Abstract

The incidence of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is especially increasing in high tuberculosis (TB) burden countries. Despite a high estimated CPA burden in Pakistan, actual data on CPA are not available. The aim of the current study is to determine the underlying conditions and clinical spectrum of CPA at a tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. This is a retrospective chart review study in patients admitted with CPA from January 2012 to December 2017. A total of 67 patients were identified during the study period. Mean age of CPA patients was 45.9 ± 15 years, 44 (65.7%) were male and 19 (28.4%) had diabetes. The most common type of CPA was simple aspergilloma (49.2%) followed by chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA) (44.7%). TB was the underlying cause of CPA in 58 (86.6%) patients followed by bronchiectasis caused by allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) 8 (11.9%). Aspergillus flavus was identified in 17 (47.2%), followed by A. fumigatus in 13 (36.1%) CPA patients. Isolation of multiple Aspergillus species was found in 10 (25.6%) patients. Itraconazole was given in 27 (40.3%) patients and a combination therapy of itraconazole and surgery was given in 21 (31.34%) patients. We found aspergilloma and CCPA as the most prevalent forms of CPA in our setting. Further large prospective studies using Aspergillus specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies testing are required for better understanding of CPA in Pakistan.

Keywords: chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, structural lung diseases, developing country, Pakistan

1. Introduction

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is increasingly being recognized as an infectious post-tuberculosis (TB) sequelae [1,2]. The spectrum of CPA includes simple aspergilloma, chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA), aspergillus nodules, sub-acute invasive aspergillosis (SAIA), and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA) [3,4]. In addition to TB, CPA can also affect patients with other pulmonary disorders such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, sarcoidosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis, healed abscess cavities, and prior infection by non-tuberculous mycobacteria [4,5]. Aspergillus fumigatus is mainly reported as a causative species, but non-A. fumigatus species such as A. niger and A. flavus infection have also been reported from many countries [6,7]. It has been estimated that patients with residual pulmonary cavities of ≥2 cm after TB treatment have a 20% chance of developing aspergillomas [8]. Recent studies conducted in high TB burden settings such as India and Uganda evaluating CPA in post-TB patients estimated CPA to be more common in cavitary disease [9,10]. Another study from Cuba also showed an association between high levels of Aspergillus immunoglobulin G (IgG) and the presence of cavities [11]. If left untreated, CPA is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [3,4,5].

Although Pakistan has a huge burden of TB, CPA still exists as an under-recognized entity in Pakistan with limited diagnostic and treatment expertise. A recent burden estimate of CPA from Pakistan reported a high prevalence of 39 cases per 100,000 people [12]. It is difficult to diagnose CPA in Pakistan due to the non-availability of Aspergillus-specific IgG and limited knowledge of clinicians regarding this disease entity; therefore, CPA is often misdiagnosed. A study evaluating CPA burden in active TB patients in Indonesia reported that around 18% of CPA patients are misdiagnosed as TB [13]. Recently modified criteria have been suggested for low-resource/income countries which define CPA on the basis of presence of one or more cavities with or without a fungal ball or nodules/pleural thickening on thoracic imaging, direct evidence of Aspergillus infection (microscopy or culture) or an immunological response to Aspergillus spp. and exclusion of alternative diagnoses, all present for at least three months along with chronic respiratory symptoms [14].

Clinical data on underling conditions, clinical characteristics, and spectrum of CPA from Pakistan, a high TB-burden country, are not available. Therefore, this study aims to report the underlying conditions and types/spectrum of CPA from a tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. This study provides some baseline knowledge that will help for better understanding and for future studies in Pakistan.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

This was a retrospective chart review study conducted at Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan from January 2012 to December 2017. All adult patients (>18 years) diagnosed as aspergillosis using the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision codes (ICD-9 1173) were identified from the medical records. CPA was diagnosed by using the diagnostic criteria proposed by Denning et al. for the resource constrained settings [14] as Aspergillus-specific IgG testing was not performed. CPA was further classified into (1) simple aspergilloma, (2) CCPA, (3) CFPA, (4) Aspergillus nodules, and (5) SAIA, based on definitions from Denning et al. [3]. Patients with invasive pulmonary and extra-pulmonary aspergillosis were excluded from the study. Patients who did not fulfill the above-defined criteria and had incomplete records were also not included. Data were collected on predesigned proforma with details of patient demographics, associated conditions, underlying lung pathologies, and radiological, microbiological, and treatment data. The ethical review committee of the Aga Khan University Hospital approved the study protocol before the commencement of the study.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted by using the SPSS (Release 19.0, standard version, copyright © SPSS; 1989–2002). A descriptive analysis was performed for demographic data presented as mean ± SD, for quantitative variables like age. Numbers (percentage) were calculated for qualitative variables; that is, gender, mortality, smokers, associated underlying disease, radiographic findings, isolated Aspergillus species, and respiratory complications.

3. Results

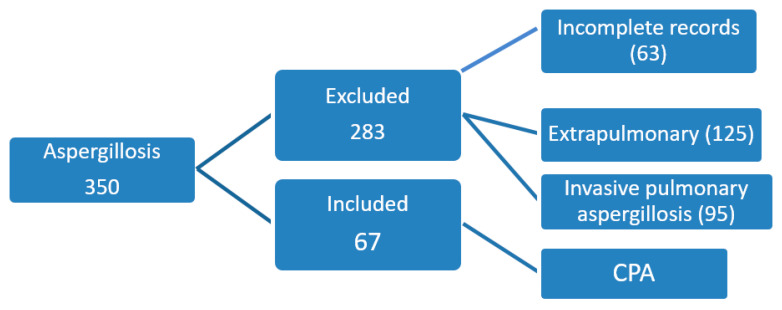

A total of 350 records were reviewed with the diagnosis of aspergillosis and 67 (19.1%) patients (male, 44; female, 23) fulfilled the criteria of CPA (Figure 1). Mean age of CPA patients was 45.9 ± 15 years (minimum 22 years and maximum 78 years). Cough was the predominant symptom noticed in 55 (82.0%) CPA patients followed by hemoptysis in 40 (59.7%) and weight loss in 34 (50.7%). Clinical, radiographical, and microbiological criteria were positive in 33 (49.2%) patients. Diabetes (DM) was present in 19 (28.4%) patients as an associated condition. Amongst the underlying lung conditions, previous TB was present in 58 (86.6%) CPA patients followed by bronchiectasis secondary to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) in 8 (11.9%) patients (Table 1). The most common form of CPA was simple aspergilloma (n = 33; 49.2%) followed by CCPA (n = 30; 44.7%). Culture was positive in 39 patients and Aspergillus flavus was the most frequently isolated species (n =17/39, 47.2%) followed by A. fumigatus (n = 13/39, 33.3%) and A. niger (n = 12/39, 30.7%). In 10 (25.6%) patients there was isolation of two or more Aspergillus species (Table 2). Itraconazole alone was used for treating 27 (40.3%) CPA patients and voriconazole alone in four (5.9%). Surgical excision with itraconazole therapy was administered in 21 (31.34%) patients and 9 (13.4%) patients underwent surgery alone. Five patients (7.4%) did not receive any treatment.

Figure 1.

Patient enrollment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients and diagnostic criteria of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA).

| Variables | Total n = 67 | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean) | 45.9 ± 15 years | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 44 | 65.7% |

| Female | 23 | 34.3% |

| Smoking status | ||

| Ex-smoker | 21 | 31.3% |

| Non-Smoker | 46 | 68.7% |

| Current smoker | 0 | - |

| Clinical Symptoms | ||

| Cough | 55 | 82.0% |

| Hemoptysis | 40 | 59.7% |

| Weight loss | 34 | 50.7% |

| Dyspnea | 24 | 35.8% |

| Fever | 22 | 32.8% |

| Anorexia | 7 | 10.4% |

| Chest pain | 9 | 13.4% |

| Associated Condition | n = 33 | 49.3% |

| DM | 19 | 28.4% |

| CLD | 2 | 3.0% |

| CRF | 2 | 3.0% |

| Malignancy | 3 | 4.5% |

| Inhaled steroid | 14 | 20.9% |

| Oral steroid | 11 | 16.4% |

| Underlying Lung Condition | ||

| Previous TB | 58 | 86.6% |

| ABPA bronchiectasis | 8 | 11.9% |

| Post-pneumonia bronchiectasis | 6 | 8.9% |

| COPD | 7 | 10.4% |

| Previous CTS surgery | 5 | 7.4% |

| Active TB | 2 | 2.9% |

| ILD | 2 | 2.9% |

| Sarcoidosis | 1 | 1.4% |

| Granulomatous polyangiitis | 1 | 1.4% |

| Diagnostic criteria | ||

| Clinical + Radiographic+ Histopathology | 28 | 41.7% |

| Clinical + Radiographic + Microbiology | 35 | 49.2% |

| Clinical + Radiographic+ Histopathology + Microbiology | 6 | 8.9% |

CTS: cardiothoracic surgery, DM: diabetes, CLD: chronic liver disease, CRF: chronic renal failure, TB: tuberculosis, ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ILD: interstitial lung disease.

Table 2.

Type and microbiological features for patients with CPA.

| n = Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Types of CPA | ||

| Simple aspergilloma | 33 | 49.2% |

| CCPA | 30 | 44.7% |

| CFPA | 3 | 4.4% |

| SAIA | 1 | 1.4% |

| Aspergillus species | n =39 | |

|

A. fumigatus

A. flavus A. niger A. terreus |

13 17 12 7 |

33.3% 43.5% 30.7% 17.9% |

|

Two or more Aspergillus species

A flavus + A. niger + A. terreus A. flavus + A. niger A. flavus + A. niger + A. fumigatus |

8/39 3 4 1 |

20.5% 20.0% 40.0% 10.0% |

CCPA: chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis, CFPA: chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis, SAIA: sub-acute invasive aspergillosis.

4. Discussion

This is the first study from Pakistan describing clinical spectrum and underlying associated conditions of CPA. We found that previous TB was the most common underlying lung condition and aspergilloma and CCPA were the most frequent types of CPA. A significant burden of CPA has been reported globally with most cases estimated in high TB burden countries. Actual data of CPA is not available from Pakistan, however recent estimates showed a burden of 39 cases/100,000 people [5,6]. Similar to the data from other countries, CPA in our cohort of patients also occurred most commonly in post-TB patients [3,4,15]. Data from India also suggested a significant burden of CPA in post-TB and asthmatic patients [2]. We also found post-ABPA bronchiectasis as an underlying cause in 11.9% of our CPA patients. Contrary to the countries where TB is endemic, COPD has been reported to be the most common risk factor of CPA in other countries [3,4,5]. Prior cardiothoracic surgery has also been reported to increase the risk of CPA [4,16,17]. In addition to TB, we also found COPD and previous cardiothoracic surgery as underlying conditions of CPA in our study population.

Diabetes remains an important associated disease in TB patients and is related with aggressive course and outcomes [18,19,20]. We found diabetes in 28.4% of our patients with CPA. It is well established through literature that diabetes is associated with cavitation, treatment failure, and relapses in TB patients. Patients with DM are prone to develop Aspergillus infection because of impaired immunity and greater structural lung damage [20]. The most prevalent form of CPA in our study was aspergilloma followed by CCPA. Literature also suggest these as the most common manifestations of CPA which can progress to CFPA if they remain untreated [3].

Aspergillus-specific IgG is usually positive in >90% of cases with CPA [3,14]. It has good positive predictive value and can differentiate infected from colonized individuals [21]. Unfortunately, this test is not available currently in our country and therefore IgG levels were not tested in these patients. The most common Aspergillus species in our study was A. flavus followed by A. fumigatus and A. niger. Data suggest A. fumigatus is the most frequently isolated species seen in CPA patients with A. niger and A. flavus as rare causes [4,5]. However, in many settings non-A. fumigatus species are a predominant cause of CPA similar to our patient population and therefore concerns have been raised regarding false negative IgG results in such populations [6,7]. The majority of our patients received either itraconazole or a combination of surgery with itraconazole. Due to its low cost, itraconazole is usually the first choice of treatment for CPA in our country, followed by voriconazole with a response rate of more than 50% [22,23]. The majority (33; 49.2%) of our patients underwent a lobectomy for uncomplicated aspergilloma.

This is the first report from Pakistan which studied the clinical characteristics of CPA patients. However, there were several limitations of this data. Firstly, this was a retrospective single center study. Secondly, due to non-availability, Aspergillus specific IgG was not detected, and the actual burden of CPA could be higher. Additionally, we were unable to see outcomes of these patients because of retrospective chart review. Time duration of developing CPA was not addressed in this study because of limitations of data availability. Finally, year-wise incidence could not be calculated as data regarding total number of TB patients or other baseline hospital parameters (such as patient days or 1000 discharges) were not available.

5. Conclusions

The majority of CPA patients are usually misdiagnosed as recurrence of TB due to similarities in clinical presentation. Additionally, the absence of an Aspergillus IgG test leads to further delay in diagnosis. Therefore, it is important to recognize CPA and raise awareness amongst clinicians in Pakistan where TB is endemic and CPA burden is been estimated to be high. Further large-scale prospective studies using Aspergillus-specific IgG testing are urgently required for better understanding of the prevalence of CPA in post-TB and other structural lung disease patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.I., M.I., and K.J.; Formal analysis, N.I.; Methodology, M.I.; Supervision, K.J.; Writing—original draft, N.I. and A.M.; Writing—review and editing, N.I., M.I., A.M., and K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Denning D.W., Pleuvry A., Cole D.C. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011;89:864–872. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.089441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal R., Denning D.W., Chakrabarti A. Estimation of the burden of chronic and allergic pulmonary aspergillosis in India. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denning D.W., Cadranel J., Beigelman-Aubry C., Ader F., Chakrabarti A., Blot S., Ullmann A.J., Dimopoulos G., Lange C. European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and European Respiratory Society. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: Rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;47:45–68. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith N.L., Denning D.W. Underlying conditions in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis including simple aspergilloma. Eur. Respir. J. 2011;37:65–872. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00054810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denning D.W., Riniotis K., Dobrashian R., Sambatakou H. Chronic cavitary and fibrosing pulmonary and pleural aspergillosis: Case series, proposed nomenclature change, and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;37:S265–S280. doi: 10.1086/376526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tashiro T., Izumikawa K., Tashiro M., Takazono T., Morinaga Y., Yamamoto K., Imamura Y., Miyazaki T., Seki M., Kakeya H., et al. Diagnostic significance of Aspergillus species isolated from respiratory samples in an adult pneumology ward. Med. Mycol. 2011;49:581–587. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.548084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahid M., Malik A., Bhargava R. Prevalence of aspergillosis in chronic lung diseases. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2001;19:201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.British Thoracic and Tuberculosis Association Aspergilloma and residual tuberculous cavities—The results of a resurvey. Tubercle. 1970;51:227–245. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(70)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page I.D., Byanyima R., Hosmane S., Onyachi N., Opira C., Richardson M., Sawyer R., Sharman A., Denning D.W. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis commonly complicates treated pulmonary tuberculosis with residual cavitation. Eur. Resp. J. 2019;53:1801184. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01184-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sehgal I.S., Dhooria S., Choudhary H., Aggarwal A.N., Garg M., Chakrabarti A., Agarwal R. Efficiency of A fumigatus-specific IgG and galactomannan testing in the diagnosis of simple aspergilloma. Mycoses. 2019;62:1108–1115. doi: 10.1111/myc.12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beltrán Rodríguez N., San Juan-Galán J.L., Fernández Andreu C.M., María Yera D., Barrios Pita M., Perurena Lancha M.R., Velar Martínez R.E., Illnait Zaragozí M.T., Martínez Machín G.F. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Patients with Underlying Respiratory Disorders in Cuba—A Pilot Study. J. Fungi. 2019;5:18. doi: 10.3390/jof5010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jabeen K., Farooqi J., Mirza S., Denning D.W., Zafar A. Serious fungal infections in Pakistan. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017;36:949–956. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2919-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setianingrum F., Rautemaa-Richardson R., Shah R., Denning D.W. Clinical outcome of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis patients managed surgically. In Proceedings of the 9th Trends in Medical Mycology Conference, Nice, France, 11–14 October 2019. J. Fungi. 2019;5:95. doi: 10.3390/jof5040095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denning D.W., Page I.D., Chakaya J., Jabeen K., Jude C.M., Cornet M., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Bongomin F., Bowyer P., Chakrabarti A., et al. Case definition of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in resource-constrained settings. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018;24 doi: 10.3201/eid2408.171312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosmidis C., Denning D.W. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax. 2015;70:270–277. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamura A., Suzuki J., Fukami T., Matsui H., Akagawa S., Ohta K., Hebisawa A., Takahashi F. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to lobectomy for lung cancer. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2015;21:650–656. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes G.E., Novak-Frazer L. Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis—Where Are We? And Where Are We Going? J. Fungi. 2016;2:18. doi: 10.3390/jof2020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dooley K.E., Chaisson R.E. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: Convergence of two epidemics. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2009;9:737–746. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70282-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiménez-Corona M.E., Cruz-Hervert L.P., García-García L., Ferreyra-Reyes L., Delgado-Sánchez G., Bobadilla-Del-Valle M., Canizales-Quintero S., Ferreira-Guerrero E., Báez-Saldaña R., Téllez-Vázquez N., et al. Association of diabetes and tuberculosis: Impact on treatment and post-treatment outcomes. Thorax. 2013;68:214–220. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker M.A., Harries A.D., Jeon C.Y., Hart J.E., Kapur A., Lönnroth K., Ottmani S.E., Goonesekera S.D., Murray M.B. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: A systematic review. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: A systematic review. BMC. Med. 2011;9:81. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uffredi M.L., Mangiapan G., Cadranel J., Kac G. Significance of Aspergillus fumigatus isolation from respiratory specimens of nongranulocytopenic patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2003;22:457–462. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0970-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida K., Kurashima A., Kamei K., Oritsu M., Ando T., Yamamoto T., Niki Y. Efficacy and safety of short- and long-term treatment of itraconazole on chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis in multicenter study. J. Infect. Chemother. 2012;18:378–385. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0414-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal R., Vishwanath G., Aggarwal A.N., Garg M., Gupta D., Chakrabarti A. Itraconazole in chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis: A randomised controlled trial and systematic review of literature. Mycoses. 2013;56:559–570. doi: 10.1111/myc.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]