Abstract

We report on innovating protocols at an Academic Pediatric practice during the COVID-19 (2019 novel coronavirus) crisis. Facing the challenges of limited personal protective equipment and testing capacity, we rapidly and efficiently changed processes to optimize infection control, providing safe and effective care for our vulnerable population.

Key Words: Outpatient practice, Pediatrics, COVID-19, Novel coronavirus

During the COVID-19 (2019 novel coronavirus) crisis, pediatric practices are being challenged to evolve rapidly and adapt operations to a constantly changing situation. Our objective is to report on how we operationalized processes in an academic practice to optimize infection control, safety, and patient care, with a focus on vulnerable populations.

Setting

A pediatric practice within an academic medical center with 18,184 annual visits. Our office is staffed with 10 attending physicians, 30 residents, 4 nurse practitioners, 2 nurses, 2 social workers, and 1 lactation consultant. We serve an urban, minority, and low income community (Medicaid 85%).

Key drivers for process change

-

1.

Maintain a safe environment for staff and patients through stringent infection control procedures.

-

2.

Provide care to sick and potentially COVID-19 infected pediatric patients in a setting with limited testing capacity and personal protective equipment (PPE).

-

3.

Protect vulnerable populations through continued essential care including age appropriate immunizations.

We aligned our guidance with the local department of health, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 , 2

The process of change

Our leadership team consisted of the Medical Director, Department Chair, a Pediatric Infectious Disease attending, and the Practice Manager. Strategizing teamwork through engaging every staff member served to maintain high levels of motivation and morale. Leaders held daily huddles and delegated to task specific committees on issues including newborn care and telemedicine, allowing for innovation at a rapid rate. Leadership fostered flexibility, openness to change, creativity, and transparency.

Adjusting operations

Infection control procedures Refer to Table 1

Table 1.

Infection control procedures

| Process | Change |

|---|---|

| Front desk screening |

|

| Waiting room |

|

| Source control |

|

| Staff PPE |

|

| Staff education |

|

| Patient and staff cohorting |

|

| Disinfection | Patient rooms were disinfected after each encounter including highly touched surfaces such as bed, equipment, doorknobs, and keyboards. |

Phone triage

When downscaling in person visits, effective and empathetic phone triage is key. Clinicians asked key questions to identify signs of acute illness. We alleviated parental anxiety and explained the criteria for COVID-19 testing to families in a clear manner. Arranging telemedicine visits was instrumental in reducing exposures.

Telemedicine

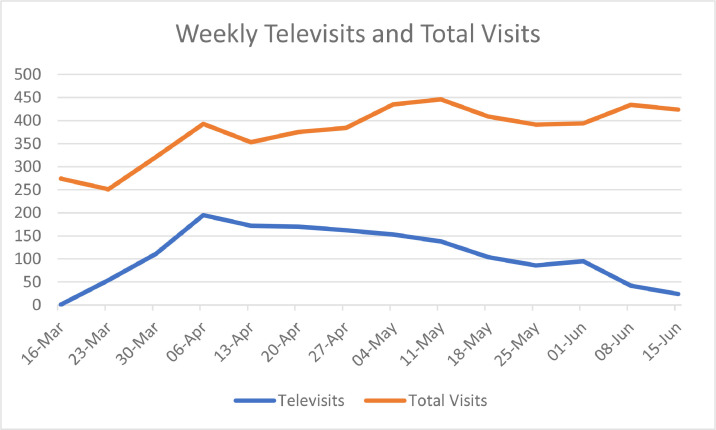

We explored and trialed several video platforms and secured laptops and tablets. Telemedicine billing training was provided to ensure adequate documentation. We created a televisit “script” with guidance for history and physicals and embedded templates within the electronic medical record.2 , 4 After a 2 week planning period, we rapidly implemented televisit access (refer to Fig 1 ).

Fig 1.

Number of weekly televisits and total visits

Changes to well visits

Our practice scaled back well visits to children ≤15 months requiring vaccines. Hybrid visits, which involved obtaining histories and routine screenings (ie, autism screening) by phone prior to the visit, served to expedite the physical exam and vaccines on arrival. Oral fluoride varnish was deferred given its transmission risk.5 Blood draws for routine complete blood count and lead were deferred.

Changes to sick visits

Sick visits were initially limited to infants, and those with respiratory distress or wheezing, otalgia, fever ≥39°C for >48 hours, or sore throat without viral symptoms. With the COVID-19 surge and rampant community spread, sick visits were further limited to those at risk for respiratory distress or dehydration, fever with no source, and/or underlying conditions. All aerosolized procedures, including suctioning and nebulizations, were halted, and patients with asthma were instructed to bring in their inhalers. Video visits were particularly useful to visualize rashes and assess patient breathing, throat exams, and hydration status. We identified multiple severely ill patients requiring hospital admission through televisits.

Normally, we practice robust antibiotic stewardship, adhering to American Academy of Pediatrics/Infectious Diseases Society guidelines for Group A streptococcal pharyngitis, otitis media and sinusitis. During the COVID-19 surge, we suspended visits for otitis media and pharyngitis and instead relied on strong histories and video physicals to determine whether antibiotics were necessary. When appropriate, we adhered to 48-hour observation for otitis media prior to antibiotic prescribing.

Due to limited PPE and testing kits, COVID-19 testing was restricted to symptomatic patients with underlying high risk conditions, those living in a congregate settings, and infants <12 months given their potential for more severe illness.6 We created a patient tracking system to follow up on patients who received a COVID-19 test, and/or were presumed or confirmed COVID-19 positive, to ensure decompensation would not be missed. Through frequent follow up televisits, we instructed patients to self-isolate and monitor for shortness of breath, increased work of breathing, and chest pain.

Patient transfers

For COVID-19 suspected patients in need of transfer to the emergency department, both emergency room and Infection Control teams were alerted prior to patient arrival. In addition, we developed a plan with the adult emergency team in our facility to offload stable non-COVID pediatric patients to our clinic for further evaluation and treatment, freeing up emergency room capacity.

Adolescent care

Sexually transmitted screening and treatment and contraception were deemed essential care.

Vulnerable populations

Newborns were viewed as vulnerable given the risk of feeding issues, abnormal weight loss, and kernicterus. Televisits and in person visits with an alternative caretaker were provided for newborns born to a confirmed COVID-19 positive mother. Virtual lactation consults were provided. Infant scale home delivery was arranged through insurance companies.

Children with special needs/comorbid conditions including Asthma received ongoing monitoring through televisits. Medications and equipment were sent to a home delivery pharmacy. Patients with a history of child protective services involvement were called by our social worker for check ins.

Education

Residents were divided into 2 teams, with one team working remotely to obtain and document histories, while the other completed both televisits and in person encounters in the clinic with attending oversight.

Advocacy

In times of school closures and economic hardships, there is concern for increased rates of child abuse.7 We discussed parenting tips verbally and through written patient portal messages. We screened for food insecurity and provided appropriate resources. COVID-19 is affecting minority populations, especially African Americans and Latinx communities in Philadelphia and around the country disproportionately, thus we continued to message safety to the community.8

Discussion

As a result of our protocol, we had zero health care worker related infections and expanded access to care for our patients. We successfully increased our televisits from 0 % initially to 48 % of total visits during our local COVID-19 peak. We are now implementing a staggered and careful expansion of well visits to all ages. We will continue to cohort patients by illness status, with separation in space and time when possible. We will also separate patients by age, based on data that COVID-19 infection tends to be less common in those aged <10 years.6 , 9 We will resume routine complete blood count and lead blood testing. Resumption of visits requiring point of care testing and/or an antibiotic prescription is a priority. Maintaining adequate PPE and disinfectant supply along with universal masking and social distancing is key to safe operational expansion. Further, we anticipate addressing parental fear as a barrier to in person visits. To contain COVID-19, public health experts advocate a test, trace, isolate strategy.10 In anticipation of school reopening, we are working to expand testing capacity for pediatric patients in the ambulatory setting. A revision of our protocol is contingent on studying outcome measures such immunization delay, process measures such as televisit uptake, and balancing measures such as mismanagement of chronic conditions or missed diagnoses.

Conclusions

Outpatient practices are encouraged to innovate protocols that can be adapted to their specific patient population, community, and practice structure. These protocols should evolve to fill any vacuums in practice policies, to optimize operations making them both safe and efficient, and to incorporate emerging guidance from facility infection control, public health experts and renowned medical organizations.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the entire staff at the Pediatric and Adolescent Ambulatory Care Center at Einstein Philadelphia for the strong teamwork, positive attitude, and deep dedication to patient care.

Footnotes

Financial Support: None reported.

Conflict of Interest: None to report.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics . April 15, 2020. Guidance on providing pediatric ambulatory services via telehealth during COVID 19.https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections2/guidance-on-providing-pediatric-ambulatory-services-via-telehealth-during-covid-19/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . March 30, 2020. Phone advice line tool for possible COVID-19 patients.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/phone-guide/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fphone-guide%2Findex.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 3.April 3, 2020. Recommendation regarding use of cloth face coverings, especially in areas of significant community-based transmission Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover.html Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenhalgh T, Koh Gerald CH, Josip C. Covid-19: a remote assessment in primary care. BMJ. 2020;368:m1182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Paediatrics and British Health . April 20, 2020. COVID-19 - guidance for paediatric services.https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-guidance-paediatric-services Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronavirus disease 2019 in children — United States, February 12–April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:422–426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146:e20200982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323:1891–1892. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason A, Jonsson H, et al. 2020. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic Population. N Engl J Med. ;382:2302-2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walensky RP, Del Rio C. From mitigation to containment of the COVID-19 pandemic: putting SARS-CoV-2 genie back in the bottle. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6572. ;323:1889-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]