Abstract

Metastasis is a major risk for lung adenocarcinoma-related mortality. Accumulating evidence raises the possibility that anticancer therapies might be more sensitive by targeting premetastatic niches in addition to the cancer cells themselves. Here, we identified a subpopulation of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, which was characterized by EMT-related markers such as E-cadherin, Twist, SMAD, and β-catenin. EMT+ cases exhibited poorer prognosis than EMT- patients, reflecting the pro-metastatic features of EMT. Immunohistochemical staining decorated CD15+ PMN-MDSCs surrounding EMT+ cancer cells in lymph nodes. Metastatic tissues secreted high levels of chemokines, including CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL2, into the circulation to recruit histidine decarboxylase (Hdc)-positive PMN-MDSCs into metastatic colonies through upregulated CXCR2. The percentage of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs increased in the setting of metastasis. Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs obtained from EMT+ metastatic masses expressed a higher level of TGF-β1, rather than TGF-β2 and TGF-β3, compared to EMT- counterparts. The depletion of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs or downregulation of TGF-β1 significantly decreased EMT+ percentage and, thus, hampered the metastasis process in murine models. Together, our findings suggest that metastatic tumor secretes high levels of chemokines to recruit Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs, which, in turn, express TGF-β1 to induce cancer cells to undergo EMT at metastatic sites.

Keywords: MDSCs, lung adenocarcinoma, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, TGF-β, metastasis

Introduction

Despite rapid advances in clinical diagnosis and treatments, lung cancer remains the first leading cause of cancer-related death [1]. Basing on histologic features, lung cancer can be subdivided into four most common types: small cell lung carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma (LAC), squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma. The prognosis of LAC is dependent on the tumor stage at the time of diagnosis. A major reason for cancer-related mortality is the metastasis after surgery or ablation therapy, because the cascade may occur before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Progress in the fight against LAC has been substantial over the last decade with the discovery of immunotherapies. However, further studies have been hampered by the complex interactions between tumor cells and the elements of tumor-associated microenvironment (TAM). During the sequential neoplastic progression from non-resolving inflammation to metastasis, biologic behaviors and phenotypes of tumor cells can change in response to stress such as immune surveillance, apoptosis, and physical destruction in the circulation.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a conserved biological event identified in embryogenesis, mediates tumor progression, including invasion through the surrounding mesenchymal tissue, surviving in the circulation, and metastasis. The proteomic features of epithelial cells undergoing EMT include the loss of epithelial marker E-cadherin, β-catenin translocation, and the acquisition of fibroblast and nuclear factors, including S100A4, Twist, and SMAD [2]. These changes endow tumor cells with an elongated shape and enhanced motility resembling cells of mesenchymal origin. Several EMT markers are proposed as independent predictors for patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma [3]. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), appreciated as one of the most powerful drivers of EMT, can synergize with JAK/STAT3 pathway and contribute to cancer cell migration and invasion [4]. The activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) attenuated TGF-β-induced EMT and metastasis by antagonizing Smad3, which forms a trimeric structure with Smad4 and translocates to the nucleus to regulate the expression of downstream genes [5,6].

However, the roles of EMT in the metastatic progression are still a matter of debate. One of the most concerning issues is the exact cellular source of TGF-β1. The presence of high levels of TGF-β1 has been demonstrated in many tumors [7]. Several types of cells, including cancer-associated myofibroblast, cancer cells, and platelet, are proposed as attractive candidates [8]. Immune cells, widely appreciated as one of the most important regulators of microenvironment, play a central role during LAC tumorigenesis and progression. Malignant cells can promote the recruitment and expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) through the secretion of chemokines, including GM-CSF, IFNγ, and Cox-2 [9-11]. The depletion of infiltrating MDSCs hampered the progression of lung cancer [12].

MDSCs are heterogenous and can be subdivided into two types: the granulocytic MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs, CD45+CD11b+Ly6Ghi) and monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs, CD45+CD11b+Ly6Chi) [13]. Our recent study suggested that histidine decarboxylase (Hdc) marked a distinct subpopulation of myeloid-biased hematopoietic stem cells/progenitor cells (MB-HSC/HSPC), which could be the cellular source of tumor-associated immature myeloid cells in the context of aging or tumor [14]. Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs are central to the tumorigenesis of colon cancer [15,16]. Yet we have little definitive information about whether Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs contributes to the metastasis of lung cancer.

In this study, we compared the prognosis of EMT+ metastatic LAC cases to that of EMT-negative counterparts and found that EMT may serve as a predictive marker. Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs were recruited into metastatic masses of transgenic murine models. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the closely spatial relationship between Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs and EMT+ metastatic cancer cells, raising the possibility that Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived factors may influence the behaviors of EMT+ cells by a paracrine pattern. Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs expressed high levels of TGF-β1 rather than TGF-β2 and TGF-β3. The depletion of Hdc+ cells or the block of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 resulted in the inhibition of metastasis. Our preliminary data further reveal the important role of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs in the metastatic cascade of LAC, suggesting a promising target for anti-LAC strategies.

Materials and methods

Patients and clinical data

This study included 122 LAC patients with accurate pathologic diagnosis of metastasis. Achieves were collected and evaluated. All patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and this study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of The Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University.

Mouse models

All animal experiment protocols were approved by Nanchang University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Hdc-CreERT2; eGFP mice were purchased from EMMA. LSL-Kras G12D, Lkb1L/-, Tgf-βL/-, and iDTR mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. To establish metastatic LAC models, LSL-Kras G12D mice were crossed to Lkb1L/- followed by the administration with high doses (5 × 108 PFU) of AdenoCre by intranasal instillation at 6 weeks of age as previously described [17]. To trace biologic roles of Hdc+ myeloid cells in the metastatic stages, we crossed Hdc-CreERT2; eGFP; iDTR to LSL-Kras G12D; Lkb1L/- mice. These models were treated with the combination of AdenoCre and diphtheria toxin (DT, sigma) to abolish effects of Hdc+ myeloid cells. We generated Hdc-CreERT2; eGFP; LSL-Kras G12D; Lkb1L/-; Tgf-βL/- mice to pinpoint the exact molecular pathway by which Hdc+ myeloid cells regulate biologic behaviors of metastatic LAC cells. We further established Hdc-CreERT2; eGFP; LSL-Kras G12D; Lkb1L/-; Tgf-βL/-; iDTR mouse models and compared changes of EMT and tumor progression among different groups. All mice were backcrossed and maintained at C57BL/6 background and housed in the special pathogen-free animal facilities.

Histopathologic evaluation

Formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded blocks were arrayed by the tissue arrayer TMAjr (Pathology Devices). Serial sections were cut in 3- to 4-μm slides followed by H&E and immunohistochemical staining. The histopathologic evaluation of all sections was performed by two independent pathologists (L Zhou and J Hu), who were blinded regarding details. Primary antibodies for Twist (1:100; ab49254, Abcam), SMAD3 (1:100; clone EP568Y, Abcam), CD15 (1:150; clone Carb-1, Novocastra, Leica), E-cadherin (1:200; clone M168, Abcam), and β-catenin (1:200; ab32572, Abcam) were used in the slide stainer (Autostainer 360, Lab Vision, Thermo Fisher). A microscope (80i, Nikon) with the CCD camera (DS-Ri2, Nikon) was used to perform the image analysis. Counting of positive cells was conducted in non-overlapping fields using the 40 × objective. The average number of positive cells in each square centimeter was calculated for each specimen.

Flow cytometry analysis

Fresh tissues obtained from lung or lymph node were manually minced and incubated in DMEM with Collagenase A (Roche) and DNAse I (Roche) for 45 min at 37°C. Suspensions were filtered three times using a 70 μm nylon mesh to remove dead cell debris and enrich leucocytes. No more than 1 × 106 cells were incubated with the antibody panel composed of CD45 (30-F11, eBioscience), CD11b (M1/70, eBioscience), and Ly6G (1A8, eBioscience). PMN-MDSCs were identified based on their phenotype: CD45+CD11b+Ly6Ghi. Hdc+ cells were characterized by their high level of GFP expression (GFPhi). CD45+CD11b+Ly6GhiGFPlo cells harvested from eGFP wild type littermates were used to set the gate. Stained cells were fixed with Cytofix (BD Bioscience) for 30 min on ice and analyzed by LSR II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience).

RNA-seq analysis

Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs were sorted and lysed in ARCTURUS PicoPure RNA isolation kit according to manufacturer’s instruction (Life Technologies). Total RNA was isolated followed by cDNA amplification. Libraries were established using SMARTer Ultra Low Input RNA kit (Clontech Laboratories) and Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina). Sequencing was performed on Hiseq 2500 (Illumina).

Gene microarray analysis

Both Hdc+ and Hdc- PMN-MDSCs were harvested from EMT+ and EMT- metastatic lesions. Total mRNA was extracted using Rneasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and labeled by 3’ IVT Expression Kit (Affymetrix) before hybridized to the Affymetrix GeneChip mouse genome 430 2.0 array (Affymetrix). Arrays were performed using an Affymetrix Scanner 300-7G scanner with GCOS software. A significance cut-off of a Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate ≤ 0.05 was been applied.

Chemokine analysis and quantitative RT-PCR

Sera obtained from both MET+ and EMT- metastatic LAC mice were detected by LEGENDplex Mouse Proinflammatory Panel (Biolegend) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Total mRNA of sorted cells was isolated using Rneasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) and underwent reverse transcription using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies). PrimerQuest Tool (Intetrated DNA Technologies) was used to design sequences of SYBR Green for CXCR2, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 (Table 1). Quantitative PCR was performed with the StepOne Plus machine (Applied Biosystems Prism). Relative gene expression was normalized to GAPDH.

Table 1.

Primers for quantitative RT-PCR

| Gene Symbol | Organism | Gene Name | Forward Primer (5’-3’) | Reverse Primer (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1 | Mus musculus | transforming growth factor, beta 1 | CCAGATCCTGTCCAAACTAAGG | CTTCCCGAATGTCTGACGTATT |

| TGF-β2 | Mus musculus | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | GAGTGGCTTCACCACAAAGA | TGTAGGAGGGCAACAACATTAG |

| TGF-β3 | Mus musculus | transforming growth factor, beta 3 | CGCTACATAGGTGGCAAGAA | CTGGGTTCAGGGTGTTGTATAG |

| CXCR2 | Mus musculus | chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 2 | CCAGTTAGGGATGATGGGAAAG | CTGGGTTTGGTGGTTGTTTATG |

| CCR2 | Mus musculus | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 | GAGCACTAGACTTCAGACTA | TGACTAGGCTAGCCTGGCAGCT |

| GAPDH | Mus musculus | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | CTTTGTCAAGCTCATTTCCTGG | TCTTGCTCAGTGTCCTTGC |

Statistical analysis

Experimental results were replicated at least once, unless otherwise indicated. Sample sizes for each study were estimated on the basis of the expected differences and previous experience with the particular assay. All data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Kaplan-Meier survival was statistically analyzed by Log-rank test. Other statistical comparisons were evaluated with Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA. Significance levels were set at *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant. N indicates biological replicates. Data analyses were carried out using Prism 8 (Graphpad).

Results

EMT promoted LAC progression

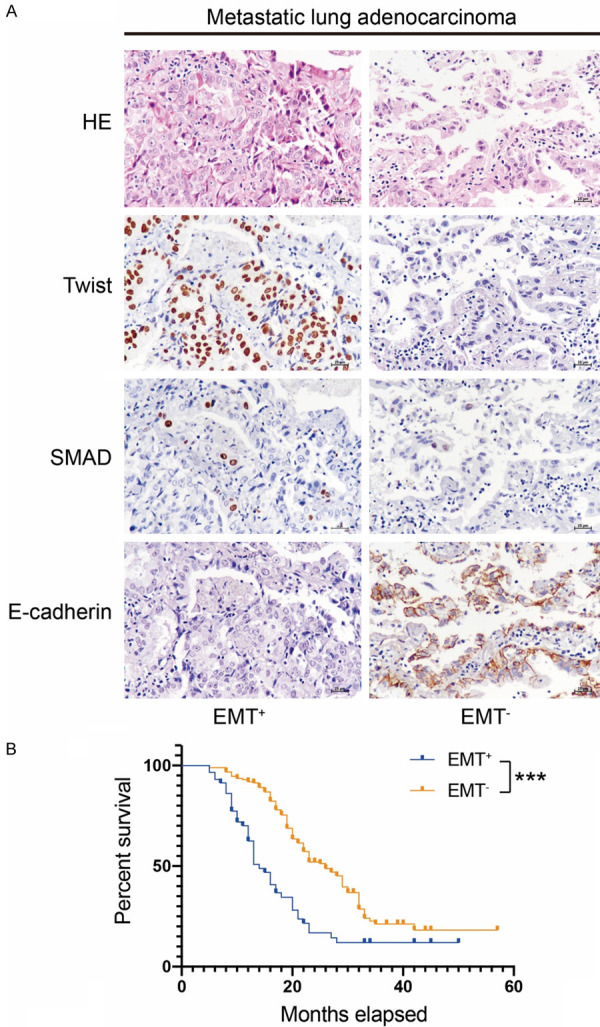

There has been substantial progress in our understanding of the contribution of EMT to lung cancer carcinogenesis. However, the possibility that EMT-related markers serve as predictors for prognosis remains a subject of intense investigations. Among 244 LAC cases, EMT+ cancer cells (Twist+SMAD3+E-cadherin-) in metastatic lesions were observed in 58 cases (23.8%) (Figure 1A). The retrospective analysis suggested that the EMT+ metastatic LAC patients had a shorter survival time than EMT- counterparts (P < 0.001) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Expression of EMT-related markers in metastatic lung adenocarcinoma (LAC). (A) A portion of metastatic LAC showed nuclear immunopositivity for EMT-related marker Twist and SMAD. E-cadherin negativity served as an initial event of EMT. (B) Patients with EMT+ metastatic LAC possessed a poorer prognosis compared to that of EMT- cases (P < 0.001). Original magnification × 400 (A).

MDSCs infiltrated EMT+ metastatic lesions

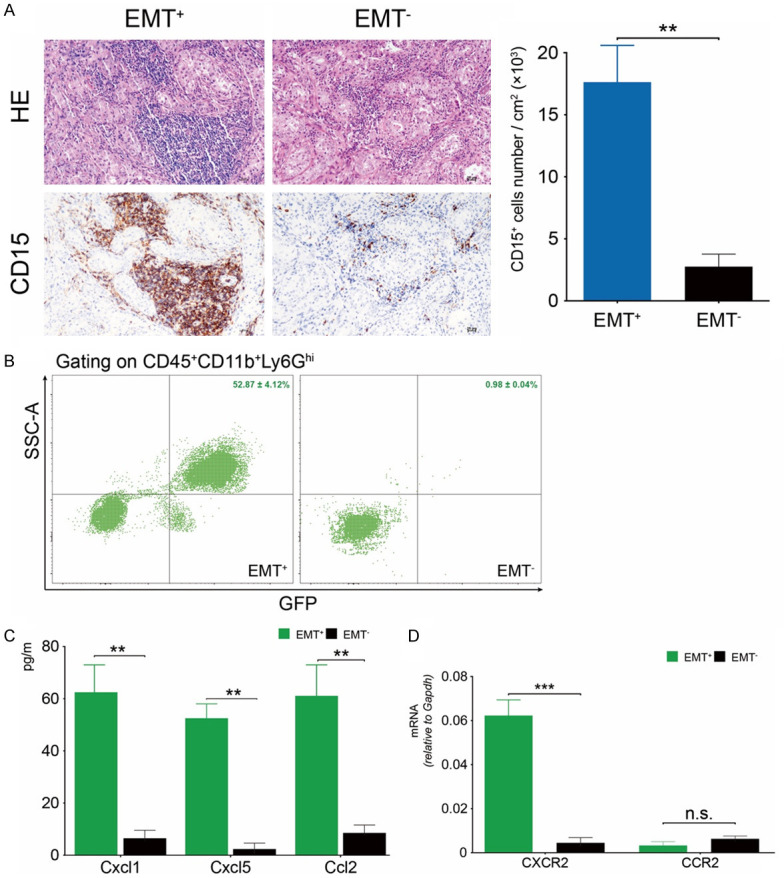

MDSCs are a heterogeneous entity recruited from the bone marrow to the microenvironment and promote neoplastic progression. Consistent with previous studies, CD15+ PMN-MDSCs exhibited a propensity towards EMT+ lymph node masses, rather than EMT- tumors (Figure 2A) [18]. The quantification data confirmed the immunohistochemical results (Figure 2A). One of our previous studies indicated that Hdc can mark a distinct population of MB-HSC/HSPCs, which may serve as the cellular source of tumor-related immature myeloid cells [14,15]. FACS analysis showed an increased percentage of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs in EMT+ metastatic lesions (52.87 ± 1.3%) rather than in EMT+ counterparts (0.98 ± 0.04%) (P < 0.001) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

PMN-MDSCs infiltrated EMT+ metastatic lesions. (A) CD15+ PMN-MDSCs were recruited into metastatic masses and showed close spatial relationships with cancer cells. The number of CD15+ PMN-MDSCs increased in EMT+ rather than EMT- tumors (P < 0.01). (B) FACS results confirmed an increased percentage of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs in EMT+ colonies (P < 0.001). (C) Levels of serum CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL2 in EMT+ models were higher than that of EMT- mice (P < 0.01). (D) Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs obtained from EMT+ tissues expressed a higher level of CXCR2, rather than CCR2, compared to counterparts isolated from EMT- tumors (P < 0.001). Original magnification × 400 (A).

Cancer tissues can secrete high levels of chemokines into the circulatory system to recruit PMN-MDSCs [19]. The results of proinflammatory chemokines panel test showed that serum levels of CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL2 in EMT+ metastatic group were higher than that of EMT- mice (Figure 2C). CXCL1 and CXCL5 can bind to CXCR2 receptor to recruit granulocytic cells. CCL2/CCR2 axis contributes to monocyte trafficking [20]. Real-time PCR showed that CXCR2, rather than CCR2, was upregulated in Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs obtained from EMT+ metastatic tissues (Figure 2D).

Hdc+ cell-derived TGF-β1 and EMT of metastatic lesions

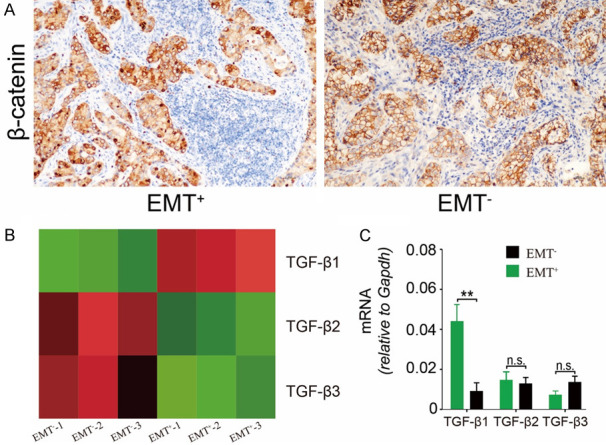

The β-catenin pathway plays a key role in the induction of EMT. The upregulated expression of Twist can activate β-catenin and AKT to promote morphologic and phenotypic changes of cancer cells through the EMT process [21]. The immunohistochemical staining demonstrated the aberrant cytoplasmic and nuclear immunopositivity for β-catenin in metastatic malignant cells (Figure 3A). TGF-β, one canonical driver for EMT, is always upregulated in microenvironment. However, the exact cellular source is still unknown. RNA-seq analysis data revealed that Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs obtained from EMT+ metastatic masses expressed higher levels of TGF-β1, but not TGF-β2 and TGF-β3, compared to EMT- counterparts (Figure 3B). These results were further confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 3C), suggesting the involvement of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 in the advanced stages of LAC.

Figure 3.

Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs secreted TGF-β1 to promote EMT. (A) Aberrant translocation of β-catenin from the membrane to the cytoplasm and nucleus was observed in EMT+ metastatic cells. (B) RNA-seq results demonstrated that TGF-β1, rather than TGF-β2 and β3, was upregulated in Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs cells obtained from EMT+ metastatic tumors. (C) qRT-PCR further confirmed high levels of Hdc+ cells-derived TGF-β1 (P < 0.01). Original magnification × 200 (A).

Blocking of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 hampered metastasis

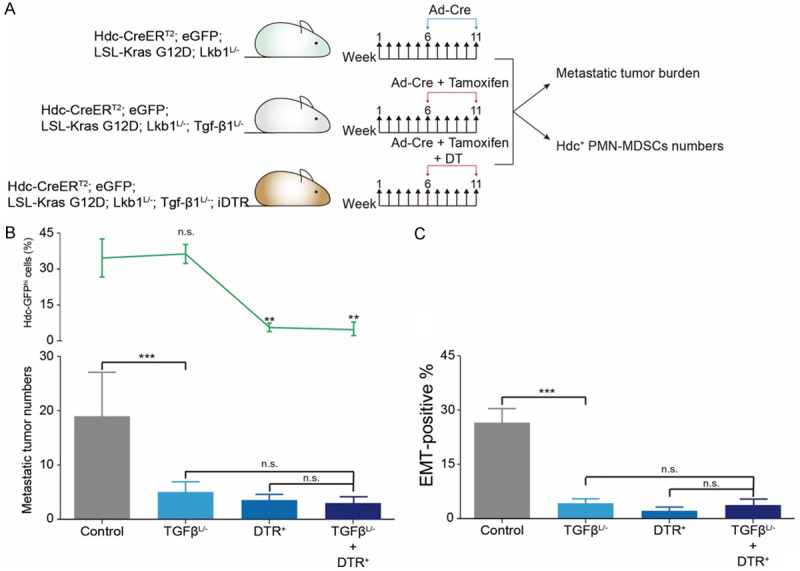

We proposed the possibility that Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 serves as a key risk factor for LAC metastasis. Thus, the Hdc-CreERT2; eGFP; LSL-Kras G12D; Lkb1L/- mice were crossed to Tgf-β1L/- and iDTR mice respectively to eliminate the effects of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1. FACS results indicated that the downregulation of TGF-β1 did not influence the percentage of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs (P > 0.05) (Figure 4B). However, the number of metastatic lesions decreased significantly in both Tgf-β1L/- (5.1 ± 0.3) and iDTR mice (3.8 ± 0.2) compared to that of Hdc-CreERT2; eGFP; LSL-Kras G12D; Lkb1L/- mice (18.2 ± 1.1) (Figure 4B). However, the combination of TGF-β1 downregulation and Hdc+ ablation did not further inhibit the metastasis of LAC (Figure 4B). Consistent with tumor burden, the percentage of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs decreased significantly in iDTR groups rather than control and Tgf-β1L/- groups (Figure 4B). The EMT+ rates in metastatic individuals exhibited the same tendency, reflecting the central role of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 in the metastatic cascade (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 promoted EMT and metastasis. A. Amoxifen chow induced the downregulation of Hdc+ cells-derived TGF-β1 in Tgf-βL/- mice. Hdc+ cells were deleted by DT. B. A block of Hdc+ cells or Hdc+ cells-derived TGF-β1 decreased the number of metastatic tumors (p < 0.001). The distinction of anti-metastasis abilities between Tgf-βL/-, iDTR, and Tgf-βL/- + iDTR groups was not significant. C. EMT+ percentage decreased in Tgf-βL/-, iDTR, and Tgf-βL/- + iDTR animals (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Reducing metastasis has been the focus of recent anti-cancer strategies. Establishment of secondary colonies at distant sites is the rate-limiting step. Here we have identified a subpopulation of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma (LAC), which was characterized by EMT-related markers and possessed a poorer prognosis compared to EMT- cases. EMT+ metastatic tissues secreted high levels of CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL2 to recruit Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs through the upregulated CXCR2. Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs expressed an increased level of TGF-β1 to induce the translocation of β-catenin from the membrane to the cytoplasm and nucleus. The downregulation of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 decreased the EMT+ percentage in secondary colonies and attenuated the metastatic ability of LAC.

Although several clinical and genetic risk factors have been proposed, few have been demonstrated to be relevant in predicting the prognosis of patients with metastatic lesions. Malignant cells can detach from primary sites and enter lymph node or hematogenous system before onset of obvious symptoms. The successful establishment of secondary colonies at distant sites is crucial for disseminated tumor cells. They have adapted to cope well with host surveillance and insults through phenotypic and functional changes typical of EMT [22]. However, a substantial study indicated that EMT status at primary lung cancer sites did not influence the prognosis [23]. Our retrospective data indicated that EMT-related markers pinpointed a distinct subpopulation, which exhibited poorer prognosis than that of EMT- counterparts. These preliminary data supported the hypothesis that EMT endows disseminated cells with enhanced migratory, invasive and anti-apoptosis abilities [24,25].

After leaving the supportive primary sites, disseminated cells will face severe survival challenges. Malignant cells can induce the formation of pre-metastatic niches in distant lymph nodes or organs before landing on these sites [26]. MDSCs, a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells exposing immunosuppressive effects at pre-metastatic niches, have been linked to extra-thoracic metastasis and poor response to anti-cancer treatments in patients with lung cancer [27]. Accumulating evidence suggests that PMN-MDSCs are recruited mainly through CXCLs, including CXCL1, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL12 [28]. Of note is the fact that CCL2, an important factor in M-MDSCs recruitment, also can drive PMN-MDSCs trafficking to primary tumors [29]. Malignant tumor tissues also can influence MDSCs recruitment indirectly through the upregulated level of tumor-associated macrophages-derived CXCL1, which, in turn, recruits CXCR2-expressing MDSCs to form a pre-metastatic niche [30]. High levels of CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL2 in distant sites were consistent with previous observations. However, CXCL1/CXCL5 receptor CXCR2, rather than CCL2 receptor CCR2, was upregulated in Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs, indicating the possibility that activated pathways may vary depending on the progression of cancer.

TGF-β1 is increasingly recognized as a key regulator of normal cell events. However, cancer cells can take advantage of TGF-β1 features to escape the host surveillance. Cancer-related EMT can be driven by microenvironmental TGF-β1. Recruited MDSCs secreted membrane bound TGF-β1 to inhibit the cytotoxicity of NK cells, which are involved in the first line of the anti-cancer battle [31]. A recent study further pinpointed the exact identity of these immune cells is PMN-MDSCs [32]. Substantial evidence showed that TGF-β1 on MDSCs was critical for the EMT cascade of primary tumors [33]. In this study, infiltrated Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs in metastatic tumor showed a closely spatial relationship with EMT+ cells, raising the possibility that Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived factors may regulate biologic behaviors of targeted cells through a paracrine pattern. The upregulated level of TGF-β1, rather than TGF-β2 and TGF-β3, in Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs was consistent with previous studies and indicated the involvement of TGF-β1-dependent EMT. The ablation of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs or Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs-derived TGF-β1 through transgenic mice decreased both metastatic tumor burden and EMT+ percentage, further supporting the hypothesis that Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs can secrete TGF-β1 to promote cancer cells undergoing EMT at metastatic sites.

In summary, we identified and characterized EMT+ metastatic LAC, exhibiting nuclear positivity for Twist, SMAD3, and β-catenin, as a distinct subpopulation with a poorer prognosis compared to that of EMT- cases. The metastatic cells in lymph node expressed high levels of chemokines, including CXCL2, CXCL5, and CCL2, to recruit Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs through enhanced CXCR2. Infiltrated Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs secreted TGF-β1 to induce malignant cells undergoing EMT via a paracrine pattern. The ablation of Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs or downregulation of TGF-β1 in vivo decreased the tumor burden and EMT+ rates of metastatic individuals. Given the more accurate definition of MDSCs subpopulation and pro-EMT ability, the tailored immunotherapies based on targeting Hdc+ PMN-MDSCs might be of therapeutic benefit.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81770624, 81860490), the Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province for Distinguished Young Scholars, China (20192BCB23025), and Foundation of Health and Family Planning Commission of Jiangxi Province (20171098) to H.D.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang W, Pang XG, Wang Q, Shen YX, Chen XK, Xi JJ. Prognostic role of Twist, Slug, and Foxc2 expression in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer after curative resection. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu RY, Zeng Y, Lei Z, Wang L, Yang H, Liu Z, Zhao J, Zhang HT. JAK/STAT3 signaling is required for TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:1643–1651. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reka AK, Kurapati H, Narala VR, Bommer G, Chen J, Standiford TJ, Keshamouni VG. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation inhibits tumor metastasis by antagonizing Smad3-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3221–3232. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill CS. Transcriptional control by the SMADs. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8:a022079. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie W, Mertens JC, Reiss DJ, Rimm DL, Camp RL, Haffty BG, Reiss M. Alterations of Smad signaling in human breast carcinoma are associated with poor outcome: a tissue microarray study. Cancer Res. 2002;62:497–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massague J. TGFbeta in cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallina G, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, De Santo C, Marigo I, Colombo MP, Basso G, Brombacher F, Borrello I, Zanovello P, Bicciato S, Bronte V. Tumors induce a subset of inflammatory monocytes with immunosuppressive activity on CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2777–2790. doi: 10.1172/JCI28828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha P, Clements VK, Fulton AM, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Prostaglandin E2 promotes tumor progression by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4507–4513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, Tan G, Bronte V, Borrello I. High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6337–6343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shvedova AA, Tkach AV, Kisin ER, Khaliullin T, Stanley S, Gutkin DW, Star A, Chen Y, Shurin GV, Kagan VE, Shurin MR. Carbon nanotubes enhance metastatic growth of lung carcinoma via up-regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Small. 2013;9:1691–1695. doi: 10.1002/smll.201201470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Pittet MJ. The role of myeloid cells in cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:447–462. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Deng H, Churchill MJ, Luchsinger LL, Du X, Chu TH, Friedman RA, Middelhoff M, Ding H, Tailor YH, Wang ALE, Liu H, Niu Z, Wang H, Jiang Z, Renders S, Ho SH, Shah SV, Tishchenko P, Chang W, Swayne TC, Munteanu L, Califano A, Takahashi R, Nagar KK, Renz BW, Worthley DL, Westphalen CB, Hayakawa Y, Asfaha S, Borot F, Lin CS, Snoeck HW, Mukherjee S, Wang TC. Bone marrow myeloid cells regulate myeloid-biased hematopoietic stem cells via a histamine-dependent feedback loop. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:747–760. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Takemoto Y, Deng H, Middelhoff M, Friedman RA, Chu TH, Churchill MJ, Ma Y, Nagar KK, Tailor YH, Mukherjee S, Wang TC. Histidine decarboxylase (HDC)-expressing granulocytic myeloid cells induce and recruit Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in murine colon cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1290034. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1290034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang XD, Ai W, Asfaha S, Bhagat G, Friedman RA, Jin G, Park H, Shykind B, Diacovo TG, Falus A, Wang TC. Histamine deficiency promotes inflammation-associated carcinogenesis through reduced myeloid maturation and accumulation of CD11b+Ly6G+ immature myeloid cells. Nat Med. 2011;17:87–95. doi: 10.1038/nm.2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Montoya R, Jacks T, Tuveson DA. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott LA, Doherty GA, Sheahan K, Ryan EJ. Human tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells: phenotypic and functional diversity. Front Immunol. 2017;8:86. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar V, Donthireddy L, Marvel D, Condamine T, Wang F, Lavilla-Alonso S, Hashimoto A, Vonteddu P, Behera R, Goins MA, Mulligan C, Nam B, Hockstein N, Denstman F, Shakamuri S, Speicher DW, Weeraratna AT, Chao T, Vonderheide RH, Languino LR, Ordentlich P, Liu Q, Xu X, Lo A, Pure E, Zhang C, Loboda A, Sepulveda MA, Snyder LA, Gabrilovich DI. Cancer-associated fibroblasts neutralize the anti-tumor effect of CSF1 receptor blockade by inducing PMN-MDSC infiltration of tumors. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:654–668. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palomino DC, Marti LC. Chemokines and immunity. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015;13:469–473. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082015RB3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Zhou BP. Activation of beta-catenin and Akt pathways by Twist are critical for the maintenance of EMT associated cancer stem cell-like characters. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng H, Wang HF, Gao YB, Jin XL, Xiao JC. Hepatic progenitor cell represents a transitioning cell population between liver epithelium and stroma. Med Hypotheses. 2011;76:809–812. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chikaishi Y, Uramoto H, Tanaka F. The EMT status in the primary tumor does not predict postoperative recurrence or disease-free survival in lung adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:4451–4456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lou XL, Sun J, Gong SQ, Yu XF, Gong R, Deng H. Interaction between circulating cancer cells and platelets: clinical implication. Chin J Cancer Res. 2015;27:450–460. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2015.04.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peinado H, Zhang H, Matei IR, Costa-Silva B, Hoshino A, Rodrigues G, Psaila B, Kaplan RN, Bromberg JF, Kang Y, Bissell MJ, Cox TR, Giaccia AJ, Erler JT, Hiratsuka S, Ghajar CM, Lyden D. Pre-metastatic niches: organ-specific homes for metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:302–317. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang A, Zhang B, Wang B, Zhang F, Fan KX, Guo YJ. Increased CD14(+)HLA-DR (-/low) myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with extrathoracic metastasis and poor response to chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:1439–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1450-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI. The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chun E, Lavoie S, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Kim J, Soucy G, Odze R, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. CCL2 promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by enhancing polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cell population and function. Cell Rep. 2015;12:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang D, Sun H, Wei J, Cen B, DuBois RN. CXCL1 is critical for premetastatic niche formation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3655–3665. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Han Y, Guo Q, Zhang M, Cao X. Cancer-expanded myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce anergy of NK cells through membrane-bound TGF-beta 1. J Immunol. 2009;182:240–249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sceneay J, Chow MT, Chen A, Halse HM, Wong CS, Andrews DM, Sloan EK, Parker BS, Bowtell DD, Smyth MJ, Moller A. Primary tumor hypoxia recruits CD11b+/Ly6Cmed/Ly6G+ immune suppressor cells and compromises NK cell cytotoxicity in the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3906–3911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma X, Wang M, Yin T, Zhao Y, Wei X. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote metastasis in breast cancer after the stress of operative removal of the primary cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:855. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]