Abstract

Despite higher incidence and mortality of breast cancer among younger Black women, genetic testing outcomes remain severely understudied among Blacks. Past research on disclosure of genetic testing results to family members has disproportionately focused on White, educated, high socioeconomic status women. This study addresses this gap in knowledge by assessing (1) to whom Black women disclose genetic test results and (2) if patterns of disclosure vary based on test result (e.g., BRCA1/2 positive, negative, variant of uncertain significance [VUS]). Black women (N=149) with invasive breast cancer diagnosed age ≤50 years from 2009–2012 received free genetic testing through a prospective, population-based study. At 12 months post-testing, women reported with whom they shared their genetic test results. The exact test by binomial distribution was used to examine whether disclosure to female relatives was significantly greater than disclosure to male relatives, and logistic regression analyses tested for differences in disclosure to any female relative, any male relative, parents, siblings, children, and spouses by genetic test result. Most (77%) women disclosed their results to at least one family member. Disclosure to female relatives was significantly greater than disclosure to males (p<0.001). Compared to those who tested negative or had a VUS, BRCA1/2 positive women were significantly less likely to disclose results to their daughters (ORBRCA positive=0.25, 95% CI=0.07–0.94, p=0.041) by 12 months post-genetic testing. Genetic test result did not predict any other type of disclosure (all ps>0.12). Results suggest that in Black families, one benefit of genetic testing – to inform patients and their family with cancer risk information – is not being realized. To increase breast cancer preventive care among high-risk Black women, the oncology care team should prepare Black BRCA1/2 positive women to share genetic test results with family members and, in particular, their daughters.

Keywords: genetic counseling, genetic testing, breast cancer, BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant, disclosure, communication, disparities, family

Introduction

Despite the identification of the BRCA genes over 2 decades ago (Miki et al., 1994; Wooster et al., 1995) and the longstanding availability of testing, less than 20% of breast cancer survivors receive genetic testing for inherited breast cancer (Childers, Childers, Maggard-Gibbons, & Macinko, 2017; Drohan, Roche, Cusack, & Hughes, 2012; Kurian et al., 2017) with lower proportions among Blacks compared to non-Hispanic Whites (McCarthy et al., 2016). Once an individual is identified with a BRCA pathogenic variant, benefits of genetic testing may be magnified through sharing positive results with at-risk family members so that they too may benefit from this information, which is of tremendous importance from a public health perspective. Discussion about the importance of sharing genetic test results with family members is part of the genetic counseling session. In fact, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (M. E. Robson et al., 2015), the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (Lancaster, Powell, Chen, & Richardson, 2015), and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, along with the National Society of Genetic Counselors (Hampel, Bennett, Buchanan, Pearlman, & Wiesner, 2014)all recommend pre- and post-test genetic counseling for individuals at high risk for inherited cancer, including young breast cancer patients. Genetic counseling provides education about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and the process, risks, and benefits of genetic testing (Braithwaite, Emery, Walter, Prevost, & Sutton, 2004). Breast cancer patients who receive genetic counseling demonstrate increased knowledge about cancer genetics, more accurate perceptions of their risk, and reduced anxiety and cancer related distress (Madlensky et al., 2017; Scherr, Christie, & Vadaparampil, 2016). For patients who subsequently undergo genetic testing, another important benefit is determining whether individuals carry a germline mutation for inherited cancer risk (e.g., the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes).

If a woman tests positive for a BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant, she is encouraged to share her results with her at-risk relatives. At-risk relatives are generally considered to be any biological relative, regardless of sex. Once informed, at-risk relatives may consider their own options regarding cancer genetic counseling, genetic testing, and subsequent risk management options. Past research has shown tested individuals are likely to disclose test results to at-risk relatives (Barsevick et al., 2008; Julian-Reynier et al., 2000). In studies of majority White individuals, 91–100% of BRCA1/2 positive participants disclose genetic test results to at least one relative (Finlay et al., 2008; Julian-Reynier et al., 2000; Kegelaers, Merckx, Odeurs, van den Ende, & Blaumeiser, 2014; McGivern et al., 2004; Montgomery et al., 2013). Women are more likely to share genetic testing results with female relatives (versus male relatives) and with family members to whom they are more closely related (Montgomery et al., 2013). However, not all women who receive genetic testing disclose their results with their family, with disclosure influenced by personal, family, and psychosocial factors. For example, women who are most likely to disclose often value openness as a personality trait (Lafreniere, Bouchard, Godard, Simard, & Dorval, 2013) or feel a duty to inform their family members (Finlay et al., 2008; McGivern et al., 2004). Disclosure is also more likely in families with good support or that are more open to discussing health issues (Lafreniere et al., 2013; Montgomery et al., 2013). Disclosure may also depend on a desire for perceived control or social influence (Barsevick et al., 2008; Montgomery et al., 2013) or the perceived risk to family members (Graves et al., 2014).

However, most studies on disclosure of genetic test results have focused on educated White females of high socioeconomic status (Barsevick et al., 2008; Bradbury et al., 2012; Cheung, Olson, Tina, Han, & Beattie, 2010; Finlay et al., 2008; McGivern et al., 2004; Montgomery et al., 2013; Patenaude et al., 2006; Tercyak et al., 2013). Some minorities, particularly Black women, are less likely to be aware of genetic testing (Adams, Christopher, Williams, & Sheppard, 2015; Mai et al., 2014; Sheppard et al., 2014), be referred for genetic counseling and genetic testing (Graves et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2009; Levy et al., 2011), or discuss cancer within families (Thompson et al., 2015; Wells, Gulbas, Sanders-Thompson, Shon, & Kreuter, 2014). Despite the well-documented research on racial disparities in genetic counseling and genetic testing by our group and others (Cragun, Weidner, Kechik, & Pal, 2019; Hall & Olopade, 2006; Jones, McCarthy, Kim, & Armstrong, 2017), Black women report interest in testing with the hopes of preventing cancer and sharing information with their family members (Adams et al., 2015). Nonetheless, when Black women do receive testing, they have been found to be less likely than White women to disclose test results to family members (Cheung et al., 2010; Fehniger, Lin, Beattie, Joseph, & Kaplan, 2013). Furthermore, little is known about the timing of genetic test result disclosure among Black women. Thus, more research is needed to determine (1) to whom Black women disclose their genetic test results, and (2) whether these patterns of disclosure vary by genetic test result (e.g., BRCA1/2 positive, BRCA1/2 negative, or variant of uncertain significance [VUS]).

To fill this gap, we examined genetic test result disclosure behaviors following genetic counseling and genetic testing among Black women. As part of a larger, population-based study offering genetic testing to young Black breast cancer survivors (Pal et al., 2015), we assessed patterns of genetic test result disclosure by BRCA test result over the course of one year post-genetic testing. Consistent with prior work, we hypothesized that Black breast cancer survivors would be more likely to disclose genetic test results: (1) to female relatives (versus male relatives), and (2) if they were BRCA1/2 positive (versus BRCA1/2 negative or VUS). Exploratory analyses also examined reasons for genetic test result disclosure.

Methods

Sample

Data for the present study come from participants in a parent study, which was designed to investigate genetic and lifestyle determinants of triple negative breast cancer in premenopausal Black women. Recruitment methods have been previously published (Bonner, Cragun, Reynolds, Vadaparampil, & Pal, 2016; Pal et al., 2015) and are briefly described here. All procedures were approved by the University of South Florida (104559) and the Florida Department of Health (DOH H11168) Institutional Review Boards. Participants were eligible if they self-identified as: 1) Black women, 2) living in Florida when diagnosed with invasive breast cancer (BC), 3) diagnosed at or below age 50, 4) diagnosed between 2009–2012, 5) alive at time of recruitment, and 6) English speaking. Patients were recruited through the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS). FCDS released patient contact information and available clinical and sociodemographic information on all eligible participants. The lag time between diagnosis and availability of contact information from FCDS ranged from 6–18 months.

Patients were approached using state-mandated recruitment methods of two mailings 3 weeks apart, including a telephone response card giving women the option to decline or express interest in participation. If no response was received within 3 weeks of the second mailing, a study team member telephoned the participant. For women willing to participate, written informed consent was obtained via mail. Study participation included completion of a medical records release, study questionnaires, free genetic counseling, and saliva sample collection for DNA extraction.

Of the 1647 Black women with BC in FCDS who qualified for the parent study, we established contact with 882. Among these, 480 consented to participate (54%). Of these parent study participants, 380 (79%) also consented to participate in the current study, which entailed completing additional measures of risk management behaviors (e.g., prophylactic surgery, surveillance), psychological functioning (e.g., cancer related distress, emotional well-being), and social functioning (e.g., communication of test results) prior to genetic testing, one month following the disclosure of their genetic test results, and one year following disclosure of genetic test results. Given our focus on disclosure of genetic test results, we removed 119 participants who previously had genetic testing and 46 who chose not to receive genetic test results after testing in the current study. Of the remaining 215 participants, 149 (69%) completed the follow-up questionnaire at 1 year post-results disclosure. Thus, the final analytic sample included 149 Black breast cancer survivors.

Measures

Demographic characteristics.

Participants reported their age, relationship status, education, income, current general health, and insurance status.

Familial relationships.

Participants reported whether they had any daughters, sisters, sons, or brothers, and how many of each.

BRCA status.

After baseline assessment, participants were given free genetic counseling and genetic testing. Genetic testing included full gene sequencing and comprehensive rearrangement testing of both BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. The results were either classified as BRCA positive, BRCA negative, or a VUS.

Disclosure of genetic test results.

Participants completed a measure assessing disclosure of genetic testing results, based on the one developed by Patenaude and colleagues (2006). At 12 months post-genetic testing, participants were asked to list if they shared their results with anyone and, if so, with whom they shared. Responses were coded as yes/no for each of the following variables: any female relative, any male relative, and parents, siblings, children, and spouses.

Reasons for disclosing genetic test results.

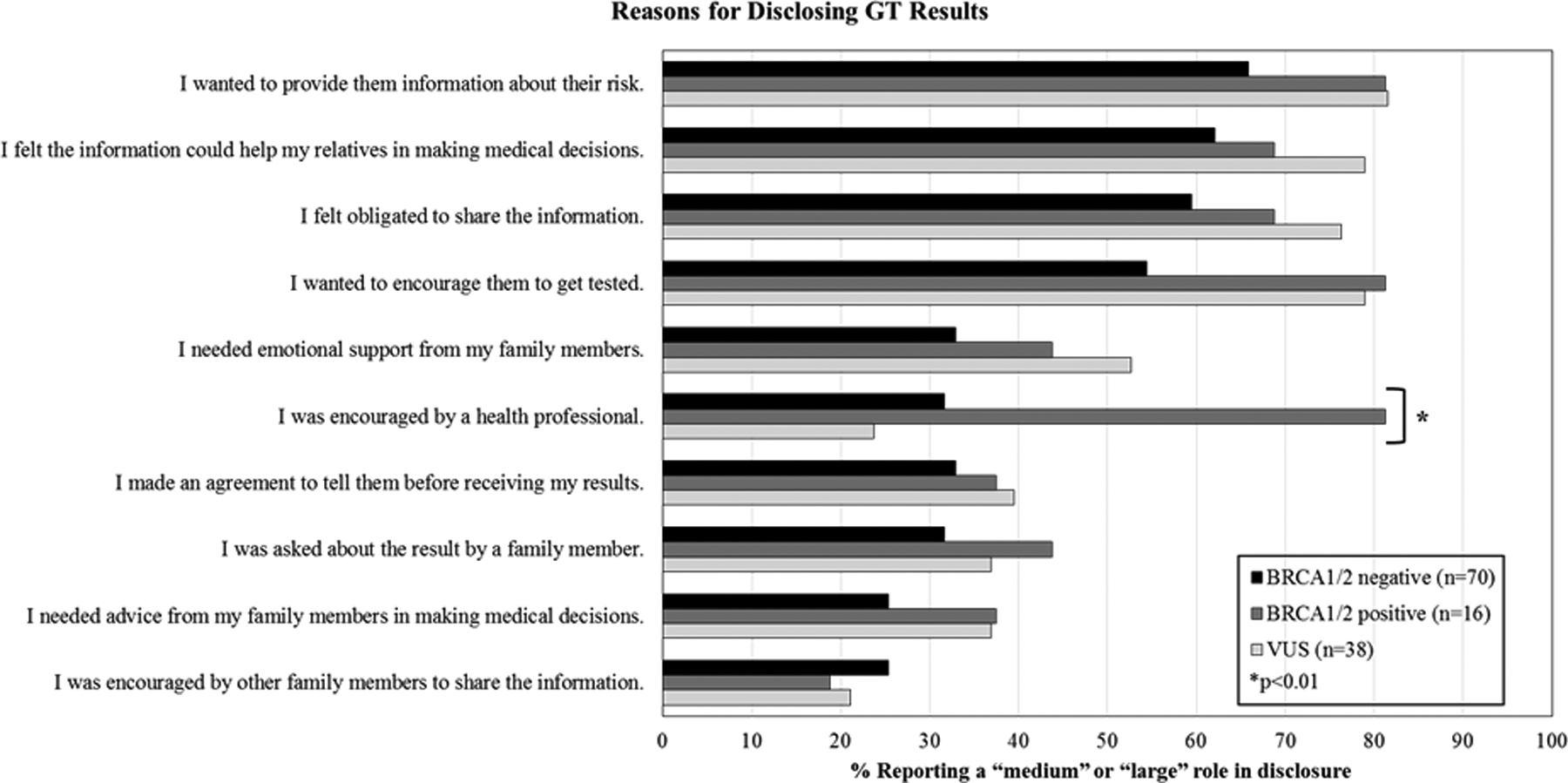

At 12 months post-genetic testing, those participants who reported sharing their results were also asked to evaluate 10 different reasons for disclosure of results, such as “I made an agreement to tell them before receiving my test results” or “I wanted to encourage them to get tested” on a 4-point scale from no role to a large role. Items for this measure were developed specifically for this project, and are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Reasons for disclosing genetic test results by BRCA1/2 status.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 25. As these analyses were exploratory in a unique sample, significance for all analyses was specified at α = 0.05 (two-tailed).

Preliminary analyses.

Chi-square tests or analyses of variance (ANOVA) determined sociodemographic differences, if any, by genetic test result (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics by BRCA1/2 status.

| Demographic Characteristics | Overall Sample (N=149) | BRCA1/2 Negative (n=85) | BRCA1/2 Positive (n=18) | VUS n=46) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current age (years): M (SD) | 44.9 (6.2) | 45.2 (5.4) | 43.8 (5.9) | 44.8 (7.8) | 0.691 |

| Relationship status (partnered): n (%) | 51 (34.2) | 28 (32.9) | 3 (16.7) | 20 (43.5) | 0.118 |

| Education: n (%) | 0.914 | ||||

| ≤12th grade/GED | 45 (30.2) | 25 (29.4) | 5 (27.8) | 15 (32.6) | |

| Vocational or some college | 44 (29.5) | 24 (28.2) | 7 (38.9) | 13 (28.3) | |

| Graduated college or higher | 59 (39.6) | 35 (41.2) | 6 (33.4) | 18 (39.1) | |

| Income: n (%) | 0.284 | ||||

| <$25,000 | 60 (40.3) | 30 (35.3) | 8 (44.4) | 22 (47.8) | |

| ≥$25,000 | 79 (53.0) | 50 (58.8) | 7 (38.9) | 22 (47.8) | |

| Insurance status (private): n (%) | 60 (40.3) | 36 (42.4) | 5 (27.8) | 19 (41.3) | 0.639 |

| Family: n (%) | |||||

| Have a sister (yes) | 113 (75.8) | 65 (76.5) | 12 (66.7) | 36 (78.3) | 0.816 |

| Have a daughter (yes) | 100 (67.1) | 54 (63.5) | 12 (66.7) | 34 (73.9) | 0.482 |

| Have a brother (yes) | 125 (84.0) | 73 (85.9) | 17 (94.4) | 35 (76.1) | 0.122 |

| Have a son (yes) | 98 (65.8) | 52 (61.2) | 11 (61.1) | 35 (76.1) | 0.145 |

Primary analyses.

Descriptive statistics were first used to describe patterns of genetic test result disclosure.

The exact test by binomial distribution tested whether disclosure to female relatives was significantly greater than disclosure to male relatives. Analyses were restricted to those participants who disclosed to either a male relative or a female relative; those who disclosed to both male and female relatives were excluded. The null hypothesis was that there is no difference between disclosure to male relatives and female relatives, which can be specified as H0: θ = 0.5 against Ha: θ ≠ 0.5. Here, θ represents the proportion of disclosure to female relatives only.

Logistic regression analyses then tested for differences in disclosure by genetic test result. In total, 10 separate logistic regression models were run, examining predictors of disclosure at 12 months to: (1) any family member, (2) any female relative, (3) any male relative, (4) her mother, (5) father, (6) daughter, (7) son, (8) sister, (9) brother, or (10) spouse. For all analyses, the participant was excluded if they did not have the particular relative we were analyzing. For significant models, sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine any differences in results with and without sociodemographic covariates (e.g., age, education, income, and insurance status).

Exploratory analyses.

Descriptive statistics were first used to examine reasons for genetic test result disclosure. Chi-square then tested for differences in reasons for disclosure by genetic test result.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

As shown in Table 1, the participants were on average 44.9 years old (SD=6.2), had a household income of at least $25,000 per year (53%), and almost half had private insurance (40%). In terms of relatives, most reported having a brother (84%), followed by a sister (76%), daughter (67%), and son (66%). No sociodemographic differences were observed between participants with negative, positive, or VUS results (all ps≥0.15).

Primary Analyses

Disclosure of test results.

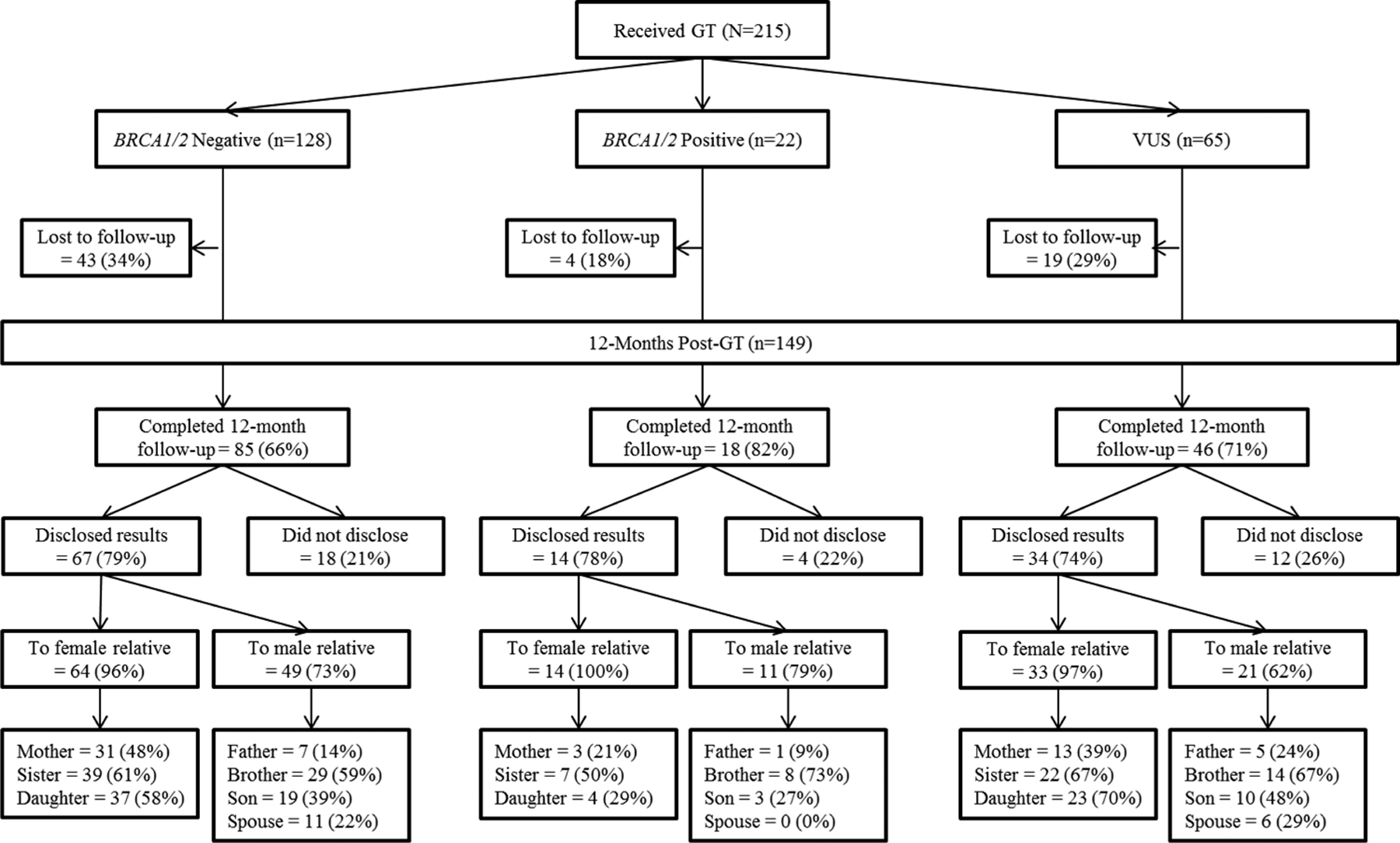

Figure 1 characterizes disclosure to first-degree relatives by genetic test result. Across groups, most (77%, n=115) participants disclosed their results to at least one family member by 12 months post-genetic testing; 34 participants disclosed to female relatives only, 4 disclosed to male relatives only, and 77 to both male and female relatives. Thus, the exact test by the binomial distribution included the 4 participants who disclosed to male family member(s) only and the 34 participants who disclosed to female family member(s) only. Rates of disclosure to female relatives was significantly greater than rates of disclosure to male relatives (p<0.001). If participants chose to disclose to a female relative, they most often disclosed their test results to a sister (61%, 68/111), followed by a daughter (58%, 64/111), and a mother (42%, 47/111). If they chose to disclose to a male relative, participants most often disclosed their test results to a brother (63%, 51/81), followed by a son (40%, 32/81), a spouse (21%, 17/81), and a father (16%, 13/81).

Figure 1.

Disclosure to relatives by genetic test result at 12 months post-genetic testing.

Disclosure by genetic test result.

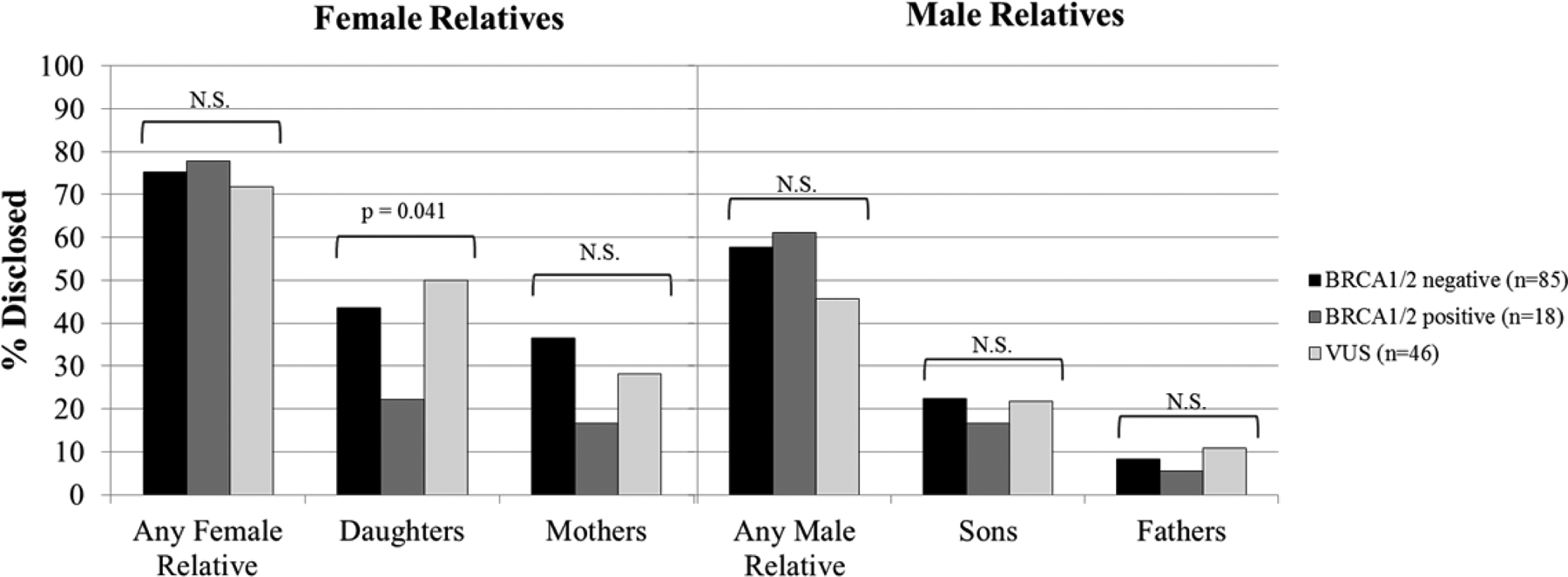

Overall patterns of disclosure to female and male relatives by genetic test result are presented in Figure 2 and Table 2. Genetic test result predicted disclosure to daughters, such that BRCA1/2 positive participants were significantly less likely to disclose genetic test results to daughters (ORBRCA positive = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.07–0.94, p=0.041). Genetic test result did not predict any other type of disclosure (all ps>0.12).

Figure 2.

Results of logistic regression analyses examining the relationship between genetic test result and disclosure to female relatives and male relatives at 12 months post-genetic testing; percentage disclosed are calculated based on the number of participants who completed the12 month follow-up assessment (N=149).

Table 2.

Results of logistic regression models examining the relationship between genetic test result and disclosure to relatives at 12 months post-genetic testing.

| Model | N | BRCA1/2 carrier status | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any family member | 149 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 0.94 | 0.28–3.21 | 0.92 | ||

| VUS | 0.76 | 0.33–1.76 | 0.52 | ||

| Any female relative | 149 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 1.15 | 0.34–3.87 | 0.82 | ||

| VUS | 0.83 | 0.37–1.87 | 0.83 | ||

| Any male relative | 149 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 1.16 | 0.41–3.27 | 0.79 | ||

| VUS | 0.62 | 0.30–1.27 | 0.19 | ||

| Mother | 149 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 0.35 | 0.09–1.30 | 0.12 | ||

| VUS | 0.69 | 0.32–1.50 | 0.34 | ||

| Father | 149 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 0.66 | 0.08–5.68 | 0.70 | ||

| VUS | 1.36 | 0.41–4.55 | 0.62 | ||

| Daughter | 100 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 0.25 | 0.07–0.94 | 0.04 | ||

| VUS | 0.92 | 0.37–2.26 | 0.85 | ||

| Son | 98 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 0.77 | 0.18–3.28 | 0.73 | ||

| VUS | 0.82 | 0.32–2.10 | 0.68 | ||

| Sister | 113 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 1.06 | 0.30–3.69 | 0.93 | ||

| VUS | 1.06 | 0.46–2.42 | 0.89 | ||

| Brother | 125 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 1.61 | 0.55–4.67 | 0.38 | ||

| VUS | 1.21 | 0.53–2.76 | 0.66 | ||

| Spouse | 51 | Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | † | † | † | ||

| VUS | 0.75 | 0.19–3.01 | 0.69 |

unable to be estimated

Sensitivity analyses were then conducted to examine whether the significant effect of genetic test result on disclosure to daughters remained significant when sociodemographic covariates were entered into the model (Table 3). In addition to genetic test result, age, education, income, and insurance status were also entered as predictors in the logistic regression model. With these variables included in the model, the effect of genetic test result was non-significant (p=0.21). However, age significantly predicted disclosure to daughters, such that older women were more likely to disclose genetic test results to daughters (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.02–1.20). None of the other sociodemographic variables predicted disclosure to daughters (all ps>0.32).

Table 3.

Results of sensitivity analyses examining the impact of including sociodemographic control variables in the logistic regression model predicting disclosure to daughters at 12 months post-genetic testing.

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1/2 carrier status | |||

| Negative | (ref) | ||

| Positive | 0.36 | 0.07–1.81 | 0.21 |

| VUS | 0.76 | 0.26–2.25 | 0.62 |

| Age (years) | 1.11 | 1.02–1.20 | 0.01 |

| Education (years) | 1.32 | 0.64–2.72 | 0.46 |

| Income | |||

| <$25,000/year | (ref) | ||

| ≥$25,000/year | 0.52 | 0.15–1.89 | 0.32 |

| Insurance Status | |||

| Non-private | (ref) | ||

| Private | 1.08 | 0.38–3.12 | 0.88 |

Exploratory Analyses

Reasons for genetic test result disclosure are presented in Figure 3. For each group (BRCA1/2 positive, BRCA1/2 negative, VUS), the most frequently endorsed reason for disclosing results with family was, “I wanted to provide them information about their risk.” Specifically, 64% of participants (n=96) reported that it played a “medium” or “large” role in the decision to disclose. Three other reasons were also frequently endorsed, regardless of genetic test result: “I felt the information could help my relatives in making medical decisions” (60%, n=90); “I felt obligated to share the information” (58%, n=87); and “I wanted to encourage them to get tested” (58%, n=86). The three least frequently endorsed reasons for disclosing were as follows: “I was encouraged by other family members to share the information” (21%, n=31); “I needed advice from my family members in making medical decisions” (n=40, 27%), and “I was asked about the result by a family member” (33%, n=49). Two participants also wrote in “other” reasons for disclosing. They were, “I love and care about them” and “Family relationship is strained”.

The only reason for genetic test result disclosure that significantly differed by BRCA1/2 status was “I was encouraged by a health professional” (p < 0.01). BRCA1/2 positive women were more likely to endorse this reason for disclosure (81%) than women who were BRCA1/2 negative (32%) or had a VUS (24%).

Discussion

This study characterizes patterns of genetic test result disclosure and family communication among Black women, who have been historically underrepresented in studies of genetic testing. In addition, this study identifies which family members either did or did not receive genetic information, when results were disclosed, and describes patterns that emerged based on types of genetic test result. This information can help inform interventions or direct specific information to provide in the course of genetic testing and counseling in a way to ensure the appropriate family members receive genetic risk information.

Our first goal was to determine to whom Black women disclose genetic test results. We found that participants more frequently disclosed genetic test results to female relatives than male relatives, a pattern that has been found elsewhere (M. B. Daly, Montgomery, Bingler, & Ruth, 2016; Dancyger et al., 2011; Montgomery et al., 2013; Patenaude et al., 2006; Wagner Costalas et al., 2003). One common facilitator of genetic test result disclosure is the belief that the information will help relatives with medical decision making (Finlay et al., 2008). It may be that participants in this study felt that female relatives could benefit from genetic test result information more than male relatives. Alternatively, disclosure to male versus female relatives may be a function of comfort. Some research demonstrates that males report significantly more difficulty discussing positive BRCA1/2 results with family members than women (Finlay et al., 2008). Although females who are BRCA1/2 positive are at significantly greater breast cancer risk than males who are BRCA1/2 positive (60–80% for females versus 1–7% for males), there are a number of critical health decisions for males (e.g., clinical breast exams, prostate cancer screening beginning at age 40, reproductive choices) that may be informed by pathogenic variant status (Tai, Domchek, Parmigiani, & Chen, 2007). In addition, males can pass a pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant to their offspring. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that men are interested in BRCA1/2 testing for themselves and their female relatives (D’Agincourt-Canning, 2001; Lodder et al., 2001; McAllister, Evans, Ormiston, & Daly, 1998; K. R. Smith, West, Croyle, & Botkin, 1999). The particularly low rates of disclosure to male relatives in this study of a Black population – 42–69% versus 59–96% in other studies of majority White populations (M. B. Daly et al., 2016; Finlay et al., 2008; Montgomery et al., 2013) – may indicate that education about and communication of the importance of BRCA1/2 for men is particularly critical for Black populations.

Our results also demonstrated large discrepancies in rate of disclosure depending on the family member. The particularly low rates of disclosure to spouses are especially notable. Chopra and Kelly (2017), who studied an Ashkenazi Jewish population, found that the highest disclosure of any test results was with spouses (at six months, 85.3% versus our 35.3% at 12 months overall). Interestingly, while only three participants with BRCA1/2 positive results were partnered, none of them shared their results with their spouse at any point during the study period. This may be because the wording of the question implied genetic family members, and we did not specifically ask about disclosure to spouses; for this reason, our ability to draw conclusions about the low disclosure rate to spouses is limited. Nonetheless, it should be noted that some women with BRCA1/2 negative and VUS results did report sharing results with their spouse, without any specific query. Thus, further research should investigate Black women’s communication of genetic test results to spouses/romantic partners.

Our second goal was to uncover patterns of disclosure based on genetic test result. We found that women with BRCA1/2 positive results were significantly less likely to disclose to their daughters at 12 months, compared to women with BRCA1/2 negative and VUS results. This contrasts with prior literature on genetic test result disclosure. Montgomery et al. (2013) found that in a study with a 95% White sample, BRCA1/2 positive participants were most likely to disclose test results with their children. Finlay et al. (2008) found high levels of disclosure in their White/Ashkenazi Jewish population, with disclosure of BRCA1/2 positive results to 94% of daughters. Daly et al. (2016) found that participants (N=312, 95% White) were significantly more likely to report BRCA1/2 positive versus BRCA1/2 negative/VUS results to their family members (Barsevick et al., 2008).

There are several reasons why women in this study may not be disclosing their positive BRCA1/2 test results with daughters. First, disclosing positive test results with family may be distressing (Wagner Costalas et al., 2003). Some BRCA1/2 positive women may choose to withhold information based on the their assessment of their relatives’ “emotional readiness” to hear about test results (Dancyger et al., 2011). Guilt about potentially passing on a harmful pathogenic variant to children is also well documented (Lynch et al., 1997; Lynch et al., 2006). Parents with hereditary breast cancer have also been shown to limit information regarding risks of prophylactic surgery and risk management information, impacting children and young people’s understanding of the impact of hereditary breast cancer (Rowland, Plumridge, Considine, & Metcalfe, 2016). However, there is a desire from children and young people for open and honest communication about genetic conditions with their parents (Rowland & Metcalfe, 2013). While communication tends to occur when there is a sense of responsibility to share information with a specific family member, this responsibility is also weighed against the potential harms of informing the individual of “bad news”, or what Gaff et al. (2007) referred to as the “calculus of responsibility”. In this population, the calculated potential harms of informing daughters of “bad news” (i.e., a positive genetic test result) may be overwhelming the “responsibility” of communicating those results.

The results of sensitivity analyses provide further insight into why participants may not disclose genetic test results to daughters. When sociodemographic covariates were included in the logistic regression model, age, rather than genetic test result, significantly predicted disclosure to daughters. Specifically, older women reported higher rates of disclosure to their daughters. The daughters of older women may themselves be older, and therefore be of appropriate age for breast cancer screening and genetic testing. Prophylactic surgery (e.g., mastectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy) and radiographic screening are generally not recommended until individuals are 25 years old (Bradbury et al., 2012; M. Robson & Offit, 2007), and cancer genetic testing is not recommended for persons under the age of 18 (Riley et al., 2012). As the belief that the information will help relatives with medical decision making is a significant motivator for genetic test result disclosure (Finlay et al., 2008), younger women in this study may be choosing to withhold this information from daughters who are not of age to utilize it; this information would not change medical management for the daughters until they are adults.

However, this study is limited in that we did not collect complete data on family composition. Data was only collected regarding family members to whom participants did disclose their results. Daughters who received genetic test results ranged in age from 7–38, while sons who received genetic test results ranged in age from 10–40. It is unknown whether participants had other, younger children from whom they had chosen to withhold genetic information. Little past research has focused on sharing of test results with minor children, but Bradbury et al. (2007) found that 49% of parents disclosed their BRCA1/2 positive genetic test results with their 25-year-old and younger children, while Patenaude et al. (2013) reported that daughters aged 18–24 had suboptimal genetic knowledge and high cancer-related distress after their mother’s testing positive for BRCA1/2.

Our exploratory analyses may shed some light on reasons for genetic test result disclosure. Specifically, participants in this study reported several reasons for disclosing that are related to medical decision making (e.g., providing information to family members, helping family members make medical decisions, and encouraging them to get tested). Interestingly, participants also noted that they felt “obligated” to share their genetic test results. This may again reflect the sense of “responsibility” that other authors have observed in this context (Montgomery et al., 2013). However, some of the reasons for disclosure suggest some knowledge gaps regarding hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and genetic testing. For example, >50% of BRCA1/2 negative and VUS participants stated that they disclosed their genetic test results because they wanted to encourage family to get tested. However, first-degree relatives of these individuals would not be recommended to have genetic testing (unless there is a known BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant in the family, or a history of cancers on the other side of their family). Given that all participants in this sample received standardized genetic counseling in the course of study participation, this highlights an important point of potential patient-provider miscommunication. This may indicate that further clarification regarding the appropriateness and applicability of cascade testing is necessary, and communication regarding potential cascade testing within the family should be reassessed by genetic providers during follow-up.

Interestingly, the least common reasons for disclosing results among participants all had to do with family members being active in the disclosure of test results (“I made an agreement to tell them before receiving my results”; “I was asked about the result from a family member”; “I was encouraged by other family members to share the information”) or active in medical decision making (“I needed advice from my family members in making medical decisions”). This may indicate that women in this study were not speaking with their family members about their testing opportunity prior to undergoing genetic testing, and that women were typically making medical decisions on their own. However, further research is needed to support these exploratory findings.

Guidelines addressing the communication of genetic information within families typically state that (1) the patient receiving genetic testing has the obligation to communicate genetic information to family members, and (2) genetics professionals should support and encourage these individuals to share information with family members (Forrest, Delatycki, Skene, & Aitken, 2007). It is encouraging that BRCA1/2 positive participants were significantly more likely to report disclosing their test results, at least in part, because a health professional encouraged them (81%). However, this study further identifies a crucial area for genetic counselors and other providers (Peipins et al., 2018) to take a more active and supportive role in the communication of genetic test results, which could have important implications for addressing health disparities in breast cancer.

While breast cancer mortality rates have declined overall since the late 1980s, Black women have a 42% higher mortality rate than White women (R. A. Smith et al., 2018). Compared to White women, Black women have a higher incidence of early onset breast cancers (diagnosed before age 50) and triple negative breast cancers (B. Daly & Olopade, 2015), which tend to be more severe and harder to treat. Additionally, breast cancer incidence increased slightly (0.7%/year) between 2000 and 2009 for Black women, while there was a decrease among White women (1.0%/year) (O’Keefe, Meltzer, & Bethea, 2015). Documented structural and systemic factors perpetuate these health disparities (O’Keefe et al., 2015), but one area that could impact early disease detection and risk management is communication of genetic test results (Becker et al., 2011). Successful interventions exist which aim to improve family history collection, disclosure of hereditary cancer risk information, and frequency of communication (Bodurtha et al., 2014), or to improve a patient’s ability to communicate genetic information with family members (Gaff & Hodgson, 2014). Adapting these successful interventions for specific family members to whom Black women are less likely to disclose could improve cancer diagnosis and outcomes in this population.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the statewide recruitment of individuals across a variety of institutions. Thus, these results are likely to be generalizable to community-based cancer survivors in Florida, rather than only those who choose to seek care at large, academic medical centers. In addition, the study sample had a relatively high retention rate, with 69% of baseline participants completing the 12 month follow-up assessment. Finally, genetic counseling and genetic testing were provided as part of the study, thereby ensuring women received similar information regarding their personal risk, and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Thus, we have greater confidence the observed patterns of disclosure were not related to differences in information provided during the process of genetic counseling and genetic testing, as might be the case in a naturalistic study of changes after genetic counseling and genetic testing provided outside of the research context.

Nonetheless, the results of the present study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, a total of ten logistic regressions were conducted, with a significance level of α = 0.05 (two-tailed) that was unadjusted for multiple comparisons. Thus, some of the results presented may be due to Type 1 error. These results must be confirmed by future studies with larger samples. In particular, larger samples of BRCA1/2 positive women may be particularly informative, as the number of participants in the present study who were BRCA1/2 positive was relatively small. Second, of the 882 women with whom we were successfully able to establish contact, only 480 (54%) consented to participate in the present study. Furthermore, drop-out rates at the 12 month follow-up time point ranged from 18–34% between groups. The results may thus be subject to selection bias. Third, disclosure of previous genetic test results was collected via self-report and may be subject to demand characteristics and social desirability. Fourth, this study did not collect information regarding half-siblings, relatives’ vital status, and – notably – age of family members to whom participants chose not to disclose. It is possible that disclosure rates to parents may be an underestimate because no data on the parent’s vital status was collected. As genetic testing is not recommended for persons under the age of 18, participants in this study may have chosen to withhold genetic information from some younger relatives. Fifth, this study did not collect information regarding family members’ prior genetic testing and/or BRCA1/2 status, nor did it ask whether family members were informed of their result by other people in the family. While the participants in this study were considered the “best testable” in their family and most were the first to undergo testing, it is possible that low rates of genetic test result disclosure to family members may be because known pathogenic variants already exist in the families of participating women, or other people disclosed the result to family members. Finally, the follow-up time point selected (12 months) may have limited our understanding of family disclosure. Other research has found that disclosure can happen in stages, and information sharing may still occur after one year (Wilson et al., 2004).

Conclusions

This study attempts to address key gaps in knowledge regarding Black women and the disclosure of genetic information to family members. In attempting to understand genetic test result disclosure patterns of Black women with their family members, we have identified family members who may be at risk of not receiving important genetic test result information. Specifically, young Black women disclose positive results to their daughters at lower rates than negative or VUS results in the first 12 months after testing. This effect may be explained by age; regardless of test result, younger women were less likely to disclose this information to their daughters. Nonetheless, the lack of disclosure of genetic test results to first-degree relatives may have direct health implications to these family members, and renews the debate over returning results to relatives directly (d’ Audiffret Van Haecke & de Montgolfier, 2016). In the meantime, this research provides guidance for practitioners to tailor discussions of disclosure of test results for this specific population, highlighting the importance of communicating positive results to certain family members. This research also encourages future qualitative study to understand the pathways for disclosure and non-disclosure for certain family members and types of genetic test results. Therefore, our findings suggest that genetic testing disclosure to family members can benefit from both patient as well as provider-targeted interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society: RSG-11-268-01-CPPB (PI: Vadaparampil), the Florida Biomedical Research Program: IBG10-34199 (PI: Pal) and the National Cancer Institute: P30CA076292 (PI: Sellers) and R25 CA090314 (PI: Brandon).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Human Studies and Informed Consent

All procedures were approved by the University of South Florida (104559) and the Florida Department of Health (DOH H11168) Institutional Review Boards. This study confirms to the standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and U.S. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. All persons gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

References

- Adams I, Christopher J, Williams KP, & Sheppard VB (2015). What black women know and want to know about counseling and testing for BRCA1/2. Journal of Cancer Education, 30(2), 344–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsevick AM, Montgomery SV, Ruth K, Ross EA, Egleston BL, Bingler R, … Daly MB (2008). Intention to communicate BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic test results to the family. J Fam Psychol, 22(2), 303–312. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker F, van El CG, Ibarreta D, Zika E, Hogarth S, Borry P, … Cornel MC (2011). Genetic testing and common disorders in a public health framework: how to assess relevance and possibilities. Background Document to the ESHG recommendations on genetic testing and common disorders. European journal of human genetics : EJHG, 19 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S6–S44. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodurtha JN, McClish D, Gyure M, Corona R, Krist AH, Rodríguez VM, … Quillin JM (2014). The KinFact intervention–A randomized controlled trial to increase family communication about cancer history. Journal of Women’s Health, 23(10), 806–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner D, Cragun D, Reynolds M, Vadaparampil ST, & Pal T (2016). Recruitment of a Population-Based Sample of Young Black Women with Breast Cancer through a State Cancer Registry. Breast J, 22(2), 166–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury AR, Dignam JJ, Ibe CN, Auh SL, Hlubocky FJ, Cummings SA, … Daugherty CK (2007). How Often Do BRCA Mutation Carriers Tell Their Young Children of the Family’s Risk for Cancer? A Study of Parental Disclosure of BRCA Mutations to Minors and Young Adults. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(24), 3705–3711. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.09.1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller L, Egleston BL, Olopade OI, Daly MB, Moore CW, … Feigon M (2012). When parents disclose BRCA1/2 test results: their communication and perceptions of offspring response. Cancer, 118(13), 3417–3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite D, Emery J, Walter F, Prevost AT, & Sutton S (2004). Psychological impact of genetic counseling for familial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst, 96(2), 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung EL, Olson AD, Tina MY, Han PZ, & Beattie MS (2010). Communication of BRCA results and family testing in 1,103 high-risk women. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 1055–9965. EPI-1010–0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers CP, Childers KK, Maggard-Gibbons M, & Macinko J (2017). National Estimates of Genetic Testing in Women With a History of Breast or Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 35(34), 3800–3806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.6314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra I, & Kelly KM (2017). Cancer Risk Information Sharing: The Experience of Individuals Receiving Genetic Counseling for BRCA1/2 Mutations. Journal of health communication, 22(2), 143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragun D, Weidner A, Kechik J, & Pal T (2019). Genetic Testing Across Young Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Breast Cancer Survivors: Facilitators, Barriers, and Awareness of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers, 23(2), 75–83. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2018.0253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’ Audiffret Van Haecke D, & de Montgolfier S (2016). Genetic Test Results and Disclosure to Family Members: Qualitative Interviews of Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions of Ethical and Professional Issues in France. Journal of genetic counseling, 25(3), 483–494. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9896-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agincourt-Canning L (2001). Experiences of genetic risk: disclosure and the gendering of responsibility. Bioethics, 15(3), 231–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly B, & Olopade OI (2015). A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin, 65(3), 221–238. doi: 10.3322/caac.21271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly MB, Montgomery S, Bingler R, & Ruth K (2016). Communicating genetic test results within the family: Is it lost in translation? A survey of relatives in the randomized six-step study. Familial cancer, 15(4), 697–706. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9889-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancyger C, Wiseman M, Jacobs C, Smith JA, Wallace M, & Michie S (2011). Communicating BRCA1/2 genetic test results within the family: A qualitative analysis. Psychology & Health, 26(8), 1018–1035. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.525640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drohan B, Roche CA, Cusack JC, & Hughes KS (2012). Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer and Other Hereditary Syndromes: Using Technology to Identify Carriers. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 19(6), 1732–1737. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2257-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehniger J, Lin F, Beattie MS, Joseph G, & Kaplan C (2013). Family communication of BRCA1/2 results and family uptake of BRCA1/2 testing in a diverse population of BRCA1/2 carriers. Journal of genetic counseling, 22(5), 603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay E, Stopfer JE, Burlingame E, Evans KG, Nathanson KL, Weber BL, … Domchek SM (2008). Factors determining dissemination of results and uptake of genetic testing in families with known BRCA1/2 mutations. Genetic testing, 12(1), 81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LE, Delatycki MB, Skene L, & Aitken M (2007). Communicating genetic information in families–a review of guidelines and position papers. European Journal of Human Genetics, 15(6), 612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaff C, Clarke AJ, Atkinson P, Sivell S, Elwyn G, Iredale R, … Edwards A (2007). Process and outcome in communication of genetic information within families: a systematic review. European Journal of Human Genetics, 15(10), 999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaff C, & Hodgson J (2014). A genetic counseling intervention to facilitate family communication about inherited conditions. Journal of genetic counseling, 23(5), 814–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves KD, Christopher J, Harrison TM, Peshkin BN, Isaacs C, & Sheppard VB (2011). Providers’ perceptions and practices regarding BRCA1/2 genetic counseling and testing in African American women. Journal of genetic counseling, 20(6), 674–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves KD, Sinicrope PS, Esplen MJ, Peterson SK, Patten CA, Lowery J, … Lindor NM (2014). Communication of Genetic Test Results to Family and Health Care Providers Following Disclosure of Research Results. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 16(4), 294–301. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MJ, & Olopade OI (2006). Disparities in genetic testing: thinking outside the BRCA box. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(14), 2197–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MJ, Reid JE, Burbidge LA, Pruss D, Deffenbaugh AM, Frye C, … Noll WW (2009). BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in women of different ethnicities undergoing testing for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. Cancer, 115(10), 2222–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel H, Bennett RL, Buchanan A, Pearlman R, & Wiesner GL (2014). A practice guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: referral indications for cancer predisposition assessment. Genetics in Medicine, 17, 70. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T, McCarthy AM, Kim Y, & Armstrong K (2017). Predictors of BRCA1/2 genetic testing among Black women with breast cancer: a population-based study. Cancer medicine, 6(7), 1787–1798. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian-Reynier C, Eisinger F, Chabal F, Lasset C, Noguès C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, … Sobol H (2000). Disclosure to the family of breast/ovarian cancer genetic test results: Patient’s willingness and associated factors. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 94(1), 13–18. doi:doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegelaers D, Merckx W, Odeurs P, van den Ende J, & Blaumeiser B (2014). Disclosure pattern and follow-up after the molecular diagnosis of BRCA/CHEK2 mutations. Journal of genetic counseling, 23(2), 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian AW, Griffith KA, Hamilton AS, Ward KC, Morrow M, Katz SJ, & Jagsi R (2017). Genetic Testing and Counseling Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Breast CancerGenetic Testing and Counseling Among Patients With New-Onset Breast CancerLetters. Jama, 317(5), 531–534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafreniere D, Bouchard K, Godard B, Simard J, & Dorval M (2013). Family communication following BRCA1/2 genetic testing: a close look at the process. J Genet Couns, 22(3), 323–335. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9559-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster JM, Powell CB, Chen L. m., & Richardson DL (2015). Society of Gynecologic Oncology statement on risk assessment for inherited gynecologic cancer predispositions. Gynecologic oncology, 136(1), 3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DE, Byfield SD, Comstock CB, Garber JE, Syngal S, Crown WH, & Shields AE (2011). Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genetics in Medicine, 13(4), 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodder L, Frets PG, Trijsburg RW, Tibben A, Meijers-Heijboer EJ, Duivenvoorden HJ, … Cornelisse CJ (2001). Men at risk of being a mutation carrier for hereditary breast/ovarian cancer: an exploration of attitudes and psychological functioning during genetic testing. European Journal of Human Genetics, 9(7), 492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch HT, Lemon SJ, Durham C, Tinley ST, Connolly C, Lynch JF, … Narod S (1997). A descriptive study of BRCA1 testing and reactions to disclosure of test results. Cancer, 79(11), 2219–2228. doi:doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch HT, Snyder C, Lynch JF, Karatoprakli P, Trowonou A, Metcalfe K, … Gong G (2006). Patient responses to the disclosure of BRCA mutation tests in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer families. Cancer genetics and cytogenetics, 165(2), 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madlensky L, Trepanier AM, Cragun D, Lerner B, Shannon KM, & Zierhut H (2017). A Rapid Systematic Review of Outcomes Studies in Genetic Counseling. J Genet Couns. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0067-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai PL, Vadaparampil ST, Breen N, McNeel TS, Wideroff L, & Graubard BI (2014). Awareness of Cancer Susceptibility Genetic Testing: The 2000, 2005, and 2010 National Health Interview Surveys. American journal of preventive medicine, 46(5), 440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister MF, Evans D, Ormiston W, & Daly P (1998). Men in breast cancer families: a preliminary qualitative study of awareness and experience. J Med Genet, 35(9), 739–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy AM, Bristol M, Domchek SM, Groeneveld PW, Kim Y, Motanya UN, … Armstrong K (2016). Health Care Segregation, Physician Recommendation, and Racial Disparities in BRCA1/2 Testing Among Women With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 34(22), 2610–2618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern B, Everett J, Yager GG, Baumiller RC, Hafertepen A, & Saal HM (2004). Family communication about positive BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic test results. Genetics in Medicine, 6(6), 503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, … Ding W (1994). A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science, 266(5182), 66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SV, Barsevick AM, Egleston BL, Bingler R, Ruth K, Miller SM, … Daly MB (2013). Preparing individuals to communicate genetic test results to their relatives: report of a randomized control trial. Fam Cancer, 12(3), 537–546. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9609-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe EB, Meltzer JP, & Bethea TN (2015). Health Disparities and Cancer: Racial Disparities in Cancer Mortality in the United States, 2000–2010. Frontiers in public health, 3(51). doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal T, Bonner D, Cragun D, Monteiro AN, Phelan C, Servais L, … Vadaparampil ST (2015). A high frequency of BRCA mutations in young black women with breast cancer residing in Florida. Cancer, 121(23), 4173–4180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patenaude AF, Dorval M, DiGianni LS, Schneider KA, Chittenden A, & Garber JE (2006). Sharing BRCA1/2 test results with first-degree relatives: factors predicting who women tell. J Clin Oncol, 24(4), 700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patenaude AF, Tung N, Ryan PD, Ellisen LW, Hewitt L, Schneider KA, … Garber JE (2013). Young adult daughters of BRCA1/2 positive mothers: What do they know about hereditary cancer and how much do they worry? Psycho-Oncology, 22(9), 2024–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peipins LA, Rodriguez JL, Hawkins NA, Soman A, White MC, Hodgson ME, … Sandler DP (2018). Communicating with Daughters About Familial Risk of Breast Cancer: Individual, Family, and Provider Influences on Women’s Knowledge of Cancer Risk. Journal of Women’s Health, 27(5), 630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley BD, Culver JO, Skrzynia C, Senter LA, Peters JA, Costalas JW, … Trepanier AM (2012). Essential Elements of Genetic Cancer Risk Assessment, Counseling, and Testing: Updated Recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Journal of genetic counseling, 21(2), 151–161. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson M, & Offit K (2007). Management of an inherited predisposition to breast cancer. New England journal of medicine, 357(2), 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson ME, Bradbury AR, Arun B, Domchek SM, Ford JM, Hampel HL, … Lindor NM (2015). American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement Update: Genetic and Genomic Testing for Cancer Susceptibility. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(31), 3660–3667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland E, & Metcalfe A (2013). Communicating inherited genetic risk between parent and child: a meta-thematic synthesis. International journal of nursing studies, 50(6), 870–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland E, Plumridge G, Considine A-M, & Metcalfe A (2016). Preparing young people for future decision-making about cancer risk in families affected or at risk from hereditary breast cancer: A qualitative interview study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr CL, Christie J, & Vadaparampil ST (2016). Breast cancer survivors’ knowledge of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer following genetic counseling: an exploration of general and survivor-specific knowledge items. Public health genomics, 19(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard VB, Graves KD, Christopher J, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Talley C, & Williams KP (2014). African American women’s limited knowledge and experiences with genetic counseling for hereditary breast cancer. Journal of genetic counseling, 23(3), 311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, West JA, Croyle RT, & Botkin JR (1999). Familial context of genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: moderating effect of siblings’ test results on psychological distress one to two weeks after BRCA1 mutation testing. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 8(4), 385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Fedewa SA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, … Wender RC (2018). Cancer screening in the United States, 2018: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 68(4), 297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai YC, Domchek S, Parmigiani G, & Chen S (2007). Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst, 99(23), 1811–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Mays D, DeMarco TA, Peshkin BN, Valdimarsdottir HB, Schneider KA, … Patenaude AF (2013). Decisional outcomes of maternal disclosure of BRCA1/2 genetic test results to children. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 22(7), 1260–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, Seo J, Griffith J, Baxter M, James A, & Kaphingst KA (2015). The Context of Collecting Family Health History: Examining Definitions of Family and Family Communication about Health among African American Women. Journal of health communication, 20(4), 416–423. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.977466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner Costalas J, Itzen M, Malick J, Babb JS, Bove B, Godwin AK, & Daly MB (2003). Communication of BRCA1 and BRCA2 results to at-risk relatives: a cancer risk assessment program’s experience. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 119c(1), 11–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.10003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells AA, Gulbas L, Sanders-Thompson V, Shon E-J, & Kreuter MW (2014). African-American Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in a Breast Cancer Support Group: Translating Research into Practice. Journal of Cancer Education, 29(4), 619–625. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0592-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BJ, Forrest K, van Teijlingen ER, McKee L, Haites N, Matthews E, & Simpson SA (2004). Family communication about genetic risk: the little that is known. Public health genomics, 7(1), 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, … Micklem G (1995). Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature, 378(6559), 789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]