Abstract

Bidirectional naming (BiN) is the integration of speaker and listener responses, reinforced by social consequences. Unfortunately, these consequences often do not function as reinforcers for behavior in children with autism. Accordingly, the repertoire of BiN is also often limited in these children. Previous research has suggested that so-called multiple-exemplar instruction, a rotation between different speaker and listener operants, may be necessary to establish BiN. The present experiment aimed to investigate whether sequential operant instruction might also work as a successful intervention to improve BiN skills after the establishment of standard social reinforcers. Standard social reinforcers were identified and established through an operant-discrimination training procedure in 4 participating children with an autism spectrum diagnosis. In the present experiment, all participants showed increased BiN after sequential operant instruction with conditioned social reinforcers contingent on relevant operants. Two of 4 participants acquired BiN skills. Moreover, the remaining 2 participants scored within the mastery criterion on listener responses, and 1 of them also met the criterion on the tact probes. Essential characteristics of an intervention, as well as the role of the echoic in the emission of BiN, are discussed.

Keywords: bidirectional naming, conditioned reinforcement, autism, operant-discrimination training procedure, multiple-exemplar instruction, sequential operant instruction

Naming is a technical term for a pattern of interacting responses that a listener may engage in when first encountering the common name of an object. These responses include a cycle of orienting responses, overt or covert echoics to the verbal stimulus, and discriminated operants to the object itself in a period of engagement determined by ambient motivating operations. The concept of naming was first introduced by Horne and Lowe (1996), and at least three basic characteristics of naming have been emphasized. First, if a child is taught to respond as a listener, such as by pointing to a cat when asked where the cat is, corresponding speaker responses, such as saying “cat” in the presence of a cat, will occur without additional training. Second, if a child is taught a verbal response, the corresponding listener response will emerge. Third, from just observing a tact, the child can respond appropriately both as a speaker and as a listener (e.g., Greer & Longano, 2010; Horne & Lowe, 1996; LaFrance & Miguel, 2014; Longano & Greer, 2015). To distinguish the concept of naming from merely tacting an object or event, the term bidirectional naming (BiN) has been proposed (Miguel, 2016) and will be used here.

In typically developing children, a “language explosion” or a “vocabulary spurt” occurs around 18 months of age (e.g., Benedict, 1979; Woodward, Markman, & Fitzsimmons, 1994), the point at which BiN commonly emerges (Horne & Lowe, 1996). The acquisition of BiN appears to be the foundation for the fact that language skills in children expand exponentially from incidental observation. Unfortunately, children with autism often lack BiN skills (e.g., Greer & Longano, 2010; LaFrance & Miguel, 2014). Therefore, effective intervention is essential.

Horne and Lowe (1996) provided an account of how BiN can emerge from an environmental history. During much of an infant’s waking hours, caregivers tact what the infant is looking at or direct the infant’s attention to relevant objects when tacting them. The child orients by turning his or her head in accord with the parents’ pointing or gaze direction. Such episodes exemplify a child responding to a joint attention bid (Whalen & Schreibman, 2003). Through multiple exemplars, the child learns to orient toward and to look specifically at objects or events that a caregiver is looking at or pointing to (Baldwin, 1991). After many repetitions, the caregiver’s tacts alone may begin to occasion orienting toward the corresponding objects. Next, commonly, the child learns to echo the word vocalized by their caregivers (Horne & Lowe, 1996). According to Horne and Lowe (1996), the echoic is a critical component of BiN because it allows for listener relations to expand into speaker relations. When the parents point to and tact dogs in the child’s presence, the parents’ behavior may initially evoke the child’s vocal response “dog” as an echoic. However, when typically uttered in the presence of dogs, “dog” may become a tact under the stimulus control of dogs. Finally, the relevant motivation to respond to the object in question is important. For example, it may be easier to learn the names of dinosaurs than those of chemical compounds.

Horne and Lowe’s model describes a history of reinforcement of essential operants within BiN where each of them is considered to be a prerequisite (Byrne, Rehfeldt, & Aguirre, 2014; Greer, Pohl, Du, & Moschella, 2017; Horne & Lowe, 1996; Miguel, 2016). Three elementary operants are identified: listener responses, echoics, and tacts (Byrne et al., 2014; Catania, 2013; Greer & Longano, 2010; Greer & Ross, 2008; Horne & Lowe, 1996; Miguel, 2016, 2018).

Greer et al. (cf. Greer et al., 2017) have identified at least three types of procedures that have been demonstrated to establish BiN in children who have not shown such skills prior to the intervention: (a) multiple-exemplar instruction (MEI; Fiorile & Greer, 2007), (b) the intensive tact protocol (ITP; Greer & Du, 2010; Pereira-Delgado & Oblak, 2007; Pistoljevic & Greer, 2006; Schauffler & Greer, 2006; Schmelzkopf, Singer-Dudek, & Du, 2017), and (c) conditioning stimuli as reinforcers for observing responses (Longano & Greer, 2015).

MEI involves an environmental history of differential reinforcement where training involves rotation between operants such as echoics, listener responses, and tacts to each stimulus (Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Gilic & Greer, 2011; Greer & Longano, 2010; Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer, Stolfi, Chavez-Brown, & Rivera-Valdes, 2005; Greer, Stolfi, & Pistoljevic, 2007; Holth, 2017; LaFrance & Tarbox, 2019; Nuzzolo-Gomez & Greer, 2004). Rather than teaching echoics separately, Greer and colleagues (e.g., Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Gilic & Greer, 2011; Greer & Longano, 2010; Greer & Ross, 2008; Greer et al., 2005; Greer et al., 2007) have usually provided opportunities for echoic responses during matching-to-sample (MTS) in which the researcher tacts the sample stimulus. This training of intermixed operants may recap the history of differential reinforcement that Horne and Lowe (1996) described as resulting in BiN. If MEI facilitates generativity in language, such as between listener and speaker responses (cf. BiN), it might be particularly beneficial for participants who lack BiN skills (LaFrance & Tarbox, 2019). Research on such rotation across different operants (i.e., MEI) as a successful intervention to establish BiN skills has been extensively replicated (e.g., Byrne et al., 2014; Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Gilic & Greer, 2011; Greer & Du, 2015a; Greer et al., 2005; Greer et al., 2007; Hawkins, Kingsdorf, Charnock, Szabo, & Gautreaux, 2009; Olaff, Ona, & Holth, 2017; Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Lovett, 2011). Only a few experiments have failed to replicate the effectiveness of MEI (e.g., Lechago, Carr, Kisamore, & Grow, 2015; Sidener et al., 2010).

Further, Greer et al. (2007) compared such MEI training with what they called single-exemplar instruction (SEI). In SEI, rather than being intermixed or rotated, the different BiN operants are trained sequentially. Greer et al. (2007) first completed MEI with the experimental group until the mastery criterion was achieved. Then, they introduced SEI for the control group in which the number of trials taught with each operant included in BiN was yoked to the number of trials with the criterion for MEI. Hence, the extent to which each of the primary operants in BiN (i.e., echoics, listener responses, and tacts) were actually established during the sequential training is not clear. Likewise, whether the social consequences contingent on BiN operants functioned as reinforcers was not reported. Moreover, echoics were neither explicitly trained nor identified as an essential prerequisite skill.

SEI may resemble discrete-trial teaching (DTT; e.g., Eikeseth, Smith, & Klintwall, 2014), in which operants are trained sequentially, rather than in rotation. In fact, DTT is a common teaching procedure in early intensive behavioral intervention where responses are first trained in isolation (e.g., listener responses). Next, when a predetermined mastery criterion is obtained, the responses are intermixed within the same class of responses (e.g., listener responses). When one operant class is well established, training on the next operant is introduced in the same manner. DTT, including both simple and conditional discriminations, is a well-documented procedure to establish novel behavior (e.g., Eikeseth et al., 2014; Ghezzi, 2007; Smith, 2001). Because BiN failed to emerge as a product of such sequential operant instruction, Greer et al. (2007) concluded that the rotation involved in MEI was necessary to establish BiN skills. However, we have not found any replications of the study by Greer et al. (2007) that support their suggestion that such sequential instruction does not contribute to the acquisition of BiN.

A second intervention that has improved BiN skills is an ITP (Greer & Du, 2010; Greer et al., 2017; Pistoljevic & Greer, 2006). During this procedure, at least 100 tact trials were trained and added to the ordinary instructional trials. Following ITP, Pistoljevic and Greer (2006) showed that mands and tacts increased in noninstructional settings.

The third procedure that has been found to enhance BiN skills is the pairing of visual and auditory stimuli, in which the one that functions as the reinforcer is paired with the neutral stimulus. That is, for example, if visual stimuli are assumed to function as conditioned reinforcers, these stimuli are then paired with the auditory stimuli (i.e., the spoken common name of the stimuli). Longano and Greer (2015) conditioned visual and auditory stimuli as reinforcers to reinforce observing responses to evoke echoics to establish BiN. Observing responses are operants reinforced by the clarification of discriminative stimuli (SDs) for other behavior (cf. Donahoe & Palmer, 1994; Pierce & Cheney, 2008; Wyckoff, 1952). An example of an observing response is pressing the space bar on a computer to clarify a visual and spoken SDs, such as a photo of a dog while the speaker on the computer presents the spoken word dog. In all three participating children with autism and developmental disability, BiN emerged as a result of conditioning visual and auditory stimuli as reinforcers for observing responses (Longano & Greer, 2015).

Similar procedures, which also consist of pairing visual and auditory stimuli, are pairing naming and the stimulus-pairing observation procedure (SPOP). The difference between pairing naming and SPOP is in the probing of BiN which occurs after the exposure to the novel stimuli (i.e., stimulus-stimulus pairing, SSP). Pairing naming exposes the participants to novel tacts until these tacts emerge and then probes manded tacts and listener responses (e.g., Pérez-González, Cereijo-Blanco, & Carnerero, 2014), whereas SPOP probes both listener responses and tacts after the exposure phase (e.g., Byrne et al., 2014; Rosales, Rehfeldt, & Huffman, 2012; Solares & Fryling, 2018). In a study reported by Carnerero and Pérez-González (2014), all four participating children with autism showed BiN after exposure to the pairing naming procedure, and in Solares and Fryling (2018), listener responses and tacts consistent with BiN appeared in all three participating children with autism after their SPOP intervention.

Longano and Greer (2015) emphasized that visual and auditory stimuli have to be conditioned as reinforcers for observing responses to evoke echoics to join speaker and listener responses. Neither pairing naming nor SPOP involved any focus on the establishment of observing responses. Instead, both SPOP and pairing naming included responding to instructions (e.g., “Look at the screen,” or “Look at the photo.”) that likely clarified the relevant SDs and thereby, unintentionally, trained observing responses.

It is difficult to determine the specific importance of the clarification of an SD as a conditioned reinforcer for observing responses (e.g., Cao & Greer, 2019; Longano & Greer, 2015). It is possible that establishing the word sound and the visual stimulus relevant to a particular tact as conditioned reinforcers will strengthen not only the potential observing responses but also the discriminative control by those stimuli over other behavior (e.g., echoics and tacts).

Based on the research reported previously, interventions that have been shown to improve BiN skills may share certain characteristics. The common characteristics of interventions that improve BiN skills thus far seem to be (a) the strengthening of an echoic repertoire, (b) the use of natural social conditioned reinforcers for all BiN operants, and (c) some sort of sharpening of control by the purported SDs for the BiN operants, through either explicit observing responses or directly differential reinforcement. Moreover, all interventions depend on motivating operations for listener and speaker responses to the stimuli included. However, the relative importance of each of these on the establishment of BiN skills is not clear. Besides, sequential operant instruction may involve all these factors, possibly without being sufficient to produce BiN skills. However, essential factors missing from sequential operant instruction have not been identified (cf. Greer et al., 2007).

Although Horne and Lowe (1996) proposed that the echoic is necessary to integrate listener and speaker responses, the role of the echoic is unclear in MEI, as well as in sequential training, because echoic skills are usually not directly trained. Only a few studies have required echoics in the matching trials during MEI (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2009; Olaff et al., 2017). In contrast, Greer and colleagues (e.g., Fiorile & Greer, 2007; Gilic & Greer, 2011; Greer et al., 2005; Greer et al., 2007) have commonly not required echoics during MEI and SEI, nor during the exposure to novel stimuli before the BiN probes (i.e., MTS tasks with the researcher’s tact of the novel sample stimuli).

Greer et al. (2007) speculated that the rotation of the BiN operants, which characterized MEI, was necessary for the establishment of BiN. However, the findings of Pistoljevic and Greer (2006), Longano and Greer (2015), Carnerero and Pérez-González (2014), and Solares and Fryling (2018)—that BiN was acquired in the absence of MEI—strongly suggests that such rotation between BiN operants is not necessary. Furthermore, the establishment of observing responses to clarify relevant SDs does not seem to be necessary: MEI, sequential operant instruction, and ITP involve discrimination training and therefore likely strengthen discriminative control by the relevant antecedents for echoics, tacts, and listener responses.

Regardless of the other common characteristics of procedures shown to improve BiN, the sources of reinforcement for all BiN operants are social. In the natural environment, typical social consequences, such as others’ comments, nods, and smiles, must reinforce the responses. Hence, the conditioning of essential social stimuli as reinforcers for the addressed operant is fundamental for the acquisition and maintenance of complex social behavior (cf. Greer & Du, 2015b). Unfortunately, the relevant social stimuli often may not function as reinforcers for behavior in children with autism (e.g., Gale, Eikeseth, & Klintwall, 2019; Jones & Carr, 2004; Rodriguez & Gutierrez, 2017; Shillingsburg, Hollander, Yosick, Bowen, & Muskat, 2015). Therefore, an effective means to condition social consequences as reinforcers may be an essential part of successful intervention procedures.

Longano and Greer (2015) employed an SSP procedure in order to condition reinforcers. In contrast, other experiments have suggested that an operant-discrimination training (ODT) procedure may be more promising for the establishment of conditioned reinforcers (e.g., Holth, Vandbakk, Finstad, Grønnerud, & Sørensen, 2009; Isaksen & Holth, 2009; Keller & Schoenfeld, 1950; Lepper, Petursdottir, & Esch, 2013; Lugo, Mathews, King, Lamphere, & Damme, 2017; Olaff, 2012; Taylor-Santa, Sidener, Carr, & Reeve, 2014; Vandbakk, Olaff, & Holth, 2019). The ODT procedure involves establishing an SD for a response that produces the unconditioned or already-conditioned reinforcer (e.g., Vandbakk et al., 2019). The SD sets the occasion for a response (e.g., the child moving his or her hand into a box to grab an item) that produces the reinforcer, thereby making sure that the participant responds to the antecedent stimulus (e.g., Holth, 2005; Isaksen & Holth, 2009; Lepper et al., 2013; Taylor-Santa et al., 2014). The ODT procedure has been shown to establish social reinforcers to improve significant complex behavior successfully. Examples are joint attention in children with autism (e.g., Isaksen & Holth, 2009; Olaff, 2012), early vocalization in infants (e.g., Lepper et al., 2013), and the establishment of social stimuli as reinforcers (e.g., Lovaas et al., 1966; Lugo et al., 2017; Taylor-Santa et al., 2014).

Despite the lack of direct empirical evidence, an echoic repertoire may be an essential prerequisite for BiN, but there may be additional prerequisites, such as that standard social consequences of behavior are effective as reinforcers. In the current study, we identified children with an echoic word repertoire but no BiN and whose behavior was not reinforceable by standard social consequences at the beginning of the experiment. The primary research question was whether the establishment of standard generalized conditioned reinforcers might suffice to make the sequential operant instruction work to establish BiN in children with autism and with an already-established echoic repertoire. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present experiment is the first to investigate whether the establishment of standard conditioned social reinforcers can facilitate the acquisition of BiN skills. In addition, we assessed whether the number of emerged BiN operants correlated with the number of echoics that were emitted without being required during the exposure to researcher-presented novel tacts.

Method

Participants

Four boys between 4 and 5 years old who were diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder or pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified participated in the current study. The four children attended different public day care centers, where two of them received early intensive behavior intervention for approximately 25 hr per week, whereas the remaining participants received 1–3 hr of weekly language and play training based on applied behavior analysis.

The prerequisites required for participation in the present study were MTS skills of visual 2-D stimuli and compliance with teachers’ instructions while working at a table for 2–5 min. A third requirement was that the operants included in BiN were demonstrated: 20–50 echoics of words occurred spontaneously, 20–50 listener responses (“Point to…”), and 20–50 tacts and manded tacts, which are controlled by a nonverbal stimulus in conjunction with the question “What is this?” (Michael, Palmer, & Sundberg, 2011). Participants who demonstrated BiN on the first probe were excluded. The participants’ language skills were initially assessed by the Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills–Revised (ABBLS-R; Partington, 2006), and the percentage of domains mastered for each participant is presented in Table 1. The study was approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data.

Table 1.

Description of the Participants According to Age, Diagnosis, and ABLLS-R Scores

| Participants | Age Year: Months |

Diagnosis | ABLLS-R Scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glen | 4:10 | Autism |

- Cooperation and reinforcer effectiveness (A): 71% - Visual performances (B): 56% - Receptive language (C): 25% - Vocal imitation (E): 16% - Requests (F): 24% - Labeling (G): 14% - Intraverbals (H): 2% - Spontaneous vocalization (I): 7% - Syntax and grammar (J): 0% - Generalized responding (P): 25% |

| Hans | 5:4 | Autism |

- Cooperation and reinforcer effectiveness (A): 77% - Visual performance (B): 86% - Receptive language (C): 74% - Vocal imitation (E): 38% - Requests (F): 70% - Labeling (G): 64% - Intraverbals (H): 31% - Spontaneous vocalization (I): 100% - Syntax and grammar (J): 45% - Generalized responding (P): 75% |

| Mark | 5:8 | Pervasive developmental disorder–not otherwise specified |

- Cooperation and reinforcer effectiveness (A): 77% - Visual performance (B): 86% - Receptive language (C): 74% - Vocal imitation: (E) 38% - Requests (F): 70% - Labeling (G): 64% - Intraverbals (H): 31% - Spontaneous vocalization (I):100% - Syntax and grammar (J): 32% - Generalized responding (P): 92% |

| Alan | 5:0 |

Autism Mild intellectual disability |

- Cooperation and reinforcer effectiveness (A): 60% - Visual performance (B): 30% - Receptive language (C): 83% - Vocal imitation (E): 95% - Requests (F): 89% - Labeling (G): 52% - Intraverbals (H): 14% - Spontaneous vocalization (I): 96% - Syntax and grammar (J): 85% - Generalized responding (P): 83% |

Note. Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills–Revised (ABLLS-R) is summarized as the percentage achievement per skill areas at intake in the experiment. The skill domain Labeling (G) is considered to be the tact repertoire. Receptive language (C) is the listener repertoire, and echoics are vocal imitation skills (E)

Setting and Materials

The present experiment was completed in the participants’ teaching rooms in their day care centers. The researcher and the participant sat opposite each other at a table. In addition to the researcher, the responsible special education teacher was present. All teaching days and sessions were 1–2 hr in duration, including breaks and setting and cleaning up materials. Sessions were conducted 2–4 days weekly for approximately 6–8 weeks. One BiN probe took 30–45 min, whereas one test of conditioned reinforcers lasted for approximately 1–2 days. The ODT procedure lasted 3–5 teaching days, whereas sequential operant instruction took 3–8 days.

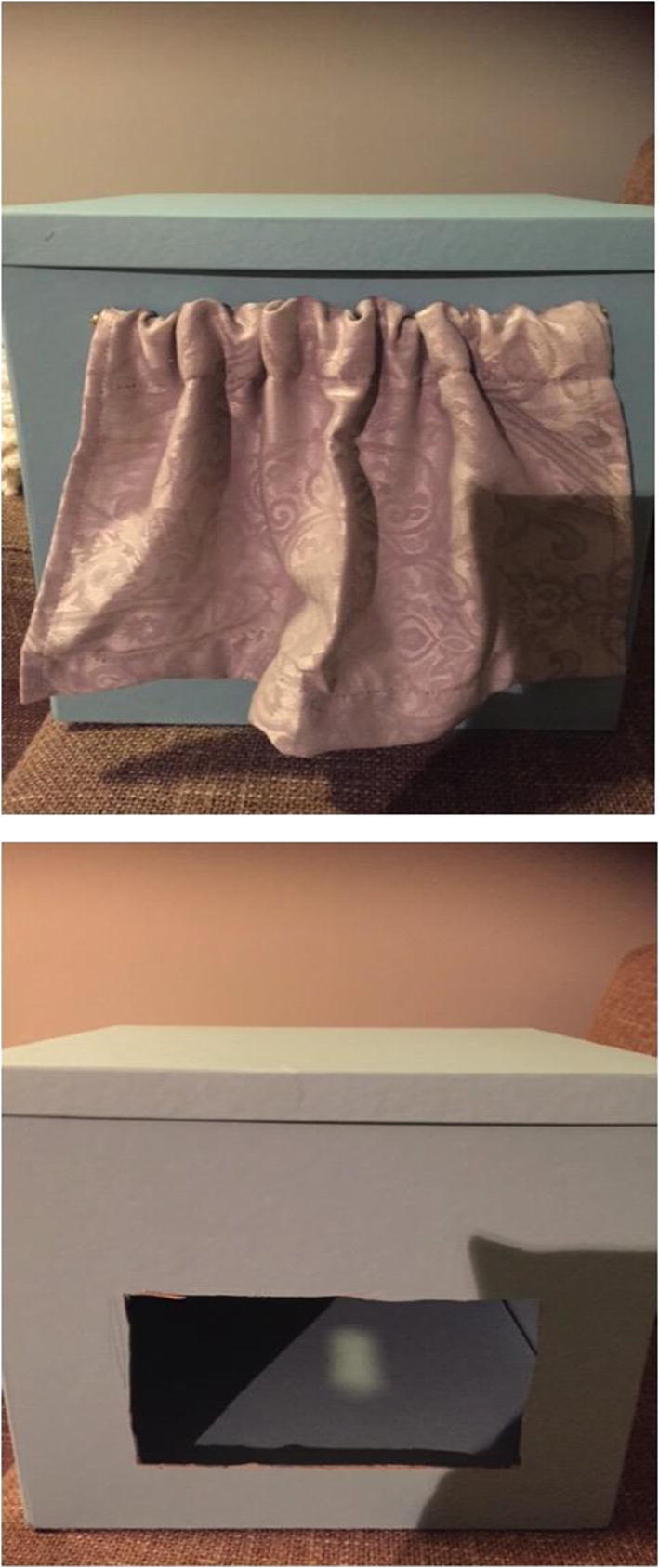

A D5100 SLR camera and a 13-in (33.02 cm). MacBook Air were used for Glen and Hans, and a 15-in (38.1 cm). MacBook Pro was used for Alan and Mark, with a 13-GHz Intel Core i5 processor and the OS X Yosemite, Version 10.10.5, operating system. During the presentation of novel tacts, Microsoft PowerPoint for Mac 2011, Version 14.5.6, was used. During the probes of BiN and sequential operant instruction, laminated photos of novel stimuli (7 cm × 5 cm) were used. Novel stimuli were stimuli to which a participant emitted no overt responses as speaker or listener. An example of a stimulus set is provided in Table. 2. In addition, a “reinforcer box” (32 cm × 35 cm × 32 cm) was used during the conditioning phase in order to avoid discriminative control by visible primary reinforcers. The box was a hard cardboard box (from IKEA) with squares cut out in the front and the back. The front opening was covered by a curtain, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Table 2.

An example of stimuli used during the experiment

Fig. 1.

Photos of the reinforcer box used during operant-discrimination training sessions. The curtain side was facing the participant, whereas the open side was facing the researcher. The photos were taken by the first author

Design

A within-subject research design was used. The design consisted of pre- and post-BiN probes and a generalization BiN probe. Tests of BiN were completed before and after two types of interventions: first, conditioning of reinforcers and, next, sequential operant instruction involving making these consequences contingent on instances of the operants included in BiN. During baseline, BiN probes were carried out at least twice to demonstrate that BiN skills did not increase solely as a function of repeated exposure to others’ tacts. If BiN skills increased during baseline, the baseline was extended until the scores stabilized. Moreover, the differences in the number of baseline sessions gave the experimental design the essential features of a multiple-baseline design across participants. Before and after conditioning of social stimuli, a test of conditioned reinforcers was completed.

Dependent and Independent Variables

The primary dependent variable was BiN skills, such as pointing to teacher-tacted objects (the listener component of BiN), tacts, and manded tacts (the speaker component of BiN). During the reinforcer-conditioning procedure, the dependent variable was lifting the box-front curtain and accessing the contents of the box contingent on a teacher-presented smile, nod, praise, or a relevant affirmative comment.

Data Collection

Data were recorded with pencil and prepared data sheets, both in vivo and by observing video clips of trial blocks. The dependent variables were measured as the number of correct responses. A plus (+) for correct responses and a minus (−) for incorrect or no responses were recorded. All probes and training blocks consisted of 20 trials. The responsible special education teacher, if present, independently recorded responses for later calculation of reliability. All test trial blocks of conditioned reinforcement—as well as random probe trial blocks of BiN, ODT, and sequential operant instruction—were videotaped for later reliability scoring.

Procedure

In a preliminary investigation, we identified common social consequences delivered by parents when typically developing children emit BiN skills. The social stimuli were categorized into three groups: (a) praise (e.g., “Fine,” “Good,” “Super.”), (b) acknowledgment or relevant comments (e.g., “Yes,” “That’s right,” “Sure, that’s Elsa.”), and (c) gestures (e.g., smiles and nods). Both the mother’s and the father’s behavior were assessed in order to identify common consequences on BiN skills. In the preliminary investigation, a total of eight parents and six typically developing children were included. However, none of these children participated in the main experiment.

The procedure in the preliminary examination was based on naming by exclusion (cf. Greer & Du, 2015a). Each child received five trials. In each trial, the parent presented five pictures or photos of cartoon characters, four of them familiar (e.g., Donald Duck, Winnie the Pooh, Cinderella, and Elsa) and one novel (e.g., the Polish-French character Colargol and the Norwegian characters Pompel, Pilt, Pernille, and Mr. Nelson). The parent and the child sat on the floor, and the parent told the child that they were going to look at some pictures. First, a listener trial with the familiar stimulus was presented, then a tact trial, and, finally, a manded tact trial with the same cartoon character. The adult placed, for example, pictures of Donald Duck, Winnie the Pooh, Cinderella, Elsa, and Colargol on the floor between them. Then the parent asked the child, “Where is [a familiar cartoon character]?” (e.g., “Where is Elsa?”). When the child emitted a correct response, the adult held up the picture in front of the child to induce a tact (e.g., “Elsa.”) and, finally, asked, “Who is this?” (the manded tact). The child replied, for example, “Elsa.” During these trials, the parents were instructed to deliver feedback they felt natural, and they were free to prompt correct responses as they usually did. The four trials with familiar cartoon characters were implemented accordingly. In the fifth trial, the novel stimulus was presented, and the child was asked to identify it (e.g., “Where is Colargol?”). Given that he was able to identify and tact the familiar cartoon characters, he was also likely able to exclude the known stimuli and pick the unknown (e.g., he or she pointed to the picture of Colargol). Then, the adult presented a tact trial by holding up the unknown stimulus, and the child responded, for example, “Colargol.” Finally, the parent initiated a manded tact trial by asking, “Who is it?” The child answered by saying, “Colargol.”

Praise statements, acknowledgments, and gestures were counted across parents to identify the most frequent consequences. If a social stimulus occurred three times or more, it was selected for conditioning in the main experiment. The social stimuli thus identified for conditioning are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Social Stimuli Identified and Conditioned

| Praise | Acknowledgments | Gestures |

|---|---|---|

| So clever. | Yes. | Nods and smiles |

| Yes, great. | Yes, that is correct. | |

| Now, you were good. | Did you know that? | |

| Yes, enormously good. | Mm-hmm. | |

| Yes, very good. | Yes, that’s right. | |

| Super. | That’s it. | |

| Fantastic. | Right. | |

| You can do this. | There you go. | |

| Very good. | Just right. | |

| Enormously great. | Yes, it is absolutely right. |

Before the implementation of the main procedure, responding to instructions presented by a computer was tested. All participating children either responded to these instructions immediately or after a few trial blocks. Examples of instructions were (a) pointing to a familiar object (e.g., “Point to cauliflower.”), (2) a simple direction (e.g., “Clap hands.”), and (3) questions such as “What is this?” when presenting a picture of a familiar object (e.g., a train). Table 4 provides an overview of the main experiment sequences and phases of the following procedure.

Table 4.

Experimental Sequence

| Phases | Tests (Probes) | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identification of novel stimuli | |

| 2 | Pretest of conditioned reinforcers | |

| 3 | Baseline BiN probes with Set 1 stimuli | |

| 3a | Exposure to novel stimuli: probes of BiN, Part 1 | |

| 3b | Baseline BiN probes, Part 2 | |

| 4 |

Intervention 1: Establishment of social consequences as positive reinforcers through an operant-discrimination training procedure |

|

| 5 | Posttest of conditioned reinforcers, as Phase 2 | |

| 6 |

Intervention 2: Sequential operant instruction with Set 2 stimuli |

|

| 7 | Post-BiN probe, Set 1 stimuli, conducted as Phases 3a and 3b | |

| 8 | Generalization BiN probes with Set 3 stimuli, conducted as Phases 3a and 3b |

Phase 1: Identification of novel stimuli

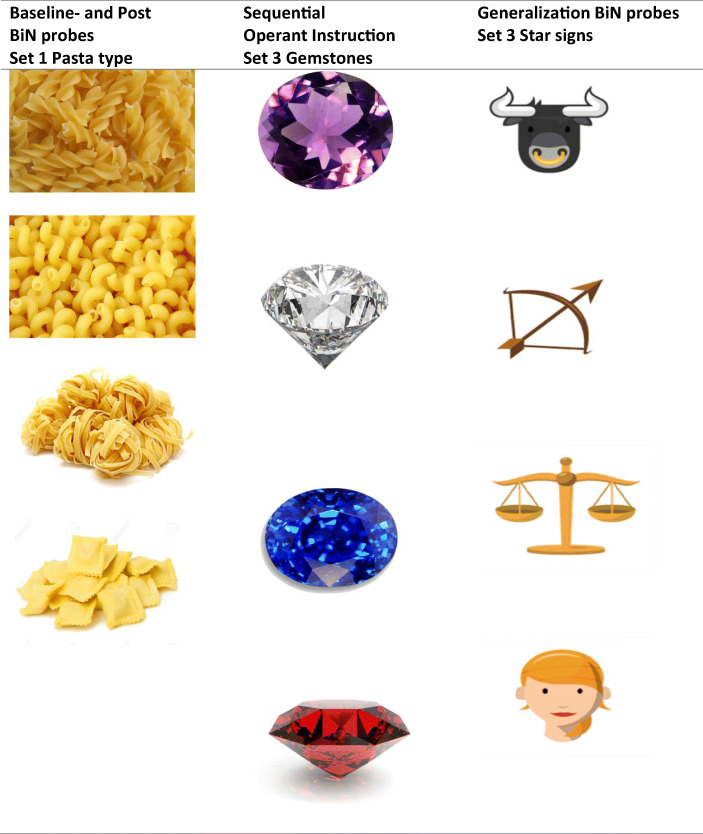

The purpose of this phase was to identify three sets of four novel stimuli (see Table 2 for an example). Set 1 contained photos of pasta types and was used during the baseline and the post-BiN probes, whereas Set 2 consisted of photos of gemstones and was reserved for the sequential operant instruction. Set 3 was star signs and was used for the generalization probe, only conducted once to measure generalization of BiN to novel stimuli.

Each test trial was repeated three times across the BiN operants: tacts, manded tacts, and listener responses. During tests of tacts and manded tacts, the stimuli were held up in front of the participant, and a pointing prompt was used to ensure the participant attended to the stimuli. When manded tacts were probed, the vocal antecedent “What is this?” was presented along with the nonverbal SD. During testing of listener responses, the four stimuli included in the set were placed in an array on the table, and the researcher gave the instruction “Point to [object name],” or asked, “Where is [object name]?”

If no correct tact, manded tact, or listener response occurred within 6 s, the trial was scored as incorrect. However, if the participant tacted a stimulus correctly, that particular stimulus was excluded from the set. No prompting or error correction was provided during probing. During the test of listener responses, one correct response of three was considered as chance. Only neutral feedback was offered during the test: For example, the researcher said, “OK,” “Yes,” or “Mm-hmm” regardless of the accuracy of the participants’ responses. Mastered tasks were interspersed between test trials, every third to fifth trial, and correct responses were differentially reinforced by identified preferences along with praise.

Phase 2: Pretest of conditioned reinforcers

The test of conditioned reinforcers was based on Holth et al. (2009) and Olaff (2012). A free operant setting was arranged. That is, no particular antecedent was presented, the arbitrary responses (e.g., pointing to his or her nose) were manually prompted, and then preferred stimuli (e.g., ice cream) were presented contingent on the identified responses. The reinforcer test was arranged according to a standard definition of reinforcement (e.g., Catania, 2013). Preferences were identified by the use of the multiple-stimulus without-replacement procedure until at least 10 preferences were identified (DeLeon & Iwata, 1996). Examples of preferred stimuli identified were toys such as a basketball net and ball, a fan, slime, a parachute man, a microphone, an iPad, and cell phones. In addition, edibles were identified as preferences, such as crackers, potato chips, ice cream, Coca-Cola, and grapes. The preferred items were used during the test of conditioned reinforcers, the ODT procedure, and contingent on the mastered interspersed trials.

The test of conditioned reinforcers consisted of three conditions: (a) no programmed consequences (testing for possible automatic reinforcement), (b) presentation of standard presumptive social reinforcers, and (c) presentation of preferred tangible stimuli. For each test response (arbitrary response), the test conditions were always presented in the same order. This sequence was selected with the goal of obtaining extinction during the no-consequence condition and then demonstrating a possible effect of social consequences. The objective of the tangible consequences condition was to increase the rate of responding before the next arbitrary response was tested. In order to avoid carryover effects from the social stimulus condition and tangible condition, every new arbitrary response was initially exposed to the no-consequence condition. The social reinforcement condition was not introduced until extinction was achieved during the no-consequence condition. In the third condition, preferred tangible stimuli were contingent on the emission of neutral responses. The participants had access to the stimuli for 3–5 s.

Six arbitrary responses were randomly selected. Table 5 describes each of the six arbitrary responses, Response (R) 1–6. R1 to R3 were used during the pretest, and R4 to R6 were used during the posttest. The test of conditioned reinforcers was conducted according to the description of the new response technique (Kelleher & Gollub, 1962). That is, the stimuli included in the test conditions were delivered contingently on the emission of one of the six arbitrary responses. Each test condition lasted for a maximum of 3 min but was terminated if 30 s passed without a response.

Table 5.

Identification of Arbitrary Test Responses

| Participant | Responses (Pretest) | Duration (Ca.) | Responses (Posttest) | Duration (Ca.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glen |

R1: Touch the square R2: Touch the floor with one hand R3: Stand up from the chair |

0.5 s 2.0 s 1.0 s |

R4: Hands up R5: Clap hands once R6: Hands in lap |

1.0 s 0.5 s 1.0 s |

| Hans |

R1: Hands in lap R2: Hands up R3: Clap hands once |

1.0 s 1.0 s 0.5 s |

R4: Match the red teddy bear and the red diamond R5: Put two Duplo blocks together R6: Put a 3-D car on a 2-D car |

1.0 s 1.0 s 1.5 s |

| Alan |

R1: Stand up from the chair R2: Touch the floor with one hand R3: Touch the circle |

1.0 s 2.0 s 0.5 s |

R4: Touch top of head R5: Clap hands once R6: Touch belly with one hand |

1.5 s 0.5 s 1.0 s |

| Mark |

R1: Touch the floor with one hand R2: Stand up from the chair R3: Sit down on the floor and get up |

1.0 s 1.0 s 3.0 s |

R4: Clap hands once R5: Hands on shoulders R6: Hands on opposite feet |

0.5 s 1.0 s 1.0 s |

Note. The table shows an overview of the identified neutral responses and the approximate duration of the responses. The responses were further used during the test of conditioned preferences. R = response

Initially, the participants were told that they could do what they wanted but were not allowed to leave the teaching room. Then the arbitrary response was prompted by the researcher using manual guidance across two to three trials. Responses were considered to not produce automatic reinforcement if rapid extinction occurred after the prompted trials. The extinction outcome was defined as a lack of responding during the last 30 s of the test condition or by the participant leaving the chair. If high-frequency responding occurred during the test, a different response was selected. A 2- to 3-min break was given between each test condition.

In the following condition, social stimuli identified during the preliminary investigation (i.e., praise, nods, smiles, or acknowledgments) were contingent on the emission of arbitrary responses. During the pretest of social stimuli, R1 produced praise for Glen and Hans and nods and smiles for Alan and Mark, respectively. R2 produced nods and smiles for Glen and Hans and praise for Alan and Mark, respectively. Finally, R3 produced relevant comments or acknowledgments for all participants.

The social conditions were arranged such that only one type of social stimulus was delivered at a time. For example, R1 was first tested for automatic reinforcement over a 3-min period, then followed by social stimuli for a 3-min interval, and in the last 3-min interval, the emission of R1 resulted in tangible stimuli. During the posttest, the remaining arbitrary responses (R4–R6) were assessed accordingly. For each participant, the social consequences were presented in the same order as in R1–R3.

Phase 3: Probes of Bidirectional Naming

Phase 3a: Pre-training, exposure to novel tacts

During this phase, the participants were exposed to sound recordings of novel tacts and corresponding objects, as identified during Phase 1 (identification of novel stimuli). Set 1 stimuli were presented on the computer screen in a PowerPoint presentation. The researcher oriented the participant to the computer, where photos of novel stimuli were presented, one by one. The four stimuli in each set were presented five times, in different random sequences, constituting a 20-trial block. Photos were presented on the screen for a duration of 2 s before a sound recording dictating the names of the objects (i.e., auditory stimuli) was presented. Following the presentation of the auditory stimulus, the photos remained on the screen for an additional 4 s. The sound recordings consisted of the researcher’s voice tacting the item presented on the screen. Intertrial intervals (ITIs) were 3 s in duration. During exposure to novel stimuli, no responses were required, and the participants received praise and touch (e.g., soft taps on the shoulder) for looking at the screen and sitting appropriately. If participants echoed the auditory stimuli, this was recorded on a separate data sheet. No programmed consequences were delivered for these responses. Following the completion of this phase, participants were given a 5-min break before the BiN probes (Phase 3b) were conducted.

Phase 3b: Probes of Bidirectional Naming

The probe sequence was (a) listener responses, (b) tacts, and, finally, (c) manded tacts. All probes occurred without differential reinforcement. However, nondifferentiated feedback (e.g., “OK,” “Yes,” or “Mm-hmm.”) was delivered contingent on responses regardless of whether they were correct or not. Stimuli that were identical to those presented in probes of BiN, Part 1, were used, and all operants were probed as in Phase 1 (identification of novel stimuli). If a correct response occurred within 6 s, it was scored as correct, whereas incorrect response or no response within 6 s was scored as incorrect. Regardless of whether the response was correct or incorrect, the participant was exposed to the next trial. During probes of listener responses, the four stimuli presented on the table were rotated between trials. That is, the target stimulus was placed in different positions across trials. Also, probes of tacts and manded tacts were randomly rotated across test trials. One block of BiN probes consisted of 60 trials. That is, 20 test trials were conducted per operant. During baseline, BiN probes were repeated for Set 1 stimuli until a stable trend was achieved. Maintenance tasks were interspersed every third or fifth trial. The mastery criterion for BiN was set to 80% correct responses or higher (at least 16 correct responses out of 20).

Phase 4: Establishment of conditioned social reinforcers (the ODT procedure)

After a stable baseline trend was obtained, the intervention phases were initiated. We used an ODT procedure to establish social stimuli as conditioned reinforcers. During this phase, participants received four to six trial blocks per day. Each trial block consisted of 20 trials.

The participant and the researcher sat on opposite sides of the table with the reinforcer box placed between them, slightly to one side of the table. The reinforcer box was used in all trials and trial blocks during the ODT procedure. The curtain side of the box faced the participant, whereas the side with the open window faced the researcher (see Fig. 1). The purpose of this arrangement was to allow the researcher to put a preferred stimulus in the box without providing any cues of the availability of the unconditioned reinforcer other than the social stimuli to be conditioned as reinforcers. The researcher’s presentation of a social stimulus (SD; see Table 3) set the occasion for the participant to access the contents of the box. That is, the participant pulled aside or lifted the curtain to access the preferred stimulus. For participants with whom token economies were utilized, tokens were placed in the box. In the absence of the researcher's praise, nods, smiles, and comments, responses were not followed by reinforcers (SΔ) Access to the box was blocked by a confederate (usually the special education teacher). The confederate was standing behind the participant and put his or her hands in front of the curtain to prevent the participant from lifting it. In general, the participants were in contact with the SΔ condition in the first two to five trials.

In cases where no target response occurred within 6 s, the trial was scored as incorrect, and the response was prompted by the confederate (behind the participant). Prompts were presented immediately after the SD and were faded out over subsequent trials. If a participant did not lift the curtain on the box following the SD, the response was scored as incorrect and prompted using physical guidance. For all participants, praise was first presented, followed by nods and smiles, and finally acknowledgments. Acknowledgment and praise statements were written down in two different quasi-random sequences, and the two sequences were switched every second trial block.

Initially, every correct response was differentially reinforced by a social stimulus followed by a tangible stimulus behind the curtain. The mastery criterion was met when the participants responded correctly and only in the presence of the SDs for a minimum of 90% of the trials across two consecutive trial blocks or on all trials within one trial block. When the mastery criterion was achieved, the schedule of reinforcement was thinned to a fixed ratio 2 (FR2). The same mastery criterion was used during FR2. Then, the schedule of reinforcement was further thinned to a variable ratio 3 (VR3), where, on average, every third response was reinforced. The final mastery criterion under the VR3 schedule of reinforcement was two trial blocks of 100% correct responding. After the criterion was met under the VR3 schedule of reinforcement, stimuli in the next category of social stimuli were conditioned using the same procedure. The same mastery criterion and thinning sequence of the reinforcement schedules were employed.

Phase 5: Posttest of conditioned reinforcers

A posttest of whether the social stimuli had acquired reinforcing properties was completed. This posttest was completed in the same manner as the pretest of conditioned reinforcers, as described in Phase 2. However, during Phase 5, three other arbitrary responses, R4, R5, and R6, were introduced. The box used during the ODT procedure (Phase 4) was also provided to Alan during the posttest of conditioned social reinforcers because rapid extinction had been observed during thinning of the reinforcement schedule during the ODT procedure.

Phase 6: Sequential operant instruction

The purpose of this phase was to expose the operants that constitute BiN to the conditioned social consequences. No other consequences were delivered. During these trial blocks, the conditioned social reinforcers were contingent on instances of BiN operants. Set 2 stimuli were used, consisting of four gemstones. All operants were trained separately in 20-trial blocks.

First, tacts were established, then manded tacts. Echoics were trained during MTS tasks by pairing matching responses with echoics of the researcher’s tacts of the sample stimuli. Finally, the listener responses were trained. The number of trial blocks completed to establish tacts was yoked to the number of trial blocks conducted for the other operants. The mastery criterion for tacts was two consecutive trial blocks at 90%–100% correct responses.

If the participants did not respond or responded incorrectly, prompts were presented on the next trial. In the speaker trials, an echoic prompt was used. In the listening trials, a gesture (i.e., pointing to the correct stimulus) prompt was provided. After a prompted trial, the same trial type was repeated and prompts gradually faded. This sequence continued until the participants responded independently.

Phase 7: Postprobes of BiN

After both interventions, each participant completed a post-BiN probe. The post probe was conducted with Set 1 stimuli (i.e., the pasta types) using the same procedure as described in Phases 3a and 3b.

Phase 8: Generalization BiN probes

A single generalization probe was conducted with novel stimuli, which consisted of star signs (i.e., Set 3 stimuli). The generalization BiN probe was conducted according to the procedure described in Phases 3a and 3b.

Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Integrity

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was recorded in 30%–47% of the trial blocks, except for the tests of conditioned reinforcement. However, during these tests, random checks of trial blocks were completed by the first author by playing the videotape over again. The response rate was cumulatively scored during the intervals of the different conditions. IOA was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of trials checked in each phase and then multiplied by 100. IOA was 100% during the trial blocks checked for Hans and Glen, 99.6% for Alan, and finally 98.8% for Mark. Across training and probe phases for the four participants, the mean IOA was 99.6%.

Treatment integrity (TI) checks were randomly conducted in at least 30%–84% of the trial blocks. TI was checked in each phase of the experiment for each participant. The procedural components scored for TI consisted of the following: accurate vocal instructions; accurate prompting procedure, such as pointing to the relevant object or event and the position of prompts during MTS and listener trials; and the duration of test intervals during the test of conditioned reinforcers. The TI criterion was a minimum of 90% correct implementation and was calculated by dividing the number of trial blocks completed according to the procedure by the total number of checked trial blocks. Scores obtained ranged from 96% to 100% integrity. During the reinforcer test, two items were adjusted. First, the number of prompted trials was increased from two to three. Second, for Alan, the reinforcer box was present during the test of conditioned reinforcement. In order for Alan to emit responses during the reinforcer test, and thereby demonstrate preference, a VR3 schedule of reinforcement was implemented.

Results

During the test of novel stimuli, up to six stimuli were discarded as familiar because the participant responded with a correct tact or with correct listener responses. Eventually, four novel stimuli were identified within each set for each participant. These were stimuli to which the participant emitted no correct tacts or manded tacts. Also, no pattern of correct listener responses to the stimuli occurred with any of the participants.

During the ODT procedure, praise, smiles and nods, and relevant comments, respectively, were established as SDs in 4–15 trial blocks (see Table 6). Concerning the test of conditioned reinforcers, the number of responses during the social consequence conditions increased from pretest to posttest, as shown in Table 7. Across the three social conditions from pretest to posttest, Hans’s number of responses increased from a mean of 2 during the pretest to a mean of 9.7 responses during the posttest. Glen’s number of responses increased from a mean of 2 during the pretest to a mean of 16.7 responses during the posttest, Alan’s number of responses increased from 3.3 during the pretest to 18.3 during the posttest, and Mark’s number of responses increased from 3.6 during the pretest to 114.7 during the posttest. Across participants, the mean increase in the number of responses was 39.9 during the social conditions, following the conditioning of social stimuli through the ODT procedure (see Table 7). Also, the number of responses increased during the tangible conditions from pretest to posttest, as reported in Table 7. Hans’s number of responses increased from a mean of 3.6 during the pretest to a mean of 8 responses during the posttest, and Glen’s number of responses increased from a mean of 4 responses during the pretest to a mean of 24 responses during the posttest. Further, Alan’s number of responses increased from a mean of 4.3 responses during the pretest to a mean of 64.3 responses during the posttest, whereas Mark’s number of responses increased from a mean of 24.3 responses during the pretest to a mean of 62.3 responses during the posttest.

Table 6.

Number of Operant-Discrimination Training Trial Blocks Until Mastery of Variable Ratio 3 Schedule of Reinforcement

| Participant | Praise | Nods and Smiles | Relevant Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glen | 15 | 9 | 8 |

| Hans | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| Alan | 11 | 12 | 7 |

| Mark | 4 | 5 | 5 |

Note. All trial blocks consisted of 20 trials. Praise and relevant comments were presented in a predetermined random order

Table 7.

Test of Reinforcers

| Conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Consequences | Social | Tangible | Total Mean | |||

| Hans | Pretest | R1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2.3 |

| R2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2.3 | ||

| R3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 3.6 | ||

| Mean R1–R3 | 2.3 | 2 | 3.6 | 2.6 | ||

| Posttest | R4 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 6.6 | |

| R5 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 5 | ||

| R6 | 4 | 13 | 12 | 9.7 | ||

| Mean R4–R6 | 2.7 | 9.7 | 8 | 7 | ||

| Glen | Pretest | R1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| R2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| R3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.3 | ||

| Mean R1–R3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2.7 | ||

| Posttest | R4 | 10 | 15 | 24 | 16.3 | |

| R5 | 2 | 13 | 29 | 14.7 | ||

| R6 | 2 | 22 | 19 | 14.3 | ||

| Mean R4–R6 | 4.7 | 16.7 | 24 | 15.1 | ||

| Alan | Pretest | R1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3.3 |

| R2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3.3 | ||

| R3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3.3 | ||

| Mean R1–R3 | 2. 3 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 3.3 | ||

| Posttest | R4 | 3 | 12 | 77 | 30.7 | |

| R5 | 3 | 23 | 61 | 29 | ||

| R6 | 3 | 20 | 55 | 26 | ||

| Mean R4–R6 | 3 | 18.3 | 64.3 | 28.5 | ||

| Mark | Pretest | R1 | 2 | 2 | 32 | 12 |

| R2 | 2 | 7 | 35 | 14.7 | ||

| R3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3.3 | ||

| Mean R1–R3 | 2 | 3.6 | 24.3 | 10 | ||

| Posttest | R4 | 122 | 131 | 64 | 105.7 | |

| R5 | 7 | 137 | 64 | 69.3 | ||

| R6 | 22 | 76 | 59 | 52.3 | ||

| Mean R4–R6 | 50.3 | 114.7 | 62.3 | 75.8 | ||

Note. The table shows the number of responses across the three conditions—no consequences, social consequences, and tangible consequences—for each participant. R = responses

The number of novel stimuli to which echoics were emitted did not increase systematically from baseline (Phase 3a) to after the interventions (see Table 8). Only Alan showed a greater number (19) during the final exposure to novel stimuli during the generalization BiN probe than during Baselines 1 and 2 (6 and 1, respectively) and the post-BiN probe (2). The numbers for Glen and for Mark were high and fairly constant, whereas Hans emitted slightly fewer echoics after the interventions during the post-BiN probe (6) and the generalization BiN probe (10) than during Baselines 1 and 2 (17 and 14).

Table 8.

Number of Echoic Responses During the First Part of the BiN Probes (the Exposure Phase)

| Participant | Baseline 1 | Baseline 2 | Baseline 3 | Post-BiN Probe | Generalization BiN Probe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glen | — | 18 | 19 | 15 | |

| Hans | 17 | 14 | 6 | 10 | |

| Alan | 6 | 1 | 2 | 19 | |

| Mark | 20 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

Note. The first baseline BiN probe for Glen was accidentally not videotaped for the recording of the echoic. Mark received three baseline probes

During baseline, a BiN probe to Set 1 stimuli was repeated to see if the number of correct responses changed (Phase 3b), as shown in Fig. 2. During Baseline BiN Probes 1 and 2, respectively, Hans made 6 and 1 correct listener responses, 0 and 1 tacts, and 2 and 0 manded tacts. Glen emitted 17 and 11 listener responses, 8 and 13 tacts, and 5 and 12 manded tacts. Alan made 5 and 2 listener responses, 1 and 0 tacts, and 0 and 1 manded tacts. Across Baseline BiN Probes 1 and 2, Mark’s correct listener responses increased from 1 to 4, and his number of tacts increased from 0 to 6. His number of manded tacts remained at 0. From the second to a third baseline session, the number of correct listener responses dropped from 4 to 2 and the number of tacts dropped from 6 to 4. The number of manded tacts increased from 0 in the first two probe sessions to 5 in the third (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The number of correct responses during each of the 20-trial BiN probe blocks for each participant. The white bars show the number of listener responses, the black bars show tacts, and the gray bars show manded tacts

The operants included in BiN were sequentially exposed to social conditioned reinforcers, and the participants acquired tacts in four to twelve 20-trial blocks. Hans required four, Glen twelve, Alan six, and Mark five 20-trial blocks with sequential operant instruction until the mastery criterion of 90%–100% correct responses in two subsequent trial blocks for tact responses was met (Set 2 stimuli, gemstones). The remaining BiN operants were exposed to the same number of sequential operant instruction trial blocks as the tact responses.

After the ODT procedure and the sequential operant instruction, post-BiN probes (Set 1 stimuli, pasta types) and generalization BiN probes (Set 3 stimuli, star signs) were completed. The numbers of listener responses, tacts, and manded tacts are illustrated in Fig. 2. Taken together, the number of tacts and manded tacts increased from baseline to the post-BiN probe for three of the four participants: For Alan the number increased from 1 during each of the baseline probes to 16; for Glen from 13 and 25 to 39; and for Mark from 0, 6, and 9 to 32. Mark and Glen both met the mastery criterion during the post-BiN probe. Hans and Alan did not, but Alan showed a marked increase and met the criterion during the generalization BiN probe. Only Hans never met the BiN criteria, but he made 20 correct listener responses (full score) during the final probe, the generalization BiN probe. Thus, Hans established the listener part of BiN and showed a significant improvement during tact and manded tact trials. In sum, all the participants in the present study showed improved BiN skills following sequential operant instruction after the conditioning of social stimuli as reinforcers.

Discussion

Previous research has suggested that a rotation of the different constituent operants may be necessary for the establishment of BiN (e.g., Greer et al., 2007). The question of primary interest in the present experiment was whether sequential operant instruction might also work as a successful intervention to improve BiN skills after the establishment of standard social reinforcers. All four participants had demonstrated certain prerequisites for the emission of BiN, including echoics of standard words, matching skills, listener responses, and tacts. During baseline probes, none of them demonstrated BiN nor a reinforcing effect of standard social consequences on their behavior. Following sequential operant instruction and the establishment of conditioned reinforcers, all participants showed improved BiN skills. During the generalization BiN probe, two of four participants, Alan and Mark, showed both the listener and the speaker repertoires of BiN. A third participant, Glen, met the criterion for BiN during listener and tact probes, and he made 15 of 20 correct manded tacts (75% correct responses). The lower score on manded tacts, compared to tacts, may have resulted from the fact that the tests were run in extinction and that the test of manded tacts was conducted at the very end. Glen’s decrease in on manded tacts is likely of little importance because his tacts were strong. Whenever someone performs less well on manded tacts than on tacts, it may have more to do with the motivating operation than with the stimulus control by the object. During the generalization BiN probe, Hans demonstrated only the listener part of BiN. In addition, Hans showed a significant improvement in speaker responses, as evident in the increases in the mean number of tacts from 0.75 of 20 during the baseline BiN probes to 10 of 20 tacts and manded tacts, respectively, on the generalization BiN probe.

During the post-BiN probe, Hans made few BiN operants. After the experiment, the special education teacher explained that the poor performances of BiN operants was because Hans strongly disliked pasta. However, weak BiN skills in the post-BiN and the generalization BiN probes may be a product of an insufficient conditioning procedure. Hans emitted only seven responses in the postreinforcer test. In addition, Hans’s echoic responses showed a decreasing trend during the exposure phase before post- and generalization BiN probes, which may have influenced his BiN skills during probes. Therefore, his low performance on BiN probes may have resulted from a combination of these variables.

The results of the present experiment support Longano and Greer’s (2015) proposition that conditioned reinforcers facilitate the establishment of BiN. Longano and Greer (2015) aimed to condition arbitrary novel visual and auditory stimuli as reinforcers for observing responses in order for the echoic to join listener and speaker responses and thereby improve BiN skills. As an alternative, the current study aimed to establish the natural social consequences as reinforcers for BiN skills. Before and after the conditioning of social stimuli, a reinforcer test was conducted. All participants showed an increased number of arbitrary responses during the social consequence conditions, from two to three prompted responses during the pretest to a mean of 39.9 responses during the posttest, indicating the effectiveness of the ODT procedure. This improvement was most evident for Mark. During the three social conditions (praise, nods and smiles, and acknowledgments), Mark emitted a mean of 114.7 arbitrary responses compared with only two prompted responses during the pretest. The importance of relevant social reinforcers is indicated by the fact that three of the four participants (Mark, Alan, and Glen) achieved the mastery criterion for BiN as a result of sequential operant instruction after the establishment of social reinforcers through the ODT procedure.

The present study investigated the effect of two variables on the establishment of BiN: (a) the establishment of conditioned social reinforcers and (b) sequential trials of listener and tact training. However, we assume the first variable is the most important. When a child acquires a novel tact, his or her first response is necessarily, at least partly, echoic. When that echoic is reinforced in the presence of the object, the properties of that object acquire partial control, and the tact can be observed on subsequent trials. But the object can be differentiated from other objects only if there is an appropriate history of discrimination training. Listener training requires that the child look at the object and respond discriminatively with respect to it by touching it, petting it, pushing it, tasting it, looking back and forth between it and other things, and so on. In discussions of BiN, this is a variable that is usually insufficiently addressed. “Pointing” is taken as a measure of listener behavior, but the panorama of listener behavior that children engage in when encountering an interesting object is surely much richer. MEI provides opportunities for such discrimination training in the context of tact acquisition, which may facilitate BiN. Sequential operant instruction separates them, but in principle, BiN might emerge following such a procedure because all the elements are eventually acquired. In natural environments, common objects already evoke discriminative responses, and explicit listener training should be unnecessary. It is rare that a child will not engage in a lot of untrained discriminative responses to novel animals, but it is perhaps equally rare for a child to engage in relevant discriminations to types of pasta. Unfortunately, experimental procedures of necessity usually employ novel stimuli in which the child is likely to have little interest. Therefore, failure to observe BiN may occur on motivational grounds.

However, a serious complication to this interpretation of the role of the conditioned social reinforcers is the fact that the rate of responding increased from pre- to posttest not only in the social condition but also in the tangible condition. It is possible that the general increase in response rates during the posttest results from the history of reinforced responding to prompts, rather than just from the social consequences. In addition, because the tangible reinforcers were also delivered by the researcher and, hence, involved social stimuli, the increasing response rates may also involve a habituation or desensitization to particular social stimuli. Regardless of the details of how the ODT procedure obtained its effect, it may have contributed to the effectiveness of the sequential training procedure to establish BiN skills. Furthermore, conditioned social reinforcers were the only manipulated consequences during sequential operant instruction, so tangible reinforcers could play only an indirect role in the ultimate dependent variable. Despite the fact that prerequisites were present in the participants before the present study, none of them clearly improved BiN until after the ODT procedure and sequential operant instruction. This point is central to the present study because the intervention is one of manipulating the reinforcing effectiveness of common social stimuli through the ODT procedure.

For children to learn new words for things in the environment, they must be exposed to novel names along with relevant objects, events, or actions and respond to their relevant features as SDs. During such exposures, observing responses and echoics of the novel tacts are likely. Although Longano and Greer (2015) emphasized observing responses as fundamental for the echoic to join listener and speaker responses, recent research improved BiN as a result of an SSP procedure (cf. SPOP and pairing naming) only, without explicit strengthening of any specific observing responses (e.g., Byrne et al., 2014; Carnerero & Pérez-González, 2014; Solares & Fryling, 2018). This latter finding suggests that the explicit establishment of observing responses may not be necessary.

In the present experiment, in addition to the conditioning of standard social stimuli as reinforcers, observing responses may have been strengthened by the ODT procedure. Observing responses that were seen during the ODT procedure, before presenting the SDs, were varieties of “attention-seeking” behavior, such as orienting toward the researcher, shifting the gaze toward the researcher, and making eye contact with the researcher—without instructions to do so. The ODT procedure may have fostered observing responses to SDs: For predictable access to a reinforcer in the box (which was used during all trials in the conditioning phase), participants had to respond to the presentations of social stimuli (e.g., smiles and nods) as SDs. When these stimuli were presented, the participants immediately checked the box for preferred items. According to the researchers’ anecdotal observations, the participants were increasingly more attentive to the researcher’s instructions by displaying “attention-seeking” behavior (cf. observing responses) than they were before the ODT was initiated. Thus, the results of the present experiment suggest that the ODT procedure may also enhance observing responses to the adult’s presentation of SDs more generally (cf. Donahoe & Palmer, 1994; Keohane, Delgado, & Greer, 2009). A strengthening of observing responses to clarify antecedents, before the post- and generalization BiN probes, as well as in sequential operant instruction, is a possible prerequisite that affects the acquisition of BiN skills.

Longano and Greer (2015) found a correspondence between the number of emitted echoics during the presentation of novel tacts and the number of derived BiN responses. The present experiment showed that the echoic alone is not sufficient to produce emerged BiN skills, as high numbers of echoics during baseline BiN probes were not followed by the other BiN responses. However, during the post-BiN probe and the generalization BiN probe, only those participants with the highest number of echoics (Glen, Alan, and Mark) scored within the criterion for derived BiN responses. In contrast to Longano and Greer (2015), Byrne et al. (2014) did not find a correspondence between emerged listener responses and tacts and echoics emitted during SPOP and listener tests. But the acquisition of tacts necessarily entails echoic behavior—unless the tact is shaped through successive approximations (e.g., such as that often implemented with deaf children). When a correctly enunciated tact is acquired by a child in a trial or two, the echoic repertoire is implied. The fact that modeling alone is insufficient is easily shown by presenting a word in a language in which the child has no echoic repertoire. Consequently, we can confidently assume that the echoic plays a role in all “naming,” in at least the technical sense of whether it is measured or not. Whether the child echoes a novel word or not can be a matter of motivation, and that is a variable that is often omitted in discussions of BiN. However, echoic behavior may occur covertly, as suggested by Horne and Lowe (1996), but that would place the question about the correspondence between echoic and emerged BiN responses beyond the reach of the current study.

A limitation of the present experiment is the omission of BiN probes after the conditioning of social reinforcers and before the implementation of sequential operant instruction. Future research should include BiN probes after the conditioning procedure to isolate the effect of the ODT procedure from the product of the sequential operant instruction on BiN.

A second possible weakness is the use of a pre- and posttest design instead of a multiple-baseline design across participants (Carr, 2005). We replicated the design most commonly used by Greer et al., who have conducted a substantial number of studies on the emergence of BiN. However, the present study included repeated baseline BiN probes and replications across four participants in four different day care centers, which may have strengthened experimental control (Petursdottir & Carr, 2018). It is implausible that all four participants’ programs, by chance, introduced relevant training that coincided with the phases of the experiment, and it is equally implausible that all four children passed a relevant but unspecified “developmental milestone” at the same time. Further, the repetition of baseline BiN probes until a stable trend was achieved was crucial. The experimental procedures actually implemented an unsystematic multiple-baseline procedure, or at least a nonconcurrent multiple-baseline design. That is, the baseline phases were extended until behavior “reached stability,” which suggests that these phases were of different lengths across participants. For instance, Mark received three baseline BiN probes without any significant change in BiN skills. Thus, continued improvement in BiN skills caused by repeated probing was unlikely. There is a possible exception in Glen’s case: Responses during the second baseline probe had increased somewhat from the first. Thus, in the case of Glen, a separate effect of repeated testing cannot be excluded. For the remaining participants, improved BiN skills could be ascribed to the conditioning procedure and the subsequent intervention rather than to the repeated probing only.

The present experiment extends previous research on variables that influence BiN by showing that explicit MEI, or the rotation of BiN operants, may not be necessary for the establishment of BiN. Despite limitations, a reasonable interpretation of the present experiment is that both ODT and sequential operant instruction were active components of the intervention. If so, it is possible that a core characteristic of a history that produces BiN repertoires is to change the function of stimuli presented in BiN probes into SDs, which signal reinforcement for accurate tacting and listener behavior. That is, in addition to establishing naming as a “skill” or “joined repertoires,” effective interventions may also have to establish “a good reason to respond” (i.e., effective reinforcement) in the natural environment.

The acquisition of BiN is fundamental because these skills can improve the educational prognosis (Gilic & Greer, 2011) and accelerate the rate of learning through exposure to others’ demonstrations (Choi, Greer, & Keohane, 2015; Greer, Corwin, & Buttigieg, 2011; Greer, Pistoljevic, Cahill, & Du, 2011; Hranchuk, Greer, & Longano, 2018). It may turn out that a priority in future work with children with autism will be the establishment of standard social consequences as reinforcers as early on as possible because social behaviors, such as BiN, are necessarily maintained by such consequences in the natural environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Cecilie Belinda Jørgensen for assistance with data collection. We also would like to thank Danielle LaFrance for the generosity of her time in making revisions and helpful comments on a previous version of this article.

Funding

The experiment was funded by Oslo Metropolitan University, Faculty of Health, Institute for Behavioral Sciences.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

In advance, the Norwegian Center for Research Data approved the present experiment.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants’ caregivers, as well as from the managers of the day care centers that the participants attended.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Baldwin DA. Infants’ contribution to the achievement of joint reference. Child Development. 1991;62:875–890. doi: 10.2307/1131140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict H. Early lexical development: Comprehension and production. Journal of Child Language. 1979;6:183–200. doi: 10.1017/S0305000900002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BL, Rehfeldt RA, Aguirre AA. Evaluating the effectiveness of the stimulus pairing observation procedure and multiple exemplar instruction on tact and listener responses in children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:160–169. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y., & Greer, R. D. (2019). Mastery of echoics in Chinese establishes bidirectional naming in Chinese for preschoolers with naming in English. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40616-018-0106-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carnerero JJ, Pérez-González LA. Induction of naming after observing visual stimuli and their names in children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35:2514–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr J. Recommendations for reporting multiple-baseline designs across participants. Behavioral Interventions. 2005;20:219–224. doi: 10.1002/bin.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Learning. Cornwall-on-Hudson, NY: Sloan Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Greer RD, Keohane D-D. The effects of an auditory match-to-sample procedure on listener literacy and echoic responses. Behavioral Development Bulletin. 2015;20:186–206. doi: 10.1037/h0101313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon, I. G., & Iwata, B. A. (1996). Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29, 519–533. 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Donahoe JW, Palmer DC. Learning and complex behavior. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eikeseth S, Smith D, Klintwall L. Discrete trial teaching and discrimination training. In: Sturmey P, Tarbox J, Dixon D, Matson JL, editors. Handbook of early intervention for autism spectrum disorders: Research, practice, and policy. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 229–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorile, C. A., & Greer, R. D. (2007). The induction of naming in children with no prior tact responses as a function of multiple exemplar histories of instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 23, 71–87. 10.1007/bf03393048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gale, C. M., Eikeseth, S., & Klintwall, L. (2019). Children with autism show atypical preference for non-social stimuli. Scientific Reports, 9, article no. 10355. 10.1038/s41598-019-46705-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ghezzi PM. Discrete trials teaching. Psychology in the Schools. 2007;44:667–679. doi: 10.1002/pits.20256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilic, L., & Greer, R. D. (2011). Establishing naming in typically developing two-year-old children as a function of multiple exemplar speaker and listener experiences. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 157–177. 10.1007/bf03393099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greer, R. D., Corwin, A., & Buttigieg, S. (2011). The effects of the verbal developmental capability of naming on how children can be taught. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 1, 23–54. 10.22201/fpsi.20074719e.2011.1.214

- Greer RD, Du L. Generic instruction versus intensive tact instruction and the emission of spontaneous speech. The Journal of Speech and Language Pathology— Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;5:1–19. doi: 10.1037/h0100261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Du L. Experience and the onset of the capability to learn names incidentally by exclusion. The Psychological Record. 2015;65:355–373. doi: 10.1007/s40732-014-0111-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Du L. Identification and establishment of reinforcers that make the development of complex social language possible. International Journal of Behavior Analysis & Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;1:13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, R. D., & Longano, J. M. (2010). A rose by naming: How we may learn how to do it. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 26, 73–106. 10.1007/bf03393085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greer, R. D., Pistoljevic, N., Cahill, C., & Du, L. (2011). Effects of conditioning voices as reinforcers for listener responses on rate of learning, awareness, and preferences for listening to stories in preschoolers with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 103–124. 10.1007/bf03393095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greer RD, Pohl P, Du L, Moschella JL. The separate development of children’s listener and speaker behavior and the intercept as behavioral metamorphosis. Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science. 2017;7:674–704. doi: 10.4236/jbbs.2017.713045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Ross DE. Verbal behavior analysis: Inducing and expanding new verbal capabilities in children with language delays. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, R. D., Stolfi, L., Chavez-Brown, M., & Rivera-Valdes, C. (2005). The emergence of the listener to speaker component of naming in children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 21, 123–134. 10.1007/bf03393014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greer RD, Stolfi L, Pistoljevic N. Emergence of naming in preschoolers: A comparison of multiple and single exemplar instruction. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2007;8:109–131. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2007.11434278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, E., Kingsdorf, S., Charnock, J., Szabo, M., & Gautreaux, G. (2009). Effects of multiple exemplar instruction on naming. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 10, 265–273. 10.1080/15021149.2009.11434324

- Holth P. An operant analysis of joint attention. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention. 2005;2:160–176. doi: 10.1037/h0100311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]