Abstract

目的

加深对先天性角化不良(dyskeratosis congenital,DC)伴骨髓衰竭的认识。

方法

收集2010年9月30日至2015年9月30日8例伴骨髓衰竭DC患儿的临床资料,利用二代测序技术对DKC1、TERC、TERT、NOP10、NHP2、TINF2等16种端粒相关基因进行全外显子及剪接位点测序分析。

结果

8例DC患儿中男6例、女2例,中位发病月龄为42(15~60)个月。初诊血常规:中位WBC 3.99(1.26~5.44)×109/L,中位中性粒细胞计数1.11(0.38~2.15)×109/L,中位RBC 2.45(0.37~3.56)×1012/L,中位HGB 82.5(15~127) g/L,中位PLT 27(2~112)×109/L。8例患儿中6例骨髓增生减低或重度减低。3例患儿检出DKC1基因突变:c.961C>A 1例,c.1058C>T 2例;4例患儿检出TINF2基因突变:c.849delC、c.844C>T、c.811C>T、c.862T>A合并c.871delA各1例;1例患儿检出TINF2基因突变(c.848C>A)合并TERT基因突变(c.1138C>T)。其中DKC c.961C>A、TINF2 c.849delC、TINF2 c.871delA突变为首次报道。7例患儿口服雄激素治疗,其中5例血常规指标改善。1例患儿死于重症感染,其余7例患儿维持治疗。

结论

DC伴骨髓衰竭以TINF2突变和DKC1突变为主。雄激素治疗对部分病例有效。

Keywords: 先天性角化不良, 骨髓衰竭, 端粒, 儿童, DNA突变分析

Abstract

Objective

To summary clinical and genetic features of childhood dyskeratosis congenital (DC) patients with bone marrow failure.

Methods

The clinical data of 8 DC patients with bone marrow failure diagnosed between September 2010 and September 2015 were collected. Whole exons with flanking regions of the 16 telomere-related genes, including DKC1, TERC, TERT, NOP10, NHP2, TINF2 and so on, were analyzed by next generation sequence.

Results

Six males and two females were included, with a median age of 42(15–60) months. The median blood cell count at onset were as follow: WBC 3.99 (1.26–5.44) × 109/L, ANC 1.11 (0.38–2.15) × 109/L, RBC 2.45 (0.37–3.56) × 1012/L, HGB 82.5(15–127) g/L, PLT 27 (2–112) ×109/L. Hypoplastic or marked hypoplastic bone marrow were seen in 6 patients. DKC1 mutiaton were indentified in 3 patients: one c.961C>A mutation, and two c.1058C>T mutation. TINF2 mutations were identified in 4 patients: c.849delC, c.844C>T, c.811C>T, c.862T>A combined c.871delA. One patient had TINF2 mutation c.848C>A combined TERT mutation c.1138C>T. DKC1 c.961C>A mutation, TINF2 c.849delC mutation and TINF2 c.871delA mutaion were not reported so far. 5 of 7 patients got better after androgen administration. During follow-up, one patient died of serious infection, the other seven patients continued the treatment.

Conclusion

TINF2 and DKC1 mutations were the main genetic phenotypes in childhood DC with marrow failure patients. Androgen is effetive in some cases.

Keywords: Dyskeratosis congenital, Bone marrow failure, Telomere, Child, DNA mutational analysis

先天性角化不良(dyskeratosis congenital,DC)是一种罕见的先天性骨髓衰竭性疾病,其特征性临床表现为异常皮肤色素沉着、指(趾)甲角化不良、口腔黏膜白斑三联征[1]。DC患者常合并骨髓衰竭、肺纤维化、肝纤维化等多系统并发症,并具有肿瘤易感性[2]。骨髓衰竭是DC患者最常见的严重并发症和主要死亡原因[3]。端粒功能异常是DC的主要发病原因[4],约60%的患者可检测到先天性角化不良基因1(dyskeratosis congenita 1,DKC1)、端粒酶RNA元件(telomerase RNA component,TERC)、端粒逆转录酶(telomerase reverse transcriptase,TERT)、端粒重复结合蛋白1作用因子2(TRF1-interacting nuclear factor 2,TINF2)等多种端粒相关基因突变[5]。现报告我中心近年来收治的8例伴骨髓衰竭DC患儿的临床特征及基因分析结果。

病例与方法

1.病例及诊断标准:2010年9月30日至2015年9月30日在我院儿童血液病诊疗中心明确诊断为DC伴骨髓衰竭的8例患儿纳入研究。参照文献[3]标准对患儿进行诊断。本研究通过中国医学科学院血液病医院伦理委员会审核。所有患儿家长均知情同意。

2.基因检测:提取患儿外周血DNA[天根生化科技(比较)有限公司TIANamp Blood DBA Kit血液基因组DNA提取试剂盒lot#M1218]。设计端粒相关的DKCl、TERC、TERT、TINF2、NOP 10(NOP 10 ribonucleoprotein)、NHP2(NHP2 ribonucleoprotein)、USB1(U6 snRNA biogenesis 1)、WRAP53(WD repeat containing, antisense to TP53)、CTC1(CTS telomere maintenance complex component 1)、端粒重复结合因子1(telomeric repeat binding factor 1, TRF1)、TRF2、TERF2IP (telomeric repeat binding factor 2 interacting protein)、端粒保护蛋白(protection of telomeres, POT1)、TINF2作用蛋白1(TIN2-interacting protein 1, TPP1)、TEN1(CST complex subunit)、OBFC1(oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding fold containing 1)共16个基因的全外显子及剪接位点目标序列捕获探针。利用美国Illumina公司HiSeq 2000测序仪进行测序并分析(由北京迈基诺基因科技有限责任公司完成)。

3.突变位点验证:提取患儿外周血DNA(方法同前),设计包含突变位点在内的引物,进行Sanger法测序(由北京迈基诺基因科技有限责任公司完成)。将测序结果与寡合苷酸多态性数据库(dbSNP)(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP)进行比对。

4.随访:每3~6个月门诊复诊评估1次,随访截至2015年9月30日。失访1例,其余7例患儿中位随访时间为18(5~52)个月。

结果

1.临床特征:8例患儿来自无血缘关系的8个家族,其中男6例,女2例,中位发病月龄为42(15~60)个月。8例患儿均存在不同程度骨髓衰竭,其中6例(例1、2、3、4、5、7)以一系或多系血细胞减少为首发表现。4例(例1、4、7、8)有典型的异常皮肤色素沉着、指(趾)甲角化不良、口腔黏膜白斑三联征表现。此外,4例患儿伴有其他系统异常:例3左心房、左心室增大;例4左眼视网膜脱落;例6阴茎发育不良;例7肺纤维化、左心房室增大伴肺动脉高压。除例1父亲为伴肺纤维化DC患者,其余7例患儿家族中均无上述症状者。8例患儿的临床特征见表1。

表1. 8例先天性角化不良伴骨髓衰竭患儿的临床特征.

| 例号 | 性别 | 发病月龄(月) | 主要临床表现 |

初诊血常规 |

骨髓增生程度a | 随访(月) | 雄激素疗效 | |||||||

| 色素沉着 | 角化不良 | 黏膜白斑 | 其他 | WBC(×109/L) | NEUT (×109/L) | HGB (g/L) | MCV(fl) | PLT(×109/L) | ||||||

| 1 | 男 | 54 | + | + | + | − | 4.14 | 0.38 | 127 | 102.0 | 59 | 减低 | 52 | 有效 |

| 2 | 男 | 52 | + | − | + | − | 3.65 | 2.15 | 98 | 96.4 | 112 | 活跃 | 1 | 有效 |

| 3 | 男 | 30 | − | − | − | 左心房、左心室增大 | 5.44 | 1.35 | 74 | 104.2 | 32 | 重度减低 | 24 | 未应用 |

| 4 | 女 | 48 | + | + | + | 左眼视网膜脱落 | 3.84 | 0.88 | 27 | 113.5 | 2 | 重度减低 | 18 | 有效 |

| 5 | 女 | 15 | − | + | − | − | 4.57 | 1.62 | 91 | 101.5 | 22 | 减低 | 19 | 无效 |

| 6 | 男 | 29 | − | + | − | 阴茎发育不良 | 2.91 | 0.49 | 69 | 111.4 | 16 | 活跃 | 18 | 有效 |

| 7 | 男 | 36 | + | + | 肺纤维化、左心房室增大伴肺动脉高压 | 1.26 | 0.51 | 15 | 121.6 | 4 | 减低 | 7 | 有效 | |

| 8 | 男 | 60 | + | + | + | − | 4.23 | 1.73 | 111 | 95.5 | 46 | 活跃 | 5 | 无效 |

注:例1父亲诊断为先天性角化不良伴肺纤维化,其他患儿家族史无特殊。+:有;−:无;a:参照文献[6]标准评价骨髓增生程度;NEUT:中性粒细胞计数;MCV:红细胞平均体积;例2失访

8例患儿中6例(例3、4、5、6、7、8)初诊时存在不同程度的粒细胞、红细胞及血小板三系减少,1例(例1)表现为粒细胞及血小板减少,1例(例2)仅有贫血表现。初诊血常规(中位数):WBC 3.99(1.26~5.44)× 109/L,中性粒细胞计数(NEUT)1.11(0.38~2.15)× 109/L,RBC 2.45(0.37~3.56)× 1012/L,HGB 82.5(15~127) g/L, PLT 27(2~112)×109/L。6例患儿(例1、3、4、5、6、7)的红细胞平均体积(MCV)大于正常。骨髓象:6例(例1、3、4、5、6、7)有核细胞增生减低或重度减低(以巨核减少为主的不同程度三系减少),骨髓小粒细胞面积<40%且以非造血细胞为主;例3偶见双核红细胞及H-J小体;例7粒系胞质内颗粒粗大,红系可见胞间桥、核出芽和H-J小体。3例(例3、4、7)行造血干祖细胞体外集落形成实验,均表现为红系爆式集落形成单位(BFU-E)、红细胞集落形成单位(CFU-E)以及粒-巨细胞集落形成单位(CFU-GM)三种克隆形成数目明显减少。

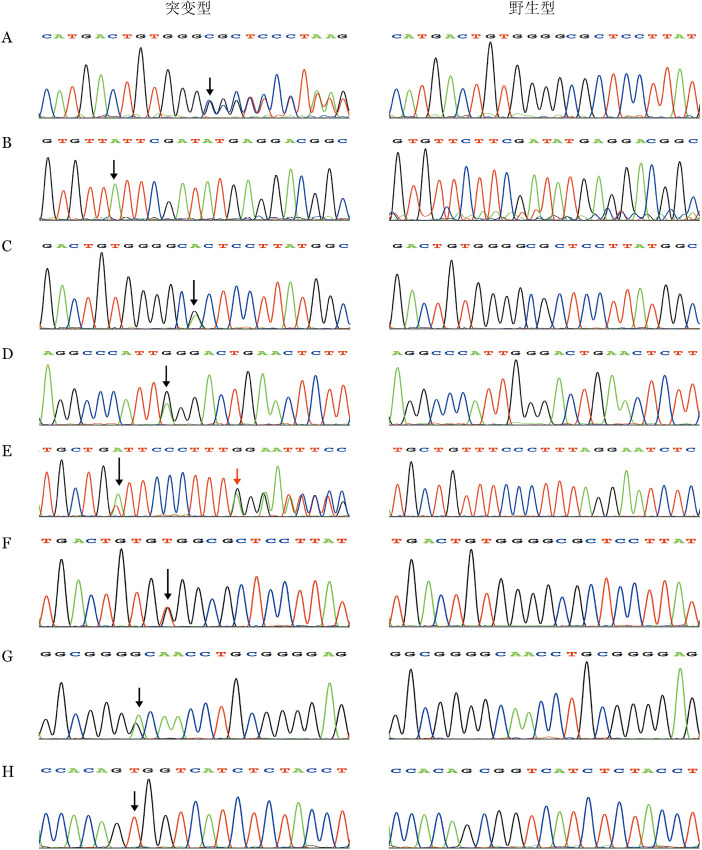

2.基因分析:8例患儿共检出位于3个基因的7种突变(表2):DKC1基因突变2种(例2、7、8),TINF2基因突变4种(例1、3、4、5),TINF2合并TERT突变1种(例6)(图1)。2种DKC1基因突变均为错义突变,其中例2为第10外显子c.961C>A突变,例7、8为第11外显子c.1058C>T突变。4种TINF2突变均发生在该基因第6外显子,其中例1为插入突变c.849delC,例3为错义突变c.844C>T,例4为终止突变c.811C>T,例5为错义突变c.862T>A合并缺失突变c.871delA。例6检出TINF2基因错义突变c.848C>A合并TERT基因错义突变c.1138C>T。DKC1 c.961C>A、TINF2 c.849delC、TINF2 c.871delA 3种突变未见文献报道。

表2. 8例先天性角化不良伴骨髓衰竭患儿端粒相关基因突变位点及遗传方式.

| 例号 | 基因 | 外显子 | 碱基改变 | 父母突变位点验证 | 首次报道者 |

| 1 | TINF2 | 外显子6 | c.849delC | 父方遗传 | 无 |

| 2 | DKC1 | 外显子10 | c.961C>A | − | 无 |

| 3 | TINF2 | 外显子6 | c.844C>T | − | Walne等[7] |

| 4 | TINF2 | 外显子6 | c.811C>T | − | Sasa等[8] |

| 5 | TINF2 | 外显子6 | c.862T>A | − | Du等[9] |

| TINF2 | 外显子6 | c.871delA | − | 无 | |

| 6 | TINF2 | 外显子6 | c.848C>A | − | Walne等[7] |

| TERT | 外显子2 | c.1138C>T | − | Hartmann等[10] | |

| 7 | DKC1 | 外显子11 | c.1058C>T | 新发突变 | Knight等[11] |

| 8 | DKC1 | 外显子11 | c.1058C>T | 母方遗传 | Knight等[11] |

注:−:未检测

图1. 8例先天性角化不良伴骨髓衰竭患儿端粒相关基因突变测序结果(箭头所示为突变位点).

A:例1 TINF2基因突变c.849delC;B:例2 DKC1基因突变c.961C>A;C:例3 TINF2基因突变c.844C>T;D:例4 TINF2基因突变c.811C>T;E:例5 TINF2基因突变c.862T>A(黑色箭头)和c.871delA(红色箭头);F:例6 TINF2基因突变c.848C>A;G:例6 TERT基因突变c.1138C>T;H:例7、8 DKC1基因突变c.1058C>T

例1、7、8患儿父母接受基因检测。例1与其确诊为DC的父亲(有三联征、肺纤维化,无骨髓衰竭)检出相同的TINF2突变;例7为新发突变,父母均无该突变;例8与母亲携带相同突变,由于DKC基因突变导致的DC为X连锁隐性遗传,该患儿母亲虽携带突变基因但为杂合子,目前表型正常。

8例DC伴骨髓衰竭患儿端粒相关基因突变位点见表2。

3.治疗及转归:8例患儿口服环孢素A治疗均无明显效果。7例患儿应用雄激素治疗,其中5例血常规指标有所改善、输血间期延长(表1),其中1例患儿(例4)指甲角化不良有所改善。

在7例完成随访的患者中,未见恶性肿瘤发生。1例(例4)发病后81个月死于重症感染。

讨论

1999年,DKC1基因的发现及其功能的研究首次阐明了DC的发病机制[12]–[13]。端粒及端粒酶功能缺陷是导致DC的主要原因。端粒是一种位于染色体末端,保持基因组完整性以及染色体稳定性的特殊结构。其由“TTAGGG”串联重复DNA序列以及端粒蛋白复合体(shelterin complex)组成。TINF2基因编码的蛋白质是构成端粒蛋白复合体的6种核心蛋白之一[14]。端粒的延长和维持所需要的端粒酶是一种核糖核蛋白,由端粒逆转录酶(TERT)、作为模板的RNA元件(TERC)以及DKC1、NOP10、NHP2等多种辅助核糖核蛋白构成[15]。上述多种基因突变在DC患者曾有报道[5]。本组8例DC患儿中DKC1基因突变3例,TINF2基因突变4例,TINF2合并TERT基因突变1例。通常DC患者骨髓衰竭发生在10~20岁[3]。本组8例患儿的中位发病月龄仅为42(15~60)个月,均有骨髓衰竭表现。本组病例TINF2基因突变具有以下特点:①TINF2基因突变集中于第6外显子,范围累及第271~291位氨基酸。其中c.849delC导致第283位氨基酸后序列移码突变以及c.871delA导致第291位氨基酸后序列移码突变为首次报道。TINF2基因各种突变类型中,错义突变在突变种类及患者数量上均占首位,缺失移码突变在TINF2基因中非常少见[7]。本研究中新发现的这两种突变均为缺失移码突变,扩展了TINF2基因突变种类。更为特殊的是,例5检出2处TINF2基因突变,例6为TINF2基因合并TERT基因突变。TERT编码端粒逆转录酶催化亚基,在DC患者中纯合突变以及杂合突变均有发现[5]。TINF2基因合并TERT基因突变未见文献报道,其意义尚需进一步研究。②本研究中TINF2基因杂合突变DC患者有早现遗传现象。例1父子检出相同的TINF2基因突变(c.849delC, p.P283fs),目前患儿父亲有三联征及肺纤维化而无骨髓衰竭发生。相对而言,携带同样突变的子代患者则很早出现DC表现及骨髓衰竭。TINF2基因杂合突变DC患者早现遗传现象罕有报道[16]。本研究3例DKC1基因突变均为错义突变,其中突变(p.A353V)在X连锁隐性DC患者中出现频率可达40%[17]。

DC临床表现异质性大,角化不良、黏膜白斑等症状也易被忽视,部分患者早期以单纯骨髓衰竭起病而无其他DC表现。本研究8例患儿中6例以血细胞减少为首发表现而无三联征等DC特征表现。端粒相关基因的突变,尤其DKC1及TINF2突变的临床阳性预测值可高达90%[5]。因此,基因检测对DC的早期确诊尤为重要。

目前,雄激素是DC患者骨髓衰竭的主要治疗药物,反应率可达70%[18]。本组8例患儿中6例服用雄激素后血细胞减少有改善或输血间隔延长,其中1例指甲角化不良有所改善。异基因造血干细胞移植可治疗DC并发的骨髓衰竭,但成功率较低,且不能治疗其他并发症[19]。针对端粒途径的靶向药物及以诱导多能干细胞技术为基础的细胞治疗为DC的治疗带来新的希望[20]–[21]。

Funding Statement

基金项目:国家重大科学研究计划(2012CB966603);卫生部2010–2012年度临床学科重点项目

Fund Program: National Basic Research Program of China(2012CB966603); Clinical Key Project of Chinese Ministry of Public Health from 2010 to 2012

References

- 1.Fernández García MS, Teruya-Feldstein J. The diagnosis and treatment of dyskeratosis congenita: a review[J] J Blood Med. 2014;5:157–167. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S47437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, et al. Cancer in dyskeratosis congenita[J] Blood. 2009;113(26):6549–6557. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita[J] Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:480–486. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballew BJ, Savage SA. Updates on the biology and management of dyskeratosis congenita and related telomere biology disorders[J] Expert Rev Hematol. 2013;6(3):327–337. doi: 10.1586/ehm.13.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dokal I, Vulliamy T, Mason P, et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Dyskeratosis congenita-update 2015[J] Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(4) doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozkaynak MF, Scribano P, Gomperts E, et al. Comparative evaluation of the bone marrow by the volumetric method, particle smears, and biopsies in pediatric disorders[J] Am J Hematol. 1988;29(3):144–147. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830290305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Beswick R, et al. TINF2 mutations result in very short telomeres: analysis of a large cohort of patients with dyskeratosis congenita and related bone marrow failure syndromes[J] Blood. 2008;112(9):3594–3600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-153445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasa GS, Ribes-Zamora A, Nelson ND, et al. Three novel truncating TINF2 mutations causing severe dyskeratosis congenita in early childhood[J] Clin Genet. 2012;81(5):470–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du HY, Mason PJ, Bessler M, et al. TINF2 mutations in children with severe aplastic anemia[J] Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(5):687. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann D, Srivastava U, Thaler M, et al. Telomerase gene mutations are associated with cirrhosis formation[J] Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1608–1617. doi: 10.1002/hep.24217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight SW, Heiss NS, Vulliamy TJ, et al. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is predominantly caused by missense mutations in the DKC1 gene[J] Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(1):50–58. doi: 10.1086/302446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell JR, Wood E, Collins K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita[J] Nature. 1999;402(6761):551–555. doi: 10.1038/990141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heiss NS, Knight SW, Vulliamy TJ, et al. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions[J] Nat Genet. 1998;19(1):32–38. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broccoli D. Function, replication and structure of the mammalian telomere[J] Cytotechnology. 2004;45(1–2):3–12. doi: 10.1007/s10616-004-5120-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez DE, Armando RG, Farina HG, et al. Telomere structure and telomerase in health and disease (review)[J] Int J Oncol. 2012;41(5):1561–1569. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savage SA, Bertuch AA. The genetics and clinical manifestations of telomere biology disorders[J] Genet Med. 2010;12(12):753–764. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f415b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vulliamy TJ, Marrone A, Knight SW, et al. Mutations in dyskeratosis congenita: their impact on telomere length and the diversity of clinical presentation[J] Blood. 2006;107(7):2680–2685. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khincha PP, Wentzensen IM, Giri N, et al. Response to androgen therapy in patients with dyskeratosis congenita[J] Br J Haematol. 2014;165(3):349–357. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gadalla SM, Sales-Bonfim C, Carreras J, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with dyskeratosis congenita[J] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(8):1238–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serravallo M, Jagdeo J, Glick SA, et al. Sirtuins in dermatology: applications for future research and therapeutics[J] Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305(4):269–282. doi: 10.1007/s00403-013-1320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal S, Loh YH, McLoughlin EM, et al. Telomere elongation in induced pluripotent stem cells from dyskeratosis congenita patients[J] Nature. 2010;464(7286):292–296. doi: 10.1038/nature08792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]