Abstract

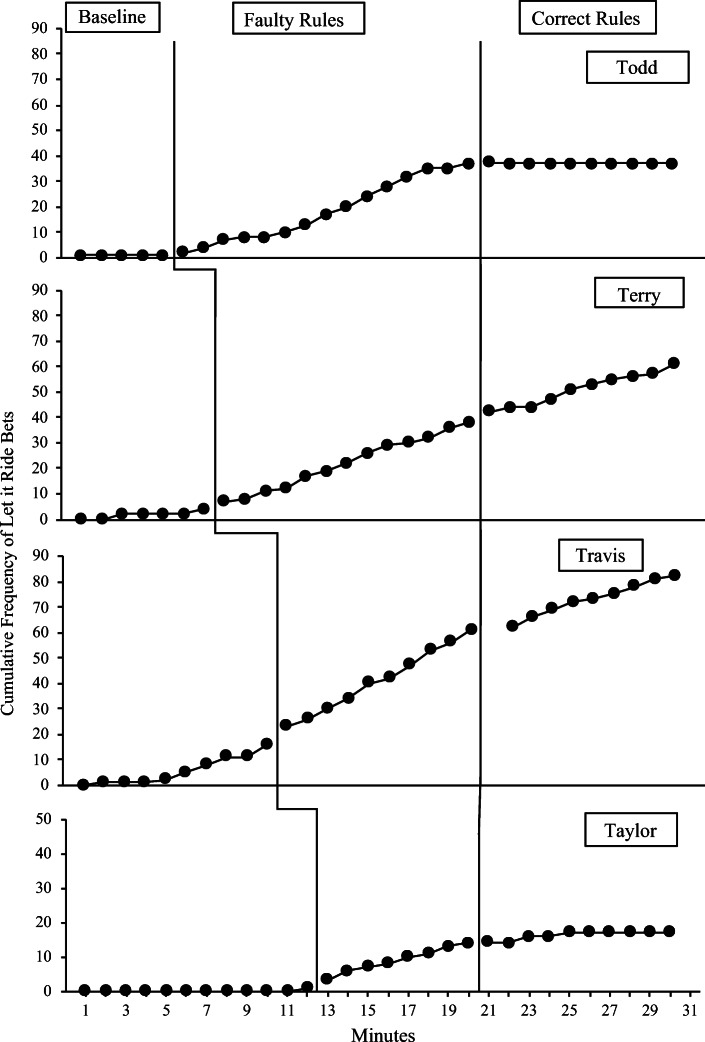

The present study replicated and extended previous research by exploring the extent to which rules altered participants’ engagement in risky betting in an electronic blackjack game. A multiple-baseline across-participants design with predetermined phase changes was used to assess 4 recreational gamblers’ betting patterns in blackjack across 3 phases. During baseline, participants played blackjack with no exposure to rules. In the faulty rules phase, researchers gave participants a rule that suggested larger payouts would occur if gamblers played let-it-ride bets. Let-it-ride bets were placed after a winning hand and required participants to wager their entire winnings on the next hand. During the correct rules phase, researchers gave participants a rule that suggested that the let-it-ride bets did not result in larger payouts. Data on let-it-ride bets across each minute of play were collected. The results of the study demonstrated that the frequency of risky bets increased when participants were exposed to the incorrect rule. Following participants’ exposure to correct rules, risky bets decreased, but most participants did not return to baseline rates.

Keywords: Behavior analysis, Gambling, Multiple baseline, Risk, Rule following

Gambling is an activity that occurs around the world wherein patrons wager items of value on a variable or change outcome (Dixon, Whiting, Gunnarsson, Daar, & Rowsey, 2015). In the United States alone, 78% of the adult population report gambling at least once in their lifetimes (Kessler et al., 2008), resulting in major consumer spending that continues to increase (to over $38.96 billion in 2015; American Gaming Association, 2016). Gambling disorder arises from a pattern of repeated gambling, attempts to win back losses with continued wagers, and persistent thoughts about future wagers (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and it impacts 2.6% of the U.S. population (North American Foundation for Gambling Addiction Help, 2016; Welte, Barnes, Tidwell, Hoffman, & Wieczorek, 2015).

Verbal behavior is one fundamental component of gambling (Weatherly & Dixon, 2007). Rules and rule-governed behavior allow the gambler to avoid aversive consequences and to delay encountering aversive stimulation. For instance, a gambler operating under the rule after a long cold streak comes a jackpot may continue to gamble to obtain a potentially forthcoming jackpot (e.g., Dixon, Hayes, & Aban, 2000). Recent research on the verbal influences of gambling has shown how rules that are derived from conditional discrimination tasks can influence choices and response allocation in various gambling contexts (e.g., Dixon, Wilson, & Whiting, 2012; Hoon, Dymond, Jackson, & Dixon, 2008; Zlomke & Dixon, 2006).

One particular phenomenon is the illusion of control, or the belief that engaging in a behavior increases access to reinforcement even when the behavior has no direct effect on the probability of a success (e.g., Dixon, 2000; Dixon, Jackson, Delaney, Holton, & Crothers, 2007; Dixon, MacLin, & Hayes, 1999). The illusion of control may manifest itself through rules in a gambling context. For example, Dixon (2000) conducted an experiment wherein participants could place their own bets (with control) or have a dealer place a bet for them (without control). During baseline, participants were not exposed to rules and could wager anywhere on the table. Following the baseline phase, gamblers were given a set of rules that suggested the dealer would purposely place bets so that the gambler would lose. Along with the previous rule, another rule stated that larger bets had higher odds of winning. In the final phase, gamblers were given a new set of rules that suggested that betting greater amounts of money did not alter the odds of winning and that the dealer could not purposely pick losing numbers. The results demonstrated that gamblers wagered more when they controlled chip placement during the phase with incorrect rules. Once the accurate rules were introduced, participants decreased the rate of betting with control and the magnitude of their wagers, but not to the baseline level. These findings suggest that the impact of the initial rule was weakened, rather than completely eliminated (Dixon, 2000). Therefore, eliminating the control of the rule, faulty or not, is more difficult than presenting contradictory information.

Wong and Austin (2008) examined the impact of the illusion of control on both experienced and inexperienced gamblers. Like past research, the experiment tested the illusion of control with roulette play. Participants were told that each trial would begin with a default wager on 8:1 odds placed by the experimenter. In order for participants to gain control, they would have to spend $0.25, which would not be included in the wager; however, to control placement and have less risk, participants would have to spend an additional $0.50. The results of the study showed that experienced gamblers placed more bets with control, whereas inexperienced gamblers refrained from paying for control of bet placement. These findings show that inexperienced gamblers may be less likely to be susceptible to the illusion of control, especially when there is no perceived benefit for betting with control.

The illusion of control has also been shown to influence engagement in risky betting with experienced gamblers (however, see Wong & Austin, 2008, for research supporting gamblers not engaging in illusions of control). Risky bets can be conceptualized as placing a bet of a greater magnitude than previous bets or placing bets with smaller odds of winning (Ladouceur, Mayrand, & Tourigny, 1987). Gamblers engaging in verbal rules consistent with the illusion of control may engage in risky bets at higher rates even though doing so would result in greater losses over time (e.g., Dixon, 2000). One structural design of electronic gaming devices is progressive betting features, including “let-it-ride” bets, or when a gambler bets his or her winnings from a previous wager. For instance, if the gambler bet $20.00 on a single hand and won (i.e., total pot = $40.00), a let-it-ride bet allows him or her to wager $40.00 on the next hand. If the gambler loses the next hand (the second hand), no profits are gained, and the gambler loses the winnings from the first hand (e.g., $40.00), functionally losing both hands. However, minimal research has examined the impact of rules and the engagement in risky betting, particularly on games beyond roulette. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to replicate and extend the findings of Dixon (2000) to a novel gambling setting (i.e., electronic blackjack).

Method

Participants, Setting, and Materials

Four gamblers with prior exposure to gambling were recruited through flyers and word of mouth to participate. All participants completed the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987), which measures the proclivity toward gambling problems. Scores of 3 or greater signify a risk of gambling disorder. Demographics for each participant are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Sample

| Participant | Age | Race | Gender | SOGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Todd | 61 | Caucasian | Male | 1 |

| Terry | 19 | African American | Female | 2 |

| Travis | 21 | Caucasian | Male | 1 |

| Taylor | 33 | Caucasian | Female | 0 |

Note. SOGS = South Oaks Gambling Screen

The setting of the experiment was a 7 m × 2.5 m casino-replica lab at a university in the Midwest. The present experiment required the use of a blackjack game on an electronic gaming machine (EGM; see Fig. 1). The single-deck blackjack game operated on a random ratio schedule of reinforcement. The game allowed minimum bets of 1 credit ($0.10) and a base maximum bet of 10 credits ($1.00). However, the maximum bet could increase depending on let-it-ride betting (e.g., a base bet of 10 credits and a subsequent let-it-ride bet would place a 20-credit bet). To place a bet, participants had the option to use the touch screen via the deal button or physical buttons on the machine. Let-it-ride bets were a feature presented on the touch screen, just to the left of the deal button, which were presented following wins. Data were taken with pencil and paper, and researchers used two timers to signal the termination of each 1-min interval and the termination of each experimental condition.

Fig. 1.

Image of the electronic blackjack game participants played

To increase participation, researchers staked participants with credits equivalent to $100.00 (1,000 credits) and explained the incentive system, wherein 50 credits could be exchanged for a raffle ticket for a $50.00 gift card at the end of the study. Participants received a range of one to two tickets after play. All participants received the same probability of winning the ticket regardless of their performance during the activity.

Dependent Measures and Interobserver Agreement

Dependent measures included winning hands (opportunities to let it ride), risky bets conceptualized as those of a greater magnitude than previous bets (the number of let-it-ride bets engaged in), and the total number of bets placed that occurred throughout each condition. Let-it-ride bets were bets that wagered the winnings from a previous hand. A let-it-ride bet could be placed by pressing the let-it-ride option on the touch screen of the blackjack game following winning hands (see Fig. 1).

Total-count interobserver agreement (IOA) was collected during the entirety of the session for three of the four participants’ sessions. IOA was calculated by dividing the total number of let-it-ride agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. IOA for Terry was 95%, for Travis was 95%, and for Taylor was 89%, with an average agreement of 93%.

Experimental Design and Analyses

A multiple-baseline across-participants design with predetermined phase changes was used (similar to the design strategy employed by Wilson & Dixon, 2014). Each participant gambled for 30 min, with the duration of time played in each phase varying across participants. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four legs in the design, and during baseline, they gambled for 5, 7, 10, or 12 min in Legs 1–4, respectively. The length of the faulty rules condition was dependent on the baseline period and lasted 15, 13, 10, and 8 min. All participants played for 10 min in the correct rules phase.

Standard mean difference (SMD) scores were calculated as a secondary analysis. The SMD calculation yields an effect size (d), which allows standardized comparison across participants (see Olive & Franco, 2008, for a description). A general rule for interpretation of the SMD scores is as follows: 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 medium, and 0.8 large. SMD scores were calculated to compare baseline to the faulty rules condition, baseline to the correct rules condition, the faulty rule and the correct rule conditions. A positive number would mean that there was an increase during the experimental condition relative to the comparison condition (baseline).

Procedure

Prior to beginning the study, participants completed consent forms, a demographic survey, and the SOGS.

Baseline

Participants were asked to sit in front of the EGM and were given credits equivalent to $100.00. The researcher read the following instructions to participants prior to starting baseline: “You will now get to play video blackjack. You may play however you wish. At some point during your playing time, we will give you a hot tip. Do you have any questions?” Once all questions had been answered, the participant was instructed to begin. The baseline phase continued until researchers instructed the participants to stop at 5, 7, 10, and 12 min depending on placement in the design.

Faulty Rules Condition

This condition examined the effect of exposure to a faulty rule. After completing baseline, researchers instructed the participants to stop play, and read the following statement out loud to the participants: “If you want to win bigger, try to let it ride. It actually gives you better odds of winning. Begin.” The researchers started the timers at the same time as the instruction to begin and allowed the participants to play in this condition for 15, 13, 10, or 8 min.

Correct rules Condition

This condition examined the effect a contradictory rule, the correct rule, would have on risky betting. After completing the faulty rules condition, researchers instructed the participants to stop gambling play, and read the following statement out loud to the participants: “It turns out letting it ride does not impact your odds of winning. It is a riskier bet, and you may lose more!” After instructing the participant to begin, the researchers then started a timer for 10 min and allowed the participant to continue gambling.

Results and Discussion

Table 2 displays the total number of let-it-ride bets and wins across conditions for all participants. Similarly, Fig. 2 displays cumulative responses in which participants engaged in a risky bet (i.e., letting it ride) on the primary y-axis across each minute of play. In baseline, participants placed let-it-ride bets at variable rates (Todd: 1, Terry: 4, Travis: 16, and Taylor: 1). Following the introduction of the faulty rules, all participants increased risky betting (Todd: 36, Terry: 34, Travis: 45, and Taylor: 14). These numbers should be put in perspective of the percentage of bets per opportunity relative to baseline to allow for a fair comparison between phases, as they were different lengths of time. Given the opportunities to place risky bets, all four participants increased their risky betting per opportunity from baseline to the faulty rules condition as well (Todd: 8% to 73%, Terry: 20% to 58%, Travis: 40% to 80%, and Taylor: 2% to 38%). During the correct rules phase, three of the four participants decreased rates of risky betting (Todd: 0, Travis: 21, and Taylor: 3), with Terry engaging in let-it-ride bets at a similar rate to the faulty rules condition (23). Todd, Travis, and Taylor all demonstrated immediate changes in rates of risky betting following the introduction of the correct rules. However, only Todd and Taylor maintained the decreased rate of risky betting during this final phase.

Table 2.

Total Number of Let-It-Rides (LIRs) per Condition and Total Number of Wins per Condition

| Baseline LIRs/Total Opportunities | Baseline Win Rate | Faulty Rules LIRs/Total Opportunities | Faulty Rules Win Rate | Correct Rules LIRs/Total Opportunities | Correct Rules Win Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Todd | 1/12 | 2.4 | 36/49 | 3.3 | 0/46 | 4.6 |

| Terry | 4/20 | 2.9 | 34/59 | 2.6 | 23/46 | 4.6 |

| Travis | 16/40 | 4 | 45/56 | 5.6 | 21/52 | 5.2 |

| Taylor | 1/51 | 4.3 | 14/37 | 4.6 | 3/49 | 4.9 |

Fig. 2.

Depiction of selecting let-it-rides during play. Note that Minute 21, Travis did not have an opportunity to place a let-it-ride bet

Table 2 displays the cumulative frequency of let-it-ride bets, the opportunities to place those bets, and the rate of wins per condition. Notably, the win rates for all participants did not change dramatically from baseline to the faulty rules condition, suggesting that let-it-ride bets were under the control of rule governance, rather than the contingencies of the environment.

SMD scores were calculated to supplement the visual analyses (see Fig. 3). All participants demonstrated large effects between baseline and the faulty rules phase (Todd: d = 4.92, Terry: d = 2.09, Travis: d = 1.63, and Taylor: d = 5.34). Relative to baseline, only Todd (d = −0.44) demonstrated a small decrease in let-it-ride bets in the correct rules condition. Terry (d = 1.81) demonstrated a similar difference in the correct rules condition to that of the faulty rules condition. Travis (d = 0.41) demonstrated a small increase in risky bets. Taylor (d = 0.75) moderately increased the number of risky bets placed in the correct rules condition relative to baseline. Relative to the faulty rules condition, the introduction of correct rules produced a large decrease in risky bets for Todd (d = −1.71), Travis (d = −1.37), and Taylor (d = −1.78). Terry (d = −0.22) demonstrated a small decrease in risky bets.

Fig. 3.

Standard mean difference scores across participants and conditions

Given the results, the present study extends research on rule-governed behavior and risky bets conceptualized as placing bets of greater magnitude than previous bets. Participants were exposed to two rules: one that incorrectly stated the contingencies (faulty rule) and one that correctly stated the contingencies (correct rule). Following exposure to the faulty rule, all participants increased the number of the let-it-ride bets they wagered. Following the introduction of the correct rule, all participants decreased the rate of risky bets relative to the faulty rules condition, but only Todd decreased back to near-baseline levels. Further, the results from the SMD analyses suggest that the contradictory rule significantly weakened the control of the faulty rule. However, relative to the baseline condition, Todd, Travis, and Taylor demonstrated an increase in risky bets during the correct rules condition. Such an effect can be explained by considering rule following as an operant behavior (Dixon, 2000).

Skinner (1974) suggested that “all behavior is determined, directly or indirectly, by consequences” (p. 127), and verbal stimuli and subsequent rule following come under similar contextual control. In the case of rule governance, the behavior impacted by the rules is indirectly impacted by the history of rule following. Moreover, the strength of the effect can be explained in part by the fact that rule-governed behavior is more rapidly acquired than contingency-shaped behavior (Skinner, 1974). In fact, this aspect of rule-governed behavior may be disadvantageous to the gambler, as gamblers develop inaccurate rules. Therefore, it may take longer for the contingencies of the environment to come into control of gambling behavior, whereas inaccurate rules make continued gambling occur during losing streaks. Further, the faulty rule described the let-it-ride button as a discriminative stimulus, which would increase the odds of winning.

The results of the present study replicate previous research, particularly the extent to which rules can influence gambling behaviors (e.g., Dixon, 2000; Wilson & Dixon, 2014; Wilson & Grant, 2015; Zlomke & Dixon, 2006). Notably, when exposed to rules regarding the increased likelihood of winning, participants reliably allocated responding to coincide with the rule. The current study further supported the strengthening and weakening of rules over time. The correct rule weakened the strength of the faulty rule, as demonstrated by the decreased responding relative to the correct rules phase by Terry, Travis, and Taylor. This is similar to the outcomes of Dixon (2000), in that participants decreased the magnitude of bets during the phase in which accurate rules were presented. However, the current study controlled for the possible effects of observational learning present in Dixon (2000), by having each participant alone in the gambling setting. In doing so, the effects found in the current study can be better attributed to the rules.

It is notable that not all past research suggests that gamblers will engage in the illusion of control. Wong and Austin (2008) found that inexperienced gamblers did not place bets with control, whereas experienced gamblers were more likely to do so. However, the present study differed from Wong and Austin (2008) in two key ways. First, the faulty rules condition presented rules that suggested that controlling bets through the let-it-ride feature would increase the odds of winning and that participants could “win bigger.” The rules from Wong and Austin (2008) did not suggest any benefit from placing bets with control, aside from placing bets with less risk. Second, the procedure from Wong and Austin (2008) required participants to pay money independent of their wagers to bet with control. This procedure made the decision to bet with control costly, as participants did not see their spending be incorporated in their wagers. However, by letting it ride, participants betting with control in the present study did not have to spend money outside of their wagers. Therefore, we believe these findings can be judged independently from the findings of Wong and Austin (2008).

The present analysis is not without limitations. One limitation is the potential confound of increased engagement in let-it-ride bets prior to ending baseline. For instance, Terry, Travis, and Taylor all placed a let-it-ride bet in the last minute of play, which could have impacted the extent to which participants would have continued to let it ride without further intervention (i.e., carryover effects). However, all participants were randomly assigned to one of the legs within the design and demonstrated increased averages of risky bets in the faulty rules phase. Further, there were fewer instances in which participants did not place any risky wagers per minute in the faulty rules phase, which was common in the baseline phases across participants. This finding suggests that the predetermination of the phase lengths may not confound the results (see also Kratochwill & Levin, 2014).

A second limitation is that the saliency of the let-it-ride bet increases as rules are presented throughout the study. In other words, let-it-ride betting could have increased simply due to the experimenter pointing out the location of the let-it-ride button on the screen. However, it should be noted that all participants did engage in let-it-ride bets during baseline, suggesting some familiarity with this betting option. Second, the let-it-ride button is displayed in red on the touch screen, whereas the deal (i.e., repeat bets) button is yellow and is only available following wins. The presentation of a novel button and novel color among the betting options may have been salient enough for gamblers to orient to the bet option, evidenced by placing a let-it-ride bet in baseline. Similarly, given that all participants were exposed to the same order of rules, it is unclear as to the extent to which similar effects would be observed if the rules were reversed or presented to participants in a different order. The possibility of sequence effects limits the findings, and future research should seek to compare groups of participants who are exposed to different sequences of rule presentation. Finally, the present study did not include individuals at risk of developing a gambling disorder. Therefore, it is difficult to generalize the current results to a clinical population of those with a gambling disorder.

Future research can mitigate these limitations by controlling for the saliency of button options during the gambling activity and should control for sequence effects of the different types of rules. Future research should also analyze whether there is a primacy effect for gamblers’ rule following. Because all gamblers in the study altered responding to place more risky bets following the initial rule, and most gamblers did not eliminate risky bets following the second rule, a primacy effect could not be analyzed presently. However, another study that controls which rule was presented first could begin to answer the question of how the ordering of rules impacts rule following. It would also be beneficial to ascertain whether other gambling patterns can be similarly impacted by rules, such as progressive betting. Progressive betting occurs when a gambler doubles a previous bet when he or she has lost the previous hand. Progressive betting purports to decrease losses over time. Finally, it would be beneficial to include a population of individuals with a gambling disorder to determine if a similar pattern of responding would occur.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This study was not funded with any external funds.

Informed Consent

Informed parental consent and participant assent were obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Gaming Association. (2016). State of the states: The AGA survey of the casino industry. Retrieved from https://www.americangaming.org/sites/default/files/2016%20State%20of%20the%20States_FINAL.pdf

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR. Manipulating the illusion of control: Variations in gambling as a function of perceived control over chance outcomes. The Psychological Record. 2000;50(4):705. doi: 10.1007/BF03395379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Hayes LJ, Aban IB. Examining the roles of rule following, reinforcement, and preexperimental histories on risk-taking behavior. The Psychological Record. 2000;50(4):687–704. doi: 10.1007/BF03395378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Jackson JW, Delaney J, Holton B, Crothers MC. Assessing and manipulating the illusion of control of video poker players. Analysis of Gambling Behavior. 2007;1(2):90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, MacLin OH, Hayes LJ. Toward molecular analysis of video poker play. Behavior Research Methods. 1999;31(1):185–187. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Whiting SW, Gunnarsson KF, Daar JH, Rowsey KE. Trends in behavior-analytic gambling research and treatment. The Behavior Analyst. 2015;38(2):179–202. doi: 10.1007/s40614-015-0027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Wilson AN, Whiting SW. A preliminary investigation of relational network influence on horse-track betting. Analysis of Gambling Behavior. 2012;6(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hoon A, Dymond S, Jackson JW, Dixon MR. Contextual control of slot-machine gambling: Replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41(3):467–470. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Hwang I, LaBrie R, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Winters KC, Shaffer HJ. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(9):1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill, T. R., & Levin, J. R. (2014). Single-case intervention research: Methodological and statistical advances. American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14376-000

- Ladouceur R, Mayrand M, Tourigny Y. Risk-taking behavior in gamblers and non-gamblers during prolonged exposure. Journal of Gambling Behavior. 1987;3(2):115–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01043450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144(9):1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North American Foundation for Gambling Addiction Help. (2016). Statistics of gambling addiction 2016. Retrieved from http://nafgah.org/statistics-gambling-addiction-2016

- Olive ML, Franco JH. (Effect) size matters: And so does the calculation. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2008;9(1):78–86. doi: 10.1037/h0100642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. About behaviorism. New York: Knopf; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherly JN, Dixon MR. Toward an integrative behavioral model of gambling. Analysis of Gambling Behavior. 2007;1(1):4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Welte JW, Barnes GM, Tidwell MCO, Hoffman JH, Wieczorek WF. Gambling and problem gambling in the United States: Changes between 1999 and 2013. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2015;31(3):695–715. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9471-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson,A. N., & Dixon, M. R. (2014). Derived rule tacting and subsequent following by slot machine players. The Psychological Record, 65, 13–21. 10.1007/s40732-014-0070-7

- Wilson AN, Grant T. Implications of derived rule following of roulette gambling for clinical practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(1):52–56. doi: 10.1007/s40617-014-0029-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, L., & Austin, J. L. (2008). Investigating illusion of control in experienced and non-experienced gamblers: Replication and extension. Analysis of Gambling Behavior, 2(1),12–24.

- Zlomke KR, Dixon MR. Modification of slot-machine preferences through the use of a conditional discrimination paradigm. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39(3):351–361. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.109-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]