粒缺,最终引起更高的发热发生率。

第三,本组接受HSCT的患者发热的累积发生率低于接受化疗的患者(83.6%对91.0%),可能与肠道除菌剂的应用和入住层流病房有关。Cordonnier等[17]发现未应用肠道除菌剂与更高的革兰阴性菌感染风险相关(P=0.001)。这可能与化疗和HSCT前的预处理方案导致胃肠道黏膜屏障被破坏,随后肠道定植的菌群跨越黏膜屏障,最终易位进入血流引起感染有关。而肠道除菌剂可以抑制肠道定植菌落的生长,并降低肠道菌落易位进入血流。因此,对于接受化疗和HSCT的有严重胃肠道黏膜炎的患者,肠道除菌剂的应用很可能是必需的。

第四,文献报道血液恶性肿瘤患者最常见的感染部位是呼吸道,病死率为13.6%,血流感染发生率为4.0%~8.9%,病死率为18.0%[18]–[19]。本研究中最常见的感染部位是肺(49.5%),其次为上呼吸道(16.0%)、肛周组织(9.8%)和血流(7.7%),肺部感染病死率最高,为20.8%,血流感染病死率为7.1%。此外,我们还发现,不同的感染部位其致病菌谱也有明显的不同,提示在选择初始经验性抗感染方案时,需要考虑不同感染部位的不同致病菌谱。由于血流感染和肺部感染致病菌谱不同,并且呼吸道标本中检出的嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌和鲍曼不动杆菌往往对多种抗生素耐药,并与较高的病死率相关[20]–[21]。因此,本研究中肺部感染较之血流感染有更高的病死率。

第五,我们还发现年龄>40岁、血流动力学不稳、既往有耐药菌定植或感染、血流感染及肺部感染是与总体死亡相关的独立危险因素。一些研究已经证实既往耐药菌的定植或感染是耐药菌感染的危险因素,并且通常导致较高的病死率[22]。因此,对于具备上述危险因素的患者,或许应该考虑更强的抗感染治疗,甚至可能需要根据致病菌谱分布情况覆盖耐药菌。

总之,我们发现对于处于粒缺期的血液病患者,发热是常见的合并症。中心静脉置管、胃肠道黏膜炎、既往90 d内暴露于广谱抗生素和粒缺持续时间> 7 d是发热发生的危险因素。并且,基于这些危险因素可以筛选出高危患者。对于高危患者,应该给予抗生素的预防,以便降低感染风险;而对于低危患者,应该避免抗生素预防,以便降低耐药菌定植的出现。此外,不同部位的感染有不同的致病菌谱,这也为治疗药物的选择提供了病原学的依据。

References

- 1.Klastersky J. Management of fever in neutropenic patients with different risks of complications[J] Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39 Suppl 1:S32–37. doi: 10.1086/383050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramzi J, Mohamed Z, Yosr B, et al. Predictive factors of septic shock and mortality in neutropenic patients[J] Hematology. 2007;12(6):543–548. doi: 10.1080/10245330701384237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almyroudis NG, Fuller A, Jakubowski A, et al. Pre-and postengraftment bloodstream infection rates and associated mortality in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients[J] Transpl Infect Dis. 2005;7(1):11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2005.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikulska M, Del Bono V, Raiola AM, et al. Blood stream infections in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: reemergence of Gram-negative rods and increasing antibiotic resistance[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacar S, Hacioglu SK, Keskin A, et al. Evaluation of febrile neutropenic attacks in a tertiary care medical center in Turkey[J] J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2(5):359–363. doi: 10.3855/jidc.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blennow O, Ljungman P, Sparrelid E, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of bloodstream infections during the preengraftment phase in 521 allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations[J] Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16(1):106–114. doi: 10.1111/tid.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang CI, Kim SH, Park WB, et al. Bloodstream infections caused by antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacilli: risk factors for mortality and impact of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy on outcome[J] Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(2):760–766. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.760-766.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lodise TP, Jr, Patel N, Kwa A, et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality among patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: impact of delayed appropriate antibiotic selection[J] Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(10):3510–3515. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00338-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.中华医学会血液学分会、中国医师协会血液科医师分会. 中国中性粒细胞缺乏伴发热患者抗菌药物临床应用指南[J] 中华血液学杂志. 2012;33(8):693–696. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2012.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america[J] Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):e56–93. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viscoli C, Castagnola E. Prophylaxis and empirical therapy for infection in cancer patients. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Doolin R, et al., editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases[M] Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 3442–3462. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gudiol C, Calatayud L, Garcia-Vidal C, et al. Bacteraemia due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-EC) in cancer patients: clinical features, risk factors, molecular epidemiology and outcome[J] J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(2):333–341. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudiol C, Tubau F, Calatayud L, et al. Bacteraemia due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli in cancer patients: risk factors, antibiotic therapy and outcomes[J] J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(3):657–663. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyle EP, Bilker WB, Gasink LB, et al. Impact of different methods for describing the extent of prior antibiotic exposure on the association between antibiotic use and antibiotic-resistant infection[J] Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(6):647–654. doi: 10.1086/516798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facchini L, Martino R, Ferrari A, et al. Degree of mucositis and duration of neutropenia are the major risk factors for early posttransplant febrile neutropenia and severe bacterial infections after reduced-intensity conditioning[J] Eur J Haematol. 2012;88(1):46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castagnola E, Fontana V, Caviglia I, et al. A prospective study on the epidemiology of febrile episodes during chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in children with cancer or after hemopoietic stem cell transplantation[J] Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1296–1304. doi: 10.1086/522533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordonnier C, Herbrecht R, Buzyn A, et al. Risk factors for Gram-negative bacterial infections in febrile neutropenia[J] Haematologica. 2005;90(8):1102–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.韩 冰, 邸 海侠, 周 道斌, et al. 血液科2388例次住院患者感染危险因素的分析[J] 北京医学. 2007;29(6):327–329. [Google Scholar]

- 19.林 湘珠, 马 劼, 彭 志刚, et al. 血液病患者医院感染的临床分析[J] 中华医院感染学杂志. 2010;20(23):3679–3681. [Google Scholar]

- 20.胡 付品, 朱 德妹, 汪 复, et al. 2013年中国CHINET细菌耐药性监测[J] 中国感染与化疗杂志. 2014;14(5):369–378. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metan G, Demiraslan H, Kaynar LG, et al. Factors influencing the early mortality in haematological malignancy patients with nosocomial Gram negative bacilli bacteraemia: a retrospective analysis of 154 cases[J] Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Averbuch D, Orasch C, Cordonnier C, et al. European guidelines for empirical antibacterial therapy for febrile neutropenic patients in the era of growing resistance: summary of the 2011 4th European Conference on Infections in Leukemia[J] Haematologica. 2013;98(12):1826–1835. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.091025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]