Graphical abstract

Keywords: Plastic pollution, Contaminant migration, Terrestrial ecosystem, Environmental remediation, Virus, Risk management

Highlights

-

•

Nanoplastics (NPs) are currently less-explored compared to microplastics (MPs).

-

•

Co-transport mechanisms of NPs with bacteria and viruses have been proposed.

-

•

Aging and aggregation characteristics of NPs have been assessed.

-

•

DPSIR framework describes the relationships between NPs, ecosystems and humans.

-

•

Further studies should focus on naturally weathered NPs.

Abstract

Tiny plastic particles considered as emerging contaminants have attracted considerable interest in the last few years. Mechanical abrasion, photochemical oxidation and biological degradation of larger plastic debris result in the formation of microplastics (MPs, 1 μm to 5 mm) and nanoplastics (NPs, 1 nm to 1000 nm). Compared with MPs, the environmental fate, ecosystem toxicity and potential risks associated with NPs have so far been less explored. This review provides a state-of-the-art overview of current research on NPs with focus on currently less-investigated fields, such as the environmental fate in agroecosystems, migration in porous media, weathering, and toxic effects on plants. The co-transport of NPs with organic contaminants and heavy metals threaten human health and ecosystems. Furthermore, NPs may serve as a novel habitat for microbial colonization, and may act as carriers for pathogens (i.e., bacteria and viruses). An integrated framework is proposed to better understand the interrelationships between NPs, ecosystems and the human society. In order to fully understand the sources and sinks of NPs, more studies should focus on the total environment, including freshwater, ocean, groundwater, soil and air, and more attempts should be made to explore the aging and aggregation of NPs in environmentally relevant conditions. Considering the fact that naturally-weathered plastic debris may have distinct physicochemical characteristics, future studies should explore the environmental behavior of naturally-aged NPs rather than synthetic polystyrene nanobeads.

1. Introduction

Made of various synthetic or semi-synthetic organic polymers, plastics are malleable materials capable of being molded into solid objects of various types and sizes. Due to the ease of manufacture, high stability and versatile properties, plastics have been used in a wide range of products. Thus, annual production of plastics keeps growing, reaching 359 million tons in 2018 (PlasticsEurope, 2019). Despite the fact that plastic recycling and management policies are improving, improper handling of plastic disposal is still a global trend, accounting for the unregulated release into the environment (PlasticsEurope, 2019; Barría et al., 2020). Due to the hydrophobicity, physical and chemical resistance, plastics can be transported from terrestrial ecosystems to aquatic ecosystems. Plastics have been found in all kinds of environmental media, including the surface freshwater and the sediment, marine surface water and the seabed, groundwater, soil and even the atmosphere (Alimi et al., 2018; Astner et al., 2019; Ng et al., 2018; Song et al., 2019; Hurley and Nizzetto, 2018; Prata, 2018; Carr et al., 2016; Eerkes-Medrano et al., 2015).

Once released into the environment, plastic particles are subjected to weathering and fragmentation (section 2.2). Various natural forces, such as the mechanical forces of water, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and biological metabolism lead to the fragmentation into smaller plastic particles, namely microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs). MP is defined as the plastic particles with the size ranging from 1 μm to 5 mm (Schwaferts et al., 2019; Collignon et al., 2014; Browne et al., 2007). Concerning NPs, there is still debate on its definition. Some scholars suggest that a definition of nanoparticles (from 1 nm to 100 nm) should be extrapolated to define NPs (European Commission, 2011; Ivleva et al., 2017), while others adopted the whole nanometer range (from 1 nm to 1000 nm) (Schwaferts et al., 2019; Gigault et al., 2018; da Costa et al., 2016). In this review, we adopt the latter definition and regard sub-micron plastic particles (with diameter ranging from 100 nm to 1 μm) also as NPs.

Due to the recalcitrant characteristics of plastic particles, the environmental fate and the toxic effects of MPs have been widely explored. Many review articles have focused on various fields, including the sources (Bradney et al., 2019), distribution (Fu et al., 2020a), migration (Guo et al., 2020), bioaccumulation (Xu et al., 2020), toxicity (Chen et al., 2020), ecological risks (Ma et al., 2020a), and remediation strategies (Zhang et al., 2020a) of MPs. In comparison, NPs are much less explored. Downsizing the plastic debris from micro to nano scale will result in a shift in physicochemical properties (section 2.2). Besides, the environmental behavior (such as aggregation and migration), bioaccumulation features, and toxicity of plastic particles are highly dependent on the size. Further investigations on NPs are necessary.

Similar with investigations on MPs, current studies regarding NPs have focused more on the marine ecosystem, especially the toxic effects of NPs on marine organisms, including bacteria, algae and fish (Barría et al., 2020; Rios Mendoza et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2020). Research on NPs in terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems is still limited. This review summarizes the current research status of NPs with focus on less-explored, poorly understood fields, especially the migration of NPs in terrestrial systems (e.g., transport and aggregation in the porous media), weathering and aging processes, plant accumulation (either in freshwater or terrestrial ecosystems), and the toxic effects of attached contaminants (i.e., organic contaminants, metals and pathogens). Furthermore, possible mechanisms involved in the co-transport behavior of NPs with heavy metals, organic molecules and human pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses have been put forward. To better comprehend the relationships between nanoplastics, ecosystems and the human society, an integrated DPSIR (driving forces – pressures – states – impacts – responses) framework is proposed. In addition, potential risk mitigation strategies, and the feasibility of extrapolating the remediation strategies towards other contaminants (e.g., immobilization of organic herbicides using biochar) to NP contamination are discussed critically.

2. Characteristics of NPs

2.1. Separation and analysis

Methodological challenges associated with the separation and analysis of NPs hinder the development of this field. High-quality pre-treatment is necessary for the analysis of these tiny particles. Environmental samples of NPs can cover a wide range of media, including wastewater, drinking water, sediments, soils, sludge, compost and even atmospheric deposition (Prata, 2018; Xu et al., 2019). Separation of NPs is required for most studies, and the first step is digestion (Table 1 ). Although acid/alkaline/oxidizing agents can be used for chemical digestion, the change in solution ionic strength may result in the aggregation of NPs (Rist et al., 2017). To overcome this obstacle, a milder approach that uses enzymes such as Proteinase K can be used for decomposition of biological tissues (Correia and Loeschner, 2018).

Table 1.

Pre-treatment and analysis methods for NPs. Information obtained from (Schwaferts et al., 2019; Correia and Loeschner, 2018; Gagné et al., 2019; Gigault et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2020; Pinto da Costa et al., 2019; Sullivan et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2019).

| Method | Description | Applicability (diameter range) | Advantages | Obstacles | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | |||||

| Chemical digestion | Remove the matrix using acid/base/oxidant | Any | Potent | Change the ionic strength, leading to aggregation Influence the fluorescence signal of labelled plastics | (Rist et al., 2017) |

| Biological disgestion | Remove the matrix using enzymes such as Proteinase K | Any | Mild, cause less or no aggragation | Cannot remove the non-degradable matrix | (Correia and Loeschner, 2018) |

| Ultrafiltration | Collect nanoplastics using nano-porous membranes under external pressure (facilitate the flow) | 5−50 nm | Able to process large volumes of water, minimize aggragation | Nanoplastic may interact with membrane | (Ter Halle et al., 2017) |

| Ultracentrifugation | Concentrate nanoplastics using centrifugal forces | Any | Easy to operate | Small sample volumes (usually below 100 mL) | (Vauthier and Bouchemal, 2009) |

| Evaporation | Remove solvent at reduced pressure | Any | Easy to operate | Unable to remove dissolved matter | (Magrì et al., 2018) |

| Field Flow Fractionation (FFF) | Separate nanoparticles in a flow channel due to the variance in diffusivity | 1−1000 nm | Can be coupled to online detectors such as DLS and MALS (simultaneous separation and detection) | Complicated, difficult to operate | (Correia and Loeschner, 2018) |

| Analysis | |||||

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Analyze particle size using fluctuation which is caused by Brownian motion | 1−3000 nm | Easy to operate, fast, in-situ | Does not provide any chemical information | (Oriekhova and Stoll, 2018) |

| Multiangle Laser Scattering (MALS) | Analyze particle size through scattered laser light at various angles | 10−1000 nm | Can be coupled to separation methods (e.g., AF4) | Sensitive to environmental disturbance | (Gigault et al., 2017) |

| Laser Diffraction (LD) | Analyze particle size based on the Fraunhofer diffraction theory | 10 nm-10 mm | Large size range, easy to operate, fast | Based on spherical model | (Xu, 2015) |

| Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) | Analyze particle size (based on Brownian motion theory) with digital camera and microscope | 10−1000 nm | Visualize the motion of nanoplastics | Based on spherical model | (Lambert and Wagner, 2016) |

| Electrophoretic Light Scattering (ELS) | Determine the surface charge by measuring the fluctuation generated by nanoplastic movement in the electric field | 1−3000 nm | Easy to operate, fast, in-situ | Sensitive to environmental disturbance | (Oriekhova and Stoll, 2018) |

| Raman Microspectroscopy (RM) | Investigate the size and shape, chemical identification | > 100 nm | Higher resolution compared with FT-IR; investigate the size, shape and chemical properties simultaneously | Qualitative rather than quantitative; the diffraction limit of the laser spot hinders the imaging of smaller NPs | (Sobhani et al., 2020) |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Investigate the surface morphology as well as the shape and size | Any | High resolution of images | Sample charging may be significant, Quantification is difficult | (Oriekhova and Stoll, 2018) |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Investigate the interior information of nanoplastics as well as the shape and size | Any | High resolution of images | Quantification is difficult | (Gigault et al., 2018) |

| Energy-dispersive X-ray Spectrometry (EDS) | Elemental composition | Any | Can be coupled to SEM and TEM | Some elements cannot be detected precisely (e.g., C) | (Gniadek and Dąbrowska, 2019) |

| Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS) | Chemical identification | LOD: ng/μg | Can be coupled to separation methods (e.g., AF4) | High-quality pre-concentration is required | (Mintenig et al., 2018) |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) | Functional groups | Bulk measurement | Easy to operate | Impossible to characterize a certain nanoplastic particle | (Hernandez et al., 2019) |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Surface chemical properties | Bulk measurement | Surface characterization | Impossible to characterize a certain nanoplastic particle | (Hernandez et al., 2019) |

After digestion, preconcentration and separation steps are needed. According to the separation mechanisms, these methods can be divided into two categories, namely size-based and density-based separation. As for size-based separation, the most widely used methods for nanoplastic enrichment are filtration (Fig. 1 c) and field flow fractionation (FFF) (Fig. 1b) (Table 1). In (ultra)filtration systems, particles larger than the nano-sized membrane is collected (Fig. 1c), and an external pressure could facilitate the water flow, thus increasing the operation speed. Field flow fractionation is a separation method where a field (e.g., electrical, centrifugal, gravitational, etc.) is applied perpendicularly to the fluid suspension crossing a long channel, resulting in the separation of particles present in the suspension depending on the differing mobilities under the external field-induced force (Correia and Loeschner, 2018; Giddings et al., 1976). The most widely used FFF system is the Asymmetrical flow field flow fractionation (AF4), where the external field is the cross flow created by the asymmetrical wall (only the bottom wall of the channel is permeable) (Fig. 1b). Due to the variance in diffusivity of particles (which is determined by size and particulate density), different particles are retained for different durations in the AF4 system (Fig. 1b). The advantage of AF4 is that it can separate and characterize nanoparticles simultaneously through coupling to online detectors (Schwaferts et al., 2019; Correia and Loeschner, 2018). Compared with size-based separation strategies, density-based ones such as ultracentrifugation is seldom used in studies related to nanoplastics. This is probably because this technique has the limitation that it only processes small sample volumes (i.e., < 100 mL), limiting its applicability for environmental samples with low NP concentrations that require a much larger volume to obtain adequate amount of NPs (Schwaferts et al., 2019).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of various separation methods for NPs: (a) Differential separation, a typical ultracentrifugation method. Reproduced with permission from (Li et al., 2018). Copyright 2018 Elsevier; (b) Separation of particles using asymmetrical flow field flow fractionation (AF4). Smaller particles possess higher diffusion coefficients, which stabilize further away from the membrane. Thereby, they are subjected to faster steamlines than larger ones, and exit the channel more quickly. Reproduced with permission from (Müller et al., 2015). Copyright 2015 Frontiers Media; (c) Isolation of NPs from facial scrubs using five filtration steps. Reproduced with permission from (Hernandez et al., 2017). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

A number of techniques can be used to analyze physicochemical properties of NPs (Table 1). Laser light scattering is the most widely used method for particle size assessment. When the laser passes through the suspension of NPs, a fluctuation of its intensity can be induced by the Brownian motion, which is dependent on the hydrodynamic diameter with NPs. Electron microscopy is widely adopted to investigate the surface morphology of NPs. Since the wavelength of electrons is much shorter than that of visible light, electron microscopies possess much higher resolutions (several nanometers) as compared with optical microscopies (> 1 μm). Besides, electron microscopies can be coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectrometers (EDS) to investigate elemental distributions simultaneously. Although several conventional characterization methods such as Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) cannot be used to characterize a certain nanoplastic particle due to their size detection limits, they can provide much useful information for bulk samples of NPs (Schwaferts et al., 2019). For more detailed discussion regarding the separation and characterization methods of NPs, we refer readers to Schwaferts et al. (2019) and Fu et al.(2020b).

2.2. Physicochemical properties: from micro to nano

The size of a plastic particle is the dominant characteristic determining its environmental fate (e.g., migration) (Song et al., 2019; He et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2020a). Besides, bioaccumulation and toxicity can be size-dependent (Kim et al., 2020; Lei et al., 2018; Sendra et al., 2019). Considering that NPs mainly originate from the fragmentation and transformation of larger plastic particles (secondary NPs, section 3.1), investigating the downsizing mechanisms will be helpful for a better understanding of NPs.

NPs can be generated through the mechanical abrasion processes. The breakdown of daily-use polystyrene products by household blender generate considerable amounts of NPs (Ekvall et al., 2019). Fragmentation of solid plastic wastes and MPs generate NPs in sewer system due the turbulence of water flow and mechanical devices in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) (Lv et al., 2019). The natural fragmentation of larger plastic pieces can also be achieved in the sea swash zone (Efimova et al., 2018). The mechanical fragmentation of macro- and micro-sized plastic particles are mainly caused by the formation of cracks (Enfrin et al., 2020; Julienne et al. 2019). The theory of crack-induced solid failure can therefore be adopted to depict this process, and the size of resulting NPs can be calculated using the following equation (Eq. 1) (Enfrin et al., 2020; Grady, 2015):

| (1) |

where is the size of NPs, is the stress intensity factor of the plastic material, is the density, represents the elastic wave speed, refers to the stain of plastic material, which is dependent on the applied stress.

Hydrolysis (react with water) is another potential mechanism accounting for NP generation, yet it may not be the most powerful one at reducing the sizes of plastics (Andrady, 2011). In comparison, degradation initiated by UV irradiation is a very efficient downsizing mechanism. The photodegradation of plastics is mainly induced by reactive oxygen species. The decrease in particle size may be due to the chain scission by attacks from free radicals, such as hydroxyl (·OH), alkyl (R·), alkoxyl (RO·) and peroxyl (ROO·) radicals produced from the UV light. Possible reaction mechanisms for free-radical induced fragmentation include three steps (Eq. (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (9) (Liu et al., 2019a; Bracco et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2019):

Step 1-initiation

| (2) |

Step 2-propagation

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Step 3-termination

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Biological degradation and fragmentation of large plastic pieces and MPs by marine and terrestrial animals could also generate NPs in environment. The ingestion of plastic MPs and potentially NPs by marine organisms has been found among zooplankton, fish, shrimps and other animals (Wright et al., 2013; Lusher et al., 2013; Tanaka and Takada, 2016). Fragmentation or degradation of MPs into NPs has been reported in Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) exposed to polyethylene MPs (31.5 μm) together with algal food. After ingestion, NPs of 150−500 nm size were formed, which were found in the digestive gland (Dawson et al., 2018). Reduction of MPs into smaller sizes has been observed in the common earthworm (Huerta Lwanga et al., 2017) and snails (Song et al., 2019), although fragmentation of MPs into NPs was not considered in these studies due to limitation of excess tools.

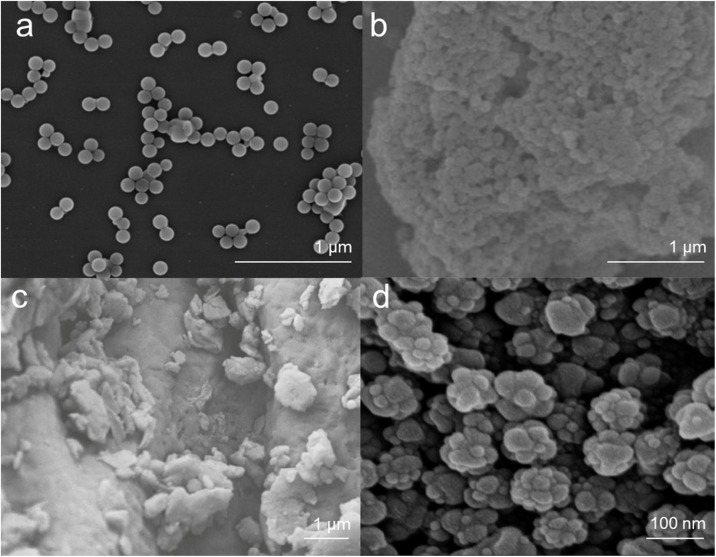

The morphology NPs are mainly determined by their origins (i.e., natural weathering vs synthetic fabrication). NPs from different origins have diverse shapes (Fig. 2 ). Many studies regarding the migration, bioaccumulation and toxicity have adopted commercially-available NPs, which exhibit ideal spherical morphology in most cases (Fig. 2a, b). Another type of synthetic NPs is the metal-doped nanoplastics with a raspberry-like morphology (Fig. 2d). However, in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, NPs originate mainly from the weathering and fragmentation of larger plastic particles, rather than the controlled synthesis. NPs resulting from the weathering of large plastic particles possess much rougher morphologies (Fig. 2c). Due to natural forces such as mechanical forces of water (Koelmans et al., 2015), UV radiation (Gniadek and Dąbrowska, 2019), and biological metabolism (Austin et al., 2018), the shapes of resulting NPs become hardly smooth and spherical.

Fig. 2.

Morphologies of various NPs: (a) commercially available polystyrene (PS) nano-bead particles (Lei et al., 2018); (b) commercially available polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) nanoparticles with diameter of 120 nm (Liu et al., 2019b); (c) nano-sized polystyrene (PS) particles attached on surface of polystyrene spherule, which were fragmented from the expanded polystyrene spherules by accelerated mechanical abrasion for a month (Koelmans et al., 2015); (d) synthetic metal-doped polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanoparticle with a raspberry-like appearance (Mitrano et al., 2019). All images are reproduced with permission.

Downsizing of plastic particles from micro to nano scale can also lead to a shift in chemical properties, especially surface functional groups. As shown in Eq. (2)-Eq. (9), reactive oxygen species are generated during the photodegradation process. This may result in an increase in oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl, carbonyl and hydroxyl on the surface of NPs (Liu et al., 2019a, c). The changes in surface functional groups alter the hydrophobicity and surface charges of NPs, which may affect the migration (Dong et al., 2019a), aggregation (Yu et al., 2019; Tallec et al., 2019), contaminant adsorption (Bradney et al., 2019), bioavailability (Nolte et al., 2017) and toxicity (Zhang et al., 2019a; Della Torre et al., 2014) of NPs. It is therefore necessary to fully understand the weathering process of plastic particles. However, current studies mostly focus on the environmental behavior and toxic effects of synthetic spherical NPs since they can be easily obtained. It is argued that results from current studies may not reveal the behavior of naturally weathered NPs under field conditions (section 6).

3. Environmental behavior of NPs

3.1. Potential sources

Like MPs, the sources of NPs in environment can be categorized as either primary or secondary, depending upon whether they are <1000 nm before entering the natural environment, or become this size via the degradation and fragmentation of larger pieces of plastic litter or MPs, respectively. The primary source of NPs could include nanometer-sized fragments from clothes washing, nano-sized particles released from plastic tea bags (Hernandez et al., 2019) and small fragments from plastic microbeads and industrial powders, etc. The secondary is likely due to NP generation from plastic wastes and MPs via various ways in environment (section 2.2).

As man-made products, plastics mostly originate from terrestrial systems. However, due to the accumulation of plastic particles in sewage and effluents, they may end up accumulating in aquatic ecosystems. It is estimated that over 80 % of marine plastics are from land-based sources, such as coastal landfill operations, NPs carried by rivers and streams, biosolid and compost applications, and improper disposal of untreated sewage (Barría et al., 2020; Ganesh Kumar et al., 2020). Besides, direct marine-based sources include discharging of litters from ships/boats and fishing nets (da Costa et al., 2016; Ganesh Kumar et al., 2020).

In this sense, understanding the terrestrial origin of NPs is crucial. One of the main sources of NPs is the domestic activities. Tiny fibers of polyester, nylon, acrylic and spandex are carried off to wastewater treatment plants during clothes laundry (UNEP, 2018). Fragmentation of microbeads used in shampoos and scrubs release considerable amounts of NPs (Hernandez et al., 2017). Even plastic tea bags could release billions of NPs (Hernandez et al., 2019). Apart from domestic origins, industrial sources include the direct fabrication of NPs (Yoshino et al., 2012) and feedstocks of plastic products (da Costa et al., 2016; Phuc et al., 2014). In addition, agricultural activities contribute to the release of NPs. Application of sewage sludge as fertilizers represents a significant source (Alimi et al., 2018; Hurley and Nizzetto, 2018), while plastic mulching (Ng et al., 2018) and polymer-coated slow release fertilizers and pesticides (Bradney et al., 2019) present other potential origins of NPs.

3.2. Migration characteristics

Although migration characteristics of NPs in aquatic ecosystems are poorly investigated, methods and results from MPs may provide some insights in this field. Considering the vastness of oceans, models have been developed to predict the migration of MPs in marine ecosystems. Both theoretical and empirical models indicate that the ocean currents redistribute the plastic particles in surface oceanic waters, which will accumulate in five major “garbage patches” located in North and South of Atlantic, North and South of Pacific, and Indian Oceans (Fig. S1) (Mountford and Morales Maqueda, 2019; Hale et al., 2020; Lebreton et al., 2012; Sherman and Van Sebille, 2016; Maximenko et al., 2012). However, some scholars argued that an underestimation of plastics will occur if models focus merely on the surface ocean (Hale et al., 2020; Jambeck et al., 2015; Kanhai et al., 2019). Instead, models should also take deep waters, coastal sediments, and deep-sea sediments into account. A comprehensive review of migration characteristics of microplastics in the ocean is provided elsewhere (Hale et al., 2020).

For terrestrial ecosystems, current studies have mainly focused on the migration of NPs in porous media (Table 2 ). Although both artificial (e.g., quartz sand) and natural (e.g., natural sand, soil) solid materials can be used by these studies, the latter is preferred due to a more realistic size distribution. The transport of NPs is affected by several parameters, including particle size, ionic strength, surface functional groups of NPs, and organic matter (Table 2). Song et al. (2019) observed a trend of higher mobility of larger NPs (200 nm vs 50 nm) due to greater particle stability. An increase in ionic strength inhibits NP transport, since the compression of electrical double layer results in the formation of aggregates (Wu et al., 2020a; Hu et al., 2020). Dong et al. (2019a) found that retention of functionalized plastic particles in saturated sand followed the order of amino- > sulfonic- > carboxyl-modified NPs. They suggested that surface functional groups of NPs affect their affinity towards organic matter and ions in the aqueous phase, which may lead to different retention and migration rates. Carboxyl groups favored the adsorption of inorganic ions, hydrophilic contaminants, dissolved organic matter and suspended organic matter, while amino groups inhibited the adsorption of suspended organic matter and inorganic ions (Song et al., 2019). As shown in Table 2, addition of humic acid, a fraction of natural organic matter, could significantly enhance the migration of NPs (Dong et al., 2019a). This is because organic matter forms an eco-corona layer (coating) on NP surfaces, which prevents plastic particles from aggregation (section 3.3) and improves stability of NPs through enhanced steric and electrostatic repulsion (Alimi et al., 2018; Oriekhova and Stoll, 2018; Dong et al., 2019a). However, not all types of organic matter will enhance migration. Song et al. (2019) observed that suspended organic matter increased the stability and mobility of NPs, while dissolved organic matter decreased both. This was probably because that the coating of dissolved organic matter lowered the electrostatic repulsion between NPs and the sand, which allowed the attractive forces to be dominant, including Van der Waals force, organic polymer bridging, cation bridging, and electrostatic attraction (from positively-charged minerals).

Table 2.

Migration characteristics of NPs in porous media.

| NPs (size, nm) | Diameter of NPs (nm) | Solid phase | Aqueous phase | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene with fullerene (C60) | 200 | Natural sea sand (average diameter 0.45 mm, porosity 44.88 %) | Artificial seawater (salinity 35 PSU) | NPs facilitated C60 transport through increased colloidal ζ-potential | (Dong et al., 2019b) |

| Functionalized polystyrene (carboxyl, sulfonic, amino) | 200 | Natural sea sand (average diameter 0.45 mm, porosity 44.88 %) | Artificial seawater (salinity 35 PSU) | Addition of humic acid significantly promoted the migration of NPs through enhanced steric repulsion | (Dong et al., 2019a) |

| Polystyrene with E. coli | 20, 200 | Quartz sand (diameter ranging from 0.3 to 0.425 mm, porosity 0.42) | NaCl (10, 50 mmol/L) and CaCl2 (1, 5 mmol/L) solutions | NPs increased bacterial transport at high ionic strength conditions. The adsorption of NPs on bacteria induced the repel effect that facilitated the migration of E. coli | (He et al., 2018) |

| Polystyrene with naphthalene | 121.9 | Quartz sand (average diameter 0.6 mm, porosity 0.44) | NaCl solution (0.5 5, 50 mmol/L) | Naphthalene decreased the mobility of NPs through charge-shielding | (Hu et al., 2020) |

| Polystyrene with sewage sludge | 187 | Soil | Water | NPs were detached jointly with organic matter from the sludge during the artificial rainfall | (Keller et al., 2020) |

| Aged polystyrene (UV or O3) | 487.3 | Loamy sand soil | Water | Greater mobility of aged NPs was the result of the surface oxidation, which increased surface charge negativity and hydrophilicity | (Liu et al., 2019c) |

| Polystyrene | 100 | Soil (45 % sand, 36 % silt, and 19 % clay) | Water | NPs enhanced the migration of non-polar and weakly-polar molecules (e.g., pyrene, 2,2’,4,4’-tetrabromodiphenyl ether) in soil, while did not affect the transport of polar molecules (e.g., bisphenol A) | (Liu et al., 2018) |

| Functionalized polystyrene (carboxyl, amino) | 50, 200 | Agriculture-impacted shallow sandy aquifer | Natural groundwater | The suspended organic matter increased both the particle stability and mobility, while the dissolved organic matter reduced both | (Song et al., 2019) |

| Carboxylate-modified polystyrene | 20, 200 | Quartz sand (with 0.5 % biochar/magnetic biochar addition) | NaCl solution (0.1 mmol/L) | Biochar/magnetic biochar amendment decreased the mobility of NPs | (Tong et al., 2020a) |

| Carboxylate-modified polystyrene | 20, 200 | Quartz sand (diameter ranging from 0.3 to 0.425 mm) | NaCl solution (5, 25 mmol/L) | Biochar decreased the mobility of NPs through the formation of heteroaggregates | (Tong et al., 2020b) |

| Polystyrene | 100 | Desert soil, red soil and black soil | NaCl (1, 5, 10, 20 mmol/L) and CaCl2 (1, 2, 5 mmol/L) solutions | Retention of NPs was positively correlated with Fe/Al oxides contents, and negatively correlated with soil pH | (Wu et al., 2020a) |

On the one hand, co-existing contaminants/amendments affect the mobility of NPs. Addition of biochar in quartz sand or soils resulted in decreased mobility of NPs, which was due to the formation of heteroaggregates involving biochar and NPs (Tong et al., 2020a, b). Sewage sludge application as a soil fertilizer may lead to elevated mobility of NPs owing to the release of dissolved organic matter (Keller et al., 2020). Adsorption of naphthalene promoted the retention of NPs, which was attributed to the partial shielding of surface charge by the adsorbed nonpolar naphthalene molecule (Hu et al., 2020). On the other hand, NPs may also affect the migration of heavy metals, organic molecules and even pathogens such as bacteria and viruses in porous media. Although no available data is available regarding the co-transport of NPs and heavy metals, it is inferred that weathered NPs may favor the transport of heavy metals in porous media, since the oxidized surfaces possess more oxygen-containing functional groups, favoring the surface complexation between NPs and metal cations (Liu et al., 2019c). Sorption of dissolved organic matter (DOM) onto NP surface also promotes heavy metal complexation (section 4.2.2), leading to the mobilization of heavy metals through NP-metal co-transport. NPs may interact with organic molecules through various ways, including heteroaggregation, hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic interactions. Dong et al. (2019b) have observed that polystyrene NPs act as a vehicle for the transport of fullerene (C60) through the decrease in ζ-potential (formation of NP-C60 heteroaggregates) (Table 2). Liu et al. (2018) have noticed that polystyrene NPs could enhance the migration of non-polar and weakly-polar molecules (e.g., pyrene, 2,2′,4,4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether) in soil, while revealing no significant effect on the transport of polar molecules (e.g., bisphenol A). This is because non-polar and weakly-polar molecules can be adsorbed in the inner matrices of polystyrene’s glassy polymeric structure, resulting in physical entrapment of these organic contaminants. Co-transport of NPs and pathogens in soil threatens human health. With the outbreak of novel coronavirus (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2), the presence of human pathogens in environmental compartments and their potential risks (e.g., groundwater contamination as a result of soil-water transport, human inhalation due to soil-air transport) have raised much concern (Núñez-Delgado, 2020; Wu et al., 2020b). Limited evidence has shown that the adsorption of NPs on bacteria facilitates the migration of E. coli through the repelling effect (Table 2) (He et al., 2018). It is hypothesized that NPs may affect the mobility of bacteria and virus through various ways. Firstly, suspended NPs in the soil solution repel pathogens from approaching the soil colloid surface, thus increasing their mobility. In addition, NPs may adsorb to the pathogen surface, forming a plastic coating that prevents the formation of large pathogen-pathogen aggregates. NPs may also compete with pathogens for binding sites on soil colloids directly, promoting the desorption and migration of bacteria and viruses. More studies on co-transport of NPs and pathogens are needed before drawing a clear conclusion how NPs in soil and sand affect the mobility of bacteria and viruses.

3.3. Weathering and aggregation

The environmental fate of NPs is mainly governed by the weathering and the aggregation processes. Various stressors (environmental factors), such as the heat, water, UV irradiation, oxidants, microorganisms, or the combination of these causes the aging of NPs in the environment (Lambert and Wagner, 2017). An elevation in temperature will accelerate the weathering of NPs as per the Arrhenius relationship (Geburtig et al., 2019). The shear forces of the water cause the mechanical fragmentation (physical weathering) of NPs (section 2.2). Artificial aging using UV and O3 co-exposure resulted in much rougher morphology and more oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carbonyl, carboxyl) as compared with pristine NPs (Liu et al., 2019c). During this abiotic oxidation process, reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radical (O•H), singlet oxygen (1O2) and superoxide radical (•O2 −) induced the chain reactions, which degraded the structure of NPs. Furthermore, oxygen was introduced to the surface of NPs, resulting in an increased number of oxygen-containing functional groups (Liu et al., 2019c; Mao et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Microorganisms may also play vital roles in the biological weathering of NPs (section 2.2) through the colonization (plastisphere, section 4.2.3) and the utilization of the polymer matrix as a food source (Lambert and Wagner, 2017; Amaral-Zettler et al., 2020; Roager and Sonnenschein, 2019).

Aggregation is a key issue in understanding the environmental fate of NPs. Evidence has shown that NPs can form milli-sized (mm-sized) aggregates in ecosystems (Wegner et al., 2012). In addition, formation of heteroaggregates with inorganic colloids or organic matter lead to either settlement or migration of NPs (Oriekhova and Stoll, 2018; Dong et al., 2019b; Li et al., 2019). In order to describe the aggregation process of NPs, the Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory (Derjaguin and Landau, 1993; Verwey, 1947) has been widely adopted by various studies. The DLVO theory proposes that two independent forces, Van der Waals force (Eq. 11) and the electrostatic double layer force (Eq. 12) determine the stability of suspended particles (Liu et al., 2019a; Cai et al., 2018; Gregory, 1975, 1981):

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

where is the total interaction energy, is the Van der Waals interaction energy, and represents the electric double layer interaction energy in Eq. (10). The parameters in Eq. (11) are defined as follows: A is the Hamaker constant for the NP dispersion system, whose value is dependent on the types of NPs and the aqueous media; a is the radius of NPs; d is the separation distance between NPs. As for the parameters in Eq. (12), is the dielectric constant of aqueous phase; is the dielectric constant of vacuum; k is the Boltzman constant; T is the absolute temperature; is the electron charge; z is the charge number; is the surface potential of NPs (assumed to be equall to ζ-potential); is Debye length (Eq. 13):

| (13) |

where is the Avogadro constant, I is the ionic strength of the aqueous phase.

As shown in Eq. (12), an elevation in absolute value of ζ-potential () will lead to enhanced repulsive energy () and total interaction energy (), making it more difficult for NPs to form aggregates. Conversely, a reduction in favors the aggregation process.

The DLVO theory is crucial for the comprehension of the environmental factors that affect the aggregation process. Experimental results have confirmed that this theory is suitable for NP dispersion systems. Various environmental factors including pH, ion strength, natural minerals and organic matter play vital roles in NP aggregation. Liu et al. (2019a) and Mao et al. (2020) observed that the negatively charged surfaces of polystyrene NPs possessed more negative ζ-potentials with the increase of solution pH. This resulted in an elevation in , making NPs more stable according to DLVO theory. However, if the surface of NPs were positively charged at low pH conditions, an increase in solution pH may result in the aggregation due to a decrease in value (Ramirez et al., 2019). Inorganic ions also affect the aggregation process through changing the ionic strength of the solution. Higher concentrations of inorganic ions result in reduced , favoring the aggregation of NPs (Wu et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2019; Cai et al., 2018). Natural minerals such as clay tends to form heteroaggregates with NPs due to electrostatic interactions (Singh et al., 2019). Natural organic matter protects NPs from aggregation by elevating the value (due to the formation of eco-corona) (Ramirez et al., 2019; Saavedra et al., 2019). However, Yu et al. (2019) suggested that if the concentration of organic matter is high enough (to enable the existence of un-adsorbed free organic matters in the system), the co-existence of natural organic matter and inorganic ions may lead to the “bridging effect”. Inorganic metal cations (e.g., Ca2+) could bridge oxygen-containing groups of both NPs and the organic matter, resulting in heteroaggregation.

The conventional DLVO theory can be adapted to describe NP interactions in more complicated systems (e.g., soil). Liu et al. (2019c) adopted an extended DLVO theory to assess the interaction energy of NPs in porous media. Total NPs-soil interaction energy takes three forces into account: Van der Waals force, electrostatic double layer force, and the hydrophobic effect (described by the Lewis acid-base interaction). According to the theoretical calculations, aged NPs are likely to possess higher primary energy barrier, making them less likely to form aggregates. The theoretical calculation aligned with the experimental findings, that aged NPs have higher mobility in saturated porous media. Mao et al. (2020) assessed the aggregation behavior of NPs in the presence of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) produced by microorganisms during biofilm formation on NPs. To better understand the role of EPS in the aqueous media, steric repulsion was incorporated in conventional DLVO theory. The energy barrier was higher in solutions with EPS, which was consistent with the finding that EPS inhibited the aggregation of NPs through steric effects.

Understanding the aggregation behavior of NPs is critical for the assessment of environmental fate of NPs. However, current studies mainly focus on the spherical synthetic NPs, rather than naturally aged NPs with diverse shapes. The conventional DLVO theory is based on the “spherical” assumption, so modifications must be made when it comes to non-sphere nanoplastic particles.

4. Toxic effects on organisms

4.1. Toxic effects of NPs

4.1.1. Organisms in terrestrial ecosystems

Evidence has shown that NPs affect the soil microbiome. The activities of enzymes involved in C, N and P cycles (i.e., leucine-aminopeptidase, alkaline phosphatase,β-glucosidase and cellobiohydrolase) can be suppressed after polystyrene NPs addition (0.1–1 mg/kg) (Awet et al., 2018). Zhu et al. (2018) also observed a decrease in activities of key biomes dominating the nitrogen cycling. After feeding the soil oligochaete Enchytraeus crypticus with polystyrene NPs-added oatmeal (10 wt. %), relative abundance of Xanthobacteraceae, Isosphaeraceae and Rhizobiaceae in gut decreased significantly. Kim et al. (2020) observed the toxic effect of polystyrene NPs (530 nm) on nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. The number of offsprings decreased significantly (p < 0.05) when the NPs concentration reached 10 mg/kg. However, most of these studies have neglected the effects of soil properties on NP toxicity. Adsorption of NPs by soil organic matter, the oxidation of NPs induced by organic acids (e.g., root exudates), and the interactions with soil minerals may affect the bioavailability and toxicity of NPs.

Apart from the toxicity to microorganisms, NPs can also affect plant growth. NPs can be taken up and sequestered by root (Fig. 3 b, c, d), and even translocated to aboveground tissues (Fig. 3a). Larger NPs can be accumulated in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3c), while smaller ones (∼ 30 nm) may even enter the nucleus (Fig. 3d), interfering with chromatin structure and function. In this way NPs may induce genotoxic effects (cytogenetic anomalies and micronuclei) (Giorgetti et al., 2020). The internalization of NPs in various cellular compartments resulted in reduced root growth of onion (Giorgetti et al., 2020). Interestingly, internalization of NPs may also have positive effects on plant growth. After exposure to polystyrene NPs (0.01–10 mg/L), root elongation of Triticum aestivum L. (wheat) was significantly (p < 0.01) enhanced by 89 %–123 %, as compared with the control (Lian et al., 2020). Besides, increases in plant biomass, carbon and nitrogen contents were observed. NPs exposure resulted in enhanced growth of wheat seedlings without any overt stress. This was probably because polystyrene NPs increased the activity of α-amylase as a nanocatalyst, thus accelerating the production of soluble sugars from the starch granules (Lian et al., 2020). However, NPs were also found to accumulate in wheat tissues (Fig. 3a, b), indicating a potential threat to higher trophic levels along the food chain. The contradictory effects of NPs on plants as observed by current studies may stem either from the soil properties or the plant characteristics, and deserves further investigations.

Fig. 3.

Accumulation of polystyrene NPs in plant tissues: (a) wheat leaves after 10 mg/L NPs treatment (Lian et al., 2020); (b) wheat roots after 10 mg/L NPs treatment (Lian et al., 2020); (c) onion root cell after 100 mg/L NPs treatment, NPs were observed in the cytoplasm. M, mitochondria; N, nucleus (Giorgetti et al., 2020); (d) onion root cell after 1000 mg/L NPs treatment, NPs were observed in the nucleus. CR, chromatin (Giorgetti et al., 2020). All images are reproduced with permission.

4.1.2. Organisms in aquatic ecosystems

Ecotoxicity of MPs and NPs in the marine environment have been extensively investigated and reviewed (Barría et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2020; Ganesh Kumar et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2019a). NPs can affect organisms from various trophic levels, including bacteria (Sun et al., 2018a), algae (Bhargava et al., 2018), arthropods (Zhang et al., 2020b), echinoderms (Della Torre et al., 2014), bivalves (Baudrimont et al., 2019), rotifers (Manfra et al., 2017) and fish (Brun et al., 2019). Bioaccumulation of NPs in tissues (Pitt et al., 2018), effects of NPs on growth and reproduction (Liu et al., 2020), NP-induced damages to immune system (Bergami et al., 2019), neurotoxicity (Sökmen et al., 2020) and alterations on metabolism pathways (especially the lipid metabolism) (Brandts et al., 2018) are several major concerns in this field. A comprehensive review and detailed discussion on the toxic effects of NPs on marine organisms is provided elsewhere (Barría et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2020).

Current research regarding NPs in aquatic ecosystems mainly focuses on marine ecosystems. However, freshwater ecosystems are able to transport and accumulate large quantities of NPs as well. Several studies have investigated the toxic effects of NPs on freshwater aquatic organisms. Cui et al. (2017) observed that polystyrene NPs (52 nm, 5 mg/L) caused abnormal embryonic development and inhibited reproduction of Daphnia galeata, a freshwater crustacean. van Weert et al. (2019) examined the effects of polystyrene NPs (50–190 nm, up to 3 wt. % addition in the sediment, 21 days) on the growth of macrophytes Myriophyllum spicatum and Elodea sp.. A significant increase in root biomass was observed (p < 0.05 for both plants), but the reason for this phenomenon remains unclear. It is hypothesized that sorption of NPs onto root surface hampered the uptake of nutrients. To overcome this stress, the macrophytes increased the root biomass by increasing the root length, root diameter and the number of roots for the better uptake and transport of essential nutrients. Apart from potential physical blockage caused by adsorption, NPs can also affect the reproduction of aquatic plants. Exposure to polystyrene NPs (98 nm, 0–100 mg/L in artificial freshwater, 9 days) resulted in sex differentiation in gametophytes of an endangered fern, Ceratopteris pteridoides (Yuan et al., 2019). Due to environmental stress induced by NPs, an increase in male gametophytes were observed, which will cause drastic consequences for the reproductive success.

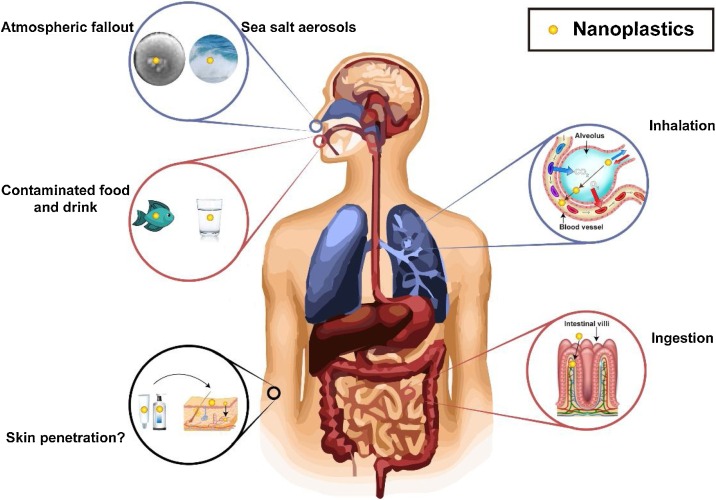

4.1.3. Human beings

Inhalation, dermal exposure and ingestion are potential exposure pathways of NPs (Fig. 4 ). Inhalation of NP-containing aerosols and the penetration of NPs into the capillary blood system enable this nano-sized contaminant to distribute throughout the human body (Lim et al., 2019). Evidence has shown that atmospheric fallout is a potential source of MPs and NPs (Prata, 2018), but there is no available data concerning the concentration of airborne NPs. (Wright and Kelly (2017)) suggested that sea salt aerosols, wind-driven transport of NPs from sludge fertilizers, release of NPs from clothes, and the degradation of agricultural PE sheets are potential sources of NPs in the air. Particle size and concentrations determine the toxicity of airborne NPs, and more studies should examine the potential health risks associated with inhalation of NPs.

Fig. 4.

Human exposure pathways of NPs. Blue – inhalation; red – ingestion; black – dermal.

The potential contact of NPs with human skin occurs through the exposure to contaminated air or water, or the use of personal care products. There is some doubt whether NPs can penetrate the human skin. Stratum corneum acts as a physical barrier of the skin. Besides, the hydrophobic characteristic makes it hard for NPs to penetrate through skin in water (Lehner et al., 2019). Campbell et al. (2012) found that polystyrene NPs with diameters ranging from 20 to 200 nm could only penetrate to a depth of 2–3 μm of the stratum corneum. However, exploitation of ingredients in personal care products may favor the penetration of NPs. Extrapolation of results from other nanoparticles may provide fresh insights into this topic. Evidence has shown that ingredients in skin care lotions (i.e., glycerol, urea and alpha hydroxyl acids) enhance the penetration of quantum dot nanoparticles (20.9 nm) into excised human skin (Jatana et al., 2016). Although the surface chemistry of nanoplastics and other nanoparticles (e.g., quantum dot, metal oxide nanoparticles) may be different, the penetration of NPs is highly dependent on the particle size, so the results from nanoparticles may provide useful information on the penetration of NPs with similar sizes. In general, skin penetration may contribute to the human intake of NPs, but more direct evidences are needed.

Ingestion of contaminated food and water is probably the major exposure pathway of NPs. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with a large surface area of approximately 32 m2 (Helander and Fändriks, 2014), is the primary site for the uptake of NPs (Fig. 4). NPs may cross intestinal villi and enter the blood vessel, and the formation of protein-plastic complex (so-called protein corona) is confirmed by in vitro studies (Gopinath et al., 2019). This phenomenon is critical to the toxicity of NPs in organisms, since the interactions between tissues and organs occur with protein-coated, rather than bare NPs (Lehner et al., 2019). Results from an in vitro study of human blood cells indicate that protein-coated NPs can cause higher cytotoxic and genotoxic effect compared with virgin NPs (Gopinath et al., 2019). This is probably because the formation of biomolecular corona on the surface of NPs helps them escape from the immune system, resulting in prolonged existence in the circulation system. The binding mechanism of protein corona with NP is not well understood, but it is believed that non-specific physical attraction (i.e., Van der Waals force), hydrogen bond, and delocalized π bond contribute to the formation of this protein-plastic complex (Gopinath et al., 2019; Treuel et al., 2014).

A limited number of rodent in vivo and human in vitro studies have shown that NPs can have adverse effects on the immune system. Toxic effects of NPs on human cells include induced up-regulation of cytokines involved in gastric pathologies (Forte et al., 2016), disruption of iron transport (Mahler et al., 2012), induction of apoptosis (Inkielewicz-Stepniak et al., 2018), endoplasmic reticulum stress (Chiu et al., 2015) and oxidative stress (Ruenraroengsak and Tetley, 2015). One feasible way for the better understanding of NPs’ toxicology is the extrapolations from nanoparticles. However, Bouwmeester et al. (2015) suggested that the extrapolation of information on nanoparticles to nanoplastics should be conducted with care, since NPs possess evidently different surface chemistry. For further information regarding the toxicology and the feasibility of extrapolation, we refer readers to Lehner et al. (2019) and Bouwmeester et al. (2015).

4.2. Toxic effects of pollutants retained onto NPs

Due to the large specific surface area of NPs, various contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and heavy metals can be sorbed on their surfaces (Bradney et al., 2019). The ability of contaminant sorption on NPs can be described using a sorption coefficient (Endo and Koelmans, 2019) (Eq. 14):

| (14) |

where is the sorption coefficient, and refer to the concentrations of contaminants in plastic and aqueous media, respectively (at equilibrium). The sorption coefficient is crucial for the understanding of sorption and desorption behaviors of contaminants. If the actual Cp/Cw ratio is below Kpw, adsorption occurs. If the Cp/Cw ratio is above Kpw, desorption takes place. If the Cp/Cw ratio falls equal to Kpw, the adsorption-desorption system reaches equilibrium. Equilibrium can occur in natural conditions (Endo and Koelmans, 2019). For instance, in marine ecosystems, sorption of contaminants to floating NPs may proceed till equilibrium, since the contaminant concentration is relatively stable over time. However, in a wastewater treatment facility, sorption equilibrium is less likely to occur, since contaminant concentrations fluctuate with time.

Understanding the sorption behavior of NPs is quite crucial in assessing the toxicity of various contaminants. Organisms accumulate contaminants via various pathways (Fig. 5 ), including the direct uptake of free available contaminants and the uptake of NP-adsorbed contaminants. It is noteworthy that contaminants can either desorb from or still attach to NPs after bioaccumulation (Jiang et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2017). Results from toxicological research on MPs (Alimi et al., 2018; Ding et al., 2020) and nanoparticles (Deng et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017a) can be extrapolated to propose several potential mechanisms. Firstly, higher specific surface areas of aged NPs favor the contaminant adsorption, which may decrease the biological uptake of desorbed contaminants. Secondly, the increase in polarity of NPs (e.g., introduction of carbonyl groups) during photo-oxidation may elevate the risks of NP-associated non-polar organic contaminants, while decreasing the risks of heavy metals (as a result of enhanced surface complexation). Furthermore, the hydrophobicity of contaminant itself affects the toxicity, since hydrophilic contaminants are more likely to be desorbed from NPs after uptake. As has been discussed above, the sorption coefficient plays a vital role in adsorption-desorption of nanoparticles. However, this parameter is often neglected. Before investigations on the toxicity of attached contaminants, it is necessary to conduct sorption experiments to further examine in which form contaminants are accumulated.

Fig. 5.

Factors determining the toxicity of contaminants attached onto NPs. Organisms may either uptake free-available contaminants directly, or uptake NP-adsorbed contaminants. The sorption coefficient, , is critical for the understanding of adsorption-desorption. The toxicity of NP-attached contaminants are mainly affected by the size and concentration of NPs, whilst the toxicity is also dependent on the species and the contaminant hydrophobicity/polarity.

4.2.1. Organic contaminants

Discrepancy exists whether NPs can make organic contaminants more toxic (Table 3 ). Several studies have found that toxicity can be greatly enhanced due to the high adsorption capacity towards hydrophobic organic contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) (Jiang et al., 2018) and bisphenol A (Chen et al., 2017). Enhanced adsorption may result in enhanced bioaccumulation. For instance, Chen et al. (2017) found that polystyrene NPs enhanced the bioaccumulation of bisphenol A in head and viscera of zebrafish, which may stem from the enhanced uptake of NP-adsorbed form. Ma et al. (2016) observed that phenanthrene and polystyrene NPs revealed an additive toxic effect on Daphnia magna. However, other studies have observed a reverse trend, that enhanced adsorption resulted in reduced toxicity. Trevisan et al. (2019) noticed that a decrease in PAHs bioaccumulation with the presence of NPs resulted in reduced toxicity to zebrafish. Zhang, Qu, Lu, Ke, Zhu, Zhang, Zhang, Du, Pan, Sun and Qian (Zhang et al., 2018) observed that amino-modified polystyrene nanoparticles could alleviate the toxic effect of glyphosate on Microcystis aeruginosa through adsorption.

Table 3.

Toxicology of organic contaminants attached to NPs.

| Contaminant | NP type | NP size (nm) | NP concentration (mg/L) | Organism | Toxic effects | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisphenol A | Polystyrene | 50 | 1 | Zebrafish | Neurotoxicity | Enhance the accumulation of Bisphenol A in head and viscera by 2.2, 2.6 folds, respectively | (Chen et al., 2017) |

| 2,2′,4,4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether and triclosan | Polystyrene | 50 | 10 | Marine rotifer Brachionus koreanus | Generate oxidative stress | Inhibit the membrane defense of organic contaminants (inhibit the activities of multidrug resistance proteins and P-glycoproteins) | (Jeong et al., 2018) |

| Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | Polystyrene | 100 | 2, 5, 10, 20 | Daphnia magna | Lethal | Enhance the accumulation of PCBs by 1.4–2.6 folds | (Jiang et al., 2018) |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Polystyrene | 568 | 0.4 | Clamworm Perinereis aibuhitensis | Lethal | NPs at environment relevant concentrations (0.4 mg/L) contributed little to bioaccumulation of PAHs | (Jiang et al., 2019) |

| Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | Polystyrene | 100 | 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 75 | Daphnia magna | Lethal | Low NP concentration (1 mg/L) decreased the lethality, while high NP concentration (75 mg/L) increased the lethality | (Lin et al., 2019) |

| Tetracycline | Polystyrene | 50 – 100 | 1000 mg/kg | Enchytraeus crypticus* | Not investigated | The number of antibiotics resistance genes increased | (Ma et al., 2020b) |

| Phenanthrene | Polystyrene | 50 | 2.5, 5, 8.5, 11, 14.5 | Daphnia magna | Physical damage, lethal | The toxicity of NP and phenanthrene showed an additive effect | (Ma et al., 2016) |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Polystyrene | 45 | 10 | Zebrafish | Impair mitochondrial energy production | NP decreased the toxicity of PAHs but impared mitochondrial energy production | (Trevisan et al., 2019) |

| Glyphosate | Amino-modified polystyrene | 200 | 3, 5, 10, 20 | Microcystis aeruginosa | Inhibit photosynthetic capacity | NP has a strong adsorption capacity for glyphosate, alleviating the toxic effect of glyphosate | (Zhang et al., 2018) |

Note: *Organisms in terrestrial ecosystems.

Several reasons may account for this discrepancy (Fig. 5). Concentration of NPs affects the sorption process greatly. For instance, when NP concentration is very low (i.e., 0.4 mg/L), NP-adsorbed pyrene accounted for less than 1% of the total pyrene bioaccumulation in Perinereis aibuhitensis (Jiang et al., 2019). Pyrene is mostly free available in this case, so NPs had little effect on its toxicity. Besides, the particle size of NPs affects the number of available sorption sites, thus affecting the sorption coefficient. For instance, Velzeboer et al. (2014) found that NPs enhanced PCBs sorption by 1–2 orders of magnitude as compared with MPs. In addition, toxicity of certain contaminants is species-dependent (Halm-Lemeille et al., 2014; Luzardo et al., 2014), so the selection of different species may result in varied results. Variance in hydrophobicity/polarity of organic contaminants also results in different sorption capacities. Hydrophobic organic contaminants tend to adsorb onto NPs (Kpw > 1), indicating that an enrichment in plastic phase rather than aqueous phase will occur. Polarity affects the adsorption mechanisms. Polar compounds bind with NPs through surface adsorption, while non-polar/weakly polar compounds tend to adsorb in the inner matrices of NPs (physical entrapment) (Liu et al., 2018). This may lead to the variance in bioavailability and mobility.

As shown in Table 3, most of the studies used organisms living in aquatic ecosystems (e.g., zebrafish, Daphnia magna, clamworm). To date, the toxic effects of NP-attached contaminants on terrestrial ecosystems have not been fully investigated. Limited evidence have shown that NP-attached contaminants affects soil microbiome (Ma et al., 2020b). Several other challenges and future directions in this field are discussed in section 6.

4.2.2. Heavy metals

Unlike organic contaminants, heavy metals cannot be degraded, rendering wide distribution due to both natural and anthropogenic sources (O’Connor et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2020). Bioaccumulation of toxic metals along the food chain poses a severe threat to human health (Butt et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a, 2019). However, the toxicity of NP-adsorbed heavy metals is poorly investigated. As has been discussed above, explorations in adsorption behavior of NPs provides useful information on the potential risks of bioaccumulation. Davranche et al. (2019) examined the metal binding ability of NPs. NPs (hydrodynamic diameter 150–450 nm) were produced by the sonication of MPs (collected on the beach), and Pb(II) was selected as the target contaminant. Pb(II) sorption fitted the pseudo-second order kinetic model, indicating that chemical reactions rather than intraparticle diffusion were the rate-limiting step. NPs were proven to be strong adsorbents, with similar Freundlich adsorption constant compared to Fe oxyhydroxides. It is suggested that more studies should be conducted to further assess the toxic effects of NP-adsorbed metals on organisms.

Pristine particulate plastics with high hydrophobicity have a lower likelihood of interacting with heavy metals when compared to particulate plastic-DOM assemblages. In the latter case, there is greater interaction and increased retention of trace elements. For example, Wijesekara et al. (2018) identified the adsorption of heavy metals (i.e., Cu) onto particulate plastics that had modified surfaces due to DOM adsorption. The findings implied that modified particulate plastics adsorbed significantly greater concentrations of Cu than pristine particulate plastics, possibly due to the introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups (enhance surface complexation). Furthermore, long term pre-modification (e.g., photooxidation and attrition of charged materials) that contributes to aging of plastics causes these aged particles to have a great metal sorption capacity.

4.2.3. Potential carrier of pathogens

Previous studies indicate that many bacteria can attach/grow on various plastics surface in either aquatic environment or ambient conditions. The concept of “plastisphere” was proposed based on observation that plastics function as habitats and are rapidly colonized by marine microorganisms (Amaral-Zettler et al., 2020; Zettler et al., 2013; Kirstein et al., 2019). The plastisphere is the layer of microbial life that forms around every piece of floating plastic. Plastics may not only serve as a novel microhabitat for biofilm colonization, but also increase the likelihood of pathogens propagating. Evidence has shown that floating plastics in aquatic ecosystems can act as vectors (a means of transport) for pathogens such as Vibrio (Zettler et al., 2013) and Pseudomonas (Wu et al., 2019). A study by Huang et al. (2019) even observed the enrichment of potential human pathogens Nocardiaceae, Campylobacteraceae and Vibrio in soil as a result of LDPE film application. Apart from the selective enrichment of pathogens, the abundance of antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) may also increase within the plastisphere. Wu et al. (2019) found that the ARG abundance of the plastic biofilm was 3-fold higher than that of the river water samples, indicating the enrichment of ARGs by the plastisphere. Wang et al. (2020b) noticed that the adsorption of antibiotics lead to a significant shift in ARGs (i.e., sul1, tetX and ermE) on PE plastics. In addition, plastics in the soil may also increase the abundance and act as a sink of ARGs, affecting soil health in the long term (Lu et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2018b).

Recently, a study on COVID-19 on contaminated surfaces and in aerosols suggests that people may acquire the coronavirus through the air and after touching contaminated objects. The virus was detectable for up to three hours in aerosols, up to four hours on copper, up to 24 h on cardboard and up to two to three days on plastic and stainless steel (van Doremalen et al., 2020). This has raised a question about potential risk of air-borne disease by coronavirus and flu virus via plastic MPs and NPs in polluted air.

5. Risk assessment and mitigation

5.1. Nanoplastics, ecosystems and human society - a DPSIR framework

It does take scientists decades to develop the concept of NPs inevitably, because there’s adequate evidence indicating that plastic substances do break into NPs and remain well detectable all around the environment (Waring et al., 2018), and reluctantly, because their more widespread distribution and harder isolation methods compared with MPs (Hernandez et al., 2017; Revel et al., 2018) will have led to somehow severer threats on living creatures, human society and even the whole ecosystem. To better understand the risk associated with NPs, a DPSIR (driving forces – pressures – states – impacts – responses) framework can be adopted (Fig. 6 ). Due to the increase in population and economic growth, global demand of plastic products keeps growing, leading to greater plastic waste generation (driving forces). This has led to the release of MPs and NPs from various land-based or sea-based sources of plastic waste input (pressures) (section 3.1). After entering the environment, NPs undergo aging, aggregation and migration processes. For terrestrial ecosystems, soil act as a major sink of NPs, whilst a number of plastic particles will enter the aquatic systems and end up in river or lake sediments, or in the ocean (state). The presence of NPs in the environment may pose risks to both terrestrial (section 4.1.1) and aquatic organisms (section 4.1.2). NPs may also threat the human health through the food chain, or through direct inhalation and dermal exposure (section 4.1.3) (impacts). It is therefore necessary to seek for risk mitigation strategies in response to NP contamination (responses), which will be discussed in the following section.

Fig. 6.

A DPSIR framework for the risk assessment of NPs. The growing demand of plastic products as a result of the increase in population and economic growth is the driving force. This has led to the release of MPs and NPs from various land-based or sea-based sources of plastic waste input (pressures). After entering the environment, NPs undergo aging, aggregation and migration processes. NPs in the terrestrial ecosystems may end up in soils, and some of them will be bioaccumulated by plants or migrate to the groundwater. A number of plastic particles will enter the aquatic systems and end up in river or lake sediments, or in the ocean (states). The presence of NPs in the environment may pose risks to both terrestrial and aquatic organisms. NPs may also threat the human health through the food chain, or via direct inhalation and dermal exposure (impacts). It is therefore necessary to seek for risk mitigation strategies in response to NP contamination, including the development of novel remediation strategies, the establishment of policies, and the enhancement of environmental education (responses).

5.2. Risk mitigation strategies

Due to the substantial gap of knowledge regarding NPs (e.g., their amount in the environment, environmental behaviors, exposure pathways), challenges remain in the risk assessment of NPs. To better understand the risks associated with NPs, substantial scientific efforts are imminent. The first step, however, is the acquisition of robust data on exposure in marine, freshwater and terrestrial settings (Wagner and Reemtsma, 2019). Currently they are very limited due to the lack of precise analytical approaches (section 2.1), so the environmental concentrations of NPs are only estimates (Schwaferts et al., 2019; Wagner and Reemtsma, 2019). For further information regarding the risk assessment of NPs, readers are referred to Alexy et al. (2020) and Pinto da Costa et al. (2019), who have provided comprehensive overviews on this topic.

Solutions to NP pollution basically lie in the following aspects: 1) development of novel remediation technologies, 2) policy making and 3) public awareness (Fig. 7 ). Although little effort has been made regarding the remediation strategies of NPs, several possible directions have been proposed by present studies. Biotechnology advances make it possible to gradually replace conventional non-biodegradable plastic products by biodegradable ones (Silva et al., 2018), while special enzymes, bacteria and fungi that are capable of degrading plastics can be introduced to promote the disposal process (Pico et al., 2019). The biodegradation process can be divided into three stages (Tosin et al., 2019; Lucas et al., 2008):

Fig. 7.

Technical, legal and social strategies for the remediation and risk containment of NP contamination.

Stage 1: depolymerization of plastics into monomers or oligomers. This process, which is induced by extracellular enzymes, takes place outside the microorganisms.

Stage 2: assimilation of monomers and oligomers. The depolymerized products enter the cell, and become part of the living biomass of microorganisms through metabolism.

Stage 3: mineralization. The assimilated plastic metabolites will be oxidized, forming CO2 and H2O.

To prevent NP from entering the aquatic ecosystems, the most effective engineering technology is to remove NPs in a wastewater treatment facility. Pre-treatment strategies including density separation and coagulation as well as membrane separation have proven effective for the removal of MPs in drinking water, but their ability to remove NPs should be further examined (Enfrin et al., 2019). As has been discussed in section 3.3, aggregation and settlement is an important phenomenon determining the environmental fate of NPs. Future studies may rely on the pH control, and the addition of inorganic or organic matters to enhance the aggregation of NPs in a wastewater treatment process, leading to effective removal of NP. Very limited research examined the risk mitigation strategies of NPs in terrestrial ecosystems. Available literature suggests that addition of soil amendments (e.g., biochar) could reduce the migration of NPs in porous media, thus mitigating the risks through retention/stabilization (Tong et al., 2020a). It is herein proposed that remediation strategies towards other contaminants can be further extrapolated to NPs. For instance, addition of “green” remediation materials, such as engineered biochar (Wang et al., 2020c; Rajapaksha et al., 2016) and clay minerals (Simoes et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2017b), have proven effective for the immobilization organic contaminants in soil. Considering the organic polymeric nature of NPs, the mechanisms involved in organic contaminant immobilization and NPs retention may be quite similar (e.g., π-π interactions, hydrogen bonding). Therefore, successful attempts in organic contaminant stabilization may shed light on the remediation of NPs in terrestrial systems (especially the soil).

Policy making is the most efficient and reliable way to keep NPs-related risks under control, yet one should always keep in mind that a policy can only be promulgated after its effects have been carefully assessed (da Costa, 2018). In practice, evidence-based policies are able to tackle the problems caused by NPs in the whole life cycle, such as the US Microbead-Free Waters Act (acting on the source) (the 114th United States Congress, 2015), the Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive (94/62/EC) (acting on the using stage) (European Commission, 1994), and the Directive on the Landfill of Waste (1999/31/EC) (acting on the disposal stage) (European Commission, 1999). Regarding the fact that attention to emerging contaminants by policy makers often peak a few years later than scientific attention (Halden, 2015), more interactions between policy makers and researchers are encouraged to bring useful findings into practice as soon as possible.

Since plastic products are an essential part in daily life, raising public awareness of the NPs could be a feasible and advantageous solution to manage the potential risks of NPs. As could be expected, this particular aspect is fundamental but inefficient, as it usually takes months or years to alter people’s thoughts and attitudes, not to mention that such process ought to be supported by concrete scientific evidence (van der Linden et al., 2015).

6. Final considerations

6.1. From the ocean to the total environment

Although research on marine plastics remains at the forefront, researchers have begun to address the concern of NPs in other ecosystems. The largest gap in current research is the understanding of the environmental behavior and ecologic impacts of NPs in terrestrial systems. Due to the lack of available information regarding the concentrations, migration characteristics, bioaccumulation risks and toxic effects of NP particles, it is hard to assess whether these tiny particles will affect the well-being of terrestrial ecosystems. As discussed in section 3.2, migration of NPs in porous media (e.g., soil, sediment and sand) have been investigated by recent studies. However, it is argued that most of these studies have neglected the role of natural forces (such as rainfall, freeze-thaw, etc.) on NP migration, with only one exception that considered the rainfall process (Keller et al., 2020). Besides, NPs may even enter the groundwater through vertical colloidal migration, which has been neglected by most studies (O’Connor et al., 2019). Although several attempts have been made to explore the bioaccumulation of polystyrene NPs by microorganisms and plants, controversy still exists whether NP particles can induce toxic effects on organisms living in terrestrial systems. Some studies even observed that the presence of NPs can enhance the plant growth, but the mechanisms involved in this process remain unknown (Lian et al., 2020). Future explorations on the effects of NPs on the agroecosystem should be given higher priority, since it is very likely that soil may act as a long-term sink for NPs and that NPs in crop tissues may be ingested, threatening the food safety in the long run (Ng et al., 2018; Rillig et al., 2017).

Although information from marine plastic studies can be extrapolated to freshwater to some extent, researchers should bear in mind that NPs in freshwater will cause threats to the environment in their unique ways. For instance, apart from toxic effects on microorganisms and fish, NPs may affect the growth and reproduction of aquatic plant species as well (Yuan et al., 2019). In freshwater systems, a shift in ionic strength and dissolved organic matter content will result in distinct aggregation behaviors of NPs, which may affect the sedimentation process greatly. In addition, given the lack of terrestrial studies to date, current knowledge on the freshwater systems, especially the migration characteristics of NPs in the sediment and the phytotoxicity of NPs, may be helpful to infer the environmental behavior and toxicology of NPs in the terrestrial ecosystems.

It is widely acknowledged that NPs are widely spread in the hydrosphere, but research on the presence, transport and toxicity of NPs in the atmosphere are scarce. Evidence is mounting that inhalation of airborne particles containing NPs can induce toxic effects on human lung cells (Lim et al., 2019; Lehner et al., 2019; Paget et al., 2015; Deville et al., 2015), but the origins and the concentrations of NPs in the air remain unknown. MPs have been detected in the atmosphere of urban (Dris et al., 2015; Klein and Fischer, 2019) and even remote mountain areas as a result of long-range transport (Allen et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019b). Moreover, airborne plastic particles will enter terrestrial and aquatic systems through deposition (Mbachu et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020c). The atmosphere may also serve as a “superhighway” for NPs. Future research on the airborne NPs is desperately needed.

6.2. From polystyrene to other plastic types

According to the literature reviewed, the most frequently used nanoplastic particle is the polystyrene (PS). However, this is not consistent with the global plastic demand. It is estimated that the polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) hold significantly higher proportion of annual plastic production (29.7 %, 19.3 % and 10 %, respectively) as compared with polystyrene (PS), which only accounts for 6% (PlasticsEurope, 2019). Considering the fact that various types of NPs possess distinct physicochemical properties (i.e., functional groups, polarity, hydrophobicity, etc.), it is doubtful whether these studies can reveal the environmental fate and toxicology of nanoplastics from a wide range of polymers used for plastic manufacture. For instance, plastic mulching is a widely-adopted technique to promote agricultural production in many countries (Ng et al., 2018; Qi et al., 2020). It is estimated that plastic mulch film covers over 20 million hectares of farmland in China, which is a dominant source of NPs in the agroecosystem (Liu et al., 2014). However, plastic mulch films are mainly made of PE rather than PS. When it comes to the migration and bioaccumulation characteristics of plastic particles in the farmland soil, extrapolating the results from PS NPs is somehow inappropriate, and can be misleading to some extent. Besides, PE mulch films usually contain considerable amounts of phthalate esters (PAEs) that can be released into soil. Current studies have failed to assess the toxic effects of these additives.

6.3. From synthetic to naturally weathered NPs